X. THE GREAT LEAP FORWARD

X. THE GREAT LEAP FORWARD

The economist Alexander Field has recently made the striking claim that it “was not principally the Second World War that laid the foundation for postwar prosperity. It was technological progress across a broad frontier of the American economy during the 1930s.”93 Yes, the years 1929–1933 saw a crash in effective demand, the collapse of heavy manufacturing, and a devastating hollowing out of labor markets. Simultaneously with those disasters, however, the working economy was turning in one of the best records in total factor productivity (TFP) in the country’s history—even better than the spectacular growth record in the 1920s. The concept of TFP sprang from the 1950’s research of two well-known “growth economists,” Moses Abramovitz and Robert Solow, who reconstructed economic databases for the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They found they could explain most nineteenth-century growth by summing the contributions of changes in the inputs of labor and capital (e.g., new plants and machinery). In the first quarter of the twentieth century, however, growth was consistently higher than suggested by the identifiable inputs. Solow called the unexplained growth factors the “residual.” TFP, then, was revised to include inputs of labor and capital plus the residual, which was assumed to capture the invisible technology-enabled improvements in the use of the inputs. That residual began to shrink in the second half of the twentieth century, and is now nearly undetectable, which is raising some alarm among policy experts.94

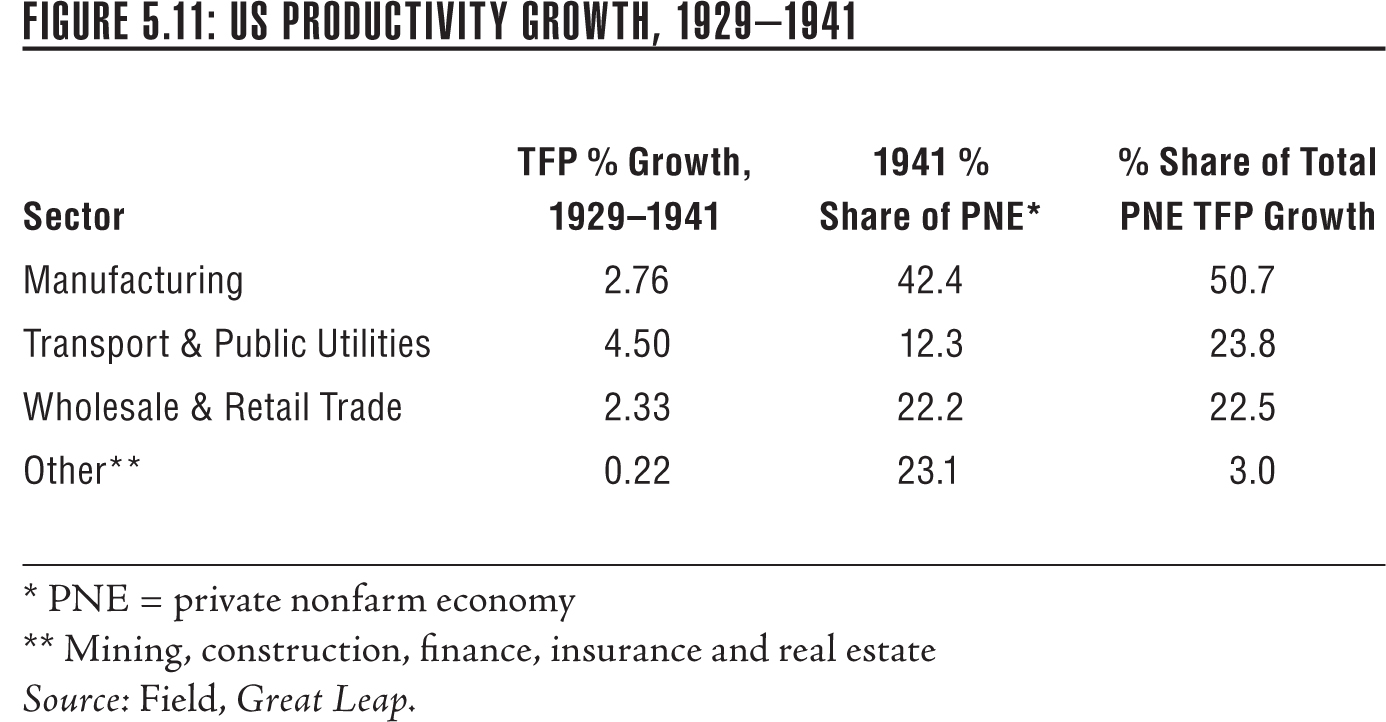

The twenties was an extraordinarily productive decade, but its advances were almost entirely explained by the growth in manufacturing TFP—an amazing 5.12 percent a year from 1919–1929. In the thirties, with much of the factory productivity revolution already in the bank, manufacturing TFP dropped to 2.76 percent—which is still a very strong number. Capital investment played only a minor role in the thirties, and the TFP gains came from two broad categories of progress. First, as we have seen in the automobile industry, smaller, older plants were forced to close, raising the average productivity of them all, and second, manufacturers raised their scientific game. Despite the black clouds that still hung over the entire economy, industry made major investments in research and scientific manpower in the thirties. Total research and development employees in American manufacturing rose from 6,250 in 1927, to 11,000 in 1933, to 27,800 by 1940. Specific advances in manufacturing technology during the decade included improving the thermal efficiency of engines; reusing waste gases and other detritus; development of plastics, tungsten, and carbon alloys; and a host of other individually modest research-based advances.95

With manufacturing productivity merely very good in the 1930s, other sectors had to jump ahead to make up the shortfall.

The “private nonfarm economy” excludes the government and farm sectors, since they do not lend themselves to TFP measurement.* About a third of the spectacular TFP gains in transport and utilities were concentrated in trucking and warehousing. The wildfire growth of the automobile industry in the 1920s pointed ineluctably toward a colossal national traffic jam, until infrastructure investment, much of it financed by the government, built out a national highway bridge and tunnel system. That connecting system of highways enabled the first modern trucking industry, the consummate tool to speed deliveries to the world’s first nation of consumers. The second-best sector contribution to transport and utilities TFP was the railroads, as their integration with short-haul trucking vendors created what must have been the most flexible haulage industry in the world. The final major contributor in the transport and utility sector was the electric power industry as it continued to ride up the golden ladder of scale efficiencies, filling in the blank spots in their local service areas and prospering from the ubiquitous and thickening web of consumer electrical necessities. The final sector to show rapid TFP growth was wholesale and retail distribution, a natural twin of transport and utilities. Note that its 2.33 percent is the lowest of the three most productive sectors, but since its share of the economy was almost twice as large as the transport and utility sector, the two sectors made very similar contributions to the economy’s dynamism.96

Field’s research casts a new light on the conventional story that World War II “ended the Depression.” For sure, the flood of war spending was a massive “demand shock” that quickly mopped up the Depression-era excess workers. But there is little evidence of a wartime “supply shock” that created the infrastructure to both win the war and power America’s postwar success. While the war accelerated some specific technologies—like airframes, antibiotics, and munitions—the disruptions caused by rapid-fire national mobilization and demobilization, along with other wartime distortions, probably outweighed the positive developments. The strong post-war economy, Field argues, was the legacy not of the war, but of the combination of high productivity gains in manufacturing—spectacular in the 1920s and still strong in the 1930s—plus the crucial 1930s capacity increases in industrial R&D, transportation, communications, public utilities, warehousing, and distribution, much of it financed with public funds. America’s world-class productive capacity was not, in the main, created in wartime; it was already there, awaiting conversion to new purposes.