18. Good-bye Messers

DURING the late winter of 1967 rumours began to reach Burgeo that Canada was celebrating her Centennial; the anniversary of the Act of Confederation which made a nation out of the northern British colonies of North America. Most residents of Burgeo found these rumours quite perplexing. As far as they were concerned. Confederation took place in 1949 when Canada was belatedly admitted into union with Newfoundland. As Uncle Dorman Collier, an elder of the village, explained to a group of men gathered in his fish store one afternoon: “A cen-teen-ial is supposed to be one hunnert year. 1949 to 1967 be more like sixteen year. Anyway ’tis nowhere nigh a hunnert. They fellows on the mainland must be some short on larnin’.”

Nobody got very excited about the Centennial, but it was different when Burgeo heard about Expo 67 which, if the reports were to be believed, was going to be the biggest blowout Canada had ever had. Everyone was going to be there. All the major nations were going to build pavilions. Countries like New England, Cuba, Texas, Quebec, and Mali were all going to have their own pavilions. It was these pavilions that caught the interest of the people of Burgeo.

No one knew what a pavilion was until Dorman took it on himself to find out. He looked it up in an ornate calf-bound dictionary that had been brought to Burgeo by Captain Elisha Fudge on his return from a voyage to Portugal with salt cod in 1867. Dorman had inherited this dictionary and he made good use of it, despite the fact that it was printed in Portuguese and Dorman did not know any Portuguese. The way he solved this problem was to make a list of all the words he wanted to look up and then wait for the arrival of a Portuguese dragger, two or three of which called at Burgeo every year for emergency supplies. When one arrived, Dorman would carry his list and dictionary on board and find a member of the crew who could translate for him.

The first Portuguese dragger of the year put in to Burgeo on May twenty-eighth. She was the Santa Jorge, fifteen weeks out of Lisbon, and about thirteen weeks out of alcoholic stimulants. When Dorman boarded her with his book and a bottle of contraband alky, he was royally received.

I met him a few days later at the Cottage Hospital. He said he had found out what a pavilion was, but he couldn’t tell me right then because he didn’t think it was “fitten” for the ears of the nurses. He said he would write it out for me and send it to Messers in a sealed envelope.

He was as good as his word.

Dear Skipper Mowat.

A pavilion is a sort of a tilt, like a tent only bigger. Mostly it is made of canvas and silk with pictures painted onto it. It was built by Kings mainly in lonely spots where nobody would know what was going on into it. I would not tell you what was going on into it but I guess you can guess Ha Ha Ha.

Yrs respectfully,

Dorman.

When this explanation of what a pavilion was percolated around the village it generated a mass movement to attend Expo. The two ministers were against it, and so was the majority of the women. Madge Kearley was in favour. Madge was what you might call a working spinstress. She had worked hard all her life and didn’t have much to show for it except thirteen children. Madge said that a bunch of kings would be a nice change from a bunch of Portuguese sailors who had been out from Lisbon fifteen weeks, Madge said she was going to go to Expo if she had to swim and if she missed any pavilions it wouldn’t be for want of trying.

The excitement about Expo had its unsettling effect upon almost everyone in Burgeo, and Claire and I and Albert were not immune. We talked about it and one evening Claire suggested that we try to sail Happy Adventure to Expo. When I laughed hollowly, she replied:

“No, Farley. I really mean it. There’ll never be a better time to go.”

I knew what she meant.

In February an incident had occurred which had ruptured the even tenor of our Burgeo ways. A female fin whale weighing about eighty tons, and heavy with calf, had become trapped in a salt-water pond near the settlement. Here she provided an irresistible target for the guns of a handful of Burgeo men until I interceded and stopped the shooting. Unhappily it stopped too late. The whale died from the wounds she received and the press, radio, and television across much of North America thereupon unleashed a barrage of contumely upon the whole of Burgeo. The bewildered residents were at first stunned by this attention from a world they did not know; and then became bitterly resentful. As was to be expected, much of the resentment was focused on me, and it was demonstrated in no uncertain manner when the rotting body of the monster was towed to a little harbour adjacent to my house (shades of Pushthrough), and left there, presumably as a suggestion that I mind my own business in future.

By the end of May the dead whale was only poisoning the atmosphere in the harbour proper, but I knew what to expect during the hot summer months, when eighty tons of meat and blubber would begin to decompose in earnest.

It did indeed seem like an appropriate time for us to depart from Burgeo.

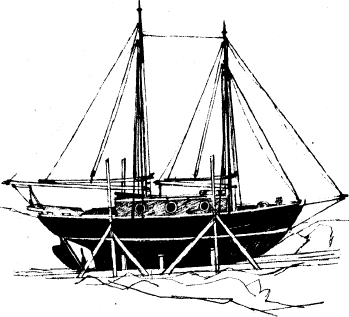

The problem was how to persuade Happy Adventure to agree. One day I received a press release describing how the seafaring heritage of the Atlantic provinces was to be represented at Expo by a replica of the famous Nova Scotian schooner, Bluenose. Now Newfoundland and Nova Scotian schooners have always been arch rivals. I took the release down to the slip where Happy Adventure drowsed and I read it to her, not once but three times, and slowly, to make sure she understood. And then I ruminated aloud about this intolerable affront to all Newfoundland vessels. Finally I suggested that the situation could be remedied if we voyaged to Expo ourselves.

“We’ll show them,” I said cheerfully as I slapped her buttocks, “won’t we, old girl?”

If she understood, she gave no sign. I could only hope I had gotten through.

We kept her on her slip while we prepared her for a voyage of just over fourteen hundred nautical miles. I hired Dolph Moulton, who was a sound shipwright, to help me put her in shape and the two of us, assisted at sundry times by every able-bodied man in Messers, laboured over her as few ships have ever been laboured over.

We left nothing to chance. We hawsed out all her seams and recaulked them. We stripped off and replaced every plank that seemed the least bit dubious. Then we coated the entire hull with a space-age epoxy glue, bedded canvas into it, applied another layer of epoxy, and gave the whole vessel a second layer of brand-new, one-inch, pine planking. We caulked this new outer planking, and applied three coats of copper paint below the water line and four coats of black paint above it. When we finished, the hull was about three inches thick and so strong the little vessel could probably have been dropped by a crane without spraining a rib.

There was no way she could leak. Nevertheless I played it safe. One Saturday I hired a score of little boys with buckets to fill her up with sea water while she stood on the slip. The job took them all day. In the evening Dolph and I and Uncle Josh and Uncle Art and a dozen other men sat around under her hull and watched for drips. Not one drop came through.

The satisfaction we felt was expressed admirably by Dolph.

“Tight me son? She’s tight as a maiden’s drum!”

She seemed tight all right, but I had been fooled so many times before that I was taking no chances. I had sent for, and we had installed two brand new pumps. One was a modern impeller pump of fabulous capacity, driven by a belt from the engine. Even if, by some freak of devilishness, she did manage to leak a little, I would be able to circumvent her suicidal tendencies.

We launched her off the following evening at high tide. She took the water sweetly and bobbed out to her mooring, where she lay lightly on the harbour looking as pretty as a tickle-ass (the local name for a kind of gull). When I rowed out to check her at ten o’clock there was no more than a pailful of water in her bilges. I went to bed that night to a sound sleep, confident that Happy Adventure would sink no more.

I was awakened early the following morning. Dorman Collier’s charming daughter was standing in our kitchen making throat-clearing noises. Sleepily I pulled on my trousers and came out to see what she wanted.

“Oh, Mr. Mowat,” she said, and there was a catch in her voice that showed she was close to tears, “Father says you’d best come quick. ’Appy Hadventure’s going down.”

From the kitchen window I could see my little ship. I could see her masts, her red-painted cabin trunk—and about six inches of her hull. Several dories surrounded her and her deck was alive with men and boys armed with pails, dancing a wild fandango. A curtain of flung water hung prettily about her.

By noon we had bailed her out to the bottom of the engine which we drained and refilled with oil. Being a good English diesel it started without trouble, and the impeller pump took over,, sending a fire-hose stream across the harbour. Happy Adventure had been foiled again—but only for the moment. It was now all too clear what her answer was to my hopeful suggestion that she might be willing to make the voyage to Expo 67.

We hauled her again, and went over her so carefully that I believe we actually checked every single nail hole. We found no indication of where the water was getting in. Completely baffled, Dolph suggested that we launch her off, stand pump watch on her, and wait for her to “take up”—and at those words a memory came surging through my mind. I remembered Enos Coffin standing on the end of the stage at Muddy Hole:

“Southern Shore boats all leaks a drop when they first lanches off…but once they been afloat awhile, why they takes up….”

We launched her off, and she took up the whole of Messers Cove during a ten-day period, and we pumped it all out of her again. By the end of two weeks we had begun to wear her down. The leaks grew smaller until, by the end of the month that it took to complete preparations for the trip, she was only leaking her normal fifty gallons a day.

Reactions to our proposed voyage varied considerably. The Newfoundland Establishment, which had found me something of a thorn in its side both at the municipal and at the provincial level, sent me encouraging messages of which this one is typical:

OVERJOYED HEAR YOUR PLANS STOP MY GOVERNMENT ANXIOUS ASSIST ANY POSSIBLE WAY EXPEDITE YOUR DEPARTURE

THE ONLY LIVING FATHER

The signature was a playful allusion to the fact that, as a result of Newfoundland’s late entry into Canada, Premier Joey Smallwood was indeed the only surviving Father of Confederation. The rest of them, including my own great-great uncle Oliver Mowat, had been decently buried for seventy years or more.

On the other hand my real friends were appalled at my intentions. Jack McClelland, who had long since concluded that Happy Adventure was little more than a floating coffin, sent me a wire which (although I did not know it for some months) originated as:

DONT BE AN ASS YOU ARE A SILLY BASTARD

but which reached me as:

DONT BE AN ASP YOU ARE A FRILLY BUSTARD

This wire gave me much food for thought, as I tried to puzzle out what difference it would make to Jack if I became a poisonous Egyptian reptile instead of remaining an Arabian game-bird.

When Jack found he could not change my mind, he made a heroic gesture. On the next steamer I received a crate from him which contained:

4 inflatable life vests complete with shark-repellent packs;

1 emergency shortwave radio of the Mae West type without any power tube;

1 case of distress rockets;

1 inflatable rubber lifeboat, certified by the British Board of Trade to carry twenty-five people.

This shipment was accompanied by a letter informing me that Jack intended to protect his investment in the boat, and in me, by personally accompanying Happy Adventure through the more dangerous stretches between Burgeo and Montreal.

The mere idea of this filled me with horror. The odds against our survival were, God knows, already about as heavy as they could be. Claire and Albert shared my concern, and both of them made it clear that the moment Jack stepped aboard was going to be the moment they stepped ashore.

By the time we moved aboard Happy Adventure on August first, my confidence in the whole venture had been severely eroded. What, two months earlier, had appeared to be the prospect of a pleasant voyage to Expo now loomed as an ordeal from which it seemed unlikely that any of us would emerge unscathed. My one remaining hope was that the weather, which had been atrocious since late May, would stay that way until October, giving me at least a semi-legitimate excuse for remaining snugly moored in Messers Cove until the whole idiotic scheme had been forgotten. The weather on the Sou’west Coast being what it was, I felt reasonably safe in publicly announcing that we would sail on the first fair-weather day.

Wednesday, August second, dawned fair. For the first time in three weeks there was no fog, although the edge of the bank that lives perpetually on the Sou’west Coast still lurked a few miles away. At 0700 hours, when I apprehensively stuck my head out the companion hatch (hoping against hope to find it a foul day) there were no fewer than fifty people of all ages lining the hills around Messers Cove.

South Coast Newfoundlanders are generally undemonstrative. The audience that almost circled the harbour was a quiet one, and patient. Nevertheless I was acutely aware of them. I could sense that they were waiting for something. Claire joined me in the companionway and after a brief look about her, she said:

“Well, I suppose we have to go. We don’t want to disappoint the audience.”

I said: “Yes. Well. I suppose we had. But first I think I’d better check the engine bedding bolts again…and I have to lay out my chart courses…and I’d better take Albert ashore for a run because it may be a long time before he gets another chance…and….”

I did all these things, and many more, but it was no good. The wind did not change. The fog did not roll back to cloak my blue funk in a comforting anonymity. The patient watchers on the shore did not go off about their business.

At 1400 hours I took a surreptitious drink from the bottle I kept handy in the engine room, poured a dollop over the side (breathing a heartfelt prayer at the same time) and tried to start the engine. The damned thing started like a shot. No further scope for evasive manoeuvres remained to me.

“All right!” I cried in a ringing falsetto voice to my crew. “Stand by…let go the moorings!”

Claire trundled forward, slipped the heavy bridle off the niggerheads and flung it overboard. I pushed in the gear lever. The engine thundered and the big propeller kicked a gush of water under the stern. Happy Adventure was under way.

The people on shore got to their feet and some of the younger ones began waving. Frank Harvey stood on the end of his stage with a conch horn and blew a lugubrious salute. For thirty seconds I felt the exhilaration that comes to every sailor, no matter how timid he may be, when he finally severs the umbilical cord that binds him to the land.

Then there was a hell of a jolt! It pitched Albert clean over the bows into the water. It nearly broke both my shins against the cockpit combing. It flung Claire against the mainmast. And it brought Happy Adventure to a dead stop.

The engine stalled, and there we were, utterly motionless, part of a silent tableau which seemed frozen into timeless immobility. It was as if some giant, unseen hand had reached out to stay us in our passing. Actually, though, it was the umbilical cord.

Our permanent mooring was designed to hold a large steamer during hurricane weather. A thousand-pound block of cement sunk in the bottom ooze was connected to the mooring buoy by a massive chain. Attached to the buoy was a bridle made of three-inch-diameter nylon rope. Now, I had forgotten that nylon floats—and had steamed right over the floating bridle. The propeller had picked it up and wound it tightly around the shaft.

Sim Spencer, my closest Burgeo friend, got into his dory and rowed out to us. Together we hung over the dory’s gunwale and stared down at the serpentine mess of black-and-yellow rope wound around the shaft. Sim shook his head.

“We’ll have to unshackle the buoy and haul the vessel back out on the slip to clear her, Skipper,” he said sadly.

Half an hour earlier I would have thought those were the sweetest words I had ever heard. Not now. It may have been shame, rage, or perhaps something more profound; something that even the most timid sailor may occasionally be privileged to feel: the realization that no real seafaring man ever really masters his fear—he only learns to live with it.

“I’ll be goddamned if I will!” I cried and, stripping off my clothes, I took my sheath knife in my teeth and plunged overboard.

This may not sound like much, but to the Burgeo people it was an electrifying act. They do not swim. There is little point in their learning the art because the sea thereabouts seldom grows as warm as thirty-eight degrees, and a man can only endure exposure to such a water temperature for a few minutes. When the watchers saw me plunge, stark naked, into those chill depths they believed I was gone for good.

I nearly was. The shock was so great I immediately lost my breath. I surfaced and was hauled back into the dory by a really anxious Sim who implored me not to try again.

Being already numb, the shock of my second plunge was not so severe, and I got down to the propeller and had begun to saw at the thick rope when Albert joined me. He nosed me aside and began to worry the rope with his teeth. I surfaced and was again hauled aboard the dory. I was ready to give up, but Claire leaned over Happy Adventure’s stern and in her hand was a glass full of rum.

“If you’re determined to commit suicide,” she said gently, “you might as well die happy.”

I went down three more times before the rope was severed. Albert went down at least twice as often and whether the credit should go to him or to me remains a moot question. He is a modest dog and seldom makes claims on his own behalf.

Happy Adventure was now free—and drifting rapidly down on Messers Island, a scant fifty yards away. Not stopping to dress I sprang to the engine, started it, and rammed it into reverse. Nothing happened. We continued to drift down upon the rocks. Bounding forward like a naked ape I let go the main anchor. The vessel brought up, swung, and came to rest with her stern so close to the rocks that Albert, who was still fooling about in the water, climbed a boulder and jumped aboard. He may have thought the whole manoeuvre was for his benefit.

This was finally too much for the stolidity of the audience. Among them all, I suppose, they had witnessed ten thousand vessel departures—but they had never witnessed one like this. Everyone who could reach a boat piled into one and in a few minutes the harbour was alive with dories, skiffs, and trap boats. They clustered around Happy Adventure like burying beetles around a putative corpse.

Several men explained to me, all at once, what the matter was. The shock of the sudden stop had jerked the propeller shaft out of the sleeve that connected it to the engine. The vessel (this was the unanimous opinion) would now have to go on the slip to be repaired.

But they reckoned without the spirit which, however briefly, still possessed me. Clad only in my underwear shorts (and I would not have been clad in those had not Claire insisted) I jumped into Sim’s dory, grabbed an oar, thrust it between the sternpost and the propeller, and began to lever with all my strength.

The oar snapped, and I savagely grabbed another. The clustered boats began to back away and there was an uneasy silence. The blade of the second oar split and pieces came floating to the surface. Uncle Bert Hahn, in the nearest dory, must have sensed what was going to happen next. He made a frantic attempt to back clear, but I leaned over Sim’s gunwale and snatched an oar right out of his hand. It was a good oar, one that he had made himself, and while Sim held his dory in position I slowly levered the shaft forward and into its sleeve again.

It took me only a few more minutes to tighten the set screws on the sleeve, restart the engine, and test the gears. This time the propeller turned as it should.

“Get up the goddamned anchor!” I shrilled at my crew. Almost before it had broken clear of the bottom I shoved the throttle full ahead, executed a turn that made Happy Adventure spin like a giddy girl, and we went rumbling off toward the harbour entrance, scattering little boats before us like herring.

I did not look back. When a man has made a really monumental asp of himself, he should never, never look back.