12

THE FOUNDERY

LONDON • IBIZA • SOUTH AFRICA

Never forget that justice is what love looks like in public.

DR. CORNEL WEST

The train clattered across Grosvenor Bridge on its way into Victoria Station. The sunlight was glinting from skyscrapers, their lines cut sharp into the cornflower-blue sky. My homecoming joy seemed to be resounding around the entire city. Just a few hours earlier, London had won the bid to host the Olympic Games.

I had been looking forward to this day for many weeks, and could hardly wait to see both our new London venue for the first time and my old friend Phil Togwell, still faithfully running 24-7 in the UK. On such a fine morning there was no hint anywhere, no whisper at all in the pristine skies above, nor in the glittering river below, and certainly not in the triumphant newspaper headlines littering the train, of the terror awaiting the evening editions.

I jumped from train to tube, unaware that other men elsewhere in the city were doing the same thing wearing backpacks loaded with homemade explosives. Four suicide bombers had chosen this particular day to destroy three underground trains and to blow the roof off a red double-decker bus, killing themselves and fifty-two innocent people, injuring 700 others. Parents, wives, and children had said casual good-byes that morning, never again to say hello. It was to be the bloodiest attack on London since the Second World War.

It’s hard to convey the contortions of disbelief and terror that seized us all that day. One bomb is terrifying. But then there was another. And another. And another. No one knew where or when the next device would explode. The entire city was paralysed with fear and rumour. The rest of the world was watching the story unfold online and on television.

Sammy called; I could hear the fear in her voice. She begged me to get out of London fast before the next bomb went off, before a skyscraper came down or a plane dropped out of the sky. But of course, I was stuck. The entire capital had been locked down, stations were closed, buses cancelled, airplanes grounded. There was nothing we could do, nowhere we could go.

We sat there in the middle of the hysteria, Phil and I, nervously gazing up at the forest of skyscrapers. It was a beautiful day, and if buildings were about to fall to the ground, we figured we’d rather be outside than buried below ground in the new subterranean Boiler Room venue. Sirens were screaming, police helicopters buzzing like hornets from A to B. In the end we did the only thing we could, the thing God had been calling us to do for more than half a decade.

Intercession is often instinctive and always important in the midst of any catastrophe, but at such times we may wonder what possible difference our prayers can make. There are at least four reasons why we sometimes fail to truly intercede in the face of terrible disasters:

- A limited worldview. All too easily we forget, or we doubt, that there is a spiritual reality at work behind the material tragedy unfolding on our screens. We find ourselves believing in ambulances more than angels, in the power of politicians more than the power of prayer. But the apostle Paul leaves us in no doubt: “Our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms” (Ephesians 6:12).

- A low self-esteem. We may also doubt our authority in Christ and the power that can be released by saying a simple yes to his will and no to the forces of evil. The apostle Paul says that God has positioned us alongside Jesus as rulers of the world: “God raised us up with Christ and seated us with him in heavenly realms” (Ephesians 2:6).

- Doubts about prayer. Deep down, we may doubt the power of prayer, questioning its ability to effect change. But the apostle James insists that “the prayer of a righteous person is powerful and effective” (James 5:16). And Jesus, who makes us righteous, and therefore makes our prayers “powerful and effective,” elsewhere promises to “do whatever you ask in my name, so that the Father may be glorified” (John 14:13).

- Practical questions about how to pray. Once we have remembered that there really is a spiritual battle, and that we really do have authority to make a difference, and that Jesus really has promised to answer our prayers, we may simply hold up our hands and say, “Yes, OK, fine, but I still don’t actually know what to say!” Understanding how to pray for the victims of a terrorist attack in London, or a war in the Middle East, or a tsunami in Asia can be terribly difficult. Many people believe that they ought to pray at such times, they probably want to pray, but they just don’t know how to wrap words around so much chaos and loss.

Over the years we have often found it helpful to focus our emergency intercessions at times of large-scale crisis on three particular groups:

- People afflicted. We ask God to comfort those who suddenly find their lives torn apart by grief, loss, fear, and trauma.

- Pastors and priests. We ask God to give courage to church leaders seeking to bring Christ’s presence and hope in the midst of trauma and profound questions of pain.

- Peacemakers, politicians, and police. We ask God to give clarity and wisdom to government agencies and NGOs, blessing and supporting their efforts to bring justice, reconciliation, and aid.

Sitting in the middle of the 7/7 attacks on London, Phil and I prayed as best we could. We asked the Lord to bring comfort to the many hundreds of people affected, the traumatised, injured, and suddenly bereaved. We prayed for pastors and priests as they began the solemn work of counselling, binding up broken hearts, preparing for funerals, wondering what words of hope and meaning they could possibly bring on Sunday. We prayed for peacemakers, for the police hunting down the remaining perpetrators, for the government ministers coordinating the emergency response, for the army of exhausted medics tending to the wounded.

The Prayer of Lament

The call to intercede at times of tragedy flows directly from the cross of Jesus. In those two intersecting beams we recognise that God identifies with —and participates in —human suffering, but also that he has overcome it. These two axes can also provide a helpful model for intercession.

First, the vertical post of the cross calls us to plant ourselves squarely in the troubles of the world. We choose to engage with the suffering of others —not to ignore it. We cry, “O my God, help! O my God, why have you forsaken us?” Such Good Friday prayers were easy in London that day as terror seized the city. In fact, they were automatic. Before we cry out for the afflicted, we should always try to pause to pray with them; to wait without any easy answers or guarantees. Intercession, at its most powerful, invariably begins with simple lament: a heavy sigh, silent tears, careful listening to a person’s pain without immediately speaking to solve their problem or correct their theology. Lament features in more than half the Psalms and an entire book of the Bible. It is a vitally important, often forgotten expression of prayer.

The Prayer of Authority

Of course, our call to intercede moves quickly from empathy to authority, from the downward trajectory of the cross to its horizontal embrace. Christ flings his arms wide over every human tragedy. His resurrection quivers with defiant hope over every disaster. We are Easter people for whom there are always new possibilities buried within even the greatest troubles. The cross proves once and for all that Satan’s worst atrocities can now, in Christ, become God’s best opportunities. It is an article of our faith that “in all things God works for the good of those who love him” (Romans 8:28). Unspeakable disasters, personal tragedies, and even terror attacks can somehow be redeemed by the cross of Christ.

And so we pray for his kingdom to come; we declare war on enemy forces; we stand against the evil that has been unleashed; we try to discern God’s will in the situation and insist upon its urgent implementation; we wield “the sword of the Spirit which is the Word of God” (Ephesians 6:17); we claim his promises and declare God’s truth; we listen to the Holy Spirit and allow him to focus our prayers onto particular people in the crowd. We may also seek out other Christians with whom to pray, forging spiritual alliances, because “if two of you on earth agree about anything they ask for, it will be done for them by my Father in heaven” (Matthew 18:19).

Phil and I sat there surrounded by the hysteria of 7/7, praying God’s peace and healing upon the city. Sirens were sounding, helicopters buzzing between buildings, but my old friend seemed the same as ever: kind, twinkly eyes, cockney accent, and that long, wiry goatee still reminding me of Narnia’s Mr. Tumnus. Finally, as the bombs stopped exploding and the initial terror began to subside, we ventured to begin the conversation we’d been anticipating all day.

I began to recount stories from our time in the USA, and Phil responded with equally exciting stories about all the new developments in England. He described a mysterious phone call six months earlier, from a businessman with properties throughout London who wanted one of his buildings to be used as a place of prayer. This Spirit-filled entrepreneur was sensing an urgent need for intercession and integrity right here, in the heart of the world’s greatest financial centre, long before anyone knew about the looming financial crisis and the terrifying bomb attacks on the city that day.

“So which one do you want?” he had asked Phil, spreading a map of the city on a table, covered in dots representing his extensive portfolio of potential venues. Phil couldn’t quite believe what was happening, but then his eyes fell upon a particular dot situated on the intersection of two well-named roads: Tabernacle Street and Worship Street. “I guess we’d better take a look at that one,” he said, grinning.

Although the building turned out to be an unimpressive 1970s-era block of offices, it was right on the edge of the Square Mile —London’s financial district. The basement was an extensive rabbit warren of subterranean rooms, stairs, and passageways, with loads of potential for prayer and studio space, offices, and meetings. Eventually, feeling a little shell-shocked, Phil wandered into the neighbouring pub, The Prophet, looking for lunch and somewhere to process.

“So what’s with all the religious names around here?” he asked the girl behind the bar.

“Huh?”

“The Prophet pub? Worship Street? Tabernacle Street?”

She’d clearly never given it a second thought. Why should she? But then, just as Phil was about to change the subject, a bespectacled gentleman with slicked-back hair, sitting at the nearby table, spoke up. “Forgive me,” he said, “but I couldn’t help overhearing your question. It’s all to do with John Wesley.” His manner was dignified and authoritative. “This is where he was based. The Foundery —the epicentre of Methodism for its first forty years —was just spitting distance from where we are seated now. It was an old cannon foundry originally, before Wesley got hold of it —hence the name.”

Phil had certainly heard of Wesley’s Foundery. For Methodists and revivalists around the world it is a place laden with almost mythological significance. He’d always presumed it was somewhere buried beneath one of London’s tangled back streets, but had never known precisely where.

“So how come you know all this?” he enquired.

“Oh, I do apologise,” the gentleman said, extending his hand. “How rude of me. I should have introduced myself. My name is Lord Leslie Griffiths. I am the superintendent minister at Wesley’s chapel, the one he built just up the road when the Foundery eventually burned down. My chapel was his base for the last eleven years of his life. People come from all over the world to visit and pray. But of course,” he smiled, clearly enjoying the irony, “the real heart of the Methodist revival is actually buried 200 yards down the road.”

Phil tentatively explained our vision to establish a centre for prayer, mission, and justice in a large basement we’d just been offered nearby in Tabernacle Street. It seemed trivial compared to the Foundery, but when he heard this, Lord Griffiths became animated. “Tabernacle Street, you say? Tell me, where in Tabernacle Street is your building, precisely?”

They left the pub together and strolled up the road, halting at the Boiler Room door. The minister let out a slight gasp.

“This,” he pronounced excitedly, “is the exact site, to the nearest yard, of the Foundery! Your worthy new endeavour is to be based on the precise spot where Methodism was born. Did you call it a Boiler Room? Well, that’s appropriate, because the fires of the Great Awakening were certainly once stoked right here!”

It was another bewildering moment of divine symmetry. Phil recounted the story to me, laughing at the improbability of it all, which made his eyes twinkle even more and his wiry beard quiver. What were the chances, we wondered, of picking a building at random from a city of 8 million people, and finding ourselves here on one of the most significant sites in British Christian history? And having been given the keys to such a place, what did it mean that we were here viewing it, at the precise moment of the city’s gravest attack in more than sixty years?

By late afternoon, most underground lines were nervously reopening, with armed guards at every station. The city continued to contort in shock, but investment bankers and commodity traders were beginning to return to their desks in the skyscrapers surrounding Tabernacle Street. Phil and I could see them through the windows far above us.

Unblocking an Ancient Well

Some 80 million Christians today from more than 133 countries and 80 denominations trace their faith back to the Foundery. This site was the heart of the greatest British spiritual awakening in perhaps a thousand years, an epicentre of world-shaking prayer, mission, and justice —a Boiler Room centuries before we came along. Did we dare to believe that we had been led to this remarkable location, like Isaac to the Valley of Gerar, to “reopen the wells that had been dug in the time of his father Abraham . . . and [to give] them the same names his father had given them” (Genesis 26:18)?

We began to research the history of the Foundery, trying to understand why God had set us down on its doorstep. The more we studied, the more familiar, more familial, those primitive Methodists became.

At the heart of all Boiler Room communities there are certain principles and practices that give shape to everything we do. We had always taken these practices to be distinctively ours, but now, in studying the history of the Foundery, we discovered that all six of our supposedly innovative values had, in fact, been modelled brilliantly by the Wesley brothers, on this very site more than 250 years earlier.

The Boiler Room Rule

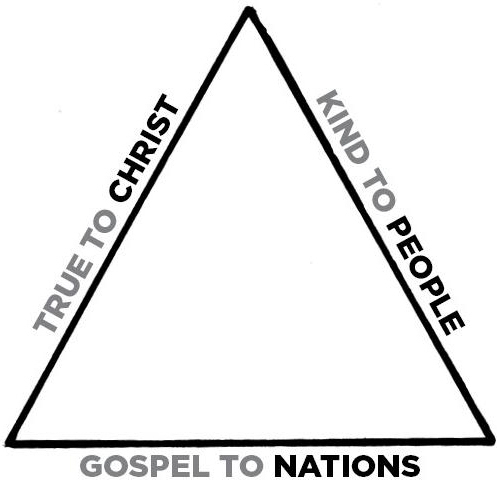

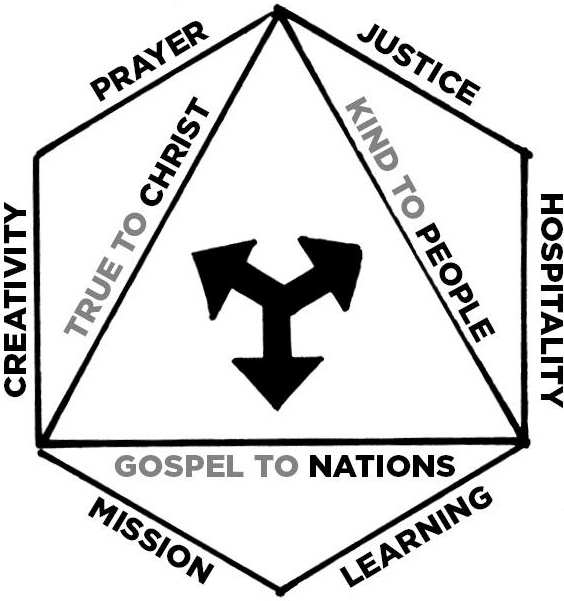

The six practices shared by all Boiler Rooms and modelled so powerfully at The Foundery are derived originally from the three great Christian priorities: to love God with all our hearts, to love our neighbours as ourselves, and to love the lost with the gospel (Luke 10:27; Matthew 28:19). The language we tend to use to describe these three priorities comes from our Moravian forefathers: We seek to love God by being “true to Christ,” to love our neighbours by being “kind to people,” and to love the lost by taking “the gospel to the nations.” Whatever language you use, these three loves summarise the universal call of Christ.

Boiler Rooms are distinctive (or so we thought, until we discovered the Foundery) because of the six practical ways in which we try to obey these three great commandments. Our Rule of Life can be depicted for the sake of memorability as a hexagon (the six practices) wrapped around a triangle (the three great commands of Jesus).

A. We seek to be true to Christ through:

- 1. Prayer and worship. We seek to be a house of prayer for the nations, because we know that human beings are designed to walk and talk with God, and to glorify him for ever.

- 2. Creativity. We seek to provide studio space for the arts, because God’s creativity is worth celebrating with all the imagination and colour, flavour, and melody he has given us.

B. We seek to be kind to others through:

- 3. Hospitality. We seek to be an open table offering radical hospitality, because God has welcomed us into his family and calls us to make space for others sacrificially in our hearts and our homes.

- 4. Justice and mercy. We seek to be centres for social justice and mercy, because Jesus cares passionately about those on the edges of life, and he has sent us to be good news for the poor.

C. We seek to be loyal to the gospel through:

- 5. Evangelism. We seek to be mission stations for evangelism, because the gospel is good news for the salvation of every single person on the planet.

- 6. Learning. We seek to be academies for education because Jesus is still in the disciple-making business, calling us to lifelong learning and to train others in his ways.

We were astounded to discover the extent to which the early Methodists had outworked all six of these practices on Tabernacle Street.

A house of prayer. In Wesley’s day the Foundery functioned as a house of prayer at the heart of the burgeoning British (and American) Awakening. It is hard to overstate the extent to which Methodism was founded and fuelled by persistent and expectant intercession. John Wesley, who had personally experienced the Moravian prayer meeting in Herrnhut, and had been baptised in the Spirit at an all-night prayer meeting nearby in Fetter Lane, organised and led daily prayer meetings at the Foundery. As if this wasn’t enough, Wesley would also arise daily at 4 a.m. to intercede for four hours before the day began. In later life he might have relaxed this arduous daily regime, but instead he extended it, praying for up to eight hours a day. We can only guess what deals he struck with the Almighty during those many thousands of hours of prayer.

A place of creativity. The Foundery was a house of prayer but also a context for extraordinary creativity. Most notably, Charles Wesley wrote many of his hymns in this location. Tabernacle Street would often have resounded with voices singing one of his latest compositions. The composer George Frideric Handel lived on Brook Street, a twenty-minute ride from the Foundery, and may have invited John Wesley to attend a performance of his new oratorio Messiah. “There were some parts that were affecting,” recorded the thirty-nine-year-old preacher of Handel’s masterpiece, before unfortunately adding, “I doubt it has staying power.”

Evidently, it was thanks to Charles Wesley’s artistic sensibilities and not those of John that many of the most-loved songs in history found their first rendition at the Foundery —timeless hymns ranging from “And Can It Be?” to “Love Divine, All Loves Excelling.” It is a tantalising possibility that on Christmas Day 1739, just a month after John Wesley’s first sermon in the Foundery, the walls and cobbled stones of Tabernacle Street heard the very first public rendition of that greatest of carols, “Hark the Herald Angels Sing.”

A home for hospitality. From the late 1740s, the Foundery served as an almshouse providing “accommodations to 9 widows, 1 blind woman, 2 poor children, and 2 upper servants, with a maid and a man.” Wesley insisted that those who stayed as his guests should always dine with the occupants of these poorhouses, eating exactly the same food and sitting at the same tables. There was to be no hierarchy. The great and the good mingled with pilgrims and the poor as they flocked to this building from around the country. Wesley insisted, in the words of St. Benedict, that “all who arrive as guests are to be welcomed like Christ.”[66]

A centre for justice and mercy. The Wesleyan revival was marked by irrepressible social enterprise. The Foundery offered a Friday clinic providing primary healthcare for the sick, a school for the poor, and one of the world’s first lending banks for families in crisis. In its first year alone, the Foundery Bank issued micro-loans to 250 families. The Wesleys also operated a ministry to the inmates of nearby Newgate Prison, from which Charles would often accompany condemned prisoners to the gallows on Tyburn Hill, offering comfort and hearing their final prayers. John was compelled to go out begging for money, knocking on door after door in the neighbourhood requesting financial support for their work amongst the poor. In 1774, four years before the destruction of the Foundery, John penned Thoughts upon Slavery, an excoriating condemnation of human trafficking which he described as that “execrable sum of all villainies.” His final letter, written on 28 February 1791, when he was eighty-eight years old and just six days before his death, was addressed to William Wilberforce, urging the famous abolitionist to persevere in his fight to the end.

An academy of learning. The Foundery housed a library, a “band room” in which 300 people could be taught, and a school offering education to the local poor. It was also an auditorium for daily preaching, teaching, and theological education. Ideas mattered deeply here; there was no hint of anti-intellectualism in its corridors. On one occasion, a theological dispute provoked followers of George Whitefield to picket the Foundery. They handed out tracts condemning Wesley’s teaching that anyone, anywhere can be saved. They believed that salvation is restricted to a preordained minority. John promptly stood up before the gathered congregation and demanded to know which ones of them had received one of these tracts upon entering. Sheepishly, people pulled the papers from their pockets, whereupon Wesley led them in tearing the tracts to shreds and ceremonially throwing the pieces aloft. Then, as the confetti fell like snow, they sang one of Charles Wesley’s most adamantly Arminian hymns, declaring unequivocally that “for all he has the atonement made”:

Arise, oh God, maintain Thy cause!

The fullness of the gentiles call;

Lift up the standard of Thy cross,

And all shall own Thou diedst for all!

A mission station for evangelism. The Foundery was preeminently a mission station in which —and from which —the gospel was preached. Lay evangelists were trained here and sent out to preach the good news of Jesus, establishing a national network of discipleship classes. It was from this evangelistic base that John Wesley rode more than 250,000 miles nurturing Methodist societies the length and breadth of the nation, planting churches, developing an arterial system of preaching circuits, and relentlessly proclaiming the gospel for the new urban masses of the Industrial Revolution.

Despite its many remarkable ministries, the Foundery remained a primitive venue. Buckets had to be deployed to catch the rainwater falling through the building’s defective roof. Wesley was continually forced to fundraise until, in the end, the Foundery burned to the ground. Wesley moved up the road to build a grander chapel, and today’s ugly office block was eventually built on the historic site.

Our supposedly radical ideas for Boiler Rooms as houses of prayer, mission, and justice, creativity, learning, and hospitality were clearly nothing new at all. These simple missional-monastic communities are, in fact, mini-versions of Wesley’s great Foundery. And now, whether by life’s strange symmetry or the direct intervention of God, we found ourselves on the actual site of the original prototype, with a vision to do the things that the Wesley brothers had done so brilliantly in this location, some 250 years earlier, in ways that had changed the destiny of entire nations. Phil and I stood there on this historic site on that particular day, humbled by the past and sobered as the sound of sirens in the streets overhead continued to call us to pray.

Seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you into exile, and pray to the LORD on its behalf, for in its welfare you will find your welfare.

JEREMIAH 29:7, NLT

Brian and Tracy Heasley were continuing their nocturnal rhythm, rescuing people in the Vomit Van, handing out their Jesus Loves Ibiza Bibles, ministering to long-term workers on the island, and praying through the night in shifts with the team at their 24-7 centre. For several years they had also been trying to build connections with the town’s West African sex workers, but with little success. The women’s pimps prowled around suspiciously nearby, and the women themselves were too busy making money, performing sex acts in darkened doorways and parking lots, to waste time with Christians. Some of them were just too nervous to talk. But then, one particular night, as the team in the prayer room was interceding for these women, there was an unusual surge of faith, a conviction that their prayers had finally “broken through.” The girls on the team went out onto the streets that night with great expectancy, hoping to meet some of the women for whom they’d been praying. For the first time in years, the women responded warmly, opening themselves to conversation and even to prayer.

Friendships grew surprisingly quickly after this long-awaited breakthrough, and the Heasleys decided to establish a chaplaincy for the island’s sex workers. Surprisingly, most of these women considered themselves Christians. They would nod enthusiastically whenever they were asked if they would like prayer or a personal relationship with Jesus. One of the women began to come to the Boiler Room meetings. She had the most beautiful voice and before long was helping to lead the worship. The sight and sound of this broken woman singing the song “Beautiful One” consistently reduced everyone to tears. But of course it was also troubling, and Brian called me one day to ask if it was OK to have a prostitute leading worship.

I paused. It wasn’t a question I’d ever been asked before. I wondered why she couldn’t just stop prostituting herself if she really wanted to follow Jesus.

Brian explained that it wasn’t as simple as that. Of course they were trying to help her get free from the sex trade. But she had a madam to whom she owed massive debts. And she was on the island illegally, which meant that she couldn’t just get a normal job.

As Brian talked, I realised anew just how messy and morally ambiguous discipleship can become on the front lines of mission. “It certainly sounds like a good problem to have,” I said, as brightly as I could.

“Thanks for nothing,” said Brian.

When Tracy and other female team members offered to pray with these broken women on the streets, some would immediately take a white handkerchief from their handbags and place it on their heads to receive the blessing. It always seemed such a quaint thing to do, utterly incongruous in the neon-lit streets of San Antonio. It could almost have been amusing if it hadn’t been such a poignant indication that behind their current predicament there lay a half-forgotten, happier, churchgoing past.

The problem for many of these women was that they had been trafficked in one way or another. Some may have had drug addictions to feed, some were trying to pay off impossible “debts” owed to their traffickers, others lived in fear of their madam’s “juju” curses, and many were diligently sending money home to their children, understandably pretending that they had good jobs in Europe. Every story was utterly heartbreaking.

Over the years, Brian and Tracy’s primary prayer for all the ordinary partygoers, musicians, and promoters of Ibiza had been very simple: that they would come to know Jesus. Baptism services in the island’s crystal-clear seas were always joyous occasions because they marked the start of a whole new life. But the normal principles of mission didn’t seem to apply to these West African sex workers. If acknowledging your sins in prayer, apologising, and beginning a relationship with Christ is all that it takes to become a Christian, these women would happily “get saved” every day of the week and twice on Sundays. Yet they didn’t seem very safe or saved as a result. Salvation for them seemed far more practical and literal than it might for those whose lives are more privileged and free. They needed to be saved for sure, but it was not just from their own sins but also from the people and systems that controlled their choices, from the authorities trying to deport them, from the cruel powers driving them to prostitute themselves in the first place. Their problems, it seemed, were not primarily spiritual but financial, legal, and even political.

Brian and Tracy were starting to realise that if any one of these women should ever truly want to be free, it would probably be necessary to smuggle her off the island and set her up in a safe house on the Spanish mainland. She might need help getting free from addiction and the years of brutal trauma. If she should choose to stay in Europe, perhaps because her children back home would starve without their current levels of provision, she would need a safe job that could pay almost as much as prostitution. We would probably have to create these jobs for them, since most didn’t have the papers to get work officially. Along the way we would also probably have to set up a savings scheme to help them reach the levels of financial stability which could ultimately enable them to return home to a new life with their children and their heads held high.

Such an illicit approach to redemption might well be questionable legally and even ethically, but the alternative course of action might have perpetrated an even greater injustice, either by ignoring their plight altogether, or by condemning them to deportation, social stigma, and extreme poverty back home. When God freed the Israelites from captivity in Egypt he did it literally —not just metaphorically. Similarly, when Jesus forgave the sins of the quadriplegic man lowered through the roof he proceeded to heal him physically too. John Wesley and William Wilberforce understood that it wasn’t enough just to help slaves believe in the right things, when their most urgent need was clearly to be freed from the physical bonds that controlled them. Down the ages, it has always been the tendency of the rich to reduce salvation to a purely spiritual experience. But if you’re hungry you need real bread before you will consider the heavenly variety. If you’re in chains you take the Bible verses about freedom very literally indeed.

As Brian and Tracy wrestled with the complex, practical implications of salvation for these West African sex workers, they realised more than ever that the consequences of the gospel are profoundly structural as well as spiritual. The cross of Christ must be brought to bear on the systemic strongholds of sin within societies, as well as the individual realities of personal repentance and morality.

Óscar Romero, the Archbishop of San Salvador who was assassinated for speaking out against injustice, warns us against an overly spiritualised and individualised approach to the gospel:

It is very easy to be servants of the word without disturbing the world: a very spiritualized word, a word without any commitment to history, a word that can sound in any part of the world because it belongs to no part of the world. A word like that creates no problems, starts no conflicts. What starts conflicts and persecutions, what marks the genuine church, is the word that . . . accuses of sin those who oppose God’s reign, so that they may tear that sin out of their hearts, out of their societies, out of their laws —out of the structures that oppress, that imprison, that violate the rights of God and humanity. This is the hard service of the word.[67]

The 7/7 attacks left a lasting scar on London; many of its victims would never fully recover. But eventually the national terror alerts were reduced from red to amber. It was becoming clear that God had placed us here, on the edge of London’s financial district, not just to celebrate the glorious history of the Foundery, but also to respond to the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression of the 1930s. The world’s markets were suddenly in free fall all around us. Invincible banking institutions were toppling, and systemic corruption was being exposed in our own new backyard. Finding ourselves in the middle of all this, we cried out as best we could for God to restore integrity, to bring down Mammon, to flood the boardrooms and trading floors of London and Wall Street, Tokyo, Hong Kong, and Frankfurt with his spirit of holiness, and to repopulate them with men and women of good conscience. We prayed for the peace and prosperity of the city for the sake of the poor.

Our prayers often seemed weak and even a little absurd in the face of such vast global events, and yet we knew beyond any shadow of a doubt that God had mandated us to partner with him in prayer and to do it here, in this particular place and time. Whenever we felt insignificant and naïve, the history of the Foundery would reassure us that simple prayers and quiet deeds can change the world.

Manenberg

As Phil Togwell continued to lead the charge in London, I tried to do the same elsewhere, talking as often as I could with leaders like Jon Petersen in America, Kelly in Mexico, Brian in Ibiza, and in South Africa, new friends Pete and Sarah Portal. Together they had galvanised a team to plant a community in Manenberg, an apartheid-era “coloured” township blasted by drugs, gang warfare, and one of the highest murder rates in the country.

“How are you guys doing?” I asked Pete one day, via Skype.

“Not so great. Rough day. How are you?”

“Me? Well, I guess I’m having a bad day too!” I’d argued a bit with Sammy and knew that I needed to apologise, the car was playing up, and emails were coming in faster than I could possibly reply.

“What’s up?” he asked me kindly.

“You go first,” I said. “Spill your guts.”

Pete told me that open warfare was erupting once again between the gangs of Manenberg. In fact, he’d woken up that very morning to a stark warning: “Be careful today. There’s been heavy shooting.” I knew he wasn’t exaggerating the dangers; I had visited Manenberg myself and seen a bullet that had come through his office window a few months earlier. Most of their prayer weeks had been punctuated by violence. But this latest battle, Pete said, was proving to be the worst one yet. For the first time ever they’d been wondering about shutting down the prayer room.

One of the people killed in the previous night’s shootings had been Pete’s friend Blinky, a crystal-meth user who’d approached him in the street wanting to be freed from his addiction. Pete had prayed with Blinky and had led him to Jesus. But he’d returned to his life with a gang called the Jesters, and now it was all too late. Blinky was gone.

“So, uh, yes, it’s not been a great day so far.” Pete’s voice trailed off.

“I’m so sorry,” I whispered.

I was far too ashamed to admit how trivial my problems were compared to his.

Two days later I called Pete again. I’d been praying for him and the community in Manenberg a lot, and I was anxious to hear how they were doing.

“Oh, it’s been a much better day,” Pete told me cheerily. He’d been prayer-walking around the township with a friend, symbolically waving white flags, declaring peace over the troubled city in Jesus’ name. Along the way they’d met an old man in a baseball cap with a weathered face, watery eyes, and a white beard. His name was Uncle Henry. He was sitting with a pair of crutches.

Uncle Henry had severely injured himself several months earlier by falling off a roof doing repairs. Pete offered to pray for him, and Uncle Henry was instantaneously, miraculously, completely healed. He leaped to his feet, yelping with delight, and began jumping, dancing, and waving his crutches in the air, grinning from ear to ear.

“Do you know who just healed you?” Pete asked him, laughing.

“No!” replied Uncle Henry, still dancing.

Pete told him about Jesus, and Uncle Henry whispered a prayer of surrender between great heaving sobs of thanksgiving. Picking up his crutches, Uncle Henry danced home rejoicing, to the amazement of everyone he knew.

It had been an eventful three days by anyone’s standards. Pete had been dodging bullets on Monday, grieving the tragic loss of a friend, and on Wednesday he’d seen a crippled old man healed and saved. One minute in Manenberg Pete’s heart was breaking, and the next it was bursting with joy. Several years earlier, when he had abandoned a good job as a researcher at the BBC after graduating with a top degree from Edinburgh University, there were probably a few well-meaning friends who thought he was throwing his life away for the sake of an impoverished community of no-hopers on the other side of the world. But in fact Pete had found life to the full (John 10:10), the kind that a television researcher can, well, only research. The kind of life that makes a difference in the world.

When he first arrived in South Africa, Pete had spent the best part of a year simply prayer-walking around Manenberg, allowing his heart to break for its evident pain. During that year of prayer, Pete led four people to Jesus, but three of them had fallen away and returned to their previous lives. But he’d also met Sarah, a beautiful Capetonian with blue eyes and brightly coloured feathers in her raven hair. They got married and spent her inheritance buying a house in Manenberg, a place where few white people dared to go, let alone live. “If you give me everything you’ve got,” the Lord had told them, “I’ll give you everything I’ve got.”

Sarah set about making their new township home beautiful with brightly coloured walls, a garden of raised flower beds, a prayer room, and an entire section where men who want to get free from drugs and gangs can live in safety. It was a home worthy of the beautiful community Pete and Sarah were determined to grow with their friends in the streets of Manenberg.[68] Like Kelly in Boy’s Town and Brian in Ibiza, they were experiencing remarkable breakthroughs as they sought to bring good news to the poor.

They were also beginning to ask important questions about the structures of injustice afflicting so many lives. Uncle Henry, for instance, had been dramatically healed and saved, but he wasn’t interested in joining their community to receive further discipleship, so how was he ever going to truly change? It was becoming increasingly clear to Pete and Sarah that the answer for Manenberg was more complicated than just getting everyone healed and praying a prayer. Something was wrong with the place systemically, and it was only going to be changed by a profound cultural shift. Their acts of daily mercy on the ground would amount to little more than sticking plasters on the wound until God’s healing was applied to Manenberg itself.

The broken people with whom we were increasingly dealing, in Ibiza, in Boy’s Town, in Manenberg, and around the world, needed this kind of help —practical provision as well as spiritual truth, justice as well as charity, long-term hope as well as short-term help. If we were really serious about “justice for the poor,” it was going to require more of us than just a little costly kindness and compassion. The Heasleys were learning this in Ibiza amongst the West African sex workers; the Portals were realising it too in the crossfire between Manenberg’s gangs; and Kelly could see it in Boy’s Town, where the mafia could make or break you and where each person she managed to rescue just seemed to be replaced by another victim. She knew that this weary flow of inhumanity would continue unabated until Boy’s Town was properly regulated or, better still, knocked to the ground.

Kelly had invited me to visit her in Reynosa, and I was keen to go. I wanted to see the new Boiler Room complex she was building and to meet some of the wild characters she’d so often described. I suppose I’d expected Boy’s Town to be dark, depressing, and ugly, and yet, within its concrete walls, I was about to experience a moment of luminous beauty.

SELAH

Do all the good you can,

By all the means you can

In all the ways you can,

In all the places you can,

At all the times you can,

To all the people you can,

As long as ever you can.

JOHN WESLEY

Thank you, Father, for the radical example of John Wesley. Raise up such women and men again in this generation, to pray as he prayed, to preach as he preached, and to fight injustice too. Amen.

There is not a square inch of domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is sovereign over all, does not cry: “It is mine!”

ABRAHAM KUYPER, FORMER DUTCH PRIME MINISTER