IN 1928 HOLLYWOOD BEGAN PRODUCING “100 PERCENT TALKIES” alongside synchronized films and part-talkies. Filmmakers who chose to use music in the 100 percent talkie faced questions similar to those for part-talkies. Does an all-talking film need to be explicit at all times about where the music is coming from? If a film uses diegetic song performances, must the film mark a clear distinction between these performances and nondiegetic music? If so, how can this be achieved? Should the music’s volume be lower during dialogue sequences, or should it remain at the same level as it generally did in the silent era? Must the continuous music practice of the silent era be maintained, or is intermittent music an acceptable solution? If intermittent music is used, what logic dictates where it should be placed in the film? Finally, what role, if any, should musical motifs play in the all-talking film?

The answers to these questions varied widely, not only from year to year but also from film to film. While some general musical tendencies can be detected, the period from 1928 to 1931 was also rife with experimentation and roads not taken. To demonstrate the diversity of film music, as well as some of the common approaches in the period, this chapter offers a series of case studies, as well as an outline of some common practices. My focus here is on nonmusicals from 1928 to 1931; chapter 4 addresses the particular case of the early film musical. Because the exhibition season in the early sound era ran from Labor Day to Memorial Day,1 this chapter considers the 100 percent talkie only through May of 1931. Chapter 5, in turn, addresses the use of film music in the following two seasons.

This chapter’s assessment of film music in 100 percent talkies is based on a viewing of the nonmusicals released from July 1928 to May 1931 listed in the appendix. I begin with an analysis of two early all-talking films—Lights of New York (July 1928) and The Squall (May 1929)—that contained extensive music and provided early, yet very different, film music strategies. Shortly after the release of The Squall, the film industry substantially reduced its use of nondiegetic music. After examining this reduction and offering explanations that differ from the standard scholarly account, I outline several musical practices that filmmakers used regularly from 1929 to 1931. In many cases nondiegetic music was not eliminated but rather was deployed in ways that minimized the audience’s awareness of its presence. I then examine two films from 1930—Liliom and The Big Trail (both October)—that feature unusually complex uses of nondiegetic music for the period. Finally, I examine Cimarron and City Lights (both January 1931)—two of the only films from the period to enjoy substantial attention from film music scholars—within the context of broad film music practices from 1929 to 1931. When situated historically, City Lights can be seen as an anomaly, while Cimarron’s deployment of nondiegetic music—despite regular claims to the contrary—was relatively typical for the period.

The findings in this chapter directly challenge decades of film music scholarship and demand a reconceptualization of the history of film music from 1928 to 1931. As discussed in my introduction, the prevailing view among film music scholars is that the period featured the complete or near complete reduction of nondiegetic music, thus suggesting that nondiegetic film music held little importance for the period’s filmmakers. This chapter presents an avalanche of filmic examples that feature nondiegetic music. Certain films from 1928 to 1931 explored nondiegetic music’s uses in sound film in substantial and meaningful ways.

EARLY 100 PERCENT TALKIES: LIGHTS OF NEW YORK AND THE SQUALL

From the beginning, approaches to music in the 100 percent talkie were diverse. This becomes evident when considering two early Warner Bros. releases: Lights of New York (July 1928) and The Squall (May 1929). Both films feature efforts to incorporate the near continuous music practices of silent film, but the films differ in the extent to which they retain this style in the face of a recorded performance aesthetic and the desire for a diegetically comprehensible sound space. Where Lights of New York’s score enters nondiegetic terrain cautiously and makes numerous concessions to the film’s diegetic performances, The Squall displays a more concerted effort to maintain silent film accompaniment practices.

Telling a contemporary gangster story that, as an introductory intertitle states, “Might have been torn out of last night’s newspaper,” Lights of New York centers on two men—Eddie (Cullen Landis) and Gene (Eugene Pallette)—who inadvertently team up with two bootleggers in an effort to make money in New York City. Thinking that they are going into a legitimate business, Eddie and Gene soon discover that Gene’s barbershop is merely a front for a speakeasy known as the Night Hawk. The unscrupulous speakeasy manager known as “Hawk” (Wheeler Oakman) convinces Eddie to use his barbershop to hide illegal alcohol that has been linked to a police murder. Hawk plans to pin the murder on Eddie, but Eddie catches wind of the plot. In a dramatic scene in the barbershop, Hawk pulls a gun on Eddie but a mysterious assailant then kills Hawk. In the final scene Eddie is nearly arrested for Hawk’s murder before the real murderer—Hawk’s jealous former girlfriend—turns herself in.

Upon its release in mid-1928, Lights of New York enjoyed the distinction—advertised heavily by Warner Bros.—of being the first “all-talking” film. Though the film was a tremendous box-office success, today it serves mainly as a poster child for the static camera and stunted dialogue of the earliest sound films. To date, film music scholars have not attended to Lights of New York,2 perhaps assuming that nondiegetic music would not have played a role in an early and awkward sound film. But music constitutes a regular and extensive presence in this film. All of the sequences contain at least some music, and in many scenes the music plays continuously underneath dialogue. Since it was released two months before the dialogue-laden Singing Fool (September 1928), Lights of New York likely constitutes the first instance of extensive dialogue underscoring.

The decision to use accompaniment music in Lights of New York was a carryover from previous types of films. In mid-1928 a film—whether a silent or early synchronized film—virtually always featured continuous or nearly continuous music. Yet as with the part-talkie, the addition of dialogue required filmmakers to face questions about diegetic/nondiegetic distinctions, appropriate balances between music and dialogue, and whether to continue the late silent-era practice of using musical motifs. Lights of New York’s responses to these issues were sometimes contradictory, indicating that the filmmakers did not always have a consistent sonic strategy for this early talking film.

If music was to be heard through much of this film, did it need a source in the image? Lights of New York hedges its bets on this question by initially tying music to an obvious diegetic source before gradually presenting music that is less and less plausibly diegetic. This tactic begins during one of the earliest shots in the film. The image presents a radio while the soundtrack features the popular 1917 tune “Where Do We Go from Here?”—a title that reflects the two bootleggers’ desire to move away from their small town and back to New York City. When one character asks the other to switch off the radio, all music promptly stops for the duration of the scene. Because this abrupt cessation of the music draws the audience’s attention toward the song and its clear diegetic source, viewers might assume that the film as a whole will provide music with sources in the image.

Subsequent scenes, however, contain music that becomes progressively more difficult to locate. The next two scenes feature music during conversations in a hotel lobby and then an apartment. While both locations could conceivably contain a radio, no radio is visible, meaning that the diegetic status of the music has been rendered less clear. Further pushing the music toward diegetically ambiguous territory, the filmmakers use a different style of music in the lobby and apartment. The lobby music includes the 1902 song “In the Good Old Summer Time,” which, like the song heard on the radio at the beginning of the film, is an older popular tune and is thus easy to interpret as another radio song. The music in the subsequent apartment scene, however, features a fuller range of instruments, a slow pace, and a far less pronounced rhythm—it is much closer to a classical than a popular idiom. Classical music was heard frequently on the radio during this period, but Lights of New York’s shift in musical style still marks the classical music as potentially belonging to a different sphere. Moreover, this music conveys a sentimental mood that almost too conveniently matches the heartfelt conversation between Eddie and his mother to be diegetic. A few scenes later, the score finally moves into clear nondiegetic territory by featuring orchestral music during a conversation in Central Park. Unlike part-talkies like The Singing Fool or Weary River (January 1929), Lights of New York’s music only gradually eases toward nondiegetic territory, thus making its eventual nondiegetic identity harder to detect.

After the scene in Central Park, the filmmakers face a new musical question during a lengthy sequence inside the Night Hawk club. Scenes inside the nightclub alternate between musical numbers performed in the stage area and conversations advancing the plot that take place in other locations, most notably Hawk’s office. As Rick Altman points out, during conversation scenes inside Hawk’s office, the diegetic numbers are presented like an on/off switch: the music plays full blast when the door is open, but then—despite the fact that Hawk’s office is right next to the stage area—it is reduced to nothing when the door is shut.3 This situation creates a new problem for nondiegetic music. When Hawk’s door is closed and diegetic music ceases, should nondiegetic music reemerge on the soundtrack? In other words, which model rules the roost: the continuous music model of silent and early synchronized sound films or a soundtrack that features only diegetic music?

Unlike part-talking films, Lights of New York’s filmmakers avoid nondiegetic music in spaces featuring performances. Since the film audience knows that diegetic music is being performed elsewhere in the nightclub, a return to nondiegetic music during the nightclub sequence could create confusion over whether such music contains a sound source within the diegesis. Invested in a musical model that directs attention away from vexing diegetic and nondiegetic questions, the filmmakers are willing to jettison the nearly continuous musical model that had dominated the late silent era. Only after the end of the Night Hawk sequence do the filmmakers return to a nondiegetic music aesthetic. Nondiegetic music, though plentiful, consistently takes a backseat to diegetic sound concerns in Lights of New York.

Though Lights of New York contains a consistent strategy for when to use nondiegetic music, the same cannot be said for its volume-level balance between music and dialogue. As with Warner Bros.’ The Singing Fool, music continues to play at a rather high volume during dialogue sections, sometimes even threatening to exceed the volume of the dialogue. Yet at other times, the music does adjust its volume for dialogue. Altman points out that during the Night Hawk sequence, dialogue sometimes occurs when the music volume is not at fortissimo (a very high volume) and that at one point the music volume noticeably dips for an important conversation.4 One might add that conversely, music sometimes swells during climactic moments when no one speaks. For instance, when Eddie—whom Hawk and the audience thought had been killed—walks into the barbershop at the film’s climax, this surprise is amplified by an increase in music volume. The volume then lowers again to accommodate the next line of dialogue. Inconsistency, rather than a unified strategy, characterizes the respective volume levels of music and dialogue.

Perhaps most surprisingly, music for Lights of New York does not feature the motif strategies that served as a structuring principle for numerous late silent and early synchronized scores. Lights of New York’s filmmakers avoid the use of strong, easy-to-detect melodies, sometimes burying the melody within dense harmonization. With one exception,5 no cues repeat in this film. Instead, the film provides what might be termed “general mood music”—sentimental music when Eddie and his mother talk, ominous music for a murder, and so on. This music makes few alterations for specific characters’ actions or lines of dialogue. The score changes its musical style only for major narrative mood shifts, such as a sudden tempo escalation when Eddie introduces his mother to unscrupulous bootleggers, or soaring utopian music when Eddie realizes he has been saved from a murder charge. The lack of themes may well be attributable to the film’s low budget and short production schedule, as filmmakers likely had little time to devise a thematic logic for the film. But it constitutes another way in which Lights of New York separates itself from its silent film predecessors.

Ultimately, Lights of New York constitutes a conflicting assortment of late silent accompaniment practices and on-location recording aesthetics. Music sometimes plays at a steady volume—as it generally did in the silent era—yet at other times it dips to accommodate dialogue. Some scenes contain silent-style continuous music, yet the filmmakers sometimes jettison musical accompaniment for the sake of diegetic sonic clarity. Musical themes—a staple of silent film music—are abandoned in Lights of New York, perhaps out of fear that nondiegetic themes might conflict with the showcasing of diegetic sound. As I indicated in chapter 1, motifs have the potential to draw attention to the presence of an external (nondiegetic) narrator who guides viewer response. Lights of New York, through its lack of motifs, actively avoids drawing attention to such an agent, instead highlighting diegetic musical performances and dialogue.

By itself, Lights of New York might suggest that the 100 percent talkie immediately broke with the thematically driven, continuous music practices of late silent, early synchronized, and part-talking films. Yet film style seldom moves in wholly unified directions, especially during the early years of a new technology. In May of 1929 Warner Bros. released The Squall, a film that features a more concerted effort to retain a silent film aesthetic in the face of the increasingly popular 100 percent talkie.

Set in Hungary, The Squall stars a young Myrna Loy as Nubi, a stunning yet morally questionable gypsy woman. Believing Nubi to be a Christian by birth rather than a full-blooded gypsy, a trusting farming family rescues her from an abusive gypsy man. Once she enters the family’s home, however, the dark-skinned Nubi uses her exotic beauty to turn men’s heads and wreck their previously stable relationships with their exclusively white partners. Nubi first breaks up the relationship between the servants Peter (Harry Cording) and Lena (Zazu Pitts). Next, she turns the head of Paul (Carroll Nye), a young man who was previously interested in Irma (Loretta Young), and she even receives attention from Paul’s father, Josef (Richard Tucker), who is married to Maria (Alice Joyce). As the men begin to argue and connive against each other, Nubi revels in the attention that she receives and the family discord that she causes. Ultimately getting wise to Nubi’s narcissism and less-than-honorable intentions, the family is only too happy to return Nubi to the gypsy man, who reappears, announces that Nubi is his wife and belongs to him, and drags Nubi out of the house while brandishing a whip.

Despite extensive dialogue throughout, The Squall features nondiegetic music for nearly 70 percent of its running time. This high percentage by itself is remarkable, given regular scholarly claims that Hollywood avoided underscoring in this period. But equally striking is the fact that the filmmakers used rerecording to produce this score. Instruction sheets contain a reel-by-reel list of music selections to be placed into the film, and these reel numbers match those in the conductor’s part.6 Only in postproduction would a list based on reels be possible, demonstrating that this music was added during this phase and mixed with the film’s copious dialogue via rerecording. Further attesting to the presence of rerecording, the filmmakers sometimes simply lifted recordings of tunes that had been played during earlier reels and reused them in later sections of the film. Figure 3.1, for example, features a handwritten list of cues for reel 3. Next to cues 4 and 36 (“Gypsy Theme”), the handwritten instructions indicate that these cues need not be recorded but can be merely reused from the sound record for cue 2, which is also “Gypsy Theme.” Far from an occasional tactic, The Squall’s entire score was the product of rerecording.

Like the filmmakers for Lights of New York, The Squall’s filmmakers conceived of the music not as an object to be molded and reworked to fit with specific actions or lines of dialogue but rather as an autonomous entity that should coincide in a segment-by-segment manner. The film features short segments of preexisting classical music associated with Hungary and gypsies, such as Franz Liszt’s Les préludes; Liszt’s Second, Fourth, and Sixth Hungarian Rhapsodies; Antonín Dvorak’s “Tune Thy Strings, Oh Gypsy” and “The Old Mother (Gypsy Song)”; Theodore Moses Tobani’s Second Hungarian Fantasia; and Johannes Brahms’s Hungarian Dance no. 3. Yet while the film’s location and gypsy characters clearly impacted musical selection, these preexisting numbers were not modified to fit the film. Instead of attending to small-scale screen events, The Squall’s filmmakers—as in the late silent era—remained primarily concerned with ensuring that musical cues began and ended at “proper” points.

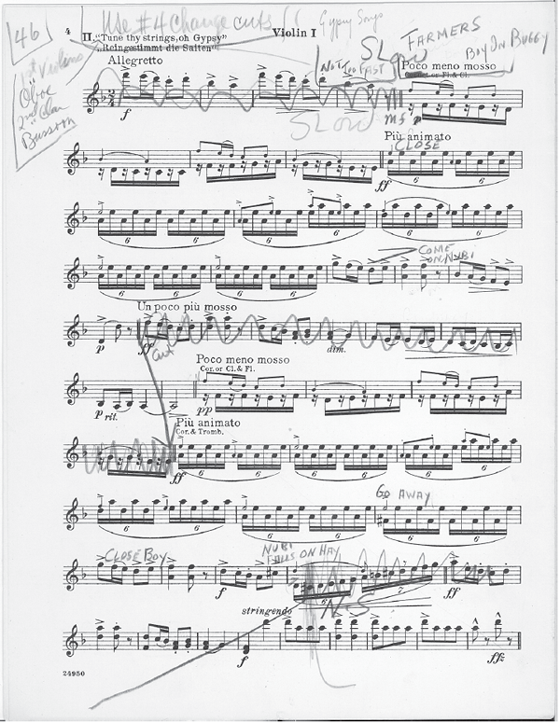

This concern is amply illustrated by the first violin part for cue 46, a thirty-second cue that consists of portions of Dvorak’s “Tune Thy Strings, Oh Gypsy” (“Reingestimmt die Saiten”) (fig. 3.2). The cue begins with the first shot in the scene, which features an extreme long shot of Paul, who is smitten with Nubi, pulling up his buggy next to a haystack. Paul watches jealously as Nubi literally fights off the affections of two farmhands and then jumps into the hay. Just after the end of this musical cue, Nubi walks over to Paul and successfully seduces him. Within this thirty-second cue, seven different penciled markings refer to specific cues from the film. “FARMERS” refers to the workers who are visible in the film’s establishing shot (fig. 3.3); “COME ON NUBI” (spoken as “Come on gypsy” in the film) is spoken by one of the farmers as he attempts to kiss her (fig. 3.4); “GO AWAY” is Nubi’s line as she fends off both farmers; “CLOSE” and “CLOSE ON BOY” (fig. 3.5) both refer to close-range shots of Paul; and “NUBI FALLS ON HAY” (fig. 3.6) refers to her leap into the hay to escape the farmers and attract Paul.

FIGURE 3.1 A list of cues for reel 3 of The Squall.

The Squall music files, Warner Bros. Archives, University of Southern California.

Though the score features numerous penciled markings pertaining to moments in the scene, in general these moments are not precisely synchronized with dialogue or image actions. For instance, in the final version of the film, Nubi’s “Go away!” line occurs two measures before it is listed in the score, and it occurs merely in the middle of the melody. The only penciled marking denoting a salient match between music and action is the final notation reading, “NUBI FALLS ON HAY.” When Nubi leaps in the hay, her landing coincides with the final note of the song, a D played as a short sforzando. Immediately following this note, the score returns to “Gypsy Charmer,” a theme regularly tied to Nubi and her efforts to seduce white men. Timing the end of “Tune Thy Strings, Oh Gypsy” to Nubi’s land in the hay is thus doubly important: it not only matches a physical action, but it triggers the beginning of a narratively appropriate cue. Indeed, the orchestra—having gotten slightly ahead of the image—significantly slows down the final measure to complete the cue as Nubi lands in the hay.

FIGURE 3.2 The first violin part for “Tune Thy Strings, Oh Gypsy,” in The Squall.

The Squall music files, Warner Bros. Archives, University of Southern California.

FIGURE 3.3 “FARMERS” (The Squall).

FIGURE 3.4 “COME ON NUBI” (The Squall).

FIGURE 3.5 “CLOSE ON BOY” (The Squall).

FIGURE 3.6 “NUBI FALLS ON HAY” (The Squall).

Because only the final note of “Tune Thy Strings, Oh Gypsy” requires precise timing with the image, the function of the other penciled markings becomes clear. In this and other scenes throughout The Squall, penciled narrative cues serve primarily as guideposts to ensure that one cue ends and the next cue begins at the proper time. The frequent excisions of musical passages serve as an additional way to enable the cue to end at a precise point in the narrative. For “Tune Thy Strings, Oh Gypsy,” for instance, the filmmakers’ excision of the first four bars and the un poco più mosso section helps the cue reach its conclusion just as Nubi leaps into the hay. Here and throughout the film, The Squall’s score was largely a postproduction amalgamation of preexisting music, kept essentially intact and timed to correspond with the general, large-scale changes in the image. As with The Singing Fool—which also used rerecording—The Squall’s filmmakers seldom used rerecording to achieve precise synchronization between particular actions or lines of dialogue. Instead, The Squall remains heavily indebted to the late silent era, which also favored preexisting music and conceived film music in terms of a series of short, self-contained cues.

Though both The Squall and Lights of New York generally avoid overtly synchronizing music with small-scale actions, The Squall breaks with Lights of New York in its regular use of character-based motifs, a staple of the late silent era. These motifs serve key narrative functions. As we saw in chapter 2, motifs—in addition to helping identify important characters—could also coerce audience members into feeling certain ways about the characters. In The Squall, motifs serve to condemn Nubi’s overt sexuality and her ability to attract men. From a certain perspective, an audience could easily feel sympathy for Nubi. Not only does her flight to the Hungarian family allow her to escape a physically abusive man, but also one might reasonably blame the men on the farm, who pursue the gypsy girl quite aggressively, for the conflicts that ensue. The film, however, places the bulk of the blame for the family’s strife on Nubi’s shoulders. Narratively, she constitutes a disruption to the happy status quo, an agent hellbent on violating “proper” all-white couplings. The film also falls back on the assumption that if a woman turns a man’s head, the woman is at fault for making herself so attractive; the man, in contrast, simply cannot resist his primal urges. Such underlying messages are embedded in the film’s images and narrative trajectory, but they also emerge through the score’s deployment of motifs.

As is typical in the period, the most prevalent theme in the film—a lilting, mysterious, minor-key melody titled “Gypsy Charmer”—is first heard during the opening credits (fig. 3.7). Once the narrative begins, the function of this melody is initially unclear. The theme plays when Nubi seduces Paul, which might cause the audience to assume that this motif constitutes Nubi and Paul’s coupling theme. As the film progresses, however, the same theme is again heard when Nubi seduces Josef and during moments when Nubi, alone in a room, admires herself in the mirror. By this point it is clear that this theme belongs solely to Nubi, and this distinction has repercussions for the film’s attitude toward her. On one hand, when a film grants a romantic love theme to a central couple, this can suggest the film’s tacit endorsement of that pairing by implying that this coupling is somehow “right” through its generation of new, beautiful music on the soundtrack. Attaching a theme to only one character, on the other hand, can indicate self-centeredness and a failure to interact with others in a positive manner. In Don Juan (August 1926), for instance, the score gradually jettisons the motif tied exclusively to Don Juan in favor of a “collective” motif that signifies the romantic union between him and Adriana. The evil, self-absorbed Lucrezia, in contrast, receives her own, separate, unchanging theme throughout the film. In The Squall, centering the score’s theme on only Nubi subtly condemns her selfish, amoral nature long before the family on the farm reaches that conclusion.

While tying a motif to a central character to guide interpretation was hardly an unusual practice in the period, The Squall also more daringly uses silence as a character motif. This “nonmusic motif”—attached to Josef—guides the viewer through the film’s shifting power relationships. Josef’s initial lack of music induces the audience to believe that he is impervious to Nubi’s feminine charms. In contrast to Nubi’s lilting theme, Josef’s musical silence suggests his level-headedness, rationality, and, implicitly, male power. However, linking Josef with silence then helps convey a narrative in which Nubi progressively uses her sex appeal to overcome his resistance. Consider, for example, a scene in which Josef fires Peter and then accuses Nubi of deliberately luring Peter away from Lena. Here the filmmakers are faced with a decision: should they provide “Gypsy Charmer” on the soundtrack (Nubi’s theme) or no music at all (Josef’s “theme”)? The decision to provide “Gypsy Charmer” throughout this long conversation implies that despite Josef’s outward appearance of male authority, Nubi is in fact the underlying possessor of power. Nubi has “hooked” Josef, in spite of his stern admonishments. Further reinforcing this fact, Nubi hums “Gypsy Charmer” after Josef exits, and shortly thereafter we hear Josef himself—the man previously associated with musical silence—humming the catchy “Gypsy Charmer” as well.

FIGURE 3.7 The beginning to “Gypsy Charmer,” Nubi’s theme in The Squall. The film usually presents this theme without words, but at one point Nubi sings the lyrics while admiring herself in the mirror.

The Squall music files, Warner Bros. Archives, University of Southern California (notation modified to better fit the version in the finished film).

This argument between Nubi and Josef ties directly to a scene late in the film in which Nubi overtly seduces Josef, thus implicitly undermining his patriarchal authority. At first, musical silence reigns while Josef speaks sternly to Nubi, suggesting that Josef may have control of the situation. Then, however, the following exchange takes place. Josef accuses Nubi of making advances toward Paul, which causes Nubi to smile. Josef exclaims, “Don’t lie, I can see it in your eyes,” and Nubi responds by saying, “You cannot read these eyes, master. You be blind! Blind!” She rises up and kisses him, and Josef exclaims, “What is that infernal light shining in your eyes?” During this exchange, in which Nubi gains the upper hand via her exotic and sexual allure, the soundtrack moves from silence (Josef’s “motif”) to “Gypsy Charmer” (Nubi’s motif). Nubi, the score indicates, can use her sex appeal to control even the male head of the household. Little wonder, given the overtly patriarchal society of the late 1920s, that the narrative posits such feminine power as dangerous and ultimately needing to be reined in by male authority.

If The Squall shares the late silent era’s tendency to make regular use of themes, it also adopts silent film’s indifference toward diegetically justifying its music by featuring blatantly nondiegetic music from the outset. This, too, differs from Lights of New York, which only gradually allows its music to venture into nondiegetic terrain. But The Squall does avoid presenting diegetic/nondiegetic confusions that might distract the audience. Early in the film, for example, the score stops just before the family hears Nubi scream, which prompts one character to exclaim, “Did you hear that?” Here the filmmakers are apparently aware that playing nondiegetic music during this moment might render the diegetic sound space confusing. The audience might even wonder whether a particular character has somehow detected the score. Determined to prevent diegetic/nondiegetic ambiguities from occurring, the filmmakers coordinate the score to cooperate with the construction of a diegetically understandable sound space.

The Squall’s filmmakers are so concerned with creating a comprehensible diegetic sound space that diegetic and nondiegetic music never occur simultaneously on the soundtrack. During the few instances in which characters whistle or sing songs—such as Peter’s “I’m Unhappy” or Nubi’s various instances of singing or humming “Gypsy Charmer”—the nondiegetic music stops before the song begins and resumes only after the diegetic performance has been completed. The filmmakers plainly did not want the nondiegetic score to complicate the audience’s understanding of the film’s diegetic sound space.

Taken together, Lights of New York and The Squall serve as eye openers to scholars who assume that early 100 percent talking films featured no music. Rather than severing ties with the continuous music practices of the late silent era, certain 100 percent talkies continued to use extensive musical accompaniment. Equally important, both films reveal early efforts to grapple with a key representational conflict: how to negotiate between the late silent era’s continuous music practices and the desire in the early sound era to present a comprehensible diegetic sound space. Of the two, Lights of New York is more musically cautious. Not only do the filmmakers carefully ground music in the diegesis in the early going, but they also remove nondiegetic music at the slightest provocation from the diegesis. The Squall, in contrast, makes no effort to tie its music to image sources. Instead, The Squall’s music halts primarily during moments that depend on the audience’s precise understanding of what constitutes diegetic sound. Though their approaches differ, both Lights of New York and The Squall reveal a growing belief in the period that diegetic/nondiegetic music distinctions were important in the 100 percent talkie. Efforts to retain extensive music in “all-talking” films would be short-lived, however. By late 1929, Hollywood films featured a sudden and substantial reduction in nondiegetic music.

THE REDUCTION OF FILM MUSIC, 1929–1931

Given the plethora of continuous or near continuous music scores in 1928 and early 1929—whether synchronized scores, part-talkies, or a 100 percent talkie like The Squall—few could have predicted that by late 1929, Hollywood would have shifted gears by drastically reducing the amount of music present in nearly all its films. Yet from the fall of 1929 through the spring of 1931, music regularly occupied significantly less than half of a film’s soundtrack. Outside of film musicals, audiences during these years could generally expect to hear relatively short, intermittent musical cues—a far cry from the continuous music regularly provided only a year or two earlier. One of the only exceptions to this tendency is Paramount’s Fighting Caravans (January 1931), a western set during the Civil War that features nonstop music for its eighty-minute running time. Fighting Caravans remains a curious anomaly in a period generally dedicated to the drastic reduction of nondiegetic music.

This shift to sparse accompaniment music was remarkable considering that many of the people in charge of film music from 1929 to 1931 continued to be prominent former silent film music directors and thus had been accustomed to film as a continuous-music medium. Hugo Riesenfeld, the well-known silent film music director and arranger, was hired as music director of United Artists in 1929.7 Erno Rapee, an equally prominent creator of silent film scores, received what was believed to be a record-breaking salary to become the general music director at Warner Bros. in 1930.8 William Axt, the musical director for MGM, had contributed to the scores for two major silent films—Passion (1920) and the 1921 reissue of Birth of a Nation—and had served arranging and conducting duties at the high-profile Capitol Theatre.9 Further attesting to the comprehensiveness of this aesthetic shift, by the end of 1929 all major studios switched from continuous to intermittent music. Viewing the films listed in the appendix from 1926 to 1931 reveals slight differences among studios: MGM conservatively stuck with music and effects-only scores for longer than other studios, while Fox tended to use musical cues a bit more extensively than the others. Overall, however, the substantial reduction of music occurred at all studios.

Yet while studios reduced their amount of film music during this period, they were not in agreement on the terminology used to credit music personnel. The variety of terms in the credits suggests the multiple prior influences on the use of music and how its role in film was understood. From the middle of 1929 to the middle of 1931, by far the most common music credit was for the film’s “score.” But this credit pertains mainly to the continuous or near continuous music scores for films like Warner Bros.’ The Squall or MGM’s The Single Standard (July 1929). Exceptions do exist, such as the score credited to Richard Fall for the intermittent music used in Fox’s Liliom. But typically, studios opted for different terminology to indicate the presence of intermittent music. These options included “background music,” “incidental music,” “music advisor,” “music arrangement,” “music by,” “music composer,” and “music conductor.” Each term suggests slightly different conceptions of film music. “Incidental music,” for instance, draws on theater music terminology, while “music arrangement” suggests a compilation of preexisting music (as opposed to “music composer,” which implies original music).

The most common credit for intermittent music in this period, however, appears to have been “music director” or—in the case of Warner Bros.—“general music director,” a term used by all major studios except MGM. The term music director harks back to the late silent era, when major movie theaters had musical directors who were in charge of music acquisition, cataloguing, and deciding which music to include in the film. The reuse of this term by studios in the early sound era suggests that studios conceived of film music in much the same way: as a process of acquiring, cataloguing, and ultimately placing preexisting music into the film. Indeed, from 1929 to 1931 preexisting music constituted a far larger presence in film scores than original compositions.10 Furthermore, where silent-era music directors shouldered leadership responsibilities that included hiring musicians and organizing rehearsals, the music director in the early sound era was also an overseer. According to music archivist Jeannie Pool, the music director led a team that included composers, songwriters, “orchestrators, arrangers, copyists, conductors, musicians, [and] scorers,” as well as non-silent-era personnel like “cutters, sound engineers, [and] sound effects specialists.”11 Still, this team, as music historians James Buhler, David Neumeyer, and Rob Deemer point out, tended to have an ad hoc rather than a standardized arrangement owing to the rapid aesthetic changes in the early sound era.12

Since music directors led a team of musical staff members, the importance of musical collaboration during this period cannot be underestimated. Pool writes that various composers “wrote and rewrote one another’s compositions; they corrected, edited, and expanded each other’s work, with the goal of making the best music possible in service of the film.”13 Revealingly, when the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences began giving out awards for Best Score in 1934, the award went to the studio music department rather than to individual composers, a practice in keeping with the way scores were produced in the period.14 This tendency toward group authorship makes it risky to assign credit to specific persons, and in this and subsequent chapters I generally assign musical responsibility to the filmmakers as a group rather than to a particular individual.

The sparse, intermittent music style of the period was unlike anything witnessed in the silent era, and thus the shift to this style demands an explanation. To date, scholars have almost uniformly offered what might be termed the “Max Steiner Explanation.” The explanation, advanced by Steiner himself beginning in the late 1930s, provides two reasons for the absence of a film score in the late 1920s and early 1930s.15 First, Steiner writes that rerecording was “unknown at the time,” meaning that the entire orchestra had to be on the set should music be desired. This was not only a big expense but a virtually insurmountable logistical headache as well. Second, Steiner claims that Hollywood’s newfound need to diegetically justify each and every musical cue also resulted in the elimination of nondiegetic music. Steiner’s catchy description of a wandering violinist conveniently providing a love theme has encouraged scholars to argue that an “aesthetics of realism” precluded the use of nondiegetic music in the early sound period.16

Though many scholars have accepted the Max Steiner Explanation, it is nevertheless fraught with misrepresentations, inconsistencies, and inaccuracies. As the remainder of this chapter demonstrates, nondiegetic film music was not eliminated but simply reduced. But even if one overlooks this misrepresentation, one should note that Steiner’s two explanations for the reduction of music contradict each other. The first component of his explanation suggests that filmmakers would have wanted nondiegetic music if the hassles of an on-set orchestra were not so great, while the second component indicates that filmmakers would not have wanted nondiegetic music because it would have created audience confusion about where the music was coming from. Perhaps this paradox reflects filmmakers’ uncertain attitudes toward music during this period, but it paints a confusing and unresolved picture of the early sound era nonetheless. Why would filmmakers have cared about the logistical headache of an off-camera orchestra if their attitude toward nondiegetic music precluded them from wanting such a service in the first place?

Further undermining Steiner’s explanation, I have indicated that rerecording was not only known at the time but was used extensively in Warner Bros. films as early as 1928. Archival evidence reveals that rerecording remained extensive at Warner Bros. at least through 1930, as films like Sally (December 1929) and Golden Dawn (June 1930) relied heavily on the process.17 As I suggested in chapter 2, Warner Bros.’ use of rerecording was probably partly driven by the nature of the studio’s sound-on-disc system, a process that no other major studio adopted. Still, even a cursory look at some of the major films from this period indicates that other studios—including those using sound-on-film rather than Warner Bros.’ sound-on-disc method—also used rerecording. During a ten-minute charity ball scene from United Artists’ Hell’s Angels (May 1930), continuous music plays while depicting dialogue in multiple rooms in the manor, as well as outside on the terrace. During these shifts from one location to another, the music remains unbroken. Recording this music during production would have been a logistical impossibility. Fox’s Seas Beneath (January 1931) similarly features continuous background music that bridges shots featuring dialogue in two different places, thus almost guaranteeing that some form of rerecording was used.

But perhaps the best indication of substantial rerecording at studios other than Warner Bros. comes from two westerns: Fox’s The Big Trail and Paramount’s Fighting Caravans. In both films music repeatedly plays underneath dialogue scenes that are shot outdoors. In many of these dialogue scenes the camera is too close to the moving lips of the characters to make postproduction dubbing a possibility, meaning that dialogue was directly recorded outdoors during filming. Setting up an orchestra on locations like a cliff face, the desert, or a snowy mountainside was a near impossibility, so the music was very likely obtained by recording the music separately and mixing it with the recorded dialogue in postproduction. Even obtaining the music track by playing a phonograph during shooting would not have worked for films like Hell’s Angels, Seas Beneath, The Big Trail, and Fighting Caravans, since the music remains unbroken despite cuts to dialogue in different spaces.

Several scholars have claimed that rerecording was avoided in the early sound period because of the substantial loss in sound quality that resulted.18 Yet if rerecording can be found in a range of early sound films, to what extent did rerecording’s deterioration in sound quality truly prevent filmmakers from using the process? Evidence suggests that the loss of sound quality was sometimes seen as acceptable among filmmakers. In a May 1929 article in Transactions of the Society for Motion Picture Engineers, K. F. Morgan reports on the status of rerecording, stating that sound quality is not significantly impaired even with five rerecordings. Morgan acknowledges that each rerecording “introduces a slight loss in quality” but that some of these issues can be “artificially improved.”19 During the ensuing discussion of the paper, J. I. Crabtree reaffirms, “It is not necessary to sacrifice quality appreciably in the matter of making rerecording.”20 Morgan’s paper would appear to indicate that rerecording, including the placement of music into a dialogue scene, was a regular practice by this point. According to the article, by May 1929 a machine had been developed that automatically rerecorded predetermined portions of sound records. Morgan also offers a description of rerecording for film as well as disc,21 affirming that rerecording was not limited to the sound-on-disc format.

Recently, film historian Lea Jacobs has argued that Morgan’s article was naively optimistic in its claim that rerecording featured a minimal drop in sound quality. Jacobs cites other trade journal articles detailing the technological drawbacks of early sound recording, and she concludes that rerecording entailed a “serious compromise” in sound quality during sound’s early years.22 Film preservationist and historian Robert Gitt, who has listened to Vitaphone discs featuring original sound records and rerecorded sound, concurs with Jacobs’s assessment. Regarding the rerecorded versions, Gitt writes, “Everything—both music and voice—sounds as if it’s coming through layers of cardboard. The primitive playback equipment of the time takes away the treble and takes away the bass, leaving a dull, thin sound.”23

Yet while sound quality may have been reduced, whether this reduction was deemed acceptable by film sound technicians plainly remained an open question in the period. In an endnote to her article, for instance, Jacobs quotes another early sound technician who extols the virtues of rerecording.24 The situation is further complicated by the advent of noiseless recording, which greatly reduced ground noise in both variable density and variable area sound recording. According to Jacobs, ground noise had been a major impediment to rerecording, and the advent of noiseless recording made rerecording more feasible.25 Because noiseless recording appears not to have become widespread until early 1931, it is uncertain whether films like The Big Trail, Fighting Caravans, and Seas Beneath used rerecording as a result of the advent of this new technology. At the very least, however, it is clear that in some cases, the benefits of rerecording outweighed the potential deficits in sound quality.

Steiner’s claim that rerecording was avoided in the early sound era is an overgeneralization. His second claim—that Hollywood felt the need to diegetically justify every cue in the film during this period—also demands reconsideration. To be sure, from 1929 to 1931 Hollywood did increase its efforts to connect music to a diegetic sound source, sometimes straining credibility in the process.26 Still, the notion that Hollywood required every sound to have an image source is an oversimplification. The period’s reduction of music is better understood as part of a broader effort—seen in part-talkies and 100 percent talkies—to construct a comprehensible diegetic sound space, Diegetic comprehensibility could be accomplished in a film featuring nondiegetic music. The Squall, for instance, offers clear demarcations between diegetic and nondiegetic music sections. Consequently, the audience is never induced to question which domain a music cue comes from. Yet reducing nondiegetic music constituted a far easier means for ensuring diegetic clarity, and filmmakers increasingly used this option in 1929 and 1930. Reducing nondiegetic music was not driven primarily by a belief that audience members required diegetic sources for all music (many films did feature nondiegetic or ambiguously located music); rather, reducing nondiegetic music enabled filmmakers to avoid any potential diegetic/nondiegetic confusion.

A second factor—and one ignored in Steiner’s account—surely contributed to the reduction of music: the emerging importance of recording the voice. Initially, when sound recordings served as a substitute for live music performances in the movie theater, little effort was made to record the voice. For instance, in Sunrise (September 1927), when a character shouts to announce that The Wife (Janet Gaynor) survived a dangerous storm, the soundtrack famously provides not the character’s voice, but a French horn that mimics her voice. Several historians have demonstrated, however, that Hollywood increasingly focused its technological efforts on recording the voice during the early sound period. This interest took two forms: obtaining a clear vocal record and showcasing “naturalistic” speech patterns. During the 1930–31 season, for example, quieter recording technologies and directional microphones were both designed primarily to isolate the voice and record it more clearly.27 Moreover, around 1929, Hollywood and its audiences became obsessed with “natural” deliveries, which included accents, “realistic” vernacular, and peculiar deliveries.28 Films from 1929 to 1931 are loaded with such vocal oddities as pronounced accents (Swedish, French, and German accents in particular), street-life or gangster dialects, and stutterers.

The continuous music accompaniment of the silent era directly conflicted with this recorded voice aesthetic. Music, when played at the same time as dialogue, threatened to reduce the audience’s ability to hear and appreciate these odd vocal deliveries. Early microphones, especially those prior to the 1930–31 season, were “weak in sensitivity, fidelity, dynamic range, and directionality,”29 thus increasing the likelihood that the inclusion of a competing sound element like music might interfere with dialogue. Consequently, filmmakers probably faced pressure to eliminate music for the sake of showcasing the voice. Revealingly, even Fox’s The Big Trail, which contains an unusually large amount of music for the period, almost universally eliminates all music when the three characters with the most unusual vocal deliveries—a comical Swede (El Brendel); the gravelly voiced Red Flack (Tyrone Power Sr.); and a man named Windy (Russ Powell), who imitates sounds such as coyotes and Indians—deliver their lines.30 Interest in the voice may also explain the reduction of what constituted typical music volume level: when music is played during moments of dialogue in films from late 1929 to 1931, it is generally at a substantially lower level than prior part-talkies and early 100 percent talkies.

The reduction of music, however, caused a new set of problems. In the silent era, film music had served a range of useful purposes: it signified the prestige of the film, heightened anticipation for the feature, identified and instantly characterized important characters, underlined emotion, and even served song-plugging functions. Reducing film music meant that these important narrative functions might have to be abandoned. To address this problem, Hollywood employed tactics that minimized diegetic/nondiegetic confusion while still allowing film music to serve some of its prior uses. These tactics can be seen as tentative solutions to the representational conflict between late silent film accompaniment and sound film’s emerging expectations for its sound space.

These solutions were not universal, and filmmakers used music in quite diverse ways. Still, the following four sections provide what no scholar has yet offered: an outline of general music strategies from 1929 to 1931. Nearly all films used music during the opening and closing title sequences to guide the audience in particular ways. A number of films also employed what I term “diegetic withdrawal”: a situation in which a film initially uses only diegetic music before gradually introducing ambiguous or downright nondiegetic music cues. Films also regularly featured scenes that were set in locations where music was plausible or likely, and this diegetic music sometimes guided audience attention and interpretation in a manner nearly identical to nondiegetic music. Finally, Hollywood continued to use the theme song as a method of guiding the audience through the narrative.

Opening and Closing Title Sequences

From 1929 to 1931, films almost always feature music during the opening and closing titles, even if they contain no other nondiegetic music. In many cases the tunes that play during the opening credits also play at the end of the film. For films featuring a theme song, the presentation of the song during both the beginning and end title sequences was a must, but other films also contain similar or identical tunes at the beginning and end. For example, United Artists’ Abraham Lincoln (August 1930) provides a medley of patriotic American music over the opening and closing titles; Hell’s Angels features the second movement from Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony during the opening credits, intermission, closing credits, and subsequent blank screen; and Seas Beneath offers military marches during the beginning and end title sequences.

Title sequence music served a range of purposes. For more expensive films, classical music could elevate the film’s prestige. Hell’s Angels, for instance, had the highest budget in film history up to that point, a fact that was heavily publicized.31 It received a much-hyped premiere at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in Hollywood, and newsreels in the period emphasized the colossal number of prestigious film personnel who attended, including Gloria Swanson, Cecil B. DeMille, Dolores Del Rio, Charles Farrell, and Buster Keaton. Musically, the film used the second movement from Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony to announce itself as a prestigious film. Tchaikovsky’s music was a frequent source for orchestral overtures during the silent era, and silent-era overtures often strove to raise the prestige of the moviegoing experience.32 Not surprisingly, the musical arranger for Hell’s Angels was Hugo Riesenfeld, a veteran of late silent film accompaniment practices.

Opening credit music could also suggest genre, thus immediately coaxing the audience to respond to the film in a particular way. Though a single tune could accomplish this purpose, many films used two contrasting themes to foreshadow the nature of the film, a strategy that would become conventional practice by the late 1930s.33 The opening title sequence for RKO’s Lonely Wives (February 1931), for instance, begins at a very fast, or presto, tempo with the xylophone featured as a prominent instrument, followed by a far slower and more romantic piece featuring strings. This opening predicts the nature of the film: it is a zany comedy (the first theme) with some romance (the second theme). Similarly, Fox’s They Had to See Paris (September 1929)—a fish-out-of-water story about an Oklahoma family that travels to Paris to hobnob with the upper class—begins with a Gershwinesque tune (representing the sophistication of the city) followed by faster-paced, rousing band music (presumably representing good ol’ smalltown American life).

A particularly clear example of how opening title music could indicate the central appeals and themes of the film occurs in the three-themed opening to Party Girl (January 1930), a B film produced by Personality Pictures. Party Girl ostensibly tells a cautionary tale about how companies exploit sexually attractive young women by using them to sell their products. However, in a mixed-message tactic typical of Hollywood, the film contradicts its own public service message by regularly titillating the audience via images of scantily clad women and overt reminders that naked women are just off the frame’s edge. The opening credits’ music suggests these contradictory messages by beginning with a perky jazz theme titled “Oh! How I Adore You,” written for the film by Harry Stoddard and Marcy Klauber. As we saw in chapter 1, jazz during this period had connotations of drinking, dancing, and sexual promiscuity. Lest the audience get the wrong idea about the film’s appeals, however, a “foreword” appears after the opening credits that condemns the party girl system. The disclaimer begins with the sentence, “Sex in business—the ‘Party Girl’ racket—threatens to corrupt the morals of thousands of young girls who seek to earn their living decently,” and the music underscores the seriousness of this message by shifting from jazz to a dramatic, minor-key classical music passage. After more text bemoaning “the shameful effects of this practice,” the film reveals its supposed public service agenda: “It is our earnest hope that this film may arouse you and other public-spirited citizens to forcibly eliminate the vicious ‘Party Girl’ system.” Though the timing is a bit off, triumphant brass-heavy music roughly coincides with this inspirational line. The three music styles during the opening suggest three ways to read the film: as sexual titillation, as an illustration of a tragic social practice, and as a call to action.

If opening credit music could assist the audience by foreshadowing some aspect of the film, closing music offered a guiding hand by regularly dipping into the last few seconds of the narrative to provide a final statement. On occasion this spillage lasts more than a few seconds. Abraham Lincoln—a film that otherwise contains music that can be read diegetically—allows nondiegetic music to slide into the last minute and a half of the narrative to convey a final take-home message. The filmmakers use songs like “When Johnny Comes Marching Home,” “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” “The Star-Spangled Banner,” and “My Country ’Tis of Thee,” combined with images of the log cabin where Lincoln was born and the Lincoln Memorial, to suggest that Lincoln attained immortality in the eyes of Americans by sacrificing his own life in the pursuit of the larger goal of preserving the Union. Because immortality is a transcendental, nonmaterial concept, the filmmakers likely felt justified in deploying nondiegetic music, which itself seems to exceed the physical confines of the diegesis. Though not strictly “part” of the narrative, opening and closing music raised expectations and guided audiences toward particular interpretations.

Diegetic Withdrawal

First used in Lights of New York, what I call “diegetic withdrawal” was one of the most common methods for incorporating nondiegetic music into a film in the early sound era. Diegetic withdrawal refers to a situation in which a film begins with clearly marked diegetic music, only to drift toward music that is either ambiguous or downright nondiegetic in the later sections of the film. This ambiguous music often enables the film to reflect a character’s emotions and guide audience response. The drift from diegetic to nondiegetic terrain is usually quite difficult for the spectator to detect, thus resulting in music that seemingly emerges organically from the diegesis rather than emanating from an external, nondiegetic narrational force.

Scholars have noted film music’s potential to slide between diegetic and nondiegetic boundaries and even blur those distinctions,34 yet it has not been pointed out that many filmmakers systematically exploited this film music potential in the early sound era. In Paramount’s The Wild Party (March 1929), Clara Bow’s first talkie, the first few musical cues are located firmly within the diegesis. Duke Ellington’s “Jig Walk” accompanies a college girl dance party, and Scott Joplin’s “Maple Leaf Rag” plays during a scene in a seedy saloon. In neither case does the film present an actual image of diegetic performers, but based on the match between musical selections, instrumentation, and location, the urge to tie these songs to the diegesis is a strong one. “Jig Walk” was a popular dance tune in the 1920s and is thus appropriate at a college dance party, while “Maple Leaf Rag” sold many sheet music and piano roll copies.

As the film progresses, however, several cues become impossible to justify diegetically. After providing dance numbers inside a house party, for example, the filmmakers cut to the beach outside the house, where two characters share a romantic moment to a ukulele-based rendition of the Buddy DeSylva, Lew Brown, and Ray Henderson tune “The Song I Love.” The presence of prior diegetic music makes the audience less likely to notice the fact that there is no justification for this exterior music. Similarly, two later moments in the film—when the lead character, Stella (Clara Bow), spends a romantic evening with her professor (Fredric March) and later when she tearfully packs her things in preparation to leave college—receive diegetically unjustifiable music cues. Both are clearly in keeping with the emotional tone of the scene: the former tune is a largo (slow tempo), string-oriented version of—once again—the romantic “The Song I Love,” while the latter tune is a minor-key rendition of “Wild Party Girl,” the film’s theme song. Thanks to the use of music that is clearly diegetic early in the film, however, the nondiegetic status of these cues is not particularly noticeable.

Film historian Donald Crafton argues that, beginning in mid-1929, the industry moved toward a more subdued use of sound, a tactic that by mid-1930 meant unostentatious sound that receded into the narrative.35 Diegetic withdrawal, with its emphasis on music that nearly always seemed to emerge from the narrative world, was part of this movement. Even when music drifted into nondiegetic territory, it often retained close ties to the narrative rather than serving as a source of attention in its own right. United Artists’ Alibi (April 1929), for instance, uses diegetic withdrawal to convey character emotion and guide audience allegiances. The first two-thirds of Alibi present diegetic renditions of many jazz tunes, including “I’ve Never Seen a Smile like Yours,” which United Artists exploited as a theme song.36 These contemporary jazz tunes take place in a nightclub and a theater, two locations where audiences would expect to hear music. But during an extended and emotionally intense scene in a back room of the nightclub, the music slowly eases into potentially nondiegetic territory. During this scene Danny (Regis Toomey), an undercover police informant, enters the room, unaware that the gangsters in that room have discovered his connection with the police. After the gangster Chick Williams (Chester Morris) fatally shoots Danny and flees, the police officers arrive and hold Danny in their arms until he dies.

This scene is pivotal to the narrative. Thanks to the suppression of key information, the audience remains uncertain whether Chick is a law-abiding man for much of the film. His cold-blooded murder of the likable and brave Danny resolutely and permanently directs the audience’s ire and disgust directly at Chick and suggests that the audience respect and admire the heroic efforts of police to bring gangsters like him to justice. Moreover, Danny’s death justifies the film’s final scene, in which a police officer and personal friend of his pretends to shoot the panicstricken Chick, thus demonstrating Chick’s cowardice. In short, the heightened emotions of this scene dictate the audience’s loyalty and drive the remainder of the narrative.

The filmmakers use music with an increasingly tenuous tie to the diegesis to help communicate the scene’s tension and shift the audience’s alliance toward Danny and away from Chick. Diegetic withdrawal begins when Danny enters the room and shuts the door. On the soundtrack frenetic jazz from the nightclub is heard. Though such music would seem to qualify as diegetic, in all previous scenes music is rendered inaudible the moment that this door shuts. Violating the film’s own sonic rules, this loud and salient music increases in volume when the door is shut, and continues during striking close-ups of Danny and the mobsters. Here, then, music has shifted functions: where it once operated as what David Neumeyer terms “disengaged” background music (meaning music that displays no awareness of the narrative action), it has now violated the film’s own sonic logic to convey the intensity and extreme danger that Danny suddenly faces.37 In this way the “neutral” music up to this point has subtly become a narrational force that urges the audience to align itself with Danny and sympathize with his plight.

After Chick mortally wounds Danny, the music aligns the viewer more firmly with Danny by veering even farther into ambiguous territory. As Danny lies dying in the arms of the police, the soundtrack unexpectedly supplies Hawaiian ukulele music. Danny, near death, exclaims, “Listen! Pretty!” Is this music coming from the nightclub? All of the nightclub’s other music has consisted of contemporary jazz tunes, and the ukulele music thus seems a poor fit with the diegesis. Perhaps the tune is subjective sound—music that the dying Danny hears inside his head before going to heaven? The smile on Danny’s face as he dies supports this interpretation—for countless films in this period, death is a painless process tantamount to peacefully falling asleep—and surely also suggests that Danny will go to “paradise” upon his death. If this odd music can be recuperated diegetically, however, the scene’s final cue cannot. When Danny dies, the soundtrack shifts to a choir, a decision that accentuates Danny’s noble self-sacrifice. Bit by bit, film music in this and many other films in the period subtly shifts from “realistic” background music to music that reflects interior states and guides audience response.

When film music from the period drifts toward nondiegetic territory, it most commonly underscores moments of heightened emotion. In Party Girl the one instance of music that has only a tenuous tie to the diegetic world occurs when Ellen (Jeanette Loff) sits down and bemoans the fact that her former fiancé, Jay (Douglas Fairbanks Jr.), has married someone else. As a series of superimpositions on the image track encapsulates Jay and Ellen’s past romance, a vocal rendition of the song “Farewell” is heard on the soundtrack—a song with no clear source in the image. Similarly, Little Caesar’s (January 1931) only ambiguous musical cue occurs when Tony (William Collier Jr.), a gangster who has lost his nerve, returns to his mother. As Italian music plays from no obvious source, Tony and his mother talk about how he used to be a “good boy” and “sang in the choir,” and the two wind up hugging and crying. Again, a diegetically tenuous music cue in Warner Bros.’ Other Men’s Women (January 1931) occurs during a dance hall scene in which Bill (Grant Withers), the main character, gloomily remembers Lily (Mary Astor), the woman he loves but cannot have. This recollection coincides with a change of music to Joseph Burke’s “The Kiss Waltz,” a song that had previously been associated with their romance. Though this could be read as a change in dance numbers, the image shows couples continuing to dance in the background, and the instrumentation and volume level differ markedly from the prior song. In these instances—as well as many others from the period—diegetic withdrawal allows the film to present what seems to be an exclusively diegetic sound space while simultaneously allowing music to aid in the presentation of emotionally laden moments.

In the early sound era, then, many films systematically shifted from diegetic to nondiegetic music during the course of the story. Diegetic withdrawal thus reveals a newfound awareness of diegetic/nondiegetic distinctions that was not generally evident in late silent and early synchronized films. However, because diegetic withdrawal features a gradual shift to the nondiegetic realm, the early sound era features a copious amount of ambiguously located music. This ambiguity encourages the film music analyst to consider what, precisely, qualifies as diegetic or nondiegetic music. Film music cannot be identified as diegetic or nondiegetic based on sound alone—it is the interaction between sound and image that dictates how an audience will categorize the music. The preceding examples suggest that diegetic and nondiegetic categorizations are best thought of in terms of a range of factors: Does the provided music seem likely to be diegetic given the setting and character actions (such as dancing) onscreen? Does the musical instrumentation match any onscreen musician(s) that might be imaged? Do volume and reverberation levels change based on the camera’s distance from a possible sound source? Since these questions often do not result in answers that fit entirely within strict diegetic or nondiegetic categories, films from this period demonstrate the importance of thinking in terms of a diegetic/nondiegetic spectrum rather than an either/or categorization.38

Location-Based Music

From 1929 to 1931 Hollywood regularly justified the presence of music by featuring it in diegetically plausible locations. Like diegetic withdrawal, location-based music hides the fact that an external narrative force guides the selection and application of music. Diegetic music is not the main focus of this study, but in the early sound period it—like nondiegetic or ambiguously located music—sometimes played an equally important role in guiding audience response and interpretation. If one wishes to obtain a full understanding of the trajectory of the early sound film score, diegetic music also needs to be considered.

Rather quickly, filmmakers established locations in which music was deemed appropriate, and they frequently reused these locations. Nightclubs regularly feature jazz music (Alibi); dance halls contain dance/jazz music (Other Men’s Women); parties at upper-class mansions feature string-oriented orchestral or chamber music (Hell’s Angels, They Had to See Paris); scenes set in smaller houses or apartments contain phonograph or radio music (Other Men’s Women, Little Caesar); and bars/saloons often feature piano roll music (The Wild Party).

In location-based instances of music, its attentiveness to the narrative varies widely. At one end of the spectrum is a “realist” film like RKO’s Millie (February 1931), with cabaret music that demonstrates neither awareness of nor consideration for narrative events. Volume levels remain constant regardless of dialogue levels, and major narrative shifts—such as Millie’s (Helen Twelvetrees) sudden realization that her husband has a secret girlfriend—are not accompanied by any change in the cabaret performance number. Instead, the songs exist within their own realm, offering complete performances in the background regardless of narrative events.

In other films, however, the music’s volume is “conveniently” raised, lowered, or kept steady in ways that assist the narrative. Most often, this occurs during romantic portions of the film. In Hell’s Angels, diegetic orchestral music accompanies a ball. When characters move outside for a romantic interlude, the music’s volume does not lower, as one might expect, but remains constant—the better to provide lush music that matches the romantic moment in the narrative. A more salient adjustment of volume to express a scene’s romantic tone occurs in Other Men’s Women. During a scene in which Bill professes his love to already-married Lily, the phonograph plays “The Kiss Waltz.” When dialogue occurs, the music’s volume level decreases substantially, while during moments of silence—which include embraces and kissing—this romantic tune is allowed to swell to a much louder volume, thus reflecting the passion that the couple feels. Through this tactic, the dialogue remains entirely intelligible while the music still plays a vital role in expressing the passionate mood of the scene. Both Hell’s Angels and Other Men’s Women offer a way to feature a “realist” aesthetic of diegetic music while simultaneously utilizing music’s affective potential.

On occasion, films even link the subject matter of the diegetic song to a romantic scenario. For example, RKO’s Check and Double Check (October 1930)—the heavily promoted and financially lucrative film adaptation of the Amos ’n’ Andy radio show39—features only diegetic music outside of the opening and closing titles. The film still uses music, however, to overtly comment on the narrative. An instance of this occurs when the film cuts from a house party performance by Duke Ellington and his Cotton Club Orchestra of the love song “Three Little Words” to a scene exterior to the party in which the in-love couple, Richard (Charles Morton) and Jean (Sue Carol), row down a river outside the house and then sit on a bench. After some romantic exchanges, Richard says to Jean, “Listen! Do you hear what they’re singing? That seems to say it so much better than I can.” Though the music remains entirely diegetic, it has changed functions from a “realistic” backdrop to something that “coincidentally” comments on the narrative. This use of music is nearly identical to how the theme song’s lyrics in the early synchronized film comment on the narrative. The difference is that by this 1930 film, such a song is more likely to contain a diegetic pretext for its presence.

The Persistence of the Theme Song

Given the sparse musical aesthetic of 1929 to 1931, one might assume that the theme song—so prevalent during the synchronized score period—would have disappeared. Yet the theme song offered such profitability in terms of ancillary sales that filmmakers refused to abandon it entirely. Unlike theme songs from 1927 to early 1929, however, theme songs from mid-1929 to 1931 were far more likely to contain a diegetic justification. For example, though Millie features very little music, the filmmakers still find an extraordinary number of opportunities to plug the eponymous theme song, several of which take place within the diegesis. A melodramatic instrumental version of the tune accompanies the opening credits. Bouncier “soft jazz” versions occur when Millie first visits a cabaret (the music stops at one point and then resumes with the same song), during a second cabaret scene in which the words to “Millie” are revealed (the song here is presented three different times within the same extended scene), as nondiegetic underscore for love interest Tommy (Robert Ames), during an intertitle that indicates the passing of time, during a third cabaret scene, and throughout the closing credits. Similarly, “Wild Party Girl”—the theme song to The Wild Party—is heard not only during the opening and closing credits but also as a diegetic vocal performance and as a nondiegetic minor-key instrumental version that accentuates a sorrowful moment late in the film.

The increased need to link the theme song with a diegetic source might on the surface appear to be quite limiting, but Fox’s Up the River (October 1930) demonstrates that limitations can in fact foster creativity. Up the River, despite being a prison film, still manages to incessantly plug “Prison ‘College’ Song,” a tune written by Joseph McCarthy and James F. Hanley. To justify the tune’s many diegetic renditions, the filmmakers treat it as the prison equivalent of a college alma mater song. Inmates of the fictional Bensonatta prison perform the song regularly throughout the film, know the tune by heart, and sometimes even remove their caps to sing the tune. Its identity as an alma mater song helps justify its performance during moments such as the beginning and end of a variety show run by the inmates and a baseball game against an opposing prison. If such measures to plug a theme song seem absurd, this approach is nevertheless consistent with the way the film depicts Bensonatta jail in general. Like college, Bensonatta is a place where residents chat amiably with the staff, put on theater productions, root for the sports team, and leave and return to the premises seemingly at will. Seeing a song-plugging opportunity in this humorous take on jail life, the filmmakers were able to justify the repeated presence of the theme song within the broader world of incarceration.

The above examples demonstrate the continued importance of music from 1929 to 1931, even for films that did not feature musical numbers as central attractions. Nondiegetic music did play an important role for many films from this period, but tactics like diegetic withdrawal tended to draw attention away from music’s nondiegetic identity. Far from being a period that entirely abandoned nondiegetic music, the years from 1929 to 1931 contained numerous explorations into the ways in which diegetic, ambiguously located, and fully nondiegetic music could be deployed to serve narrative ends.

From a modern perspective, one might expect the period’s sparse approach to film music to be restrictive to filmmakers. The perceived need to venture into nondiegetic territory in piecemeal fashion, combined with intermittent rather than continuous music, would seem to result in limited opportunities to employ music to mark characters, reflect themes, or convey affect. But while diegetic withdrawal and a sparse music aesthetic may have rendered certain music functions more difficult, it simultaneously opened other options for filmmakers in this period. Two films in particular, Liliom and The Big Trail, deserve attention for their efforts to capitalize on advantages offered by a relatively small amount of music. As is the case with many films made from 1929 to 1931, neither film has received attention from film music scholars.

LILIOM AND THE SPARSE MUSIC AESTHETIC

A major advantage of sparse music is that those moments that do contain music become infused with a heightened level of significance. Richard Fall’s relatively sparse score for Liliom helps articulate the enduring potential of true love, directs attention toward the film’s use of movement as a metaphor for a character’s purpose in life, and above all reflects love’s potential to transcend the difficulties and banalities of physical reality—a central theme for Frank Borzage, the film’s director.

Based on the 1909 play by Ferenc Molnár, Liliom tells a story that has since become more familiar to moviegoers through Fritz Lang’s 1935 adaptation of the same play and especially through the Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein musical Carousel (1956). Liliom (Charles Farrell) is a carousel barker in Budapest whose life is going nowhere. He is handsome but uneducated and is known primarily for his womanizing lifestyle. Julie (Rose Hobart) is a simple working-class girl who falls in love with Liliom and is willing to sacrifice everything for him. Though the match seems an odd one, Liliom is struck by Julie’s faith in him, and the couple marries. When Julie becomes pregnant, Liliom—crippled by fears that he cannot provide for his family—is induced by his friend “The Buzzard” (Lee Tracy) to commit robbery. The plan goes awry, and Liliom kills himself rather than allowing himself to be caught by the police. In the supernatural world the Chief Magistrate (H. B. Warner) offers Liliom a chance to return to earth ten years later and set things right with his family. Liliom returns and speaks with his daughter without introducing himself, but he quickly loses his temper and slaps her. Incredibly, when his daughter describes to Julie how she was slapped in the face, this reminds Julie fondly of Liliom. Liliom’s return to earth is thus ultimately a success, since it has reminded his wife of her happy memories of Liliom.

Musically, Liliom restricts its cues mainly to motifs that articulate the nature and strength of Liliom and Julie’s love. Through this restriction the film suggests that the couple’s love drives the narrative events and explains their behaviors and reactions. In accordance with the period’s typical practice of diegetic withdrawal, the film first uses explicitly diegetic music to tie certain themes to the couple’s love. For instance, when Liliom and Julie share an intimate moment on the carousel ride, carousel music plays while Liliom wraps his arms around Julie and leans her outward into space. Liliom then hops on the tiger that she is riding, and Liliom and Julie stare intently into each other’s eyes. Through these intimate gestures the filmmakers suggest a link between Liliom and Julie’s attraction for each other and the carousel music heard on the soundtrack. During these moments the filmmakers eliminate all other sounds of the fair other than the carousel music, which helps tie carousel music even more closely to the couple’s love.