CHAPTER 8

The Industry Behind the Addiction

Wisconsin Avenue. It’s a good address for a group taking on the cheese industry.

In their offices at the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine’s headquarters in Washington, DC, Mark Kennedy and Mindy Kursban were combing through government records like bloodhounds tracking a criminal. The Physicians Committee is the organization I founded in 1985 to promote better nutrition, better health, and better research. Mindy and Mark are attorneys. Mindy was educated at Emory University, Mark at Washington and Lee.

Using the Freedom of Information Act, they had unearthed a stack of contracts between the government and fast-food chains to push cheese, grants to researchers aiming to make dairy products look healthy, and advertising schemes aimed at boosting cheese sales. In this chapter, I’ll share what they found. If you imagined that food industry giants have your best interests at heart, you will find some new things to think about.

Triggering Cheese Craving

Exhibit A: The Cheese Forum.

Among the documents these legal sleuths uncovered was a presentation, dated December 5, 2000, at what was called a “Cheese Forum.” Dick Cooper, the vice president of cheese marketing for Dairy Management Inc., was about to unveil a new plan to boost cheese sales across America. He took to the podium. “What do we want our marketing program to do?” he asked the audience of industry execs.

“Hmmm. Good question,” the audience was no doubt thinking. “How are we going to promote cheese? Ask convenience stores to put cheese displays near the registers? Find a celebrity to pose with a wheel of Cheddar? Give away samples on street corners?”

No, those are small-time ideas. The cheese industry is far more creative than that. And Dick Cooper gave the answer: “Trigger the cheese craving.” The idea was not to make cheese sound tasty or to show how practical it can be in a sandwich. The plan was to work inside consumers’ heads—and get America hooked.

Cooper made his case. Customers can be divided into two categories, he said. “Enhancers” are people who sprinkle a little mozzarella on a salad or grind some Parmesan on pasta. Forget them; they are not worth targeting. The group to go after was labeled “cravers”—people who open the refrigerator door, break off a chunk of cheese, and stuff it in their mouths as is. Cravers love cheese, and, with a little prompting, they will double or triple their cheese intake.

So, how do you trigger food cravings? Just ask anyone who ever smelled fresh popcorn walking into a movie theater, anyone who ever walked past a bakery, or any baseball fan who ever smelled stadium hot dogs. If you were in these situations, you weren’t necessarily thinking about these foods at first, but all of a sudden they leapt into your world and you had to have them. So, industry’s trick is to use suggestions—subtle or not—that bring the product to mind as often as possible, and then make sure that the product is widely available so that your craving leads to a purchase. Cravings can be triggered, and people aiming to push food products know it.

What was most surprising was that this marketing program—designed to fuel food addiction—was not launched by Kraft, Sargento, or the cheese makers of Normandy. It was a program of the U.S. government.

Your Government at Work

Here’s how it works: The U.S. government collects money from dairy producers and hands it over to an outfit called Dairy Management Inc. (DMI). Right now, the amount totals about $140 million a year, and DMI uses it to push cheese and other dairy products.

DMI’s story actually starts a century ago. In 1915, a foot-and-mouth disease outbreak threatened the image of the dairy industry, and the National Dairy Council was formed for damage control. Over the years, industry programs promoting milk and other dairy products have grown, and in 1983, the government took on a new role for the industry. The Dairy and Tobacco Adjustment Act created a federal board for dairy promotions, and eventually the government consolidated these programs under DMI.

You might be asking why the government is involved in cheese marketing at all. After all, it doesn’t provide marketing services for shoes, computers, make-up, or plumbing supplies. Why cheese? The answer has nothing to do with health. It has to do with money and politics.

As we’ve seen, DMI’s plan was, in essence, to make cheese inescapable—the equivalent of having popcorn not just in theaters, but just about everywhere. But how to do that? If you guessed “blow cheesy smells through air vents,” “ask the president to wear a cheese hat during the State of the Union address,” or “change the song lyrics from ‘amber waves of grain’ to ‘ample waves of Colby and American process cheese spread,’” you’d be wrong. DMI realized that the way to reach into every city and town in America was through fast-food chains. A single corporate decision can affect what tens of millions of people eat every day.

So DMI contracted with Wendy’s to push a Cheddar-Lover’s Bacon Cheeseburger. During the promotional period, Wendy’s sold 2.25 million pounds of cheese. DMI worked with Subway to market Chicken Cordon Bleu and Honey Pepper Melt sandwiches. It contracted with Pizza Hut to unveil the Ultimate Cheese Pizza with an entire pound of cheese in a single serving. DMI worked with Burger King, Taco Bell, and all the other fast-food chains to trigger cheese craving in the same way that movies, bakeries, and baseball parks—intentionally or not—promote cravings of their own.

Under contract with DMI, the chains put more cheese items on the menu, put cheese slogans on the cashiers’ hats, and did their best to make customers choose cheese instead of salad. You might not have been thinking about cheese when you walked through the restaurant door, but DMI aimed to make it inescapable. It’s everywhere.

What!? The government is intentionally promoting cheese craving? The same government that is supposedly interested in our health—it’s trying to make us crave cheese? You bet. No matter how fattening and cholesterol-laden cheese may be, by law, the government has to promote it, thanks to the relentless lobbying of the powerful dairy industry that led to the creation of a broad range of federal dairy-promotion programs. And it has worked. Cheese sales have climbed year after year.

At a meeting in Phoenix in 2013, DMI CEO Tom Gallagher listed the program’s successes.1 Since 2009, DMI’s pizza partnerships had turned ten billion extra pounds of milk into cheese for pizza. DMI provided staff to McDonald’s headquarters to build the company’s expertise and sales. Gallagher projected that its partnership with Taco Bell alone would sell the cheese equivalent of 1.7 billion pounds of milk in 2013, and two billion more in 2014. And the program worked overseas, too. Contracts with Domino’s, Pizza Hut, and Papa John’s moved more than 100 million pounds of cheese in Pacific Rim countries.

Propping Up Sales

If it surprises you that the cheese industry has managed to insinuate its way into the government, this is just the beginning. The industry-government partnership also has a special way of targeting children. When cheese prices fall, the government buys cheese to boost farm income. Similarly, when beef prices fall, the government buys beef. Suddenly, children in schools find more cheeseburgers in their lunch lines. In fiscal year 2015, the government’s Agricultural Marketing Service bought more than 160 million pounds of cheese, at a cost of nearly $300 million.

As I drafted this chapter, I checked the menu for the District of Columbia Public Schools. And, yes, cheese was all over it. There was pizza, “hand crafted in our kitchen on whole grain crusts.” There was a Steak and Cheese Sub, a Cheese and Yogurt Platter, a Toasted Two Cheese Sandwich, and cheeseburgers. And just in case kids had not had enough cheese already, they would find shredded Cheddar at the salad bar.

So, does this mean that all the while that Michelle Obama was campaigning against childhood obesity, the USDA was working to push cheese sales? That is exactly what it means, and I don’t need to tell you who won. The government programs that push cheese were there long before Mrs. Obama’s Let’s Move campaign was launched and, if nothing changes, will be there well into the future.

Money and Politics

This does not mean the food industry is indifferent to health. Quite the opposite. The industry is keenly interested in health—or, more specifically, what you believe to be healthy.

Every five years, the U.S. government revises the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. These guidelines are the blueprint for all nutrition programs in the U.S., and a model for many other countries, as well. The revision is led by a committee appointed by the USDA and the Department of Health and Human Services.

The committee hearings are a spectacle to behold. The committee members take their seats on a stage in a large auditorium. In front of them, a microphone is plugged in, and one by one, speakers step up to make a three-minute pitch. Representatives from the National Dairy Council, the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, the Sugar Association, the Salt Institute, the Chocolate Council, the liquor industry, and everyone else with something to sell tell the committee members why their products should be part of the American diet. The committee then weighs the testimony and whatever other evidence it can gather and issues its report.

As the guidelines were being revised for the year 2000, Mindy Kursban noticed something peculiar. Digging into the résumés of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee members, she found that one had been given a $42,000 grant from DMI, along with fellowships from Kraft, the maker of Velveeta and other cheese products. Another committee member had received a half-million-dollar grant from a company making dairy-based products. A third had received grant payments from the National Dairy Promotion and Research Board and the National Live Stock and Meat Board. The committee chair had been a paid consultant with the National Dairy Council and Dannon—the yogurt company—and had also been paid more than $10,000 by Nestlé Switzerland, a maker of ice cream and other milk products. Of the eleven committee members, six had financial ties to the dairy, meat, or egg industry.

Financial ties are not necessarily off limits for government panels. After all, if the Pentagon is buying new aircraft, it might want advice from Boeing, Lockheed Martin, Embraer, and whomever else might have detailed knowledge and something to say. But if most of the panel members were from one manufacturer, it would obviously not be good. So the government has a law—called the Federal Advisory Committee Act—that requires balance, and bars inappropriate special interest influence.

So, on behalf of the Physicians Committee, Mindy filed suit in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia. We did not have the funding, legal staff, or clout that industry and government have. But it helps when you are right. On September 30, 2000, U.S. District Judge James Robertson laid down his decision. We won our case. The government had violated the law, he ruled, and had to clean up its act.

Ever since, the process has gotten better. Yes, the food industry reps still stand up to the microphone every five years to plead their case to the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, and they work behind the scenes to influence committee members. But the government panel is more careful than in the past, and industries are finding it harder and harder to fight the mountain of research showing the risks of meat and dairy products and the value of truly healthful foods.

Truth and Advertising

On May 3, 2007, the U.S. government did something it practically never does. It stood up to the dairy industry.

Two years earlier, Mindy and Mark had gone to the Federal Trade Commission with dairy advertisements in hand. The dairy industry was making an extraordinary claim, that dairy products promote weight loss.

“Wow!” you might be thinking. “That’s a good one. Milk fattens calves, and now it is going to make me slim!”

The notion came from Dr. Michael Zemel, a researcher at the University of Tennessee. Dr. Zemel conducted experiments in mice, which, he said, showed that boosting calcium intake could accelerate weight loss. He then reported the same result in people. Overweight individuals who cut calories seemed to lose more weight when dairy products were part of their low-calorie diets, compared with just cutting calories alone.

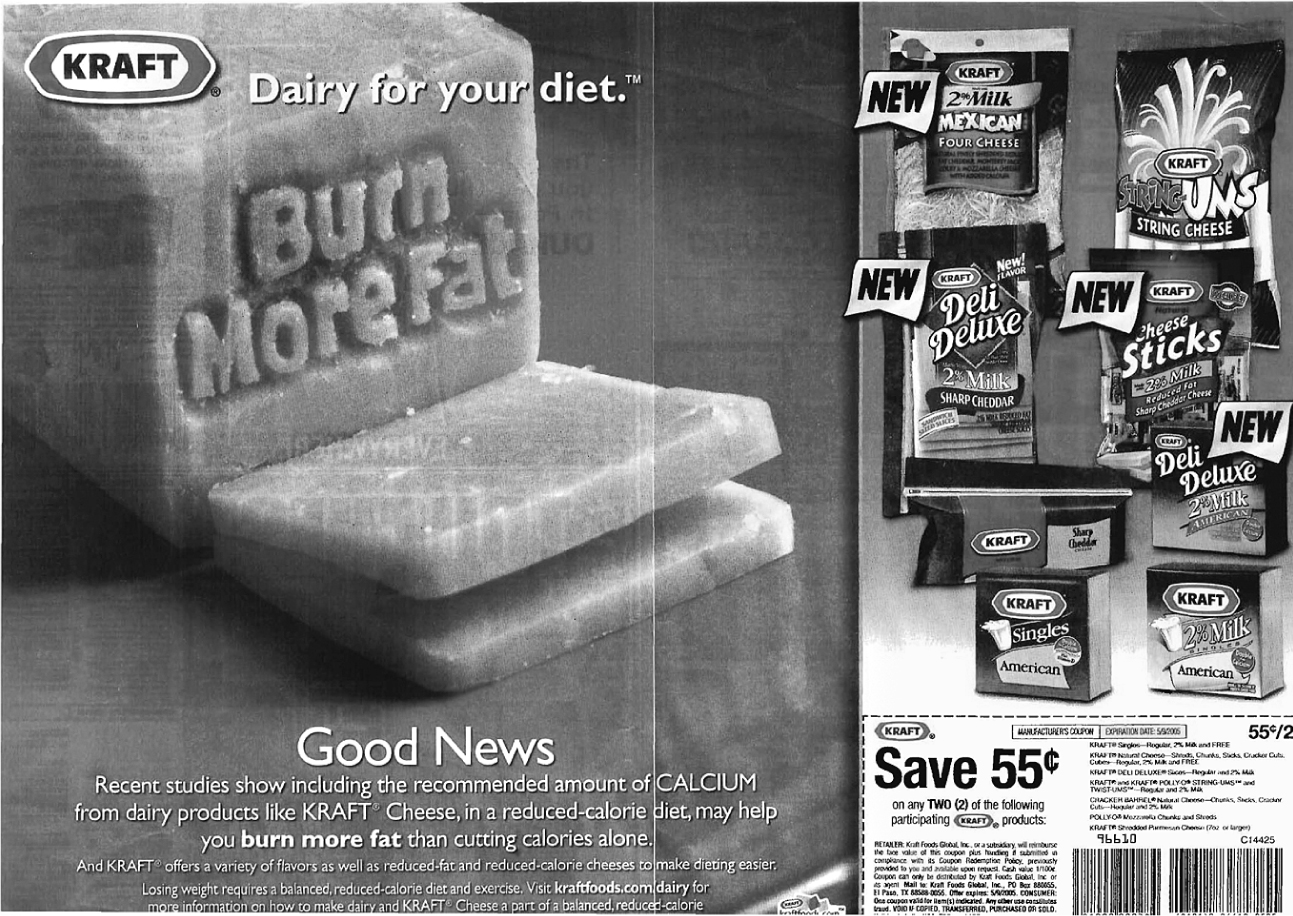

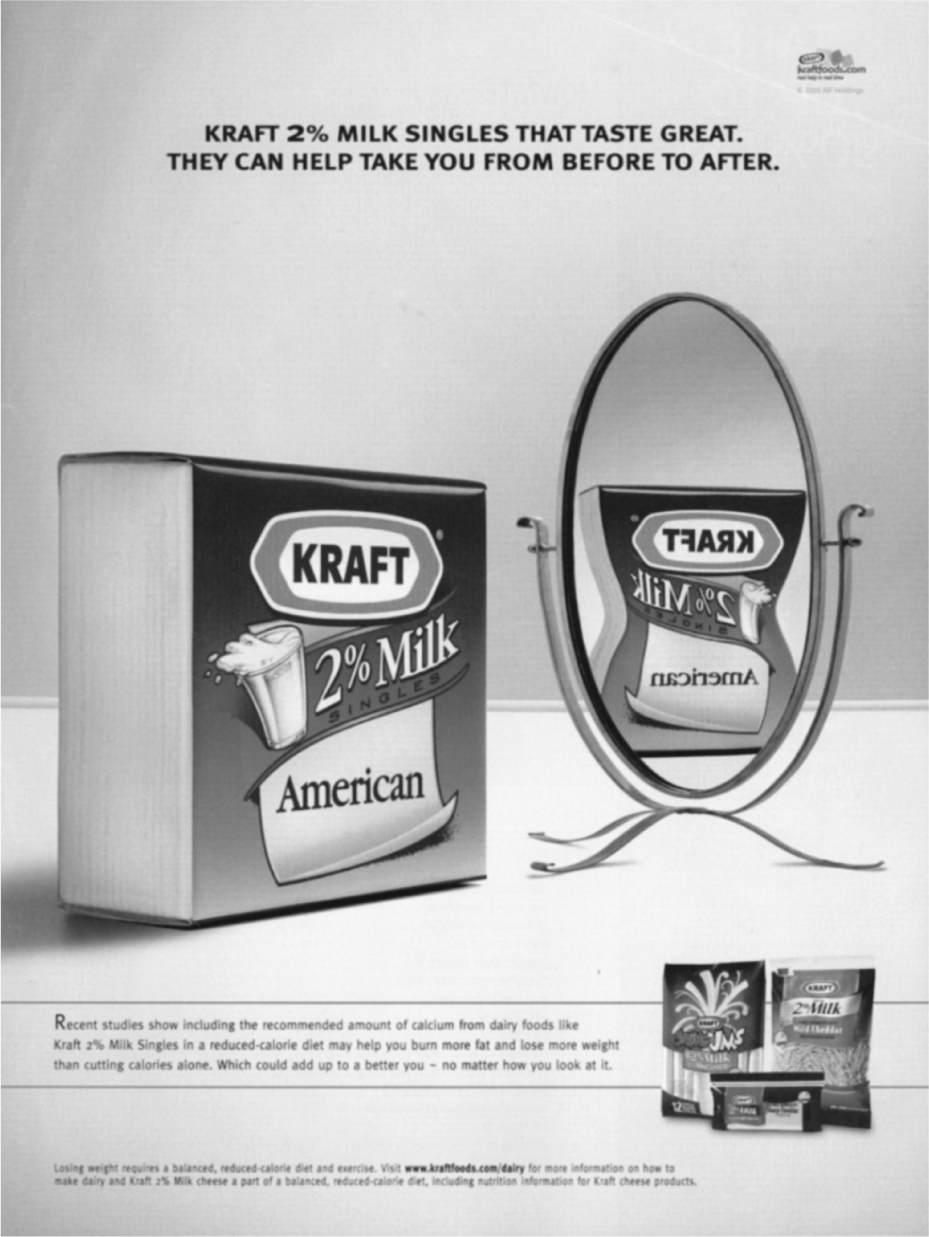

Based on his research, the dairy industry advertising machinery started humming. An ad from Kraft showed a sweaty block of cheese emblazoned with the words “Burn More Fat.” The ad copy said, “Good News. Recent studies show including the recommended amount of CALCIUM from dairy products like KRAFT Cheese, in a reduced-calorie diet, may help you burn more fat than cutting calories alone.” Another, for Kraft Singles, made the same claim. Dr. Phil McGraw appeared in a dairy ad, sporting a milk mustache, with the title “Get real. About losing weight.” Milk, cheese, calcium—yes, they are going to slim you right down. The weight-loss claim was trumpeted in People magazine, Good Morning America, and endless other outlets.

But a closer look showed problems. In Dr. Zemel’s 2004 article in the journal Obesity Research,2 he disclosed that his research had been paid for by the National Dairy Council. And the study was small—ten people in a control group, and eleven each in a high-calcium and a high-dairy group. Another Zemel study, reaching the same conclusion the following year, was funded by General Mills and was similarly small.3 Moreover, it turned out that Zemel had patented his dairy–weight loss plan, and had a book to sell, too. It all smelled like money, not science.

Most problematic was that other researchers had been unable to replicate his findings. Researchers from the University of British Columbia had compiled the data in a review published in the Journal of Nutrition. Nine studies had looked at experiments to see the effect of dairy products on body weight. None showed any benefit.4 Drink all the milk you want, they found—it will not help you lose weight.

Our lawyers went to work. First, we asked the Federal Trade Commission to investigate. And to its credit, it did. In the meantime, Kraft’s sweaty cheese block had to go. We filed suit against the company, calling on it to stop claiming that cheese or any other dairy product would cause weight loss. Kraft quickly let us know that it would not run the ads any further. And two years later, the Federal Trade Commission pulled the plug on the dairy–weight loss claims altogether.

In the aftermath, our team took one more look at the evidence. And indeed, it does not support any notion that dairy products help you lose weight. We eventually found forty-nine research studies testing the effect of dairy products or of calcium alone, with or without calorie-cutting, and found that the notion that dairy products promote weight loss is clearly a myth.5 As we saw in Chapter 2, cheese can easily do the opposite. It helps you pack on the pounds.

So, What about All Those Other Claims?

The dairy–weight loss controversy showed a troubling side of the industry. It was dishonest. It was surprisingly eager to make health claims that did not even pass the sniff test. If the weight-loss claim is not real, it makes you wonder, what about all those other claims, like “milk builds strong bones”? That notion has been embedded in our memories since our grade school days and is right up there with Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny in popularity. Could that be on shaky scientific ground, too? Or what about the idea that older women should drink milk to protect against bone breaks? That is a common idea, but what does the science look like?

At Penn State University, researchers launched the Penn State Young Women’s Health Study, including eighty adolescent girls who participated for ten years, from age twelve to twenty-two.6 The researchers followed their diets and exercise patterns. Along the way, they carefully examined their bone strength and integrity.

Their calcium intake covered a wide range. Some got as little as 500 milligrams per day, while others got much more—as much as 1,900 milligrams a day. But it turned out that it did not matter. Variations in calcium intake from milk, cheese, or anything else did not affect their bones. Milk did not make their bones stronger, more resilient, or less likely to break. What did matter was exercise. Those children who exercised more had better bone integrity.

It turns out that, although the body does need some calcium, it does not need an especially large amount of it. The government has been pushing calcium—as much as 1,300 milligrams per day for teenagers. But studies show that, once you are getting about 600 milligrams per day, there is no benefit from going higher. Also, calcium does not have to come from dairy products. It is found in a wide range of much more healthful foods. Beans and green vegetables are at the top of the list (and deserve a big place in everyone’s diet), and many other foods contain calcium, too. In addition, dairy products don’t “build strong bones.” So long as growing children are getting good nutrition, those who skip dairy products have just as good bone development as other kids.7

At the other end of the age spectrum, older women—especially older white women—are often told that, because they are at risk for osteoporosis and hip fracture, they should drink milk. The idea is that milk’s calcium will shore up their bone strength. Harvard University researchers put the notion to the test in the Nurses’ Health Study. Following 72,337 women over an eighteen-year period, the study found that those who drank milk every day had no protection at all from hip fractures.8

Well, maybe the women who weren’t drinking milk were taking calcium pills, and so milk’s benefits were harder to see in the comparison. But that was not the case either. Zeroing in on women who never used calcium supplements, those who drank at least a glass and a half of milk daily actually had slightly more bone breaks than those who avoided milk—about 10 percent more. The added fracture risk could have been due to chance, but it was clear that milk was not helping at all.

But maybe old age is too late. Maybe what counts is how much milk you drink when you’re young, so you build up your bone strength. That’s the idea the dairy industry has pushed. So the Harvard team looked at that, too. It turned out that, among women, milk consumption during adolescence had no effect at all on women’s hip fracture risk in older age. The researchers also looked at men. In a large group of men participating in the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study, there was an effect of milk, but it was exactly the opposite of what milk producers would have wanted. Milk-drinking during the teenage years was associated with more—not fewer—bone breaks in later life. Every additional glass of milk consumed per day during adolescence was associated with a 9 percent increase in hip fractures in later life.9

None of this means that you do not need calcium. You do. But you do not need enormous amounts of it, and you don’t need calcium from milk at all. The “milk builds strong bones” idea has been promoted for commercial reasons and has been memorized by parents and children over the generations. But, like the “milk causes weight loss” claim, it is a myth.

Personally, I have found it disturbing that some of the nutritional lessons that have been pounded into our heads since childhood—and that we have accepted as fact—are nothing more than industry marketing schemes. It is also disturbing that the industry is still actively promoting shaky ideas in schools and on television in order to push its products. These notions endure, and they displace helpful information about what really can strengthen bones and promote good health. There is another striking dairy claim that comes from a company in Hagerstown, Maryland. The company makes chocolate milk that is advertised as a sports recovery drink under the name Fifth Quarter Fresh.10 The University of Maryland tested the product in high school football players.

The lead investigator, Jae Kun Shim, reported stunning results on the University of Maryland website.11 Kids who drank Fifth Quarter Fresh did better in cognitive tests. In other words, they were mentally sharper, and that was true, even if they had suffered football-related concussions. The university website posted pictures of the magic drink and an endorsement from Clayton Wilcox, superintendent of Washington County Public Schools: “There is nothing more important than protecting our student-athletes. Now that we understand the findings of this study, we are determined to provide Fifth Quarter Fresh to all of our athletes.”

However, there is another side to this story, as you have no doubt guessed. The research was paid for through a $100,000 financial arrangement between the dairy company, the university, and the Maryland Industrial Partnerships Program.

As of this writing, the results have not been peer-reviewed or published. However, the university did release a PowerPoint summary of the results, including composite scores for verbal memory, visual memory, processing speed, reaction time, and other measures. As it turns out, none showed any benefit of the milk product that met the usually accepted criterion for statistical significance. In other words, either the product was useless or any benefits observed on one test or another could have been due to random chance.

The notion that athletes should drink chocolate milk has been heavily promoted by the USDA’s milk marketing programs, which push chocolate milk at marathons and in paid advertisements featuring athletes posing with chocolate milk containers. So far, there is no sign they are letting up.

Buying Friends

Sometimes, the dairy industry dispenses with trying to convince people of its merits and just buys loyalty with cash.

Take the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, for example. Founded as the American Dietetic Association, it changed its name to “AND” in 2012. The organization oversees who can and cannot be a registered dietitian, and, in some states, only registered dietitians and very few other professionals are legally allowed to give nutrition counseling. If you’re a cheese manufacturer, you would love to have dietitians on your side. They are the ones who give nutrition advice, go on news programs, oversee hospital food services, and do lots of other things that could help or hurt your business.

AND’s website includes a page called “Meet Our Sponsors.” At the top of the list is the academy’s national sponsor, the National Dairy Council. The next level down names its premier sponsor: Abbott Nutrition, which sells dairy-based baby formulas and supplements, such as Ensure.12

What? The organization representing America’s dietitians is bankrolled by the dairy industry? Actually, the money has piled up pretty fast. AND’s 2015 financial report lists $1.2 million in sponsorship contributions, plus $2.1 million in grants and $1.8 million in corporate contributions and sponsorships to the AND Foundation.13

AND is not alone. The National Dairy Council pays $10,000 a year to be part of the American Heart Association’s Industry Nutrition Advisory Panel. Along with other panel members—Nestlé, Coca-Cola, the Egg Nutrition Center, the Beef Checkoff Program, and a handful of other food industry giants—the National Dairy Council is granted special access to AHA’s Nutrition Committee—the group that sets AHA policies and weighs in on federal nutrition issues.

The American Academy of Pediatrics is active in nutrition, too, providing guidance on what parents should feed their children. Corporate sponsors are invited to contribute to the AAP’s charitable fund. The list includes Dannon, Coca-Cola, and plenty of pharmaceutical manufacturers.14

A decade ago, DMI cooked a deal with the American Dietetic Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the National Medical Association to launch the 3-A-Day program. The idea was that three servings of dairy products daily is the way to fight the “calcium crisis”—which DMI also invented.15

These health organizations are well aware that food companies that send them checks are doing so with the sole aim of influencing their nutrition policies: They hope that dietitians will recommend milk instead of green vegetables for calcium, that heart doctors will overlook the load of saturated fat and cholesterol in cheese, and that pediatricians will not worry too much about pudgy pizza-eating children. So these health organizations do maintain policies about conflicts of interest. AND specifically reports, “The Academy’s programs, leadership, decisions, policies and positions are not influenced by sponsors.” It is fair to say that the sponsors do not believe that and many AND members do not either. A group of dietitians, called Dietitians for Professional Integrity, holds that the country’s largest nutrition organization should not be sponsored by food industry giants.16

My impression is that industry funding has indeed had a corrupting influence on major health organizations. It continues only because it is so common and longstanding that otherwise good scientists, doctors, and dietitians have simply gotten used to it.

Keeping You in the Dark

Slanted and even dishonest messages, ill-founded advertisements, and buying friends—what else does the food industry do? Two more things that you should know about:

Don’t call it cheese. When you buy a wheel from Miyoko’s Kitchen—a manufacturer of the creative cashew-based cheeses we will meet in the next chapter—you’ll notice that the word “cheese” is nowhere on the package. Ditto for products from Kite Hill and similar producers of nondairy cheeses. That’s because in California, the word “cheese” cannot legally be used unless the product is made from dairy milk. The industry hopes that consumers will be less likely to go for a “cultured nut product.”

Ag-gag is real. Let’s say an undercover investigator finds that cows injected with bovine growth hormone have mastitis—an infected udder—and that milk from a sick cow, along with antibiotics used to treat the condition, might have been sent to a dairy anyway. What if an investigator finds disease-ridden animals or evidence of cruelty on a farm and has video footage to prove it? The agriculture lobby has been working hard to ensure that, if police are called in such an instance, it will be the journalist who is arrested.

In 2013, Amy Meyer was prosecuted under a Utah law for videotaping at Dale T Smith and Sons Meat Packing Company in Draper City, Utah. Amy had seen a cow who appeared to be sick or injured and was being taken away with a tractor, like garbage. She took out her phone and started recording. The manager came out and told her to stop, but Amy refused. Soon, the police arrived. The company was owned by the town mayor, Darrell Smith, and the plan was not to help the cow or clean up the slaughter operation. The plan was to stop any documentation of what went on inside.

The charges against Amy were eventually dropped. But the agriculture lobby continues to push for “ag-gag” laws because it knows the public would be repulsed by the disgusting—and sometimes illegal—activities that go on in these facilities.

Industry Is Alive and Well, Even If You Are Not

The dairy industry is still working hard to keep you hooked and believing the health mythology that it creates. It is busily cooking deals with fast-food chains, buying friends among health experts and health organizations, and lobbying to keep its products prominent in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. When cheese prices fall, the government still buys it and puts it into schools, regardless of children’s real nutritional needs or health challenges. The money the industry has at its disposal has been more than sufficient to dissolve scientific integrity and ethical principles among many organizations that should know better.

But, like Mark and Mindy, a growing number of attorneys, advocates, and health experts have been moved by the health problems, environmental disasters, and animal welfare issues caused by industry and are working hard to expose them. And when members of the public become aware of these problems, there is not enough money in DMI’s marketing budget to make them forget.