Figure S2. Isidor Kaufmann (1853–1921), Portrait of a Rabbi (also known as Portrait of a Young Hasid), oil on panel, 15 × 11.5 cm. Courtesy of Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Gift of Oscar Singer through the British Friends of the Art Museums of Israel, 1952, 2065. Photo © Tel Aviv Museum of Art by Dima Valershtein.

SECTION 2

Golden Age: The Nineteenth Century

David Assaf, Gadi Sagiv, and Marcin Wodziński

INTRODUCTION: TOWARD THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

THE PROLIFERATION OF HASIDISM in the years shortly before and mainly after the death of the Maggid of Mezritsh in 1772 demonstrates how a movement that had no central authority and no formal mechanisms of organization could nevertheless develop with enormous vitality. The very lack of a rigid ideology allowed for a great variety in the forms of leadership, governing ethos, and types of practice. This flexibility gave the movement greater strength, as it attracted different types of leaders and followers. Some of the leaders cultivated elitism, while others were more populist. Some focused on the material needs of their Hasidim, while others stressed the spiritual. But whether in Ukraine, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Galicia, or Central Poland, by the beginning of the nineteenth century one central characteristic was shared in common: the structure of the court with a tsaddik at its center surrounded by his Hasidim. In the space of a few short decades, a movement thus took shape and was poised to expand itself still further in the next century.

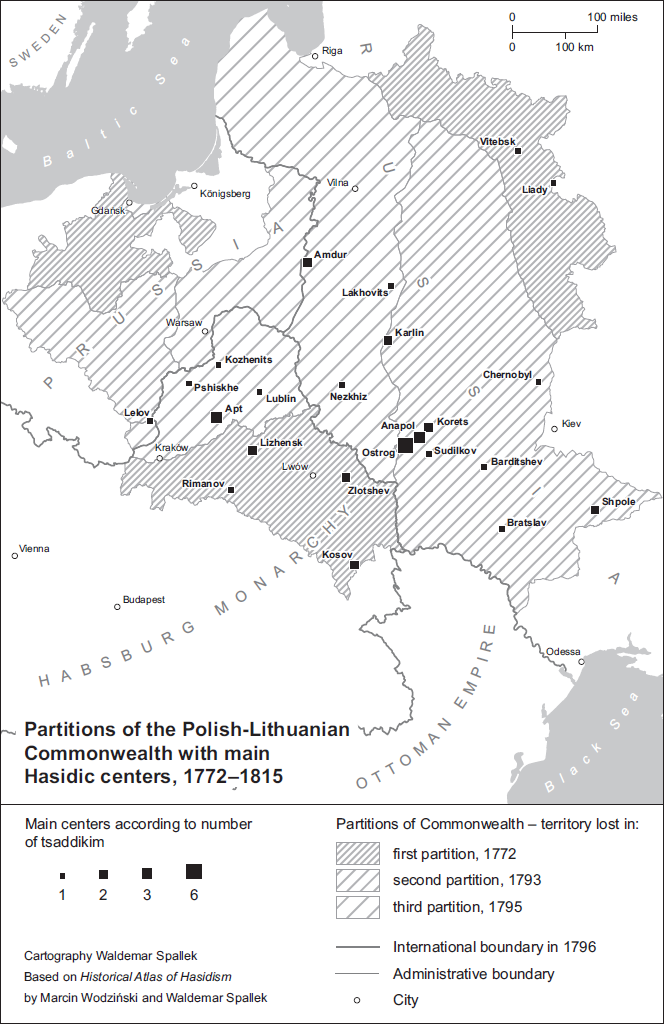

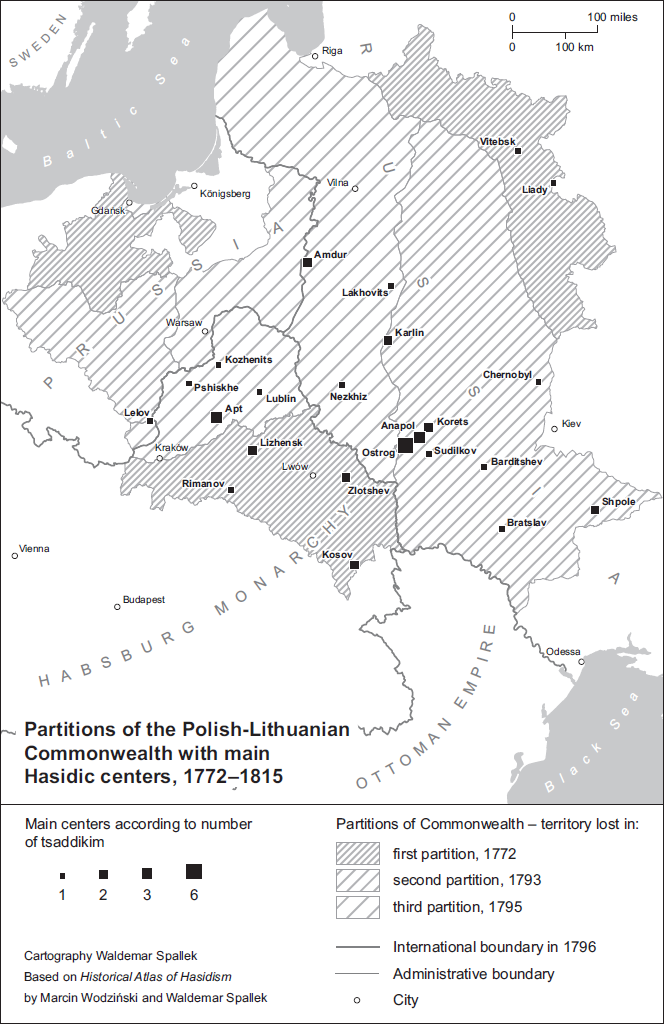

By the end of the eighteenth century, the Jews of Poland no longer lived in the commonwealth that had been their home since the Middle Ages—and in which Hasidism first arose. The three partitions of the commonwealth left the Jews in four political units: Prussia, the Habsburg Empire, Russia, and the area of Central Poland under Russian rule, but with a certain degree of autonomy (see map S2.1). After the first partition in 1772, there still was a sizable Jewish community in the part of Poland not swallowed by its neighbors. Prussia absorbed approximately twenty thousand Jews in the first partition. Starting with Frederick the Great in 1750, the Prussian state departed from medieval tradition by intervening actively in the internal affairs of the Jewish community in order to try to integrate Jews into society. As a consequence of this integrationist policy, Polish Prussia was not fertile soil for Hasidism, whose western penetration stopped more or less at the border with Prussia.

The first partition most affected the Jews of what became known as Galicia—that is, roughly the southern tier of today’s Poland together with the westernmost quarter of today’s Ukraine. This area contained approximately a quarter of a million Jews. They joined the Habsburg Empire, which already had a small Jewish community and a Jewish policy that still largely followed traditional lines: limited Jewish autonomy within the framework of various occupational and social restrictions. However, as we shall see in greater detail in chapter 19, starting in the 1780s, the Habsburg government began a policy of tolerance that both improved the legal status of Jews and encouraged adoption of German culture. As Hasidism entrenched itself in this region, it had to contend with forces of modernization that took much longer to develop to the east.

Map S2.1. Partitions of Poland

Russia, which at first annexed territories with only thirty to forty thousand Jews, had been officially closed to Jewish settlement and had no organized Jewish community prior to the first partition. By the third partition, however, Russia had gained a total of approximately 600,000 Jews, the largest Jewish community in the world at that time. Jewish policy there oscillated between continuing to treat the Jews as an autonomous ethno-religious community and trying to force them to integrate and lose their Jewish identity.

Indeed, the Jewish policy of all the regimes that absorbed the Jews from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth vacillated between favoring Jewish modernizers, on the one hand, and preference for traditional, conservative Jews, on the other. At times, this latter policy could prove instrumental in supporting Hasidim in their battles with Maskilim and other modernizers.

By 1815, when the Congress of Vienna stabilized the borders of Eastern Europe, the stage was set for the development of Hasidism in the different countries, each with its own political constellation. Although the borders remained relatively easy to cross and Hasidism developed along roughly common lines throughout the region, the new political order left its stamp on the proliferation of courts and their character in the long nineteenth century.

Between 1815 and World War I, Hasidism enjoyed a Golden Age. It was in this period that the small, elitist, and mystical circles of the eighteenth century coalesced into a genuine mass movement. To be sure, the development from circle to court and from court to movement that we have traced in the eighteenth century was already on a trajectory to win a major following for Hasidism. But as vigorous as the movement was by the end of the eighteenth century, it was qualitatively and quantitatively transformed in the nineteenth. Almost everything one associates with classic forms of Hasidism came to maturity in that century: courts with all their rituals and cultural expressions, the tsaddikim and their various forms of leadership, different types of dynastic inheritance, the diversification of Hasidic ethos and teaching, extension of geographical boundaries, new genres of Hasidic literature, and new modes of political engagement.

Despite relatively recent scholarship on the nineteenth century, Simon Dubnow’s judgment that Hasidism went into decline from its eighteenth-century age of creativity still shapes perceptions of the history of the movement. While the relatively small number of sources for the eighteenth century has been extensively mined, historians have only begun to explore the much richer materials available for the nineteenth century: internal Hasidic literature, the polemical and journalistic writings of Maskilim, and governmental archives from Russia, Poland, and the Habsburg Empire. Many subjects, such as the migration of Hasidim to the cities at the end of the century, their responses to modern political upheavals, and the history of specific courts remain terra incognita. Indeed, this paucity of research continues into the crucial interwar period as well.

One defining characteristic of nineteenth-century Hasidism was demographic. Never before had it achieved such rapid increase in followers, most won over by conversion rather than natural growth. While rapid growth also characterized Hasidism after World War II, in our period, Hasidic courts won the loyalty of a larger proportion of the overall Jewish population of Eastern Europe. This Golden Age was therefore, in part, a story of numbers. In addition, the geography of Hasidism expanded dramatically, moving from its birthplace in Podolia and other eastern provinces of what was originally the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in a westward direction toward Galicia and Central Poland, as well as Hungary and Romania. Indeed, we will show in chapter 10 that these new territories became even more numerous with tsaddikim and their followers than were the original heartlands of Hasidism.

As a result of Hasidism’s centrifugal explosion into most regions of Jewish Eastern Europe, it developed varieties of religious and social expressions. It will prove convenient to divide these varieties geographically (Russia, Poland, Galicia, and Hungary), but, even though these different political settings surely influenced the development of Hasidism in each, we want to be careful not to stamp these different regions with rigid and unchanging definitions. While there is some truth to generalizations about the Hasidism of different regions, they conceal counter-examples that belie the “essential” character of Hasidism in this or that place.

With the geographic and demographic expansion of Hasidism, the average Hasid often lived far from the court of his tsaddik. As a consequence, the courts developed into highly significant institutions as the vehicles for keeping a dispersed group of followers unified. The so-called regal courts in particular boasted expansive physical structures and retinues of functionaries and servants. A pilgrimage to the court took on a strongly ritual flavor. At the same time, most of a Hasid’s life took place in the shtetl, the small market towns in which most Hasidim—and most Jews—lived and, within the shtetl, in the shtibl, the local prayer room of the Hasidic branch. This section of our book therefore contains a detailed description of how Hasidim lived when they did not attend the court, how they struggled for power and influence within their local communities, what was the role of women, and, finally how the Hasidim related to non-Hasidic Jews and non-Jews as well.

If the focus here is primarily on social history, the history of Hasidic ideas is no less important. As opposed to section 1 of this book, here we do not have a separate chapter on Hasidic ethos or rituals, in part because the movement now developed so much variety that it is hard to make generalizations. In the chapters on varieties of Hasidism in Russia, Poland, Galicia, and Hungary, we examine a range of religious themes as they found expression in the different dynasties. A particular avenue for disseminating these ideas was in the book culture that developed in the course of the nineteenth century, including a wave of new books of tales of tsaddikim starting in the 1860s. However, the development of Hasidic ideas did not take place in a vacuum. The growth of the Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment) in Eastern Europe paralleled the growth of nineteenth-century Hasidism. Some of the Maskilim made Hasidism the target of their parodies and polemics, but the story we will tell of relations between these two opposing groups will be more complicated, including Maskilim who were sympathetic to Hasidism and local relations of Hasidim and Maskilim that confound ideological enmity.

Finally, our story includes relations between Hasidism and the state. While the Maskilim sought to mobilize the state against the Hasidim, these efforts generally proved futile since the states in which the Hasidim lived refused to outlaw Hasidism as a “sect.” At the same time, Russia, Congress Poland, and the Habsburg Empire all had an interest in modernizing and acculturating the Jews that led to conflicts with Hasidim and the emergence of a Hasidic politics directed toward these states.

These momentous events of the nineteenth century had a profound effect on Hasidism. From an element of radical ferment in the eighteenth century, Hasidism evolved into a bulwark against modernity, a force of conservatism. By the end of the century, the rise of Zionism and other forms of secular Jewish politics mobilized the Hasidim further to combat what they saw as threats to their way of life. Indeed, Hasidism as we know it today owes much to its transformation into perhaps the representative of tradition in the rapidly modernizing world of the nineteenth century. And yet—as we argued in the introduction to this book—Hasidism was itself a product and a form of modernity, both as a movement of opposition to the secular world and as a religious and social phenomenon never seen before in Jewish history. The tradition that Hasidism fought so hard to defend against the assaults of the modern world was itself ironically an innovation.