The otherwise cheerful musical film Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, starring Dick Van Dyke as a mildly dotty Caractacus Potts, takes a dark turn about halfway through. The two Potts children find themselves holed up in a barony where children are outlawed, and whose baron employs a “child catcher” with a spectacularly long and bulbous-tipped nose who can smell out children. In no time at all he sniffs the guileless kids out, then lures them with candy into his candy-wagon-slash-cage. In retrospect, it is no surprise to learn that this film script was written by Roald Dahl.

Dahl wrote preposterous noses. Of one of the eponymous, child-hating subjects in The Witches: “She can actually smell out a child who is standing on the other side of the street on a pitch-black night.” When a child protests that he is reasonably clean (having recently bathed), he learns, “It isn’t the dirt that the witch is smelling. It is you. The smell that drives a witch mad actually comes right out of your own skin. It comes oozing out of your skin in waves, and these waves—stink-waves, the witches call them—go floating through the air and hit the witch right smack in her nostrils.”I

Detection dogs (known in various dogly circles as sniffer dogs, detector dogs, or working dogs) detect much more than disease, of course. Just how much more has not yet been discovered. Until recently, we assumed that the dog’s nose was only as good as our imagination was in applying the nose to finding things. Our imagination has proven more fertile of late—hence the expansion from training dogs to find drugs and land mines to orienting dogs toward mealybugs, smuggled agricultural products, and endangered ribbon snakes. Dogs have been trained to find minute amounts of environmental contaminants: derivatives of gasoline production and various toxic products at industrial disposal and waste sites. They work sniffing out sea cucumbers being illegally exported from the Galápagos, and the smuggled ivory and horns unfairly removed from their elephant and rhinoceros hosts.

And dogs detect us: tracking, trailing, search-and-rescue, and scent-identification dogs pursue the missing, escaping, lost, or dead; the criminal, confused, unseen, or unlucky. Their noses’ authority is acknowledged by our legal system: no less than the U.S. Supreme Court described the detector dog’s sniff as “sui generis,” a tool unlike any other. Tracking’s earliest appearance among canids was no doubt as hunting: predators like canids cannot just wait until prey shows up under their claws or leaps into their open mouths. Being able to follow the tracks of (hoped for) prey is a necessary adaptation. Since the time of their wild ancestry, domesticated dogs have modified the hunt into a hunt-minus-consumption. Pliny wrote of huntsmen carrying even their aged and infirm hunting dogs with them, so good were they at finding their quarry by “snuffing with their muzzles at the wind.” But in common with those hungry wolves, the dogs find us primarily through one thing: our stink-waves.

The smell of a person is so strong that dogs can follow it over time, underwater, after the person is long gone, and even after the thing the person touched has actually blown up. In one study, researchers found trained bloodhounds able to identify who had touched a pipe bomb—after the pipe bomb exploded. The person’s scent, laid on the pipe by touching it while setting it up, “survived” when little of the actual pipe did. Dogs have been trained to find drowned persons: the odor of decomposition rises to the surface of a lake or other still body of water; some dogs can even track in flowing stream or river water. Where sonar, divers, and underwater cameras fail, a dog may start pointing at the location from the dock, and then from a boat narrow the search space to just twenty feet across. Cadaver dog handler Cat Warren writes that when a dog alerts during an underwater search, it is “like stepping from one room to another”: from fumbling in the dark to a room aglow. Avalanche-rescue dogs have found people buried under twenty-four feet of snow: the person’s scent travels to the surface and the dog, after some digging to convince himself, alerts there.

In some cases of search and rescue and trailing, the dog is given an article of clothing to “search out”; but in most tracking, all the dog needs is to know that he is after some person. For each of us exudes a perfectly loud and boisterous smell to a dog. What smell-science researchers have shown us is that “without a trace” really is impossible: we are always leaving a trace. A flurry of skin flakes trails from us as we move. Even when quite still, we are wafting out odor from our skin and the things on and in it. Not only that, it is still there long after we are gone. To a dog, wherever you go, there you still are.

Should this sound fanciful, consider the lowly mosquito. One could adjudge that it, too, “tracks” people. Leslie Vosshall has studied what makes people differently attractive to mosquitoes by bringing in hundreds of volunteers, putting them in what she calls a tropical room, and testing how many mosquitoes will fly upwind to bite an inch-wide patch of their exposed skin. (Being a volunteer at the Vosshall lab is not for the faint of heart.) Your body chemistry affects the number of bites you receive, but the number can also be reduced by simply creating a breeze. “A very helpful side effect (of ceiling fans) is that the mosquitoes get very confused,” she offers: the air becomes turbulent, and though mosquitoes smell you nearby, they can’t find you.II

The tracking dog cannot be so easily eluded. Unlike Paul Newman’s character in Cool Hand Luke, who successfully confuses the bloodhounds on his scent with chili powder, pepper, and curry, prison escapees are unlikely to so easily muddle a tracker. The tracking dog’s skill is not just to find the person’s scent, but, perhaps more impressively, to distinguish it from the thousands of other scents gurgling and enticing his nose. A bit of pepper may cause a sneeze, but not a system collapse.

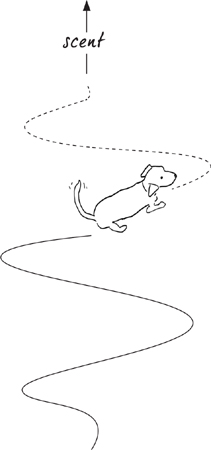

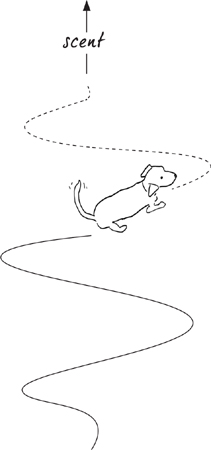

Should a track grow dim, dogs search for the “scent cone”—the invisible blooming of smelly air that spreads out from an odor source. Smell radiates from its source, getting weaker but its reach getting wider. By zigzagging, crossing perpendicular to the odor corridor, all the while moving forward, dogs zero in on their target. Along the way they engage in a kind of on-the-fly geometry to determine when the scent has weakened sufficiently relative to their previous sniff to warrant changing direction.

Not only do we effuse a strong smell, our odor lingers incredibly well on things: on gauze, on paper, on plastic, on metal. We mostly touch things with our hands, and hand odor can stick around for months on some materials. Porous objects like gloves and clothing are utterly saturated with the smell of you, but even your stainless-steel watch or gold wedding ring has you on it and in its crevices. Indeed, in training and testing handlers use “scent samples” made up, simply, of a cloth that someone held in her hand for fifteen minutes—or, for the better funded handlers, by using a specialized vacuum that traps the air above a person and deposits it on gauze. That does it.

In researchers’ parlance, our stink-wave is multilayered. We wear a primary odor all the time, part of being biological creatures. Merely sitting, doing little but turning the pages of a book, we slough off some two billion polygonal skin cells every day, along with their population of bacteria and funguses, and generate a pint of sweat (or up to five pints an hour should we up and exercise).III These include carbonyl compounds like aldehydes and ketones, alkanes, and organic fatty acids—the proportion of which distinguishes us from one another. On top of that, we are fragranced with a secondary odor of where we’ve been and what we’ve eaten. Incredibly, either in an ill-conceived attempt to hide our other odor layers or in the similarly ill-conceived notion that we don’t yet smell enough, we often add tertiary odors: perfumes, soaps, hand sanitizers, lotions, hair products, aftershaves.

The tracking dogs get all that. Lavender lotion does not put them off the particular funkfest that is your bacteria-topped, aldehydic, fatty-acid, alkane mix. And then, of course, you leave footprints. The clues in a footprint are numerous: shoe size, walker’s weight (leading to a lighter or deeper track), shoe tread. The prints themselves churn up dirt and grass and leave small bits of shoe-smell in them. But also you-smell.

Don’t think your smell comes through your shoes? Here’s an experiment for you: Stick a pair of shoes in your gym bag, zip it up, drive home, open the bag, take your shoes out, and closet them. Return to the bag. Sniff it. Smell like “shoe”?

If you’re still unconvinced, you could mimic the experiment a pair of K9 trainers did to see how much liquid—potentially carrying odor—comes through shoes. They poured water up to the shaft of a waterproofed leather hiking boot. In half a minute, water was seeping through to the outside. When walking, the boot’s exterior got more sodden. A shoe emits the liquid or gas from within it, even without the wearer sweating like mad and pressing it out. And here is how the foot odor—also gaseous, even sneakier than liquid—gets out. The soles of the human foot have hundreds of eccrine glands per square centimeter—more than anywhere else on the body—which sweat. Sebaceous glands also emit odor; the fatty acids from these glands get right through shoes and socks onto the treaded surface. Your smell, via the sweat in your feet that you are constantly, normally producing, is squeezed out in every footstep.

While tracking is thus a simple matter of following smell, what is more startling is that dogs do not need to be trained to track by smell. Of course, there is plenty of smell-training to shape good tracking behavior. Early training encourages dogs to keep searching for a scent that has disappeared; handlers walk paths that point orthogonally to the wind to help catch a smell on a breeze; dogs learn to eliminate all the other cues present in the world and focus on just the one relevant right now. This training is just as much about the handler learning to help her dog do the task as it is about teaching the dog to track.

The one necessary attribute every kind of detection dog must have, by nature or training, is this: motivation. Sometimes overwhelming, house-wrecking motivation. Successful working dogs are not gung ho to track because they want to please their handlers, find the bad guy, or experience the most intense scent. No, they are gung ho to track because tracking a smell to its source gets them one thing—the thing they want more than anything: a grubby tennis ball or the business end of a shredded tug toy. Dr. Simon Gadbois, an olfactory researcher at Dalhousie University in Halifax, calls natural working dogs the “dopamine breeds”—breeds like Border collies, Jack Russell terriers, Belgian Malinois, and huskies. They are tenacious and motivated and can focus their attention on the task they need to do to get their ball.

It needn’t be a purebred dog, though. A passion for toys, a yen for fetching and tugging: these represent characteristics of a dog who can be trained to do anything in order to sate his desire to play. If a puppy is not especially interested in playing tug, a trainer may train him to tug—confident that if it takes, the rest of the scent-training will fall tidily into place.

To describe their work, the skilled handlers of working dogs speak almost in tautologies: “The core of searching and tracking exercises,” one training handbook reads, “lies primarily in generating the desire to search and to track.” Later, the authors confess, “No dog needs to learn to search.” The point is this: dogs are natural searchers, hunters, trackers, smellers, pursuers. You only have to create the conditions for them to do it, and encourage it—ensure they keep liking the game. Such encouragement goes against how most of us deal with our dogs. It is almost as though most owners are assiduously teaching their dogs not to track. The dog who will patiently sit outside a store, waiting for you, who heels nicely and points his nose politely forward as you walk together—that dog is not destined to be a tracker. After watching tracking dogs devotedly follow their noses in search of a missing person, zigzagging in front of their handlers, seeing the familiar behavior of an owner walking her dog on leash down a city sidewalk is like watching the result of careful untracking training.

Still, training or no, watching a dog find his target through attention to invisible tracks is like gazing at a dark sky and knowing the universe sees you, but you do not see the universe. Our only access to what the dog is doing is to, well, just watch the dog. In Norway, researchers strapped a microphone on the nose of four German shepherds and set them to find the tracks of people who had secretly trodden through grass or over concrete sometime earlier that day. That the dogs could all do it (they could, in a handful of seconds) was not the issue. Instead, the researchers were investigating three distinct phases of tracking: an initial “searching” phase, ten to twenty seconds long, during which the dogs tried to find the track. Upon finding the track—about two footsteps into it—they slowed way down and entered what the researchers call the “deciding” phase. Not “deciding how I feel about this” but “deciding which way the tracks go from here.” Nose in near contact with the grass or concrete, fewer than five seconds were needed for each dog to make his decision and quickly move on to the actual “tracking” phase. The head microphones captured each snort, sniffle, and sneeze, and conveyed the news that the dogs sniffed six times per second throughout. Actual breathing was only about 10 percent of what they were doing with their nose and mouth. As with other studies, the dogs were comparing the strength of the smell of each footstep—footsteps that had been laid a second apart, many minutes earlier.

It was a garden for the blind: a constant offense to the eyes, a pleasure strong if somewhat crude to the nose. The Paul Neyron roses . . . had changed into things like flesh-colored cabbages, obscene and distilling a dense, almost indecent, scent which no French horticulturist would have dared hope for. The Prince put one under his nose and seemed to be sniffing the thigh of a dancer from the Opera. Bendicò [the dog], to whom it was also proffered, drew back in disgust and hurried off in search of healthier sensations amid dead lizards and manure.

—Giuseppe di Lampedusa, The Leopard

While dogs can reasonably, and with good cheer, be trained to detect bladder cancer or diabetes, to locate bedbugs, methamphetamine, or missing persons, every dog owner knows that these quarries are not their true specialty. If there is one thing that dogs seem to have a natural propensity for, it is, instead, finding feces. Every dog cohabiting with a cat has deep, visceral knowledge of the placement of the litter box; outside, should a neighborhood dog have moved his bowels unattended, your dog can locate it with alacrity. An urban dog might pinpoint for you, without your even requesting that he do so, either the wandering coyote’s scat or the mess left behind a tree by a local human. What’s your pleasure?

Happily, dogs are now fulfilling their natural métier. No, sorry, Upton, not “finding feces of the homeless person behind the tree in the park.” Instead, detection dogs are being put into service to find the droppings of various endangered or difficult-to-locate populations and species.

At the University of Washington, Dr. Sam Wasser is quietly heading up a dedicated facility for training and placing what he calls “professional poop chasers.” Or, in the terse nomenclature of science, “scat-detection dogs.” I have come to meet Wasser on an early morning at the Seattle campus, whose broad open spaces are mostly empty of students at this hour. A dense fog hides Mount Rainier, which should be proudly rising to my southeast as I head into Johnson Hall.

Though I have come to talk to Wasser about dogs, wildlife is his main concern. His detection-dog program, Conservation Canines, did not grow out of an interest in dogs. In the late ’70s, Wasser worked in Mikumi National Park in Tanzania, Africa, studying yellow baboons. Like many other wildlife researchers, he was in the business of collecting information about the behavior and health of his chosen animal population—in his case, the reproductive competition between female baboons. Typically this information is gathered by stealth, trying to keep out of the animals’ way and, instead, setting up camera “traps” that catch their movement, hair snags that pull hair samples (yielding DNA) as the animals wander past, or tagging or collaring animals and releasing them. Each method has shortcomings, from sampling bias (some animals are more likely to be caught than others), to the time and expense required to catch and release animals, to the stress and sometimes fatal injury from the tagging. Lures can change the target animals’ behavior; trapping can injure them; even wearing a tag can fundamentally change the population dynamic.IV

A better way to find out about living populations would be to treat them archaeologically: to see what they leave behind. Like bad visitors to a hotel, animals leave evidence of their activity in their wake. They graze, abandon nests, trample ground—and, most shamelessly, poop as they go. It is that poo which captured Wasser’s interest.

A bit about poo. Generally, we think of excreta as worthless, without value. To call something shit is, pithily if not wittily, to observe that it is devoid of use or merit. Not wildlife shit. Researchers see shit and think: gold mine. There is information in that scat: information about health, reproductive status, what the animal is eating, and how it is feeling. The DNA allows identification of individual animals—who it is, the age and sex—and provides a way to determine relatedness among the animals. Scat samples allow researchers to reconstruct how large a species population is and how widely it’s ranging. Oddly, this nearly perfect collection program is such that animal researchers can gather considerable information about their subjects without ever seeing the animals.

Now Wasser’s concern is the demands that human growth puts on wildlife. The scat samples allow him to suss out how the health of animal populations is changing. But the poop business began with the baboons: “I was on a mission to try to get DNA out of feces,” Wasser tells me. Collecting feces could be a trial: trying to be there at the moment of production, as it were, or ferreting around in the dirt when animals had moved on. “I realized, wow, if I could figure out a better way to collect it, that would be great.” At a conference on bears, where the banning of hound hunting—using hounds to find bears to shoot—was being discussed, he met a hound hunter bemoaning what he would now do with his dog. The dog, he claimed, could go forward and backward to follow bear tracks. Wasser was transfixed. “I was like, Oh my God, that’s my scat-detection dog.”

As it turned out, he really needed an air-scenting dog, not a ground tracker like a hunting hound, and over time Wasser met and got involved with narcotics-detection-dog programs, including at McNeil Island Corrections Center in Puget Sound, to observe their dogs and training methods. “The dogs were un-be-LIEV-able,” he swoons. “The prisoners would take off their clothes and go to the laundry and the dogs would just smell everyone and go yup”—he snaps brightly—“that guy’s got drugs”—snap—“that guy’s got drugs”—snap—“and that guy’s got drugs.” Wasser was convinced.

He began training dogs. His lab’s first study was searching for grizzly bear in Washington State, in a place called Goat Peak. They never saw the grizzly—but the dog told them one was there. Then he performed a large study of grizzly bears in Alberta, Canada. Wasser regularly experienced the whiz-bang spectacle of his dog’s nose: “I’m sitting there,” he remembers, “and the dog sticks his nose in this hole—I reach down in there and here’s this grizzly bear poop.” Another time, they encountered a raging river, “and the dog jumps over the river and hits”—alerts on—a “tiny poop” in it.

Wasser’s projects grew in size. Before long, his dogs were surveying over twenty-five hundred square kilometers in Alberta, Canada. Even in the deep snow in winter, they found thousands of scat samples from caribou, moose, and wolves, which let Wasser determine that oil-exploration activity and roads were changing the behavior of the animals. The closer the herds were to the crew activity, the higher their stress levels. He was able to tell, from scat alone, what each species was eating (wolves: mostly deer) and their seasonal variations in nutrition and stress levels. Human activity turned out to have the biggest effect on caribou populations, not the wolves that so many accused of consuming them.

Since then, Conservation Canines has trained dogs to find the scat of jaguars, tigers, and wolverines; Townsend’s big-eared bat, the Sierra Nevada red fox, and the Pacific pocket mouse. Nor are the dogs mammal-centric, crossing the animal class borders to find sea turtle nests after the BP oil spill, determine the population of the northern spotted owl in northern California forest, and count the numbers of endangered Jemez Mountains salamanders, which live in dead logs and come out only one month a year during monsoons. Dogs may be trained on up to twenty species: once trained on one, adding another species comes easily. And yet they have little trouble distinguishing scat from different animals, even from closely related species, and will ignore the universe of nontarget scat around them. To alert the handler that they have found the scat, they simply sit. Not pick it up in the mouth or roll in it. Sit.

Unlike many detection programs, Wasser’s dogs are mostly young mixed-breeds from shelters—because that’s where dogs with excessive energy and borderline-obsessive personalities wind up. A dog with what he calls, gently, “fixation with the ball,” a strong play drive, and high energy is that classically motivated dog that all programs love. “These are the kinds of dogs people think, Oh my God, you’ll never be able to control this dog,” he says. But “they never run away—because you’ve got their ball.”

Next to Wasser’s computer is a calendar featuring a number of the Conservation Canines. May 2015’s dog is Tucker, who has perhaps the most unlikely and spectacular job of them all. In the calendar he sits patiently on a boat with a yellow life preserver around his neck. What this sweet-faced black Labrador retriever mix does is detect the slimy scat of orcas—killer whales—who live in Puget Sound.

The resident population of orcas in the area has declined precipitously, and Wasser thought that information about their diet, hormone levels, and possible toxins could help identify why this is happening. That’s in their scat—but orca scat, though smelly (think: fish) and sometimes even yellow or orange (though usually brown or green), is buoyant for only a short time and then sinks. It is not easy to find in the great wide sound. Not for Tucker. “Tucker is amazing,” Wasser says. “He smells a sample over a nautical mile away and is able to track it over a fast current.” Wasser is talking quickly and then stops for that fact to sink in. Though orcas are large, their scat is not highly visible. To find it before it sinks, the team has to be speedy: in choppy water, it sinks nearly at once; even in calm seas they’ve got only thirty minutes to find it.

The researchers take Tucker out on the boat and head in the direction that orcas have been seen, driving downwind of the animals with the wind at the boat’s side. That way, they are potentially maneuvering into the scent cone (the V of the odor dispersing from the scat), perpendicular to the wind. “Tucker is asleep on the bow of the boat. But you can see his nostril going”—Wasser flares his own right nostril, which comes off like a wry grimace—“and then all of a sudden as soon as you hit it”—snap—“he is up.”

“This is the most convincing of all the work that we do,” he says. “There’s no landmarks; the current is pushing these samples . . .” But when they enter the scent cone, Tucker stands up over the bow, his nose down, and essentially points with his nose toward the source. If the boat goes too far by it, he runs to the side of the boat. His nostrils go up and down, side to side—wet-nose rudders directing his handler how to steer the boat to reach the source.

Wasser smiles remembering how hard it was for them to see at first what Tucker was doing. In the first year of the project they never found scat. But it turned out not to be because Tucker wasn’t spotting it, “but because we couldn’t believe he had it that far [away]”—and so they would stop the boat and turn back. When they began baiting pie pans with samples, letting one boat follow the pan visually and the dog boat try to find it, they realized that even a mile away, Tucker was actually leading them to the pan.

At the scat, the researchers gently scoop up the sample with a little net at the end of a telescoping pole. Meanwhile, the handler gives Tucker his reward: his well-loved tennis ball. Eventually, Wasser gets his tennis ball: a well-founded result. Given the hormonal and nutritional levels that varied seasonally, he concluded that a reduction in the animals’ primary prey, Chinook salmon, seemed to be driving the population’s decline.

While one could, in theory, put the orca scat through the gas chromatograph to figure out what the volatile elements are that Tucker might be detecting, for Wasser, the evidence that he can find it at all is sufficient. Still, he acknowledges that there is some ambiguity about what part of the smell the dogs actually believe they should detect. For instance, he discovered that dogs trained on the sound’s resident killer whale population—what Wasser called the “fish eating dogs”—were not alerting to the “transient” orcas—the ones just passing through. The transients are mammal-eaters. “We had trained him on killer whale [smell] plus fish,” Wasser realized. Without the fish smell, the dog didn’t interpret the smell as “orca.”

But the dogs are ingenuous: they are just trying to get it right, based on what their handlers reward them for. “The handler is the hard part” of training the dogs, Wasser says. “Way harder than the dog.” When training a dog, there comes a point when the dog-handler team moves from working with samples in a controlled setting to beginning to search in the wild. But scat in the wild will never smell just the same as the frozen, thawed, and refrozen sample from early training: it may be newer or older; the bacteria on it is different; it is from a new animal. The dog has to see what is the same between both samples, and begin alerting to that. Sometimes, though, if the team does not find a sample quickly, “You’ve got this highly motivated dog that wants its ball more than anything and an extremely anxious handler—because the handler loves the work and is thinking Oh my God, I’m a failure. And now the dog stops and checks something out and goes, Will this work?” Wasser looks at me from the side of his eyes, eyebrows up—the questioning, hopeful dog. “Is this what you’re after? And then the handler goes, Oh, well, let me see, and the dog goes, Oh, I guess I’m right, and he sits down, and the handler goes, Oh, he’s right and throws the ball. Next thing you know you’ve layered the wrong species onto the dog.”

Even with that nose, a detection dog will look to his handler to confirm he’s correct. The handler has to trust the dog enough to let him finish his job. There is not just dog anatomy involved in detection; there is human psychology.

To Wasser, there is no downside to working with dogs. Sure, it might be hard to move them around sometimes—they can’t be stashed under the seat in front of you on the plane—and they are individuals, with their own temperaments and moods. But a piece of equipment—an electronic nose—would never replace the dog. “The one thing about a dog is, they improve with time,” he says. And, I might add, if you’re spending the day finding animal scat, there must be nothing like having an energetic, furred, devoted partner in crime.

• • •

Lyall Watson writes of a hound tracking a missing man by following a week-old trail through a bank and a grocery store, crossing traffic, and ending at the bus station. Indeed, at the very bench where the man was later determined to have briefly rested before boarding the bus. When I hear of stories like that, or of Tucker’s orca-tracking, and remember, by contrast, my immediate and complete bafflement as to where my dog, Pumpernickel, had got to on that day she left the house, I think that dogs and humans have nothing in common. It seems a dog can find another animal, but it is very hard for a human animal to find a dog. But maybe I wasn’t hanging out with the right human animals.

Members of the Kanum-Irebe tribe in New Guinea, as described by anthropologists, have a parting ritual that may be alien to most Westerners. When two friends are saying good-bye, one reaches into the armpit of the other, “sniffs at his hand, and rubs the smell on himself,” therewith eliminating the disturbing possibility that “he cannot stand his smell.”

We do use each other’s smell—if usually more unwittingly. At some level, we know that our own smell reflects what we eat; that we smell our age; that we smell like our smoking, drinking, and swimming habits: and so do others. Our odor reflects our mood, our health, our occupation, our medication.

Rarely do we overtly attend to or seek out these smells of others, though. But, like the Kanum-Irebe, we may actually collect others’ smells—if subliminally. The now notorious research result that the menstrual cycles of women who live together spontaneously synchronize shows, in essence, a detection of others’ odors, with a specific physiological result. And recently, psychologists covertly videotaped hundreds of subjects’ behavior right before they took part in a (mock) experiment. The actual experiment happened in this pre-experimental time: greeted with a handshake from the researcher, people actually appeared to sniff their shaken hand shortly afterward. With same-sex researchers in particular, the subjects brought their hands near or to their noses after shaking hands, and sniffed. It was as though they were sampling the smell: what the researchers called “chemo-investigation of conspecifics.” Smelling you.

Certainly most of this chemo-investigation is unconscious. Can people intentionally track other people or other animals by smell? I resolved to find out.

The porcupine is a messy animal. Compact, his body covered with tens of thousands of hairs modified into barbed quills—which, famously, a feisty porcupine can release and drive into the flesh of anyone foolish enough to come near—he is well armored. Before he does that, though, the porcupine will clack his teeth at a potential predator, and release a penetrating odor from glands on his back. He would rather not get into a scuffle.

It is, perhaps, the many layers of defense that the porcupine, Erethizon dorsatum,V has, that allow him to be so, so slovenly. The porcupine pees where he pleases, often while walking along, not bothering to slow or stop. The footprints of a porcupine may be peppered with bits of dirt or defecation, as he sleeps in a den piled with his own excreta. Unsurprisingly, he does not groom himself. When animals groom, they are doing so less out of a sense of the importance of cleanliness than out of a fear of predators scenting them or pests injuring them, or out of an interest in mating with other like-minded animals. The porcupine handles predators with aplomb, seems to have a hearty immune system, and has figured out the mating game even with all those quills. So he gets to be unkempt with impunity.

His grubby manner is how it came to pass that I could tell a porcupine was near us in the forest, one cold January day. Reader, I caught a waft of porcupine urine.

• • •

The day had begun eight hours before, under three layers of night that gradually yielded to day along my drive from New York City to western Massachusetts. I had risen early to go animal tracking. If there was anyone who could rival the scat-detection dogs, it was scat-detecting animal trackers. I was headed two highways and a string of desultory industrial towns away from where I awoke, where I planned to meet Charley Eiseman and Noah Charney, naturalists with an ecological, philosophical, and purely hedonic interest in finding the tracks and sign (read: often scat) of animals.

In the dark of the city, I kissed the top of my son’s headVI and headed outside to my car. I thought to sniff the city’s nighttime air, knowing that I would soon have a contrast in the bright, cold western Massachusetts climate. I had to work my nostrils a dozen times to notice anything at all. The city smelled ashy—dusty, maybe. It smelled like . . . absence.

• • •

In the excitement over dog-tracking ability, one might forget that humans have a long and storied history as trackers themselves. Certainly, as an omnivorous species, and before being an armed species, we humans found and trapped animals for food simply by knowing their habits: where they lived, what they ate, when to find them out and about and vulnerable. These days, apart from sport hunters, people rarely track animals to find dinner; instead, the extant “animal trackers” are hunting animals largely to photograph them, to survey the population, or to feed their own inquisitive spirit. In this way, contemporary animal tracking is a curiosity rather than a necessity. So, too, for the kind of “tracking” a contemporary American pet dog might do: for the great majority of twenty-first-century dogs, following their nose is less about finding a mate or dinner or minding territories than it is simply noticing what’s around them.

The phrase animal tracking gives the impression that the end result is finding an animal, but this is not so. The most likely outcome is that one will not see the animal at all. Nearly every wild animal will notice a human wandering in its midst well before the human notices the animal in his. Instead, tracking is about discovering the various indications that the animal has been by. The classic sign is an animal’s tracks, or footprints. Since we were headed out into a mostly untrammeled forest, where snow had fallen a few days before, there would be clear, discernible animal footprinting for us on this day. Mud is also a fine substance for catching the footfall of the passing coyote, turkey, or moose. Most terrain, though, does not capture the forest’s populations’ light footsteps (such that humans can perceive it), and most weather—rain, continuous snow, wind—is well designed to wash any traces away. A tracker often doesn’t have, and doesn’t need, actual tracks to track an animal. Any forest is, down to each hillock, to every tree and shrub, wearing evidence of the animals that live there. All of our senses, and all sorts of evidence, are used to trace the passage of an animal—including their smell. Deer smell. Squirrels smell. Bears, bobcats, foxes, and moose smell.VII

What might a moose smell like, you ask?

“Oak-y,” says Noah Charney, as, nose in the air, he cuts a corner on our path and wanders among a grove of trees. “I thought I smelled a moose.” He pauses. “But it [both the moose and its smell] is gone now.” Watching Charney nose-hunting for moose is like watching an art appraiser eyeballing the ostensive masterpiece placed before him: while one can see him looking, one has no idea what he is looking at.

What Charney, and every animal tracker, does is learn to embody the animal he is tracking. To understand where the animal might be, one has to think like that animal—to imagine its life. The skill of tracking has been compared to learning to read: only one reads not the grade school primer, but the forest. As a book’s hieroglyphics morph into legible prose to the young reader, a wilderness begins to look the way it might to the animals who live in it. What bush would thoroughly conceal you, if you were a rabbit? What manner of tree presents the perfect height and visibility for a bear to announce her presence by rubbing and clawing along it? Which secret hollow appeals to a flying squirrel? What time of day might the nearsighted possum feel safe foraging with her pink grubs of pups? Once one sees the world like the animal, becoming aware of oneself in that space, just as the animal is in that space, one finds traces of the animal.

Of the animal tracker’s bag of tricks, it is the tracking of smells that I am after, of course: the odorous sign of an animal’s passage. Heading up north in my sealed-off car, I have only a vague idea exactly what those signs might be. When I nuzzle my nose in the scruff of Finnegan’s neck, I surely recognize his smell. I have learned that when guests come to our door, they note the distinct odor of “dog”; we, who inhabit the house, have become so accustomed to the fog of dog that we cannot smell what they smell.VIII Surely Finn wears, or emits, other odors, but even in our close companionship I have never thought to loiter on them. This is about to change.

• • •

It is still the early hours of dawn when I pull up to the tracking-school classroom building. It is deeply cold: eight degrees Fahrenheit. The deepness of the chill is heightened by the stillness of the morning. Cold, calm winter days are good for ground tracking, the animal-tracking manuals say, presumably because, apart from the recent animal smells, all the other volatile odors of the world—from tree, plant, and earth—are quietly asleep beneath the cover of snow. The warm touch of an animal is a beacon of odor in a cold scene; this warmth even volatilizes whatever it touches, creating bubbles of odor in a barren landscape.

I want to properly prepare my nose. Admittedly, this preparation is pretty straightforward: I blow. Make room, remnant city and car smells: I need to smell coyote! For good measure, I’ve brought along a nasal steroid recently prescribed to clear some congestion plugging my ears. It can’t hurt, I figure, to be a nose on steroids. “If I wanted to improve my [scent] detection,” Stuart Firestein had admitted to me, “I would use steroids.” He was not making a doctor’s recommendation, just an observation based on his own past experience. Due to an oral surgery, he needed a nasal steroid temporarily. “I smelled things I had never smelled before,” he waxed rhapsodically.

The spray is like a sudden injection of a lily into my nose, petals, pistils, pollen, and all. As I inhale, I can feel my nasal passages opening, stretching their arms and widening their eyes to the daylight. If there’s any time that my nose might be a super-nose, it is now.

Inside, I find Charney and Eiseman in a small, busy classroom; Charney lifts his eyes in the briefest of greetings. They both share the same unruffled manner. Both are dressed comfortably in muted layers. Two packs are laid out across the chairs, spilling supplies. Their equipment has the specificness of those who are prepared to be outside for long periods, but who do not like to be over-prepared.

Shortly, a half dozen tracking students stumble in, all heavily dressed for the day’s expedition. “The bulk of our time will be spent in the field visiting local habitats,” the course description had warned, telling students to “be prepared for long days in cold, wet, and strenuous conditions.” Hand warmers are in evidence.

Charney approaches and wordlessly hands me something. It is an eighty-page tan Steno Notes notebook, its pages plumped with wear and water. His tracking notebook: the repository of notes and ephemera from past expeditions. “Noah’s scratch-and-sniff book,” Eiseman calls it, because it contains physical leavings and evidence in the form of fur, leaves, sticks—and in the form of tissue paper sodden with urine.

I handle it gently, as though it were an ancient scroll. On one page, a long, tassel-like hair is taped on the page. “Moose” is scribbled by it. On another, “Fox, 12/27/01.” Some pages hold a series of twigs with incisor marks, or clumps of fur that seem not to have fallen from their bearers naturally. There is sign of rabbit, caribou, bobcat, possum, bison. “3/03 Beaver” holds a patch of beaver hair; under it, “Coyote,” and a tissue once moistened with, presumably, coyote urine. I wonder whether that coyote and that beaver met on that day; I sniff the page. Riffling the pages through to another tissue, I sniff that one, too. Apart from the surprisingly clear “Steno notebook” smell, I can detect that there are some kinds of smells, but they betoken nothing.

Jammed between two of the final pages is a sample with High Security, for the field: a crumpled tear of aluminum foil is wrapped around a ziplock bag—itself securing a folded tissue. A note on the bag reads, “Red fox, 1/9/03.” Charney carefully extracts the sample, which has not seen fresh air in twelve years and four days. He barely touches it to his nose, with the gentleness of a man sniffing a woman’s handkerchief. “Oh!” He has a physical response to the odor, pulling his head back and striding across the room away from it. I take a turn with the tissue. My nose catches something sweet, animaly. Eiseman leans toward it. “Skunky!” he says at once, smiling.

Charney nods. The simple syntax of animal-urine odors seems to be: name of animal evoked (skunk) or food source (oak), plus punctuation to reflect the intensity of the odor. Skunky! works for both skunk and red fox. Musty, for a bear. To both Charney and Eiseman, this odor is exclamation-point loud—and patently from the elderly bladder of a red fox.

Eyeing the tissue, I feel a bit like a color-blind person in a room of rainbows: I sense there is something to be seen, but my searching eyes can’t find it. Charney hands the tissue to the students, hesitantly poised at the table in full winter garb. Each willingly brings it to her nose and sniffs it. Last week, before the class, such an offer would certainly not have been accepted by any of them—or, I daresay, by many outside of this class.

Charney is the exception. “I’ve always smelled everything,” he tells me, “for as long as I remember.” He tells a story of living temporarily in a wigwam in the woods while he took classes by day. Returning to the forest in the depths of night, he had to navigate by smell. “One time I did wake up and I didn’t know where I was,” he admits. Usually, though, he found his way by following his nose. Remembering my lack of familiarity with the smells of my own block after smell-walking through Brooklyn, I comment that this may be atypical. He shrugs it off. “I’m always surprised [at the things] that people can’t smell.” He laughs, a bit vexed. “I’m like, Why not?”

That Charney does not see his exceptionalism is obvious in his description of meeting his wife for the first time. What he remembers, he says, is that “when we first started dating, she smelled like Coca-Cola.” He recalls his childhood as redolent of his toys: “The plastic tires on those little plastic toys? They smell this really strong vinyl-y kind of smell . . . And the whole reason to play with Play-Doh is the smell of Play-Doh.” As with perfumers and wine experts, when he describes the vinyl smell of toy car tires or his wife’s cola ambience, he is not just remembering the smell abstractly: he is smelling it in his head.

This ability to invoke odors, to smell-daydream, as it were, is a clear marker of those who know how to use their noses, and those who do not. It marks attention, the brain’s willingness to loiter on an experience, which is later conjured up. Some people experience smells in dreams—though even normal smellers seem to have their dreams affected emotionally by odors in their environment.

Though odors have emotional content, for Charney, they are simply a part of the scene, and a customary note of his daily experience. He has odor preferences, as we all do; where he differs is in his approach to the vast expanse of odors that are not naturally pleasing. “There are smells I hate. But I still like to smell them—because it’s like, Ooh, that’s horrible.” He grins. What kind of things, I wonder. “You know, vomity kinds of things,” he replies.

Oh.

• • •

Everyone piles into a van and we head farther from highway and habitation. Our destination is the northern end of the Quabbin Reservoir, a water source for Boston surrounded by state forest. Charney drives and Eiseman plays bird songs on the radio. Apart from being in the outdoors, this is clearly their element, listening and smiling and nodding in recognition of whoever sings tuh-wheee!

After an hour we park and tumble out of the van. The forest at the road’s edge is a wall of undergrowth and fallen trees and branches; there is no obvious path. Charney simply pushes a branch aside and walks in. After a beat, we all follow him. The woods immediately swallow us. There are occasional animal “runs” that serve as makeshift paths, but we mostly bushwhack through tall, tight reeds and bushes, forging serpentine routes between low branches of close-growing hemlock and white pine.

A dozen minutes in, the only signs I can detect of where we might be are our own footprints in the snow and the ascending late-morning sun from the southeast. I am engrossed in the activity of minding where my foot is going to step, and notice little else about our surroundings. But the trackers have their heads up: while I walk, they investigate.

Charney stops. “Do you see this? Have a look.” And he walks off, leaving us to examine the tree he’s gestured toward. On first examination, it is, unquestionably, a tree. Nothing remarkable about that. Then our eyes shift. It is damaged—there is a tear, or some holes. Peering closely there is a single hair—a hair!—sticking horizontally out of the bark. It feels like a miracle to see it. Charney returns. “Did you find the hair?” It had popped out at him, bogglingly, while he was striding by. He then diagnoses the scene: this is a tupelo tree, in a bit of clearing, on a small hillock over what are now-frozen wetlands. Nearby are a handful of larger tupelos.

That is what the tracker sees first. They see that setting as a great fire hydrant on which a female bear might leave her mark. The trunk damage: bite marks and scratches from her broad claws—both ways to leave her scent behind as a warning to competitors. The hair? From rubbing her back against the tree’s trunk. Those larger tupelos could be “nursing trees”—up which a mother bear can safely stash her cubs while she forages for the tree’s coveted berries.

I peek around me carefully. No bears in sight. Still, the air is charged with the scene evoked by the traces left behind.

As we carry on, we slowly but surely collect animal sign: the track of a flying squirrel, which begins suddenly (its landing site) and quickens to the safety of a tunnel at the base of a nearby tree; cottontail rabbit; deer so frequent they are unremarked upon. Sign can be claw marks or shed hairs; traveling paths forged through close undergrowth; depressions in grass or fur where an animal lay and nested. And excretions: droppings, secretions, other often mephitic exudations. “There is a whole novel in an owl’s pellet,” a tracking guide book rhapsodizes. The book is chock-filled with full-color photographs of scat and mucuslike blobs, centered respectfully in their frames. The novels written by excreta are portraits of the excreter: his species and sex, health and diet, preoccupations and companions, and daily routine. A coyote’s scat is filled with fur or hair, contrasting it with dogs’, rife with the grains that make up packaged dry dog food. A pile of lake muck, topped with a yellow-orange smudge, is sign of a beaver feeling territorial.

The human tracker may constitutionally be directed by his eyes, but his nose brings more information still. An experienced tracker like Charney can air-scent, if the air is sufficiently humid and the wind is at his face. But to do as the animals do, it is also useful to get at animal-height: the “stick your nose right in it” method. The general instruction to “get down on your knees, put your nose as close as possible . . .” (as one tracking bible says) is anathema to most people. But Charney regularly drops on all fours, his face a half inch from a moss-covered stump or tree trunk. He races ahead into a clearing; when we catch up with him, he is getting up from sniffing a wide stump. Everyone takes a turn on their hands and knees, nose up to the broad vertical shelf of the trunk. “Remember to blow some warm air on it so the smells come up,” he advises. Whatever odor is on that trunk, it needs the warmth from our lungs to make it volatile, to evaporate into the air and be captured by a sniff. Similarly, the lightest of rains can “breathe new life” into otherwise quiescent odorants on the ground. I warm the trunk with a breath, close my eyes, and sniff. I smell a mustiness, reminiscent of basement. Eiseman is smiling: he already knows what animal has been here, just from the context. He confirms it with his nose. “Cats in a basement,” he corrects me. Here, bobcat. What I recognize as basement is actually the smell that my past cats have left there.

There are no footsteps, no other obvious sign of an animal being by. So how did Charney know to sniff just here, then? “You have to think about whatever is prominent for the animal. I just look around for all the places that might be interesting to mark,” if you’re an animal that urine-marks—a single item sticking out in an otherwise undifferentiated scene, say. And “context-wise, this area”—with a stump alone in a small clearing—“looks good” to attract a marking feline or canid. And then you smell.

Bobcats are so specific in their marking habits that animal trackers can be likewise specific in where to look for their marks. “Urine deposits are usually eight to nineteen inches above the ground,” one book instructs. “The most common scent post is a short, decaying stump, usually not more than six inches in diameter and four and a half inches high. If the stump is leaning, [bobcats] usually deposit urine on the underside where it is better shielded from the elements.” We had aimed about fourteen inches above the ground, on a decaying stump with a lean.

Indeed, a good amount of smell-tracking lies in using vision, too. That’s fair. Dogs, certainly, use their vision. Their being olfactory creatures does not preclude their looking: they don’t find another dog’s rump only by air-scenting. They may see the body first and follow it to its derriere: then they sniff. The whole point of scent-marking on a fireplug is that it is easy for the next sniffer to locate. The sight of a stump in a forest clearing presumably does for the forest-dwelling animal what the sight of a fireplug does to an urban dog. And I, at the other end of that dog’s leash, see it, too, and know where he will lead me. That behatted, upright fireplug planted right along a boring flat stretch of sidewalk: that’s a fine place to put a mark. Footprints—another visual clue—might lead one to a likely smell site. And so it is with animal tracking.

On top of the contextual clues, we could eliminate the possibility of the marker being a canid even before putting nose to stump. If it had been one of the local wild canids, the red fox, “we’d be able to smell it from here,” Charney says, stepping back eight paces. “A red fox really assaults your nose.” Trackers tend to call red fox urine “skunklike,” much stronger than domestic dog, coyote, or gray fox urine. Unlike the relatively modest—if not exactly pleasant—ammonia of the bobcat urine.

We eat lunch on the frozen wetlands, glad for the cloudless sky. I turn my face to the sun and curl my fingers into fists after quickly downing my thermos of tea and sandwiches. For a while, everything will smell to me like peanut butter.

When we continue on, conversation has dimmed, but the sound of our footsteps obliterates any other sound. We are not quiet animal trackers. At a broad trail I hang back from the group to listen to the forest. The day has warmed under the steady sun, prompting the crystalline sound of tree ice showering onto lower branches. I take sniff-samples of the air; I sidle up to trees and surreptitiously give a sniff. I feel the cold in my nose and can almost taste the clarity of the country air.

Ahead of me, footprints form a track. To my naive eyes, it appears to be bisected by one or more indistinct sets of tracks running across it. I follow the track down off the path and into an area of low brush. There, near a little spring of a hemlock, is a dribbling trail of light yellow. I stop.

Now, I’ve seen a lot of pee. I live with dogs, after all: which is to say, I spend some time every day overseeing my dogs’ urination. Indeed, one of the strangest things about being an urban dog owner is that we owners have great insight and attention to the evacuations of our charges. We know their methods (leg-lift, squat, squat-and-scoot, sniff-and-circle), their preferred locations (in the curb, on the hydrant, with grass or leaf litter underfoot), and even the expected quantity of output. I’d hazard that, accidentally, we are familiar with the smells of our dogs’ urine, just as parents become intimately acquainted with the sweet odor of their own newborns’ blissful defecations and micturitions, simply by constant exposure.

So I barely hesitate before kneeling in the snow, crouching low, and sticking my nose ever closer to the yellowed snow. And I smell . . . porcupine.

Porcupine pee smells—there can be no question—piney. In the winter, the animals subsist mostly on the bark, leaves, and buds of pine trees. Scattered hemlock branches on the ground, incised at 45 degrees to vertical, are evidence of the foraging of this particular porcupine. They climb trees, gripping with their impressive claws, and make their way out to the ends of branches, holding the newest of the new growth. This arboreal habit, while providing them with ample calories, is also sometimes responsible for their ends: a porcupine who falls off a tree lands on many sharp, impaling quills—his own.

I stand up, beaming, and glance at Eiseman. “That might be my favorite animal-pee smell.” He smiles. Well, if you’re starting with the “smell of urine,” I have to agree: it isn’t too bad. Woodsy and strong, but not overpowering; I’ve smelled much worse in NYC taxi air fresheners. We follow the footprints leading away from my find: the back feet come down slightly ahead of where the front feet lay—an “indirect register.” The toes point out, befitting a waddling, short-legged, chubby-bodied animal. Aside the toe holes are lightly rendered lines drawn by the quills grazing the snow; within them are small chunks of dirt and forest debris. The profligate peeing, the messy trail, the distinct shuffle: porcupine. “Porcupines and red foxes are the animals that I will often smell a hundred feet away,” Eiseman adds. “I only sometimes see the animal.”

Do their tracks themselves smell? “I’m sure that to a fisher”—their most common and successful predator—“they smell.” To a porcupine, too, perhaps. Nosing a four-toed footprint,IX I confirm that I have neither porcupine nor fisher genes.

We follow the trail to its end—a den with remnants of a stone wall on three sides—and peer in hopefully. This might have been an icehouse a century ago, before the state flooded the four towns in the area and created the nearby reservoir. Instead of porcupine or porcupette, there is a towering pile of pellets, many feet high, in either corner: insulation for a cold winter. As the wind turns, the fecal smell floods the air. If the quills aren’t deterrent enough, this could prevent other animals from trying to steal the den.

• • •

Midafternoon. We stop at a frozen beach, taking in some more of the sun’s warmth and gazing out at the long expanse of iced lake at our toes. Twenty feet out on the ice, the trackers are looking down.

“Hey, Alexandra, there’s coyote pee!”

Rarely has this utterance inspired excitement, anticipation, or thrill. Or, I’d guess, a quick jog toward the informant—as I set to do. As I approach, I can see that Charney’s nose is inclined toward a small twig frozen into the ground, protruding only a few inches. A single dried leaf shivers from its top, and an expanse of moss is wrapped around it. At a few inches tall, it isn’t much to look at—but it is the tallest thing around. Looking out to the ice and around my feet on the beach, numerous trails clearly converge on this local landmark. It’s perfect for a coyote, who prefers to mark highly undistinguished items. The coyote passes by the towering oak without breaking his stride; he snubs the ancient hemlock, the prehistoric rock outcropping. No, it’s “small bushes, tree trunks, rocks, blocks of ice, mounds of snow” that shine brightly in the coyote’s eyes. This twig is just right: though only noticeable to the human when she trips over it, it is nonetheless a single bump in a sea of flatness. The tracks are about a foot from the twig, indicating that this was probably a male, who could reach the twig with a spray under a lifted leg, rather than a squatting female.

I crouch and hover over the stick. There is a splash of yellow on the snow, a more profligate leaving than the single droplets doled out in the forest. I sniff. Smoky, earthy. Incredibly strong.

“Doesn’t have the skunkiness of a fox,” Charney offers. “Pure ammonia,” Eiseman says. “A lot milder than fox.” Charney leans in and takes another whiff—“Whoa!”—and he keels over, flat on his back, in mock (partially real) horror. “There might be a domestic dog involved here.” Meaning, this smells like an animal that is eating a different sort of diet (one coming out of bags and off of kitchen counters).

Indeed, though the large, loping footprints converging on the stick look like coyote, some tracks are much more disorderly than the others. The dog’s gait is, in fact, considered “sloppy.” The dog indirect registers—leaving twice the footprints. His nails make distinct nail-marks, spreading out from the pad, unlike the tucked-in pithiness of the coyote print. The dog’s course is meandering. “You just don’t see wild animals making some of these tracks,” Eiseman explains, “because they’re trying to conserve energy.” Coyotes’ paths are clean, straight vectors from A to B; they “direct register,” back feet stepping in the front feet’s track. They cannot afford to explore every new thing, every which way. This wandering track is from someone that’s getting fed.

We linger a bit at this perfect scene. Not an animal in sight, but sign of animal all around.

The sun’s quickening descent tells us that it’s time to find our way out of the forest. Though we have wandered for hours, over many miles, my guides seem to know just where we are and beeline for the van. “Every forest has a smell,” Charney suggests as we walk. “This one smells like the leaf litter when there is no snow,” says Eiseman, “of the blueberry and gorseberry undergrowth.” If they were dropped into this scene, blindfolded, with no wind on their faces or sound in their ears to go on, they could still identify where they were.

Eyes open, ears on alert, nose exercised, I try to take it in. Back in the city, hours later, I can distinctly smell my urban forest. In the first half of the twentieth century, the MTA—the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, responsible for running the city’s subway system—employed James Patrick “Smelly” Kelly to walk the tracks and sniff out any gas or water leaks. His skill was legion. Once, presented with the complaint of a bad odor beneath the subway a block off of Times Square, he arrived at the site to find distinct odor of elephant. Indeed, it turned out that the Hippodrome, which housed many a traveling circus, had been at Sixth Avenue and Forty-third Street, right above the station. Apparently the circus elephant dung had been left behind, and its smell was reanimated by a nearby water leak.

I sniff for, and do not find, elephant in the city air. Often the city’s smells are noticed only when foul, but now they feel neutral, informative. I breathe them in with satisfaction. But I do mourn the lack of a certain pure, icy northern snowflake in my nose.

I. To the great delight, no doubt, of Dahl-reading youngsters everywhere, the tactic to avoid witches is to “never have baths”—thus curbing the stink-wave-dispersal with layers of dirt. Alas, in Dahl’s version of the fairy tale Jack and the Beanstalk, Jack only escapes being smelled out by the giant (“FEE FI FO FUM . . .”) by bathing, emerging “smelling like a rose.”

II. If you are, like the author, a person who not only attracts many mosquitoes, but also redirects the mosquitoes initially keen on your nearby friends and family, take these two bits of wisdom from Vosshall’s work: stay downwind of the critters, and stay near fans.

III. One researcher fancifully quantified the smell “pollution” generated from one “standard person” (skin surface 1.8 meters; takes .7 baths a day), when sitting, to be 1 olf. Someone exercising may produce up to 11 olfs; a smoker, 25 olfs.

IV. This was well represented by the study of reproductive choices of zebra finches: females turned out to prefer the males not with physical extravagance or prowess, but those accidentally assigned red, not black, leg bands for tracking.

V. Which translates roughly as “animal with the vexing back.”

VI. smell: sweet, sweaty hay.

VII. In her wonderful volume A Nosegay, Lara Feigel quotes the story told by Edmund Snow Carpenter in Eskimo Realities (1973). He recorded this exchange between an Inuit woman (W) and an anthropologist (A): W: “Do we smell?” / A: “Yes.” / W: “Does the odour offend you?” / A: “Yes.” / W: “You smell and it’s offensive to us. We wondered if we smelled and if it offended you.”

VIII. This phenomenon is called habituation: no longer noticing an odor after repeated exposure. While it is similar to adaptation, the latter operates at the level of the receptor cells; habituation is a result of the brain no longer bothering to notice a smell.

IX. Its front foot; a porcupine’s back feet have five toes.