7

Down the Road

THE FIRST CLINIC I EVER DID was in 1983 in Four Corners, Montana, at an indoor arena owned by Barbara Parkening, the wife of Christopher Parkening, the famous classical guitarist. She had a little group of four or five lady friends who all rode together. I’d started a couple of colts for Barbara’s brother-in-law, Perry, and he had been trying to get me to give them a horsemanship class.

As this point in my life I was really shy about talking to people in public. I didn’t mind performing—my rope-tricks career proved that—but I didn’t feel comfortable speaking to groups. Even when I was riding colts, I didn’t like people coming around and watching me. They made me nervous. I didn’t want the social interaction because it scared me. All I wanted was to be left alone with a pen full of horses.

Perry kept encouraging me, telling me that I had a lot to offer and that I’d do fine in a public situation. I had gotten to know and trust him, so finally I offered him a deal. “All right,” I said, “I need maybe a dozen people to make it work. If you get everything lined up, if you make all the arrangements, collect all the money and rent the indoor arena, I’ll do the clinic.” I figured that if I gave Perry all of the responsibility and I didn’t take any interest at all in the deal, he’d just forget about it.

That’s not what happened. Perry came back a week later with the news that he had the people signed up, he’d collected the money, and he’d rented the arena I wanted.

Since Perry had done what I’d asked him to do, I had to be good to my word. I showed up and put on a clinic, but to be honest, I don’t know if anybody learned anything. I did what many people do when they first get in the teaching business: I tried to sound as much like the teachers I’d had as I could, parroting things that I’d heard over the years.

That’s because I had more confidence in my teachers than I had in myself. I couldn’t consider myself an authority, someone with anything to offer, when I’d never done something like this before. I was so unsure of myself speaking to a group of people, let alone teaching them, that I really don’t know if they learned anything.

When the clinic was over, a little gray Arab was still in his trailer. One of the students had loaded him because she’d wanted to ride him, but she couldn’t get him to back out.

I often tell people that if they can’t get a horse to back up on the end of a lead rope in the open, they may have a little difficulty getting him to back out of a trailer. A lot of times a horse would rather flip over than step down into the unknown.

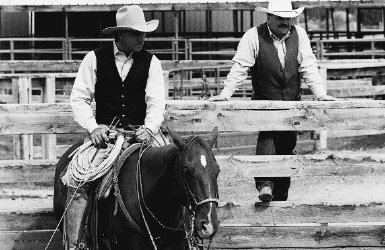

One of Buck’s greatest pleasures is to put on clinics with the friends who were there for him when he started his career. Here Buck engages a crowd in Billings, Montana, at a clinic sponsored by his friend and saddler, Chas Weldon (standing at right).

The horse was terrified to come out. I did the best I could to get him to step six inches back, then step a foot or two forward and another foot back. This was to help him gain some confidence moving forward and back in the trailer before he stepped down.

It wasn’t easy, but I finally got him out of the trailer. He didn’t hurt himself, but he could have. Then I explained to the woman the mistake she had made in the first place. Rather than loading her horse all the way into the trailer before she was sure she could get him out, she should have had him step carefully into the trailer with his front feet, then had him back up while his hind feet were still on the ground. Doing this procedure a few times would have given him the confidence he needed to back out once he was loaded.

If you ever make the mistake of loading a horse into a trailer without having taught him to back up, the best thing to do is park your truck and trailer inside a corral, leave the back door of the trailer open, shut the corral gate, and go to bed. During the night, the horse will get it worked out. He’ll come out. That’s the lowest-risk way of getting him out of the trailer.

Or, if you’ve got just one horse loaded in a two-horse trailer, you could remove the dividers. Even though it’s a pretty cramped space, you can often encourage the horse to turn around.

Many people consider loading horses into a trailer as something akin to having open-heart surgery. They know they need to do it, but they’ll do everything in their power to avoid it. That’s because they don’t understand what loading is really all about. It’s really quite simple, though: if a horse leads well, if he walks with you wherever you wish to go, he’ll load well. It’s an act of trust between two beings.

At a clinic in California a few years ago, a lady hired me to do a trailer-loading demonstration with her horse. A couple of handlers walked him down to the arena where I was waiting. Then someone drove her trailer up. A few minutes later, the owner herself showed up driving a Rolls-Royce. She stepped out of it and said, “Mr. Brannaman, I’m the owner of this horse, and I’m the one paying you to trailer-load him. I understand your fee is one hundred dollars. If you’re able to load him without too much trouble, I want to make sure I get a discount.”

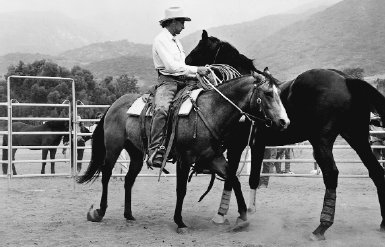

No horse is a problem horse; there are only problem people. Of the more than ten thousand horses Buck has started in his clinic career, he has never failed a horse. Here he starts a big warm-blood in Malibu, California.

The hackles on the back of my neck raised a bit. Here the woman drives up in a two-hundred-thousand-dollar car, and she’s worried about not getting her hundred dollars’ worth (if the stories I’d heard about her own trailer-loading expertise were true, she’d never find a vet to stitch her horse up for any less than that).

I said, “Ma’am, if you don’t feel like you got your money’s worth by the time I’m done, then you don’t owe me anything.”

I started the horse on the end of the halter rope, shaking the rope just enough to get the horse to move his feet back. I was being as subtle as I possibly could, trying to offer him a good deal. When I didn’t get the movement I wanted, I got a little more active with the rope until the discomfort of the swing caused him to back up. The effect of the rope wasn’t a lot different from a big horsefly buzzing around his head. The rope made him drop his head and back up, the same way a horsefly would.

Once I laid the foundation of getting the horse to move his feet, I could back him just about anywhere I wanted him to go. After just a little while, he was backing very nicely on the end of a sixty-foot rope. I then fed out the rope’s coils and backed him up the ramp and into the trailer. His hind end was all the way in the manger and his head hung out the back door. I even got him to where he would start beside the driver’s window of the pickup, walk down alongside the truck and trailer, turn the corner, and back up the ramp on his own.

That’s when I put the halter back on the horse and handed him to his owner. “There you go, ma’am,” I told her. “I’ve finished with your horse.”

Her eyes bugged out so far you could have knocked them off with a stick. “You never loaded my horse.”

“Oh, yes I did, ma’am,” I replied and turned around to the crowd. “Did I not load this lady’s horse?” Everyone confirmed that I sure had.

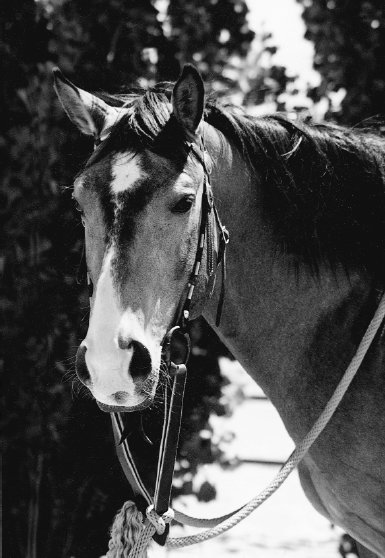

Buck’s little buckskin gelding, Cinch, has traveled with Buck over the years and become almost as well known as Buck himself. Cinch is retired today on Buck’s ranch in Sheridan.

She said, “Well, yes, you loaded him, but you loaded him backward.”

I put a puzzled look on my face. “Well, ma’am, you didn’t say which way you were looking for me to load him, so I don’t know how I was supposed to know.” With that, I reached into my pocket and gave her back her check. “You have a good trip home, ma’am. I hope everything goes fine for you and your horse.”

The last thing I saw at the end of the day was the horse on his way out of the arena, his butt in the manger and his head hanging out the back of the trailer. As he went out the gate, he whinnied at me as if to say, “Well, thanks. It wasn’t really what I expected, but I’m in anyway.”

The last I heard, that lady was successfully loading her horse on her own. She was still loading him backward, but she was loading him, nevertheless.

It’s kind of like the old saying: Be careful what you ask for; you just may get it.

Loading wouldn’t be a problem if leading weren’t a problem. I wish I had a dime for every horse I see either dragging his owner along at the end of a lead rope or else being dragged. Or make a right turn by being turned to the left three times. You’d think the person would be embarrassed to death, but he’s not. I know I would be.

Problems with leading happen because the basic groundwork is lacking. A horse that has learned to hook on to a human and to free up his feet will follow the person calmly and willingly.

One thing, though: People often lead from the wrong place. They walk either directly in front of the horse or back at the hip. Both spots are blind spots where the horse just can’t see you, so no wonder he’ll run over the top of you or swing into you and knock you flat. Try to be enough to the side and ahead so he can see you. You should be able to make a right turn and not run over the horse to get there.

And speaking of embarrassment, I can’t imagine why people who have to stand on a box to get a halter or bridle on their horse’s head aren’t mortified to let others see them do it. Any horse that can reach down to graze—and that would be every horse—should be able to lower his head so even the shortest person can put on a halter or bridle.

That’s why when I start working with young horses or help older troubled ones, I always rub them along on the neck and around the ears. Comforting and supportive touching around the head means a great deal to them. They’ll welcome it and put their heads down for more, even when you have a halter or bridle in your hand.

I also make sure that I don’t slam a bit into their mouths. That’s a quick way to make a horse head shy.

Okay, one more point in this area: A horse that walks off while the rider is stepping on is a reflection of the owner’s weak horsemanship. It puts the rider in a precarious position, and it shows that the rider has lost control. All my horses stand while I mount, and they don’t move off unless and until I ask, even if they see other horses moving around. My horses listen to their rider, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Nor do my horses leave me when I turn them out in a paddock or pasture. They stand quietly while I remove their halters, and they continue to stand while I leave them. That is, I walk away from them and not the other way around. That way, there’s never any spinning around and kicking out, so nobody gets hurt.

Early in my teaching career, I gave a summertime clinic in Scottsdale, Arizona. It was 117 degrees, and the dust in the arena was like flour. Nowadays I wouldn’t put horses or people through that torture, but we all suffered along. So did the arena crew, who did the best they could to keep the footing watered.

The horsemanship class had about forty people trotting around on their horses in the dust. The sun was blazing, and about halfway through the class, I suggested that everyone take a break for a few minutes.

One fellow in the class was nicknamed Polack. I felt embarrassed calling him that, but he wouldn’t answer to his real name. He liked his nickname; he apparently was quite proud of his Polish heritage. Polack had a sorrel horse that was a little on the volatile side, kind of a hand grenade with a saddle strapped on.

When we took the break, Polack rode up to the edge of the arena with the others, stopped at the fence, hooked a leg over his saddle horn, and tipped his hat back, just like the Marlboro Man posing for a cigarette ad. His wife handed him a container of water, a plastic milk jug with ice in it.

When Polack tipped that jug up and took a big slug of water, the ice hit the bottom of the jug. The young sorrel spun around and left, hell-bent for election. Polack still had his leg hooked over the saddle horn and his hat tipped back, and he was still holding on to this jug. Even though realization and terror overtook him, he couldn’t seem to let go of the jug. Having seen a similar move with Ayatollah and my coat, I felt “the pain of my brother.”

His horse was at a full gallop now, a red blur across the arena. I quickly turned on my microphone and pleaded, “Drop the jug! Polack, drop the jug! Please, please drop the jug!” I repeated my plea again and again as he went down the arena, which was about three hundred feet long and surrounded by a fence made of stout two-inch steel pipe.

Just as he raced by me, the light came on. He looked down at his hand and the idea seemed to register on Polack’s face. He dropped the jug. But his horse was still at a full gallop, and even though Polack had dropped the jug, they were so close to that pipe fence, I was sure that he had failed to save himself.

It was my first real heavy year of doing clinics, and there I was in the middle of a boiling arena, dust everywhere, and my first fatality was about to happen. As I prepared for the wreck of the century, both Polack and his horse disappeared in the dust.

A miniature mushroom cloud boiled up over the arena. Then, as the dust slowly began to settle, I just about fell over. I felt like one of those cartoon characters with buggy eyes on big springs.

There was Polack—still on his horse, his leg still hooked over his horn, his hat still tipped back on his head. His horse had made a perfect sliding stop, ending with no more than a quarter inch to spare in front of the fencing. The track on the dusty surface of that arena was the most perfect parallel-lined “eleven” I’d seen in a long time.

Polack turned around and looked at me and said, “Yahoo!” The crowd erupted in applause.

After that averted mess that day, I told Polack he was welcome to stay, but with the kind of luck he had, he really didn’t need me. The last I heard, he was still alive and well somewhere in Arizona. I hope his luck holds out for him.

I’ve heard a lot of people say they’d rather be lucky than good, but not me.

Mike Thomas, a friend who had managed the Madison River Cattle Company before he tired of the Montana winters and moved down to Arizona, set up a clinic for me at the Mohawk arena in Scottsdale. We had quite a large group of people, and as it happened, the manager of an Arabian horse ranch that had canceled one of my clinics the year before was one of them.

I was doing a trailer-loading demonstration on a little Appaloosa mare, leading her off my left shoulder from right to left and getting her to lead past me while I stood still. Once I had her going smooth and could stop her on the lead rope and then get her to step back, we moved to the trailer, where I started loading her and backing her out.

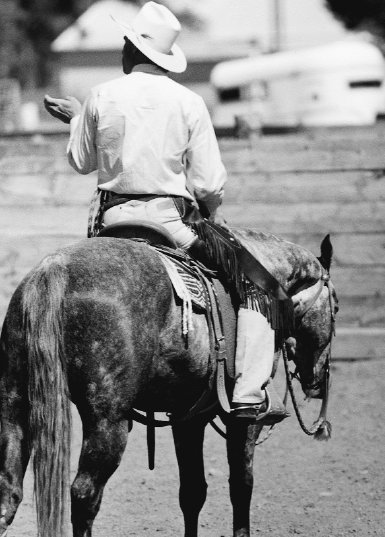

Buck on his saddle horse Jack, answering questions at a clinic. Question-and-answer sessions at Buck’s clinics last as long as they last—sometimes long after the sun goes down.

Each time I prepared to load the mare, I’d give her a little more rope and step farther away, thus widening the gap between the trailer and me. If she chose to go through the gap rather than into the trailer, I’d take a step forward and divert her into it. If I hadn’t and she had gotten used to going between me and the trailer, it would have been the equivalent of letting her run me over.

Once the mare was confident loading that way, I worked my way up to the left rear of the trailer. I began loading her on an even longer rope, moving her in an arc from my right to my left. I’d pet her and reassure her, back her out again, play out a little more rope, and lengthen the arc. After a little while, I was standing by the tandem wheel so I was out of her sight when she loaded.

By the time I was able to stand by the truck’s side mirror, I had to replace her halter with a thin nylon rope around her neck. The mare was real responsive now, and since she was on forty to fifty feet of rope, anything heavier than the nylon would have made her turn and face me.

I finally got the mare to the point where I could sit in the front seat of the truck and feed coils off the rope out the side window. The mare promptly went to the trailer and loaded, which seemed to really impress the folks at the clinic.

At the end of the day, the manager of the Arabian outfit came up to me. He was very excited about what he had just seen. He said he had an expensive Arab stud that had never had a successful trailer ride, and he asked me if I would load him.

I hadn’t forgotten that the manager worked for the folks who had betrayed my trust and put me in a bad spot by canceling that clinic. So I said, “Okay, it’ll cost you five hundred dollars.” In those days I charged a hundred dollars to load a horse, and this was my way of telling him to go to hell.

He didn’t even blink. Instead he asked, “When can you show up?”

I wished I’d asked for five thousand, but I had to be good to my word. The next day after I’d finished my clinic, I drove to the fellow’s farm. I figured I needed to get the horse pretty well trained for that kind of money, but I got him loading into the trailer without much of a problem. In fact, I got that stud horse to the point where, turned loose beside a pen of mares, he’d walk away from them and get in the trailer.

One person watching this demonstration was a local used-car salesman who had married into a very wealthy family. He was running off at the mouth with some of the other spectators, and I heard him say, “I bet Brannaman couldn’t load our horse.”

His wife, who had ridden in one of my public clinics and was interested in my kind of horsemanship, said, “Well, honey, I’ll bet you a thousand dollars he can.” Then she asked me, “Buck, would you be interested in going partners on this?”

I jumped at the opportunity. “Bring him on.”

Their horse was a famous Arab halter show horse imported from Europe for more than a million dollars. In those days when a horse needed to show spirit to win a halter class, in which animation seemed to matter as much as proper conformation did, many trainers and judges confused “spirit” with terror. In order to get the right expression, some trainers kept their horses in tiny stalls and ambushed them in the dark with fire extinguishers so that any sound would provoke a terrified “look of excitement.” Another favorite trick was to cross-tie a horse in water and hook electrodes to his neck so that he’d tense up when they hit the switch.

That kind of terror tactics had gotten this horse to the point where he was unsafe to work with or just to be around. His stall door had a double padlock so no one would accidentally walk in on him. His owners had catwalks installed on both sides of his stall. To get him to me, his handlers climbed up on them and used long poles with hooks at the ends to grab his halter. Once they had the horse more or less under control, they chained him from both sides and muscled him into a rented semitrailer. It was no easy job, and it took several hours.

When they got to their destination, the handlers had to use their chains to bring the horse into a small arena surrounded by a low fence. When he immediately broke free and began racing around the arena, I saw how dangerous he was. He wore a halter with a chain shank over his nose, and I could tell that he’d had it on for some time because his nose was terribly scarred.

I entered the arena riding my saddle horse. If I’d come in on foot, he would have attacked me. My first job was to get a rope around his neck so I could control his feet. The fence was so low, if I roped him when he was in a corner, there was a good chance he’d jump the fence and break a leg. Plus, if I missed my shot and he jumped out, he would find himself in the middle of one of the busiest roads in Scottsdale. Neither of the prospects was anything I wanted to think about. Aside from the danger to the horse, I wasn’t in any position to pay for my mistakes in those days.

After some fifteen minutes, the horse finally moved to the middle of the arena. The roping gods must have been with me, because I roped him around his neck and got him stopped. However, now I had to keep him at the end of my sixty-foot rope, because any closer and he would have crawled up in the saddle with me.

I worked with him the same way I would work a horse I was teaching to lead, getting him to “turn loose” to me. Occasionally, this horse would give to the rope and put some slack in it. However, feeling any pull caused him to immediately begin ducking his head and thrashing around as if to avoid an imaginary whip. He even got down on his knees, laying his head on the ground and closing his eyes as though having a recurring nightmare of past abuse. To imagine what this horse had been through was painful.

After a lot of sweat and tears for that little horse, I was able—after an hour or more—to bring him close enough that I could slip the halter and shank off without being bitten.

Reaching across my saddle horse, I placed my hands over the Arab’s nose and rubbed him where he’d been chafed for so many weeks. His response was to lay his head across my leg up on the saddle and close his eyes. He may not have felt this safe since he’d been with his mother. He’d finally met a human who knew how to be his friend.

He and my horse walked around the small arena, his head still in my lap. There was salt on my chaps from rubbing up against many sweaty horses, so when we would stop, the stallion would affectionately lick my chaps. When I put my hands in his mouth around his lips, he gave me no trouble. He wasn’t defensive. He had no plans to strike me, bite me, kick me, or even to leave me.

The Arab was leading well, so at this point I felt safe enough to step off my saddle horse and approach the horse trailer. I was now ready to begin what I had been hired to do, although most of my work had already been done.

Getting the horse to load didn’t take very long because we had become partners. I could steer him into the trailer by his tail; I could even pick up three tail hairs and back him out of the trailer without breaking one of them.

The horse became so quiet and relaxed, some in the crowd began to worry that he couldn’t win a halter class looking the way he did—without the look of terror that’s often confused with what they think is “spirit.” Hearing them say that made me realize how hard it was to understand how seeing a horse in a relaxed frame of mind could be any cause for worry. These people were as different from me as any people I’d ever met.

As the little horse stood quietly with his head in my arms, a lady in the crowd who owned a local Arabian farm of her own spoke up. “Buck, now that you’ve gotten this horse coming around the way you have, when would we be able to start with the whips again? Would we be able to start tomorrow, or would we have to wait till next week?”

She had no idea what she was saying. It was the most bizarre thing I’d ever heard, and from a woman who appeared to be so sophisticated. How could she say something so uncivilized?

I couldn’t take it, not after what the little horse been through. “Some of you can go to church on Sunday and claim to be holier than thou, but the other six days of the week you’re torturing horses and committing crimes against them. You make me ashamed to be a human being.”

But that wasn’t all that bothered me. That little horse had made a friend that day. He appreciated what I had done with him—I know he did. Yet I went away with a sick feeling, wondering if maybe I had done wrong. On one hand, I had helped him, but I had also shown him there was something truly good in life that he would always miss.

I later learned that he went back to his same life. In that world of barbarians, defense was his only means of survival, and I worried that I might have taken it away from him.

Even years later, I still wonder if he remembered me, the man in the cowboy hat who for just a few hours had been his friend.

You wonder what a horse knows and how deep it runs.

My brother-in-law, Roland Moore, is a good cowboy. Roland married the Shirleys’ daughter Elaine, and was working as a cowboy on The Flying D ranch. When we first met I was only twelve and he was twenty-eight, so due to the age difference, our friendship didn’t amount to much at first. I saw him off and on, but it wasn’t until I was a little older that we started riding and working cattle together.

When Forrest and Betsy were ready to retire, Roland and Elaine moved in and took over the place. It’s called the Cold Springs Ranch now, and they all ran it together until Elaine died in 1999. The Flying D and Spanish Creek have since been sold to media mogul Ted Turner, who started a buffalo-raising operation there.

Roland and I were out on horseback one day after I had started competing in high school rodeos. He looked over at my horse and said, “You know, there’s a difference between a rodeo cowboy and a working cowboy. Working cowboys don’t use tie-downs or draw reins or any of those gimmicks on their horses.”

He was right, of course. I was still a kid and didn’t realize that using restrictive tie-downs in rough country could be dangerous: a horse that wore one and then stumbled and fell could have difficulty getting his head back up to regain his balance.

During the winter of 1988 when I was in Florida playing polo, Roland called me up. He had acquired a new horse, a palomino named Tony that was a brother to my horse Bif.

According to Roland, Tony was very broncy. “He bucked me off at this branding, and I landed on the back of my head. It felt like he almost broke my neck. I’m going to get rid of him. What do you think about that?”

Now, Roland was about as subtle as a pool cue in a pencil box. I knew he was fishing for me to validate his decision, so I said, “You know, you’re probably right, Roland. You don’t need a horse like that around.”

Roland was real quiet on the other end of the line, so I paused a second and asked, “Do you think it’ll ever cross your mind that maybe there was something in that horse you missed? That there’s something that you miss on a lot of horses, and maybe it’ll come up again, and you’ll have the same thing happen, and have to get rid of another horse?”

Roland still didn’t say anything, so I went on. “Ah, you know, really, on second thought, you probably should just get rid of him, and don’t worry about it. It probably won’t come up again.” We visited a little bit, and I hung up.

After I got back to Montana that spring, Roland called again. “Hey, I still have that palomino. There’s a horse sale coming up in town, and I thought I’d run him through there. But before I do, maybe I’ll come by, if you don’t mind, and you could have a look at him. Maybe you could tell me what I missed on him. Then I’ll go ahead and get rid of him.”

I told Roland to come along, and it was pretty clear when we saddled the horse that he had missed some basic groundwork. There were plenty of things Tony couldn’t do with his feet because they weren’t freed up. As a result, he was having trouble moving his hindquarters to his right. He should have been able to distribute his weight evenly on all four quarters while moving forward or back, but he couldn’t. These movements are basic dance steps that a horse learns at the end of a lead rope, and if he can’t do them, there’s a very good chance he’s going to buck somebody off.

I worked with Tony from the back of my saddle horse for a while until his feet were well freed up. Then I told Roland to get on.

Roland looked over at me like he’d swallowed a fly. “You know, the last time he really bucked me off.”

This was coming from a good cowboy who has worked on some of the biggest outfits in the country. Tony had really chilled him.

I said, “Roland, you came by for this moment. You really wanted to know or you wouldn’t have kept Tony this long. You’ve got to trust me here—I wouldn’t try to get you hurt.”

I was sitting in the middle of the round corral on my saddle horse holding on to the end of the lead rope. I had Tony pointed off so he could take a right circle.

Roland swallowed real hard, but he got on. When I told him to move Tony right on up to the lope, he looked at me and said, “That’s where he got me—loping him off on a right lead.”

“He’s all right, Roland,” I reassured. “He’s all right. Trust me.”

To Roland’s credit, he did. Tony responded to his cue by loping off into the prettiest circle you’ve ever seen. After a minute or so, Roland relaxed and realized he wasn’t going to die. He looked bewildered. He didn’t say anything, but his eyes were asking, Why am I still alive?

When he finally stepped off Tony, Roland was buzzed. All he wanted to do was talk about it. I stopped him and said, “You know, Roland, we’ll have to talk about this some other time, or you’re going to miss your horse sale. I don’t want to make you late.”

Roland headed off to town. He was happy, confused, relieved, and exhausted, and I wasn’t surprised when I learned he didn’t sell the horse.

Tony was a turning point for Roland. For all the experience that he’d had, Roland had decided to become a student again. Since then, he’s worked with lots of horses. He’s had his ups and downs, but he worked at it and today he’s a true student of the horse.

There are two happy endings to this story: Right now Roland is one of the best hands around. Guys who used to think their abilities were on the same level as Roland’s got left behind years ago. Some of the people who were once his equals couldn’t saddle his horse now.

And Tony? Tony ended up a bridle horse at Cold Springs, one of the best bridle horses you’ve ever seen. In our circle that means Tony is what is called “straight up in the bridle.” He’s a fine horse and a true pleasure for anyone to ride. He will live life to the fullest with Roland. In my world, any horseman who can bring a horse to that level is to be highly exalted.

I’ve been giving clinics for almost twenty years now, and I’ve seen some pretty odd things and worked with some pretty odd people. The bunch I had at a clinic near Buckeye, Arizona, was one of the strangest. Some of them were bikers, while the others didn’t appear to spend a whole lot of time in town. They looked like desert dwellers to me; I don’t know what else to call them. None of them looked like horse people.

By nine o’clock in the morning, while I was trying to help them work with their colts, they sat around dressed in black leather and drinking beer. My teaching isn’t real formal, but my clinics are normally taken a little more seriously than they were taking this one. They were all attentive, and they were eager enough, but it seemed as if what they mostly wanted to do was party.

Nonetheless, some of their horses were nice and gentle. One little two-year-old filly was a cupcake, but by the way she tiptoed around, I could tell that she was pretty scared. Not wild, but just scared. She hadn’t been handled a lot, so she scooted around the corral the way a lot of youngsters will do to avoid being with you.

When the filly’s owner identified herself, I saw what the little horse was bothered about. The owner was a woman in her twenties, and if she didn’t outweigh the horse, she came close. I can often guess a person’s size just by looking at the size of the saddle on the horse, but in this case the two were nowhere close.

The woman walked over to the filly, whose eyes grew big as saucers. The stirrups were only about a foot and a half off the ground, but the woman couldn’t put her foot in without just about tipping the little horse over sideways.

“Why don’t you get up on the fence,” I suggested, “and I’ll see if I can teach the horse to pick you up from there.”

She couldn’t do it—she literally could not get up on the fence. Some of the spectators who saw her dilemma came over to help. They pushed while the woman pulled, until eventually she was perched precariously on the top rail.

I led the filly over and said, “I just want you to get her used to you. I want you to pet her. Rub her and reassure her and get her used to seeing you from up above. Then once she gets a little more comfortable, I want you to s-l-o-w-l-y slide down on her and get settled. Then I’ll lead you around, and we’ll take you for a little ride.”

The average person would understand my meaning: Take your time—I’ll let you know when to get on. Not so this gal. She either flew or fell off that top rail. Either way, she angled a leg over the top of the saddle, dove at that horse, and plopped down on her back.

The poor little filly was practically bowed under by this sudden added weight. But she stood there and looked up at me as if to ask, What in the world just landed on my back?

The woman looked terrified. “You’re going to be all right,” I told her. “It looks to me like you haven’t ridden too many colts, so you just rub on her and I’ll hang on to the lead rope and help you get through this.”

The woman stared at me. “Haven’t rode many colts? Hell, this is my first time on a horse.”

You can imagine my surprise. I figured I would have to pull a miracle out of an unmentionable place, but that little filly did the job for all of us. I got on my saddle horse and led her around. The filly stayed right underneath that woman, licking her lips with contentment and doing just fine.

Since everything was looking pretty good, I moved the filly up to a trot. My horse had a longer stride, and I wanted the filly to step out and catch up, but the minute the pace increased, the woman panicked. She bailed off and tried to dive for the fence, but her aim was off, and when she hit the ground, she rolled under her horse.

I didn’t know what to do. I couldn’t back the horse, and I couldn’t lead her forward without the woman being stepped on. All I could see was a wreck ahead.

The filly knew full well that we were all in a bad spot. She just looked down, lifted a hind leg to step over the woman, then lifted the other hind leg and stepped over again. I couldn’t believe how high she lifted those legs. The filly never even touched the woman. Once she was clear, she walked on by with as happy an expression as I’ve ever seen on a horse.

The woman stood up, brushed herself off, looked at me, and said, “Well, that’s not too bad for the first ride, is it?”

What could I say? I came up with, “No, that’s not too bad for the first ride, but if it’s all right with you, maybe you could take a little break and I’ll have another rider get on and finish up.”

She agreed, relief filling her face. I felt the same way myself. Things worked out fine, and before the clinic was over, the lady was back on her filly and doing okay.

I’ve often told people who ask if there is a God: “Get around enough people with horses and see what happens. See how they survive in spite of all the things that they do, and you’ll become a believer!”

At another clinic, this one in Ellensburg, Washington, a student came with a colt that needed some preliminary work. In those days I charged an extra hundred dollars for horses that weren’t halterbroken. If they were real tough to work with, I’d give the owners a hand so they didn’t have to do all the work themselves.

This horse was wearing a halter when he got out of the trailer, but he was troubled. By the time the other students were saddled up, his owner still couldn’t get near him. The colt was pulling away and showing a lot of resistance at the end of the lead rope, the kind of behavior that generally doesn’t occur with a horse that has never been handled. Since he was wearing a halter, it was obvious that somebody had tried to start him and failed. He had cuts, nicks, and scars on his body, too.

I told the owner, “Take your halter off and borrow one of mine. Your lead rope’s so long, you’re going to get in trouble with it. So put mine on him, and then just go up and pet him.”

He replied, “I can’t get to this horse. He’s going to strike.”

When I asked how he got the halter on, the owner lied, “Well, we didn’t have any problem at home.” It was obvious the guy was just biding his time until I took over; he wasn’t about to get close to that horse.

The colt really was dangerous, so we ran him into the round corral, and I roped him from my saddle horse. He would strike at my horse, but we stayed out of his way and after I worked with him quite a while, I roped a hind foot. Although the colt gave to the pressure of the rope, I knew that he would kick, so I had my horse hold him by a hind foot so that he couldn’t get his hind leg forward.

That’s how I saddled him. Once the cinch was tight, the colt bucked quite a bit. He’d had experience at arranging his body in a way that he could get the most leverage when he tried to get away. That’s how I could tell somebody had worked with him; he was looking for certain actions from me that he had experienced at the hands of somebody else. When I’d start to approach him, he’d position himself so that he could kick out with his hind legs or rear up and strike.

I felt really sorry for him, and I wanted him to get through this day just as easy as he could. I slipped my halter on him, let my rope drop off his hind foot, and told him, “You know, big fellow, I’m going to just get you rode the best way I can, and then put you out for the day.”

I was going to lead him by me just once or twice, get him to break over his hindquarters, and then I’d step up on him. But when I asked him to lead by, he evidently saw me do something that the people who had tortured him had done.

I’m afraid I had let my guard down. The colt reared up on his hind legs, struck out at me, and pawed me to the ground. He had me down between his front legs, and then he leaned down and started biting and chewing on me.

I rolled up in a ball and just tried not to move. A couple of friends were watching, and they told me later they were getting a little concerned. They said it looked as if I was getting into trouble, and they thought they were going to have to jump over the fence and drive that horse off me. At the time I remember looking their way and thinking, Just how bad does this have to get, fellas?

Anyway, I fared surprisingly well. Once up, I got the colt caught again and tried once more. I thought I’d gotten too far ahead of his shoulder the last time, so I stepped a little farther back and tried to lead him again, but I still hadn’t learned. The colt got the drop on me again, whirled away, and had me lined up for a kick.

At this point the best I could come up with was to move right into his tail so all he could do was kind of bump me. That’s a good thing to know: The closer you stand to a kicking horse, the less impact the kick will have on you.

I stepped in so the colt couldn’t really kick me, but he knocked me down again. His owners had turned this poor horse into a predator. He was no longer a herd animal—he was the hunter, not the hunted. I told myself, “You know, Buck, keep this approach up, and there’s not going to be much left of you.”

I got back on my saddle horse, roped one of the colt’s hind feet again, and worked with him some more. Once the colt knew I had the upper hand and he couldn’t get to me, he just lay down on the ground—he “sulled up” with frustration the way a spoiled kid does when he lies down on the floor—and he wouldn’t move.

I got off my horse while the colt was still down, and as I was getting ready to pull my rope off his hind foot, he rolled an eye back, looked at me, lifted a hind leg, and kicked me right in the middle of the thigh. Then he lay flat again. He was really something.

The benefit of the doubt I’d been giving him was now completely used up. He was still down on his side, and I muttered, “Horse, there is nothing you can do to me while I’m sitting on your back that you haven’t already done to me on the ground.” I couldn’t wait to get on him. I laid a leg over the top of him, just as you saw Tom Booker do in the movie The Horse Whisperer, except this wasn’t a gentle horse, and we weren’t in a movie.

I rocked the colt up and pulled on the saddle horn. He tried to reach around and bite me while he was still lying down, but I was able to get my leg out of the way. When I nudged him in the ribs with my foot, he got up and off we rode.

It wasn’t too long before I had him loping around and being guided pretty well. Within a half hour he found out I was different from the man who brought him. Before the morning was out, he and I were roping colts and moving other horses around. He was operating like a saddle horse. We were on our way.

I later found out his owner used a “hot shot” cattle prod to run him into a metal squeeze chute. Then, while clamped in the chute, the horse had a halter forced on him, after which he was spooked into the horse trailer the same way you’d load a cow. The squeeze chute was how he’d gotten so skinned up. It seemed the owner’s plan was to save the extra hundred dollars I charged for horses that weren’t halterbroken, and at the same time see how much trouble he could get me into.

The next morning the owner arrived with a different horse. “I want you to know that I’m not scared of that horse I brought here yesterday,” he assured me. “I just thought I’d learn a lot more from you if I brought a colt I’d already rode a few times. I won’t have any problem getting that other horse rode at home. Because like I told you, I’m not scared.”

“That’s fine,” I replied. “But what you don’t realize is that with what I accomplished on your horse yesterday, you could have ridden him today. But you go ahead and ride that colt you brought. That ought to be just fine.”

He got his second colt saddled up and ready to go. Everyone else in the class was putting a first ride on their colts. When he got on, his colt didn’t put up with him for two minutes before he bucked him off on his head. I call that frontier justice. The guy eventually did get the horse ridden and finished out the clinic, but he didn’t make many friends that weekend.

I remember that horse quite often because the experience did sharpen me up. I felt so much sympathy for the abuse and torture he’d suffered before he came to the clinic that I tried to do the minimum. What I did helping him come out the other side was not enough for him and certainly not enough for me. To be honest with you, with the kind of owner he had, I don’t think that horse survived.

I’ve worked with similar horses that went away in the same condition, and it always makes me wish I was in a place where I could save every one of them. At the same time, I learned a lot from them, and a lot of people learned from them as well, so maybe it was worth it in the long run.

As I said, I’ve thought fondly of that horse lots of times. The best I can do is honor his life by using what I learned from him to help others.