MAGIC LANTERN SHOWS In the late 1800s—before the invention of motion pictures or slide presentations—people were fascinated by magic lantern shows. These were simply exhibitions of images projected onto walls by means of a simple light source. Showmen would illuminate painted glass panels, silhouettes, or shadow figures from behind, creating glowing pictures. In the hands of industrious ministers, this technology became a popular means of graphically illustrating HELLFIRE SERMONS.

Victorian era drawing of children enjoying a magic lantern show. ART TODAY

The most effective method was to place two disks, each painted with splashy yellow and orange flames, together in the lantern. As the preacher spoke of FIRE AND BRIMSTONE, he slowly rotated the disks in opposite directions. This created a powerful and frightening image of a blazing inferno. The illusion was often enhanced by stenciling in the figure of a man. By gently shaking this disk, the image seemed to depict a condemned soul languishing in the raging fires of hell. After witnessing this disturbing vision, many hardened sinners were converted to Christianity.

Magic lantern shows, and their religious usage, died out around the turn of the century, when photography and then motion pictures captured society’s collective imagination and rendered them obsolete.

MAGICIAN JAMES An illustration from an eleventh-century Anglo-Saxon manuscript titled Magician James depicts the grim underworld of medieval tradition. The picture shows the bodies of the damned smoldering as they burn with unquenchable fire. As they writhe in agony, snakes strike at their faces and coil around their bodies, crushing them. The DEVIL oversees this torture. He is portrayed as a humanlike creature with horribly bloated hands and long, sharp nails. His face is a grotesque mask of withered skin, piercing teeth, and haunted eyes.

The work represents the prevailing view of CHRISTIAN HELL during the Middle Ages: a horrific subterranean dungeon of brutal punishments and unrelenting agony. It also alludes to the coming rash of witch trials, which linked the magic arts to SATAN, FAIRIES, and hell.

MALIK Malik is the DEMON who rules JAHANNAM, Islamic hell. He is also responsible for bringing the souls of evil people to the underworld. The KORAN states that sinners often beg Malik to intercede for them; however, he offers no comfort. He will be silent until a millennium after the LAST JUDGMENT, at which time he will taunt sinners, declaring that their damnation is eternal.

MAMBRES The legend of Mambres dates back to the medieval days of Anglo-Saxon witchcraft. According to the tale, Mambres, grief-stricken over the death of his brother—who was reputed to be a dark wizard—uses a book of his brother’s spells to try to contact the dead man’s spirit. As he delivers the incantation, the jaws of hell open before him and Mambres’s brother appears. But the creature Mambres sees is not the brother he remembers but rather a huge, hairy monster with his brother’s face. The giant is feeding on the damned, chewing souls as they writhe in agony. Horrified, Mambres casts the spell book into hell and swears never to use magic again.

As he does this, the mouth of hell closes, and the grotesque mutation of his brother disappears. Mambres then runs off to the nearest church, where he vows upon his soul never again to dabble in the dark arts.

MAN AND SUPERMAN Man and Superman, written in 1905 by Irish dramatist George Bernard Shaw, offers an intriguing concept of hell, heaven, and the nature of suffering. In a dream interlude titled “DON JUAN in Hell,” Shaw depicts an afterlife where salvation and damnation are simply a matter of perspective. This notion, explored in depth by WILLIAM BLAKE, suggests that some souls would find paradise insufferably dull and would welcome condemnation to the feisty inferno.

Often called “a play within a play,” this portion of Man and Superman is frequently performed independently and has become a standard on the Broadway stage. But when “Don Juan in Hell” was first produced, many critics found Shaw’s interpretation of the afterlife offensive, even blasphemous, prompting some proprietors to demand that the author include a “disclaimer” in the show’s program. When London’s Royal Court Theatre presented the drama in 1907, management required that Shaw justify his unconventional work. His explanation, which was distributed to all patrons, decries “legends” of hell as “a place of cruelty and punishment.” To Shaw, the underworld is a realm “given wholly to pursuit of immediate individual pleasure” rather than a fiery torture chamber.

“Don Juan in Hell” has only four characters: legendary ladies’ man Don Juan; Dona Ana, an object of his infatuation; Don Gonzalo of Ulloa, Commandant of Calatrava, Ana’s father who was killed by Don Juan while defending his girl’s honor; and LUCIFER, lord of hell. The play opens as Don Juan, long a resident of hell, welcomes the aged Dona Ana to the afterlife. Horrified at the thought that she has been damned, Ana insists that she has been unfairly condemned. The two then discuss heaven and hell, a debate eventually joined by her father (who is visiting from paradise) and Lucifer himself.

What follows is an intricate dialogue in which heaven is derided as “dull and uncomfortable” and hell extolled as “the home of honor, duty, justice and the rest of the seven deadly virtues.” Don Juan notes that “all the wickedness on earth is done in their name.” Even the commandant (who has taken the form of his memorial statue) declares of the underworld that “the best people are here!” whereas the citizens of paradise are the “dullest dogs” of honor, “not beautiful, but decorated.” Before deciding to remain forever in hell’s “palace of pleasure,” the commandant admits that he fought for Ana not out of love or devotion but because it was his “duty,” and he worried that refusing to do so would sully his reputation.

Don Juan, on the other hand, is revealed as a man so thoroughly committed to finding the deeper meaning in life that he could not be satisfied with human love. It was this hunger for purpose and not carnal lust that caused him to go from woman to woman in a futile search for fulfillment. In hell, his desire for infinite knowledge is further frustrated. The Don laments that although he suffers no physical agony, the underworld “bores me beyond description, beyond belief.” In Shaw’s estimation, hell is a place of gratification, whereas heaven is a realm of contemplation. Meditation before the Almighty, a fate the superficial commandant finds unbearably tedious, would be ultimate bliss for Don Juan.

A similar analogy appears in AUCASSIN AND NICOLETTE, a French drama in which the star-crossed lovers vow they would rather suffer together in the depths of hell with other “interesting” heroes than languish in a celibate heaven filled with “dull” saints.

MANALA According to the myths of Finland-Ugaria, souls of the dead travel to Manala, the “land beneath the earth.” The passage to this underworld is at the mouth of a river that opens to an ocean of ice. Dead souls cross the river, then follow an enchanted bird to the gate of Manala. Unhappy spirits linger at the entrance, haunting rivers and lakes in protest of their fate. Manala’s ruler is Nga, an overseer who also controls the spirits that cause sickness and death.

Since Manala has no light of its own, the dead must take a spare sun or moon with them to the underworld. Those shapes are often engraved onto tombstones for the dead person’s use in the afterlife. Physically, the underworld is thought to be quite similar to the terrestrial plain, sharing the same plant life and geological features.

The dead are buried with their own clan in family cemeteries in the belief that the departed dwell directly under their tombs and want to remain close to their loved ones. In their new existence, inhabitants of Manala are vaguely aware of what is going on above them but cannot interact with the living. They survive on offerings of fruit, bread, and other foods brought to their graves by relatives.

Death is considered a transference to another state rather than a time of judgment, and residence in Manala is temporary. After a brief time lingering in this realm, souls die a “second death” when family members stop bringing offerings of food to the grave site. Spirits eventually fade completely (a version of ANNIHILATION), though many believe that departed souls can be reincarnated in the bodies of grandchildren and future generations.

MARDUK Marduk is the ancient Mesopotamian god of the underworld. He is an abominable beast associated with plagues and horrible deaths. In addition to abusing damned souls, Marduk can attack the living. He is considered particularly evil and sadistic among the dark deities of CHTHONIC lore.

MATEXZUNGUA Mythology of the Sioux of North America includes Matexzungua, the lord of the dead. Matexzungua lives in the north, in a place of insufferable cold and perpetual blizzards. His task is to torture the souls of evil people in his PURGATORIAL HELL. Once they have been cleansed of their wickedness, these spirits are allowed to journey to a tropical paradise located in the south.

MEDIEVAL DRAMA European drama took a four-hundred-year hiatus between 533 A.D., the date of the last public performance in Rome, until the tenth century, when Roman Catholic church officials began producing dramatizations of religious doctrines. These first performances were crude retellings of supernatural events such as the expulsion of LUCIFER from heaven, the HARROWING OF HELL, and the LAST JUDGMENT. Each different setting—heaven, hell, the Garden of Eden—was represented by a wooden booth, with actors moving from one to the next as the plot unfolded. Early medieval plays were strictly overseen by church officials, but by the late 1300s, most public dramas were produced by craft guilds dedicated to theatrical arts.

Some of the most powerful scenes in these dramas invoked images of the underworld. In Fall of Lucifer, the DEVIL declares, “I make my way to Hell to be thrust into torment without end!” The villain of an early passion play introduces himself to the audience with, “I am your Lord Lucifer that came out of Hell! I am called SATAN!” Another play of the period shows Judas writhing in infernal torment for betraying Christ. Such graphic portrayals of the inferno became progressively more horrific and complex as audiences grew and staging techniques evolved.

As the plays became less a province of the church and more an entertainment form, texts strayed from literal biblical interpretations to more speculative treatments of the supernatural. Depictions of the Antichrist and of the horrors of hell became the biggest crowd pleasers. Innovative set designers constructed the theatrical HELL-MOUTH, a trapdoor that opened from below to spew fireworks, noxious fumes, and horrible sound effects, to further tantalize audiences and boost attendance.

The resurgence in popularity of public performances eventually branched off into several different areas. MYSTERY PLAYS treated aspects of the supernatural but with increasing emphasis on the occult, FAIRIES, and other subjects frowned on by church hierarchy. Christian authorities began funneling their efforts into MORALITY PLAYS, dramas that adhered strictly to the teachings and events of the Bible. FOLK PLAYS, a less polished version of theater, also became increasingly popular throughout Europe. These dramas could be satirical or even irreverent, as in the case of the comic Mankind. This late fifteenth-century tale told the story of a “sinner” using obscene JOKES, jabs at church doctrine, and interaction with audience members. Unlike morality plays, the point of these performances was to entertain rather than educate.

Medieval dramas also began the evolution of theater that resulted in the rise of such literary geniuses as William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe (author of a FAUST play), and a host of European dramatists.

MEFISTOFELE Arrigo Boito brought the FAUST legend to Milan’s operator stage in 1868 with his flamboyant Mefistofele. Set in medieval times, the opera opens as the DEMON Mefistofele (MEPHISTOPHELES) brags that he can tempt any man away from God and that finding souls to add to the legions of hell is ridiculously simple. No sooner has he made this boast than the vain scholar Faust offers to surrender his soul to the netherworld in exchange for “enlightenment” about the mysteries of the universe. The DEVIL agrees and promises to show Faust the hidden truths of humanity.

The two embark on a journey toward the “Valley of Schirk” down a lonely road to the abode of SATAN. They arrive at the infernal fortress, a place of flames, tortures, and a thousand screaming voices, on Walpurgis Night, the witches’ sabbath. Faust watches the dance of the wizards with an exhilarating mix of excitement and terror. A coven of warlocks invites Faust to stir the black caldron and join in the revelry.

Through the next three acts, Mefistofele shows Faust “the Real and the Ideal,” satisfying his thirst for “human wisdom and knowing.” In the process, Faust seduces and then betrays “love” in the form of a human woman and of a goddess. Eventually, he sees the sorrow of humankind and laments his role in perpetuating that sadness. At last, the “death trumpet” sounds, and it is time to deliver his soul to damnation. But Faust repents at last and begs for mercy. A fierce battle breaks out between the forces of good and evil, the prize being his soul. Good ultimately prevails, and as Faust is received into heaven, Mefistofele sinks into murky hell, vowing to renew his diabolical efforts to corrupt all humanity.

MEMNOCH THE DEVIL Novelist Anne Rice, famed author of macabre books about VAMPIRES, takes on the ultimate supernatural plotlines in her 1995 best-seller, Memnoch the Devil. This fifth and last in the Vampire Lestat series sends the undead cad through space and time and ultimately to heaven and hell. Highlights of Lestat’s epic trek include witnessing the Crucifixion, losing an eye in a brutal underworld accident, and enthusiastically drinking menstrual blood. Between these escapades, Rice devotes the majority of her text to convoluted (and sometimes incoherent) theories about the nature of God, the evils of organized religion, and the “ever unfolding” process of evolution.

Approached by SATAN as he stalks his latest victim, Lestat is told “I need you” to assist in the battle for humanity. Satan, who now refers to himself as Memnoch, then takes Lestat on a tour of history, stopping to watch the fall of the rebel angels, the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden, and other historic events before taking him to the land of the dead. Afterward, he demands that Lestat make a choice: Will he serve God or the DEVIL?

The underworld of Rice’s imagination is the grim, dusty, somber SHEOL of ancient Hebrew tradition. In Sheol, departed spirits endure a bleak and unrewarding existence in an “awful, gloom-filled place” but suffer no physical pain. Their only sorrow is loss of their sensual earthly life and separation from God. In Memnoch, the souls in Sheol are further tormented by the belief that their Creator has abandoned them and forgotten his precious children. They struggle to “forgive” God for his cold indifference, but their hearts ache with a bitter, forlorn sadness.

Memnoch, a stylized version of traditional Satan, is depicted as an angel who has sinned by refusing to accept God’s new creation—the material world. In an attempt to understand its mysteries, he takes on flesh and visits the earth. Memnoch immediately succumbs to the sensual delights of his human body and begins indulging in sexual intercourse with the “Daughters of Men.” God demands that Memnoch return to heaven and account for these offenses against the “Divine Plan.”

But instead of apologizing and asking forgiveness, Memnoch rebukes God for abandoning humans to “corrupted ideas … and instinctive fear.” Angered that Memnoch places allegiance to humans over obedience to the Almighty, God sentences him to become “the Beast of God” on earth. He is damned to rule in hell and to be hideous to the human beings he so dearly loves.

According to Rice’s theological vision, Memnoch gladly accepts this new role, determined to use his powers to save souls rather than destroy them. He declares, “I will bring more souls through Sheol to Heaven than you will bring by your direct Gate.” Thus the underworld becomes a sort of PURGATORIAL HELL where human spirits cleanse themselves of unworthiness before ascending to heaven. Memnoch transforms the murky land of SHADES into a battlefield of frightening images and grisly phantoms, where souls must learn to forgive themselves for the atrocities they once committed. After matriculating in this infernal “school,” the damned graduate to paradise.

Rice’s novel stirred considerable controversy at the time of its publication for what many considered to be blasphemous treatments of God, Jesus Christ, and many important events in Christian history. According to the book, it is Memnoch, not Christ, who is responsible for the HARROWING OF HELL and for the release of souls languishing in Sheol. Sending Jesus to earth as the divine incarnation is likewise done at Memnoch’s prompting, since the DEMON suggests that this will help the Creator become more empathetic with humanity. Memnoch consistently portrays this fallen angel as a sympathetic, compassionate being while God comes across as an egotistical tyrant with no regard for the welfare of humankind. Rice’s depiction of hell has also been rejected by various religious scholars as ridiculous, illogical, and theologically absurd.

MEMORIALS Images of the underworld have been found on memorials throughout the globe. These include sarcophagi, tombs, mosaics, and other tributes to the revered dead. The earliest examples date back centuries before Christ, when Egyptians, Greeks, and ETRUSCANS alike burned with incessant curiosity about the afterlife. An ocean away, ancient Peruvian Indians were likewise embroidering images of CHTHONIC GHOULS tormenting human souls on death shrouds and burial wraps.

Relics of ancient Greece, such as intricate vases, murals, and carvings on tombs, often depict HADES and PERSEPHONE, the king and queen of the underworld. Families of the departed would place such images near the dead to try to win favor with the deities. Many believed that by honoring Hades and Persephone in this way, their loved ones would elude the horrors of the underworld and enjoy a more restful afterlife. Such compositions might also include other icons of Greek chthonic myth, such as the ferryman CHARON, the river STYX, and the monstrous guard dog CERBERUS.

A tomb found in the ancient city of Thebes is similarly decorated with pictures of souls riding across the river of death to the underworld. Mingled with the pleasant symbols of paradise are horrific scenes of the damned suffering in unending agony. Similar illustrations adorn sarcophagi discovered in Bologna and Volterra. Etruscan mortuaries reflect that culture’s obsession with death and the afterlife. Early tombs showed great feasts and celebrations, but these portraits later gave way to frightening depictions of underworld torture.

Ancient Egyptians decorated tombs with elaborate pictures of the afterlife, usually focusing on rich rewards in the next realm. Figures of Anubis and OSIRIS have been identified on numerous necropolises (cities intended for use by the dead). Many show the supernatural beast AMMUT waiting to devour the hearts of souls judged unworthy of paradise.

The spread of Judaism and Christianity largely ended the practice of using infernal images as ornamentation on memorials. Rituals designed to soothe and appease dark lords of the underworld were largely condemned as pagan magic by both Hebrew and Christian authorities. Clerics instead began stressing the ability of humanity to attain salvation by accepting the word of God, living a virtuous life, and asking for divine forgiveness. With this positive approach in mind, Christians and Jews began marking their graves with images of hope. Among followers of Christ, crosses (the symbol of redemption), Bible verses, and angelic figures became popular, while Jews routinely display the Star of David and comforting words of the Hebrew prophets.

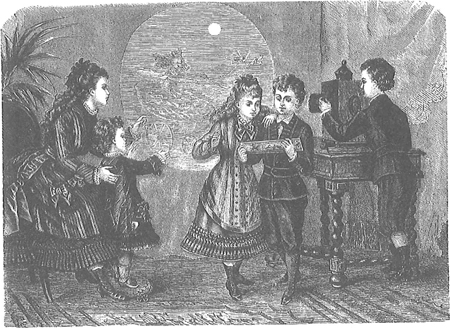

Detail of Charon Ferrying Souls on the River Styx, marble relief from a sarcophagus. ERICH LESSING/ART RESOURCE, NY

MEPHISTOPHELES Mephistopheles is one of the DEMONS of hell according to Christian literature and legend. He is mentioned in virtually every version of the FAUST story as the infernal agent who entices the scholar to sell his soul to the DEVIL. Mephistopheles is a shape-shifter who assumes many forms to tempt Faust and who can grant many supernatural powers. The fiend also takes Faust on a tour of hell to show the damned man what awaits him in the afterlife. In Christopher Marlowe’s version of the Faust tragedy, the demon goes even further, stating that he is the very embodiment of hell. When Faust asks how it is that the demon can leave the underworld, Mephistopheles responds, “Why, this is Hell, nor am I out of it.”

Mephistopheles has since become synonymous with the devil. Popular music icon Sting mentions the demon in his 1983 hit “Wrapped Around Your Finger,” likening the evil spirit to a beautiful—but forbidden—lover who can bring only sorrow and angst to her obsessed admirer. The host of hell has also inspired numerous plays, paintings, and works of music such as Arrigo Boito’s 1868 opera MEFISTOFELE.

MERLIN Merlin, the mystic wizard of Arthurian legend, is in some accounts the child of the DEVIL and part of a plot formed in hell. According to the story, the minions of hell conspire to aid an evil king, Vortigern, in conquering his enemies. They believe that his temporal victories will result in the damnation of many souls, thus increasing their infernal kingdom. But in order to win this diabolical assistance, Vortigern’s fortress must be fortified with the sacrifice of a fatherless child. So the DEMONS arrange to impregnate a virgin with SATAN’s seed.

The girl succumbs to the seduction and becomes pregnant. Regretting her sin, she seeks the advice of the wise cleric, Blaise, who vows to help thwart the devil’s plans. He hides the girl in a remote tower until she gives birth to a son. As soon as the child is born, Blaise baptizes him in the name of the Christian Trinity, calling the boy Merlin. Since he has been consecrated to Christ, he can no longer be used as a human sacrifice to the vile Satan. However, the boy has inherited tremendous mystic powers from his supernatural father. Much to the fury of the demons of hell, he uses these powers for good rather than evil.

Merlin is credited with many superhuman feats. Legend claims that at age five he successfully defended his mother in a notorious witch trial. He also had visions of otherworldly events that helped him give counsel to kings. The gifted sorcerer could shape-shift into many animal and human forms. Some accounts say that Merlin erected Stonehenge in a single night during the dark of the moon. His most famous role, however, is as adviser to the legendary King Arthur of the Round Table.

Legends also differ on how Merlin meets his demise. Some stories claim that he is tricked by the Lady of the Lake and damned to spend eternity in the trunk of an enchanted tree. Other versions state that he did not die, but lives on to this day in an underground library where he continues to study and philosophize. A particularly somber tale says that he accidentally sat in the Siege Perilous, the seat at the Round Table left empty to represent Judas and to warn against betrayal. When he sat down, a crack in the earth opened and Merlin was pulled down to the abyss. In any event, Merlin remains a perennial figure in the Arthurian legend cycle and tales of his extraordinary wisdom and powers persist.

MERRY HELL Though most interpretations of hell depict a horrid realm of misery, there is an opposite model of the underworld: a merry hell where those devoid of virtue experience an eternity of drinking, wantonness, and camaraderie. This glamorous inferno is presented as an attractive alternative to a “boring” heaven of stern do-gooders and sullen saints.

The play THE FROGS, written by Greek author Aristophanes in 405 B.C., first introduced the idea of a merry hell to the stage. In a parody of Greek tragedy, the underworld kingdom of HADES is portrayed as an ongoing party where singing amphibians, not fearsome monsters, stand guard. The Frogs was immensely popular with audiences who had grown weary of terrifying tales of a wretched afterlife awaiting them in the next realm.

This satirical treatment of the abyss evolved over the years, reaching its height in European MEDIEVAL DRAMA. Plays of this period featured fools costumed as DEMONS who ran out into the audience belching, shouting obscenities, and passing gas. They invited spectators to join them in the eternal “celebration” in the abyss. More elaborate productions included fireworks and small explosions to add glamour and excitement to the infernal foray.

MYSTERY PLAYS, dramas based on supernatural events of both pagan and Christian traditions, likewise depict the underworld as a magical place of merriment and feasting. The Devil Is an Ass, produced in 1616, shows SATAN as a comic buffoon attended by his minions, a colorful assortment of likable characters. And the early twentieth-century Off-Broadway production Hell, hosted by “Mr. and Mrs. DEVIL,” was declared a “profane burlesque,” raucous and rowdy in its irreverence. Similar depictions of a happy hell appear in AUCASSIN AND NICOLETTE and MAN AND SUPERMAN.

Today, the concept of a merry hell remains popular. Americans poke fun at the underworld through infernal JOKES, BUMPER STICKERS, CARTOONS, and T-SHIRTS. Performances involving a wickedly amusing inferno also abound. Modern examples of this hellish humor can be found on television programs LATE SHOW WITH DAVID LETTERMAN, SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE, and KIDS IN THE HALL.

MICHELANGELO Renaissance master Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564), artist, sculptor, poet, and architect, is considered by many to be the greatest artist in history. Born and raised in Florence, Michelangelo produced great works of CHURCH ART AND ARCHITECTURE in his beloved homeland and in Rome. His 1496 Pietà, which depicts a grief-stricken VIRGIN MARY cradling the lifeless body of her crucified son, won him worldwide acclaim and launched a career that continued for seven decades.

The prolific artist drew much of his inspiration from religion (he was a devout Roman Catholic) and concentrated on producing works depicting religious heroes. During his lifetime, he composed statues, paintings, and frescoes of biblical figures such as Moses, David, Adam, angels, and even the Almighty himself. But his creations also reflect the sorrows of his life: political unrest in Italy, recurring clashes of will between the temperamental genius and his often equally stubborn clients, and anxiety about the afterlife.

Michelangelo’s LAST JUDGMENT reflects his fascination with what awaits people on the other side of the grave. The massive work (considered the greatest interpretation of the subject ever painted) depicts stunned sinners disembarking from a somber boat ride into the land of the damned. Traditional IMAGERY of hell abounds: skeletons, snakes, and loathsome DEMONS. Jesus is depicted not as a gentle advocate but as a stern judge in the act of dispatching souls to unending torment. The mood of the painting is unsettling; the gallery of faces wrenched in agony conjures a sense of utter despair. So moving was his work that when Pope Paul III saw it for the first time, he fell to his knees and begged for divine mercy.

The artist includes some familiar faces among the damned. The likeness of papal master of ceremonies Biagio da Cesena, who upon seeing the Last Judgment before its completion denounced the work as “obscene,” can be seen in the face of MINOS, prince of hell. But Michelangelo does not limit his speculation about destiny to others; he has painted himself in the inferno as a flailed skin.

As Michelangelo aged, it was not beauty but faith that increasingly fueled his creativity. His later works depict subjects as “real” rather than “ideal,” recognizing the vulnerability of human souls. He continued to interpret religious themes while constantly speculating on his own ultimate fate. In his waning years, the artist referred to himself as having “a heart of flaming sulphur,” an ancient biblical symbol of hell.

Michelangelo died at age eighty-nine while working on a revised statue of Old Testament hero King David. This version shows the man’s human frailties rather than depicts him as the flawless ideal. The artist went to his death terrified of facing the infernal visions of his imagination yet hopeful that God’s infinite mercy would spare him from the terrors of hell.

MICTLAN The Aztecs, indigenous to central Mexico, believe the dead depart to Mictlan, a place of malaise rather than terror, but certainly no paradise. Mictlan is an arid desert where spirits shift aimlessly about in eternal tedium. They are not tortured but must endure this unending monotony. In addition to housing the dead, Mictlan contains the bones of an earlier race.

Mictlantecutli, the lord of the sojourn of the dead, rules the underworld with his wife, Mictlantecihuatl. He is depicted as an open-mouthed monster waiting to devour souls or as an owl clutching a skull and crossbones. The trickster god is associated with the color red. When the Christian missionaries began evangelizing Mexico, Mictlan was equated with SATAN, vicious tormentor of the dead.

This mythological underworld and its grim ruler are embellished in the SHORT STORY “The Road to Mictlantecutli,” written by Adobe James in 1965. In James’s adaptation, Mictlan is a horrific hell where evil souls face retribution for their sins.

MIDER Mider is the god of the underworld according to ancient Gaelic myth. He is a just overlord who does not torture spirits in his kingdom. His realm is a place of tedium and sorrow rather than physical pain. Mider has a magic caldron capable of performing supernatural feats. However, his daughter betrays him and helps the hero Cuchulain steal it from the underworld.

MILITARY INSIGNIA Throughout history, soldiers from around the world have incorporated infernal IMAGERY into their insignia. Examples of this date back centuries, to the first warriors who marched beneath flags emblazoned with such underworld images as DEMONS, DEVILS, flaming landscapes, tridents, pitchforks, and charred skeletal remains. The practice continues as modern elite troops both here and abroad proudly display logos featuring all manner of ghastly specters.

Contemporary examples of this abound: a French Special Forces patch depicts a green, horned devil toting menacing weaponry. Similar graphics adorn the uniforms of Italian Elite soldiers; these show a fierce SATAN wielding lightning bolts. American troops likewise borrow images from hell to strike terror into the hearts of their enemies. Popular infernal symbols include snakes, lizards, winged demons, flaming skulls, and vicious beasts analogous to the evil LEVIATHAN. The Grim Reaper (a derivative of Briton lord of hell ANKOU) makes an appearance on a U.S. Marines patch, straddling the word Deathwatch. Others simply include the word hell in their designs, conjuring fearsome images of the fiery underworld.

Easily the most recognizable use of afterlife imagery in military insignia is the SWASTIKA, used by the Nazis in the early part of the century. The origin of the swastika remains unknown, but representations of the symbol have been found on ancient relics of many civilizations. It is a sacred symbol in religions that teach reincarnation, used to illustrate the possible fates of the human soul. Each of the four branches depicts a specific judgment: to be reborn as a human, to be confined to the body of an animal, to be elevated to union with the gods, or to be damned to hell.

U.S. Army’s 2nd Armor Division emblem

Adolf Hitler was fascinated with ancient religions and saw the swastika as an emblem of sacred power. Using the basic design, his designers developed the hakenkreuz (hooked cross) to identify Hitler’s faithful. It was adopted as the official Nazi insignia in 1935 and was added to all banners of the Third Reich. Deeply superstitious, the Führer sought to give his troops a supernatural edge over the enemy and believed that forces marching under the mystic symbol would be unstoppable.

MINOS Minos is a judge of the dead according to both Greek and Roman legend. The underworld lord is derived from tales of a vicious king infamous for his tyranny. King Minos forced captured warriors and other prisoners to fight bulls in his labyrinth, a maze on the isle of Crete, for his amusement. They were not expected to survive the ordeal but to provide a good show for the king as their bodies were torn to bloody ribbons by the beasts. According to the tales, the vile king is eventually killed by one of his prisoners and thus became an overlord in HADES.

Minos appears in a number of works of art and literature. He is named as one of the judges of the underworld in the ancient GORGIAS by Plato. In Dante’s DIVINE COMEDY: THE INFERNO, he sits at the entrance of hell and determines to which circle of the abyss damned souls will be sent. Minos is similarly represented in the ODYSSEY, Homer’s epic account of a supernatural journey, and in Virgil’s AENEID. Art scholars identify Minos in RODIN’s sculpture GATES OF HELL and in MICHELANGELO’s LAST JUDGMENT.

Stephen King’s 1994 novel ROSE MADDER alludes to the ancient Minos as a bloodthirsty bull at the center of a subterranean maze. The malicious beast displays a callous disregard for human feelings and a disturbing capacity for cruelty. In a climax reminiscent of Greek epic quests, King Minos is challenged by the story’s heroine in a grisly confrontation of brute force and blind faith.

MORALITY PLAYS In the 1300s, church officials decided that MYSTERY PLAYS, dramas centering on Christian teachings about heaven, hell, and redemption, were becoming too secular. Religious leaders felt that the plays titillated rather than terrified audiences with lavish hell scenes, many of which depicted a MERRY HELL of eternal wantonness and carousing. Churches banned the offending productions and began offering morality plays. These productions adhered strictly to biblical text and official Christian doctrines. They often focused on the common person’s fight against evil in everyday life (represented by the DEVIL incarnate).

Common themes for these dramas included the war in heaven, creation of the earth, the HARROWING OF HELL, the prophesied apocalypse, the LAST JUDGMENT, and sufferings of the damned. Abstractions such as Lust, Honor, Obedience, and Gluttony were often personified and became the heroes and villains of these cautionary tales. Theatrical sets included elaborate HELLMOUTHS featuring dazzling emissions of smoke, fumes, and shrieks designed graphically to depict the horrors of the damned.

The 1654 production LUCIFER contains extensive scenes set in the underworld. DEMONS, gleeful when they learn that Adam has sinned, conspire to cause the damnation of generations of humanity. As the play proceeds, the condemned begin filling hell, wailing and cursing their fate. But when Christ arrives to harrow hell, he binds Lucifer’s hands and feet and takes the souls of the faithful with him to heaven. The savior then locks the doors of hell forever, leaving the demons in amplified agony. Such productions often used fireworks, explosions, and primitive pyrotechnic effects to create the great inferno.

The most famous morality play ever written is EVERYMAN, first performed around the year 1500. This English drama depicts the soul’s journey to the afterlife. When a typical sinner is called before the throne of God to face possible damnation, he must enlist the aid of a variety of virtues, renounce many vices and learn true contrition.

Morality plays began losing their appeal around the seventeenth century, when drama became the province of professional writers and performers. Today, revivals of such productions as Lucifer and Everyman are lauded for their historic importance and artistic merit rather than their religious educational value.

MOT Mot is the ancient Canaanite god of death and the archenemy of the benevolent god Baal. The legend of their battle, which dates back more than four thousand years, describes how Baal banishes Mot from the earth and confines him to the underworld. Unwilling to admit defeat, Mot dares Baal to visit him to the dark, foul-smelling land of the dead. Baal accepts this challenge, with disastrous results.

When Baal arrives, Mot forces him to eat mud, the “food of the dead.” This proves fatal, and Mot gloats that now Baal is in his kingdom and things are going to change. But Baal’s wife, Anat, refuses to surrender her husband so easily. She lures Mot out of his murky realm, then murders him and grinds up his body. A truce is eventually struck, and Baal returns to the heavens while Mot is restored to the underworld, where he must confine his exploits to torturing the damned.

MOVIE MERCHANDISING Infernal movie merchandising began as early as the 1960s with Aurora Plastics’ “monster kits” costing about $1 each. These glow-in-the-dark models promised “supernatural realism” of such screen fiends as the Wolfman, the VAMPIRE Count Dracula, and the Frankenstein Monster. The eerie kits were an instant hit, especially among adolescent boys. (Comparable models by Monogram Luminator currently sell for around $15.) Homage was paid to these terrifying toys in Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot, a film about vampires overrunning a New England village.

From such humble beginnings, underworld movie merchandising has boomed into a multimillion-dollar industry. Over the past few decades, retailers have jammed store shelves with NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET board games, BILL & TED’S BOGUS JOURNEY Grim Reaper dolls, and HELLRAISER Halloween masks. CHTHONIC movie villains can be found on watches, posters, makeup kits, COMIC BOOKS, action figures, stickers, and TRADING CARDS. Even “family-oriented entertainment” giant Disney Studios is getting into the act, peddling a vast array of trinkets depicting Greek lord of the dead HADES from its ANIMATED CARTOON adaptation of the HERCULES legend. These include water globes with revolving “scenes from the underworld” and a limited-edition wristwatch that “flames” at the press of a button.

Savvy promoters have taken hellish marketing a step further through tie-ins with other consumer outlets. Fast-food chain Burger King offered free BEETLE-JUICE and Ghostbusters toys with its children’s meals. Video renters were given the opportunity to collect actual scripts, press kits, and other memorabilia from Full Moon Entertainment’s supernatural thrillers DARK ANGEL: THE ASCENT, Lurking Fear, and Castle Freak. Cereal manufacturers began distributing Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey cassette tape holders and Addams Family flashlights with every “specially marked box” sold.

An assortment of promotional items from films on the supernatural.

Not surprisingly, the success of memorabilia adorned with movie scenes of hell has now spawned a cottage industry of secondary trade. Publications like the defunct TWILIGHT ZONE MAGAZINE and the current Sci-Fi are filled with advertisements offering promotional items from infernal films released years ago. A quick scan reveals enticements to purchase Nightmare Before Christmas stuffed dolls, Outer Limits collector cards, and Freddy Kruger “razor gloves.” There is also a heavy exchange of “vintage” marketing memorabilia at trade shows and flea markets around the country. With interest—and profits—in such memorabilia running high, the trend in mass-marketing of CHTHONIC movie merchandise promises to continue with no end in sight. As long as big-budget films about hell continue to be popular, the deluge of promotional items will likewise flow.

MUHAMMAD Muhammad (570–632), the prophet of Islam, claimed to have visited heaven and hell as part of a holy pilgrimage that led him to the “truths of Islam.” This supernatural journey is recorded in a first-person account similar to Dante’s DIVINE COMEDY: THE INFERNO. In the narrative, Muhammad vividly describes the terrain and inhabitants of JAHANNAM (hell) and offers warnings on how to avoid damnation.

The prophet Muhammad, founder of Islam. ART TODAY

According to his account, the angel Jibril (Gabriel) appears to Muhammad in 610 and reveals to him divine truth, which Muhammad transcribes. This text, known as the KORAN, is the holy book of Islam, their equivalent of the Christian Bible. Muhammad calls this writ the “word of Allah” (God). The Koran teaches that the soul is “prone to evil,” but Allah is a loving and merciful deity who gives humankind the tools necessary to attain salvation.

IBLIS (SATAN), the archfiend who opposes Allah, furiously toils to steer souls away from the truth and cause them to spend eternity in unrelenting agony. He manifests himself to Muhammad in many forms: a dog, a goat, a black DEMON riding a dark stallion, and a blaspheming Allah. As part of the revelation the prophet tours Iblis’s kingdom of hell, a place so thick with DEVILS that he cannot drop a pin without hitting one.

Muhammad also warns of the impending Last Day (sometimes called Day of Decision), a LAST JUDGMENT that will occur at the end of time. On the Last Day—a date known only to Allah—the soul of every person who has ever lived will be called before the Divine Throne to account for its life. Worthy souls will be allowed to enter paradise, but the spirits of the wicked will be damned to Jahannam, where they will eventually face ANNIHILATION.

Muhammad is held in great esteem by followers of Islam throughout the world. In 1988, Salman Rushdie angered millions of devout Muslims with his novel THE SATANIC VERSES, which describes a shallow and self-serving false prophet who is obviously patterned after Muhammad. The book was denounced in many countries, banned in others, and even resulted in a “death sentence” being placed on the author by some Muslim extremists.

MU-MONTO Mu-monto is a figure of Siberian mythology who visits the underworld and witnesses the rewards and punishments of the afterlife. Hoping to retrieve a stallion sacrificed to the memory of his father, Mu-monto travels to the far north seeking the entrance to the place of the dead. After overcoming many obstacles, he comes upon an enchanted boulder that separates the underworld from the land of the living. When he lifts the massive rock, a black fox crawls out and offers to escort him to the underworld.

Mu-monto accompanies the fox to the afterlife and learns that in death, justice is meted out according to the type of life each person has lived. There is no barrier between souls receiving reward and those being punished; it is the manner in which a person spends eternity that determines whether he or she is in paradise or hell. Unfaithful wives are stripped naked and lashed to sharp briars, and gossips have their mouths sewn shut. But those who were poor in life enjoy great banquets and fine wines; the sick and weak are healthy and vibrant. Mu-monto returns to his village with a warning to all that their actions in this life will indeed have dire consequences in the next.

MUSIC VIDEOS Ever since Elvis Presley scandalized millions with his onstage pelvic thrusts, rock and roll has been dubbed “the music of rebellion.” In this art form-turned-industry, artists frequently express the restlessness of youth by challenging the older generation’s traditions, and religion and morality are favorite targets. The more the Establishment protests, the more outrageous the spectacles become.

Rapid advances in technology brought performances into every American household via television. By the 1960s, top-selling artists were seen regularly on a variety of national programs. These televised performances evolved into short cinematic productions—music videos—and quickly became as popular as the songs themselves. Music videos proliferated, and by the early 1980s they were as essential to the success of a musical release as the audio recording. Shrewd marketing agents discovered that atrocious images yield massive publicity—and correspondingly elevated sales—and soon artists were gleefully including hell, SATAN, DEMONS, and orgies of the damned in their music video clips.

Hell has both visual appeal and psychological attraction for many performers. It is a sensual, exhilarating realm populated with those who brazenly indulge their wanton, carnal desires, celebrating rather than condemning the sex, drugs, and rock and roll lifestyle. And perhaps even more significant, the inferno is despised and decried by the older generation as a forbidden zone to be shunned and avoided. Directors blend these concepts into a MERRY HELL inhabited by scantily clad, voluptuous beauties, tanned musclemen, and grinning fiends engaged in a perpetual party. The intended viewers—teens and young adults—can assert their independence, assail their parents’ values, and flout societal mores simply by tuning in and singing along.

Of course, some infernal music videos are more playful than derisive. Bananarama’s 1986 clip for “Venus” features a leggy brunette sporting a skin-tight red leather DEVIL outfit complete with horns and tail. As she dances through a rocky terrain licked with flames, charred hands grab at her from a steamy pit. While this teasing ritual plays out, the song’s lyrics repeatedly probe “what’s your desire?”

Other artists incorporate more frightening visuals of the underworld into their videos. 1980s superstar Billy Idol routinely romped with an array of accursed creatures while crooning his macabre melodies. His “White Wedding” hosts a chapelful of undead guests scowling and howling at the bride and groom. In “Dancing with Myself,” Idol goes Hollywood, featuring among the “animated corpses” a hellion originally designed for and used in the horror film POLTERGEIST.

COUNTRY MUSIC, too, has prowled the depths of hell for interesting video footage. 4 Runner’s hit “Cain’s Blood” and Mark O’Connor’s “The Devil Goes Back to Georgia” offer flashy images of CHRISTIAN HELL. Both songs weave passages from the Bible into the lyrics and offer cautionary tales about damnation. The accompanying visuals suggest a hell of leaping flames, smoldering landscapes, and flowing lava. And unlike its rock and roll counterparts, country music’s inferno is a place of punishment and terror rather than an eternal festival of the flesh.

Even “neo-classical” music is getting into the infernal act. A visual adaptation of Andrew Lloyd Weber’s title song from Phantom of the Opera contains symbols from ancient CHTHONIC myths. The promotional video shows a boat navigating the river STYX, silent ferryman CHARON, and the kingdom of HADES from the underworld of Greek legend.

The undisputed master of hell in modern music is HEAVY METAL MUSIC, and nowhere is that more evident than in music video clips. From the first airings of NBC’s Friday Night Videos (a precursor to Music Television [MTV]) and other similar programs, a host of self-proclaimed Satanists and death-obsessed performers belted out their ballads before a burning, beastly backdrop. Fans of the genre, typically dressed all in black and sporting demonic TATTOOS, were mesmerized by the unorthodox visuals. Underworld scenery had found its viewing audience.

Dio’s video for the 1984 hit “The Last in Line” blends images of courage, mythic quests, and divine retribution. The clip shows an odious fiend overseeing an assembly line of damned humans slaving in a steamy orange pit. Leather-clad lead singer Ronny James Dio moans, “We are after the witch, we may never, never, never return,” as he wades through the murky mess in an attempt to free the lost souls. Dio’s brash style and unflinching valor recall centuries-old MORALITY PLAYS, in which heroes face demons and imperil their lives in the name of honor.

By the dawn of the 1990s, hell had become equated in many artists’ viewpoint with the specter of nuclear annihilation. This is reflected in several of British band Iron Maiden’s videos in which warmongers are the demons who threaten humanity. In “Can I Play with Madness?” a schoolboy grows bored with the incessant droning of his uninspired teacher. He flees the classroom and discovers a passageway to the underworld. Crawling through, he finds a realm of violence, pain, and senseless destruction. The enraged professor follows the child, representing the inescapable reach of authority, both civic and divine.

One of the most popular Heavy Metal groups of the decade, Guns ’n’ Roses, blurs the line between the agony of life and the horrors of damnation. The 1991 video for “Don’t Cry” shows lead singer Axl Rose trapped in a dark grave. Another scene includes the ghost image of a newspaper bearing the headline “Hell Revisited.” The shivering, naked Rose ultimately visits a gloomy morgue, where his dead body is being examined. His hell is the icy cold of isolation and alienation rather than a chaotic, blazing inferno.

At the height of their popularity, these and other Heavy Metal videos were showcased on MTV in a regular program called Headbangers’ Ball. (The term refers to the typical “dance” associated with Metal music, in which listeners violently rock their heads back and forth along with the beat.) The show was hosted by “Metal enthusiast” Riki Rachtman, who had been a devotee of the genre long before Music Television hit the airwaves. Each hour-long episode was packed with images of the abyss, grotesque demons, and hellish artwork. Headbangers’ Ball was canceled when “alternative” music began gaining in popularity, greatly diminishing the prominence of Heavy Metal and its filmed performances.

Today, hell still surfaces occasionally in a variety of videos for rap, urban contemporary, and “grunge” songs. The music of Generation X, and its visuals, are considered pessimistic and cynical, often depicting the world as a joyless realm that must be endured rather than celebrated. With this prevailing attitude, the prospect of damnation is a hollow threat that generates more snickers than shudders. Hell has lost its capacity to shock and horrify, perhaps from overexposure during the past decades.

MYSTERY PLAYS Mystery plays describe a diverse genre of drama. Productions range from ancient images handed down from the Egyptians to Christian performances about the nature of the afterlife. Pagan dramas usually focus on rituals and magic spells as preparation for death and avoidance of punishment in the afterlife. The most common of these were plays dedicated to OSIRIS, the ancient Egyptian lord of the netherworld. During the productions, men stood in pits representing the land of the dead while animals were offered as sacrifice. The blood of the beast was then used to bathe the body, purifying the spirit and protecting it from the terrors of the underworld.

Most Christian mystery plays developed as an outgrowth of HELLFIRE SERMONS. Originally written in Latin (the language of the Christian church), these dramas were designed to educate the peasantry about biblical events and persuade, perhaps even frighten, followers into obedience. Eventually, these dramas were performed in the audiences’ native languages to increase their appeal to the masses. The vast majority were based on passages from the Bible and were presented by local churches, usually to commemorate some important event or feast day. Such topics as heaven and hell, the LAST JUDGMENT, and the HARROWING OF HELL were especially popular.

Hell was always a favorite setting among performers and audiences alike. The most sophisticated troupes had props that belched smoke and shot flames from trapdoors below the stage flooring to graphically represent the dark abyss. Many included mechanical monsters and explosions of sulfurous fumes. Townships began competing for bragging rights as to which had the most exciting hell scene, adding splashy color, imaginative creatures, and special effects to the play. (Such grisly and terrifying productions were the forerunner of today’s monster movies and horror films.)

Drawing of a Baroque set for mystery plays c. 1550, with elaborate hellmouth at stage right. ART TODAY

This emphasis on style over substance led to a change in the nature of hell in these mystery plays. Rather than a pit of pain and despair, the underworld slowly evolved as a place of magic, enchantment, and revelry. This popularized the concept of a MERRY HELL where the bold and glamorous partook of forbidden delights, often incorporating exotic ideas from ancient myths and legends. No longer defined by Christian tradition, hell became a home for FAIRIES, pagan heroes, and ruthless champions.

Due to this glamorization of hell and shift away from traditional Christian doctrines, mystery plays were criticized and eventually condemned by thirteenth-century church officials who declared them evil, vile, and dangerous to the soul. As the plays became less and less theological, they were supplanted by MORALITY PLAYS, tales designed to teach lessons about ethics and behavior. These dramas continued to be the province of the church and were strictly overseen by religious authorities.