RADISH Radish is a hero of ancient Buddhist legend who travels to AVICI, the lowest circle of hell, to free the soul of his condemned mother. According to the tale, Radish learns of her damnation and vows to reclaim her spirit from this place of infernal torture. He journeys to the land of the dead with the help of incantations and magic spells but is unable to recognize his mother as she has been transformed into a dog. This is punishment for refusing food to a temple priest. When Radish realizes that his mother is now reduced to the shape of an animal, he begs the gods for mercy on her behalf.

His pleas touch the hearts of the deities, and they agree to allow her to return to the living world on one condition: She must dedicate her life to works of charity. Radish likewise must promise to strive for justice and compassion in order to end the curse. Both pledge themselves to this quest, and the two return to the upper world to fulfill their mission.

RAIKO Raiko is a legendary Japanese nobleman revered for his virtue and generosity. He is asked by the people of Kyoto to help rid the village of its DEMONS. Raiko agrees and is immediately stricken with fever and begins experiencing frightening visions of hell. The Kyoto demons, unwilling to be purged, taunt Raiko that they will one day have both his body and his soul.

The apparitions of the underworld grow increasingly horrific, and Raiko finds them so realistic that he starts believing that they are not hallucinations but actual experiences. In the most terrifying, Raiko is suspended on a huge web as a gigantic spider (representing evil) slowly moves toward him. As the spider draws closer, Raiko manages to seize his sword and cut himself free of the web. He then thrusts the blade into the creature, leaving it alive but severely wounded. The battle ended, Raiko collapses into a deep sleep that lasts for days.

Upon awakening, Raiko finds that his fever has lifted—and the demons that have been terrorizing Kyoto have mysteriously disappeared.

RAPTURE, THE Evangelical Christianity, the millennium, and concepts of CHRISTIAN HELL and salvation are probed in The Rapture, a 1991 supernatural drama. The film stars Mimi Rogers as a restless, world-weary woman who tries to escape the tedium of her life through wanton sexual escapades. This, too, soon becomes unsatisfying, and she moves on to a new obsession: charismatic Christianity. Rogers joins a congregation that believes the end of the world and the LAST JUDGMENT are imminent and that total surrender to God is necessary to avoid eternity in hell.

Rogers’s character grows even more zealous when her husband is murdered in a senseless act of violence. Still in shock over his loss, she becomes convinced that God wants her to take her young daughter (played by Kimberly Cullum) with her to the desert to be assumed into heaven. She leaves her home and possessions behind and arrives penniless in the desert. But when the days pass and God has not delivered them, Rogers grows impatient and shoots her little girl, believing that the child will be better off in paradise. Fear of hell stops her from committing suicide, since she believes “you can’t go to heaven if you kill yourself.” Her faith turns to rage as she mourns her dead child.

While in the desert, Rogers meets a sheriff (played by Will Patton) who embodies the true spirit of Christ: He feeds the hungry, shelters the homeless, visits the imprisoned. He has no “religion” but displays a thirst for understanding and hope. The two engage in several discussions about philosophy and belief, but Rogers must ultimately admit, “I’m afraid of hell,” and that is the basis for her religious adherence. When asked if she loves God, she must respond, “Not anymore. He has too many rules.”

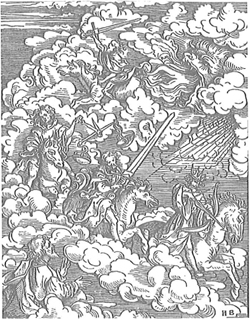

The night following Cullum’s death, the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse described in REVELATION arrive to signal the earth’s destruction. Cullum appears to Rogers in her jail cell and quotes from the scripture of the “last days,” declaring that the Last Judgment is about to take place. The girl urges Rogers to seek God’s forgiveness, but her mother stubbornly insists that God must first explain himself and justify why there is “so much pain and suffering in the world” that he created. “Let me ask him why,” she demands, then perhaps she will repent.

For Patton, no explanation is necessary. His faith is simple and sincere. The film ends as he and Rogers stand on the brink of eternity, in a vast wasteland of darkness. “Is this Hell?” Patton asks as the two stand alone in the void. Cullum approaches and replies that they are on the banks of “the river that washes away all your sins.” Heaven, she points out, is off in the distance. Patton, who is honestly able to profess his love for God, departs to paradise, but Rogers, bitter and resolute, refuses to go. She stands in the seamless gloom of hell, a chasm of nothingness, while her daughter’s spirit joins the saved in heaven. Rogers must endure this cold damnation, without light, without love, without hope, “forever.”

The Rapture makes a bold statement about devotion in the juxtaposition of Rogers and Patton. The former is an avowed “true believer” who attends services regularly and can quote Holy Scripture verbatim. Patton, on the other hand, is a kind-hearted gentleman who has had absolutely no formal religious training. Together, they represent the spectrum of human spiritual experience. The film likewise puts forth an interpretation of hell by defining its opposite. Damnation, in this view, is isolation from God, from loved ones, from beauty, and ultimately from love itself. The Rapture differentiates itself from other infernal films by asserting that the everlasting abyss is not reserved for murders, rapists, and pagans, but can be “chosen” by the pious as well.

RATI–MBATI–NDUA Ratimbati-ndua has been called the SATAN of Fiji. He is a ravenous beast whose name means “one-toothed DEMON,” and he delights in devouring the dead. When Rati-mbati-ndua flies through the night sky seeking victims, he leaves a burning meteor trail in his wake.

RAWLINGS, MAURICE Renowned cardiologist Maurice Rawlings, M.D., explores negative NEAR-DEATH EXPERIENCES in his 1993 book To Hell and Back. Rawlings had often heard of such mystic voyages in the course of his work, but he routinely dismissed them as hallucinations. He believed that “patients who reported an after-death experience were a little crazy.” A self-described cynic, Rawlings focused on the physical consequences of life-threatening episodes and left the spiritual implications to the clergy.

That attitude changed dramatically in 1977 while he was administering cardiopulmonary resuscitation to a man whose heart had stopped. As Rawlings worked, he was surprised when the frantic patient screamed, “For God’s sake, don’t stop! Every time you let go, I’m back in Hell!” Rawlings was accustomed to having recently revived patients yell at him to stop, declaring “you’re breaking my ribs!” but he had never before been asked to continue. The man then asked Rawlings to pray with him, a request that left the cardiologist feeling “insulted.” But he deferred to his patient’s request, mumbling what he termed a “make-believe” prayer.

After the patient was revived, he told Rawlings a ghastly tale of being tortured among the damned. The doctor had heard many accounts of positive near-death and out-of-body experiences, but this was his first encounter with a negative one. Intrigued by the novelty of this story, Rawlings began interviewing emergency room personnel from across the country to see if similar incidents were occurring elsewhere. He kept of file of these reports, dubbing them “Hell cases.”

Over the next decade and a half, Rawlings spoke with hundreds of patients who had been clinically dead and the doctors, nurses, and medical technicians who attended them. He compiled these accounts in To Hell and Back, the first book to focus on such repugnant near-death experiences. The work describes the specifics of trips to the underworld and explores the reasons why only happy, peaceful stories receive mass-media coverage.

The descriptions of the underworld recounted in To Hell in Back vary, but they are all distinctly unpleasant. One patient initially sees the proverbial “tunnel of light” but is horrified when it catches fire as he walks through it. The fiery passage burns “like an oil spill.” Another account tells of a “conveyor belt” that spews huge, oddly colored puzzle pieces at the damned. The pieces “had to be fitted together rapidly under severe penalty from an unseen force.” There is no heat or physical torture, but the pressure of working on this deranged assembly line is unbearable.

Equally terrifying is another woman’s story of finding herself in a barren wasteland teeming with naked “zombie-like people standing elbow to elbow doing nothing but staring” at her. It is like being abandoned in the ward of an endless insane asylum. Many patients had their horrific experiences compounded by recognizing friends and family members among the tenants of hell.

To Hell and Back also poses some innovative theories about the connection between visions of hell and UFO abductions, which the author theorizes originate from the same diabolical source.

REPUBLIC Fourth-century B.C. Greek philosopher PLATO wrote many dialogues that speculated on the underworld, including the Republic. This treatise examines the concept of justice by describing a utopian society where everyone is treated fairly, the good are rewarded for their virtue, and evildoers receive just punishment. In contrast, he likens this world, the human plane, to a cave where humans are chained prisoners trying to interpret the shadows that surround them.

Plato describes in his Republic an elderly man who rebukes the youthful for dismissing the notion of a grim hell as nonsense. When a person is young, he tells them, he thinks himself immortal. The very thought of death, much less an afterlife, is inconceivable. But as years pass, the reality of the grave becomes undeniable and the possibility of damnation becomes increasingly frightening. The old man warns his young friends that they, too, will one day spend many restless hours pondering the world to come and fearing the torments that might await in that realm.

The Republic also features a passage regarding TARTARUS, the darkest pit of HADES reserved for the worst sinners. In the dialogue, Socrates tells the “Myth of Er,” about a famous soldier who “dies,” visits the underworld, then returns to tell his fellowmen about final justice. When Er falls on the battlefield, he is believed dead, and his SHADE (soul) joins a legion of departed spirits on a journey to the afterlife. In the next world, Er sees two chasms in the sky and two cutting into the earth. Between the chasms are judges who direct the souls into the appropriate chamber. Virtuous spirits are sent to the sky’s upper right opening; damned souls are relegated to the earth’s left chasm. Out of the other two channels, a steady stream of spirits is continually exiting.

Unlike the bright, joyful shades emerging form the sky, spirits leaving the earth are dirty, weary, and haunted. They tell of fierce DEMONS “of fiery aspect” who torture the damned without pity in a gloomy chamber where sinners are punished “tenfold” for their crimes. These vile fiends then hurl condemned spirits into the deepest pits of Tartarus, where they find no relief from their agony. Some souls are so steeped in their own corruption that they will never be released.

Er then travels with the purged spirits to the altar of the Fates, where souls are returned to the earth. Each one can choose what sort of life he will have in the next incarnation and inherently accepts the rewards and risks that accompany the selection. The Greek musician ORPHEUS asks to return as a swan; Odysseus, hero of the epic ODYSSEY, has had his fill of adventure and requests a simple, quiet life. Before embarking on the next destiny, each shade drinks from the river LETHE to forget his former existence. But Er is forbidden to do so, since he must remember and share his tale.

Plato’s message in the Republic is that each person is responsible for his or her own actions and must be prepared to face the consequences. He reiterates this point by reminding readers that there is no escape from justice, since those who are evil in this life will be forced to pay for their sins in the next.

REVELATION The oldest depictions of CHRISTIAN HELL originate in Revelation. This book of the Bible was written by St. John the Evangelist while he was in exile for preaching Christianity and is based on visions he experienced during the first century A.D. In this extraordinary work, St. John describes a number of supernatural events, including the rebellion of LUCIFER, the creation of hell, and the impending LAST JUDGMENT. He offers this brief depiction of Lucifer’s betrayal: “… there was a war in Heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon [Lucifer]; and the dragon fought and his angels, and prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven” (Rev. 12:7–8).

The greater part of Revelation is devoted to foretelling the cataclysmic events that will mark the destruction of the world. St. John describes an Antichrist who will try to corrupt humanity, numerous natural disasters that will claim millions of lives, and a horrible beast similar to LEVIATHAN, the oceanic monster of the Old Testament. He warns that when these things come to pass, all humans will be called upon to account for their lives before being damned to hell or welcomed into paradise: “And the sea gave up the dead which were in it; and death and HADES delivered up the dead who were in them. And they were judged, each one according to his works” (Rev. 20:13).

Revelation contains frequent references to SATAN and to the “Lake of Fire” that awaits the iniquitous in the world to come. The author calls damnation a “second death” that ravages the soul in the manner that physical demise destroys the body. This ultimate suffering is the loss of God and the everlasting separation from the Almighty’s love, beauty, and joy.

RODIN, AUGUSTE French artist Auguste Rodin (1840–1917) has been called the best sculptor since MICHELANGELO by art scholars across the world. His 1877 sculpture The Bronze Age was so realistic that patrons believed that this was not a statue at all but a human being encased in metal. But Rodin’s greatest creation is the GATES OF HELL, an elaborate set of brass doors for the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris. Despite being left unfinished at the time of his death, the composition is a triumph in artistic accomplishment.

A 1498 illustration by Albrecht Dürer of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse from Revelations: War, Hunger, Plague and Death. ART TODAY

Gates of Hell is a massive sculpture illustrating the horrors of the underworld. Rodin uses images from Dante’s DIVINE COMEDY: THE INFERNO, Peter Paul Rubens’s THE FALL OF THE DAMNED, and Michelangelo’s LAST JUDGMENT in creating a visual spectacle of CHRISTIAN HELL. Its single most famous component, The Thinker, depicts a condemned soul contemplating his fate at the doorway to damnation.

Rodin’s work is significant in that it combines styles and symbols of classic art and literature into a contemporary depiction of the underworld. Gates of Hell is among the most complex and ornate compositions of the past centuries and serves as a testament of people’s lingering preoccupation with the realm of the damned even in the Age of Enlightenment.

ROSE MADDER Stephen King’s Rose Madder, a 1994 novel about a woman fleeing her abusive husband, includes allusions to HADES, the mythical underworld of ancient Greece. His tale of innocence, violation, and retribution includes images of the river LETHE, with waters that make mortals forget their lives, the ERINYES (Fates) who torment iniquitous souls, and the evil King MINOS, lord of hell featured in Dante’s DIVINE COMEDY: THE INFERNO as judge of the damned.

The novel tells the story of Rosie McClelon, a battered wife who wants only to be rid of her vicious husband, Norman. But when she tries to escape, Norman tracks her across the country with murder on his mind. Rosie’s only hope lies in a parallel world where a mysterious goddess offers ominous assistance, statues come alive, and wicked men are transformed into hideous beasts. It is a place of final reckoning, where justice is inescapable.

When Rosie and her boyfriend, Bill Steiner, enter the supernatural realm to battle the forces of evil, Bill asks, “Is this the afterlife?” But the response is deliberately vague, as King implies that rage itself is what truly damns us. This internal anger makes existence intolerable and threatens happiness in any plane.