SAINT PATRICK’S PURGATORY An Irish legend dating back to the mid-1100s includes a description of St. Patrick’s purgatory, a place of great suffering for those who die without repenting their sins. Sir Owen, an adventurous knight, explores the region as part of his extensive travels.

Escorted by demons, Sir Owen visits the PURGATORIAL HELL, a putrid cavern located on a desolate island near County Donegal. Within its borders, souls are boiled in sulfur, thrown off cliffs, gnawed upon by monsters, and forced to endure bitter cold and excruciating heat. The region is permeated by a horrible stench of decay and burning flesh. Sir Owen must exit St. Patrick’s purgatory by crossing a narrow bridge over a river of fire. Fearing for his safety, he kneels and begs for God’s mercy and is mystically transported over the passage by divine intervention. The terrified knight then flees the accursed realm, vowing to live a virtuous life lest he be sent back to this hell after his death.

SAMHAIN Samhain (meaning “summer’s end”) is the ancient Celtic lord of the dead. Legends dating back to the days of the Druids explain how the worlds of the living and the dead come together at the feast of Samhain, a break in time between the end of autumn and the start of winter. As the Celts measure days from sundown to sundown, Samhain begins at dusk on October 31, the last day of fall. During this night and until dawn on November 1, damned spirits, DEMONS, and FAIRIES rise from the underworld to scour the earth, desperate to satisfy their bloodlust.

The Celts believed that the land of the dead exists directly below the hills of the Irish countryside and that certain spells and incantations could raise the spirits of the deceased. They lit bonfires and set out food for the ambulatory damned, hoping to appease them. Peasants wore masks resembling demons and GHOULS to make themselves blend in with the risen dead. On Samhain, no one went out alone.

One story tells that during Samhain, a witch summons from hell the soul of the Shadowman, an ominous spirit believed to have great supernatural powers. When the abyss is opened, the Shadowman steps forward amid an explosion of fire and sulfurous smoke. The enraged spirit demands that he be returned to the underworld, but the witch is unable to reverse the spell. In some versions of this tale, the Shadowman is left to wander the earth prowling for souls to steal. In others, he is destroyed by Irish folk hero Finn MacCumal.

Today, Samhain has been tamed into Halloween, a children’s holiday celebrated with costumes, candy, and pranks. The modern custom of trick or treating originates from the ancient festival: Druids went door to door asking for wood to feed their sacrificial fires. If the residents refused to supply any, a curse was placed on the household. But those who gave scraps of timber were rewarded with protection from the marauding dead.

Carving pumpkins into Jack-o’-lanterns is likewise a remnant of Samhain. Many believed that souls of the dead could be confined in physical containers. Pumpkins, roughly the size of a human head, were hollowed out and decorated with faces to serve as receptacles for the raised spirits. The name derives from an Irish legend about a miser named Jack who plays practical jokes on the DEVIL. When he dies, neither heaven nor hell will accept his soul. He is condemned to wander the earth with his lantern until the LAST JUDGMENT, at which time God might show him mercy.

John Carpenter’s classic 1978 horror film Halloween contains reference to Samhain and its rituals, bringing the age-old evil into the twentieth century via a diabolical villain who seems unstoppable. Like his ancient precursor, the fiend has a thirst for human sacrifice.

SATAN Satan is lord of DEMONS and ruler of hell in Christian and Jewish tradition (called IBLIS in Islamic texts). His name is the Hebrew term for “adversary,” as Satan’s mission is to frustrate the will of God. He is referred to in the Bible as “the liar,” “angel of the bottomless pit,” and “the enemy.” Satan is sometimes identified as LUCIFER, the angel of light, although religious scholars insist that the two are separate beings. Confusion arises from passages in REVELATION: “There was a war in Heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon and the dragon fought and his angels and prevailed not; neither was their place found anymore in Heaven. And the great dragon was cast out, that old serpent, called the Devil, and Satan, which deceiveth the whole world” (Rev. 12:7–9).

The name Satan is never applied to the angel while still in heaven, only after the fall, although Lucifer is used interchangeably. He is also known as the Prince of Darkness, the Beast, the DEVIL, Black Angel, and Lord of the Abyss.

One thing is clear: Satan, although God’s adversary, is not his equal. The Bible states that Satan shall have power “in this age” but that he shall be vanquished in “the age to come.” The DEMON has already suffered a painful defeat by Jesus Christ called the HARROWING OF HELL. According to Christian doctrine, after Christ’s crucifixion, the redeemer raids the underworld and delivers the souls of the virtuous dead to heaven. A second victory over Satan is foretold at the LAST JUDGMENT, when the earth will be destroyed and the fiend will be bound for eternity in the pits of hell.

Satan is a key figure in hundreds of works of Western literature, most notably PARADISE LOST, FAUST, DIVINE COMEDY: THE INFERNO, and PIERS PLOWMAN (in which he is clearly identified as being distinct from Lucifer). The dark angel is also prevalent in MORALITY PLAYS, MEDIEVAL DRAMA, MYSTERY PLAYS, and artworks. In modern times, Satan is often a curiosity glamorized in HEAVY METAL MUSIC performances or satirized in sketches on SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE, KIDS IN THE HALL, films such as STAY TUNED and BILL & TED’S BOGUS JOURNEY, and in product ADVERTISING.

SATANIC VERSES, THE Author Salman Rushdie was catapulted to international fame in 1989 when Islamic leaders demanded that the writer be executed. The death sentence came in response to publication of Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, which irate Muslim clerics denounced as blasphemous and despicable. The book was banned throughout the Islamic world and even in India, Rushdie’s native country, where authorities worried it would inflame tensions between warring religious groups.

Objection to the work stemmed from the fact that the main character, Mahound (an ancient name of the DEVIL), closely resembles the historic figure MUHAMMAD, founder of Islam. Mahound is depicted as a fanatic who claims to be receiving messages from an angel but is actually creating a religion according to his own whims. The faith he preaches is constantly “spouting rules, rules, rules … rules about every damn thing” that focus on mind control rather than spiritual development. And, as is often the case with Muslim extremists, criticism is met with anger and condemnation. Mahound calls all dissent “devil’s talk” and encourages followers to surrender their free will and “trust the Book.”

The Satanic Verses opens with the explosion of a hijacked airline over the English Channel. Amid the debris, two passengers, a legendary Indian movie star named Gibreel Farishta and television voice-over specialist Saladin Chamcha, float gently to the earth, seemingly unharmed. But as they resume their lives, they begin to notice remarkable changes. Saladin’s legs mutate into cloven hoofs, sharp horns grow from his temples, and he realizes that “some demonic and irreversible mutation is taking place in my inmost depth.” Gibreel, too, finds that he has been changed. He now has a visible halo and radiates a “distinctly golden glow.”

The book then launches into an allegory of the eternal battle between good and evil and the corresponding duality of humanity. As the characters soon learn, it is often difficult to tell who is angel and who is DEMON in this confusing realm. “Ghosts, Nazis and saints” dwell together, and salvation and damnation seem to be almost interchangeable. Even the two men, despite their new shapes, are uncertain about their own personal morality and their role in the grand scheme of destiny.

The Satanic Verses further illustrates the ongoing war by interweaving tales of Mahound and his unholy faith into the story of Gibreel and Saladin. Mahound calls himself the Prophet of Jahilia (City of Sand), a desolate place that resembles JAHANNAM, Islamic hell. At one point in the text, the dark angel Beelzebub and his demon legions take notice of the self-proclaimed holy man and ask, “Is he with us or not?” Even Mahound’s scribe, who had given up everything to follow the prophet, begins to wonder if perhaps he has made a tragic mistake.

As Mahound’s religion degenerates into a massive tangle of bureaucratic regulations, he keeps followers in line by reminding them of the dire consequences of disobedience. Those who scoff at “divine law” or refuse to obey will surely be cast into the raging inferno. Mahound teaches that this abyss is a PURGATORIAL HELL, a harsh realm where souls are purified of sin through various tortures and torments. “Even the most evil of doers would eventually be cleansed by hellfire,” Mahound tells believers, albeit after much indescribable suffering.

Rushdie’s massive work is also a study in the cyclical nature of life. Characters experience life, death, sin, forgiveness, adventure, homecoming, division, and resolution. The author accomplishes this by mingling religious concepts with fragments of Arabian folktales and other myths, creating rich stories within stories. His lesson is that hell, like heaven, is a state of being that can exist anywhere, even in the most unexpected places.

SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE Over its twenty-plus-year run, the comedy series Saturday Night Live has found numerous ways to lampoon hell. Segments poking fun at the underworld have included ADVERTISING spoofs, jabs at SATAN, song parodies, and even a lambasting of tabloid newspapers sensationalizing the everlasting inferno. Hell also arises frequently as the punchline of the show’s infernal JOKES and ironic CLICHÉS.

In one 1983 sketch, a commercial for a tabloid offers to inform “inquiring minds” whether the recently deceased Gloria Swanson ascended to heaven or was damned to hell. The spot includes a look at the abyss, depicted as a flaming pit into which Swanson’s photo is dropped. During the same season, cast member John Lovitz’s SATAN was a recurring character, routinely popping up to antagonize guest stars and encourage DEVIL worship. His costume consists of a bright red satin suit with matching cape, black horns sprouting from his temples, a red tail, and a pitchfork. At the close of each such appearance, Lovitz would press his face against the camera and chant, “Worship me! I command you!” then erupt in maniacal laughter.

Another cast member, Christopher Guest, revived his role as guitarist for satirical HEAVY METAL group Spinal Tap for a demonic Christmas song. The holiday carol “Christmas with the Devil” describes what the yuletide season is like in hell. According to the lyrics, the “elves are dressed in leather,” the “sugar plums are rancid,” and the “stockings are in flames.” During the performance, elfish DEMONS frolic wickedly as black snow blankets the stage. In a mock interview with the band, Guest quips, “A man’s relationship with the devil is a very private thing.”

Beer advertisements receive a grand bashing in a commercial spoof about what overachievers “deserve.” Toasting one another with golden brew, the characters comment on how they have sold condominiums at five times their original value, climbed the corporate ladder at all costs, and shed the draining influences of family and friends. The tag line promises, “For all you do, you’re gonna PAY!” as the “beautiful people” suddenly find themselves cast into the fiery bowels of hell. The now-screaming yuppies are tortured by demons as the narrator coos that this, quite simply, is justice.

Traditional religious depictions of the underworld have also been fair game. A 1994 sketch features guest host Patrick Stewart as a less than impressive Satan trying to discipline a band of wisecracking demons. Stewart, perched on a crimson throne in a smoky, cavernous kingdom dotted by leaping flames, showers his throng with bad jokes and ridiculous curses. When they mock him for his inane comments, he turns the fiends into “burning monkeys.”

Comedian Jim Carey satirizes infernal clichés in the 1996 “See You In Hell” sketch. Carey plays an impetuous businessman who responds to virtually every comment with a hardy, “I’ll see you in hell!” He writes the phrase on checks, uses it to greet his friends, drops it into party conversation. The segment ends with reunion in the underworld where Carey and his comrades do meet again amid the flames, smoke, and stench of the great inferno.

SCENES FROM THE CLASS STRUGGLE IN BEVERLY HILLS In a dark parody of the shallow lifestyle of affluent 1980s Californians, Scenes from the Class Struggle in Beverly Hills features an amusing commentary on the nature of hell. Writer Bruce Wagner creates a scenario where servants and their wealthy employers live in the same locale but worlds apart, both in this life and the next.

The film follows the adventures of a self-absorbed widow (played by Jacqueline Bisset) who is routinely visited by the ghost of her equally vacuous, recently deceased husband (played by Paul Mazursky). Mazursky has accidentally killed himself in a mishap with autoeroticism and is now a resident of the smoky abyss. When asked why he keeps reappearing, the accursed man passionately exclaims about departed souls, “They live, they feel, they desire.” His loneliness has driven him out of hell and back to Bisset’s side.

Mazursky’s ultimate goal is to convince her to join him in hell where they can resume their existence together. Trying to persuade her, he describes the realm of the damned as a close parallel to Beverly Hills, even noting he has a house “just like this one” picked out for them in the inferno. Mazursky assures his wife, “You’ll love it in hell,” and in fact will hardly notice the difference between the two worlds.

But even in death, the peasants and the privileged inhabit different realms. While Mazursky sketches a great below of lavish homes, expensive cars, and manicured lawns, the Chicana maid Rosa (played by Edith Diaz) conjures the primal, earthy underworld of ancient Aztec myth. Throughout the film, Diaz spouts dire warnings and pearls of wisdom from pagan Indian folklore. At the funeral of an obnoxious pet pooch, Diaz declares—with great drama—that the departed Bojangles is now “in the arms of QUETZALCOATL,” a fierce winged serpent that dwells in the land of the dead. Her upper-crust employers, ignorant and oblivious, smile and nod through their tears. The last scene of the film shows the deceased dog nestled in Mazursky’s arms as the two depart for the dark abyss.

Wagner uses the analogies to make a statement about superficiality, privilege, and the lack of human compassion. In one scene, a prominent “diet doctor” dismisses the controversy about his latest weight loss plan by casually commenting that when the wealthy become obsessed with becoming thin, “some of them are going to die.” In a tragic irony of this life-is-cheap attitude, young costar Rebecca Schaeffer was murdered by a celebrity stalker not long after finishing Scenes, just as she was poised to begin a promising cinematic career.

SCREWTAPE LETTERS, THE The Screwtape Letters is a masterpiece of infernal dialogue penned by the genius C. S. Lewis, author of THE GREAT DIVORCE. Originally written as an advice column in The Guardian newspaper during World War II, Lewis’s letters are communiqués between Screwtape, a DEVIL and the “Undersecretary of the Department of Temptation,” and his nephew Wormwood, a tempter in training. Through these dispatches, Screw-tape gives the young fiend advice on how to corrupt souls to help SATAN reach his goal of “drawing all to himself” in the great below. Through this unusual medium, the author likewise instructs readers to guard against such diabolical tricks.

Lewis opens his book with a brief description of hell, a palce where each being “lives the deadly serious passions of envy, self-importance and resentment” for all eternity. It is a realm where there is no individuality, no dignity, for these things reflect God’s goodness and have no place in the underworld. Hell is a bleak, ugly “Kingdom of Noise” where the dissonant sounds of wailing souls and tortured screams replace music and laughter. Human spirits serve as the “food” upon which DEMONS ravenously feast.

In his letters to Wormwood, Screwtape explains that Satan captures humans by lulling them into putting their own desires and interests ahead of God’s divine plan. A devil’s job is to cause people to “turn their gaze away from Him towards themselves.” This, the dark angel declares, is the way to lead souls to hell, as there are relatively few murderers, rapists, and truly despicable people whose damnation is assured. For most, Screwtape tells Wormwood, “the safest road to hell is the gradual one—the gentle slope” unmarked by glaring atrocities. Humans who devote their lives to “causes,” self-interest, pleasure—confident that they have done nothing vile enough to be condemned—will discover too late that they should have paid more attention to charity and the sacraments.

The Screwtape Letters concludes with an epilogue in hell, where Screwtape is offering a toast at the annual demon graduation dinner. The banquet’s fare consists of the latest crop of human souls, served in such dishes as “Casserole of Adulterers” and “Municipal Authority with Graft Sauce” washed down with a vintage “Pharisee” wine. The devil complains that the quality of the food is not what it used to be—he reminisces on past delicacies of Hitler, Henry VIII, and Casanova—but at least the quantity of damned spirits is steadily increasing. Hell, he declares, has never had “more abundance.”

In closing, Screwtape informs his fellow fiends that sinners are becoming “trash,” scraps of sullied humanity that once would have been thrown to “CERBERUS and the Hellhounds” to gnaw and gobble. These modern souls are not truly evil, just lazy sloths who never bothered with salvation since it did not appease their immediate appetites. They are the children of democracy, wherein everything is a “choice” and no governing moral code is allowed. Such unfettered freedom, Screwtape declares, permits man to “enthrone at the center of his life a good solid, resounding lie.” Modern man does not see his actions as sinful and therefore suffers no guilt, feels no remorse, and seeks no divine forgiveness. After a lifetime of these conscience-numbing decisions, these hollow souls simply trickle, without fanfare, into the pit of hell.

Lewis published his dark satire as a cautionary tale during the late 1950s, when “goodliness” was replacing “Godliness” as a prime objective of humanity. He urges a return to traditional devotion to the Heavenly Father and warns against intellectualism that puts humans at the center of the universe. The Screwtape Letters further suggests that the two most dangerous errors humans make regarding demons is to believe they do not exist, or to become fascinated with them. Falling into either trap, Lewis asserts, will surely take one down the path to hell.

SEASON IN HELL, A Arthur Rimbaud’s autobiographical poetic allegory Une Saison en enfer (A Season in Hell) is among the most fascinating works of literature ever produced. Influenced by images of CHRISTIAN HELL (many works refer to SATAN, Beelzebub, and the sea monster LEVIATHAN), the poems convey a sense of restlessness turned to despair. Rimbaud’s book is odd not only in its content but also in the bizarre story that surrounds its publication. For the young French poet, his short life, marred by scandal and tragedy, was indeed reminiscent of the sufferings of the damned.

In one passage titled “Night in Hell,” Rimbaud likens his wretched life on earth to existence in the netherworld. This image comforts rather than horrifies him, as he feels more companionship with lost souls than with his living contemporaries. He goes so far as to declare that the “delights of the damned” will be far greater when his spirit descends “into the void” where he will finally dwell among peers and escape the harsh critics and stifling restrictions of the human plane. Thus it is not the thought of damnation that tortures Rimbaud, but the insufferable years of life that lead to it.

The author offers a considerably more grisly interpretation of what awaits the condemned in his “Dance of the Hanged Man.” Here, Rimbaud describes the DEMON Beelzebub as a puppeteer who treats humans as toys, “slapping at their heads” to make them “dance, dance” for his pleasure. However these souls are being punished for their inhumanity and cruelty; whereas the author envisions himself as damned for his thoughts rather than his acts. Rimbaud anticipates no such physical torments for intellectual sinners.

Early in life, Rimbaud declared that his only ambition was to write poetry. His disapproving mother, however, tried to force her son into a more “respectable” line of work by forbidding him to read or write any poems and even banned from her house works of the French genius Victor Hugo. But her strategy backfired: Rimbaud ran away to Paris while still in his teens and began a homosexual affair with fellow author Paul Verlaine. Verlaine was both excited and disturbed by the boy’s shocking, vulgar behavior, and at one point he truly believed Rimbaud to be a werewolf. This only added to the poet’s appeal and to his enduring legend.

Rimbaud wrote A Season in Hell between the ages of sixteen and nineteen, then published the work in 1873 at his own expense. The collection laments his status as an outcast who is surely damned and contains haunting images of both the young writer’s troubled past and his grim future in the underworld. Within the composition, Rimbaud speculates that true agony—in this life as well as in the next—is the torment of feeling lonely, isolated, and abandoned. Despondent and brooding, the author distributed several printed copies to friends in Paris, then burned the manuscript and swore never to compose another poem. Rimbaud soon departed to Africa, where he worked as a tradesman until a tumor necessitated the amputation of his leg. He returned to Marseilles, where died in 1891 at age thirty-seven.

Despite this austere start, Rimbaud has since been declared one of the great modern poets and A Season in Hell a masterpiece. He has been elevated to the status of cultural icon in France. In 1991, a gala event was held in Paris to mark the centennial anniversary of the author’s death. The festival included games, banquets, and a nationwide contest for budding poets. To commemorate Rimbaud’s life and his Season in Hell, the French Ministry of Culture even requested that the International Astronomical Union name a star in his honor.

SENTINEL, THE People have been fascinated with the prospect of a passage between earth and hell for millennia. According to Jeffrey Konvitz’s 1974 novel The Sentinel, that gateway exists in a fashionable New York City brownstone. The contemporary fiction explores how this supernatural bridge would be received in the modern climate of disbelief in the great inferno.

Protagonist Allison Parker, a young model grappling with her father’s death and her own failed suicide attempts, finds the apartment of her dreams in a quiet neighborhood on the Upper West Side. But after moving in, Allison begins to have doubts. She is unnerved by an odd assortment of neighbors, including a blind priest who sits day and night staring out the upstairs window, a pair of caustic lesbians, and a senile old woman who seems hauntingly familiar. Hoping to allay her fears, Allison’s coldly “irreligious” boyfriend, Michael, does some investigating, only to find himself drawn further and further into a bizarre supernatural plot.

Michael informs Allison that the brownstone is actually “the bridge over Chaos,” the “connection between the Gates of Hell and the boundaries of earth.” He tells the disbelieving woman that ever since Adam and Eve sinned in the Garden of Eden, a guardian has been posted at this site to “sit and watch for the legions of Hell,” to prevent SATAN from releasing the damned to devour the living. She has been chosen as the next sentinel. When Allison rejects this preposterous theory, Michael erupts, revealing that he knows this because he himself is dead. He has been killed by those trying to protect Allison, and declares, “I’ve been damned to eternal Hell for my sins! I am one of the legion!”

Allison then must decide whether she will surrender herself to this new role, or take her own life. As the sentinel, she would be stripped of her senses, transformed into a hideous hag, and confined to a dark room for the rest of her life, but she would be promised salvation. Should she commit suicide, she would take her place among the condemned souls in eternal torment. The denizens of hell assail her, encouraging Allison to join them in “this infernal pit. Abominable, accurst, the house of woe, and Dungeon of our Tyrant!”

Konvitz’s novel was made into a film in 1976 and joined numerous similar movies describing a mystic portal to the underworld, including THE BEYOND, DEVIL’S DAUGHTER, and THE GATE. But speculation about physical connections to hell go back centuries, to Greek myths about LAKE AVERNUS, early Christian folktales of ST. BRENDAN and the CAVE OF CRUACHAN, and African legends of KITAMBA and UNCAMA.

SERAPIS Serapis offers a rare link between Greek and Egyptian myth. This god of the underworld shows up in CHTHONIC legends from both civilizations. Serapis, who had power over fate and could reward or punish souls of the dead, is often depicted with a dog at his feet. He watches over the dead in a dark land of eternal night.

SHADES According to ancient Greek myth, departed human souls become listless, lethargic spirits called shades. In this faded form, shades journey to the kingdom of HADES, the Greek underworld, where they will spend eternity. There, most suffer no physical punishment but are deprived of the carnal joys of human existence. Human spirits dwelling in the Hebrew SHEOL were thought to be similar murky beings.

Shades describe their shadowy existence in a number of epics, including the AENEID and the ODYSSEY, and appear in such classic works of Western literature as DIVINE COMEDY: THE INFERNO and the recent novel MEMNOCH THE DEVIL. The 1962 cult classic film CARNIVAL OF SOULS likewise depicts spirits as vacuous and robotic, eternally going through the motions of some meaningless dance.

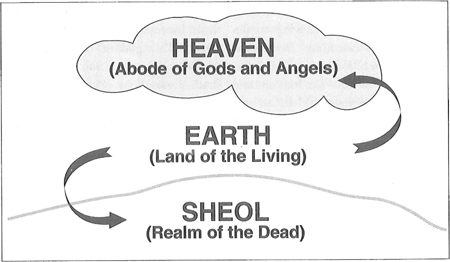

SHEOL Sheol is the underworld of ancient Semitic belief. It is a bleak place of unending monotony where existence continues at a low ebb. Souls in Sheol cannot interact with the gods, nor can they communicate with the living and have little awareness of events outside the forlorn chamber’s borders. Like the Greek underworld of HADES, Sheol is the repository of all departed souls, good and evil.

The living have awareness of heaven and Sheol; the dead are cut off from both upper realms.

Early Jewish prophets absorbed the pagan image of Sheol and used it when referring to the afterlife. Hebrew tradition divided the realm into two sections: one for the wicked who have sinned against God; the second for virtuous spirits who have lived pious and reverent lives. Souls of the just suffer no torments in Sheol, but evil spirits are severely punished. Toward the end of the Hebrew Scriptures, there are hints of escape from the somber realm and restoration to a joyful existence, where the dead receive glory and relief from the hand of God.

The first writings about the realm, dating back to around 700 B.C., refer to the murky underworld as a “land of gloom and deep darkness.” In the Old Testament, Enoch has a vision of Sheol that he declares “chaotic, horrible.” These depictions of the underworld as a crowded, cavernous chasm have derived from pits used as mass graves during this time. Almost everyone, except members of the royal houses, was buried in large communal plots with no individual MEMORIALS, and so it was logical to believe that the next life would be similarly pedestrian.

The ancient concept of Sheol as a tedious prison for damned souls has been largely displaced by modern theories. Many now believe that evil souls will face ANNIHILATION and will be eradicated in the afterlife. Others envision the underworld approximating traditional CHRISTIAN HELL, a place of sheer torment for the wicked. This interpretation evolved in part from Isaiah’s description of Sheol as having “levels,” suggesting that a variety of punishments exist in hell. The prophet warns sinners: “Yet you shall be brought down to Sheol, to the lowest depths of the Pit” (Isa. 14:15).

Particularly wicked souls are thus cast deep into the murky abyss, a place of ultimate agony. This image was embellished and eventually developed into the concept of GEHENNA, a horrible subterranean torture chamber where wicked souls are mercilessly tortured for all eternity.

The ancient hell of Sheol is depicted in numerous works of art and literature, both ancient and contemporary. One of the most recent examples is Anne Rice’s 1995 novel MEMNOCH THE DEVIL, which describes the dreary underworld of Sheol.

SHORT STORIES The nature of the afterlife has long captivated the imagination of writers, with hell being depicted as far more glamorous and fascinating than heaven. Such famous modern authors as Stephen King, Joyce Carol Oates, and CLIVE BARKER have penned short stories speculating on the realm of the damned. Forays into the inferno have been fodder for horror anthologies, articles in issues of Alfred Hitchcock Magazine, TWILIGHT ZONE MAGAZINE, and a host of infernal COMIC BOOKS. Adaptations of CHTHONIC short stories have been televised as episodes of NIGHT GALLERY, TWILIGHT ZONE, and WAY OUT, and have even inspired an assortment of ANIMATED CARTOONS.

Robert Bloch, author of the horror classic Psycho, offers his take on the great below in “That Hell-Bound Train,” a short story written in 1958. The tale follows the misadventures of young Martin, a cynical man who decides that his best chance for happiness in life is in striking a bargain with the DEVIL. In this FAUST update, Martin agrees to ride the express to the underworld after his death in exchange for a chance to stop time at the moment of his greatest happiness. He believes this will actually allow him to cheat the devil, since he will be frozen in time and therefore be protected from death.

But Martin never finds that perfect moment; he keeps thinking that something better is on its way. Finally, he dies without ever having taken his opportunity. He boards the train and joins the damned, all of whom are enjoying one last party before arriving at “the Depot Way Down Yonder,” where their eternity of agony will begin. Suddenly Martin realizes that this is as happy as he has ever been, and he demands that he be allowed to remain on the locomotive forever. The devil reluctantly agrees, and Martin becomes “the new brakeman on that Hell-Bound Train.”

Basil Cooper describes a DREAM MODEL of hell wherein the evil dead must relive the ugliness of their sins in his 1965 “Camera Obscura.” As the tale opens, Mr. Sharsted, a heartless moneylender who puts profit before compassion, goes to the home of Mr. Gingold to demand repayment of a debt. But the mysterious old man keeps changing the subject and eventually brings Sharsted to a dark study to show him his “Victorian toy,” a camera obscura that “gathers a panorama of the town below and transmits it here onto the viewing table.” The camera flashes a full-scale reflection of the town into view, and Gingold starts pointing out homes and businesses that Sharsted brought to ruin with his ruthless foreclosures. Gingold asks the banker if he will not reconsider his “unnecessary and somewhat inhuman” practices. Irritated with this conversation, Sharsted tells the man to mind his own business.

Gingold sighs and tells Sharsted “so be it,” then shows the moneylender out through a door at the back of the house. Sharsted is happy to be away from the enigmatic old gentleman and looks forward to returning with an eviction notice. As he makes his way through town, Sharsted begins to notice that things are not quite right: Buildings that were demolished decades ago are now standing; once-familiar streets become confusing and lead him in circles; and long-dead associates stroll through the village, their rotted faces rimming with maggots. Cooper concludes his story by noting that the camera obscura shows the town “as through the eye of God” and that Sharsted and his ilk are “trapped for eternity, stumbling, weeping, swearing” in their own “private Hell.” This chilling story was later adapted into a screenplay for the television series Night Gallery.

Ancient mythical descriptions of the netherworld have likewise made their way into contemporary short stories. Adobe James’s “The Road to Mictlantecutli,” also written in the early 1960s, conjures images of MICTLAN, the underworld of Aztec legend. When Morgan, the story’s cop-killing villain, wrecks his car in the Mexican desert, he is approached by two very different figures. The first is a quiet priest who finds Morgan at the scene of the accident and offers to see him to safety. As they make their way through the night, a beautiful woman on a sleek stallion rides up and invites Morgan to accompany her to “Mictlantecutli’s ranch,” just down the road. The cleric begs Morgan to remain with him, declaring that “she is evil. Evil personified.” Morgan, hoping that the brazen girl might offer more than just a horseback ride, considers this a “recommendation.” He rides off with her, ignoring the priest’s warning that “I am your last chance.”

On the way to the ranch, the pair stops for a violent sexual encounter beneath the stars. Afterward, the girl tells Morgan she wants to show him something before they reach Mictlantecutli’s. They ride back to the site of the accident, and Morgan is horrified to see his lacerated corpse—half devoured by vultures—behind the wheel. There on the roadside is the priest. “Help me!” Morgan shouts. But the cleric replies he cannot. “You have embraced evil; you have made your last earthly choice.” Laughing, the beautiful girl transforms into a rotting cadaver as she takes Morgan to meet Mictlantecutli, also known as “Diablo, SATAN, DEVIL, LUCIFER, MEPHISTOPHELES.”

The most commercially successful modern writer of the genre, Stephen King, has offered several shorts dealing with the topic of afterlife agony. In “You Know They Got a Hell of a Band,” a young couple takes a wrong turn and winds up in a supernatural village where they become eternal captives at a rock and roll concert that never ends. His “Mrs. Todd’s Shortcut” sends characters down a road that leads to a woods where animated trees grab at passersby and monstrous creatures “not of this world” make frightening roadkill.

Contemporary short story writers continue to draw inspiration from the ominous underworld. Even in the modern world of religious cynicism, hell continues to fire the human imagination.

SHOBARI WAKA Shobari Waka is the hell of the Yanomamo Indians of Brazil and Venezuela. In this pit, the damned burn for all eternity. Wadawadariwa, a wise spirit, questions souls on their afterlife journey to determine whether they should be sent to Shobari Waka or to paradise. Those who reveal themselves as greedy, petty, or cruel are damned to the bitter underworld for everlasting punishment.

SHOCK ’EM DEAD 1990 horror film Shock ’Em Dead blends the FAUST legend with rumors about SATAN worship in HEAVY METAL MUSIC. Aldo Ray stars as the desperate musician who sells his soul in exchange for superstar status in the world of rock and roll. He consummates the bargain by touring hell and seeing the “delights” of the damned. In one particularly frightening scene, Ray is given three voluptuous lovers to satisfy him sexually, but when he looks into the mirror he sees reflected a trio of decaying hags. Other unpleasant surprises include discovering that food has become inedible and that he now must sustain on a diet of human flesh.

The hell of Shock ’Em Dead is an orgy of carnal excesses that ultimately delivers far more pain than pleasure. Similar cinematic depictions of the underworld include HELLRAISER, HIGHWAY TO HELL, and NIGHT ANGEL.

SIGNORELLI, LUCA Tuscan artist Luca Signorelli (c. 1441–1523) drew inspiration from the images of CHRISTIAN HELL for his creative works. He frequently depicts the underworld as the place of unrelenting torture and unspeakable suffering described in the Bible. But Signorelli’s interpretations of the dark abyss differ greatly from those of his contemporaries and show particular genius and innovation. Unlike other masters, he shows a hell devoid of flames, fire, or any harsh landscape. His DEMONS differ, too, in that they are almost beautiful—created with exquisite muscle tone and brilliant color. Thus his underworld vision introduces the concept of spiritual and psychological agony to the medium.

Signorelli’s portrayal incorporates the belief that these fiends of hell were once angels of God, lovely and alluring, before their rebellion and fall from grace. The reality of having to accept their new status as beasts of the pit adds a psychological dimension to the horrors of hell. His THE DAMNED CONSIGNED TO HELL shows naked sinners being led away in chains by grinning winged monsters. The bodies of the damned are corralled into an impossibly crowded chasm to be heaped upon one another in a grisly landfill of human remains. A horde of orange and green demons is shown gleefully strangling, biting, and clawing, these condemned souls.

Drawing of Signorelli’s vision of the creation of hell. ART TODAY

Signorelli’s creations were a departure from traditional depictions of hell as a fiery pit of flames and beastlike fiends. By showing the fallen angels as beautiful, he stirs an element of sorrow at the unutterable loss of divine splendor, which renders the sufferings of hell more poignant and chilling. The artist’s contributions to CHURCH ART AND ARCHITECTURE also include a LAST JUDGMENT scene featuring the Antichrist as well as hell, purgatory, and heaven. His visions are adapted from REVELATION, which foretells a fearsome apocalypse that will one day befall humankind.

SIN EATER In seventeenth-century Britain, the rich hired a sin eater to save the souls of their departed loved ones from hell. When a person died, a loaf of bread or pitcher of milk or wine was placed over the heart of the corpse to “absorb” the body’s evil. The sin eater then consumed the tainted food or drink, thus accepting the guilt and punishment that were consequences of those sins. Ritual completed, the departed soul supposedly proceeded to the afterlife without fear of damnation.

Most villages had a designated sin eater, usually an old man with no other means of support. Others believed that the sin eater must be a total stranger with no ties to the deceased or his kin. During the height of this custom, nefarious cads would trick others into ingesting sins by giving contaminated bread or wine to beggars or passersby without revealing that it had been used to absorb a dead person’s iniquity. This covert proffer was also used to exact revenge on enemies, since those who participated in this ritual truly believed that those who ingested sullied food would have to atone for another’s wickedness.

The practice of hiring a sin eater was condemned by the Christian church and eventually lost popularity. Within a few decades, the very idea of hell and damnation was being called “ridiculous” and “superstitious” by religious scholars and secular philosophers, making the practice obsolete.

SIRAT Muslim legend tells of the great Sirat (Islamic for “road”), a path that serves as a bridge over hell. The supernatural pathway is “finer than a hair and sharper than a sword,” and departed spirits must navigate the narrow road in order to reach paradise. Faithful souls will reach the other side safely, but infidels will fall into JAHANNAM (hell) below. Sirat is frequently associated with CHINVAT BRIDGE, a similar passageway described in ancient Persian folklore.

SISYPHUS Sisyphus, King of Corinth, is among the damned who suffer in TARTARUS, the lowest realm of the Greek mythic underworld HADES. He earned this punishment by trying to outsmart death and trying to blackmail Zeus, head of the Greek pantheon.

Sisyphus witnesses Zeus raping the nymph Aegina, daughter of Asopus, and threatens to tell the young maiden’s father about the crime. Enraged, Zeus sends Thanatos (Death) to silence Sisyphus by taking him to the underworld, but the clever king ambushes Thanatos and binds him in heavy chains. Zeus dispatches Ares, god of war, to free Thanatos. However, by this time Sisyphus has devised another plan for evading his fate. He instructs his wife that if he should die, she must not offer the customary funeral sacrifices. Thanatos slays Sisyphus, and, as instructed, Sisyphus’s wife buries him without conducting the proper rites.

When Sisyphus comes to the underworld, King Hades and Queen PERSEPHONE refuse him entrance, since he has not offered them traditional tribute. Sisyphus convinces the deities to let him ascend to the upper-world to take care of the matter himself. They agree and release Sisyphus, who has no intention of returning to Hades. He manages to elude both Thanatos and Zeus for many decades before dying a second time.

This time, when Sisyphus arrives in the underworld, Zeus is ready. He devises a cruel punishment for the king: He damns Sisyphus to push a huge bolder up a hill only to have it immediately roll back down again. Sisyphus will be granted no rest in the afterlife until this impossible feat is accomplished.

The legend of Sisyphus inspired poems and plays and was immortalized on canvas by Venetian master Titian.

SIZE OF HELL Philosophers have been speculating about the size of hell for centuries. Using passages from the Bible, ancient legends, and simple guesswork, scholars have sought to determine the exact dimensions of the realm of the damned.

In “CHRIST AND SATAN,” a Christian poem dating back to the 1100s, determining the area of hell is a major plot point. After Satan fails to tempt Christ in the desert, the DEVIL is ordered to measure his kingdom. The Savior demands that Satan go back to the underworld and crawl hell’s length and breadth on his hands and knees through the foul-smelling darkness, then report on its size. Satan does so and declares that the underworld extends for 100,000 miles. Though an imaginative piece of prose, the measurement from “Christ and Satan” has been universally dismissed as a “colorful” but baseless concept. But the work attests to humanity’s fascination with the subject of hell’s perimeters.

Defining the scope of hell has received serious treatment from noteworthy Christian intellectuals as well. The most prominent preacher of the fourteenth century, Berthold of Regensburg, claimed that only one person in 100,000 would be saved. The rest would bake in an unquenchable fire for all eternity. This assertion has been largely condemned, however, not only for its pessimism but because it would necessitate an enormous place for the damned to reside.

Influenced by both the frivolous and somber estimations of the devil’s kingdom, sixteenth-century scientist Galileo took up the concept during his early studies. He used specifications from Dante’s DIVINE COMEDY: THE INFERNO to calculate the distance between earth, heaven, and hell as well as the dimensions of the underworld itself. And though his treatise was simply musing, his theories about mortality, the afterlife, and humanity’s place in the universe are believed to have influenced numerous artists, including Milton (author of PARADISE LOST) who visited Galileo in Italy before writing his masterpiece.

Today, most people consider determining the exact size of hell a moot issue. Since hell is a spiritual dimension, physical measurements are meaningless and do nothing to amplify or ease the suffering of the damned.

SOVI Sovi, hero of folktales from the Baltic regions, is said to have seen firsthand the grisly terrors of the underworld. After hearing his tale, many villagers insisted on cremating their dead in hopes of escaping the spectacle he describes.

According to the story, Sovi kills a wild pig and eats the boar’s nine spleens. After ingesting this feast, Sovi and his sons descend into hell and witness its many horrors. The men report seeing “worms and reptiles eat” the flesh of the damned. Swarms of “bees and mosquitoes sting” the souls who scurry about, unable to find cover from the piercing pests. When he returns to the land of the living, Sovi declares that only destruction of the corpse could ensure peace after death. Many superstitious clerics agreed, saying they could “see” the soul rise and ride off on a horse as the funeral pyre burned.

STORM, HOWARD Howard Storm is among the estimated eleven million people who have had a NEAR-DEATH EXPERIENCE, a term commonly applied to supernatural encounters of patients who survive clinical death and retain memories of their “otherworld” adventures. Unlike most reported incidents, however, Storm’s experience was not a joyous trek through a tunnel of “bright light” to a place of incredible peace; it was a horrifying descent into hell.

Storm reports that before the incident, he was enjoying a comfortable life as a respected college professor. He did not take religion seriously and scoffed at the notion of eternal damnation. But after a near-fatal heart attack, Storm experienced clinical death and found himself cast into the underworld—a horrid, dark place of sheer terror. He repeatedly pleaded, “Jesus, save me!” and was soon revived by physicians.

The memory of that terrifying realm haunted him constantly. Unable to cope with the images of that horror, Storm began studying Christianity. As his knowledge increased, he saw the need to make radical changes in his lifestyle. Storm completed his theological studies and became an ordained minister. He now devotes his life to preaching the message of spiritualism and acceptance of Christ to avoid damnation. Part of his ministry is retelling his story and warning others of the reality of hell.

Rev. Storm also believes that there are thousands of people who have had similar infernal experiences—“dying” and finding themselves in hell—but seldom share them because of the negative implications. He suggests that there are many more of these than there are positive near-death experiences. The message in all this, he says, is to prepare for the day of final judgment. Hell is real, he warns, and most people who end up there will not get the chance to come back and repent.

Storm’s incredible story has been recounted in numerous magazine articles, books, and on television talk shows. His supernatural journey was also profiled on a 1996 episode of Unsolved Mysteries.

STAY TUNED Hell is an endless lineup of awful television programs according to the 1992 film Stay Tuned. The comedy stars John Ritter and Pam Dawber as a suburban couple who buy a big-screen TV and satellite dish from a fast-talking salesman for Hellvision. But when couch potato Ritter tunes in, he discovers that the new set receives only bizarre shows he has never heard of, such as I Love LUCIFER, Golden Ghouls, My Three Sons of Bitches, Duane’s Underworld, and Beverly Hills 90666. The set also receives infernal MUSIC VIDEOS too atrocious for Music Television. When Ritter investigates the mysterious satellite, he is pulled into the underworld of abysmal TV.

Dawber unwittingly joins her husband in the inferno, and the two are told by SATAN (played by Jeffrey Jones) that there is only one way to escape eternal damnation. They must survive in this electronic hell for twenty-four hours, after which time they will be restored to life. During their stay in the broadcast inferno, they will be hunted and assailed by villains from a variety of hell’s television shows. If they are killed in any of the programs, their souls will be “canceled” and their fate sealed. Jones will observe their progress from his high-tech studio in hell proper, where the touch of a button on the diabolical remote control sends spirits into ever-evolving horrors.

STYX The river Styx separates the realms of the living and the dead according to ancient Greek myth. When a person dies, his or her SHADE (spirit) drifts to the riverbank and awaits CHARON, a ghostly ferryman who will transport the souls to the underworld kingdom of HADES.

The Styx is an actual river in Greece, believed to have metaphysical implications because its waters disappear underground. Scholars eventually revised their theories and came to believe that the entrance to the underworld is actually at LAKE AVERNUS in northern Italy. But the river Styx remains a mysterious and enduring symbol of the mythical underworld.

The Styx has been included in such literary works as the AENEID, the ODYSSEY, and Dante’s DIVINE COMEDY: THE INFERNO. It has been further immortalized in a number of other works, including poems, paintings, operas, and films.

SUCCUBUS The succubus is the female DEMON of Jewish, Christian, and Islamic folklore who seeks to destroy human souls by tempting them with sexual images while they sleep. Some succubi could actually engage in intercourse with their sleeping prey. The succubus is the counterpart of the male INCUBUS, a fiend who preys upon women. Once a man succumbs to the “dream seduction,” his damnation to hell is believed to be sealed.

The 1990 film NIGHT ANGEL features the modern adventures of the succubus LILITH. Lilith is a mythic DEMON who had been created to be mother of the human race but who chose to copulate with the DEVIL instead. After this lurid union, Lilith joined the minions of hell in vowing to corrupt mankind through sexual lust.

SUNNIULF OF RANDAU One of the most intriguing examples of VISION LITERATURE is the account of Sunniulf of Randau’s visit to hell. Sunniulf’s version of this journey was recorded by Bishop Gregory of Tours in his History of the Franks. According to the story, Sunniulf, a sixth-century monk and abbot of Randau, was reminded of what happens to immoral clerics through a terrifying underworld adventure.

The abbot, failing in his faith and doubting the goodness of God, falls into a deep trance, and his spirit is taken to the edge of a fermenting river. The riverbank is crammed with thousands of people, all trying to cross a narrow bridge that leads to a gleaming city of light. Sunniulf is warned that only clerics who have lived lives of virtue can pass. Others will fall into the muck and sink according to the depravity of their sins. Sunniulf watches as several souls try to make it across the bridge, only to slip into the filth. The worst among them sinks up to his neck in the foul bilge. Sunniulf worries that he might slide even deeper and is seized with indescribable terror.

But before Sunniulf can attempt to cross, he is delivered back to his body. When he awakes he asks for a confessor, shares his vision, and renews his vow to live a holy life. Skeptics discounted his story as the ravings of a very sick man, but countless others found inspiration in his tale—and in his candor at admitting his sins. Sunniulf’s account was especially compelling, since, as a priest, most believers assumed he would be assured of salvation. If even a man of God could face damnation, then they, too, should take heed and amend their lives.

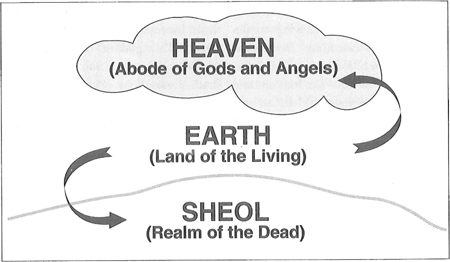

SWAHILI HELL According to African Swahili belief, hell is a deep abyss below the surface of the earth into which the damned are cast. It is the seventh thing God created and accordingly has seven descending levels. The worst sinners, those believed beyond hope of salvation, occupy the lowest realm, which is an icy place of unendurable cold. (Departed souls of moderately evil people could be sent to the sixth circle below the earth for punishment. These spirits had some hope of eventual salvation.)

Universe of Swahili myth.

The influence of eighth-century Arab traders is evident in the depiction of Swahili hell. As in the Islam faith, the deepest pit of the underworld is ruled by IBLIS (a harsh DEMON), who metes out punishment to his accursed subjects. Traveling merchants from Muslim countries also brought notions of JAHANNAM, the hell of Muslim belief. Their images of a horrible underworld of torment became mingled with indigenous concepts of afterlife justice. The result is a dark realm that features components of both faiths.

SWASTIKA Long before the Nazis appropriated this mythical symbol, the swastika had been a powerful icon representing the perpetual life cycle. Sometimes referred to as the “sun wheel,” swastikas have been found in cultures throughout the world dating as far back as the eighth century B.C. From the societies of ancient Greece to Native Americans, this mysterious image has been respected, revered, and even feared.

In the Jain religion, an Asian religion that includes doctrines of a treacherous underworld, the swastika is among the most hallowed symbols. (The word swastika is derived from the Sanskrit svasti meaning “fortune, luck, well-being.”) Its central point stands for life, and the four branches represent the possible fates of a departed soul: It could be condemned to hell, be elevated to the status of a god, be reincarnated in human form, or be reborn as an animal. Taken as a whole, the swastika forms a wheel that depicts perfect being (siddha), from which no rebirth is necessary.

According to the teachings of Jainism, damned souls must endure a myriad of tortures in hell. These include impalement, mutilation, and dismemberment meted out in direct relation to the spirit’s offenses. Grisly as the inferno is, condemned souls could take solace in the fact that damnation is only temporary, since after all sins are purged through pain, the soul is reborn and resumes the life cycle. Thus the swastika, the wheel of being, continues in motion.

It is this ominous mystic power that intrigued Adolf Hitler. Being highly superstitious, he equated the swastika with immortality and developed the hakenkreuz, meaning “hooked cross,” as the icon for his troops. The symbol was officially adopted by the Nazi party in 1935 and emblazoned upon Nazi flags, armbands, and banners. Hitler believed that troops marching under the swastika would be unstoppable and that his “perfect society” would endure forever.

Today, the swastika has come to be identified with Nazism, anti-Semitism, and white supremacist agendas. It is commonly found on the propaganda and MILITARY INSIGNIA of such groups. Because of this irreverent and emotionally charged connotation, the swastika also has become an icon of HEAVY METAL MUSIC groups wanting to advertise their contempt of traditional mores.

SWEDENBORG, EMANUEL Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772), a self-proclaimed “seer” and philosopher, wrote Heaven and Hell in the late 1750s. In it he describes his “experiences” with heaven, hell, angels, and DEMONS. Born to Swedish nobility, this son of a prominent Protestant bishop reported having supernatural visions beginning around 1744. Troubled by these sometimes disturbing images, Swedenborg began reading the Bible for insight in interpreting the otherworldly information.

According to Swedenborg’s divination, the Christian messiah Jesus never actually became a man. He only disguised his divinity in human form to help the “fallen sons of Adam” find their way back to God. The sin in the Garden of Eden signaled man’s desire to put himself before the Almighty, and Christ’s mission was to return focus to the Father. His role was not to “redeem” humankind but to identify a system whereby each person could save himself or herself. Having accomplished this, Jesus shows that all humans can one day be “glorified” as he is, provided they climb the “staircase” to heaven rather than descend to hell by rejecting God’s love.

During his career, Swedenborg wrote sixteen extensive tomes about his visions. In these, he claims to have visited heaven, hell, and even other planets. His Concerning the Earths in Our Solar System offers detailed descriptions of humanlike creatures on the moon, Venus, and Mars. His most complex work recounts an actual tour (in the tradition of Dante’s DIVINE COMEDY: THE INFERNO) of paradise and the abyss, which he reaches via a brass elevator. After Swedenborg’s death, these texts became the basis for the Church of the New Jerusalem, which claims to “complete” rather than contradict other Christian doctrines.

According to Swedenborg’s theories, when a person dies, the soul enters a “spirit world” where it continues to eat, drink, sleep, interact with loved ones, and perform other human functions. Most of the newly deceased do not even realize that they are dead. This intermediate realm becomes a place of learning where spirits develop and grow—with the assistance of angels—before ascending to paradise.

Those unwilling to progress receive no such angelic guidance and become confused and lost. Stubborn and uncooperative, they find only paths to hell as they flee God and try to distance themselves from the Almighty. (Swedenborg stresses that souls are not condemned by a celestial judge but choose damnation through their refusal to improve themselves.) Spirits who have chosen this fate suffer mental and emotional pain rather than physical agony. They become trapped in their own limited, flawed, unfulfilled existence where damned souls prey upon one another in the most vile ways. He describes a typical scene in the abyss: “In the streets and lanes are committed robberies and depredations. In some hells are brothels disgusting to behold, being filled with all sorts of filth and excrement.”

Swedenborg’s teachings influenced the works of many modern artists, including the Irish poet WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS and the philosopher WILLIAM BLAKE. Despite his widespread popularity, Swedenborg also received a great deal of criticism from those who considered his “visions” to be hallucinations or even outright fabrications. His response to these detractors was simply, “I care not, since I have seen, lived and felt” these incredible experiences.