VAMPIRES Vampires, “undead” creatures with supernatural attributes, are tenets of many legends and myth systems from across the globe. Called “living damnation,” vampiric existence is detestable to all, even to the vampires themselves. They are accursed souls, condemned and despised both in this world and the next.

Tales of these gruesome fiends date back centuries, to the oldest known civilizations. Strigoe, an ancient Roman god, was believed to prey upon infants, sneaking into nurseries in the midnight hours to drain the blood of children. Chonchon, the vampire of Chilean Indian belief, could fly using its oversized ears as wings. Greek vampires, called vrykolakas, could be used by evil DEMONS to terrorize the living. They are depicted as swollen, bloated bodies damned to a ghoulish existence of wandering eternity to finish unsettled business or as a punishment for unforgivable sins. The Maya fear Camazotz, a vampire deity depicted with a razor in one hand and a wilting victim in the other. And according to one Japanese myth, a vampire in the form of a cat launched a wave of bloody violence against the court of a legendary Prince of Nabeshima.

Throughout history, vampirism has often been linked to femininity. The Irish deargdue are seductive life-stealing vixens, human counterparts to the demonic SUCCUBUS. In Scotland, sensuous baobhan sith lurk in the mountains and move in shadows stalking their mortal prey. And Malayan mothers who die in childbirth are believed to become langhui, vampiric spirits who rise from the grave to suck dry the blood of newborn babies. (The word vamp—coined to refer to an unscrupulous woman who uses sexuality to manipulate and exploit men—is derived from the word vampire.)

Pre-Columbian South American vampire demon. ART TODAY

Belief in vampires has resulted in other traditions as well. The practice of holding a wake, where loved ones stand guard over a newly deceased corpse for several days originated out of fear of vampirism. In some South American tribes, the living periodically exhume the bones of their loved ones, rinse them in wine, and have them blessed and reburied to guarantee the deceased a restful afterlife. Another way to ensure that corpses do not rise again is to fasten them to the ground with thick poles. In Western cultures, wooden stakes are considered most effective, as Christianity teaches that Jesus was crucified on a cross of wood. Since he conquered death and overpowered hell, wooden stakes are thus believed to have great supernatural as well as physical strength.

This mingling of religious hysteria with pagan superstition made vampires as fascinating as they were fearsome. During the 1800s, literature exploring vampirism became quite popular. Such masters as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (author of the quintessential FAUST drama), Lord Byron, and CHARLES BAUDELAIRE composed brilliant works inspired by these diabolical fiends. By far, the most famous vampire of English literature is Irish novelist Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Stoker’s book is based on tales of the medieval Romanian sadist Prince Vlad Tepes, better known as Vlad the Impaler, who terrorized thousands with his brutal tortures, dismemberments, and mutilations. (The name Drakula is Romanian for “son of the devil.”) Since its publication in 1897, Dracula has captivated the collective imagination and become synonymous with the word vampire.

Fascination with vampires and their gory practices remains steady. The undead creatures have inspired hundreds of novels, stage plays, artworks, movies, and other creative endeavors. A television series entitled Forever Knight features a penitent vampire who seeks to atone for eight centuries of killings by working as a policeman in modern Toronto. Contemporary novelist Anne Rice has built a career on relating the adventures of Lestat, a stylish New Orleans vampire. The last in this series, MEMNOCH THE DEVIL, sends Lestat to hell for a firsthand look at what SATAN has to offer. And cinematic adaptations of these bloodsuckers run the gamut from classic chillers such as Nosferatu and Dracula to modern comedic satires Dead and Loving It and A Vampire in Brooklyn.

Vampires are also favorite subjects for MOVIE MERCHANDISING, TRADING CARDS, and FANTASY ART.

“VATHEK” William Beckford completed his tale “Vathek,” an exotic version of the FAUST tale, in 1785 after struggling with it for more than three years. By that time the author had become an eccentric nobleman obsessed with the occult. Beckford turned his massive estate of Fonthill Abbey into his own private hell, complete with hideously deformed servants. He also erected a wall around his Gothic mansion and six thousand landscaped acres that ran for fifteen miles, stood twelve feet high, and was topped with sharp spikes. Inside the gold-encrusted gates, Beckford kept sixty fireplaces burning at all times, even through the summertime.

Beckford retreated to this fortress after being shunned by decent society. His life had been marred by numerous scandals involving illicit business dealings, dabblings in witchcraft, and allegations of homosexual orgies. In his exile, he became fascinated with Arabian legends, especially tales of magic. From this odd synthesis came “Vathek,” which many critics still consider the finest “Oriental tale” originally written in a European language.

The story describes the atrocities of a wicked caliph named Vathek who is fixated on indulging in sensual pleasure. Unable to satisfy his wanton cravings through excessive perversion, he becomes obsessed with gaining “forbidden knowledge” and enters into a deal with Giaour, an earthbound DEVIL. Giaour promises to deliver to Vathek wealth, power, and wisdom in exchange for his soul. Vathek agrees and is shown the “Palace of Subterranean Fire” below the earth in a “vast black chasm, a portal of ebony.”

Vathek witnesses the horrors of hell but is unmoved by them. Despite the screams of agony and maniacal rages of the damned, Vathek believes that his soul will not suffer in the underworld, for it is already steeped in evil. The despicable caliph then meets Eblis (IBLIS), ruler of hell, who offers Vathek acceptance into the “fortress of Aherman [AHRIMAN].” Vathek shows his allegiance through an offering of “the blood of fifty children,” all sons and daughters of those who loved and trusted him. He slaughters the innocents without a moment of remorse.

After his fate has been sealed, the condemned tell Vathek of their horrible torment. Many lament that for a few fleeting moments of pleasure, they now suffer unending agony. They bemoan losing “the most precious gift of Heaven: Hope.” Dejected, Vathek joins the “accursed multitude … to wander in an eternity of unabating anguish.” Too late, he realizes that hell is not a glamorous realm of unlimited indulgence but an “abode of vengeance and despair.” The story ends with a warning against the petty pursuit of “empty pomp and forbidden power.”

VAULT OF HORROR Vault of Horror is the follow-up to the 1972 horror film TALES FROM THE CRYPT. Like its precursor, Vault of Horror uses stories originally published in COMIC BOOKS of the 1950s to depict hell as a place of retribution where sinners can no longer escape justice. The film relies heavily on the DREAM MODEL of the afterlife, wherein souls spend eternity engrossed in memories of the past. Suffering for the damned is being trapped in the wretched recollections of their own hateful acts.

Vault of Horror opens as five passengers board an elevator that suddenly plummets to the basement. When the car crashes, all five are surprised to discover that no one has been hurt. The doors open to a comfortable room. They enter, sit down, and begin discussing their recurring dreams. But the nightmares they describe are dark and treacherous: A “neat freak” imagines driving his wife mad with his obsession; a magician kills a competitor for the “perfect illusion”; a brother slaughters his sister to gain the family inheritance. Each person offers a grisly tale of violence and deceit.

Disgusted with their companions and with their own ghastly images, the five try to leave but find that the elevator is not working. Their fate is then revealed: All have in fact been killed in the accident, and the “dreams” were actual events that resulted in their damnation. As punishment, these condemned souls must remain together for eternity recalling their atrocious crimes.

VICENTE, GIL Gil Vicente, (1470–1536), considered the “father of Portuguese drama,” was among the first poets to write original religious plays in Portuguese. Vicente’s works bear strong resemblance to traditional MORALITY PLAYS yet add a touch of humanity and satire to teach religious lessons. His most famous work, a trilogy of dramas titled The Ships of Hell, Purgatory and Glory, has been called “the Portuguese DIVINE COMEDY.” Like Dante’s masterpiece, Vicente’s Ships, written in 1517, describes the afterlife in lyric poetry.

VIRAF Legendary holy man Artay Viraf (c. 1000 B.C.) was reputed to be among the most virtuous men who ever lived. A text dating back to around 800 B.C. tells of his divine tasks, one of which was to discover knowledge through mysticism. In his quest to learn about the “other world,” Viraf spent much of his time in trancelike meditation, often aided by hashish and other mind-altering drugs. Using this method, Viraf traveled out of body, investigating the supernatural and pursuing ultimate truth. In one such trance, he set out to explore the conditions of the underworld by paying a visit to hell.

According to Viraf, hell was a horribly desolate place like the inside of the grave, “cold and icy” and polluted by an unbearably putrid “dryness and stench.” Beyond the immediate grave was a narrow chasm enveloped by blackness where “noxious beasts tore and worried at the damned.” But this was not the worst of hell; Viraf was shaken by the numbing solitude of the realm, for “each soul thought ‘I am alone.’” He determined that the true torture of damnation was the crushing solitude each soul experiences, being eternally isolated from his fellows.

However horrible, this suffering would be only temporary. Viraf’s tale was eventually combined with the teachings of ZOROASTRIANISM, which teaches that at the end of time there will be an apocalyptic battle in which the underworld will be vaporized. Repentant sinners and souls in LIMBO will ascend to heaven after this LAST JUDGMENT. Paradise will be located on a renewed earth, where body and soul will be reunited for an eternity of spiritual and sensual pleasures. Those who refuse to renounce there evil ways, however, will face ANNIHILATION and be eradicated from existence.

VIRGIN MARY Roman Catholics believe that the Virgin Mary, mother of the Christian redeemer Jesus Christ, has the power to save doomed souls from hell. Her assistance is sought both for the living, that they may amend their lives, and for the dead who are languishing in PURGATORIAL HELL. The Hail Mary, a prayer to the Virgin, asks: “Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners, now and at the hour of our death.”

Some legends go even further, claiming that she can journey to hell to retrieve damned souls. Writing about the Virgin Mary, Saint Bonaventure notes, “He who honors thee will be far from damnation.” There are numerous tales about iniquitous men and women being saved from hell through her intercession. A ninth-century account recalls a deacon named Adelman who died and “had seen Hell, to which he was condemned.” But through Mary’s urging, the deacon was restored to life to atone for his sins.

Even more extraordinary is the story of a Roman citizen who had died in a state of mortal sin. Years later, as Emperor Sigismund was moving his armies through the Alps, the man’s skeleton came to life and asked for a priest. He told the astonished troops that Mary, whom he had always revered, had obtained for him this final chance at salvation.

A similar tale originates in early seventeenth-century Belgium. Two young men had been enjoying a night of drinking and debauchery, when one (by the name of Richard) left the party and went home. He mumbled his prayers to the Mother of God—albeit halfheartedly—before falling asleep. That night, Richard was suddenly awakened by a hideous monster who claimed to be his friend. “A DEVIL came and strangled me,” his companion said. “My body is in the street and my soul in Hell!” Richard’s deceased compatriot then opened his coat, and Richard could see the serpents and flames that tortured the man. Before returning to the inferno, the damned soul told Richard that it was his devotion to the Virgin that had saved him from the same fate.

The Virgin Mary has also been linked to visions of hell granted as warnings against falling to temptation. One of the most famous occurred in Fátima, Portugal, in 1917. Mary appeared to three young shepherd children and asked them to pray the rosary (a series of prayers commemorating Mary’s role in Christ’s life) over a period of several months. During one visit, she gave the oldest girl, LUCIA DOS SANTOS, a horrifying glimpse of the damned suffering in hell. The images were so disturbing that Lucia later stated that if the vision had lasted even a moment longer, it would have killed her.

A prayer card of Mother of Perpetual Help includes verbiage asking the Virgin Mary for protection from hell. COURTESY OF THE REDEMPTIONIST FATHERS

Because of her significance in Christendom, Mary has become a prominent figure in Christian literature and drama. She is included as mediator in many variations of the FAUST legend and in MYSTERY PLAYS and MORALITY PLAYS. The Virgin is also frequently depicted in CHURCH ART AND ARCHITECTURE, often shown beside Jesus in renderings of the LAST JUDGMENT.

VISION LITERATURE Vision literature is a large, diverse body of works recounting the adventures of people who have “witnessed” afterlife events firsthand. Most originate from medieval Europe, although records of these supernatural journeys are also found in African, Asian, and North, Central, and South American Indian cultures. There are even contemporary examples of vision literature written in the past decade. These various texts share one thing in common: They are presented as fact, not fiction, and are fiercely defended by their authors as legitimate reports of the next world.

One of the oldest cautionary tales of this type involves a Burmese Buddhist monk who has become corrupt and self-indulgent. Upon “dying,” he is damned to hell for his sins. There, the monk is immersed up to his chin in human feces while his face is gnawed by huge, toothy worms. He also witnesses other tortures, seeing his damned brethren being beaten, burned, and put through a gamut of thorny tasks that reduce them to mere ribbons of blood. The fallen monk offered his disturbing story as a warning to others tempted to abandon their vows.

The African legend of Angolan King KITAMBA’s expedition to the land of the dead presents a very different message about mortality. When the king loses his beloved wife, Muhongo, he forces the entire village into mourning. Months pass, and Kitamba’s subjects want to return to their former traditions of celebration, merriment, and festivities. Kitamba refuses to retract the order until a medicine man travels to the underworld to seek Muhongo’s advice. The deceased queen tells him to relay the message that although the underworld is dark and monotonous, she not in any physical pain. When Kitamba hears this, he ends the mourning and encourages his people to enjoy life while it lasts.

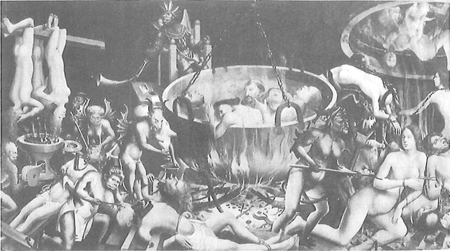

The Inferno, a sixteenth-century Portuguese painting, depicts many of the horrors described in Christian vision literature. GIRAUDON/ART RESOURCE, N.Y.

Vision literature from Christendom invariably stresses the need to reform and repent. Examples of this include the accounts of TUNDAL, FURSEUS, ALBERIC OF SETTAFRATI, BEDE, ADAMNAN, and DRITHELM, all of which describe horrible tortures inflicted on the damned. Torments range from being devoured by dogs to being forced to climb a ladder of razors barefoot. Most of these visions were experienced by peasants. However, since commoners were illiterate, clerics were usually asked to transcribe the tales. Colorful illustrations were often added to enhance the images, and these accounts were then widely circulated throughout Europe and its colonies.

These frightening medieval stories have a number of shared elements. The majority feature biblical DEMONS—SATAN, the DEVIL, BELIAL, LUCIFER—and a variety of lesser fiends as overlords of the abyss. Another common component is the inclusion of a supernatural “guide” to serve as escort and narrator for the tour of hell. Drithelm is accompanied on his afterlife journey by an angel, Furseus by a contingent of heavenly hosts. Christ’s apostle and first pope of the Roman Catholic church, St. Peter, serves as Alberic of Settafrati’s protector and mentor in the underworld. Other accounts refer to “benevolent spirits” and “steadfast shepherds” who usher human souls through the realm of the damned.

The popularity of vision literature peaked toward the end of the Middle Ages. By the time the genre went into decline in the fourteenth century, literally hundreds of people had claimed to have visited heaven, hell, and purgatory while “dead,” only to be revived to tell their tales. Those who did not personally experience this phenomenon were eager to hear others’ testimony. Sermons based on visions were commonplace: Priests drew on the riveting images for inspiration when preaching repentance, describing the afterlife, or trying to convert the unbaptized. Vision literature became so popular that many churchgoers began attending services just to hear the dynamic chronicles of hell.

The demise of vision literature can be attributed to several factors. First, the proliferation of these alleged journeys led to growing skepticism about their authenticity. Under the weight of so many conflicting and increasingly flamboyant accounts of hell’s conditions, the fad eventually collapsed upon itself. This was hastened by scholarly debate over whether souls would be adjudicated immediately upon death, or would await the LAST JUDGMENT before entering heaven or hell. Many Christian philosophers taught that “visions” of spirits in the afterlife were impossible, since human souls would “sleep in Christ” until the end of the world. The final blow was the prominence of such fiction works as Dante’s DIVINE COMEDY: THE INFERNO, which offer vivid, stylized descriptions of the underworld from the imagination of literary geniuses.

And though vision literature as an industry died with the Middle Ages, it has by no means disappeared from the modern experience. In 1993, Mary K. Baxter published A Divine Review of Hell in which she describes a “40 day” vision of hell complete with odors, haunted tunnels, and torture chambers “like a horror movie.” Other accounts of infernal NEAR-DEATH EXPERIENCES, also penned over the last few years, have likewise described a treacherous abyss where sinners will suffer for all eternity, even in this enlightened age. Like their medieval precursors, these contemporary tales warn readers that the day of reckoning is indeed on its way.

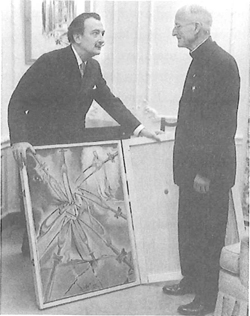

VISION OF HELL, THE Twentieth-century surrealist Salvador Dalí created a frightening depiction of the underworld with his 1962 The Vision of Hell, based on a supernatural experience of LUCIA DOS SANTOS in 1917. His painting shows a condemned soul being twisted and tortured with sharp forks in a desertlike inferno. In the background, fire, smoke, and DEMONS pour forth from a jagged chasm. Above, the VIRGIN MARY, mother of Jesus Christ, offers hope to humankind by encouraging them to turn to her son for salvation, thus escaping the bitter wages of sin.

The work was commissioned by an anonymous donor who feared that “Hell has ceased to be a reality to millions” and that this ignorance would lead to the eternal damnation of countless souls. Dalí presented the painting to Monsignor Harold V. Colgan, founder of the Blue Army of Our Lady of Fátima (an organization dedicated to spreading the message of sanctity, repentance, and reparation), in hopes that it would serve as a reminder of the “penalty of sin.” The Vision of Hell was hung at the Blue Army’s headquarters in New Jersey, where it remained in relative obscurity for more than three decades. The modern masterpiece was recently “rediscovered” by the organization’s members and is now being exhibited throughout the world.

Salvador Dalí presents his interpretation of the Vision of Hell to Msgr. Harold V. Colgan of the Blue Army of Our Lady of Fátima. PHOTO COURTESY OF THE BLUE ARMY OF OUR LADY OF FÁTIMA, USA, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

VIZARSH Vizarsh is the fearsome DEMON OF ZOROASTRIANISM who seizes evildoers attempting to cross Cinvato paratu (CHINVAT BRIDGE). These damned souls are “followers of the lie” who have betrayed the truth. As they try to navigate the narrow passage that leads to paradise, the weight of their sins causes them to fall into hell, where they are attacked by the vicious Vizarsh.