CAESARIUS OF HEISTERBACH The sermons and exempla of Caesarius of Heisterbach (c. 1230) are filled with vivid, terrifying images of SATAN and the accursed abyss. The thirteenth-century Christian cleric also heavily preached about the LAST JUDGMENT, routinely filling his parishioners’ minds with images of grisly DEMONS, bloody tortures, and everlasting fire that await evildoers in the world to come. He warned them of the eventual end of the world, a time at which Christ will return to judge the souls of all people, living and dead, and cast the irrevocable sinners into the depths of hell. His doctrines were repeated at pulpits throughout every Christian nation and became the basis for countless HELLFIRE SERMONS during the following century.

Caesarius encouraged devotion to the VIRGIN MARY for protection against damnation. He believed that Christ’s mother had the power not only to save souls from being condemned but also to visit hell to retrieve sinners from the underworld. His writings include the example of a corrupt monk who had died, been damned, but was restored to life through Mary’s intercession. The man repented, led a devout life, and eventually became a saint. This case history was spread throughout Chrisendom and was cited to convince the wicked to mend their ways. Caesarius’s teachings also became instrumental in securing the Virgin’s reputation as intercessor for human souls.

CAIN Lord Byron displays his self-proclaimed contempt for traditional morals in his poem Cain. The work is sympathetic to both LUCIFER and to Adam and Eve’s wicked son Cain, the biblical figure who murders his brother Abel out of jealousy. Byron’s Cain turns the killer into a hero for asserting his independence and God into a vain despot who demands an unreasonable amount of tribute and adoration to feed his massive ego.

In Cain, Byron (who had recently learned of the first discoveries of dinosaur fossils) depicts the extinct reptiles as superhuman creatures who once inhabited the earth. After falling from grace, they are damned to a hell located somewhere in outer space. Young Cain is transported there by his host, Lucifer, an energetic fiend who has been unfairly banished from paradise. Byron describes these ancient beasts as sadly beautiful, inhabiting the “gloomy realms” of the dark abyss. He feels sorrow for the “immense serpent” (an Enlightenment LEVIATHAN) and the other monsters languishing in their exile.

Cain celebrates the rebellious creatures and their fiery bravado. Not surprisingly, Byron’s poem was immediately condemned as blasphemous for elevating Lucifer to the level of supernatural hero while decrying the Creator as a petty tyrant. Byron relished this condemnation—it was exactly the reaction he had wanted. He believed that this rebuke was proof that his intellect frightened and intimidated “superstitious” believers. The poet gave similar favorable treatment to the legendary rogue DON JUAN, an unscrupulous scoundrel for whom Byron has nothing but praise.

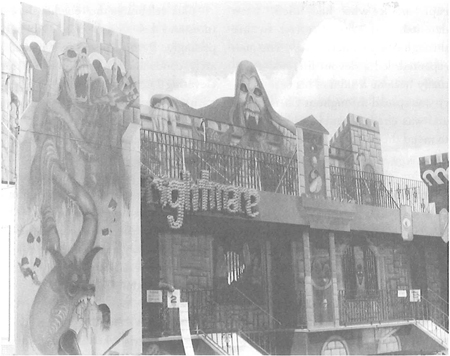

CARNIVAL ATTRACTIONS Amid the Ferris wheels, cotton candy stands, and pitch-till-you-win games at many roadside carnivals, revelers often find scary attractions that promise to thrill and chill brave patrons. These “haunted houses” are also mainstays at many major amusement parks, from Coney Island to Disneyland. And every Halloween brings scores of part-time underworld concessions to neighborhoods across the country. Spooky enticements with names such as The Bottomless Pit, Dante’s Inferno, Hell Hole, Chamber of Horrors, Village of the Damned, and The Devil’s Den often take their themes from the depths—and horrors—of hell.

These forbidding attractions draw ideas for frightening images from myth, literature, and art. Most exteriors include pictures of menacing a DEVIL, GHOULS, skeletons, corpses, and witches languishing in hellfire. Inside, patrons find both live figures, usually dressed as DEMONS or familiar fiends such as Dracula and Frankenstein, and gory displays of severed body parts, open graves, and bloody implements of torture. Sound effects of howling devils and screaming souls underscore the infernal atmosphere.

Carnival haunted houses feature such icons of hell as Satan, demons, and Leviathan.

Another popular feature is the oversized statue of a threatening demon. SATAN and LUCIFER are most common, usually shown as red fiends with horns and claws, wielding razor-sharp pitchforks. Mythic underworld beasts such as the guard dog CERBERUS and ferryman CHARON are also perennial favorites. Monsters of modern American pop culture (child killer Freddy Kruger of NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET, for example) have begun showing up in more and more spook houses.

The popularity and prevalence of these attractions reinforce the fact that people are fascinated with hell and are interested in a brief visit. Proprietors have discovered that the suffering of the damned is sensual and darkly stimulating. The sinister appeal of such concessions has been captured in horror stories and movies as well, including the suspense novel HIDEAWAY and motion picture DANTE’S INFERNO.

CARNIVAL OF SOULS The 1962 film Carnival of Souls depicts a grim afterlife where the dead continue on in a sort of faded existence, similar to the SHADES of ancient Greek myth. Originally a low-budget independent, the movie has attracted quite a cult following. Filmed almost entirely in Kansas (at a cost of less than $100,000), Carnival of Souls offers an unsettling look at the supernatural realm through the eyes of Mary Henry (played by Candace Hilligoss), a young organist whose recent brush with death leaves her haunted by a recurring specter.

Carnival of Souls opens with the scene of a two cars drag racing, speeding recklessly down a rural lane. When the race continues onto a narrow bridge, the vehicle containing Hilligoss and her friends goes out of control and plunges into the river below. She emerges from the water seemingly unscathed but soon begins having frightening visions of a pale, grinning stranger who is stalking her. Hilligoss quickly arranges to leave town, dispassionately telling acquaintances, “I’m never coming back.”

The organist drives across the country to take a job as soloist at a new church. Her hallucinations continue as she travels, and Hilligoss quickly realizes that the smirking man is following her. When she arrives to assume her new position, the pastor of the church finds her to be cold and “soulless.” Her maniacal organ playing horrifies him, sounding more like a diabolical dirge than a joyous hymn. The minister gently suggests that she “accept help” in the form of spiritual guidance to remedy her “profane” behavior. He then asks her to resign. She quietly agrees, not knowing what inspired her eerie outburst.

The bizarre events of her life continue after she flees the church. As a new boyfriend bends to kiss her, she sees him reflected in the mirror as the sinister GHOUL who has been menacing her since the auto accident in her hometown. Hilligoss tries to buy a bus ticket out of town, but no one at the station can see or hear her. Scrambling onto one of the waiting buses, she discovers that the passengers are all pale corpses, led by the familiar phantom. She runs screaming from the scene, unable to comprehend—or stop—the horrible visions.

Confused and terrified, Hilligoss heads for an abandoned lakeside pavilion on the edge of town that seems somehow to be connected to the strange events. Inside she discovers a ghostly gathering of vacant-eyed zombies dancing lethargically to an unearthly tune. None of them speak; they swirl endlessly in a slow, morbid waltz. Before she can escape this macabre prom, Hilligoss sees herself, also a vacuous ghost, dancing in the arms of the ghoul who has been pursuing her. Horrified, she turns and runs out onto the lakeshore. The dancers run after her, overtaking her on the wet sand at the water’s edge.

Carnival of Souls concludes with a scene at the riverside back in Hilligoss’s hometown, where the car accident initially occurred. The smashed vehicle is pulled from the water with her drowned body still trapped in the wreckage. Hilligoss’s misadventures and ultimate arrival at the haunted pavilion have been part of her bleak afterlife, a somber realm of gloomy existence. Her journey has not been to a new town and a second chance at life, but to a bitter, monotonous eternity. Hilligoss has at last embraced her destiny.

CAVE OF CRUACHAN The Cave of Cruachan in Connaught, Ireland, has been called the “Gateway to Hell” by early Christian folklorists. Its reputation derives from ancient pagan stories linking the cavern with the underworld. The old legends claim that Cruachan is actually a portal through which dead armies of zombies come to attack the living. Christians updated the tales, asserting that the harsh geologic formation is where human souls enter the abyss of the damned.

CERBERUS Cerberus is the Greek mythological guardian of the underworld. He is a ferocious three-headed dog with serpents’ tails and a body entwined with vipers. Cerberus sits at the gates of HADES, gnawing on human bones. His duty is to prevent the dead from escaping and the living from invading the underworld. Cerberus’s fierce howling and putrid stench are so frightening that few even dare approach the passageway.

Only two mortals, ORPHEUS and HERCULES, have ever bested Cerberus. Orpheus charmed him to sleep with his enchanted music; Hercules wrestled him into submission as part of one of his legendary labors.

Cerberus appears in scores of artwork, in Dante’s DIVINE COMEDY: THE INFERNO, and in the motion picture HIGHWAY TO HELL.

CERNUNNOUS Cernunnous (the Horned One) is the ancient Celtic god of the underworld and ruler of the dead. Images of the dark sorcerer etched into cave walls in France date back to 9000 B.C. He is portrayed as a horned deity surrounded by fearsome animals. Also associated with hunting and fertility, Cernunnous became identified with the Antichrist when Christianity spread to the Celtic regions. After the conversion of Ireland, Cernunnous was increasingly linked with a dark and foul underworld, the dwelling place of evil spirits and souls of the damned.

CHARON Charon is the escort who ferries the dead to HADES, the underworld of ancient Greek myth. Souls must pay him for this service; otherwise they will be left to wander aimlessly the banks of the river STYX throughout eternity.

The mythic Charon appears in hundreds of plays, poems, paintings, films, and other creative works. Homages to the ferryman can be seen in the movie HIGHWAY TO HELL, in MUSIC VIDEOS, and on centuries-old MEMORIALS to the dead.

CHARON ON THE RIVER STYX Joachim Patinir’s sixteenth-century painting CHARON on the River STYX exemplifies the lasting influence of ancient Greek myths on the art world. Created more than two millennia after the demise of Helenic civilization, Patinir’s composition employs underworld images and icons that have endured through the centuries. The work is a brilliant blaze of blues and greens illuminating paradise, a stark contrast to the dark and sinister colors of the land of the damned.

In Charon on the River Styx, Patinir offers a naked, gaunt Charon perched in a tiny rowboat ferrying souls across the river Styx to a grim fortress of torture. The underworld looms in the background, a burning city choked with black smoke. The gates of HADES await on the opposite bank, guarded by the three-headed beast CERBERUS. Broken bodies dangle limply over the walls, still being tormented by DEMONS. Farther on, souls are thrown into a raging fire by gleeful fiends. The faces of the damned are upturned in agony, longing for relief that will never come.

“CHILDE ROLAND TO THE DARK TOWER CAME” Poet Robert Browning told his contemporaries that his existential poem “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came” “came upon me as a kind of dream.” He denied that there was any specific allegorical meaning; however, the work includes a chilling passage that invokes images of a treacherous CHRISTIAN HELL. One line declares that the “LAST JUDGMENT’s fire must curse this place,” a clear allusion to the spiritual grotesqueness of the underworld. Browning also makes several explicit references to the DEVIL and to APOLLYON, the angel of the abyss.

Childe (a title indicating a young gentleman who is awaiting knighthood) Roland is a feisty warrior in search of adventures and glory who embarks upon a grim quest to storm the mysterious Dark Tower. During this bleak adventure, he comes to a river of writhing bodies groaning in utter agony. Its “black eddy” could have “been a path for the fiend’s glowing hoof.” The ravaged spirits in this mire are held there by some ominous power, for there is “no footprint leading to that horrid mews, none out of it.”

As he crosses the river, the speaker is horrified by the ghastly carnage beneath his feet:

Which, while I forded, good saints, how I feared

To set my foot upon a dead man’s cheek,

Each step, or feel the spear I thrust to seek

For hollows, tangled in his hair or beard!

It may have been a water-rat I speared,

But, ugh! it sounded like a baby’s shriek.

This repugnant stream extends far into the distance, “a furlong on,” to a gruesome engine that perpetually would “reel men’s bodies out like silk.” He is chilled not only by this aberration but also by the unseen force that keeps these damned souls from escaping. The narrator gratefully reaches the opposite bank but cannot escape the haunting specter of this dark, hideous river. Yet Roland’s worst vision is yet to come.

When he reaches the courtyard of the Dark Tower, Roland is horrified to see among the castle’s occupants the faces of fallen friends who have died during battles. They look out at their former companion with vacant, haunted eyes. Roland laments “in a sheet of flame I saw them” before pity forces him to turn away. Rather than invigorating his spirit and whetting his taste for such feats, the trip to the Dark Tower has left him broken and desolate, questioning the very nature of his own purpose in the world.

CHILDREN’S LITERATURE A number of children’s stories involve the land of the damned, either directly or allegorically. Some are cautionary tales designed to help young ones follow the path of righteousness; others are simply satirical whimsies that downplay the horror of the underworld. The oldest date back centuries; the most recent have been around for less than a decade, demonstrating the timeless appeal of infernal yarns.

Throughout the ages, overanxious zealots, eager to begin saving tender young souls, composed stories designed specifically to frighten children into behaving in an acceptable manner. Children around the world have listened breathlessly to tales of naughty children who defy their elders or thwart societal rules, then end up in a ghastly underworld where they must pay for their offenses. Such stories are followed by a not so subtle warning: Do as you’re told and this won’t happen to you. One of the most extreme examples is “Sight of Hell,” penned by Rev. Joseph Furniss in the late 1800s. His work details the horrors of the inferno in simple-to-understand terms, vividly describing a young child writhing in a “red hot oven.” Furniss admonishes young followers against such juvenile offenses as disobeying parents, telling tales, and missing Sunday services.

An 1864 illustration from The History of Our Lord: Vol I shows wicked children suffering the fires of hell. ART TODAY

Secular stories, too, could be downright horrifying for youngsters. Among the most disturbing examples of hellish literature for children is Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Girl Who Trod on a Loaf.” The tale describes the damnation of Inger, an “arrogant” child who fails to appreciate her parents’ love and is ultimately sent to hell. Inger seals her doom when she throws a cake of bread that was to be a gift for her mother into a mud puddle to use as a stepping stone. More concerned about soiling her shoes than about her impoverished parents, Inger immediately sinks into the “black bubbling pool” full of “noisome toads” and “slimy snakes.” In this murky underworld, Inger experiences “icy cold,” “terrible hunger,” and other severe pains. Inger’s mother weeps for her lost child, but her tears only “burn and make the torment fifty times worse.” Eventually, Inger is released from hell through her sainted mother’s prayers, but only to exist as a songbird.

Few fables are as harsh as this; most use gentle metaphor to warn children about the consequences of sin. In Pinocchio, for example, naughty boys who disobey their parents are transformed into donkeys. This reflects the common belief that damned souls become beastlike in the afterlife. Likewise, the burning of the witch in “Hansel and Gretel” symbolizes the fires that await evildoers in the underworld. And the story of the “Billy Goats Gruff” contains several examples of infernal IMAGERY. The innocent animals must pass over a dangerous bridge while a wicked troll waits below to devour them. Only by knowing the correct words to outsmart the monster can the little goats escape. The hellish images of a perilous bridge, an evil fiend, and magic spells are components of a number of ancient myths and religious doctrines regarding the afterlife.

Hell continues to be used in children’s tales, although contemporary stories are usually more humorous than allegorical. The DEVIL and Mother Crump, written in 1987 by Valerie Scho Carey, tells of a cantankerous woman who outsmarts the DEMONS of the underworld by proving herself more despicable than the fiends. For when Mother Crump dies and LUCIFER calls her to hell, she so enrages the devils sent to claim her that they finally give up trying. Eventually, Mother Crump decides that she is old, exhausted, and ready for death. But heaven won’t have her, and the angels send her down to hell. Lucifer, remembering the beating he took from her years ago, refuses to let her in. Instead he gives her a coal and tells her to create a hell of her own. Mother Crump ultimately maneuvers her way into paradise, providing a happy ending for young readers.

Child-oriented tales of the underworld—both terrifying and trivial—can also be found in ANIMATED CARTOONS, COMIC BOOKS, and COMPUTER GAMES. There are also numerous feature films designed for children that include depictions of the great below, such as ALL DOGS GO TO HEAVEN, THE DEVIL AND MAX DEVLIN, and Disney’s 1997 animated version of HERCULES.

CHIMAERA Chimaera is a mythical underworld beast that appears in a variety of legends and works of Western literature. He has a lion’s head, goat’s body, and serpent’s tail. Chimaera also figures in ETRUSCAN mythology as a fierce underworld DEMON.

In PARADISE LOST, John Milton describes Chimaera as a fire-breathing monster who inhabits hell. He is a guardian of the gates of HADES according to the poets Homer and Virgil. In the AENEID, Virgil depicts Chimaera as “armed with flames” and horrible to behold. And the beast is referred to as the father of the DEVIL in the Faerie Queene, a sixteenth-century tale of goblins, FAIRIES, and other figures of the “otherworld.”

CHINVAT BRIDGE According to ancient Persian myth, when a person dies, the soul remains by the body for three days. On the fourth, it travels to Chinvat Bridge (the Bridge of the Separator, also called Al-Sirat), accompanied by gods of protection. The bridge is “finer than a hair and sharper than a sword” and spans a deep chasm teeming with monsters. On the other side of the bridge is the gateway to paradise.

DEMONS guard the foot of the bridge and argue with the gods over the soul’s fate. The actions of the dead person, both good and bad, are weighed, and the soul is either allowed to cross or denied access to the bridge. Spirits whose evil outweighs their good fall into the demon-infested pit to face eternal torment. In this abyss of the damned, each soul is tortured by a GHOUL that represents its sins in life. Once fallen into the gulf, no soul can escape the horrors of hell through its own power.

Zoroaster, a sixth-century B.C. religious leader, had warned his followers of this obstacle to heaven but promised to lead his flock safely across. The ancient manuscript Gathas (Songs of Zoroaster) explains that the Bridge of the Separator “becomes narrow for the wicked,” whereas the holy can easily pass unharmed. (In Gathas, the fair god Rashnu is named as the judge who helps determine who is worthy of salvation and who must be damned.) All infidels (nonbelievers) fall into hell, which the prophet says has been created especially for the “followers of the lie.”

The legends are sketchy but assert that Chinvat Bridge is located somewhere in the far north. It is a place of filth where the damned endure physical tortures and spiritual agony. Souls who are unsuccessful in crossing Chinvat Bridge suffer these torments until AHRIMAN, the evil god of ZOROASTRIANISM, is destroyed by the good god Orzmahd during the LAST JUDGMENT. At this time, lost spirits are restored to the truth since “the lie” has been eradicated, or they face final ANNIHILATION.

“CHRIST AND SATAN” The Old English poem “Christ and Satan” provides a frightening description of the underworld. It also offers an estimation of the SIZE OF HELL, a mystery that has occupied philosophers and scholars since the inception of underworld mythology.

According to the work, hell is a “horrible cavern underground” that is impermeably dark, where fires continuously burn but give off no light. Those in hell, creatures who once sang hymns of joy, now wail and shriek in everlasting mourning, bound in chains of fire. Their ultimate misery is their refusal to accept their fate. They are damned to spend eternity raging against God and seething at their predicament.

The fallen angels in hell blame SATAN for causing their damnation. They accuse him of lying and misleading them by claiming he could replace God and reward them with places of honor in paradise. Remembering the beauty of heaven causes them unbearable agony since that glory is now forever outside their grasp. They lament “alas that I am deprived of eternal joy” and left with unending sorrow.

“Christ and Satan” also includes an account of the HARROWING OF HELL, when Jesus raids the underworld and frees the souls of the patriarchs. As he appears at hell’s gate, a song of rejoicing erupts from the faithful. Satan, powerless to stop him, must stand idly by as Jesus delivers the just to heaven. Before leaving, Jesus warns Satan that this is not his final defeat, for a larger battle is waiting at the time of the LAST JUDGMENT. This will occur at the end of the world, when Satan will be vanquished for eternity.

CHRISTIAN HELL Christian hell is a place of final justice for the wicked who have offended God and have died without seeking forgiveness. The Bible describes the realm as “everlasting fire prepared for the DEVIL and his angels” where souls of the damned suffer according to their sins. It is called a “lake of fire” and a “bottomless pit.” SATAN, a former angel who rebelled against God and started a war in heaven, is hell’s overlord.

There is no generally accepted information regarding the location or SIZE OF HELL, nor is there a consensus about who has been damned. In fact, most Christian leaders teach that there is no evidence that any souls have been condemned to this eternal abyss. (Some scholars believe that the Bible implies that Judas is in hell. Jesus is quoted as saying, “It would be better for him [Judas] if he had never been born.” They theorize that the only fate worse than nonexistence is damnation to hell.)

Theologians and philosophers through the ages have attempted to offer details about the nature of the underworld; however, little doctrine has been universally accepted. As we head into the twenty-first century, the specifics of Christian hell remain unresolved. Many hold the view that the underworld is a place of sensory torture and agony; others believe that it is merely a state of mental anguish. Still another group believes that damnation to hell is a temporary punishment before ANNIHILATION. These various interpretations of the underworld are illuminated in numerous literary works by Christian authors, including Dante’s DIVINE COMEDY: THE INFERNO, Milton’s PARADISE LOST, and a host of MYSTERY PLAYS and MORALITY PLAYS. Visions of the land of the damned are also depicted in paintings, sculptures, and mosaics found in Christian CHURCH ART AND ARCHITECTURE.

ST. AUGUSTINE, a fourth-century doctor of the church, wrote several academic texts regarding hell. In CITY OF GOD, he asserts that in the underworld, the damned suffer both physically and spiritually and that this torment continues for all eternity. He cites the Bible and traditional beliefs as the basis for his deductions, such as the passage in the Gospel of St. Matthew that those who ignored Christ’s words “shall go away into everlasting punishment.” Augustine’s theories were sanctioned by Christian authorities at the Synod of Constantinople in 543 and heavily influenced the teachings of both Martin Luther and John Calvin. And his conclusions about the underworld are still taught in Catholic institutions.

Yet many Christians believe that the pains of hell are metaphorical. The fires of the underworld, for example, are not actual flames but the burning pangs of a guilty conscience. The “everlasting torment” is the unending separation from God. Evangelist Billy Graham professed this belief in his Sermons from Madison Square Garden in 1969. He stated that “the fire Jesus talked about is an eternal search for God that is never quenched,” not a true inferno. This view is shared by many Protestant denominations, which find the notion of a place of physical torment to be somewhat outdated and incompatible with the notion of a merciful God.

Modern concepts of horrors in the afterlife have also been weakened by the atrocities witnessed by recent generations. It is difficult to imagine greater terrors than the Nazi concentration camps, nuclear devastation, and the wholesale slaughter of political dissidents in China, Cambodia, and Eastern Europe. And the advances of technology have led many to believe that there is no place for traditional hell in the mind of today’s educated and enlightened thinker. For this reason, some have embraced annihilation theory, which maintains that in the afterlife evil souls will be eradicated from existence.

Critics of annihilation theory claim that belief in an underworld for unrepentant sinners, whether actual or metaphorical, remains essential to the importance of Jesus Christ’s redemption of humanity. Without a hell, his sacrifice and death would not have been necessary. Many further claim that existence of hell also serves as proof of free will. God does not force anyone to love him nor to spend eternity with him in heaven if that individual would rather choose evil, selfishness, and ultimately damnation.

Today, most denominations emphasize God’s mercy and encourage their faithful to strive for heaven rather than try to cheat hell. They also stress that damnation is a choice made by those who reject the Almighty and not a punishment imposed on evildoers by an angry or vengeful deity. So while debate continues over the specifics of the unpleasant afterlife, most Christians retain that hell is real and that everyone is vulnerable.

CHRISTIAN TOPOGRAPHY Sixth-century Egyptian monk Cosmas Indicopleustes offers an unusual description of hell in his treatise Christian Topography. According to the manuscript, Earth is completely flat, protected by the “dome of Heaven” above. Damned souls will “sleep” below the ground until the LAST JUDGMENT, when the material world will be transformed into hell. After this occurs, the earth will become harsh and barren, a perpetual desert devoid of any plant or animal life. Evil spirits will be forced to spend eternity in this wasteland, while the saved are restored to heaven to savor the abundant delights of paradise.

Indicopleustes’ theories were rejected by both scientists and religious scholars of the time. However, the peasantry excitedly embraced his model of the supernatural universe. For decades, the concept of a ravaged earth serving as hell was the topic of countless sermons, lectures, and lively debate.

CHRISTINA, SAINT St. Christina (1150–1224) was born in Brusthem and became an orphan at age fifteen. Seven years after the death of her parents, Christina had a disturbing vision of hell following a near-fatal brain seizure. The young woman fell into a comalike state, and doctors, unable to revive her, pronounced Christina dead. She was laid in her coffin and taken to the church for a Requiem Mass. During the funeral, however, she sprang up from her coffin and levitated to the church rafters. The priest told her to come down, but she refused, claiming she was sickened by the stench of people’s sins.

Christina then recounted her supernatural travels, telling the stunned cleric that she had in fact died and been taken on a tour of heaven, purgatory, and hell. In the underworld, she saw sights so horrible she could not bring herself to put them into words. God invited her to remain with him in heaven but also offered her opportunity to return to life to help others avoid hell and to aid the suffering of those in purgatory through her sacrifice and intercession. Sickened by the severity of the torments she had witnessed among the damned, Christina decided to rejoin the living and help others attain heaven.

Christina lived out her life in prayer and penance, continually spreading the warning about the consequences of sin. She died in 1224 at the Convent of St. Catherine at Saint-Trond and was eventually canonized as saint of the Roman Catholic church.

CHRONICLES OF HELL, THE Belgian dramatist Michel de Ghelderode wrote more than four dozen plays during his lifetime, most of which contain supernatural elements. His satirical treatment of the FAUST legend, called The Death of Doctor Faust, was well received by critics and audiences alike. However, his 1929 composition, The Chronicles of Hell, was by far his most adventurous and controversial work. When it was first produced in Paris in 1949, the play was condemned as sacrilegious and its author labeled a blasphemer. Despite the criticism, The Chronicles of Hell—a rich blend of religious satire, infernal IMAGERY, and ludicrous stereotypes—remains popular among modern audiences.

The Chronicles of Hell’s setting is a Gothic cathedral in “bygone Flanders.” Ghelderode describes the set as a decaying antechamber decorated with witches’ masks, statues of pagan DEMONS, and brutal torture devices. In the foreground, a great table laden with succulent food and crystal goblets stands ready for a funeral banquet. Outside, a raging storm brings explosions of lightning and thunder, underscoring the eerie atmosphere of the vile place.

As the one-act play opens, six clergymen gather to mark the death of Jan Eremo, a powerful bishop. Rather than offer reverent prayers, the clerics insult both the departed man and one another, mocking their physical impediments and erupting into petty squabbles over the funeral feast. They trade opinions about the deceased—whom they loathed—and speculate on his ties with the DEVIL. When one priest suggests that the deceased bishop is bound for hell, a colleague coldly replies “he has been there” before. A third retorts, “Yes, to buy a place there for you, in a noxious dungeon where you will crush slugs!”

As the accursed men trade insights and insults, the storm is growing stronger and a mob of angry villagers is assembling outside the gates of the cathedral. They are mourning their beloved bishop, whom they credit with saving their town from the horrors of the plague and from starvation. His fellow clerics believe he accomplished this feat through demonic intervention, and their hatred of Jan makes them enemies of the people. The priests decry their former bishop as the Antichrist and are delighted that he is finally dead. Each flash of lightning illuminates the faces of the pagan idols that seem to be grinning in approval of the blasphemous scene.

The squabbling continues. Suddenly, at the height of the tempest, the mortuary chapel doors burst open, and Jan’s towering figure lurches toward the bickering men. One demands of the corpse, “Have you seen Hell?!?” but the reanimated bishop is unable to reply. He had been given Communion just before dying, and the holy wafer chokes him, burning in his throat. Hell will not accept him while the Eucharist rests within, and heaven has long since renounced the diabolical reverend. Caught between life and death, the bishop stumbles blindly through the dark chamber of evil relics. Finally, his jealous successor runs forth and rips the communion bread from the bishop’s throat, sending Jan back to his damnation.

In the aftermath of the commotion, the assembled clerics continue ridiculing one another. Several have “filled their cassocks with dung” in fits of fright at seeing the ambulatory corpse. They are chided by the others, who light up incense to mask the smell. Without warning, the mob becomes riotous and smashes into the dismal cathedral, demanding the body of the bishop. As the scene degenerates into total chaos, the priests, who have been exposed as hypocrites and nihilists, realize that they, too, are damned. The words of one minister resonate throughout the cathedral: “We are all in the abyss.”

Ghelderode’s The Chronicles of Hell explores themes common to infernal literature: deals with the devil, hypocrisy of the clergy, the seductive lure of diabolical powers. His play generated controversy mainly because it depicts the clergymen as villains rather than heroes. Such works as AMBROSIO THE MONK, “VATHEK,” and EPISTOLA LUCIFERI are likewise critical of “men of the cloth” and suggest that they may in fact be among the fiercest allies of hell.

CHTHONIC The word chthonic means “relating to the gods of the underworld.” It is from the Greek khthonios, “of the earth.” Chthonic deities include rulers of the netherworld such as OSIRIS, HADES, HEL, YAMA, EMMA-O, and Pluto. Chthonic myth and literature include the legends of ORPHEUS, THESEUS, and HERCULES in the land of the dead, Virgil’s AENEID, and Homer’s ODYSSEY.

CHURCH ART AND ARCHITECTURE Images of the underworld decorate churches, temples, and places of worship throughout the world. During the days of widespread illiteracy, elaborate depictions of the damned helped illustrate the horrors of hell to congregations unable to read the sacred texts. Paintings, carvings, and statues of grisly DEMONS and damned mortals were among the most popular ornaments at religious sites.

One of the earliest examples of infernal art is Polygnotus’s painting of Odysseus’s visit to the kingdom of HADES inspired by Homer’s epic poem the ODYSSEY. The picture, which dates back to the fifth century B.C., was part of a shrine to the Greek god Apollo. Unfortunately, the drawing—which showed a huge blue-black DEMON savagely eating the flesh of the damned—has been destroyed. Descriptions of the work, however, are contained in the writings of Greek scribe Pausanias.

In the Far East, graphic depictions of the gruesome horrors of BUDDHIST HELL became very popular in the Kamakura period during the twelfth century. Portraits of sinners languishing in agony and suffering a variety of ghastly tortures were etched onto hand scrolls along with text explaining the designs. These are examples of NISE-E, “likeness paintings,” which took great inspiration from tales of the nether regions.

A centuries-old painting found in a Tibetan Buddhist temple includes similar images of the underworld. In this work, souls are shown writhing in the flames of hell, being beaten with clubs, gnawed upon by beasts, and jabbed with spears of fire. Wide-eyed demons delight in inflicting these and other punishments on the spirits of those sent to the underworld. Another artwork shows EMMA-O, ruler of the dead, as a green monster smashing a condemned spirit with a blood-stained mallet.

But by far the most graphic and extensive scenes of the land of the damned exist in Christian churches. As Christianity spread across the globe, artists of all backgrounds and cultures began illustrating the fiery underworld. Their works remain in chapels and cathedrals throughout the world, offering valuable insight into evolving beliefs about the horrors of CHRISTIAN HELL (as well as providing a history of the world’s greatest artists).

The St. Lazare Cathedral in Autun, France, features a carving of angels weighing human souls while demons try to tip the scales in favor of damnation. This complex TYMPANUM RELIEF shows the LAST JUDGMENT when the saved are admitted to paradise and the damned cast into hell. The relief depicts horned devils taunting spirits and dragging sinners into the underworld while other condemned are being eaten by monstrous creatures. The Tympanum Relief was carved in the early twelfth century as a reminder to parishioners to heed the laws of the church.

A fourteenth-century frieze at Orvieto Cathedral in Italy shows condemned souls, bound together by thick ropes, being hauled off to hell by loathsome demons. Grinning devils, farther down in the bowels of the abyss, rapaciously devour the damned. One particular detail shows a drooling demon biting off the arm of a screeching man. The fiend’s fellow GHOULS laugh approvingly at the grisly spectacle.

The Temptation of St. Anthony by Max Ernst, a rich oil done in royal blues and ruby reds, shows hell as a vibrant world of sensuality. Its demons are odd mutant animals: furry trunks with bird beaks and sharp claws; reptile cats with snake-weasel tongues. The background shows voluptuous nudes carved into the cliff walls of the underworld. Hell’s inhabitants are beasts with human faces, their eyes dark sockets being clawed by razortaloned devils who bite and flail at each other.

At the Monastery of St. Catherine at Sinai, a painting by St. John of Climax depicts the Ladder of Judgment. Souls try to ascend, but the evil are shot by demons’ arrows or impaled on pitchforks and then pulled into hell. A sixteenth-century Russian icon shows a similar scene. Departing souls attempt to climb a ladder into heaven, but the wicked fall into waiting hell below. Winged black demons wait to snatch up the fallen spirits. The work is done in yellows and browns, creating a somber, forbidding mood of despair.

All of these artworks serve as more than mere ornamentation: They bring dire tales of eternal suffering to life. Others, such as those of the Last Judgment and the HARROWING OF HELL, illustrate complex doctrines that might otherwise be difficult for clerics to explain to the peasantry. The tendency to adorn churches with visions of hell, demons, and damnation has faded over the centuries. However, tourists still flock to age-old chapels and cathedrals that feature such ghastly scenes, testifying to the enduring fascination we have with glimpsing a fate we hope never to suffer.

CIRCLE OF THE LUSTFUL WILLIAM BLAKE’s Circle of the Lustful, painted between 1824 and 1827, exquisitely illustrates a passage from Dante’s DIVINE COMEDY: THE INFERNO. The composition shows two condemned souls, damned for their adulterous affair, telling their sad story to the poets Virgil and Dante as the scholars tour the underworld. Virgil is shown listening sympathetically as the once-lovely Francesca recalls the fateful day she and her lover succumbed to temptation. The two had been reading a tale of Sir Lancelot and his amorous adventures when they were overcome with passion. Francesca’s husband, coming upon the couple in the act of adultery, killed them both. Now the pair is condemned to spend eternity swept along by the winds of desire in a never-ending storm. Dante, having heard their story, has fainted from pity and grief.

Circle of the Lustful features Blake’s characteristic distorted anatomical proportions and abstract use of color and movement to illustrate the damned. He uses ink and watercolors to create the whirlwind that eternally propels sinners who, in life, were swept along by their carnal desires. He sends a legion of sensual sinners swirling through the bleak landscape and off into the distance. In contrast to the pale figures of the damned, Blake includes a vibrant portrait of the two lovers as they were in life, still full of lush color. The pair appears above the image of the damned Francesca, as in a vision. This contrast emphasizes the drab, grim realm of Dante’s underworld where those who indulged their carnal desires must languish for eternity.

CITY OF GOD SAINT AUGUSTINE, a sixth-century Christian bishop and doctor of the church, penned City of God to address common contemporary misconceptions about hell and damnation. The text was written specifically in response to the Gnostics, a breakaway sect whose followers believe that life on earth is equivalent to existence in hell. His book refutes the concept of GNOSTIC HELL and dispels its doctrine that all matter is intrinsically evil. Augustine uses Scripture and biblical quotes to support his theories regarding the nature of matter and of the underworld.

City of God asserts that material creations are in fact beautiful and decent, having been formed by God. Augustine reminds readers that in Genesis, the Supreme Being looked directly at the new firmament and “saw that it was good.” It is not until Adam disregards God’s restriction and eats of the forbidden fruit that sin occurs. This free choice is a function of the human intellect and is independent of physical objects. Thus evil results not from matter but through the act of disobedience to God. Material is merely the instrument of humanity’s offense, not its cause.

Damnation to hell, too, is therefore a choice. Humanity has been given the opportunity to attain salvation through the grace of God and the sacrifice of Christ, but we are not forced to accept it. Behavior during one’s lifetime determines whether one is receptive to the grace necessary for redemption. Life on earth is the prelude to eternal punishment or reward rather than the bitter existence preached by the Gnostics. Equating earth with hell, according to Augustine, is not only inaccurate; it grossly underestimates the horrors that await the damned.

The bishop reiterates the distinction between matter and evil by noting that all those who suffer in hell are not material creations. Augustine points out that the fallen angels—purely spiritual beings—also endure agony in the dark underworld. He claims that “evil spirits, even without bodies, will be so connected to the fires” of hell that they, too, will be in unbearable anguish for all time. These fallen angels represent “darkness” and despair while their heavenly counterparts reflect the brilliance and sheer joy of paradise.

Augustine’s City of God describes hell as a lake of FIRE AND BRIMSTONE and asserts that torments of the abyss are physical as well as spiritual. He denies the concept of ANNIHILATION, that souls damned to the great inferno will one day cease to exist. Augustine declares that damnation is eternal and that the nature and severity of the suffering in hell directly correspond to the evil a person has committed during his or her lifetime. City of God also addresses the question of the LAST JUDGMENT, noting that at this time the body and soul will be reunited, resulting in agonies of both the flesh and spirit for the damned. (An illustration from a fifteenth-century edition of City of God shows DEMONS of the underworld jabbing souls with black spears and boiling them in bubbling caldrons.)

Augustine’s conclusions on hell were officially sanctioned by Christian authorities at the Synod of Constantinople in 543. Church leaders decreed that anyone who taught that hell is temporary or that the damned will one day be redeemed would be excommunicated for spreading heresy. (The Synod also rejected the popular notion that anyone calling himself or herself Roman Catholic would be saved from hell simply through affiliation with Christ’s church. Those who live immoral, wicked, or wasted lives were advised that they could not hide behind a label and expect to attain automatic salvation.)

CLICHÉS The lingering cultural importance of hell is evident in the number and variety of common clichés about the underworld. These range from the whimsical to the profane. And most modern infernal phrases have their origins in classic works of literature, ancient myths, or religious teachings.

The expression “going to hell in a handbasket” is actually a derivative of “headed to heaven in a handbasket.” The original phrase referred to one who had special, and perhaps undeserved, protection from unpleasant realities. Its infernal counterpart began as a pun but immediately became a popular way of indicating that an idea or project was doomed.

“All hell broke loose” comes from Milton’s classic PARADISE LOST. The epic tells the tale of Adam and Eve, their sin in the Garden of Eden, and the tragic consequences of their act. Nowadays, the phrase is used to describe a situation that has gotten out of hand or gone terribly awry. “Better to reign in hell than serve in heaven” also originates with Milton.

The military has been the source of a number of infernal clichés. A World War I British army song gives us the term “hell’s bells.” The ditty, crooned by soldiers as they marched into battle, was a satirical tune mocking the enemy. One line claims, “The bells of hell go ting-a-ling-a-ling for you but not for me!”

General Sherman is credited with authoring the quip “War is hell.” What he actually said to his troops was, “There is many a boy here today who looks on war as all glory. But boys, it is all hell.” The popular line “I’ve done my time in hell” likewise derives from a military writ. The tombstone of a Marine killed in battle asks that St. Peter allow the soldier to enter heaven immediately, since he has already served his term in the underworld.

Love, like war, also spawned its share of hellish clichés, such as “hell has no fury like a woman scorned.” This astute observation comes from a love poem by William Congreve. In his 1693 play The Old Bachelor, the poet notes that there is no greater horror, in this world or in the realm of the damned, than a lady who has been wronged. Commenting on charitable love between brethren, St. Frances de Sales noted in a letter that “hell is full of good intentions.” The paved road was later added to complete the popular expression.

COMIC BOOKS Hell has served as a backdrop for comic book action for almost a century. Current titles include Hellbound, Dances with Demons, Hell Blazer, Specter, Dark Dominion, Harrowers—Raiders of the Abyss, and Hell Storm. The underworld is also the setting of innumerable stories contained in other pulps, such as TWILIGHT ZONE MAGAZINE, Ellery Queen Mysteries, and Alfred Hitchcock Magazine. And in the computer age, the inferno is available on-line via electronic books and “virtual toys.” In the comic world, hell is both glamorized as a fascinating realm of mystery and depicted as a grisly prison for the wicked.

The history of using hell in such publications goes as far back as the early 1920s, when Weird Tales was first published. This innovative pulp featured the talents of such up-and-coming writers as Ray Bradbury, August Derleth, and Robert Bloch. Stories routinely involved the damned and portrayed hell as everything from a fiery pit to a plush bordello. These early tales whetted the reader’s appetite for unconventional illustrations of the underworld and served as the forerunners of today’s comic series. Imitators soon followed, and horror comics quickly took their place among the most popular titles in America.

Infernal comic books reached their zenith in the 1950s, when Entertaining Comics (E.C.) and a number of smaller presses couldn’t keep Fate, Haunt of Fear, Tales from the Crypt, and a host of other spooky pulps on the shelves. By 1953, horror comics accounted for 25 percent of total sales, split almost evenly between adult and child purchasers. The craze was so popular that it prompted the government—still in the throes of McCarthyism—to produce a film warning parents about the dangers of these publications. According to narrator Ron Mann, these evil texts were part of a Communist plot to corrupt the youth of America by turning bright, patriotic children into “masses of jangled nerves” incapable of functioning in school or society. Mann showed an assortment of titles that parents should “look out for” and even interviewed a darling little eleven-year-old who tearfully told viewers how he “threw up” after reading one of these horrible comics.

In April of 1954, the United States Senate called for subcommittee hearings on the problem. Dr. Frederic Wertham, a German-born psychiatrist, testified that these demonic tales were corrupting the American psyche. Restrictions were imposed on comics as a result of these hearings, and many “offensive” words, including horror and terror, were censored from the titles. Authorities also disallowed inclusion of any “undead” creatures in the stories, including VAMPIRES and damned souls languishing in hell.

The strategy backfired: Sales soared. Critics realized that they were giving infernal comics an incredible amount of free publicity, arousing the curiosity of every prepubescent child in the country. To further aggravate the situation, the restrictions on comic books spawned a whole new cult fascination: monster television shows. Fans of the supernatural who could no longer satisfy their cravings through printed comics quickly tuned in to the new wave of programs hosted by underworld GHOULS.

Since the Establishment couldn’t eradicate the desire for this type of entertainment, it decided to join them instead. The guardians of public morals adapted the horror comic format for their own purposes. Over the next few years, religious publishers put out thousands of pulps featuring grisly pictures of hell that depicted all manner of unpleasant tortures awaiting the damned. At the end of each tale was an invitation to read the Bible, repent, and return to Christian values to avoid such a fate. By the 1970s, these pulps were also incorporating into their stories warnings about the connection between drug use and damnation. One of the most successful was Hal Linsey’s There’s A New World Coming, a 1973 comic showing teens witnessing the torments of the damned as outlined in the New Testament book REVELATION.

Today, most underworld comic books feature “HADES raiders,” heroes who try to save souls from hell while placing themselves in grave peril. Others, such as Hell Hound, are tales of guardians of the gate: champions who keep loathsome ghouls from escaping the underworld or who hunt down runaway fiends who are terrorizing the living. Dances with Demons, Vault of Horror, and Lord of the Pit all highlight the everyday adventures of life in hell. And still others are examples of devilish MOVIE MERCHANDISING, reviving damned villains and victims from feature films. These include comic books based on HELLRAISER, NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET, and BEETLEJUICE.

Modern comics such as these feature adventures in hell.

In the Information Age, computer users can find infernal comics on the Internet. The entertainment development group Toynetwork offers a variety of electronic comic books, “virtual toys,” and supernatural illustrations online. Toynetwork’s latest underworld creation is The Brotherhood, a group of fallen angels who are “too good to be bad” and are “purged from Hell” and sent to earth to battle the wicked INCUBUS. Browsers can read the strips, view graphics, and even download and print their favorite images. If the characters generate enough interest, they can be developed into action figures, ANIMATED CARTOONS, COMPUTER GAMES, or printed comic books.

The standard depiction of hell in most modern comics is of a rocky, harsh landscape bounded by flames and deep chasms. Winged or hooded DEMONS usually preside over the dark realm and delight in inflicting pain upon the damned. Often, the newly dead are unaware of their situation or are in denial and slowly come to realize their fate as their surroundings become increasingly horrific. Torments include physical, emotional, and psychological agonies. Overall, comic book hells are depicted as instruments of justice, inescapable abysses where villains ultimately pay for their vile deeds. They offer a sense of power, of retribution, to a society feeling increasingly overwhelmed—and outgunned—by violence.

COMICS For those who can laugh in the face of danger, hell serves as a basis for a host of dark gags. The inferno below has been the setting of literally thousands of comics, ranging from weekly strips to political cartoons to whimsical quips on GREETING CARDS.

Syndicated cartoonist Gary Larson offers the lighter side of damnation in a number of his Far Side cartoons. His collection includes dozens of sketches lampooning the underworld. One shows a split screen with an angel in the top half greeting new arrivals to paradise with, “Welcome to Heaven, here’s your harp,” while the bottom portion shows a demonic counterpart telling newcomers, “Welcome to Hell, here’s your accordion.” Another depicts a group of the inferno’s sweaty inhabitants watching a televised weather report, only to have the DEVIL inform them, “That cold front I told you about yesterday is just baaaaaaaaarely going to miss us.”

Another syndicated comic, Dilbert by Scott Adams, features a series of strips about the red-suited, horned DEMON Phil, the “Ruler of Heck.” This soft-boiled SATAN describes himself as the “Prince of Insufficient Light” and punisher of “minor offenses.” In one episode, Phil offers a dissatisfied employee one of two torments: either Dilbert will receive “eternal high pay” but be forced to watch all his hard work destroyed in front of him at the end of every day, or he will be appreciated and productive but endure “eternal poverty.” Phil’s attempt at punishing Dilbert backfires, however, when the long-suffering worker gleefully exclaims that either option is “better than my current job!”

Hell’s humorous side appears in a number of other publications. Rolling Stone magazine offers a regular series of Heaven and Hell cartoons by artist James T. Pendergrast. One features “Hell’s Diner” where the specialty of the house is fried liver nuggets. Another shows the “Devil’s cash machine,” complete with a place to “insert first born” before removing money.

A 1994 cartoon in the London Daily Telegraph depicts two damned men chatting amid the flames about the pitchfork-wielding demon who watches over them. “I’m not sure about his morals,” the speaker remarks, “but he’s very good at his job.” Similar devilish drawings by Charles Addams have appeared in The New Yorker for decades.

TWILIGHT ZONE MAGAZINE, published during the 1980s, ran numerous infernal comics, including lengthy stories told entirely in cartoon. Jim Ryan’s 1985 feature The Hook shows the misadventures of a pathetic comedian who finds employment in hell. After being fired from every club in New York, the performer is approached by a Mr. Jones, a mysterious promoter who promises to make him a star. The only condition is that the comic must work for what Jones refers to as “my organization.” He agrees and immediately catapults to superstardom. But when his two years of fame are up, the hapless comic must begin an eternal engagement at the “HADES Palladium.” His job is to torture hell’s inhabitants with his awful jokes. Satan congratulates Jones, telling him, “This guy is the greatest thing since FIRE AND BRIMSTONE.”

Hellish humor is a favorite among political satirists as well. A 1994 illustration by syndicated cartoonist Mike Luckovich shows a demon welcoming two terrorists—one Arab and one Israeli—to the smoldering underworld. He greets them with the salutation, “Welcome to your new homeland. You have to share it.” And former president Richard Nixon’s death generated a deluge of comics speculating on the controversial politician’s damnation.

Most of these drawings soften hell considerably, showing the underworld as a place of annoyances and discomforts rather than a realm of unceasing torture. Their continued popularity, in a world that frequently trivializes religion, attests to the importance that hell holds even in our modern culture.

COMMENTARY ON THE APOCALYPSE Commentary on the Apocalypse, a 786 manuscript by Spanish monk Beatus of Liebana, is a fantastic mix of biblical images, folklore, legend, and fantasy. The manuscript, which was painstakingly copied by hand repeatedly in the days before printing, also features numerous illustrations of heaven and hell. It is based on prophecies of the LAST JUDGMENT, when Jesus will call all the dead before him for final reckoning, as foretold in REVELATION.

The most striking picture shows the battle with APOLLYON (also called ABBADON), the dark angel of the “bottomless pit.” The winged DEMON wears a crown of flames as he rules an army of monstrous fiends. He and his minions are set against a patchwork of bright rectangles of red, green, burgundy, and yellow. They hungrily search the world for souls to devour. The picture’s vibrant colors and simple lines create a feeling of utter evil and impending doom, sure to chill the hearts of its medieval readers.

COMPUTER GAMES One of the biggest fads to hit America in recent times is the video game craze. Since the early days of Pong, children (and adults) all over the country have been mesmerized by the flickering lights and beeps and buzzes of computerized games. Many of these involve adventures in hell, the ultimate in virtual surreality.

One of the earliest interactive infernal computer games is TWILIGHT ZONE: Crossroads of the Imagination, patterned after the classic television series. Players find themselves in bizarre situations with few clues as to how to escape back into reality. The adventures are episodic but are ultimately linked through common elements. Like the show, the Twilight Zone game incorporates many unexpected twists and turns, landing players in mysterious otherworlds and infernal regions of peril.

Hell: A Cyberpunk Thriller takes video games a step further. The computer quest features film star Dennis Hopper’s digitized image as Mr. Beautiful, a modernized SATAN. The game follows the exploits of this twenty-second-century horned fiend as he deals in all manner of drugs, pornography, and other contraband. He distributes his wares to the living via the gate of hell, located in Washington, D.C. This action-packed adventure allows players to take on the role of a secret agent exploring the depths of the fiery underworld. Cyberpunk Thriller incorporates sex, violence, and armageddon in a flashy format of burning landscapes, blood-drenched pentagrams, and toothy GHOULS. Atmosphere effects include bursts of FIRE AND BRIMSTONE, three-dimensional DEMONS, and the disturbing sound of souls wailing in torment.

Writer CLIVE BARKER’s vision of hell has been adapted into Hellraiser: Virtual Hell, a slick adventure based on the Cenobites from Barker’s horror film HELLRAISER. Far from replicating the plot of the underworld movie, Virtual Hell is an interactive adventure that truly involves the player. And the stakes are high: The goal of the game is to retrieve your soul from hell after it is snatched by Pinhead, leader of the underworld ghouls. Virtual Hell even features the voice of Doug Bradley, who played Pinhead in the Hellraiser movies. Technological advancements allow the sounds and images of hell to take on a three-dimensional quality.

Another movie adapted for the computer screen is BEETLEJUICE, the offbeat comedy about the world of the dead. The game offers a Graveyard, Ghoul House, Afterlife Waiting Room, and five additional infernal levels through which players must pass. Obstacles to be overcome include ravenous Sand Worms, detached limbs, deadly scorpions, and “cranky ogres,” which must be eluded or diverted in order for players to advance.

The on-line computer adventure The Brotherhood features a band of rebel demons vanquishing hell. PANGEA CORPORATION—JOHN SCHULTE, JOHN BESMEHN, CHERLY ANN WONG.

Cyber enthusiasts can also catch a ride on the video game Hell Cab. It begins in the abysmal parking lot of Kennedy Airport in New York City. Once players have hailed “Raul’s taxi,” the aim is to pay the fare before the meter runs out on life. Those who fail (or die in the process) face eternal damnation. This surreal trip also takes players through time and space, to the days of ancient Rome and even to the age of dinosaurs. However, while the fare is adding up, the soul is ebbing away.

One of the most popular combat video games, Doom, inspired an infernal sequel, Doom II: Hell on Earth. Ads for the adventure claim that, “This time, the entire forces of the netherworld have overrun Earth. To save her, you must descend into the stygian depths of Hell itself!” This trip to the dark regions includes howling hounds, gruesome ghouls, and a cavernous underworld of fire.

In addition to the myriad of underworld CD-ROM games for use on personal computers, a new wave of infernal challenges is cresting via the Internet. New “game servers” and “chat rooms” are appearing almost daily, dedicated to hellish adventures such as Quake and Doom. On-line competitions allow players from all over the world to challenge each other—and the denizens of the abyss—without leaving the keyboard.

Amusement developers are likewise “auditioning” ideas on-line, allowing users to electronically sample computer games and “virtual toys” and offer feedback. Browsers can read game descriptions, view graphics, and print their favorite images, then forward comments and suggestions to the games’ creators. Concepts that generate enough interest can then be cultivated into computer games, toys, and other novelties.

Computer adventures set in hell offer players the ultimate thrill: saving themselves (and possibly the entire human race) from damnation. This takes the rescue motif, central to most computerized challenges, to its limit.

COUNTRY MUSIC Country music lyrics have been incorporating images of the grim afterlife into songs for decades. One of the first tuneful interpretations of the damned is the 1950s classic “Ghost Riders in the Sky.” The song describes a frightening gang of astral cowboys who descend upon a young wrangler, terrifying him with their ghastly appearance. The troupe warns the man that he, too, faces a dismal eternity of “trying to catch the DEVIL’s herd across an endless sky” if he does not change his ways.

More than three decades later, Confederate Railroad hit the charts with a ballad about the life and death of another hellbound rogue titled “If You Leave This Way You Can Never Go Back.” This tale of woe recounts the sins of a wanderer who has made a habit of hurting and alienating people who have tried to help him. He eventually murders a man, is sentenced to death, and coldly renounces all hope of salvation. The somber verse predicts “all through eternity you’ll roam alone” after living a life of such depravity and then refusing to repent.

Country music meets FAUST in the 1992 “The Devil Goes Back to Georgia” by Mark O’Connor. This song is a sequel to Charlie Daniel’s “The Devil Went Down to Georgia,” released a decade and a half earlier. In the reprise, SATAN returns to try once again to win the soul of Johnny, the fiddler who outperformed the dark lord in the first version. Johnny is now a “daddy” and is astonished that the devil is still determined to defeat him. This updated song includes passages from the Bible, prayers for victory, and a rebuke of the underworld ruler. In the MUSIC VIDEO for “The Devil Goes Back to Georgia,” the image of hell is achieved through shots of molten lava, fire, and mass destruction. Superstar Travis Tritt even makes a cameo experience as the fiendish master of the damned.

Traditional images of CHRISTIAN HELL also appear in 4 Runner’s “Cain’s Blood.” The song explores the inner struggle of a man who feels himself being pulled between the forces of good and evil, personified by his parents. Mama, a virtuous woman, preaches FIRE AND BRIMSTONE in hopes of preventing her son from turning out like his dad. Father, a chronic alcoholic and overall failure, freezes to death one cold night in a drunken stupor. Mama greets this news with the comment, “The devil can keep him warm,” conjuring images of a blazing inferno to which he has surely departed. Her son keeps this memory close at hand to remind him of the consequences of sin. The music video for “Cain’s Blood” illustrates this image with intermittent footage of flames leaping into the darkness.

Not all examples of lyrical hell are so serious. Hank Williams, Jr., makes known his feelings about the nature of the underworld in his ditty “If Heaven Ain’t Alot Like Dixie.” Fearing that paradise may not be a place of bass fishing, pro wrestling, and pork rinds, the singer begs instead, “Send me to Hell, or New York City, it’d be about the same to me.”

CREEP TO DEATH Poet Joseph Payne Brennan offers a collection of haunting works on the nature of the afterlife in his 1984 compilation Creep to Death. His words are drenched with a sense of impending doom as he speculates on what the underworld must be like, especially following existence in a world that is far from paradise. In “Hell: A Variation,” Brennan portrays the infernal region as a realm of ice rather than fire. He rejects the “scarlet DEVILS dancing” and “driving flames and smoke” in favor of a gloomy world of “gray and frozen hills” and the worst suffering, a “heart without hope.”

Brennan revisits the idea of bleak isolation and coldness of the human spirit in “My Nineteenth Nightmare.” In this poem, the speaker is condemned to relive the sorrow of his ill-fated “First Love” who is lost among “houses made of stone” on a desolate “frosty street.” “Winter Dusk” likens the gray skies and “briefer sun” of the cold season to the barren landscape of hell. Brennan likewise laments that “I shall rot, a wrinkled ape” after death in “Grottos of Horror” while his spirit languishes in eternal morose.

The poems in Creep to Death stir images of eternal suffering linked to human weakness and sorrow. Damnation is the failure of those who live in a frigid world devoid of emotion to form substantive relationships with one another. Brennan equates hell with despair, a concept shared by the poet Dante in his DIVINE COMEDY: THE INFERNO. His works also reflect theories of WILLIAM BLAKE and EMANUEL SWEDENBORG that joy or suffering—in this life as well as the next—result from the individual soul’s attitude rather than from a sentence imposed by some omnipotent deity.

CRIME Obsession with SATAN and with hell has been linked to nefarious crimes for centuries. During the Middle Ages, occultists were associated with grave robbing, necrophilia, desecration of sacred ground, and sometimes even human sacrifice. Confessed witch ISOBEL GOWDIE admitted to committing a number of atrocities as part of her coven activities, ranging from vandalism to murder. And although the time of widespread DEVIL worship has passed, ties to the netherworld continue to play a part in grisly acts. Allegiance to the inferno has factored into some of America’s most notorious crimes.

The most infamous example of this is the Manson family’s bloody murder spree in the late 1960s. Leader Charles Manson patterned his sect after the Church of the Final Judgment (also known as the Process), a Satanic cult founded by a former disciple of Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard. The Process’s California headquarters was just two blocks from the site of Manson’s 1967 commune, and the diabolical guru had extensive contact with the sect’s members (who continued to visit him in prison throughout the Tate–La Bianca murder trial). Manson adopted many of the Process’s rituals and beliefs, even embracing the BIKER gang Hell’s Angels as “soldiers of Armageddon.”

During the days leading up to the killings, Manson identified himself as both Satan and Christ interchangeably. One of his favorite lecture topics was the “bottomless pit,” a place he found quite glamorous. Manson described it as a “hole in Death Valley” where he would lead his chosen for their final reward. He frequently gave rambling speeches to “family members,” extolling the virtues of the pit and its endless sensual delights.

Many of Manson’s followers also had underworld ties. Cult member Bobby Beausoleil was a failed actor who had played the devil in the horror film LUCIFER Rising. Susan Atkins (who would later be convicted of participating in the murders) experienced visions of hell induced by LSD. She also claimed to be a witch who regularly took part in black masses and other infernal rituals. And one of the most frighteningly cold and unrepentant murderers, Charles “Tex” Watson, admitted that he had told his victims, “I am the Devil and I’m here to do the Devil’s business” before mutilating them.

The connection between hell and drug use had been established long before the 1960s. Author Aldous Huxley’s 1954 The Doors of Perception, and Heaven and Hell, clearly linked the two. Huxley concludes that many hallucinogenic drugs such as mescaline and LSD can cause powerful visions of the underworld. He cites one case where the user experiences terror “of being overwhelmed, of disintegrating under a pressure … greater than a mind could possibly bear.” Heaven and Hell also notes that Americans spend more on alcohol and cigarettes than on education in an attempt to “escape from selfhood.” But just as worry over contracting lung cancer does not stop us from smoking; the fear of hell does not stop us from committing evil acts. This is evident in the number, nature, and frequency of gruesome atrocities.

Author Joel McGinniss chronicles another infernal crime in his 1991 book Cruel Doubt. This factual account explores the murder and attempted murder of a prominent North Carolina couple. The surviving victim learned to her horror that her own son was responsible for her husband’s brutal slaughter (he had been savagely bludgeoned to death). A lengthy investigation revealed that the teen and his college friends, all heavy drug users, had gotten the idea for the killing from Dungeons and Dragons (D & D), an “otherworldly” role-playing GAME. Before moving on to murder, the troupe had frequently played in “Hell tunnels” (symbolic of the realm of the dead) as part of their obsession with the mystic game that mixes magic, spells, and the “upper” and “lower” worlds of spirits.

Perhaps the most tragic act of violence associated with Satanism and hell is the recent rash of teenage suicides. Teens, often feeling misunderstood by their parents, persecuted by their teachers, and confused by their lack of direction in life, become easy prey for demonic cults. Most do not truly believe in the doctrines; they are simply seeking acceptance and identity through association with hell. This rejection of traditional values also gives many a feeling of independence from their families, since they know that Mom and Dad would certainly never approve. Unfortunately, some discover that unholy allegiance is fatal, as suicide pacts are becoming more prevalent among these quasi-Satanic sects.

In 1992, a high school student from an affluent Maryland suburb suddenly stepped in front of a train as her shocked friends watched. In the aftermath of her death, her parents discovered the girl’s diary and were horrified to find numerous entries about Satan and hell. According to the account, the teenager proclaimed that Satan “is my father” and that he had taken her on tours of hell, where she longed to go permanently. Authorities at her high school learned that she was not the only student obsessed with the underworld and uncovered a free-form cult with Satanic beliefs. This led to probes throughout the country, and a startling number of high schools reported discovering demonic practices being conducted within their walls.

One of the difficulties in prosecuting crimes involving diabolical elements is the skepticism and denial by the general public. Few citizens want to admit that Satanism (and its gruesome practices) is truly a problem. It is too shocking for many mainstream Americans to contemplate, so they choose simply to deny the infernal connection and search instead for some other explanation. Only when violence erupts on a grand scale—such as with the Manson murders—does the public confront the notion that hell’s influence played a role in the crime.

CUPAY The Inca (originating from what is now Peru, Ecuador, and parts of Chile, Bolivia, and Argentina) believe that evil souls must face Cupay, the vicious god of death. Cupay lives in a dark cavern inside the earth and feeds on the spirits of the dead. He is a greedy deity whose lust for evil is insatiable, and he is ever trying to increase the size of his kingdom. He obtains souls by tricking humans into killing each other and committing other atrocities, thereby assuring their damnation.

Cupay is considered extremely evil; some legends say he demanded frequent human sacrifice. Early Christian missionaries called him the equivalent of the DEVIL and his realm the Inca counterpart of hell.