4

PUTNAM AND ARTIE.

PUTNAM WANTED to explore. His back and shoulders did not want to explore. His back wanted to die, it wanted to throw itself in a snowbank and freeze, it wanted an end to the constant burning and the sharp pain every time he moved. But he himself—his brain and heart—wanted to find the source of the salt, be the hero, make the world’s water drinkable again. And he would do this even if his back were twice as clawed up as it was now.

At least, he thought he would. He certainly wasn’t going to find another bear and test that idea.

He couldn’t see the claw marks himself, but Artie had assured him they were “impressive-looking.” Parallel tracks running from his right shoulder all the way down his back.

He took a deep breath and felt the wounds stretch slightly. He and Artie were walking along the salty creek, having left behind the place where the sweet water forked into it. There was no path, but the land was all grasses and bushes and scattered trees, and except for the constant hills, it wasn’t too difficult to navigate.

Around them the grasses rustled. There wasn’t a breeze in this place, exactly, but there was something more than a draft. Air was moving. And this morning, after the light dimmed for a couple of hours and then returned, he’d waked to a light rain, almost more of a drizzle.

Artie interrupted his thoughts. “Ahead. Look.”

They rounded a hill, and the sound of water suddenly increased to a dull roar. A waterfall.

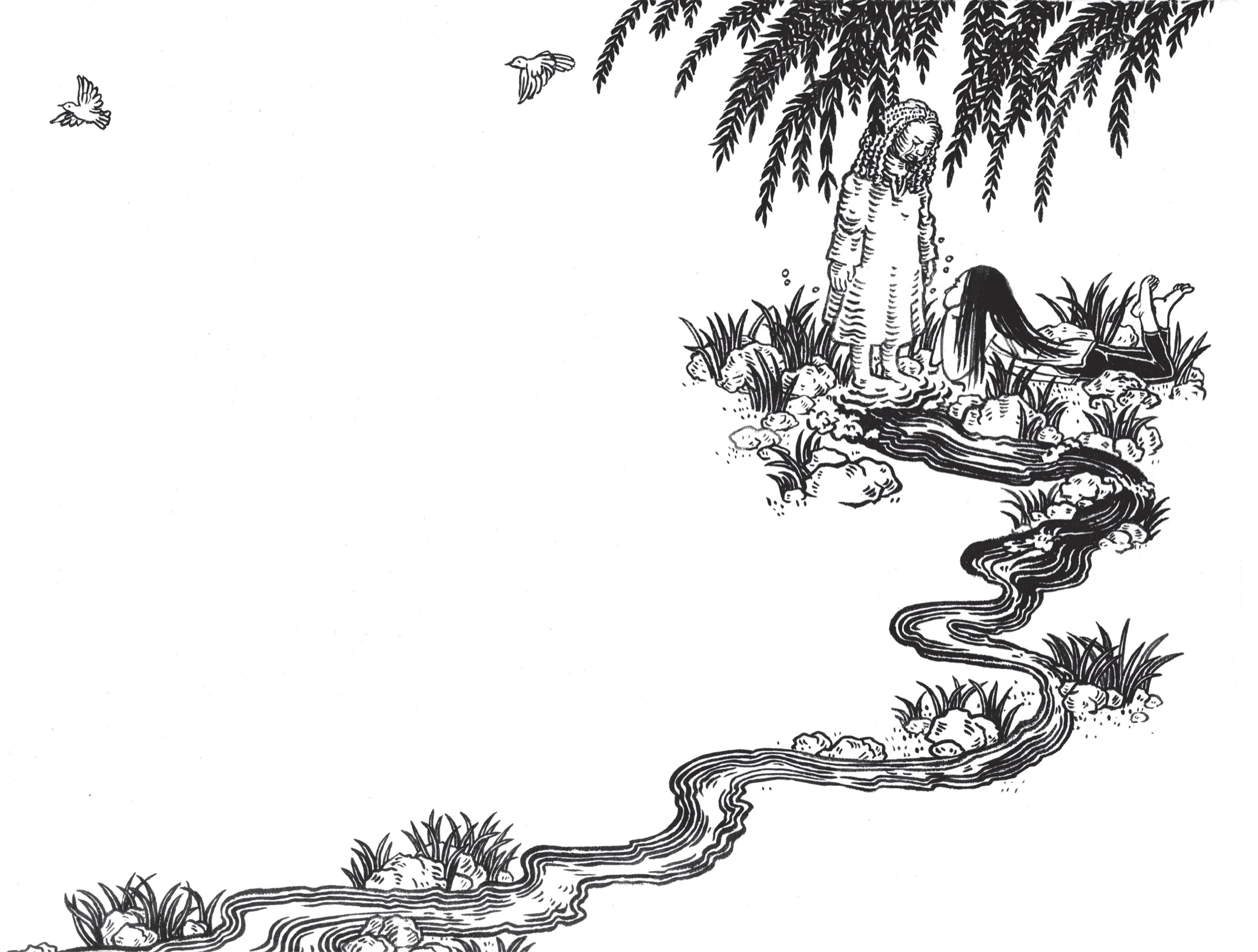

A waterfall, and next to it a tall willow tree. And something else.

A statue.

A statue of a woman.

THEY STUDIED the tree and the waterfall and especially the statue. The waterfall, as tall as a tree and maybe twice as far across as Putnam could have jumped, caused a fine mist to linger in the air, leaving everything in the area wet and verdant. Artie scrambled up the rocks on the side of the cascade and stood on top, reporting that as far as she could tell, the river that fed the waterfall wound its way out of some nearby hills.

The tree curved over the stream, casting restful shade all around the wide, pond-like area where the water foamed from its crash down the waterfall and before it began burbling away down the stream. The willow draped itself over the water almost like a woman pulling a bucket from the river for cooking, one limb trailing into the stream.

Artie returned from her climb and together they studied the statue, which stood straight and tall in the spray from the waterfall, dripping. It was the figure of a girl, maybe a couple of years older than Putnam and Artie. She wore a simple old-fashioned dress, no shoes, no cold-weather gear. Arms at her sides, hands open. Something about the posture seemed wrong, as if she’d been told to pose. Uncomfortable. Putnam thought she looked angry, and then he thought sad, and then he thought—he wasn’t sure. All the mist condensing and dripping down her face made her expression impossible to read.

As he studied the statue, he realized the problem wasn’t just that the statue was standing stiffly, but that, with the water running down it in constant rivulets, it had an odd feeling of movement to it. The overall impression was troubling; it unsettled him.

He turned and walked away, but Artie called him back. “Did you notice . . . ?”

“Notice what?” He looked at Artie, not the sculpture.

“She looks . . . she looks like Raftworld. Like your people, I mean. Like Raftworlders.”

He forced himself to look again at the girl. The waterfall misted her head, and water dripped down her cheeks in tracks. Artie was right. She did have a classic look about her—not Islander, with their straighter hair and sharper features, but Raftworlder, with tightly-curled hair, here pulled into braids, and a warmer (he thought) face. Well, maybe not warmer; maybe just a face he was more used to. Artie’s face certainly seemed warmer now than he’d originally thought.

“She does look Raftworlder, right?” Artie said. “The braids?”

Putnam nodded. “Old-fashioned hair and clothes for Raftworld. But yeah. I can see it.” He turned away again, wanting to get out of here, away from the misty water, away from the weird statue.

“Isn’t that weird, though?” Artie said exactly the word he was thinking, but it sounded like she meant something different by it. “I mean, doesn’t it make you wonder? How she got here? Who carved her? And look—how is she even standing up?”

“What do you mean?”

“There’s no base. For the sculpture. She’s just standing on the wet ground. How is she even staying up? How is she not falling over or sliding into the river?”

The figure stood precariously close to the water, on the very edge of the stream. Sand shifted around her feet, and water swirled at her toes, but she did not shift.

Not she, it. Just a statue.

“It is strange to find a statue where there’s no people,” he said, cautiously agreeing. “I mean, I guess that proves that someone, maybe someone from Raftworld, arrived here a long time ago . . .”

“And carved a statue?” Artie sounded almost accusing. “Why?”

“I don’t know. I’m tired.” And it was true. Putnam suddenly felt exhausted, like he couldn’t think clearly, and like he could barely take another step. And he just didn’t want to talk about the statue right now. “I need to . . . find somewhere to sit.”

Artie, who’d been crouching to examine the woman’s feet, jumped up. “Oh, I’m sorry. I should have thought. You need to rest. Let’s find a place to settle for a while.”

“Away from the water,” said Putnam, shivering. The mist suddenly felt cold.

Artie ran off and reappeared a moment later. “Just up here.” She led him uphill, away from the waterfall and the tree and the sculpture, to a warm sun-dappled spot in a meadow under some tall bushes, where she spread a cape-blanket and said, “Sleep. I’ll find some more food, and I’ll come back soon.”

He nodded, so tired he couldn’t argue, couldn’t suggest that he’d look for food, too. Could only sleep in the sunshine.

WHILE PUTNAM slept, Artie went exploring. First she found more berries and carrots, and then she found some small tomatoes and something that looked like oversize apples. She carefully picked two; she’d try them in small bites before letting Putnam eat any.

She also found an aloe plant and broke off a couple of the fat, gel-filled leaves. When Putnam woke, she could help his back heal. Aloe worked wonders; she’d used it herself many times.

When she went back to Putnam, he was still sleeping. She tied the food into a blanket corner and left. Just for a short time. Not for long.

She returned to the statue.

There was something that drew her back, and she wasn’t sure what it was. The expression on the girl’s face? The fact that she seemed like a Raftworlder? That she looked only a couple of years older than Artie herself? The hopeless set of her shoulders?

The statue was in the same place as they left it. Of course it was. It was dripping with mist and spray from the waterfall. Artie stood in front of it, her heels in the shallow water of the stream, and looked it in the face. She was shorter than the statue, but not by a whole lot. The stone girl stared downstream. The water blurred her features, made her look sad. Maybe that was what was bothering Artie: all the mist made it look like the girl was crying.

Artie reached up with her sleeve—damp by now from the waterfall mist, too, but she found a dry spot on the inside of her forearm—and carefully wiped the statue’s face. There. That was better. The face looked so much more peaceful without the water dripping down it.

Except.

Except it was still dripping.

The light mist hung in the air—barely a breath of water; it would have to build up for some time to form rivulets down the statue’s face. And yet the statue was crying.

The statue was crying.

Tears were coming out of her eyes. What Artie had thought was mist on her face wasn’t mist at all—or rather, it wasn’t just mist.

Artie watched closely as the tears ran down the girl’s face. Then down her neck and chest and torso and leg. The tears ran off her foot and into the water. The tears ran into the stream . . . that eventually fed into the ocean.

Tears!

A wild thought in her head, Artie stepped back into the water. She walked a couple of yards downstream of the statue, dipped her hands into the water, and scooped a gulp into her mouth. Spat it out again. Salt. Salt as strong as could be.

She walked back to the statue and then upstream several yards, where she repeated the experiment. She drank. And drank again.

The water was clean and pure. Upriver from the statue, it was sweet, the way water should be.

ARTIE THOUGHT about running back to Putnam to tell him that she’d located the source of the salt. But what could they do to fix it? What would Putnam want to do? Chop down the statue? Destroy it?

No, they couldn’t destroy the statue. It—she—was crying. Artie didn’t know what the right thing would be to do, but she knew that killing the statue wasn’t it.

Because, yes, it felt like they would be killing someone. Artie didn’t know why. No, she did: there were stories on her own island of people who’d been cursed and turned to statues. Fairy tales, she’d always thought. But now, with this weeping statue in front of her, she thought there might be some truth to the stories.

Maybe, just maybe, this statue was once a real person.

If Artie could just get the statue away from the water, then she could keep it from infecting the ocean with more salt while she considered what to do next. She pushed as hard as she could, her shoulder set against the stone, but she couldn’t move the rock. The statue wasn’t fixed to a base, but it was locked in place somehow. She couldn’t even jiggle it.

Exhausted and sore from pushing, Artie flopped down on a big stone that lay partly in the downstream water and rested her head on her elbows. It seemed almost like the statue was looking directly at her face.

It was still crying.

“Why?” Artie said.

She knew the statue wouldn’t answer. She wasn’t stupid. But somehow it felt—like maybe the statue would listen. Like there could be a one-sided conversation that might actually go somewhere.

“We found you,” she said, trying to be conversational, “almost by accident. I mean, my friend was looking for you. But he didn’t know he was looking for you. He wants to fix the salty sea. To change it back to fresh water. That’s why he’s on this trip in the first place.”

The statue’s tears continued to fall. She was expressionless. Studying her, Artie could see how asymmetrical her face and body were. She’d probably never been thought a beauty. Misshapen head. Turned-in feet. And on her arm, a set of claw marks similar to Putnam’s.

Had she also faced a bear, before she found this cavern? Had the tunnel saved her as well?

“Maybe you ran away like I did. That’s how you ended up here.” The statue couldn’t hear her, not really—and definitely couldn’t respond. Artie rolled her sleeve to show the old burn marks on her arms and brushed her hair back to show her face. With her new bruises from the tunnel, she was surely ugly enough to impress this statue. “I don’t have claw marks like you and Putnam. But—I do, kind of.” She’d had her own bear, in a way.

The world vibrated with the not-quite-silence of stream and waterfall and birdsong. Artie looked around. This underworld was good. Maybe this girl had once lived here in peace, long ago. And now Artie was here, safe from all kinds of monsters.

“I’ll figure something out,” she said, half to herself and half to the statue. “I won’t let Putnam destroy you.”

The statue almost seemed to sway. But no, it was Artie, sliding face-first down the wet rock. She stopped herself by plunging her hands into the water and hopping up. It was time to go anyway. Putnam might be awake.

“I’ll be back as soon as I can,” she said. It felt nice to talk to the statue. Like she understood. Artie turned and waved before heading back to Putnam.