From the beginning, Ted Geisel loved two things more than all else: funny animals and silly words.

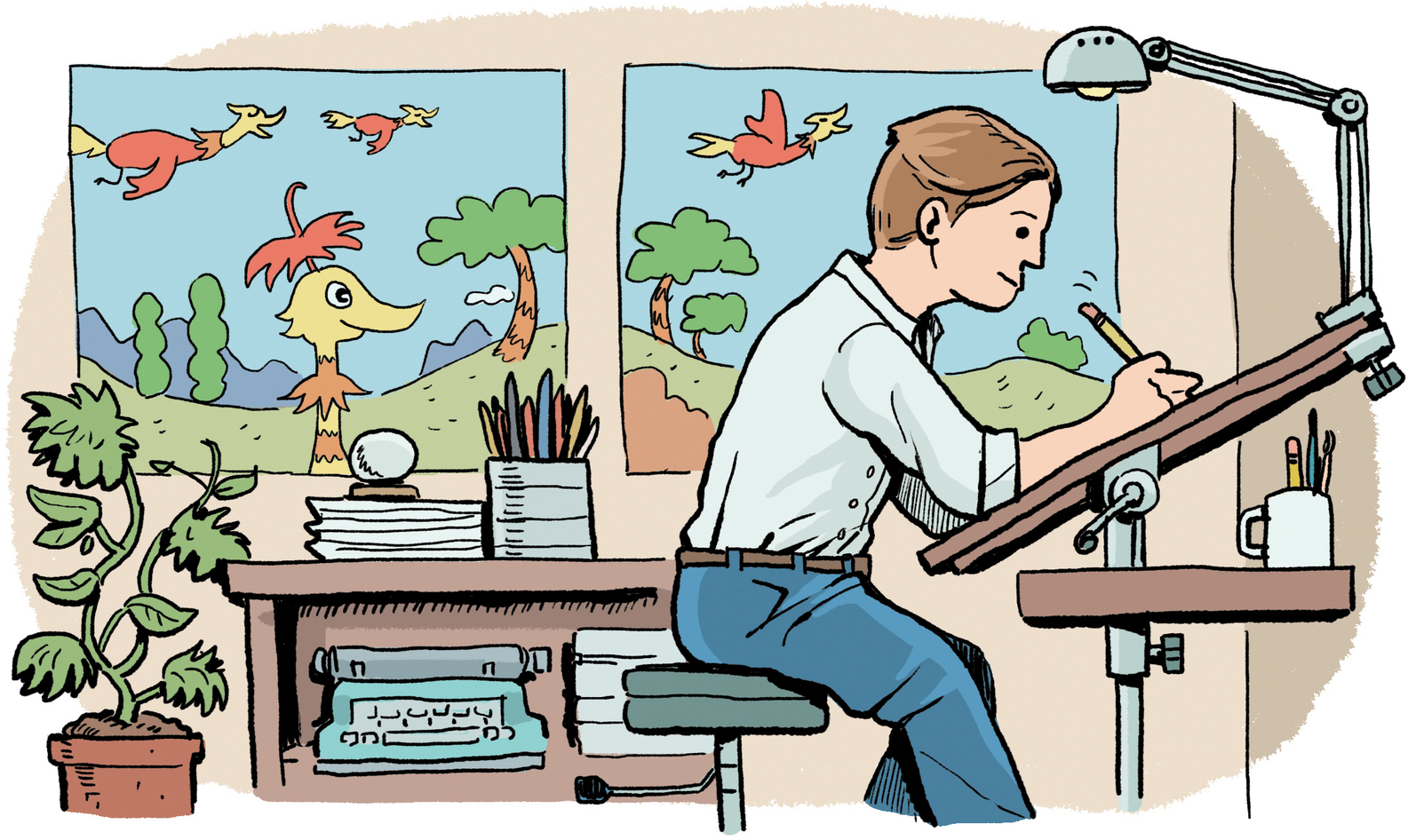

When Ted was a boy, he lived six blocks away from the town zoo. On summer days, when school was out, he’d head over to the zoo and spend hours gazing at the monkeys in their monkey house and the lions in their cages. Then he’d rush home and—with his parents’ permission—draw pictures of the animals in crayon on his bedroom walls.

The surprising thing was that Ted’s animals looked nothing like the real ones. The creatures resembled cartoons—a duck with angel wings for example. He would label each one with its own nonsensical name. One of his favorite imaginary beasts was an elephant with nine-foot-long ears, which he called a Wynnmph.

Ted’s love of inventive words and funny sayings ran in the family. His grandfather had immigrated to America from Germany in the mid-1800s. Together with a man named Christian Kalmbach, he founded a brewery called Kalmbach and Geisel, which sounded a lot like “Come Back and Guzzle.” So that’s what people started calling it. By the time Ted was born, in 1904, his grandfather’s brewery was one of the largest and most successful in New England. Its beer was delivered all over Springfield in a black and gold wagon pulled by Clydesdale horses.

Ted’s father helped run the business, and in his spare time he invented things and gave them funny names. His inventions included a machine for strengthening the muscles in a person’s forearm, and a device that prevented flies from getting into beer barrels. Ted’s favorite was a mysterious contraption called the Silk-Stocking-Back-Seam-Wrong-Detecting Mirror.

Ted’s older sister shared his love for weird and wacky words. Her name was Margaretha, but she insisted that everyone call her Marnie Mecca Ding Ding Guy. Nobody knows why.

Ted’s mother’s specialty was stringing words into a rhythm called a meter. Back when she was young, Henrietta Seuss Geisel had worked in her family’s bakery. Later, after she married Ted’s father, Henrietta would sing her infant son a lullaby about the pies she used to sell: “Apple, mince, lemon…peach, apricot, pineapple…blueberry, coconut, custard, and SQUASH!” The meter stuck in Ted’s head, helping him remember all the different kinds of pies.

Besides his love of wordplay, Ted had yet another reason for being fascinated with language. He was bilingual, meaning that he spoke two languages, German and English. At Christmastime, the family sang “Stille Nacht” instead of “Silent Night” and “O Tannenbaum” instead of “O Christmas Tree.” For dinner, Ted ate German sausages, and he learned to appreciate the many varieties of liverwurst.

Ted never thought much about his German background, or how it made him different from other kids in Springfield. But that all changed when Ted turned thirteen. That year the United States went to war with Germany. A patriotic fervor took hold in America, and some people directed their anger toward the German Americans in their communities.

Families like the Geisels became objects of suspicion. People feared they might be spies or traitors secretly loyal to the German ruler, Kaiser Wilhelm. Some U.S. government officials encouraged such anti-German sentiment. A special committee of Congress officially renamed frankfurters “hot dogs,” and sauerkraut became “liberty cabbage.”

The wave of misplaced patriotism soon reached Springfield. Town leaders ordered that all German-language books be removed from the library. The local symphony stopped playing music by German composers. The pastor at the local Lutheran church started preaching in English instead of German. Some of Ted’s classmates teased him for speaking German at home. They called him the “Kaiser’s Kid” and threw stones at him.

Ted refused to be bullied. Over the next few months, he set out to prove that German Americans could be just as patriotic as anyone else—even more so. He collected scraps of tin for the war effort and planted a victory garden in his yard.

When his Boy Scout troop asked members to sell war bonds, Ted was among the first to volunteer. For the next several weeks, he went door to door, up and down Mulberry Street, convincing the citizens of Springfield to buy bonds to support American soldiers fighting in the war. Ted even persuaded his own grandfather to pledge $1,000.

Ted was so successful that he was named one of Springfield’s top ten Boy Scout war-bonds salesmen. To honor the boys, a special ceremony was held in the town’s auditorium. Presenting the awards was a very special master of ceremonies: former U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt.

On the day of the event, thousands of townspeople crowded the auditorium. Ted was on the stage, along with his scoutmaster and the nine other honorees. As patriotic music played, President Roosevelt approached the podium. He delivered a rousing welcome speech and then proceeded down the line to pin a medal on each boy’s chest.

When he got to Ted, however, he had no more medals to pin! Ted stood there awkwardly. He was so embarrassed.

As it turned out, Ted’s scoutmaster had miscounted, giving the president only nine medals instead of ten. Ted had the misfortune of being last in line.

The scoutmaster hastily whisked Ted off the stage. Even though it was just bad luck, Ted felt like he was being punished for being German. The memory of this mortifying moment never faded. For the rest of his life, Ted feared appearing onstage in front of large crowds.

By the time the war ended, Ted was a sophomore in high school. Springfield’s German American citizens went back to their normal lives; few spoke of the discrimination they had faced. But Ted never forgot. He began drawing cartoons for the school newspaper. The drawings combined his love of wordplay and fantastic creatures with his opinions about injustice and inequality.

To protect his true identity, Ted signed his cartoons “T. S. LeSieg” (LeSieg was Geisel spelled backward). In time, he would adopt the more famous pen name—Dr. Seuss—by which we know him today.

In 1921, Ted left Springfield to attend Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. Even though he was on his way to becoming an adult, memories of his hometown and the people there continued to influence his writing and his art. In fact, characters and places recalling those he knew from Springfield appear in Ted’s first book, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, and animals inspired by the zoo that he used to visit populate the stories of Horton Hears a Who. Two of his most famous characters, the Grinch and the Cat in the Hat, were based on the person Ted knew best of all—himself!

No matter how fanciful his stories became, to Ted they seemed as familiar as the Springfield town square or the shop around the corner. “Why write about Never-Never Lands that you’ve never seen,” he once said, “when all around you have a real Never-Never Land that you know about and understand?”

A strong sensitivity to social injustice remained an important part of Ted’s work as Dr. Seuss. In such books as The Sneetches and Yertle the Turtle, Ted warned about the dangers of discrimination, using words that readers of all ages can understand. He wrote in a special language that he had developed all by himself—and shared a lesson he had learned firsthand—as a kid growing up on Mulberry Street.