Figure: 8.1.

CREDIT: O’SULLIVAN SOLUTIONS

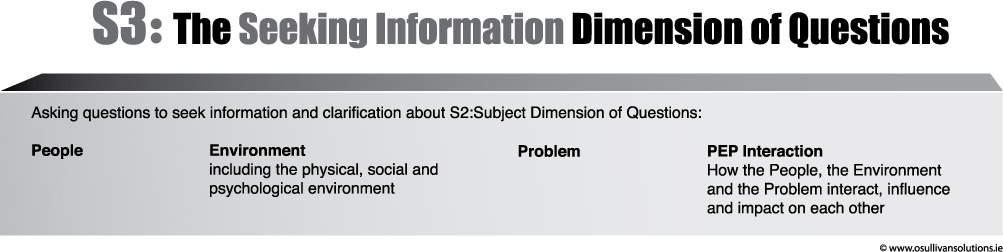

THE S3: SEEKING INFORMATION QUESTIONS strategically target the information that is required from the parties for the conversations needed for the mediation process. S3 questions directly seek information that may already be known or unknown by each of the parties. They also clarify existing information. S3 questions invite the party’s perspective on the conflict. Creating a paradigm shift is not the intended goal when asking an S3 question, but it could be an unanticipated outcome.

When developing, and testing a hypothesis about what may be happening in a conflict between parties, an effective mediator needs to develop and ask questions that will also contradict their most likely hypothesis. If they only concentrate on looking for the information that confirms their hypothesis, then the amount of information gained will be limited.

The philosopher and statistician Nassim Nicholas Taleb, the Dean’s Professor in the Sciences of Uncertainty at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, explores this theory in The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable.35 This is how he describes a black swan:

Firstly, it [a black swan] is an outlier, as it lies outside the realms of regular expectations, because nothing in the past can convincingly point to its possibility. Secondly, it carries an extreme impact. Thirdly, despite its outlier status, human nature makes us concoct explanations for its occurrence, after the fact, making it explainable and predictable.

To introduce as much information as possible, a mediator needs to be aware of this concept and the importance of looking for not only that which the parties don’t know, but also that which the parties don’t know they don’t know. And the mediator needs to be actively open to asking searching questions to discredit their own hypothesis, in order to introduce as broad a range of information as possible into the mediation discussions.

S3: Seeking Information questions can be asked during all stages of the mediation process, but particularly at the start and during the storytelling stage, when the mediator is gathering information from the parties. The responses to these questions will form the pool of information about the conflict from which S4: Shift Thinking Dimension of questions can then be asked.

Examples of S3: Seeking Information Questions

People

■ You mention that you have not slept well since the start of the conflict, how did you sleep before this conflict? Specifically, what is it about the conflict that keeps you awake at night?

■ You mentioned that Karen intrudes on your work; can you give me a specific example of what you mean?

Environment

■ When you say that it all went wrong at that point, at what point specifically do you mean?

■ Is it the context in which this happened that is concerning you the most, or is there a larger concern for you?

■ What is it about that context that made it worse?

Problem

■ Can you please define for me exactly what the problem is, so that I understand clearly?

■ What is the cause of this problem?

■ How does this problem compare to the problem that you described earlier in the session?

PEP Interaction

■ When you say that the mood of those in the office changes when the manager is in the room, how does that dynamic change?

■ What difference does this make for you?

■ To what would you attribute this change?

The responses to these questions will form the pool of information about the conflict from which S4: Shift Thinking Dimension of Questions can be asked.

Here are some examples of questions that will result in new information being heard by the parties.

People

■ You say that this has been a tough time for you. Can you tell me a little bit more?

■ How was your relationship at the time when you both started to work together?

■ What contributed to your relationship breaking down? How did this impact on each of you?

Environment

■ Can you give me an example of when/where/in what context this issue arises?

■ What is it about this context that makes the conflict worse for you?

■ What else contributes to it?

■ What concerns you most about this?

Problem

■ What is your understanding of the problem or issue?

■ You say you had a good relationship with each other before this happened, what made this a problem for you?

■ What makes the problem worse?

PEP Interaction

■ How does the environment in which you are working contribute to the problem?

■ How does this problem affect the organization and/or its productivity?

■ What would others in the department say about your relationship and its impact on the organization?

There are two additional techniques that can be coupled with S3: Seeking Information Questions:

1. Working with Metaphor

Asking S3 Questions by incorporating any metaphors used by a party into the follow-up question

2. Clean Language

Asking S3 Questions by using Clean Language

Both techniques facilitate a mediator to clarify existing information and uncover new information. These techniques are primarily designed to deliver clear and accurate information that connects specifically to the experiences of the parties. While the goal of these questions is to bring new information into the process, this in itself could create a paradigm shift.

Asking questions that include the metaphors used by the parties helps mediators to connect with a party’s symbolic language so that the specifics of what a party is trying to voice can be clearly identified. The metaphors used by parties are their inner reality and can be the language of their unconscious minds. When metaphors are used by a party, they either communicate exactly that which was intended, or that which may have been intended, but is not yet conscious to the party. By repeating the metaphor used by a party, the mediator will help to maintain the party’s link to their unconscious mind and potentially bring those thoughts to consciousness, if appropriate.

The purpose of working with metaphor in mediation is:

✓ To support parties to identify or voice the core of their experience.

✓ To facilitate a mediator and the other party to hear clearly what a party in mediation is trying to voice.

✓ To facilitate a party to make connections with other experiences when their feelings were similar (but only when appropriate to a mediation process), as this introduces context and perspective to their current issue.

✓ To support a party to move toward future agreement by using their metaphoric language in a way that connects specifically to their experiences, so that the solutions that are agreed are appropriate to those experiences.

In their book Clean Language: Revealing Metaphors and Opening Minds,36 Wendy Sullivan and Judy Rees put forward some suggestions as to how to identify a metaphor:

1. If a sentence starts with words that describe the comparison of what a person is experiencing with something else, then it is a metaphor.

Example:

It’s like…

or

It’s as though…

or

It’s as if…

2. If what is being described is referring to a different aspect of a person’s life, it is probably a metaphor.

Example:

When a person is talking about their relationship with their boss and says:

It’s like when I used to have fights with my father...

or

It’s like when I am traveling and someone pushes in front of me in the lineup...

3. If the words used refer to space or force, then it is probably a metaphor.

Example:

traveling along the bumpy road of life

bringing it solidly back to ground...

4. If a person uses a sentence such as “We are standing at a crossroads,” and if they are not standing at a crossroads, then this is a metaphor.

Metaphors can be communicated in single words or through expressions or stories and can help a mediator understand a person’s experience. Metaphors often reflect the interplay between our physical world and our thinking.

Example of the use of a metaphor by a party in mediation:

Negative metaphor: I feel a great weight on my back with this project.

Positive metaphor: It is like the load has become lighter.

The metaphors that are used for powerful, strong and deep negative emotions tend to be vivid and obvious and need to be managed very carefully by mediators, particularly those who are new to mediation practice or who are not sufficiently experienced in working with deep emotions.

■ A mediator needs to use the separate private meeting, before the joint meeting, to identify any deep negative emotions in a party so that these are not inadvertently exposed during the joint session.

■ Do not work with or focus on metaphors that use strong negative emotions as this may evoke the deep emotional state of a party that is associated with those memories.

Examples of strong negative emotions that may signal deep distress or depression in a person are:

■ I am in a dark place and I cannot get out of it. It is as if I have been abused all over again like when I was a child.

Should a mediator inadvertently delve into a party’s powerful or deep negative emotions, then it is important to acknowledge what the party said, while using empathic body language and a slow, gentle and quiet tone of voice:

Mediator:

Karen, I hear you saying that you are in a dark place and that it is as if you have been abused all over again like when you were a child, and from what you are saying it looks like it has had a deep impact on you… (Pause)

I am wondering what might need to happen to ensure that your expressed concerns about the future can be addressed appropriately so that you do not feel vulnerable at work?

However, there are many times when it can be useful and valuable to strategically deepen a strong emotion. For example, if a party says that they feel guilty or regretful about something they said or did during a conflict, then exploring these emotions at a deeper level will create understanding and acceptance between parties.

Using the metaphor that a party uses, and reflecting those exact words back to the them, indicates to a party that a mediator is deeply listening to, and hearing, what they are saying. The development of this rapport helps the mediator gain the trust of the party, which creates a climate where a party will feel encouraged to say openly and honestly what is affecting them in the conflict.

Here is an example of a flow of questions that can be asked using a range of open questions from the S Questions Model.

■ Tom, you mentioned several times that you felt like tearing your hair out… May I ask you more about it, please? What do you mean specifically when you say that you felt you were tearing your hair out because of all this work?

■ What is it like for you to feel that you are tearing your hair out with all this work?

■ What do you feel is contributing to you feeling like tearing your hair out about this work?

■ What exactly happened that led you to feel like you needed to tear your hair out?

■ To what were you specifically reacting?

■ What was happening for you before you felt like tearing your hair out?

■ What were you thinking when you felt like tearing your hair out?

■ What sort of things usually cause this reaction in you?

■ What were you worried or concerned about?

■ With what is your feeling of tearing your hair out usually connected?

■ Are there other situations when you feel like tearing your hair out?

■ How is this experience similar or different?

■ What were you thinking when you tore your hair out in other situations?

■ What was distinctive about feeling like tearing your hair out this time?

■ At the time, what would have let the other person know that you felt like tearing your hair out?

■ And what might the other person have been thinking, feeling, experiencing when you felt like tearing your hair out?

■ When you reacted like you did, what do you think the other party thought that meant? How might their interpretation compare to what your intention had been?

This section will explore the use of the Clean Language question technique as a method for seeking information. This technique aims to ensure that a mediator’s own perceptions, assumptions or bias do not taint the questions they pose.

Clean Language37 questioning was created and developed by David Grove. What he aimed to do was quite specific: to introduce as few of his own assumptions and metaphors as possible, giving the client (or patient) maximum freedom for their own thinking. He didn’t claim to be able to work without influence or bias, only that he aimed to minimize it. Clean Language questions facilitate parties to make connections with information related to their experience.

Wendy Sullivan and Judy Rees describe this further in their book Clean Language. The authors clearly and comprehensively illustrate the method for asking questions to ensure that the perceptions, assumptions or biases of the person asking the question do not influence the type of question they pose.

Despite our best intentions, mediators can sometimes include some of our own assumptions when we construct questions without using Clean Language. In the following example, the mediator’s assumption was that the expectations of the party were the cause of the problem:

Party says:

I felt really dragged down after that.

Mediator:

How did your expectations contribute to you feeling dragged down?

On the other hand, using Clean Language ensures that any questions asked are justified by the logic of what a party has described. A Clean Language question is not tainted by a mediator’s assumptions:

Party says:

I felt really dragged down after that.

Example of a mediator’s Clean Language question that only uses the party’s own words:

What kind of dragged down was that?

Was there anything else about that feeling of being dragged down?

The core or basic Clean Language questions are divided into three categories; see the examples of each category in the table.

a) Developing questions

b) Sequence and source questions

c) Intention questions

Core or Basic Clean Language Questions |

The Purpose of Clean Language Questions |

Developing Questions Developing questions facilitate a party to make connections with something else that they either know or have experienced previously. |

|

What kind of X (is that X)? Is there anything else about X? Where is X? and/or whereabouts is X? Is there a relationship between X and Y? When X... what happens to Y? That’s X like what? |

These questions draw out a descriptive narrative in a focused way by asking for a description of X. Regarding the question “Where is X?” the authors state that if there is something in someone’s thoughts, then it is nearly certain to be located somewhere, but often we are not aware that our thoughts have locations in space. |

Sequence and Source Questions These questions are asked about what happened before, during and after X happened. They allow parties to make connections with any missing information. |

|

Then what happens? What happens just before X? Where could X come from? |

The purpose of “sequence and source” questions is to: a) Clarify the order and pattern in which things happen b) Clarify from where the symbol used (metaphor) comes c) Make connections with other information or experiences that may be relevant to the current experience of the party |

Intention Questions These questions facilitate the party to think of what they would like for the future. |

|

What would X like to happen? What needs to happen for X? Can X (happen)? |

These questions focus on solutions and the future. |

Working with Metaphor Using Clean Language Questions

Developing Questions |

|

Mediator: |

What is it about this issue that you would like to solve? |

Party: |

I would like to be able to push forward without the past problems I have had with Tom. |

Mediator: |

What kind of pushing forward? |

Party: |

Pushing forward without all the past tension between us. A healthy pushing forward. |

Mediator: |

Is there anything else about pushing forward? |

Party: |

Yes, I think it would bring us to a much better place, if we both decided to give it a try. |

Mediator: |

Whereabouts is that pushing forward? |

Party: |

It’s right there in front of me. I can see it very clearly. |

Mediator: |

Is there a relationship between pushing forward and the concerns you raised earlier? |

Party: |

I think if we both push forward, Tom and I will create a much better working relationship. Then I think I will have the capacity to achieve a lot more in work as I won’t be stressed all the time. |

Mediator: |

When you are pushing forward, what happens to Tom? |

Party: |

He is there pushing against me! |

Mediator: |

And that’s like what? |

Party: |

Well, like we are fighting against each other all the time, instead of working in harmony. |

Sequence and Source Questions |

|

Mediator: |

Then what happens? |

Party: |

Well, the tension escalates, and we are both shouting at one another. |

Mediator: |

And then what happens? |

Party: |

I am afraid that the project will not get completed properly and I will be blamed. |

Mediator: |

Where could that come from? |

Party: |

When something like this happened before, I nearly lost my job and it was not my fault. It had a devastating impact on me. |

Intention Questions |

|

Mediator: |

And then what would you like to have happen with that pushing against you by Tom? |

Party: |

That Tom and I could push together in the same direction, and then we would both get our work done more effectively. |

Mediator: |

What needs to happen to achieve that? |

Party: |

We need to sit down and look at our job descriptions and work out where the overlap is. We need to do this with our supervisor. Then we need to look at some of the instances that havecaused us to disagree with each other and see how they fit in with our updated job descriptions. |

Mediator: |

And then? |

Party: |

We need to talk about what we will do if we push against each other again. We need a backup plan. |

Mediator: |

And can that happen? |

Party: |

|