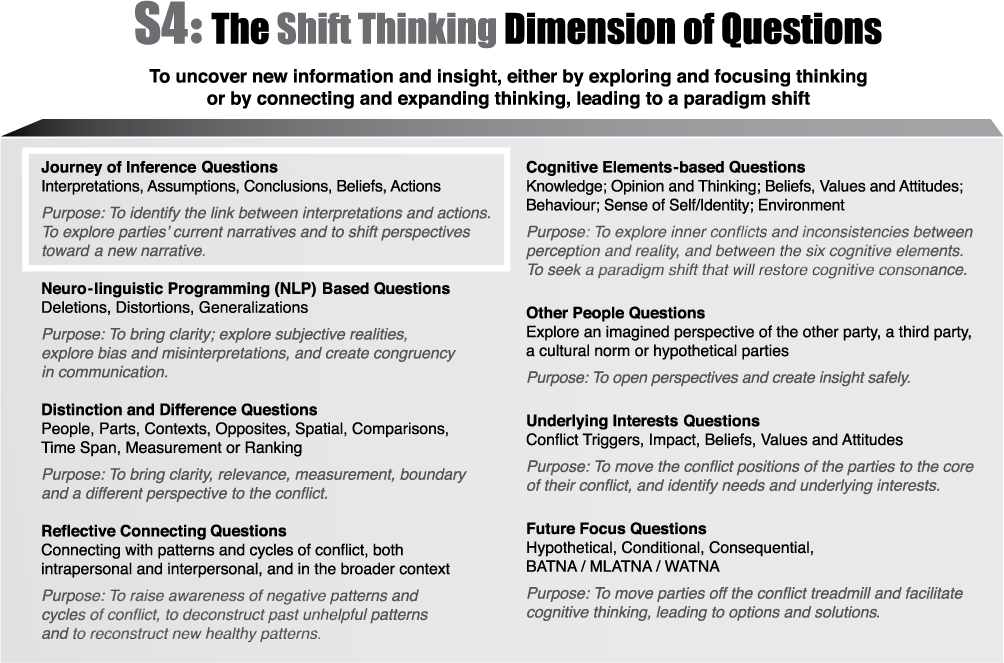

Figure: 10.1.

CREDIT: O’SULLIVAN SOLUTIONS

JOURNEY OF INFERENCE QUESTIONS take a party through the information they selected during a precipitating event; the interpretations they made about that information; the assumptions they made; and the conclusions they then reached which, in turn, informed any decisions or actions they took. These questions also explore the beliefs of a party and how these beliefs may have influenced their Journey of Inference.

As described in Chapter 2, the decisions or actions of parties are governed by the amount and type of information their brains absorb and the emotions that surface for them while they are interpreting the limited amount of information they do process. Our brains tend to absorb information that affirms our own perspective and paradigm, and we seldom absorb information that challenges it.

The parties make their own unique Journeys of Inference based on their unique perspectives and beliefs. Journey of Inference questions are used to explore the thinking process that parties go through, usually unconsciously, to get from the experiencing of an event to their resulting judgments, decisions or actions.

Definitions of Interpretations, Assumptions, Conclusions and Beliefs

Interpretation |

The action of explaining the meaning of something |

Assumption |

A thing that is accepted as true, or as certain to happen, without proof |

Conclusion |

A judgement or decision |

Belief |

A feeling that something is true, even though it may be unproven or irrational. Beliefs are built up over years, and they can influence assumptions. But assumptions cannot influence beliefs. |

From the experience or event to the moment that a decision is made because of that experience, the journey of thinking takes place in the mind. Our understanding of the meaning of what happened, the assumptions we make, the conclusions we reach and the beliefs we form are all thoughts inside our mind.

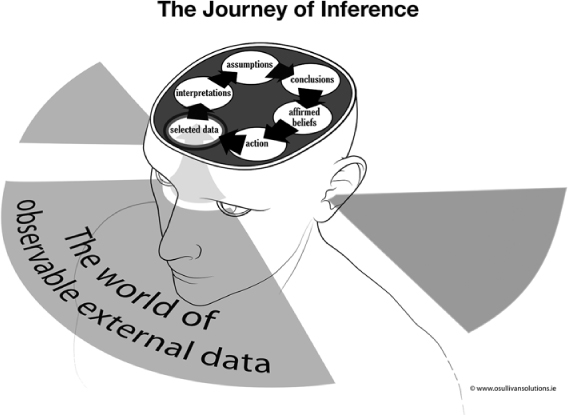

Figure: 10.2.

CREDIT: O’SULLIVAN SOLUTIONS

It is within this reality that we then live. In other words, we live inside the constraints of our own interpretation of the experience. If we do not possess finely tuned personal insight, and if we are not sufficiently emotionally intelligent, we may take this journey without any self-reflection, self-questioning or seeking any contradictory evidence.

Most conflicts are triggered by external experiences, and information regarding them is conveyed to us by sensory inputs that have been gathered from our environment. Our conflicts therefore seem to us to take place externally, yet everything we understand about the meaning of what happened, and all our responses to the actions of others, are initiated and coordinated internally by the brains.

— Kenneth Cloke38

From the time that Mary walked past Ann in the corridor to the time Ann opened the door to enter the laboratory, less than a couple of seconds had passed. During that time, Ann interpreted the meaning of what had happened, made an assumption about that interpretation, reached a conclusion, checked how all this fitted in with her beliefs and decided what she was going to do about it. The more emotional a party becomes, the quicker they make their Journey of Inference and the more they believe that their inference is a true record of what happened.

Once the other party, such as Mary is this scenario, becomes aware of tension in the relationship, they start to make their own Journey of Inference. Each time one party acts, or omits to act, the other party to the conflict makes a further Journey of Inference. This in turn informs the actions that they take, and so the conflict becomes cyclical and escalates. As the conflict escalates, parties usually only observe the data that matches their previous beliefs and conclusions and bypass other observable data.

When parties in conflict act, they firmly believe that they are taking the correct action. Their positions then become more hardened and entrenched.

The concept of the “ladder of inference” was first developed by Chris Argyris and subsequently presented by Peter Senge in his book The Fifth Discipline.39 In this book I am calling it the “Journey of Inference” because I consider it to be a continuous circular journey in the mind rather than a journey to the top of a ladder and back down again.

Selecting data and making inferences is largely an unconscious process, but it can be made conscious through mediation questions. Supporting parties to be aware of the limited information from which they made their inferences and assumptions, and then reached their conclusions, is vital to the creation of mutual understanding. Journey of Inference questions facilitate the identification of what triggered a party’s reaction as well as their subsequent interpretations and the adoption of their positions.

When links are made between a party’s interpretations and their resultant actions, that can help to explain the rationale behind their behavior. Asking a party about how they perceived and interpreted an action by the other, and then comparing this with the actual intention of that party who took the action, also serves to bring new information and insight to a mediation process.

Journey of Inference questions support parties to look for new and clarifying information that may even prove their interpretations and assumptions to have been incorrect. The resulting reinterpretations they make may then be more accurate and balanced.

These questions are used:

✓ When there is a need to identify and explore the point in time when a party adopted their position about their conflict (conflict trigger), or when the conflict escalated

✓ When exploration of a party’s thought process would lead to greater understanding between parties

✓ When parties do not understand the behavior of the other party

✓ When parties are intransigent about their positions

✓ When a party states that they know exactly what the intentions of the other party were, and when you, as the mediator, have heard differently

Parties demonstrate this with statements such as:

I know exactly what she was trying to do …

Obviously, she did it because …

Well it is very clear to me that …

✓ When parties do not differentiate between their opinions and facts and put forward an opinion as being a fact

✓ When conflict has escalated and each party’s actions are influenced by what the other party said or did, leading to a circular conflict dynamic

✓ When facilitating a party’s expression of regret by asking questions about what they would have done differently if they had had the information and insight learned during the mediation discussion

While Chapter 4 contains generic guidelines for asking questions, additional specific guidelines for asking Journey of Inference questions are set out here.

✓ Journey of Inference questions should be asked only after the parties have told their story. To ask them before or during this initial storytelling may appear analytical and judgmental.

✓ Each party may be asked about his or her Journey of Inference from beginning to end:

or

✓ The parties may be asked in turn about their interpretations, then about their assumptions, and so on. But this latter method requires very tight facilitation.

✓ After a party’s response, and prior to asking the next question, a mediator sometimes needs to reflect back what they have heard so that the party does not feel like they are being interrogated.

✓ Parties may find it challenging to differentiate between interpretations and assumptions. One way to counteract this is to first ask, “What did you think that X meant?” when asking about interpretations, and then, “And what did you then think that would mean?” for assumptions.

✓ A party can be asked about his or her own Journey of Inference and then be asked to hypothesize about the other party’s Journey of Inference. This can be helpful in a joint meeting if one party claims that the other party does not understand them, but when you as the mediator know differently.

✓ The Journey of Inference questioning process can stop at any time, if necessary, for example:

■ If understanding is reached early in the questioning process — for instance, at interpretations stage.

■ If one party is finding the process too intense and difficult.

There are three steps involved in developing a series of Journey of Inference questions:

Step 1: Hearing the narrative of a party

Step 2: Challenging the narrative

Step 3: Building a possible new narrative

Questioning Tasks |

Stages of a Journey of Inference |

Step 1 Hearing the narrative of a party Exploring and focusing thinking for each of the stages of the Journey of Inference And Step 2 Challenging the narrative Connecting and expanding the thinking of a party about each stage of the Journey of Inference |

Stage 1: The consciously or unconsciously selected data Stage 2: The interpretations made from the data selected Stage 3: The assumptions formed because of the interpretations made Stage 4: The conclusions or judgments reached Stage 5: How the judgments and conclusions were informed by the beliefs of the party Stage 6: The decisions or actions taken because of the beliefs of the party about the situation |

|

|

Step 3 Building a possible new narrative Connecting and expanding thinking |

When the past has been deconstructed, and it appears, or is stated, that new learning and insight have been gained, it is time to start creating a new narrative with possibilities for agreement. A review of the process may be done intermittently, both during the Journey of Inference question flow and at the end of the process. |

S3: Seeking Information questions need to be asked about the Journey of Inference made by a party: what did they see, how did they interpret what they saw, what assumptions did they make, what conclusions did they reach, on what beliefs were their conclusions based, and what decisions or actions did they take? The goal during Step 1 is to uncover new information but not necessarily to create a paradigm shift, although one may result.

The case study of Ann and Mary is used for the flow of questions here. This example focuses only on Ann’s Journey of Inference, but in real practice Mary would be asked similar questions.

The Event

■ Ann, would you like to tell me what happened, please, when you and Mary passed each other in the corridor? Then what happened?

Selected Data

■ What did you observe, Ann? What information or facts did you take from this event?

Interpretations

■ When that happened [Mary walking past you with her head down], what did you think it meant? What brought you to this interpretation?

Assumptions

■ And what did you think that meant, and what assumptions did you make about what might happen? What brought you to that assumption?

Conclusions and Judgments

■ After you made that assumption, what conclusions or judgments did you come to? What brought you to this judgment or conclusion?

Beliefs

■ What are your beliefs about the world and how people usually behave in a situation like this?

Actions

■ How did these beliefs influence the decisions you made or the actions you took afterwards? What did you decide to do?

■ And then what happened? What else happened?

Selected Data

■ What had you been thinking/feeling about Mary before/when this happened?

■ On what did you base that thinking? What was the tangible evidence for this?

■ What had been your expectations of Mary? What influenced those expectations?

■ If you had not been concentrating on what you were expecting, what else might you have seen?

■ What would others have observed if they had been there when Mary walked past you with her head down?

■ When this happened, what did this trigger in you? What was going on for you inside?

■ And how could your sense of insecurity about the friendship have influenced what you saw/did not see?

■ What are the things you may have missed?

■ On a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 indicating complete certainty, how certain can you be about...?

■ What is this uncertainty about? (If the response is less than 10)

Interpretations

■ Ann, what did you think might have been Mary’s intention?

■ What influenced or contributed to you interpreting what you observed in this way?

■ How might your stated niggly feeling about your friendship with Mary have influenced what you actually saw and your interpretations? If your friendship had still been good when Mary passed you in the corridor with her head down, what might your interpretations have been?

■ What are all the questions you have been asking yourself since this happened?

■ Hypothetically, if you had made an interpretation opposite to the one you made, what may have been the result?

■ If you were to look at yourself and this incident from a balcony, what might you have seen and what interpretations might you have made?

■ If I was to ask you to prove yourself wrong, what evidence would there be to support this?

■ At this stage, on a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 indicating complete certainty, how certain are you of your initial interpretation?

■ Tell me about the bit of uncertainty that you mentioned. What is this uncertainty about?

■ Is there a time or a circumstance that might result in you interpreting this differently?

Questions can also be asked about the perspective of the other party:

■ If asked, what might Mary say about the time you saw her passing you in the hospital corridor?

■ What do you think would surprise Mary the most about what you interpreted from this situation, and about what you mentioned about her intent?

■ What interpretation might Mary have liked you to make?

If a mediator knows that Ann’s inferences about Mary were not in line with the stated intentions of Mary, then ask:

■ Ann, if you were to hear that Mary had not actually meant that in the way that you interpreted it, and if she were to say that she regretted what happened afterwards because she valued your friendship, how would that affect the way you interpret it?

At this stage there may be sufficient insight created with Ann and no need to continue, but if this is not the case, then continue asking questions about the rest of the stages of a Journey of Inference:

Assumptions

■ What assumptions did you make after you initially interpreted Mary’s actions in that way?

■ What did you think was going to happen?

■ What influenced you to make this specific assumption?

■ What other assumptions could you have made?

■ If you had made a different assumption, what might have been the outcome?

The mediator may continue with more questions about the assumptions made, based on Ann’s responses if relevant.

■ After you made that initial assumption, what judgment or conclusion did you come to, Ann?

■ What brought you to make this judgment or conclusion? What did this decision mean for you?

■ What other conclusions could you have come to?

■ If you were to try to persuade yourself that this conclusion was incorrect, how would you do this, and what evidence might there be to support this hypothetical conclusion?

■ What might have happened if you had come to different conclusions?

The mediator may continue with more questions about the conclusions made, and ask the party to rank their alternative conclusions, if relevant.

Beliefs

■ What is it you think or believe about life or people that brought you to that conclusion? How has this belief served you in the past? Are there situations where these beliefs may be valid or invalid? What are the distinctions you make between these situations?

■ What other beliefs do you have that could have resulted in your reaching a different conclusion?

■ Reflecting on the thoughts you have just expressed, if you had interpreted what you saw differently, and if you had reached a different conclusion, how would that have fitted in with your beliefs about the world and about how people usually behave in a situation like this?

■ What thoughts or reflections is this raising for you?

Actions

■ You mentioned earlier that after this event you made decisions about how you were going to respond to it and that the conflict escalated and you felt more entrenched. Having reflected on this now, what other decisions or actions could you have taken?

■ How might this have impacted on the conflict situation and its progression?

■ What might have been the outcomes?

At times, only one party needs to be asked Journey of Inference questions. But in this case, Mary had also made a Journey of Inference, so similar questions needed to be asked of her.

During this flow of questions, Mary said she had not even noticed Ann in the corridor that morning, but she had certainly noticed the mood that Ann was in when she entered the lab because other staff had noted it too (data selected).

Mary said she remembered this morning clearly as she and her husband had just had another huge row before she came to work that morning. Mary went on to say that things had not been good between herself and her husband recently, and she had slowly been coming to the realization over the last few months that her marriage was ending, but after that morning’s row, she said she became convinced that separation was the only answer.

Mary said she was upset by this bad humor of Ann’s even though she knew she had been engrossed in her own problems and had not been chatting to Ann as much as usual. But Mary said she did not think that Ann’s bad mood that morning had anything to do with her, as Ann displayed the same negative behavior toward all the other staff (interpretation). Because of this, Mary thought the problem would get sorted out by someone else in the end (assumption).

Mary said she remembered reflecting that this problem with Ann was coming on top of her marriage problems, and she did not have the energy to do anything but concentrate on her own marital problems (conclusion). Mary said that if she had not been so troubled already, she would have chatted with Ann to see what was wrong with her that morning, as she really felt it was important to be honest and talk about things face to face (belief). But she said she was too engrossed in her own marital worries at the time.

But Mary said that as time went on, she slowly started to surmise that maybe Ann did have a specific problem with her, and when Ann lost her temper with her in the hospital cafeteria this was confirmed — with a bang! Mary said that after that happened she went to the HR department to make a complaint against Ann, as she felt completely humiliated by Ann’s public display of temper toward her (action).

When the past has been deconstructed and it appears, or is stated, that new learning and insight have been gained by both parties, then it is time to start reflecting on any further misinterpretations that parties may have made.

■ Mary and Ann, as the conflict progressed, what do you think each of you may have intended that may have been misinterpreted by the other?

■ What do each of you think your misinterpretation may have meant for the other party?

■ In what way might this interpretation have led to either of you employing a particular behavior as a response?

Creating understanding between the parties is further helped by facilitating them to talk about the impact that the conflict is having on them. This may only be done if a mediator knows that each party will listen to the other respectfully.

■ How has this conflict impacted on both of you?

■ What has been the worst thing for each of you in all this?

■ How did the impact of all this influence the thinking of both of you and the actions you took?

■ With what kinds of things do you think the other party struggled?

■ What do each of you need the other person to know or understand now?

■ What might each of you have needed for this to happen differently?

■ What could each of you now offer the other?

If there has been a paradigm shift in one or both parties, then the following questions may allow for some regret to be shown and may open possibilities for solutions.

■ If you were to go back in time with the information that you have now, what might each of you have said/done differently?

■ If you were to tell this story now to another person, based on the understanding you have both gained, how would you describe this story to them?

■ If something like this were to happen again, how would you manage it? What would each of you need from the other? What could each of you offer the other?

■ What can be taken from your learning to inform agreements between you for the future?

At any stage of the Journey of Inference questioning process, parties can be asked about:

■ The process that is being used

■ Whether they have gained any new information or insight

■ The impact of this new information or insight on their thinking or approach

■ Whether, in retrospect, they would have done anything differently. This could facilitate some regret and help the parties to bring this learning into a future agreement.

Examples of questions:

■ What was it like for you to go through that thinking process?

■ Is there anything else that you may not have said that the other person does not know?

■ What have you not discussed that you might still need to talk about with each other?

■ What has changed for you because of this process?

■ What may have influenced or contributed to your change in thinking?

■ What might you now need from each other to continue this process?

■ What would you like to offer each other?