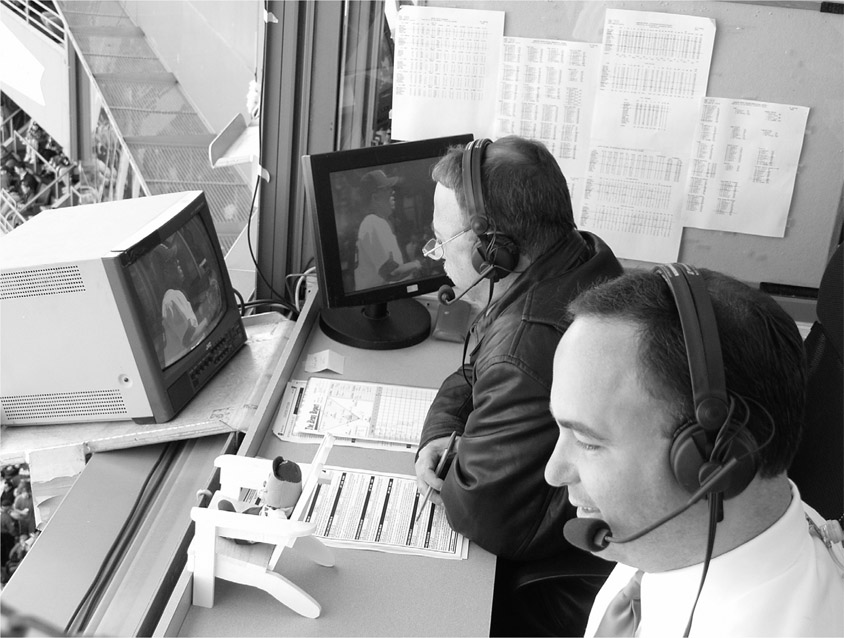

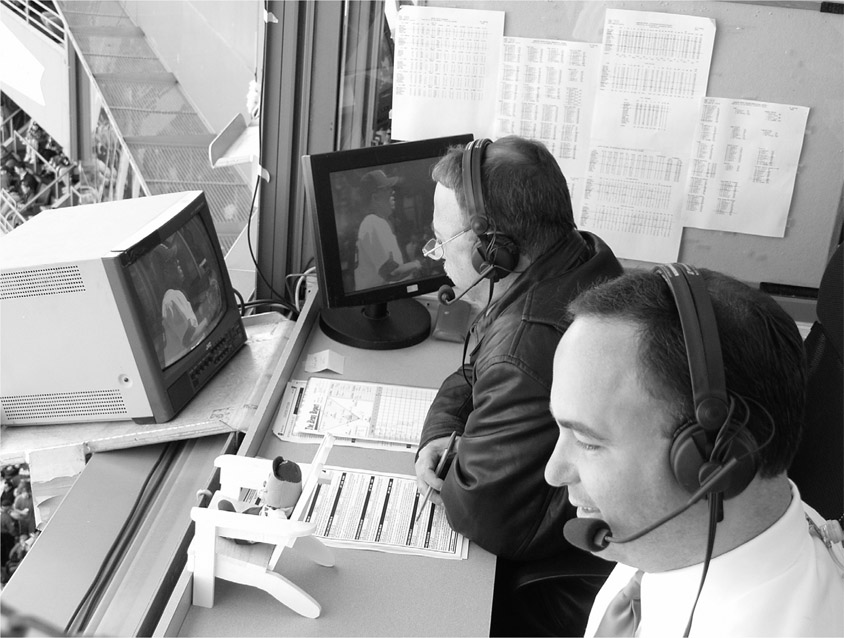

Men at work midgame in the broadcast booth. Don Orsillo calls the plays while I study the monitors for details and Wally keeps an eye on the wall.

Photo by Corey Sandler

C H A P T E R T H R E E

It takes just four-tenths of a second or so for a baseball to travel from the pitcher’s hand to the plate. In that time a good hitter tries to figure out what kind of pitch is coming, where it’s going, and whether it’s worth a swing.

One key to recognizing the pitch is to focus on the pitcher’s hand as it comes through to the release point. Attentive hitters also pay attention to the arm slot, which is the angle of the arm as the ball is released. A pitcher can have an over-the-top, three-quarter, sidearm, submarine, or any other arm slot.

When he throws a curveball, his arm may be more on top. When his wrist is facing home plate, the pitch is probably going to be something straight like a fastball. When the wrist is turned in a position like pulling down a shade, that’s going to be a breaking ball or a curve.

Pitching coaches try to encourage pitchers to have the same release point for every pitch, but that is a very difficult thing to do. There are so many tiny differences in the way the pitcher might throw the ball or release it. One sinker might drop more than the other. One splitter might break down and away, while the next pitch might be straight down.

A good slider is supposed to be hard, breaking down and away. If the pitcher changes his arm angle to drop more to the side, that slider is going to stay flat in the zone, and those go a long, long way when a batter makes contact with them.

If it’s a slider, the rotation of the ball is around the seams, and it looks like a dot coming at the hitter. A slider breaks the opposite direction from a curveball—from a left-handed pitcher that’s down and in to a right-handed hitter. A right-handed pitcher’s slider breaks down and in to a lefty at the plate.

When a pitcher throws a curve, the release is more over the top and the rotation of the spin is from twelve o’clock to six o’clock, as if it were tumbling toward the hitter. A right-handed pitcher’s curve breaks down and away from a righty at the plate; a left-handed pitcher’s curve moves in the opposite way.

There’s very little spin on a fastball, which comes in a straight line, although some pitchers’ fastballs rise or sink. With a changeup or splitter, hitters don’t see any flow to the rotation of the ball. Many players can pick up the lack of pattern pretty easily.

Hitters see the spin on a ball better in day games than at night. And some stadium lights are better than others.

Submarine pitchers who throw from the ground up are pretty rare in baseball, and that is one of the reasons some of them have success. ByungHyun Kim, who passed through Boston in 2003 and 2004, had uneven success; Mike Venafro had a similar career.

Batters are accustomed to pitchers throwing three-quarter, sidearm, or over the top, and all of a sudden there’s this guy scraping his knuckles against the mound. To hit a submariner the hitter has to look down toward the rubber instead of looking up high for the release point.

When submarine pitchers throw a sinker the ball darts down and away from a left-handed hitter and down and in to a right-handed hitter. And their breaking balls usually seem like Frisbees, like they are going uphill; if they don’t hit the right spot with it, the ball is going to go back the other direction a long way.

Dan Quisenberry was one of the best, a very good closer for Kansas City. He would bury the ball down and in on right-handed hitters.

My approach as a left-handed hitter was to try and hit him the other way because I figured most of the time the ball would be down and away. So I’d be leaning out over the plate and trying to make contact, and Quisenberry would bust a pitch inside because that was the last place I was looking for it.

Remy Says: Watch This

Pitching Mechanics

See if you can spot differences in the pitcher’s delivery. Does he use a different arm slot when he throws a curveball? If you’re sitting behind the plate—or watching on TV—can you see the spin on the ball?

The pitching rubber—the white rubber slab a pitcher must keep contact with as he starts his windup—is twenty-four inches wide. Watch where the pitcher plants his back foot; some start from the first-base side, some toward third, and some right in the middle.

The pitcher’s position on the rubber affects the angle of the ball coming in toward the plate. You’ll sometimes see a pitcher who has always thrown from the first-base side of the rubber move to the right side because the pitching coach has noticed something in his delivery or because he wants to show the hitter a different angle.

The fastball—the heat, cheese, smoke—is the basic pitch in baseball and the easiest to put in a particular location. A typical major league pitcher throws the fastball at about 90 miles per hour. Some reach the upper 90s and a few cross over 100 MPH on some pitches.

There are three different types of fastballs, and they vary by how the pitcher grips the seams.

The cross-seam fastball (or four-seam fastball ) is a straight pitch with very little movement. Thrown hard and flat, the ball rotates bottom to top, from six o’clock to twelve o’clock. When it is thrown hard, it almost looks as if it rises as it comes to home plate. Truth is, a rising fastball doesn’t jump up as it nears the plate. It’s just going uphill. You’ll see batters swinging underneath a rising fastball because a high pitch always looks better to hit than a low pitch.

The two-seam fastball is a sinking fastball, or a sinker, or a heavy fastball. Released the same way as a four-seam fastball and thrown just as hard, the wrist is turned just slightly. As a result the ball rotates off-center; it still spins bottom to top, but it might come in more like one o’clock to seven o’clock. It is also a little more difficult for the pitcher to hit a precise location in the strike zone with this pitch.

A two-seam fastball has good velocity—in the vicinity of 90 MPH for most pitchers—but it takes a hard dip at the end because of the rotation of the seams. If a batter makes contact, it feels like he’s hitting a shot put. This was Derek Lowe’s specialty, a ball that moves down and in to right-handers or down and away to a lefty.

And then there is the cutter or cut fastball, which is somewhere between a fastball and a slider. To throw a cut fastball, the pitcher holds it a little off-center from his normal grip. It looks like a fastball coming in, and at the last moment it cuts a little bit; thrown by a righty, it goes in on the hands of a left-handed hitter or toward the outside of the plate against a righty.

This is Mariano Rivera’s bread and butter. You would think that after batters see it a few times, they would be able to hit it, but most can’t. It is so deceptive.

A right-handed batter is likely to swing as a cut fastball moves away. With luck the batter hopes to at least be able to hit a cut fastball off the end of the bat, going to the opposite field. When he hits a ball off the end of the bat, he generally gets less power on the ball, and the bat often breaks.

Remy Says: Watch This

Eight Feet off the Ground

Another factor that comes into play is the height of the pitcher. As good as he was, Pedro Martínez is only of average height, about 5’11”. Curt Schilling and Josh Beckett each stand 6’5”. In 2007 the tallest pitcher for Boston was reliever and spot starter Kyle Snyder at 6’8”.

And then remember Randy Johnson at 6’10”. Standing on top of the mound, which is ten inches higher than home plate, and whipping his arm over his head, Johnson released the ball about 8 feet in the air.

Even the tallest batters were looking up at Johnson at an unusual angle. By the time he finished his stride, he might be just over 50 feet away from the batter. And oh, by the way, he’s a lefty and when he was right he threw the ball at something close to 98 miles per hour.

Or the hitter can hope the pitcher misses over the plate.

It’s just the opposite for a left-hander. When it cuts, it moves toward the label of the bat. He gets jammed and probably breaks the bat.

Either way, when a hitter faces a guy like Rivera, he had better have a good supply of bats.

Does he or doesn’t he? We’re not talking about whether Daisuke Matsuzaka colors his hair. The question is: Does he throw a gyroball? Or maybe, does such a pitch exist?

The answer, thus far, is a definite maybe.

It appears to me that among his wide arsenal of pitches there is one that may—sometimes—act a bit differently. I’m not convinced that it is a completely new pitch. I think it may be a slightly different spin on a slider or a cutter; some says it’s a tight screwball.

In any case it’s a hard-thrown breaking ball with late movement that moves down and away from a right-handed batter. It’s thrown so hard that you could also think of it as a fastball with movement.

Or maybe not.

A running fastball is almost like a cut fastball, but it is usually a mistake. The pitcher may have held the ball just a little bit off-center. The result is that at the last minute it runs in on a hitter.

Most cross-seam fastballs are thrown right over the top to three-quarters. And a lot of cut fastball pitchers are right over the top, too. Most sinker-ball pitchers release the ball down a little bit lower, still well above the shoulder.

A fastball is a good strikeout pitch for a pitcher who can get some velocity on the ball. There’s a baseball saying: “Climb the ladder.” The pitcher climbs the ladder with each successive pitch—throwing each pitch a little higher, at times out of the strike zone—hoping that the batter will chase as the ball goes upstairs.

A pitcher will sometimes throw what they call a batting practice fast-ball, sometimes when the count is 2-0. The batter is all geared up for the pitcher to throw something hard, and instead the pitcher will just take a little bit off his fastball and get the batter swinging out front a little bit.

The hook, the deuce, the hammer, the knee buckler, the yakker: whatever you call it, this is the basic breaking ball or curveball.

Instead of being released in a natural manner, in the direction the fingers point at the batter, a curveball is thrown with the wrist cocked so that the thumb is on top. When the ball is released, it rolls over the outside of the index finger. The ball rotates from top to bottom, the opposite of a fastball. A typical major leaguer’s curveball is about 7 to 10 miles per hour slower than his fastball.

A curveball thrown by a right-hander breaks down and away from a right-handed hitter, which makes it difficult to hit; a curve by the same pitcher will break down and in to a lefty, which is a location most batters prefer.

A curveball thrown by a left-handed pitcher breaks in the opposite way, which is tougher on a lefty at the plate and easier for a righty.

When a pitcher has a good breaking ball, you’ll see what I call a jelly leg curve. That happens when the pitcher throws the ball directly at the hitter and it curves back out over the plate. The hitter thinks he’s going to get hit, his legs buckle, and all of a sudden the ball is by him over the plate. That’s a nasty pitch.

A bad curve—hanging breaking ball—stays belt high and is often rede-posited over the fence by a power hitter.

The break of the pitch depends on arm angle. If the pitcher releases the ball straight over the top, the break is going to be twelve o’clock to six o’clock. If he drops down a little bit more to the side, it’s going to be two to eight. The basic definition of a curveball calls for it to start inside and finish away, but there are very effective pitchers like Mike Mussina, whose successful curves break almost straight down.

A right-handed pitcher can also throw a backdoor curve to a left-handed hitter. That’s a pitch that starts outside and breaks in to pick up the outside corner. Many lefties quit on that pitch because they expect it to be outside.

“[Satchel Paige] threw the ball as far from the bat and as close to the plate as possible.”

CASEY STENGEL

The screwball is a pitch we don’t see very often any more because it is so demanding on the arm and the elbow, and it is difficult to throw. It breaks in the opposite direction of the curve. It also doesn’t have the arc of a curve. A screwball from a right-hander goes into a righty at the plate and down and away from the left-hander.

A slider has a bigger break than the cut fastball but less than a curveball. It is thrown harder than a curveball, perhaps 4 or 5 miles per hour slower than a fastball. Today you see more sliders than curveballs, probably because it is an easier pitch to throw and control.

The pitcher holds his first two fingers close together, off-center, down the length of the seam on the ball. The late break in the pitch is caused by its off-center spin.

Sliders can be nasty because they look like a fastball out of the hand. Left-handers are generally good low-ball hitters, but if the slider arrives down and in off the plate, it is almost a blind spot.

If a pitcher makes a mistake with a slider, it goes a long way in the other direction. A slider has good velocity, and if the movement brings it out over the plate, the batter gets a good fastball-like swing on a pitch that is not thrown as hard.

To me the split-finger fastball or the splitter is the most difficult pitch to hit. It’s thrown like a fastball and the bottom just falls out. The pitcher is trying to get the batter to swing at a pitch that usually ends up out of the strike zone. He thinks he is swinging at a knee-high fastball and it is not there.

Remy’s Top Dawgs

Ever wonder what it’s like to face a tough pitcher? I played with Nolan Ryan on the Angels and then against him with the Red Sox. I saw him change more opposing lineups than any pitcher on a team I played on. If he was pitching, you would see guys ask for days off or report in with bad backs, the flu, a headache . . . whatever. Guys just didn’t want to face him.

When I was playing with him, every fastball was 99 or 100 miles per hour, and he had a hard curveball. As he matured in his career, he continued to intimidate but also learned how to pitch. He developed a changeup and turned the ball over now and then.

He had seven no-hitters; I can’t imagine that record ever being broken.

The grip for a splitter has the fingers spread very wide on the ball. A similar pitch is the forkball, but with the forkball the pitcher actually sticks the ball between his fingers. The splitter can be thrown harder. The result is a weird rotation that picks up some drag on the way to the plate, usually about 4 or 5 miles per hour slower than a fastball.

A good splitter goes down to drop out of the strike zone, but some may go down and in or down and away. When a pitcher has a good splitter going, he is going to keep his catcher real busy throughout the game, blocking a lot of balls on one hop. The pitcher needs to have confidence that his catcher can block a pitch when he throws it with a man on third base.

When I was playing, I thought this was the worst pitch ever invented; the only chance I had was when the pitcher made a mistake and it ended up belt high.

A good changeup—also known as an off-speed pitch, a dead fish, a circle change—is a very effective pitch. Done right, the arm action, the speed of the arm, and the angle of release are exactly the same as for a fastball.

The fastball is the fastest pitch; a slider is not quite as hard, but it is still moving. And a curveball is slower. But for most pitchers, the changeup is the slowest of all.

Hitting is timing, and batters generally gear themselves for fastballs. The changeup is designed to keep hitters off-balance with a pitch that looks like a fastball and has fastball movement but arrives at the plate just late enough to throw off their swing. And a smart pitcher makes it even more difficult by throwing an off-speed pitch on counts when batters think they are going to get a fastball.

The ideal changeup is low, about knee high or lower.

The pitcher holds the ball back in the palm of his hand and squeezes it tight, often with the thumb and forefinger touching in a “circle” on the side of the ball. While a fastball uses the full leverage of the arm to give it speed and picks up its spin from the first two fingers, the changeup grip spreads the force around more of the ball.

A good major league changeup may be 10 or 15 miles per hour slower than the same pitcher’s fastball, but it looks the same at the point of release. In theory a changeup is not as tough to hit as a splitter because it is off-speed and straight, while the splitter has that downward action. But for most batters, a changeup is a very tough pitch to hit.

When Pedro Martínez was king of the hill, he had a very effective changeup that acted almost like a screwball. He was the kind of pitcher who could walk up to home plate and tell the batter, “I am going to throw you three changeups and you won’t hit them.”

You would think that if a batter knew a changeup was coming, he could adjust his timing. But if a pitcher like Martínez throws a good one down and away, the batter may hit it, but not well.

There’s got to be a good spread between the fastball and the changeup to make the off-speed pitch effective. If Martínez is throwing the heat at 95 miles per hour, his changeup might be 78 MPH. That’s a pretty good ratio. If there’s a guy who’s throwing 87 miles per hour and his changeup is 83 MPH, that is not going to be good enough.

The knuckleball is not necessarily the most difficult to hit, but it is certainly the most unusual pitch a batter is ever going to see. It is a freak pitch, different from any other pitch. It’s slow—it can flutter in there as slow as 50 or 60 miles per hour—but there’s no predicting where it’ll go. Knuckleball pitchers themselves don’t always know.

I hope all Red Sox fans recognize the privilege we have in seeing Tim Wakefield throw the knuckler. He is among just a few of the great pitchers of modern baseball to be able to win with the pitch. I was going to say “master” the pitch, but I’m not sure that even Wakefield would use that word.

When Wakefield is having success, some of the best hitters in the game look like Little Leaguers swinging with their eyes closed at a curve ball. But when his knuckler flattens out, it sometimes looks like batting practice.

I’ve always wondered what a pitching coach can say to Wakefield when he starts to lose the ability to throw strikes or if the pitch stops knuckling. The ordinary bits of advice for a pitcher don’t apply.

But there is no arguing with success. As of the end of the 2007 season, Wakefield had 154 wins as a member of the Red Sox (plus 14 more from the beginning of his career with the Pittsburgh Pirates.) That puts him into second place on the all-time wins list for Boston, behind Cy Young and Roger Clemens who each recorded 192 wins for the Red Sox. (Mel Parnell is in fourth place with 123 wins, Luis Tiant won 122 games, and Pedro Martínez and Smoky Joe Wood are tied for sixth with 117 wins.)

To throw a knuckleball, the pitcher grips the ball with the tips of his first two fingers on top and the thumb anchoring it from below. The ball is pushed out toward the plate rather than thrown. (Contrary to what you might have thought, the knuckles are not involved in the pitch as it is thrown today; the name of the pitch comes from an old baseball term about the ball knuckling on the way to the plate.) A well-thrown knuckle-ball has no spin at all, and its movement on the way to the plate is affected by wind currents.

There have been a thousand theories on how to hit them: move up toward the pitcher, get closer to the plate, swing at the early pitches in the count because the pitcher is just trying to get one over for a strike. Or try to get hit by the pitch to get on base; it doesn’t hurt much.

There’s a baseball saying: If it’s high, let it fly. The theory is that if a knuckleball stays up high, that’s a good one to hit. If it is down low, it is probably going to dart all over the place. I’m not sure either theory works.

But knuckleball games can turn into disasters in a hurry if the pitcher loses control of the pitch and starts making wild pitches. Or the catcher may simply be unable to grab the ball or block it. Either way you’ve got guys running all over the bases.

And if the knuckleball stops knuckling—if it comes in flat—it goes back the other way a long distance. I have seen knuckleball pitchers start off great and all of a sudden the magic is gone. I have seen guys go through one inning when they can’t control the thing, and then they have a great one.

There’s not a lot a batter can do to prepare for a knuckler. Even if there’s someone who can throw a knuckleball in batting practice, many hitters say, “Why waste my time practicing against a pitch that is going to screw up my regular swing? I would rather take my normal batting practice against fastballs, feel good about my swing, and then take a chance in the game.”

Most pitchers would love to have the wind behind them; it helps their pitches move around and it bothers hitters to have the wind in their face. Knuckleballers want the wind against them because it seems to make the ball dance more. But for some reason Boston’s Wakefield has always seemed to do well in indoor stadiums, where there is no wind current to play with the ball as it comes in.

For most knuckleball pitchers their fastball becomes very effective when they throw it at a time when the batter is expecting a slow knuckler. Just like a change-up from a guy who throws heat, a change from a knuckleball to a fastball throws off the hitter’s timing.

A knuckleball pitcher may have a very ordinary fastball, maybe 80 MPH, but it can look like it is coming in at 90 MPH if the batter is looking for the knuckler.

If a knuckleball pitcher gets into a 2–0 or 3–0 count and he worries he might walk someone, he might sneak in a curveball or a fastball to try to get a strike. As a batter, that may be the last thing you’re expecting. So the fastball and the curveball become his trick pitches.

Years ago, we used to hear about pitchers who threw spitballs or Vaseline balls or who cut the ball in some way; you don’t hear much about that anymore. I am sure that still goes on, though. If a pitcher is throwing a fastball that is doctored with a foreign substance, the batter sees a different rotation, maybe one similar to that of a splitter. If the pitcher cuts into the hide, that may make the ball sail or make it dart away, depending on where the cut is. I don’t think the pitcher knows where it is going to go, but he knows it is going to do something different.

Of course, if a pitcher is caught doctoring the ball, he is gone from the game and probably due for a visit to the league office. But some guys are pretty crafty at their trade.

Sometimes a pitcher may just get lucky and receive a baseball with a cut in it from the last play. He’d be crazy to ask the umpire for a fresh ball. That’s why when a batter hits a foul ball that bounces around a bit, the umpire will take it out of play because there could be a cut on it. Or the batter might ask the ump to check it.

Is doctoring rampant? No. Are there certain guys who I think do it consistently? Yes. There always will be players trying to gain the advantage in some way.

Pitchers who throw illegal pitches can really mess with the mind of a hitter. He’ll keep stepping out and asking the umpire to check the ball and end up psyching himself out.

Joe Niekro had a file fall out of his back pocket on the mound. There are guys who have had tacks in their gloves. Some have had stuff sewn into their glove. In 1999 Brian Moehler, pitching for Detroit at the time, got caught with a small piece of sandpaper taped to his thumb and was suspended for a few starts.

I don’t know if it is true or not, but they used to say that Gaylord Perry would soak himself in baby oil prior to a game; when he started to sweat, he could get oil anywhere he wanted. Toward the end of his career, he used to throw a puffball; he would take the rosin bag and get a bunch of it in his hand, and when he threw the ball, it would seem to explode out of a cloud of rosin.

He didn’t mind being accused of all that stuff. The more he got batters thinking about it, the more it was to his advantage. He wanted them to think he was going to do something crazy.

I’m not making this stuff up, you know; Perry even wrote an autobiography about his life . . . and oils.