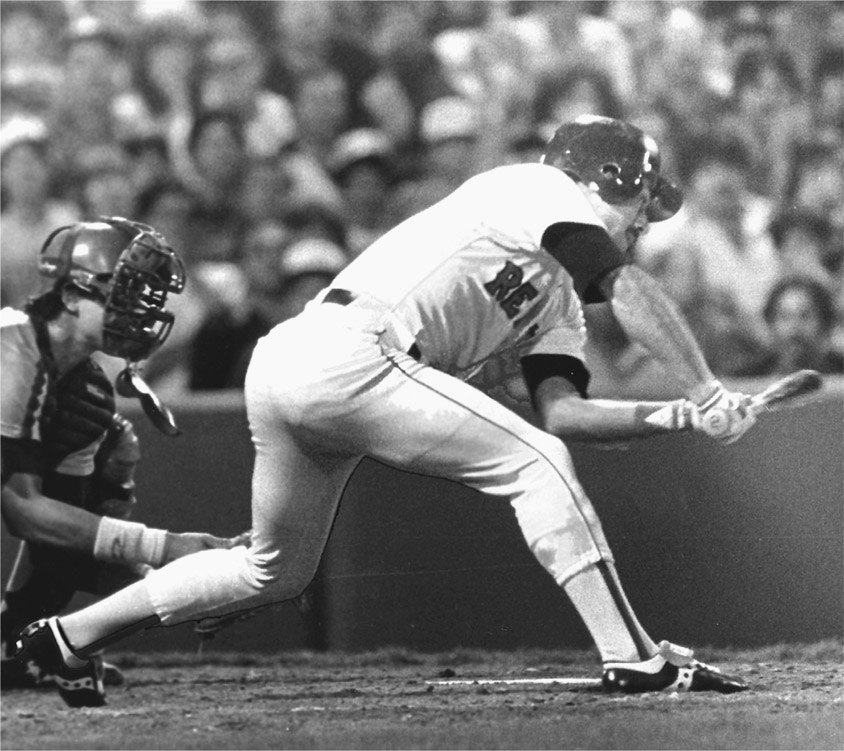

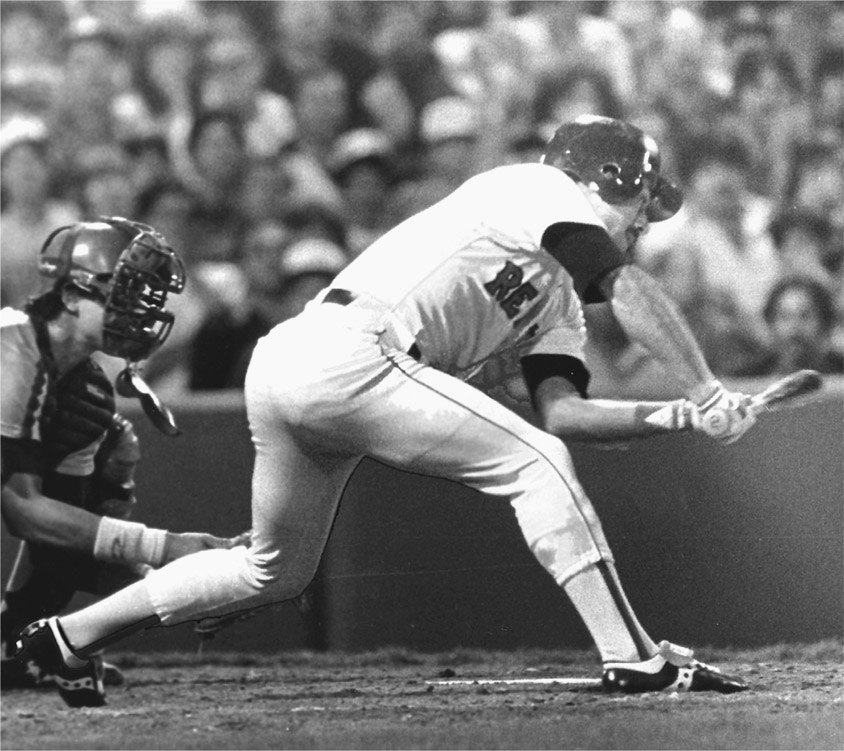

Checking my swing on a lunge for a bad pitch.

Photo courtesy Boston Red Sox

C H A P T E R F O U R

Pitchers have to be able to throw to the inside part of the plate. If that is taken away, hitters will lean out over the plate to hit nasty pitches on the outside corner.

A pitcher who doesn’t have the ability to work inside or is afraid to do it is not going to have great success.

One of the keys to pitching is intimidation of the batter; if the batter is not a little nervous at the plate, the pitcher has not done his job. A great pitcher wants batters to be worrying: Is this next pitch going to be inside or away?

Many of the great power pitchers achieved their success by establishing the inside of the plate; if they can make the batter move back a bit, that allows them to paint the outside corner with pitches that are harder to hit or harder to drive with power.

You can start with some of the all-time greats: Nolan Ryan and Roger Clemens among them. In today’s game some of the pitchers who owe at least some of their success to throwing inside include Justin Verlander of Detroit and Boston’s own Josh Beckett.

At the same time batters seem to be getting more and more upset about pitches inside: jamming, handcuffs, brushbacks, whatever you call them. Today it is almost to the point where anytime a pitcher throws inside, he gets at least a hard stare from the batter, and sometimes more.

It’s absurd because that’s the way the game is supposed to be played. If a pitcher is going to pitch inside, occasionally batters are going to get hit; that doesn’t mean it was intentional. If a batter gets hit because the pitcher is working inside, he should be happy to get on base.

The use of aluminum bats in high school and college may be one reason why some pitchers are reluctant to throw inside, and why some batters coming into professional baseball are not used to seeing pitches in on their fists. With an aluminum bat, many batters can still hit the ball well if they’re jammed, and an aluminum bat is not going to break with a swing on an inside pitch.

Another reason pitchers can’t claim to own the inside of the plate is the body armor that some batters now wear. They’ve got all this junk on and they are not afraid to get hit.

There are, of course, situations in which some pitchers will purposely throw at a batter; often it is in retaliation for something done to a player on their team. Sometimes, though, a batter gets hit because the pitcher loses command of a pitch. The batter, the fans, and the umpire have to know the situation.

Players used to police themselves; a pitcher who hit a batter knew that a guy on his side was likely to get plunked later in the game. Or in the National League, the pitcher himself would have to come up to bat sooner or later.

But now umpires have been instructed by Major League Baseball to get more involved. Today any time an umpire believes a pitcher has intentionally thrown at a batter, he can immediately eject the pitcher. Or he can warn both managers that the next time either side hits a batter or even comes close, the pitcher and the manager will be out of the game.

Look, I’m not saying that pitchers should be throwing at guy’s heads. That is dangerous.

But when he was at his peak, many managers were quite happy to see a pitcher like Pedro Martínez issued a warning by the umpire against throwing inside.

The fact is that a pitcher like Martínez doesn’t care about warnings; he still has the control to be able to pitch inside. At this point we’ve got to trust the umpire. He has to have a knowledge of what’s going on in the game. Is this guy trying to hit somebody, or is he just pitching inside?

A warning to Martínez or Clemens made no difference. They were not going to stop throwing inside. That’s why Martínez and perhaps Clemens are going to go to the Hall of Fame.

The Rem Dawg Remembers

I’m Coming In

Batters coming to the plate against Roger Clemens or Pedro Martínez at their peak never got too comfortable in the box.

Just before the 2003 All-Star Game, the Red Sox came into Yankee Stadium with their bats blazing, bashing David Wells and Clemens in back-to-back games. Clemens hit Kevin Millar with a high-and-inside pitch—perhaps because the Sox had hit seven home runs the day before, or maybe just because he wanted to establish his ownership of the inside of the plate.

Millar was angry, but it was Clemens who was upset. “Guys don’t get out of the way anymore,” Clemens told reporters after the loss. “If you’re throwing a ball 85 or 88, you’ve got a chance. But I rush it. When I’m coming in, I’m coming in hard.”

Former Boston dirt dog Trot Nixon had a great response, depositing Clemens’s next pitch over the fence. And David Ortiz hit two more out.

All that said, when Clemens faced Martínez in Game 3 of the ALCS in 2003, Pedro did not cover himself in glory in the third inning with his pitching to Karim García and his taunts to Yankee catcher Jorge Posada.

And then the next inning, when Manny Ramírez overreacted to a high pitch from Clemens, the benches cleared and out came Yankees coach Don Zimmer, charging at Martínez. Here was a seventy-two-year-old guy still thinking like a twenty-year-old. But Zim’s a baseball lifer. He forgets sometimes, and his competitiveness takes over.

Baseball lore includes stories about a pitcher announcing to the batter that he’s going to throw a fastball, daring him to hit it. It’s not all fiction.

I remember an episode between Bernie Williams of the Yankees and Pedro Martínez on the Red Sox. Bernie had this thing where he would step out of the box and just stand there; it drove Pedro crazy. And so Martínez starts yelling at Bernie, “Let’s go.”

In that situation everyone knew he was coming with his fastball because he was angry. Pedro did throw a fastball, and of course, he struck Williams out.

There have also been situations where great players are up for their final at bat in the big leagues, and the catcher will tell them—as a sign of respect for a player headed to the Hall of Fame—“Here comes a fast-ball.” I think that happened to Yastrzemski. But the problem was that the pitcher threw it a little too soft, and Yaz popped it up in his last at bat.

There are some top-notch pitchers who feel they are giving in to a hitter if they are asked to issue an intentional walk. The great pitchers are hungry for a test; that’s why they are great pitchers. They have the ability and they don’t feel there is anybody in the world who can hit them. They have no fear of an awesome matchup.

I remember one game when the manager came out and told Nolan Ryan to walk the next batter, and he said, “No.” Ryan told the catcher to get back behind the plate, and then he struck out the batter. He was a superstar player and he was not going to be embarrassed by issuing a walk to this guy. It was: “I am Nolan Ryan, and you are who you are, and I am going to get you out.”

And what do you think the manager had to say about it? Something like: “Nice going, Nolan.” What else was he going to say to him?

But most pitchers go along with the program. If the manager puts up four fingers—the signal for an intentional walk—they’re okay with it. They know the manager is trying to set up a double play, or pitch around a really tough hitter.

And of course there was the 2002 World Series during which Barry Bonds was walked nearly every time he came up to bat in a meaningful situation. In all the time that I have been in baseball, I have never seen anything like that. For the record he was walked thirteen times in seven games. He still managed to hit four home runs, but it was the Angels who won the Series. And in 2003 Bonds was given six more intentional walks and the Giants fell to the Florida Marlins in the divisional series.

There are obvious situations when a pitcher should walk a great hitter, places where a walk will hurt a lot less than a hit. But I had never seen the game being played around one player. Actually, I don’t blame the manager, Mike Scioscia; I would have done the same thing. But as a pure baseball fan I would have loved to see Bonds swing the bat; he is one of the greatest home-run hitters of all time.

In 1998 Buck Showalter of the Arizona Diamondbacks ordered Bonds walked with the bases loaded; the D-Backs had an 8–6 lead, and they walked him to make it 8–7 to get to the next guy. It worked; the D-Backs won the game.

In July of 2007, just before the All-Star break, the Red Sox were facing the Detroit Tigers in a tight game. David Ortiz started off the game with a two-run homer, and Manny Ramírez was scuffling. And so, Detroit’s wily manager Jim Leyland had slugger Big Papi intentionally walked three times, and Ortiz earned a fourth free pass on his own. Oh, and the Tigers won the game 3–2 in the bottom of the thirteenth inning.

Not all intentional walks are as obvious as the catcher standing up and moving outside of the batter’s box to receive four pitches. Sometimes the way it works is that the pitcher is instructed to throw nothing hittable; if the batter chases a bad pitch, that’s fine because he’s likely to pop it up or hit it weakly. But if the batter refuses to swing at bad stuff, so be it. Let him walk instead of putting the ball over the fence. The manager is saying: It wouldn’t kill us if we walked him, but let’s see if he will swing at something bad. We call that a pitch-around.

In the 2007 postseason, Boston’s two big boppers, David Ortiz and Manny Ramírez, received fourteen and sixteen walks respectively over fourteen games. Only a handful were intentional, but you can bet that most of the others were the result of a pitcher and manager saying, “I’m not going to let you beat us with one swing.” Of course, there was also Mike Lowell and five or six other good bats in the lineup and the Red Sox got the flashy rings once again.

Good hitters know when pitchers are doing that, and don’t get fooled. On the other hand, an impatient hitter might be tricked into swinging. He is not a disciplined hitter, or he may be young and inexperienced.