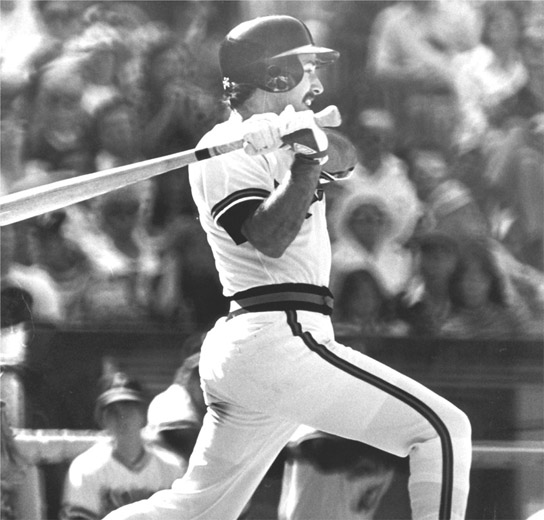

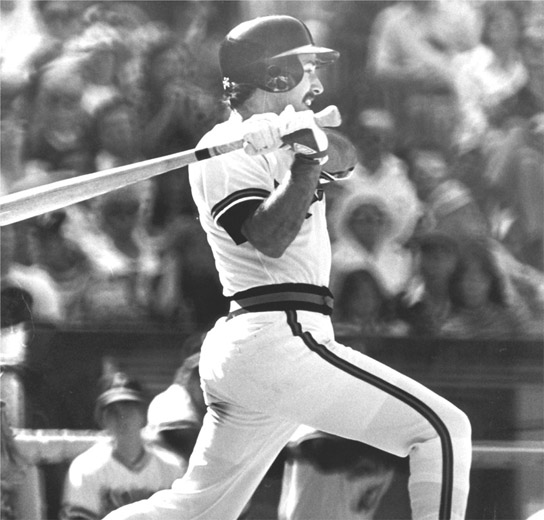

Not a particularly good follow-through, probably a swing that resulted in a weak ground ball or a soft fly to the opposite field. When I got to Boston, Walt Hriniak changed my swing more downward to get the ball on the ground and on the line.

Photo courtesy Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim Baseball Club

C H A P T E R F I V E

The primary skill in baseball is hitting. That’s the toughest thing in baseball, and it may be the most difficult thing to do in any sport. Every player who goes to the plate wants to hit. Great defensive players take pride in their fielding, but even they want to go up and hit. That’s the fun of the game.

Over the history of organized baseball, a .300 batting average has always been the mark of a good hitter. It hasn’t changed all that much over the years; I guess that has to do with the skills of the guy throwing the ball and also the fact that there are eight other players out there trying to get the batter out.

Now consider someone hitting .406, like Ted Williams did for the Red Sox in 1941. That’s an incredible number. That’s why he always had the great respect of players, because they know how difficult that is to do: a little better than 2 for 5 across an entire season.

One of the most telling things about baseball is that a superstar batting .300 is someone who fails to get a hit at least seven out of ten times to the plate.

Over the history of modern baseball, team batting averages have remained pretty consistent: A successful team usually bats somewhere in the range of .260 to .280. Let’s take a look at a few notable years in Boston Red Sox history.

|

Year |

Red Sox batting avg. |

Comments |

|

1918 |

.249 |

First place . . . and winner of the World Series. |

|

1941 |

.283 |

Ted Williams batted .406 all by himself, but Boston finished seventeen games behind the Yankees. |

|

1950 |

.302 |

The team batting average record, but the Red Sox ended four games behind the Yankees. |

|

1967 |

.255 |

The “Impossible Dream” included a ticket to the World Series but no ring. |

|

1975 |

.275 |

Another trip to the World Series, but still no ring. |

|

1978 |

.267 |

My first year with the Red Sox; I batted .278, went to the All-Star Game, and Boston finished one game behind the Yankees. |

|

1986 |

.271 |

First place, five and one-half games above the Yankees. Second place in the World Series, losing to the Mets in seven games. |

|

1993–2003 |

.275 |

The team batting average during a decade of chasing the Yankees. |

|

2003 |

.289 |

A record-breaking offense included the highest slugging percentage in MLB history, but only good enough for second place, six games behind the Yankees. |

|

2004 |

.282 |

222 home runs, including 43 from Ramirez and 41 from Ortiz, good enough for second place to the Yankees once again. But once October was over, the World Series Championship flag would fly over Fenway Park for the first time since 1918. |

|

2005 |

.281 |

The highest team batting average in the major leagues. The Red Sox also had the highest number of runs scored and RBIs in all of baseball. The Sox won ninety-five games, same as the Yankees, but they did not win the division title because New York won one more game in the series between the teams. Neither Boston nor the Yankees advanced past the divisional series in postseason. |

|

2006 |

.269 |

192 home runs (including 54 by David Ortiz) but only 86 wins to finish a dismal third in the standings behind Toronto and the Yankees. |

|

2007 |

.279 |

The Red Sox had fewer hits and home runs (only 166) than the previous year. But solid hitting and very strong pitching allowed Boston to win 96 games, which was worth a two-game lead over the Yankees and sole possession of first place in the American League East. Oh, and they won their second World Series in four seasons. |

When I played, the great hitters were batting .320 or .330. Now they are hitting .360 or .370. Why? I’d start with better training. There are smaller ballparks. And great pitching is spread pretty thin.

At the same time that the averages of the better batters have inched up slightly, there continue to be players who reside at or near the “Mendoza Line.” (Mario Mendoza, a pretty good defensive shortstop for the Pirates, Mariners, and Rangers from 1974 to 1982, batted as low as .180 for a season and ended up with a career batting average of .215. Many sportscasters, writers, and fans look to see who is at or below .200, which has become known as the Mendoza Line.)

It doesn’t take that many hits to improve a so-so average to a notable one. Calculating a batting average over the course of a season with 500 at bats, the difference between batting .290 and .310 is just ten hits:one more hit every sixteen games.

I was a pretty good bunter, and coaches used to tell me all the time that if I got twenty-five extra bunt hits a year, I would hit forty points higher.

If I had a couple of hits and went 2 for 5, I figured I had done pretty well. If I was 1 for 4, I figured I had survived. Players hope the occasional 2 for 2s and 3 for 3s will keep them afloat.

Being a hitting coach is not an easy job. The coach may have a philosophy, but he’s the coach for fifteen position players, and they all have different hitting styles. Anyway, players have a tendency to go to anyone they think can help them, whether it is the coach or the clubhouse guy.

Some hitting coaches say their goal is to have every player come to the plate with a plan. That means knowing the opposing pitcher, knowing how he pitches to you, and knowing how he adjusts with men in scoring position. And it means learning how to work the count to increase your chances of getting a pitch you can hit.

One common goal is to try to get to a hitter’s count. The problem, though, is that many players get in a hitter’s count, let’s say 2–0, and then fail to swing at their pitch.

Even with a plan there are players who are very set in their ways and well known for their habits. There are some batters who almost always swing at the first pitch. If pitchers know someone is a first-pitch hitter, they’ll usually try not to throw something hittable to open the at bat.

That’s not to say that there haven’t been a lot of great first-ball hitters in the history of this game: Paul Molitor, Kirby Puckett, and Nomar Garciaparra among them. Everybody in the world knew they were going to swing at the first pitch if it was a strike. But the big difference: If it wasn’t a strike, they would let it go.

At the other end of the spectrum, you have some batters who never swing at the first pitch, preferring to get some sense of the pattern and speed of the pitches. In his rookie season of 2007, Dustin Pedroia took the first pitch 84.8 percent of the time.

And Manny Ramírez has gone entire seasons without swinging at a 3–0 pitch; some coach somewhere must have drilled that into him. It hurts sometimes to see a pitcher lay one right down the middle of the plate on that count and watch Manny take it.

On many teams today it all comes down to an increased emphasis on boosting a batter’s on-base percentage. Let me define that: On-base percentage is a recalculated batting average that includes hits, walks, and times hit by a pitch. It gives a better sense of how often a player gets on base and sets up a chance for a run.

A batter, with the assistance of the hitting coach, makes a plan based on his past history with a pitcher. It is much easier today because of videotape and computers. Most teams have a library of at bats, pitches, and plays that can be consulted before, during, and after the game.

Before the game, or at least at the start of a series, most teams will have a hitter’s meeting, led by the hitting coach. They will go over the starting pitchers and the bull pen. For each pitcher they want to know the velocity of his pitches. Does his ball sink or is it straight? What are his off-speed pitches? Does he throw a curveball, a slider, or both? What is his changeup? Does it run away from right-handers? Does he throw a split-finger fastball? What is his percentage of first-pitch strikes? Does this guy start everybody off with a breaking ball?

There are some pitchers who won’t throw fastballs when they are behind in the count: 1–0, 2–0, 3–0, and 3–1. Instead they will throw a breaking ball.

“I’m impressed with this kid. He really swings a bat. A left-handed hitter who hits to the opposite field as he does is going to help himself at Fenway Park. Some of those opposite-field fly balls will reach the screen or at least be off the wall.”

TED WILLIAMS, SPEAKING ABOUT JERRY REMY IN HIS FIRST SPRING TRAINING SEASON WITH THE RED SOX IN 1978. OF REMY’S SEVEN CAREER HOME RUNS, NONE CAME AT FENWAY PARK.

If there’s an unknown pitcher on the mound—a rookie or someone who just came over from the other league—when the leadoff hitter gets back to the dugout, many of the guys will go up to him and ask, “What’s he got?” But that doesn’t always tell you much because a good pitcher throws differently to each batter. A pitcher would attack me differently than he would attack hitters behind me.

A player might go up to bat a couple of times when the pitcher has nothing on his fastball. On the third at bat, all of a sudden it’s really moving. Or a pitcher might have been getting the curve over early in the game and then lost it in the sixth inning.

These are the sorts of things that will spread around quickly on the bench.

But when you are hitting well, you don’t think about any of this. It’s when you’re not swinging well that most of this stuff comes into play, and there are times when you think way too much.

There’s a baseball saying that goes like this: When you’re hitting well, the ball looks like a beach ball, and when you’re not hitting well, it looks like a golf ball.

Curt Schilling is an extraordinary athlete, but he has some pretty ordinary superstitions and rituals. He won’t step on the foul line when walking to or from the pitching mound. For your basic 7:05 p.m. night game, he starts his warm-up routine at 6:45 p.m., not 6:44 and not 6:46. And he kisses his necklace before throwing the first pitch.

Old favorite Nomar Garciaparra used to drive some people nuts with his apparent inability to find batting gloves that fit. Garciaparra who, when he was at his peak, was one of the best hitters in baseball, tugged on his batting gloves over and over, tapped his helmet, and kicked his feet before he settled in for a pitch. If he didn’t get a pitch to hit, he’d do it all over again before the next pitch. You have to wonder if he is going to have to medicate himself for obsessive-compulsive disorder when he is out of the game.

Watch the players run on and off the field: How many won’t step on the foul line, touch a bag, or take a particular route to the dugout?

If you went to every game and you focused on one player, you would see that he does the same things over and over again through spring training and 162 games a year. Players get into a routine and find a set way of doing things that works for them. Sometimes they get to a point that if they forget to do something, it throws them way out of whack.

At least Nomar went through his routine quickly. Manny Ramírez used to walk all over the place before he got in the box; he’s cut down on that now.

If the batter takes way too long, the umpire might say, “Let’s get going here.” The catcher, though, is not likely to squawk too much because he probably has his own routine when he comes up to bat.

If you get to the park early enough, go to your seats and watch batting practice. There’s a lot more to it than a couple of swings at easy tosses from a coach.

A good hitter has a plan for every batting practice. First might be a couple bunts. Then, he might try moving the ball to the opposite field, up the middle, and attempt to pull some balls.

A batter with a plan may work on hitting situations. He may begin with a hit-and-run swing, when he has to make contact because the runner on first is going to take off. Next, he’ll try to hit the ball to the right side to move a man over from second to third. Then, he’ll try to loft a fly ball to get a runner in from third.

Some players are very finicky about batting practice. The batting practice pitcher gets to know the spots where these guys want the ball. Some hitters call their own at bats, telling the pitcher to give them something down the middle of the plate, outside, or inside, so they can work on particular swings.

While all of this is going on, you’ll see infielders taking ground balls, working on their throws to first, and practicing double plays.

Outfielders may have a coach hitting fly balls to help them with their timing. If you are in a ballpark with some unusual features, you’ll probably see a coach working on that; at Fenway Park with the Green Monster, you’ll see coaches hitting balls off the wall so that left fielders can practice playing the rebound.

During batting practice you’ll usually see pitchers shagging fly balls in the outfield, and then they do whatever running program the pitching coach asks.

When some hitters come to a park like Fenway with the Green Monster in left or Yankee Stadium with the short porch in right, they feel compelled to make adjustments to their swings to try to take advantage of the park.

When you watch batting practice in New York, you’ll see some left-handed power hitters trying to hit one up on the second deck. When right-handers come to Fenway, you’ll see great shows during BP, with power hitters parking one after another on Lansdowne Street behind the Green Monster. That may not be the proper way to take batting practice, but some players can’t help themselves. They put on a show, and fans love to see it, but they may also be taking themselves out of their normal routine, possibly putting themselves off their game.

Let’s say that there are two different kinds of hitters—those who have their hands inside the ball and those who surround the ball.

When I say a hitter has his hands inside the ball, I mean that his hands are coming in closer to his body, and the barrel of the bat is pulled through the swing. This type of hitter is able to use the whole field.

A good example of this kind of player is Manny Ramírez, a power hitter who keeps his hands inside the ball and doesn’t surround it. The same thing goes for Barry Bonds. Wade Boggs, another great hitter, was like that, too. A-Rod has his hands inside the ball and has great power to all fields. He’s a bit like Ramírez with his leg kick and his smooth, controlled swing.

In general, though, a big power hitter surrounds the ball with his swing. By surrounding, I mean that instead of the hands starting in close to the hitter’s body, the hands are held out and away before the swing. A ball thrown inside can jam him; a batter who has his hands inside the ball gets to foul off the pitch.

Remy’s Top Dawgs

Ichiro Suzuki does things I have never seen before. He has the ability to hit any pitch in any part of the strike zone—and out of the strike zone—and hit it hard. I’ve seen him take two steps toward the pitcher, swing at a ball down near his shin, and foul it off the other way. I sit there and say, “How can he do that?”

In 2004 he broke George Sisler’s eighty-four-year-old record by collecting 262 hits in a single season. And he is also a very good outfielder with a strong arm.

In the 2007 All-Star Game, Ichiro put the American League ahead with an inside-the-park home run that skipped away from Ken Griffey Jr.

(You can thank Ichiro, and All-Star Game’s winning pitcher Josh Beck-ett, for giving Boston the home-field advantage in the World Series in 2007, although the Sox didn’t need to go past four games.)

Guys who surround the ball break a lot of bats because they get jammed, and they usually don’t have a high batting average, although they may hit more home runs.

From the pitcher’s point of view, a guy who surrounds the ball usually has more holes they can throw to. In a bases-loaded situation, I think most pitchers would rather have a power hitter up there. If he has some weaknesses they can exploit, they’ve got a chance to strike him out.

A contact hitter is a bigger problem for pitchers in a tough situation because he is going to put the ball into play. When he makes contact, something is going to happen—it could be a hit, an error, or an out that will drive in a run.

There are some players who are excellent at hitting bad balls: pitches out of the strike zone or strikes that most other hitters would not swing at unless they were in a two-strike count. A lot of these good bad-ball hitters keep their hands inside the ball.

When a pitcher with an above-average fastball throws that ball around the letters or higher, very few batters can hit the ball. Those few good high-ball hitters may be able to make contact, but you don’t see many high fastballs hit for home runs.

For most batters a high fastball is a pitch to stay away from. If it’s a high, hanging breaking ball, that’s a different story. Those are the ones that can go a long way in the other direction.

It used to be that left-handed hitters were considered low-ball hitters, while right-handed hitters were better at high pitches. That’s no longer necessarily true; all pitchers now work low, and most batters try (not always successfully) to not swing at a pitch above the belt unless it is a high breaking ball.

To hit a high pitch, you have to be able to get on top of it. One way to do that is to bring your hands up and in. Most players hold the bat higher. The swing is like chopping down a tree.

There are some batters who regularly have long at bats, fouling off pitch after pitch. You’ll hear some announcers and coaches say they are intentionally fouling off the pitch.

I can’t say that I have ever run into a player who has said, “I purposely fouled that off.” The reaction time for an incoming pitch is less than half a second, and we’re expecting a batter to decide whether to take a pitch, swing for a hit, or foul it off?

Does it look like guys do that? Yes, with extraordinary hitters like Ichiro Suzuki or Wade Boggs. You may see a guy like Ichiro foul off ten pitches. But I don’t think that Ichiro is saying to himself, “I am just going to flick at this one and foul it off.”

Most of these superior batters are contact hitters, hands-inside-the-baseball hitters who don’t strike out a lot. They swing and try to get the ball in play and get a hit. The best hitters can see a tough pitch and make contact, when most others would miss it. Such a hitter is spoiling a great pitch by making contact and not striking out.

Because of the angle of the bat, the location of the pitch, and his own hand–eye coordination, an exceptional hitter is able to foul that ball off and stay alive instead of swinging and missing it. He is able to get to pitches other guys can’t get to.

And I thought that one of the best performances of the 2007 regular season was Dustin Pedroia’s epic at bat against Eric Gagné (then with the Texas Rangers) on May 27. With a one-run lead going into the top of the ninth, Pedroia got to a 2–2 count and then fouled off seven consecutive pitches before finding one that he liked: a fastball over the heart of the plate that he drove 368 feet to left for a home run. It turned out to be the winning run, too, because the Rangers got one back in the bottom of the inning.

One judgment call for the umpire is whether a batter has checked his swing: started to swing and then changed his mind.

At what point has the swing become a strike? I look at it as mostly a judgment about whether the batter had control of the head of the bat. If it looks like the batter had control, I say it wasn’t a swing. Some people say it’s a strike when a batter “breaks his wrists.” To me that’s the same thing as losing control of the head of the bat. When a batter does that, his wrists roll over.

It is much easier for a batter who gets his hands inside the baseball to check his swing than it is for a guy who surrounds the ball. It is very hard for power hitters to check because they get so much whip into their swing. I once saw Jim Rice check his swing and have the bat snap right in his hands—that’s how strong he was.

It used to be that certain batters would choke up on the bat—move their hands up a bit from the handle toward the barrel—to get a little more control and a quicker swing. Some batters would choke up when they had two strikes against them and they just wanted to make contact, at the cost of some power.

Barry Bonds, who had tremendous power, choked up on the bat and still put balls out of the park.

What makes a great home-run hitter? Physically, he has to be big and strong—you don’t see many 5’9”, 165-pound home-run hitters—but, more than size, it comes down to bat speed and the pitches he chooses to swing at.

It is amazing how much fear players like Bonds put in the opposition. Players like him have the ability to change the complexion of the game with one swing.

Mark McGwire had that amazing home-run stare. He was a huge man with a slight uppercut swing, and he hit very high, very long monster home runs. When he made solid contact, you’d think: “Forget about it. Where’s this thing going?”

And we’ve all seen old movies of Babe Ruth coming up to the plate, looking just like the guy selling beer in the stands. That is, until he swung. Ruth was big and strong, especially compared with players of his time, and he had great bat speed. And the Yankees built a ballpark tailored to him.

David Ortiz is big and strong and has learned to fill the few holes in his left-handed swing. Manny Ramírez, when he is fully in gear, has strength and the ability to stay back behind the ball, which allows him to use nearly the entire field.

Over the course of my ten seasons in the major leagues, across more than 4,800 appearances at the plate, I was hit by a pitch only four times. Just for comparison’s sake, in the first fifteen seasons played by slugger Manny Ramírez (through 2007), he came to the plate about 8,200 times and was hit eighty-five times.

The reason why my number is so low is this: Why would they want to hit me? I was not likely to hit a long ball. And when I was hitting in front of guys like Freddie Lynn, Jim Rice, Carlton Fisk, or Carl Yastrzemski, they didn’t want me on base because those other guys could hurt them with a two-run home run.

The other reason I was rarely hit was that I was mostly pitched away, being an opposite-field hitter. I wasn’t a patient hitter, and if the count got to 3–1, pitchers were not going to try to trick me. They’d come with a fastball, and I would swing to try to get on base.

I wasn’t an ideal leadoff hitter because I didn’t walk to get on base a lot. (I averaged 1 walk for each 13.5 plate appearances. Leaving aside David Ortiz and Manny Ramírez, who get intentionally walked or are pitched around, consider the cautious and successful approach of Kevin Youkilis who averages 1 walk for each 7.4 times at the plate.)

Me, I was up there hacking.

When a pitcher throws too far inside or throws right at a batter, the natural inclination is to get out of the way. Some players, though, are willing to get hit to get on base. Done right, they can have an inside pitch just graze the shoulder or the forearm, and the worst they are going to take is one on the backside, where there’s plenty of meat. It is kind of an art; guys practice this.

Ron Hunt, then with Montreal, holds the one-season National League record for being hit by a pitch, with fifty in the 1971 season. Don Baylor of Boston got nicked thirty-five times in 1986 for the American League record; a big, strong guy, he would be right on top of the plate and just turn into an inside pitch.

Derek Jeter of the Yankees has been plunked 129 times in thirteen seasons through the end of 2007. Alex Rodriguez is close behind with 127 hit-by-pitch markers across fourteen seasons. The reason is pretty apparent when you look at their batting stance; they both stand close to the plate and in Jeter’s case he holds his hands out in the zone.

The most dangerous pitch is one that’s coming at the batter’s head. But that’s also the easiest pitch to get out of the way of, as long as the batter sees it, because all he needs to do is duck.

The pitch that’s almost impossible to get away from is one that is right at the batter’s side because it is not always clear which way to jump.

Many players today are using bats with big barrels and skinny little handles. The thinking is that the bigger barrel gives more area to make contact, while the thin handle gives a better whip. Of course, this sort of bat is more likely to snap.

And many players have switched to lighter bats, again to increase the bat speed. You might see a 34-inch bat, but it might only be thirty-one ounces in weight.

The choice of a bat is another matter of individual preference. I have seen home-run hitters who have used 34-inch, thirty-four-ounce bats, and some who swing 35-inch, thirty-two-ounce bats. Some players will go to a lighter bat as they go through the course of a season to give them better bat speed as they tire. And a player might change to a lighter bat against a hard thrower.

Here are a few choice cuts: Ken Griffey Jr. and Derek Jeter generally use a 34-inch thirty-ounce ash bat. Alex Rodriguez uses a similar bat, but an ounce heavier. Manny Ramírez also waves a 34-inch bat, but his weapon is made of maple and weighs thirty-two ounces. Prince Fielder, a rising star for the Milwaukee Brewers and a large man at 6’ and 260 pounds, uses a 33.5-inch-long ash bat that weighs thirty-four ounces. And Babe Ruth used bats like this: 35 to 36 inches long, and forty-two to forty-six ounces in weight.

Players get their order of a dozen bats and they work on them, dress them up, and put them in the batting rack, and most expect nobody else to touch them.

When I say “dress them up,” I mean that some—not all—players can be a bit obsessive about their bats. They’ll reject some bats if they don’t like the width of the grain, and they will shave the handles if the bat doesn’t quite feel right. Some will put tape on the handle for a better grip. Players will also “bone” their bat, rubbing the barrel with a bone to make it harder.

Some players are a lot more picky than others; they might get a dozen bats and only three of them will feel good enough to use in a game. They will pick out the best ones, and those will be their game bats. The rest will become batting practice bats. And there are some players who get an order of bats and just use them as they are.

Many players use pine tar on the handle to get a better grip, although most players these days use batting gloves. There are guys who put gobs of tar on the handle, and others who will just dab a little. It’s not supposed to go more than 18 inches from the handle of the bat, which was the cause of the famous “Pine Tar Incident” in 1983, when George Brett of Kansas City lost a game-winning home run against the Yankees because he apparently violated the rule; the home run was later allowed.

And then there are cheaters who might “cork” a bat. I don’t think it is widespread, but it has always been in the game and probably always will be. Players are forever trying to get some kind of an edge, and inserting some cork may make the ball jump off the bat a bit more.

There are many ways to doctor a bat, besides putting cork into the barrel. I’m told there were players who have had golf balls and other things in their bats. When I was playing, I remember hearing some batters make contact, and it sounded like a thud instead of a crack. We had a pretty good idea that something was unusual about their bats.

It is awfully embarrassing when a guy gets caught—unless you’re Albert Belle, who got caught and suspended by the league but still denied it. Or Sammy Sosa, who got caught and accepted responsibility, sort of.