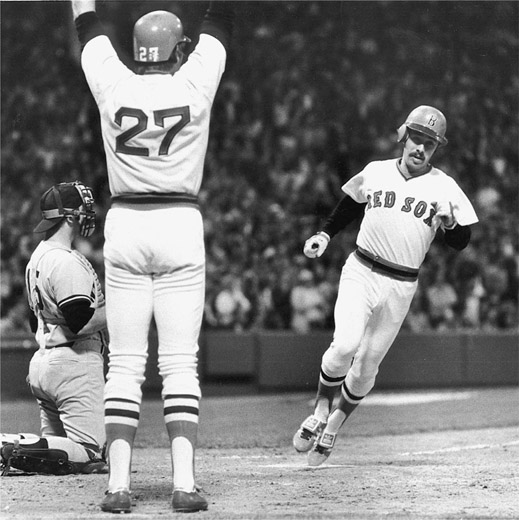

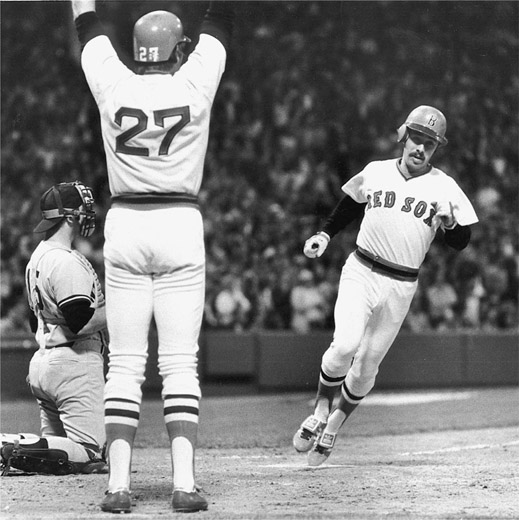

Carlton Fisk gives me the stand-up signal as I cross the plate at Fenway.

Photo courtesy Boston Red Sox

C H A P T E R E I G H T

Big guys who have power can bite with one swing of the bat. Little guys who are able to bunt can sting like a bee.

I couldn’t hurt pitchers with home runs. The only way I could aggravate them was by doing anything—including bunting—to get on base. I had more than twenty bunt hits per season a few times, and every one of them counted just as much as a line drive in my batting average. Today, though, there are not many great bunters. The game has become such a power game that even guys who have the ability to bunt don’t do it much.

One of the advantages of being known as a bunter is that the other side expects an attempt on almost every at bat. They bring the third baseman and the first baseman in close, and they may move the shortstop and second baseman to double-play positions. So before he even steps into the batter’s box, the hitter has cut down the range of the infielders. If he ends up swinging away, the ground ball that infielders might have caught if they were playing their normal positions may go through.

A bunt is a disruptive thing. It takes the pitcher out of his normal sequence, and it creates havoc in the infield. For example, if I was drag bunting as a left-handed hitter, I’d want to get three guys moving: the first baseman, the pitcher, and the second baseman. If I made a good bunt, first base would be wide open. Most batters would expect a fastball on a 2–0 or a 3–1 count, and that would be their pitch to wiggle on and hit one out of the ballpark. For me those were great counts to bunt, because I used to time everything off fastballs.

To bunt a ball, a hitter starts with the same stance he would have if he were swinging, because he doesn’t want to give anything away. He times his steps for a fastball; anything off-speed generally throws off the timing of his footwork.

As a left-handed batter, if I planned to drag the ball down the first-base line, my lead foot would angle toward the pitcher instead of down the line. Then I would swing my back leg around in a crossover step. In order for me to cover the plate, my first step would have to be toward the pitcher or toward the plate. And I would try to take the ball with me and make those three infielders move.

For a drag bunt I used to have a tight bottom hand and a loose top hand. And then I’d like a high fastball that I could push. On a drag bunt I didn’t want to deaden the ball. I wanted to hit it hard enough to get by the pitcher but soft enough that the second baseman or first baseman had to charge it.

Bunting to third base is a different story. The hitter has to wait a little longer to go into his bunting stance because he is trying to fool the third baseman and hold him back at his position. The third baseman watches the head of the bat. Once he sees the bat move into a bunt position, he is going to charge hard at the plate.

Actually, there’s a bit more finesse involved in deadening a ball down the third-base line than there is with dragging a ball to the first-base side. The batter bunts off his lead foot instead of the crossover.

For a right-handed hitter, the ideal ball to bunt down the third-base line would probably be an off-speed pitch. Once he gets his pitch, the hitter tries to deaden the ball; think of it as almost catching the baseball with the bat—as if there were a glove at the top of the bat.

A push bunt from a right-handed hitter toward second base would be the equivalent of a left-hander’s drag bunt. Again, the idea is to try to get the pitcher, first baseman, and second baseman all moving.

The key to laying down a good bunt is technique. I used to work on my bunting as much as I worked on my hitting. It was one of the things I did best, but it is the hardest for me to explain.

I would always try to drag bunt. My goal was to send the ball toward second base and have the pitcher, the second baseman, and the first baseman all moving. And eight out of ten times, with a good bunt, I could beat the pitcher to the bag. It was very rewarding to see three guys falling all over themselves trying to make a play, and it aggravated the pitcher, as a bonus.

As I’ve pointed out, with a drag bunt the batter takes a crossover step toward the pitcher and is on the move; he’s really got to get the momentum going toward first base. It’s not really like taking a swing.

I was terrible at bunting to third base. I never had the patience to stay back and deaden the ball. I always wanted to be on the move with a good jump toward first.

But I did learn to compensate later on in my career. For some reason other teams always played me in shallow at third base, even though I never bunted in that direction. So I used to try to slap the ball by the third baseman; it would go all the way to the shortstop, who was playing deep.

One reason bunting is a lot less common today is the introduction of many new, smaller ballparks. They’re home-run friendly and have accelerated the emphasis on power hitters. Another is that nobody gets a raise in his contract for being a good bunter. And many of today’s managers don’t like to give up outs with a bunt, especially early in the game.

Another of my theories involves the use of aluminum bats: Guys coming up through college and high school have played mostly with aluminum bats, and those bats are much harder to bunt with than wooden ones.

Players don’t devote much time to working on bunts during spring training and in pregame batting practice. If you watch batting practice, a player might see twelve pitches, putting down two bunts and taking ten swings. Most players treat bunts as a joke; it’s just not a part of their game.

It’s a real loss to the game, especially when a player comes up in the eighth inning in a situation where a sacrifice bunt would be appropriate, but the manager doesn’t put on the play because he knows the player can’t execute a bunt. To me that’s inexcusable. It’s a failure on the part of managers and coaches to stress that bunting is important and have the players practice it.

In today’s game there aren’t many good bunters. Ichiro Suzuki is very good, and at his peak, so was Kenny Lofton. The best I ever saw was Rod Carew. The rules say if a batter bunts foul with two strikes, he’s out, and for that reason the infield usually drops back to normal position. Carew had the ability to drop a ball down the third-base line on two strikes. He could put underspin on the ball like he was playing pool. He’d get just enough under the ball but not enough to pop it up.

Carlton Fisk would get something like ten bunt hits a year because they played him deep at third base. He dropped balls down the third-base line and totally surprised everybody. That’s ten extra hits.

If a batter is bunting for a hit, he tries to hide his intentions by waiting as long as he can before moving into a bunting stance. If he gives away the bunt too soon, infielders can react quicker. I used to try to wait until I saw the ball leave the pitcher’s hand before I started to make my move.

But a sacrifice to move a runner along is a whole different animal. Everybody in the park knows the batter is trying to lay down a bunt. With a man on first base, the hitter tries to bunt down the first-base line; the first baseman can’t react as quickly or charge hard after the bunt because he has to hold the runner on. If there is a man on second base, most of the time the bunt goes to third base to pull the third baseman off the bag to field the bunt, leaving an open base for the runner.

A squeeze play—a sacrifice bunt by the batter with a runner on third base—is one of the most exciting offensive plays in baseball and a lot of fun if you can execute it. A squeeze play’s supposed to be a surprise, or else it’s less likely to work.

As an analyst I especially enjoy calling squeeze plays. I look at how many outs there are, the score of the game, who is hitting, and who is on base. And when it feels right, I take a shot at predicting it: “There’s a good chance you may see a squeeze here.” When I get it right, I love it, because it is a play you don’t see but four or five times a season.

“Watching a situation in the game, Remy thinks of four or five different things that would never even occur to me. He’s right 95 percent of the time. The 5 percent wrong is when the manager is not aggressive enough. Jerry would be an outstanding manager.”

NESN PLAY-BY-PLAY ANNOUNCER DON ORSILLO

You will almost never see a squeeze play when there is nobody out in the inning, because there’s still a chance to have a big inning, and in any case all that is needed is a deep fly ball to bring the runner home. You’re most likely to see a squeeze with one out, because the chances of having the big inning are diminished by having an out.

There’s an important difference between a safety squeeze and a suicide squeeze. With a suicide squeeze the man on third takes off for home as soon as the pitcher’s front foot hits the ground. With a safety squeeze the batter makes the bunt and then the runner on third determines whether the bunt is good enough to get him home; if not, he stays on the base.

A good time to call a squeeze play is after a lot of action on the field in the previous at bat—when the other team may be distracted. A lot of bad stuff has happened to them, and the other side has been running and balls have been thrown all over the place. For example, after a throw comes in from the outfield and gets by the catcher, the next at bat is a perfect time to surprise the other side; nobody is thinking about a squeeze. Bing, another run.

And it makes more sense to call a squeeze not so much to tie the game but to take a one-run lead or to add another run.

Despite what I just said about not often seeing a squeeze play with no outs, in the 2007 season we saw a well-executed surprise bunt by Alex Cora in a Fourth of July game against Tampa Bay. Coco Crisp had just startled the Devil Rays with a triple to lead off the game, and Cora took advantage by laying down a safety squeeze on the first pitch he saw. Bing, bang, a run on the board and the start of a winning game.

Red Sox manager Terry Francona’s take on the Crisp-Cora one-two punch: “If it gets by the pitcher we have a rally, and [if] it doesn’t, we get a run.”

There are few scenes more sickening than seeing the batter miss the pitch on a suicide squeeze. It is deflating because it results in an easy out, removing a runner from scoring position at third base.

Managers generally use the play with a player who knows how to bunt and in a count where the batter is pretty sure he is going to get a strike. You don’t ask a guy who can’t bunt to squeeze; coaches have to have confidence that the batter can make contact, even on a bad pitch. He has to get the ball on the ground or he has got to foul it off.

In a suicide squeeze, the hitter’s intention is to just get the ball on the ground. It doesn’t have to go to third or first. There’s nothing wrong with trying to bunt it right back at the pitcher; the most important thing is to make contact.

One of the common mistakes fans make involves a situation with a man on second base. If there is nobody out and the batter hits a fly ball to right field to advance him to third, the batter is giving himself up with a productive out.

If he does the same thing with one out, it’s not much of a good thing; in that situation he is trying to get a hit to drive the runner in. But you still hear the fans give him an ovation for moving the runner along.

The difference between a straight-out steal and a hit-and-run play is this: On a steal, the hitter is not swinging.

The manager would like whoever is hitting behind a base stealer to be someone not afraid to go to two strikes. If I was up to bat and there was a speedster in front of me on first base and I saw him get the steal sign, I was not going to swing unless the count went to two strikes. Until then I would give him the chance to steal.

After the batter gets to two strikes, the batter has to be ready to swing. It drives me nuts when I hear announcers or fans say that there was a hitand-run on a 3–2 count.

Watch the counts: 1–0, 1–1, and 2–1 are hit-and-run counts. If the count goes to 2–0, the manager is probably not going to call for a hit-andrun because that’s where he wants the batter to try to hit one out of the ballpark.

Another way to spot the difference between a hit-and-run and a straight steal is to watch the runner carefully. When a player takes off on a hit-and-run he usually will take a peek back toward home plate while he runs to see if contact was made and where the ball was hit. If you watch base runners on a straight steal, you’ll see most won’t even look at home plate. Or at least they shouldn’t.

You also need to pay attention to the situation in the game. If a team is down by three or four runs, they’re not likely to put on a hit-and-run. It’s a bad idea because the manager might be forcing that hitter to swing at a bad pitch and make an out. A manager generally calls the play when his side is ahead or down by one or two runs. But some managers will put on a hit-and-run just for the hell of it because their team has really been struggling and they’re trying to open up a hole and get something going.