C H A P T E R T E N

When we talk about a good infielder, we might say he has “good hands.” There are some fielders who jab at balls and others who look so smooth. There are some who attack balls and those who let the ball come to them.

Watch players take ground balls during infield workouts; what you see in practice is probably what you’ll see in the game.

Good infielders always seem to play the right hop. They don’t get fooled by bad hops. They get themselves in good position to make that smooth play. You can clearly see how some players funnel the ball from the ground up to their body, and it’s so smooth: good hands. Other guys seem to be fighting it all the time. In Boston I played for a couple of years with Rick Burleson, who was not the classic smooth shortstop. He jabbed at balls, but he got the job done.

The feet are the base for everything in baseball; if a fielder doesn’t get his feet in the proper position, his hands are going to be all over the place. A guy like Derek Jeter is smooth; he always seems to have his feet in the right spot. The same thing goes for Alex Rodriguez.

A lot of an infielder’s work, especially at second base and shortstop, is anticipating where the ball is going to be hit. He’s got to know the difference between a sinker-ball pitcher and a power pitcher. He’s got to know who is at the plate and how the batter deals with different types of pitches. And he needs to pay attention to the count. There are certain hitters who are probably going to pull the ball in a hitter’s count.

Then there’s the choice of pitch. Many right-handed hitters tend to pull a curveball; an alert fielder knows that and takes a few steps to his right. Similarly a left-handed hitter will often try to pull a sinker ball, so that should take an infielder a couple of steps to his left.

In general, when there is a right-hander at the plate, infielders might shade toward first—not a huge adjustment, maybe a step. But it all depends on that hitter: Does he change his swing with two strikes? Does he cut down on his swing to try to make contact?

You can usually spot the difference between a seasoned veteran and a rookie, even a very talented one. In a word, this is a matter of experience. A kid may come up to the major leagues as an outstanding fielder, looking beautiful taking ground balls and showing a great throwing arm. But he doesn’t know the hitters and he doesn’t really know his own pitching staff. And he’s got to learn it on the job.

When I look at an inexperienced infielder, I usually find a guy who seems to be just missing ground balls by inches. It may just be a matter of not being in the proper position.

If you’re watching the replay of an error on the stadium screen or at home, see if the fielder jabbed at the ball or played it smoothly. You can’t be a good infielder if your glove is hanging around your stomach and you are reaching for balls. If that’s the way you play, you become a jabber.

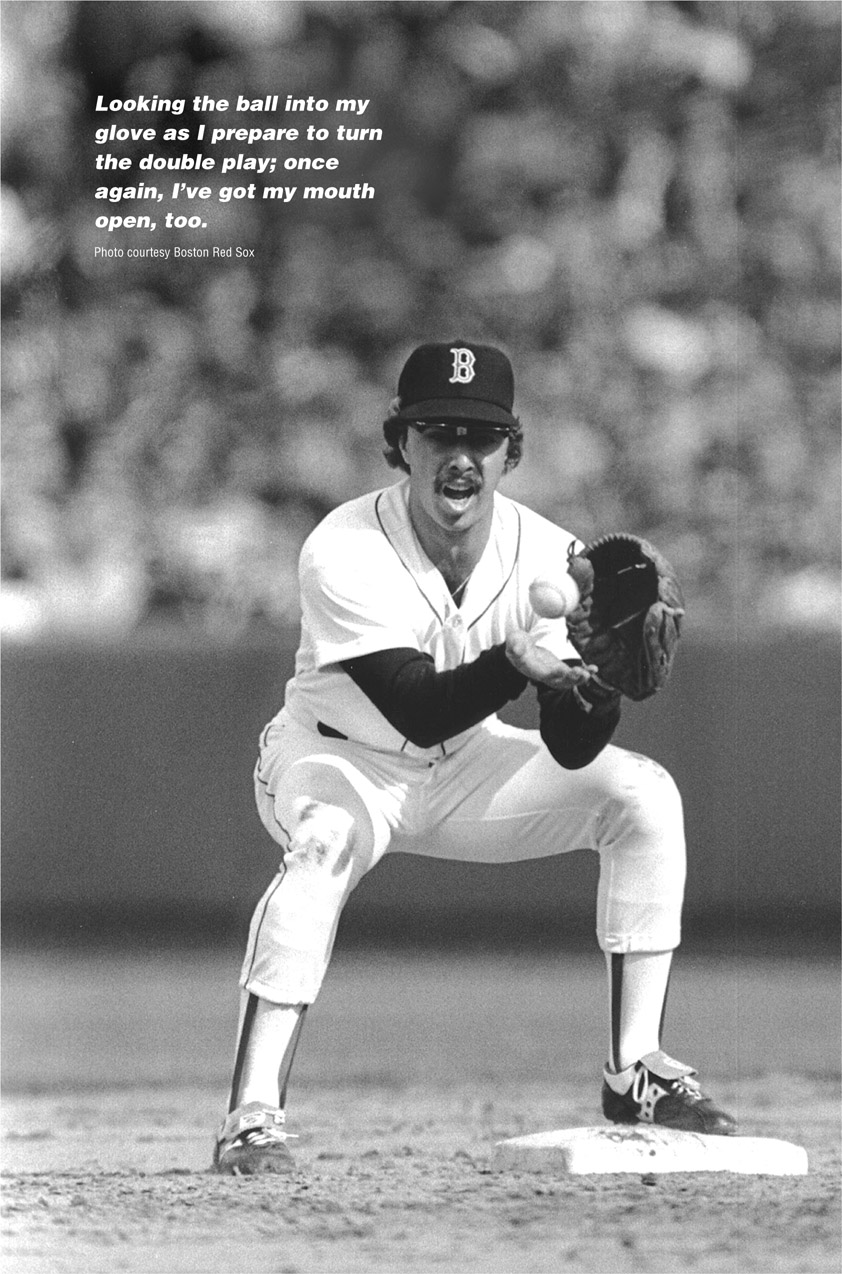

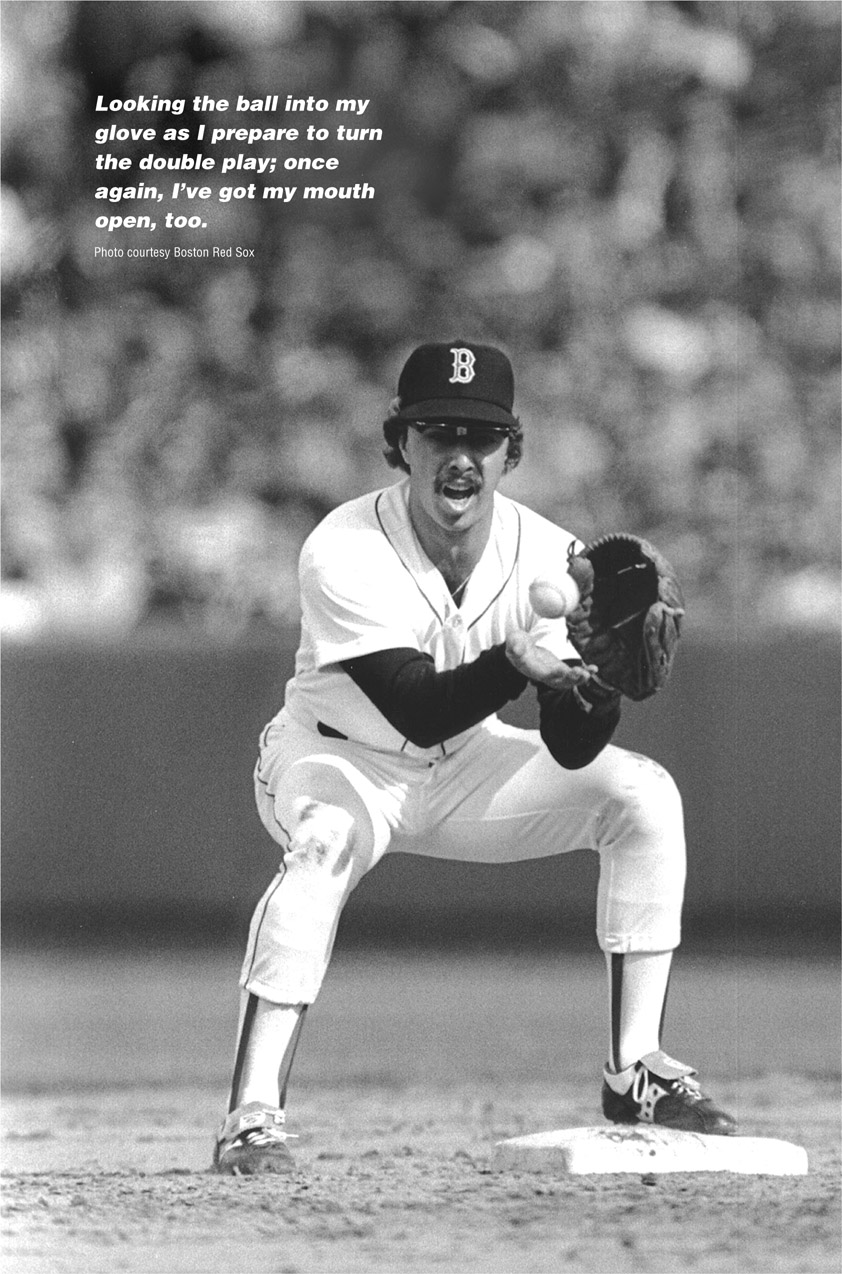

A good infielder tries to work from the ground up. He holds his glove low, with knees bent and butt down toward the ground. He squares up to the ball, keeps his eyes on the ball, and tries to follow it right into his glove.

At shortstop and second base, fielders try to get in a rhythm, so that when the ball is delivered to home plate, they’ve got a little momentum going either toward first base or back and forth between their normal position and one of those bases. It helps them get a good jump on the ball.

First basemen also try to be on the move, unless they are holding a runner on.

Third base is a reaction position. A lot of third basemen do not make any side-to-side movements or take a step in. Balls are usually hit so hard to third, and they are so close to the hitter, that their most important step is the first step, a reaction step.

I’ve always thought that the idea of a “marriage” between the second baseman and the shortstop is a bit overrated. People like to say, “There’s such a comfort level there because they’ve worked together for such a long time.”

The two fielders have to know each other’s abilities and habits. Where is this guy going to give me the ball as I am trying to turn a double play? And at what velocity is it coming? That’s all either really needs to know to make the “marriage” work.

Obviously, it is much easier to be out there with someone you play with every day because you know where the throw is going to be. On the other hand, I don’t think it takes all that long to get to know somebody, at least when it comes to baseball. I could go out with anyone and take ground balls for five minutes, and I would have a pretty good idea where I’m going to get the ball. For example, if a shortstop is going toward the bag, as a second baseman I would expect him to give me an underhand flip. In that case I know that I can come across the bag.

If the ball is going to be right at him, does he go with the underhand flip or does he like to make the throw sidearm? If he throws sidearm, as the second baseman I’ll have to be a little bit more defensive around the bag because I don’t know where the ball is going to go.

The plays that are tough are the ones where the shortstop has to go to his right toward third base, backhand the ball, and throw off-balance. He is going to try to give it to the second baseman in front of the bag, but if he is off-balance, the throw could be behind the bag.

As a second baseman, I always found it more difficult reading my third baseman than reading my shortstop. The third baseman has a longer throw, so there is more chance for an error or a bad throw.

With a throw from third, you’ve really got to be patient. You’ve almost got to straddle the bag, and always anticipate a bad throw.

There are three basic positions for infielders: infield back (near the outfield grass), double-play depth, and infield in (on the infield grass).

In the best of all possible worlds, an infielder likes to play as far back from the plate as he can get away with; this gives him extra time to play a ground ball or grab a line drive. Of course, he can’t play too far back or he won’t be able to throw the runner out at first base. And if he plays too far back against a good bunter, the batter can make him look foolish by dropping a dribbler in the infield.

To turn most double plays in the infield, a fielder has to get to the ball as quickly as possible and get it to the other middle infielder in enough time to allow him to throw on to first base to get the batter. If they play back, they often can’t do that; it would just take too long.

Double-play depth moves the infielders somewhere between the infield-back and infield-in positions, a little bit deeper than halfway between the edge of the infield and the outfield. The second baseman and shortstop also move a step or two closer to second base than usual. This repositioning comes with a risk: A fielder will not get to a ball he could have reached if he was in the normal infield position.

As always, it’s important to know the opposing players. If the runner on first can motor, you might see the fielders place themselves directly in the middle of the infield, so the shortstop or second baseman doesn’t get killed on a relay. If there’s a guy at bat who can really run, like Ichiro Suzuki, a team might not go to double-play depth at all, because they figure they’re probably not going to double him up.

With a runner on third and fewer than two outs in a close game, most teams will bring the infield in to increase the chances of making a play at the plate. As with double-play depth, a drawn-in infield limits the range of the infielders. A ground ball two steps to the right or left is probably going to get through.

The decision to gamble on playing the infield in should depend on who is hitting, who is pitching, and who is running at third base. If there is a slow runner, infielders don’t have to play all the way in and instead can play back four or five steps. Even if the infielders take just a step or so in toward the plate, the third-base coach will probably tell a slow runner not to go home unless the ball gets through to the outfield.

“Jerry Remy was a scrappy little ballplayer who didn’t think he had played the game unless he got his uniform dirty. He was not the best second baseman who ever played, but he tried to be.”

DAVE NIEHAUS, VOICE OF THE CALIFORNIA ANGELS FROM 1969 TO 1976 AND THE SEATTLE MARINERS FROM 1977 TO THE PRESENT DAY

The manager will also look at where the other team is in its lineup. If it is toward the bottom of the lineup—presumably with weaker hitters—you’re liable to see the infield in. If the power hitters in the middle of the lineup are up, the infielders may stay back.

Sometimes a manager will draw in the infield early in the game, even in the first inning. He might do this when there is a great pitching matchup, for example. The manager may figure in that game there are not going to be a lot of runs scored, so he would try to cut down runs as early as possible. One run may be the difference in the game.

I remember as a player going up against teams managed by Gene Mauch; he always brought the infield in early in the game, no matter who was pitching. Mauch always wanted to be ahead in the game.

Let me take you back to the seventh game of the 2001 World Series, not just because the Yankees lost but because it was a perfect example of the difficult situation faced by managers when the winning run is in scoring position.

Luis González of the Arizona Diamondbacks came up to the plate with bases loaded and one out in the bottom of the ninth inning against the New York Yankees. He was facing Mariano Rivera and his almost-unhittable cut fastball.

Remy Says: Watch This

The Making of an All-Star Shortstop

What separates an All-Star from an average player? Arm strength, the ability to make backhanded plays, range going to his left and his right, and positioning.

A shortstop doesn’t need to have great speed, but he does need quickness, which creates some range. He needs a strong throwing arm, or a very quick release, and good hands. There are a lot of infielders who have some of those weapons, but there are very few who have all of them.

You would certainly include Cal Ripken among great shortstops, but he did not have all the tools that Alex Rodriguez had when he played short, or that Derek Jeter or Orlando Cabrera have. But Ripken made it look easy because he always seemed to be in the right position.

With a sinker-ball pitcher in the game, a manager could reasonably expect the hitter to hit a ground ball, and so it’s an easy decision to bring the infield in. However, Rivera doesn’t get a lot of ground balls; he is a strike-out/fly ball pitcher. With that kind of pitcher, the manager might not ordinarily draw in the infield. But in a World Series, if there was ever a ground ball hit by accident and the manager had the infield back, he wouldn’t be able to live with himself. He’s just got to try to cut down that run.

Former Yankee manager Joe Torre pulled the infield in, drawing shortstop Derek Jeter out of position. González choked up on the bat—something he hadn’t done all season—and flared a single right over Jeter’s head. If Jeter had been in his normal position, he probably would have caught the ball for the second out, and the Yankees would have had a good chance of surviving the inning and taking the Series into extra innings.

It always looks bad when the infield is pulled in and a guy drops a hit a few feet behind the infield, which is exactly what happened.

Managers are second-guessed all the time. He makes his decision. If it works, great; if it doesn’t, he’s still got to do the same thing next time. Joe Torre never backed down from his decision, and I agree with him.

Late in the game when their team has the lead—usually from the seventh inning on—managers will often have the first baseman and third baseman guard the baselines. They move closer to the lines to try to prevent an extra base hit that goes down the line and into a corner of the outfield. This is a manager’s call, a flip of the coin. Certain managers will even do it with two outs right from the start of the game to try to keep a man out of scoring position at second base.

It’s always been a weird concept to me because you are penalizing yourself for being ahead in the game. You are moving one or two players out of position because you have a one-run lead.

Some managers feel the same way I do. They’d rather take away the base hit, because the double is harder to get than the single. And you’ll see this situation come up when there is a great base stealer up to bat. Why play the line? If he gets on first, he’s going to steal second anyway.

Now there is another situation when a team might want to play the lines: if there is a man on first who represents the tying or winning run. In that situation you may see infielders playing the lines and outfielders playing the gaps and standing deeper. They’re trying to prevent the extra base hit that might score the man on first.

Once again, though, it depends on the hitters. If there’s an opposite-field hitter at the plate, like I was or like Wade Boggs was, why play the first baseman on the line? An opposite-field hitter would never pull the ball down there. But a team might take the third baseman and put him on the line to try to prevent a double.

Positioning also depends on the ballpark. At Fenway Park, for example, a ball down the third-base line is not guaranteed to be a double because of the way the wall comes out. Many times you’ll see a ball hit off that wall and come back out onto the field, and the fielders can hold the batter to a single. Some managers won’t play the third-base line at Fenway.

The toughest guys to defend against are hitters who use the whole ballpark. When you see one of the better batters come to the plate, you’ll probably see the infield and the outfield straight up, not shading one way or the other.

If one of the best batters is down in the count, he’ll move the ball to the opposite field. If he gets a certain pitch, he’ll pull it. If he’s thrown a high fastball, he’ll go the other way or up the middle.

I think of a guy like Rod Carew, who was impossible to defend against. We used to go over him in pregame meetings and ask, “How are we going to pitch this guy?” Nobody had an answer. So the pitcher would throw Carew breaking balls and hope that he got himself out.

There was no way to set up a defense against Carew because he would go line to line. He’d hit a ball down the leftfield line on the chalk and the next time he hit down the rightfield line on the chalk. Then he’d bunt with two strikes.

Some batters are so predominately pull hitters or opposite-field hitters that it makes sense to put on a defensive shift in the infield. For example, against a right-handed opposite-field hitter or a left-handed pull hitter, a team might move the shortstop behind second base or even put both the shortstop and the second baseman on the right side of the infield.

The manager is hoping either that the shift will improve the chances of making a play, or that it will convince the batter to go against his natural style and give up some power or ability to hit the ball.

The most famous such alignment was the “Williams Shift,” first employed by the Cleveland Indians against Boston’s Ted Williams. The defensive alignment was designed by Cleveland’s Hall of Fame player-manager Lou Boudreau; interestingly Boudreau ended up his career playing for Boston in 1951, and then managing Williams and the Red Sox from 1952 to 1954.

On the Red Sox the guy who most often is greeted with an extreme shift is David Ortiz, a left-handed hitter who tends to pull the ball to the right side of the infield when he hits it on the ground or on a line; when he puts it up in the air he can tattoo the Green Monster in left field or put it out of the park almost anywhere else, but there’s no defending against that.

Some opposing managers bring the shortstop to the right of second base and the second baseman into a midway location at the lip of the outfield grass. Ortiz hasn’t made much of an adjustment and that’s probably good because it has not screwed up his swing. He still gets his share of hard-hit balls that get past infielders wherever they are.

I remember one series the Red Sox played against Seattle when Ken Griffey Jr. was with them, and he was hitting a lot of home runs. Red Sox manager Jimy Williams put the shift on him. It got to Griffey and took him out of his game. He was thinking, “I’m going to bunt to third because I’ve got nobody over there. I’m going to get a base hit.” The Red Sox were perfectly happy; they’d rather have Griffey get a base hit than a home run.

Most players say “to heck with the shift, I’m just going to take my at bat. I’m going to have the same swing.” And that is what you should do.

At the start of a new series, most teams have a meeting to discuss their new opponent. Some managers are very focused on detail, using charts. Others rely strictly on an advanced scouting report or what they saw the last time they played against the team.

Dick Williams, my first manager at the major league level, was very much into the details. He had everything charted: every single pitch against every hitter. In those days that was unusual.

When I came to Boston a few years later, Ralph Houk basically planned his game based on what the other team had done against us before and what the advance scout might have seen in the last three games they played.

Today it is very different. Every team has an electronic library and hitters can study every at bat against a particular pitcher over the last five years if that’s what they want to do. They can do it before the first pitch, or even duck into the clubhouse during the game.

And the same goes on defense. There will be a coach who handles the infield and a guy who is in charge of the outfielders. They’ll have a plan prior to a series, and they will make adjustments as they go along. Watch the dugout and you’ll often see a coach on the top step moving an outfielder or signaling to the infield.

As with most everything else in baseball, there is no one-size-fits-all rule for how to set up the infield when a right-handed pitcher is throwing to a left-handed batter, or any other pitcher-batter combination. It depends whether this left-handed batter is a pull hitter, an opposite-field hitter, or a straightaway hitter. And it is also affected by the game situation.

Let’s say there is nobody on base and there’s a left-handed pull hitter facing a pitcher who is not overpowering. In that instance you can expect the batter to pull. So obviously the whole infield can shift around toward first base—a step or so left. Or let’s say a batter has faced Josh Beckett twenty times in his career. The Red Sox would have a pretty good chart that the coaches can consult to see where he has hit the ball, and the team can set up a defense based on his history.

And things may be quite different with the same batter against a different pitcher. When knuckleballer Tim Wakefield is throwing, for example, the Red Sox play everyone to pull because the pitch is coming in at about 60 miles per hour and most guys are going to swing early and pull the ball.

Pay attention, too, to the outfield. You’ll see quite a few situations when the infield might be shading a batter to pull, while the outfield will be shading him to the opposite field. That’s because the charts say that when he hits the ball in the air, he usually hits the other way, but when he hits it on the ground, he pulls it.

Left-handers tend to have more movement on their pitches than right-handers. And right-handed hitters, going back to when they were kids, mostly saw right-handed pitchers. Even going through pro ball, they don’t see that many left-handers. So let’s start with the fact that many right-handers hit right-handers better or are least more comfortable against right-handed pitching than they are against lefties.

Obviously there are different styles. Take a guy like Randy Johnson; when he was at his peak, he was a power left-hander: A smart hitter’s approach to him will be different than when he is facing another successful veteran like Jamie Moyer, who relies not on power but instead on control. When right-handers try to pull Moyer, that’s exactly what he wants them to do.

Tom Glavine is another example of a control pitcher, a likely Hall of Famer who played for Atlanta for sixteen seasons and was still winning for the New York Mets at age forty-one in 2007 and probably has a few more seasons in his arm. He stays away from right-handers and changes speeds from fastball to changeup. His goal is to keep the batter off balance and make him try to pull the ball. If the pitch is down and away and a right-hander tries to pull it, most of the time anything he hits is going to be on the ground and to the shortstop. If you see a lot of ground balls to shortstop and third base when Glavine is pitching to a right-hander, he is doing his job and the hitter is not. The hitter should be thinking about going up the middle.

One of the best indicators of a good defensive team is whether fielders change their position depending on the count. If they don’t move, they’re probably not a very good defensive club. But if you look out as the count changes and see the center fielder move a couple steps to his right, the right fielder come in a couple of steps, and the third baseman come off the line, you know that the team is pretty well prepared defensively. They may not be the best defensive team, but they know what they want to do.

Moving on the count is important, because batters adjust their swing when they are behind in the count. For example, if a good hitter has two strikes against him, he’ll cut down his swing in hopes of making contact with the ball. That makes it more likely that he’ll hit the other way and the ball won’t travel as far. And so, with a good right-hander at the plate, you’ll see the right fielder move in a little bit or stand closer to the line.

If the batter is not a great hitter, a guy who strikes out a hundred times a year and is a dead-pull hitter, he’s not going to cut down on his swing with two strikes. He’s going for it, so fielders wouldn’t make that adjustment.

Some players know enough about the game and the other team to position themselves properly. You expect the veteran player to move more on counts than you would a younger player. But others let the coaches think for them. That’s why you see the coach at the top step of the dugout, getting their attention. Some teams have even placed scouts in the press box or on an upper level with a radio so they can report if a fielder is out of position.

The second baseman and the shortstop have the advantage of being able to see the signs flashed by the catcher to the pitcher, and they can adjust their position to try to anticipate the type of swing the batter will make. They can, in turn, give some kind of an indication to the first baseman and third baseman about the coming pitch.

Of course that means that the infielders have to know the sequence of signs used between catcher and pitcher, including any changes made during the game. Now here’s where the scouting report on the hitter comes into play. What has this guy done on curveballs from this pitcher before? Has he pulled them all? Will he pull this one, or will he try to take it to the opposite field? When a fielder knows what his pitcher is about to throw, he can adjust his position accordingly.

An infielder can’t make a move too soon or he’s going to give the pitch away to the hitter. A smart hitter can figure out the type of pitch if he sees the infielders shift. At times in his younger days Cal Ripken was too obvious about his positioning.

If a right-handed hitter sees the second baseman take a couple of steps to his left, he’s got a pretty good idea he’s going to see a fastball away. If the second baseman is standing where he is, it might be a fastball in, or it could be a slider or something that may fool him a little bit. If he sees the fielder take a step to his right, he can be pretty sure he’s going to see a changeup or a big curveball, depending on what the pitcher can throw.

Rem Dawg Remembers

The Splendid Splinter

You don’t see many great hitters that are strictly pull hitters. There have been some: Ted Williams, for example, and Barry Bonds.

An infielder will sometimes see a batter make an adjustment in the box. This could make him change his defensive position. For example, if he sees the batter change to an open stance instead of a straightaway stance or a closed stance, that means he’s probably trying to pull the ball. If he closes his stance up more, he’s trying to go up the middle or the other way.

On rare occasions you’ll see a guy choke up on the bat a little bit; this is less common today than it was in the past. This is another instance when fielders have to know the hitter. A good infielder (or the defensive coach in the dugout) will know that certain hitters change their swing when they’re down two strikes and try to poke the ball somewhere and beat the throw for a hit.