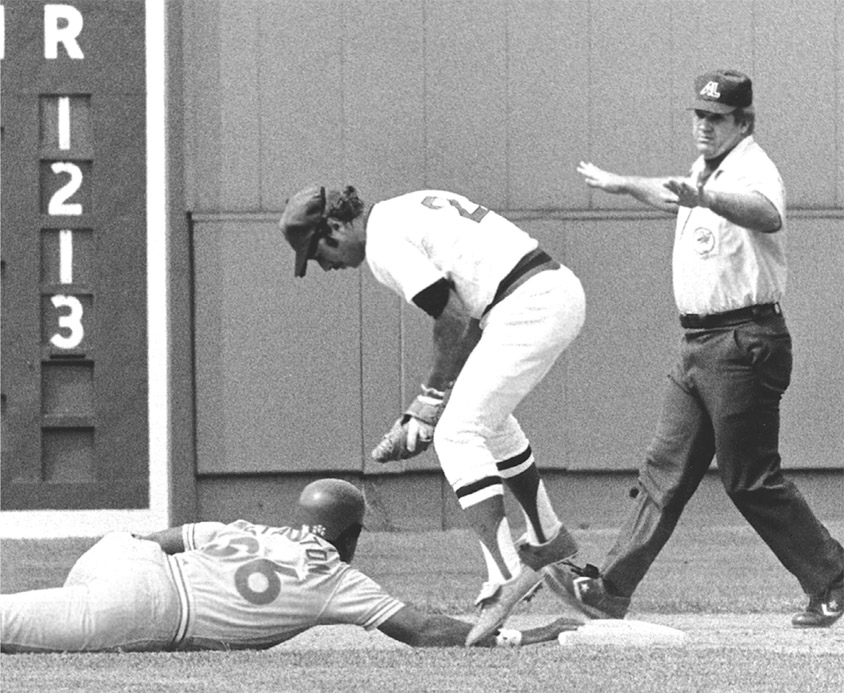

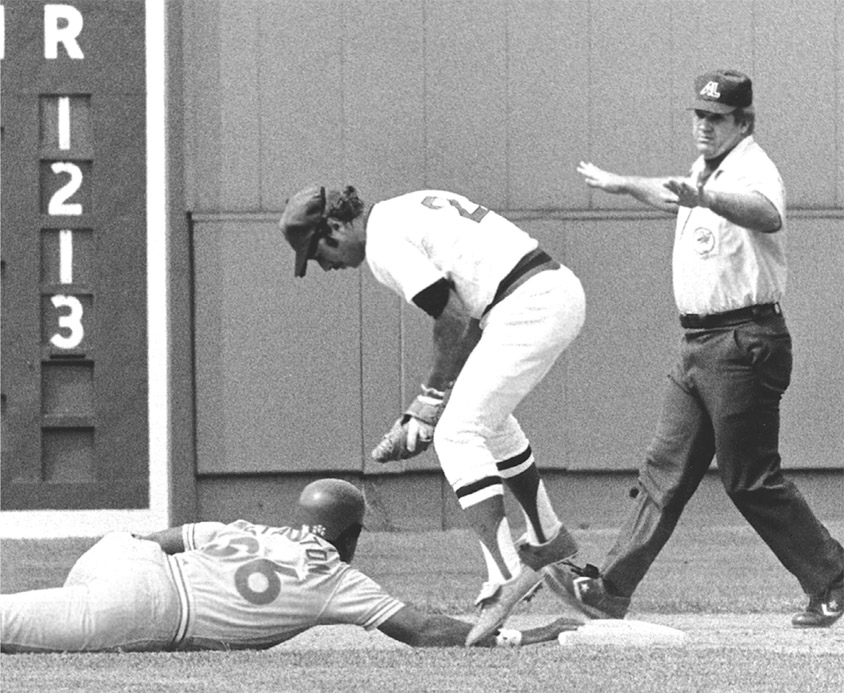

The pitter-patter of little feet on an unsuccessful pickoff attempt at second base.

Photo courtesy Boston Red Sox

C H A P T E R E L E V E N

When there is a runner on second base, the shortstop and the second baseman have to agree who is responsible for keeping him close to the bag. As a rule, if a right-handed hitter is up to bat, the second baseman has that job, and if a left-handed hitter is at the plate, the assignment goes to the shortstop.

But that assumes the batter is a pull hitter: a right-hander who is likely to hit to the left side of the field, or a left-hander likely to hit to the right. If instead a right-handed batter is an opposite-field hitter, the second baseman should move more toward first base and the shortstop should step toward second to hold the runner; they’d step the other way for a left-handed opposite-field hitter.

It doesn’t matter so much what pitch is thrown. What matters is where the batter typically hits the ball.

The second baseman has to communicate with the shortstop: You keep him close or I’ll keep him close. It’s usually done pretty openly because it’s obvious to the base runner. If the runner looks at the second baseman and sees him way over toward first base, he knows that fielder is not responsible for holding him. He knows the shortstop is right behind him.

If it’s a hit-and-run situation and the catcher has called for a curveball, the second baseman might tell the shortstop to stay at his regular position with a right-hander at the plate because the hitter may pull the ball.

Teams try to guess based on the percentages, the pitcher, and the hitter . . . and they hope they guess right.

Sometimes the best drama in a ball game is the result of an infield pop-up near the mound; it’s not supposed to be that way, but things can easily fall apart if players forget their assignments.

The basic rule is that on the left side of the infield, the shortstop has priority over the third baseman; on the right side the second baseman has priority over the first baseman. The first baseman and third baseman have priority over the catcher.

Generally the pitcher is not even in the play. That seems foolish to me; some pitchers can catch fly balls as well as any other infielder. But they are almost always called off.

On a pop-up behind first base, the second baseman usually can make the play. He is deeper than the first baseman to begin with, and he has a better angle on a pop-up and an easier chance. The same applies on the left side of the infield, where the shortstop is usually better able to make a play behind third base than the third baseman. The shortstop is coming toward the ball, while the third baseman would have to back pedal or turn around and run toward the outfield.

If the ball is popped up between home plate and one of the bases, the first baseman or third baseman has an easier play because he is coming in on the ball. It’s more difficult for the catcher because the ball is going away from him; when a catcher goes out into the infield to make a play, he usually turns his back to the infield so the ball comes to him.

When a pop-up makes it to the outfield, the center fielder has priority over the right fielder and left fielder. And any outfielder has priority over an infielder, if they can get to the ball. Again, the outfielder has an easier play because he is coming in on the ball instead of chasing it toward the fences.

We’ve looked at bunts from the point of view of the hitter; now let’s look at the defense. There are three types of bunts:

“He does everything well. He has tremendous speed, he hits to all fields, he throws well, he makes the pivot perfectly, and he’s not afraid of the pitter-patter of little feet.”

CALIFORNIA ANGELS MANAGER DICK WILLIAMS SPEAKING ABOUT JERRY REMY IN 1975

The basic sacrifice bunt is put on when there is a man on first and fewer than two outs. The strategy on defense is like this:

Remy Says: Watch This

Fair or Foul?

Among the oddities of baseball is the fact that first base (like third base) is on the fair side of the baseline, but the base path from home plate to first is in foul territory. So, when a batter makes contact and takes off toward first base, he starts out on the wrong side of the baseline. Ordinarily, this is not a problem unless there is going to be a ball thrown from the catcher or the pitcher. If the runner is in the way of the throw, the umpire is supposed to call him out.

You will very seldom see the umpire call a runner out for being on the wrong side of the baseline on a throw from any infield position other than the catcher and occasionally the pitcher. But it is almost automatic that if he gets hit in the back with the ball, he is going to be out.

On a close play at first, the runner is taught to run through the bag in a straight line; of course, if he does that, he’s going to be on the wrong side of the baseline. He’s running as hard as he can to beat the throw, and it is usually stunning if the umpire calls him out.

It is very important that an infielder doesn’t give up his position too soon on a sacrifice bunt. If he moves too soon, he’ll leave a wide-open gap in the infield. A smart hitter, a guy who can handle the bat, will just turn around and try to punch one through the hole.

There are situations when the defense against the bunt may be different. Let’s say a team has a two-run lead late in the game, and the other side has runners on first and second. Here it is likely the team at bat is going to bunt. But in this situation, the runner going to third is not as important. So you might see the shortstop go to second base and the third baseman field the ball and throw to the shortstop to get the runner out at second base, erasing the potential tying run.

If the batter attempts a squeeze play with a runner on third base, the third baseman’s basic assignment is to yell out that the runner is going. But even before that happens, if there’s a man on with some speed, the third baseman should be thinking about the possibility of a squeeze.

Before the play, the third baseman should be also paying attention to the other team’s third-base coach and the runner. He yells to the pitcher and catcher, though it’s usually too late to alert the pitcher, who can see the batter squared to bunt, anyway.

As far as the team that’s up at bat, on a squeeze play the coach gives a sign to the hitter, and the hitter usually flashes a return sign to the coach to acknowledge that he’s got it. Then there’s usually a vocal signal to the runner.

To defend against a bunt for a base hit, infielders have to know if the hitter is likely to try a drag bunt, or if he likes to bunt down to third base. The basic idea of a drag bunt is to push the ball by the pitcher and get the pitcher, the first baseman, and the second baseman all trying to make a play on that ball, leaving nobody to cover the bag.

Some teams have the first baseman stay near the base while the second baseman charges to make the play. If they get it, they get it. If not, it’s no big deal. But at least they have somebody covering the bag.

When there is nobody on base, on any play being made to first base, the second baseman’s responsibility is to go over there and at least be in the vicinity. If the ball gets by the first baseman, that gives the second baseman a chance to track it down. The second baseman determines his angle to the ball based on where the ball is being thrown from.

Anytime there is a man on base, the second baseman or the shortstop should take a couple of steps behind the pitcher when the catcher throws the ball back. It almost never happens, but there’s a chance that the ball can get away from the pitcher. You’ve got to be there to make the play.

If there is a right-handed hitter at the plate, the second baseman usually backs up the pitcher; with a left-handed hitter at bat, it is usually the shortstop who steps toward the mound.

You don’t see this as much as you used to, but you should always see the throw backed up when there is a man on third because an error could mean a run.