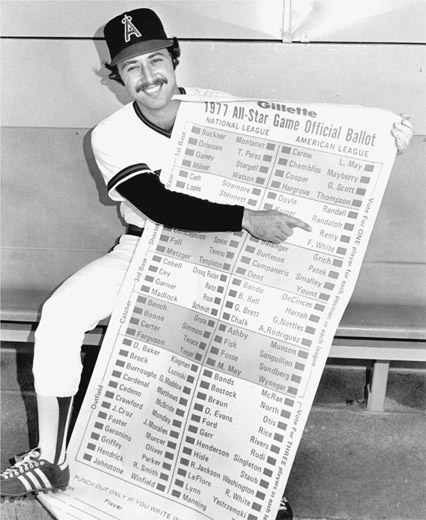

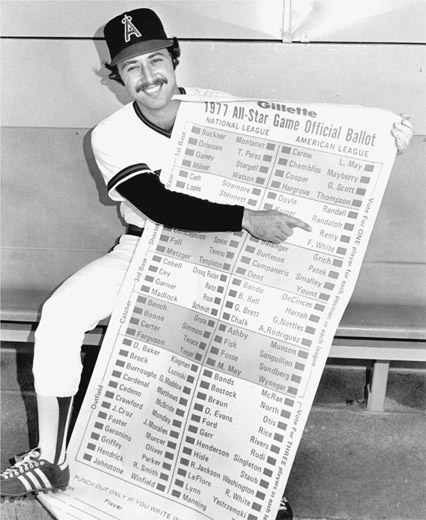

Despite my campaigning in this 1977 publicity shot for the Angels, I didn’t quite get enough votes to make the All-Star team that year. But I was chosen in 1978 in my first year with the Red Sox.

Photo courtesy Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim Baseball Club

C H A P T E R T W E L V E

The first baseman’s most important skill is the ability to make plays in the dirt. A good first baseman can save infielders many errors if he can handle bad hops and bad throws. If the infielders know they’ve got a good first baseman, they know every throw does not have to be perfect; this guy is going to bail them out. It’s almost like the confidence the pitcher has in his catcher.

A good first baseman can also dive and knock down a ball hit down the line, preventing an extra base hit: Keith Hernandez was good. George Scott was terrific.

Don Mattingly was so pretty to watch when he played first base; he had tremendous range to his left and right. He could make the 3–6–3 double play (first baseman to the shortstop covering second and then back to the first baseman) look beautiful. More recently, John Olerud and Travis Lee were among the game’s best first basemen. Olerud, who retired after the 2005 season, was great on balls in the dirt. Former Red Sox Doug Mientkiewicz, was also one of the best; in 2007 he was defensive specialists for that American League team in New York. From 2003 through 2005 the most-used Red Sox first baseman was Kevin Millar, who is right-handed, instead of David Ortiz, a lefty who was used primarily as the designated hitter. First base is sometimes difficult for really big guys like Ortiz, although he does a more-than-adequate job in the field. Ortiz can catch the ball well and can save you on high throws, but it is tough for him to get down on ground balls.

Kevin Youkilis took over at first base in 2006 and quickly showed he had exceptional talent for the position. On June 25, 2007, he played in his 120th game at first without an error, breaking the Red Sox record set in 1921 by Stuffy McInnis. On September 7, he played in his 179th consecutive errorless game, breaking Mike Hegan’s 1973 American League record.

His streak continued to the end of the season, reaching 190 games, and will resume with the start of 2008; he could break the major league record of 193 games held by Steve Garvey. (Youkilis was charged with a tough fielding error on a foul popup in the ALCS against the Cleveland Indians, but postseason errors are a separate category.)

Youkilis’s streak is even more amazing considering that he did not come up to the majors as a first baseman. He was primarily a third baseman, and had also played second base and left field. And he made his professional debut as a catcher for the Lowell Spinners. (He is unofficially the emergency third catcher for the Red Sox but has never had to put on the tools in the majors.)

First base is made for a left-hander. With the glove on the right hand, he can better cover the hole between first and second. On tag plays and pickoff attempts, he just grabs the ball and slaps it down. On bunt plays he doesn’t have to spin around to make the play, something right-handers have to do.

The only play that is especially difficult for a left-hander at first base is a backhanded play right down the line.

Nevertheless you’ll see mostly right-handers playing first; there are simply more of them. The forehand play for a lefty in the hole between first and second becomes a much more difficult backhanded play for a righty. On a throw to second base, for example a 3–6–3 double play, a right-hander has to field the ball and make a jump pivot; a left hander just makes the catch, takes a step, and throws. On bunt plays a right-hander has to spin or turn all the way around to make a play at second or third base, while the left-hander is in position as he fields it.

The one place where it is an advantage to be a right-hander is a shot down the rightfield line, because his glove is on his left hand.

On some teams first base is a place to park a so-so fielder with good power or a star who has lost range but can still hit. This may not be the most popular thing with other infielders, but it is a way to get a good bat into the lineup.

“People say I don’t have great tools. I make up for it in other ways, by putting out a little bit more. That’s my theory, to go through life hustling. In the big leagues hustle usually means being in the right place at the right time. It means backing up a base. It means backing up your teammate. It means taking that headfirst slide. It means doing everything you can do to win a baseball game.”

PETE ROSE

A team will almost always sacrifice defense for offense at first base. If there’s a big bomber over there—Jim Thome is an example, a guy who can hit 50 home runs a year and drive in 140 runs—most teams will accept some bad first-base play. (Thome was injured for most of the 2005 season, and he has played mostly as a DH for the White Sox in 2006 and 2007.)

An advantage for the first baseman is that he uses a big glove. He doesn’t have to be perfect on the fundamentals, and he doesn’t have to be the prettiest or the smoothest fielder. If the first baseman can knock the ball down, he still has a chance to get an out. The pitcher should be covering, and he can take a little underhand flip.

The first baseman also doesn’t need to make many throws. If he’s got a bad arm, he can hide it most of the time. There are some first basemen who will not make a throw on a bunt. Batters can bunt on them all day long because they’re not going to try to get the lead runner at second base. In the 2002 All-Star Game, Jason Giambi dove and tagged first base on a bunt when he had all kinds of time to throw to second base. He just didn’t want to throw there.

There are, though, a lot of things that can go wrong around first base that can cost runs. You’ve got to be smart.

For example, let’s say there is a ball hit to the infield with a runner on second base and a bad throw is made to first base. Does the fielder try to make the great play and pick the throw out of the dirt—and maybe not get it—or does he come off the bag and block the ball, giving up the out?

By blocking it, at least that run is not going to score from second base. If the first baseman tries to make a pick on a bad throw and doesn’t make it, it’s a gift run.

First base is probably the gabbiest position. There is a lot of activity there: The first baseman has the first-base coach, runners on the other team, and his very own umpire to chat with.

Many of the conversations are about the batter’s last at bat or about the pitcher or the weather. It’s usually not very significant stuff.

Most of the time when I got a hit, I was so happy to be on base I didn’t even hear what the first baseman had to say. I do, though, remember early in my career I was struggling and got to first, where Dick Allen was playing the bag; he was with Oakland at the time, at the end of his career. He said to me, “How are you doing?” I said, “Struggling.” He told me, “Kid, a slump is only as long as your last time at bat.” Words of wisdom.

Anyhow, most players are pretty good about knowing when to chatter. Once the play starts, there is no talk. Of course, if there’s a base stealer at the bag, the first baseman might want to chitchat a bit more to try to distract the runner.

The most difficult play for a first baseman is probably the 3–6–3 double play. In that play he begins by fielding the ground ball. Then he’s got to line himself up with the shortstop so he doesn’t drill the runner in the back with his throw. The shortstop has to get in position where the first baseman can see him.

Then the first baseman has to get back to the bag, and while he’s on the run, watch for a seed— a bullet—coming from the shortstop back to first base. Sometimes he’s fighting with the pitcher who is also coming over to cover first base.

I say that the ball coming across the diamond is a seed because the shortstop has got to fire that ball back to first base to try to get the runner coming from home plate. When infielders make that play, it looks so nice.

The best I saw at the 3–6–3 was Don Mattingly. Keith Hernandez was also very good and so was George Scott. This play requires quick feet; it is a complicated process and a lot of things have to go right.

The other difficult play is bunt coverage, which is especially tough for right-handed first basemen because they’ve got to spin to make a throw to second or third base. Getting the lead runner on a bunt is a critical part of the game. Having the ability to scoop up a bunt and make a quick release and a strong throw to second base to get the lead runner is huge.

Most pickoff plays at first base are pretty routine. There may be a signal exchanged between the pitcher or catcher and the first baseman, or the pitcher may just throw over there on his own. If the first baseman is holding the runner on base, he’s already in position to take a throw.

If there’s a concern that the batter may bunt, the first baseman may signal the pitcher to indicate to him that he plans to leave the bag toward second and break in toward the plate.

The first baseman also has to be ready to take a pickoff throw from the catcher. This play is often tried when there is a left-handed hitter at the plate, even though the batter stands between the plate and first base, making it more difficult for the catcher to make a snap throw. At the same time, though, the runner’s view of the catcher is blocked by the batter at the plate. The catcher will throw behind the batter.

The first baseman tries to make a swipe tag, catching the ball and bringing it down on the runner in one motion. You’ll see good base runners dive to the outfield side of the bag to require a longer tag.

Whether the pitcher makes a pickoff attempt or not, it’s important for the first baseman to get off the bag, giving him more range to field a batted ball. He doesn’t have to use a crossover step to get into position to make the play; he’s already there.

A few years ago, the Mets used a play with left-handed pitchers: The first baseman would play off the bag, and then he would break to the bag to receive the ball. It was a little confusing for a base runner because his view of the pitcher was blocked by the first baseman. Today many teams use this play.