C H A P T E R F O U R T E E N

After the catcher, the shortstop has the most demanding position because he is involved in so much of the game. The shortstop typically has the most total chances in the infield—other than the first baseman—and the greatest number of assists. And then there are throws from the catcher, relays from the outfield, slow rollers in the infield, off-balance plays, and so much more.

Shortstops need a strong arm or a quick release or both. And they need a lot of range.

I’ve already noted how Cal Ripken didn’t have great quickness, but he knew how to get in the proper position, knew his pitchers, and knew the hitters. That increased his range tremendously. If you understood the inside game of baseball, you could watch him from the stands and pretty much call every pitch.

The amazing thing about Ripken was that he played 2,632 games in a row, most of them at shortstop. That position is so demanding, and there is a lot of contact on double plays. How did he manage not to get cut or hurt with ordinary injuries that would keep him out of the lineup for a few days?

But shortstop lends itself to great athletes and awe-inspiring plays: Think of Derek Jeter diving head-first into the leftfield seats in July 2004, saving the game for the Yankees and leading to a painful twelfth-inning Red Sox defeat. (But 2004 worked out all right in the end . . . )

The shortstop is in some ways the captain of the infield. To begin with he has to coordinate with the second baseman on coverage. The shortstop also gets involved in relay plays, most of the time as the lead man because he should have the better arm.

Like the second baseman, the shortstop can usually see the catcher flash his signs to the pitcher and learn what the next pitch will be. Many third basemen want to know what the pitcher is going to throw, so the shortstop signals if it’s a fastball, a breaking ball, or whatever.

The signal to third base could be just a whistle, or it could be calling his name. If it is going to be a fastball, he might not say anything. Of course, he’s got to mix it up so the third base coach or the hitter doesn’t pick up on the signal.

A manager may have to decide between a power-hitting shortstop who is an adequate fielder and a superb fielder who is batting .220. A team can’t put an inadequate fielder at shortstop because it would hurt too much; the manager would probably try to find another position for him like first base or the outfield.

Look at the shortstops playing today; these guys are remarkable. When I played second base, shortstops were usually the smallest guys on the field. They were quick, and they weren’t expected to hit for power.

Remy Says: Watch This

Watching Infielders Adjust

If there’s a right-handed hitter at the plate and you see the shortstop take a step left toward second base as the pitcher goes into his delivery, you can expect to see a fastball or something hard and away—a pitch that a right-handed batter would tend to hit to the opposite field or at least more to the right than he usually does.

In that same situation, if he moved to his right toward third base, you could guess it was going to be an off-speed pitch.

With a left-hander at the plate, if he moved to his left, it would probably be something off-speed like a curveball, slider, split-fingered fastball, or a changeup. If the shortstop stays where he is, it’s probably going to be a fastball.

“Remy is genuine; there’s no phoniness about the way he presents himself. Of all the people I know in broadcasting, he is the biggest creature of habit in the way he prepares for a game; that’s the way the best players are, too.”

SEAN MCDONOUGH, FORMER RED SOX PLAY-BY-PLAY BROADCASTER

Ripken was the first big shortstop I remember; he was 6’4”. Derek Jeter, one of the more athletic shortstops in the game, is 6’3”.

They remind me of linebackers in football. They’re huge, but they’re also fast and agile.

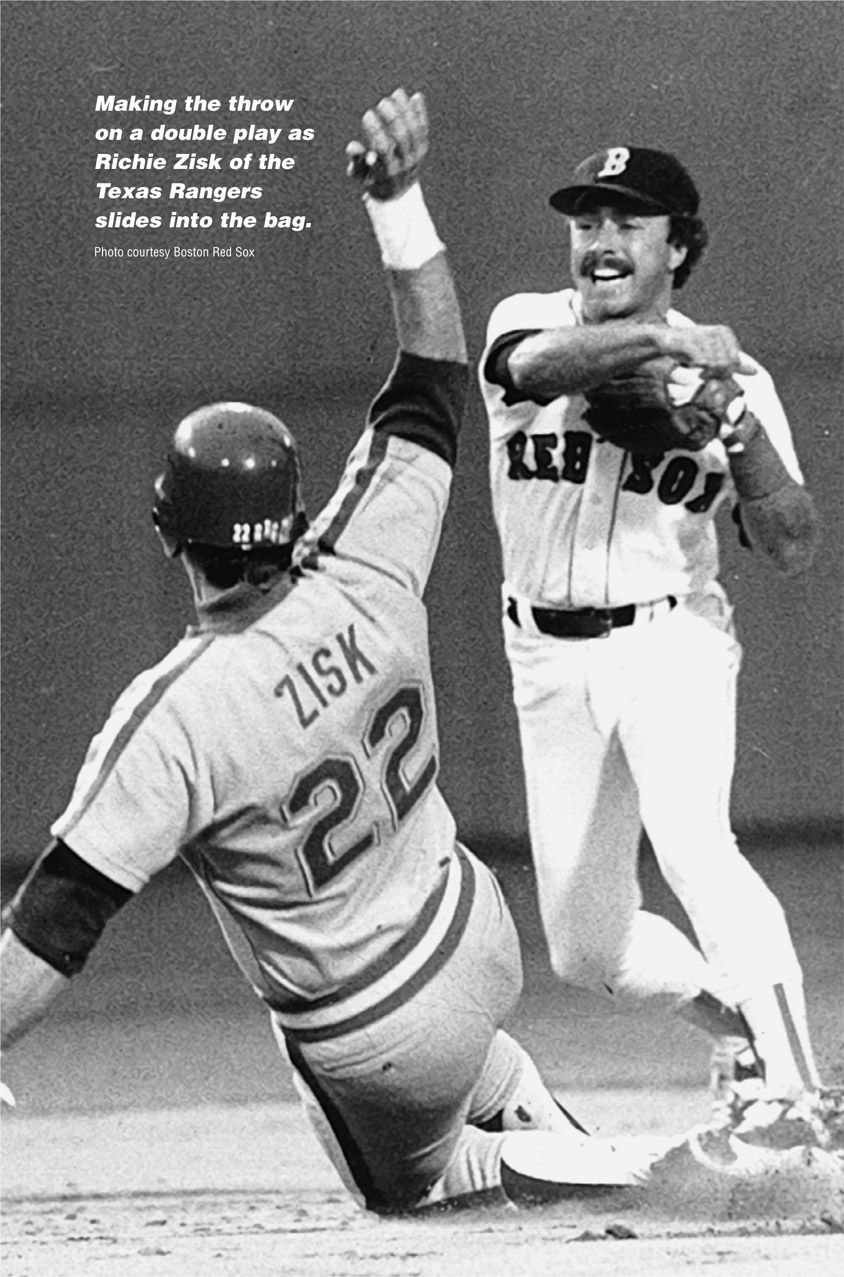

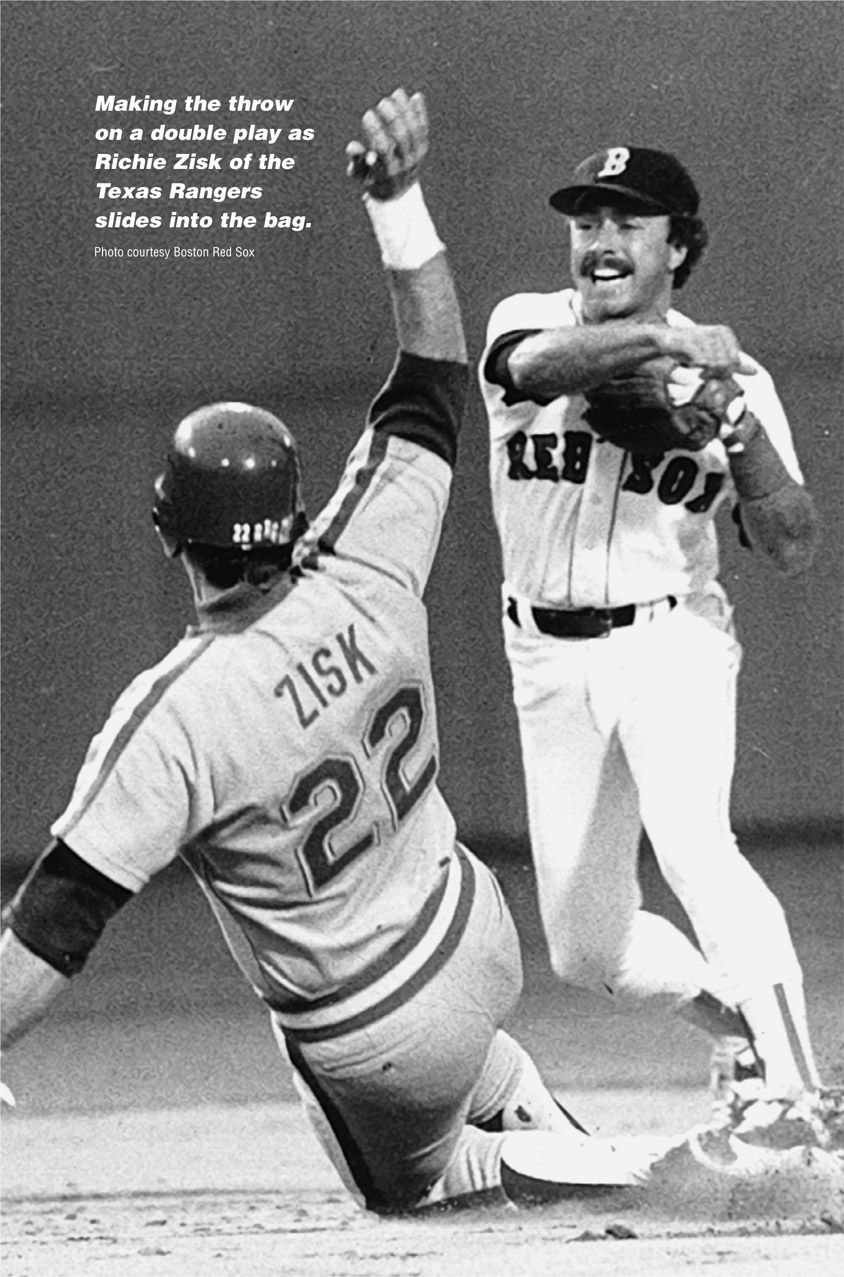

When it comes to the double play, the shortstop has the advantage over the second baseman; the play is in front of him and he can see where the runner is. Because of this, the shortstop knows exactly how much time he has and is in a better position to field the ball or take a throw, then get out of the way of the guy sliding into second base.

The most difficult play for a shortstop is going deep in the hole toward third base to make a backhand catch, then throwing a strike to first base. As a fan you look for a guy with arm strength and range. Can he get to the ball? And once he gets to it, what can he do with it?

I saw Garciaparra make that backhand play a thousand times; he’d grab the ball on the run, continue on toward third base, make an off-balance throw without planting his feet, and still reach first base with the throw.

Nomar’s style excited the crowd more than the conventional play. When he let the ball go, everybody followed the ball to first base; if you looked back at him, you’d see him over near the stands at third base. No Little League coach would ever had advised someone to play like Garciaparra.