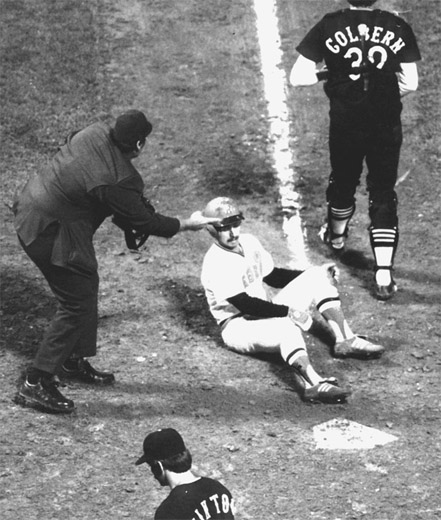

I’m tagged out short of the plate by Mike Colbern of the White Sox.

Photo courtesy Boston Red Sox

C H A P T E R S I X T E E N

The pitcher shouldn’t be a front-row spectator on plays in the infield. A Gold Glove pitcher gets into good fielding position after he delivers to the plate and can snare a ball hit back up the middle, pick up a bunt near the mound, and make a good throw to a base. A pitcher’s ability to make a play on a grounder or a bunt and get that lead runner can make the difference in a close game.

That said, most pitchers are not good fielders; they put all of their effort into their windup and follow-through, which usually does not set them up to catch a rocket back at the mound. That’s why it’s so impressive to watch strong fielders like Mike Mussina, Tim Wakefield, or Greg Maddux.

I’ve been impressed with Daisuke Matsuzaka’s infield skills, as well. In Game 3 of the 2007 World Series, he gave up a leadoff single to former Seibu Lions teammate Kazuo Matsui. Matsui made it to second on a fielding error by J. D. Drew in right field. But Matsuzaka erased him from the base paths when he snagged a hard ground ball back to the mound and ran directly at Matsui, setting up a rundown play that traded the runner on second for a slower man on first (and an out).

Some pitchers have difficulty throwing to first base; over the years that has been a small flaw in the skill set of Roger Clemens. Other pitchers won’t even make a pickoff attempt because they can’t make the throw well. Once teams get a sniff of that, they just send the runner as soon as the pitcher moves.

There is no question that a lack of fielding skills can hurt, but how much time does a team put into trying to make a pitcher a better fielder? The answer is not a heck of a lot; the number one job is pitching, and everything else is secondary. A pitching coach is not going to change a pitcher’s follow-through for the purposes of improving his fielding. That’s the last thing he’d want to do.

When you’re watching a game, don’t always shift your attention from the pitcher to the batter when the ball is in the air. Instead, take a look at the pitcher’s follow-through: Does he finish squared up with home plate in a good fielding position that gives him a chance to make a play? Pitchers who fall off to one side are not going to have a chance at a ball back up the middle.

As it is at third base, most of the plays for the pitcher are like hockey goaltending: all reaction. But I think the real key is the ability to make plays on bunts. Does this pitcher have the ability to come off the mound, pick up the ball, make the right decision on the play, and get off a good, accurate throw? That’s what separates an average fielder from a good fielding pitcher.

Remy Says: Watch This

“I Got It”

When there’s a pop-up to the mound, most teams tell the pitcher to let one of the other infielders get the ball if he can. This has been a bugaboo of mine for years.

There are four infielders running up the mound and dancing around, everybody yelling, “I got it, I got it.”

Many pitchers are good at pop-ups; during batting practice they’re out shagging fly balls. If the pitcher is standing on the mound and there is a routine little pop-up, I say, let him catch it.

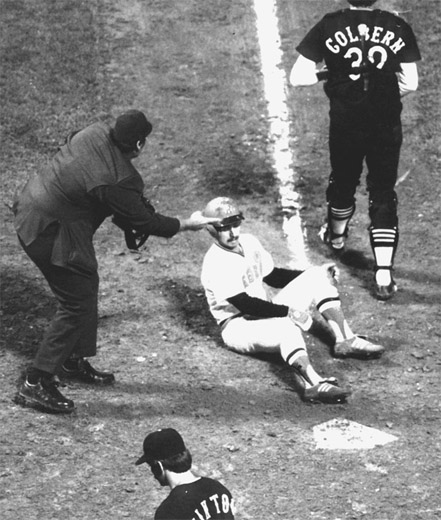

Curt Schilling pitched with power, finesse, and heart from the moment he arrived in 2004, and it is no coincidence that two new World Series trophies reside at Fenway.

Photo courtesy AP

Keep in mind that when a pitcher finishes his delivery, he may be just 52 feet away from the plate. I’ve seen some ugly scenes when a guy gets hit with a line drive back up the middle. It’s got to be a blur to a pitcher. All of a sudden, boom, he’s smoked.

One of the ugliest of all time was September 8, 2000, when Red Sox pitcher Bryce Florie was hit in the face by a line drive in the ninth inning of a game against the Yankees at Fenway Park. He suffered a terrible injury, but he had the guts to try a comeback in 2001. In the first game he pitched, somebody hit a line shot right back at him again. That’s got to make your legs shake.

When a pitcher or a batter gets hit in the head, he may tell the press, “No, no, I don’t think about it.” That’s baloney.

Another heart-stopper: a pitcher reaching for a line drive with his bare pitching hand. It’s just instinct. It’s a good thing most of the time he doesn’t touch the ball.

And sometimes you see some really wacky plays like the time El Duque—Orlando Hernandez, then of the Yankees—snagged a grounder back to the mound and couldn’t get the ball out of the glove. So he threw the glove to first base to get the out.

And Julian Tavárez, a Red Sox pitcher who seems to exist in a world of his own, made at least two throws to first base in the 2007 season that were bowled along the infield grass. I called it “Candlepins for Dollars.” Nothing personal; he got the outs.

On a routine pickoff play, it used to be that the pitcher was in charge and could throw over to first any time he felt like doing so. Nowadays, though, many pitchers take instructions from the dugout.

The pitcher might be instructed to take a step off the rubber, hold the ball, make a throw to first, or pitch out. The idea is to do anything possible to throw off the timing of the base runner. Some pitchers throw over to first just to buy time when they’re not yet ready to pitch to the batter.

With a runner on first and third, every once in a while you see the pitcher bluffing a throw to third and then spinning around to make a throw to first. I don’t think many pitchers use it at the right time. A good time to try it is with a 3–2 count and one out. The runner on first is probably going to be stealing.

The play very seldom succeeds, but when it does, fans or coaches might say, “How could that ever work?” It is such an ugly looking play and it is so obvious. But it occasionally works. I am living proof of that.

My very first game in the major leagues was April 7, 1975, at Anaheim. Before the game we had a meeting and we discussed the Kansas City pitcher, Steve Busby. One of the coaches said, “If there are runners on first and third, look out, because he fakes to third and throws to first, and he’s good at it.”

In my first time up to bat, I got a hit: a single to left field. I drove in Joe Lahoud for my first RBI and moved Dave Chalk over to third. Sure enough, I took my lead off first base and Busby faked to third, then spun and picked me off first base.

Dick Williams was the manager, and he told me to come sit right next to him in the dugout. He said, “Welcome to the Big Leagues. If I see that again, you’re going back to Salt Lake.”

The next time I was on first base with a runner on third, I took a lead of about 6 inches.