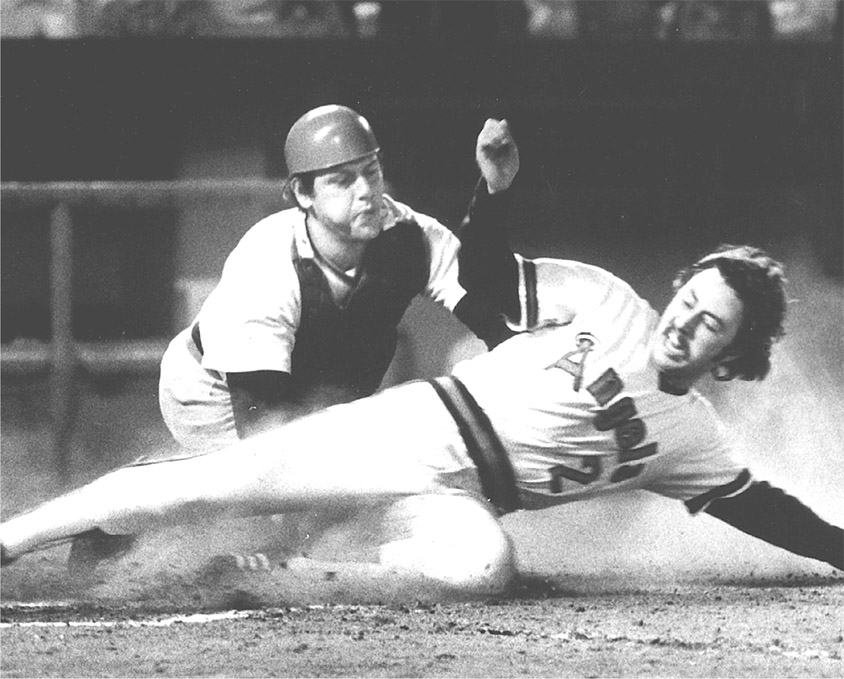

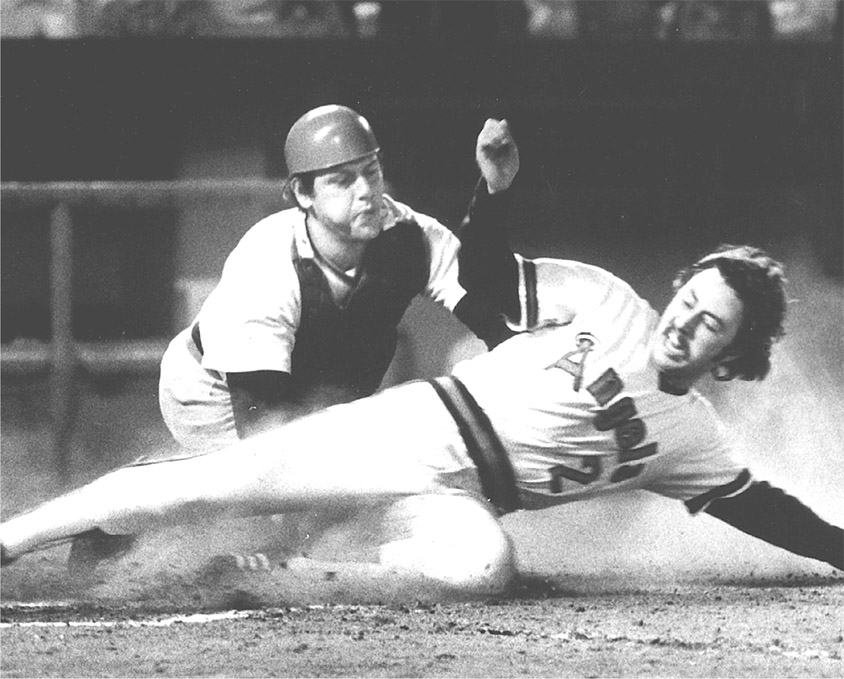

It was a thrill for me to play against the Red Sox. Here I am sliding in on the first-base side of the plate to avoid catcher Carlton Fisk, who was coming in from foul territory. Fisk later became a good friend of mine when I came over to Boston. The slide is not textbook—my hand is dragging, for one thing—but that happens when you’re keeping away from a tag.

Photo courtesy Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim Baseball Club

C H A P T E R S E V E N T E E N

Catching is the most physically and mentally demanding job on the team.

Baseball players are pretty set in their ways. Most of them get to the park the same time every day, get themselves ready for the game, take batting practice, and do their infield or outfield practice. Catchers do the same—and they have to go to school every day.

As part of his job, the catcher has to sit down with the pitcher and the pitching coach and perhaps the manager and go over the other team’s lineup, plus the players they’ve got on the bench as pinch hitters and pinch runners.

A good scouting report tells who is hitting the ball where. A team wants to learn as much as possible about its opponent’s usual strategies. When do they hit-and-run? What are the changes since the last game between the two teams? To this an experienced catcher adds the knowledge he has of the other team and its pitcher.

Alas, today’s game places more emphasis on offense than defense. Many defensive stars don’t get proper recognition. They may get it from their own managers, pitchers, and their teammates but not from the fans. Look at the catchers you see in the All-Star Game; they are all players known for their offensive abilities.

There used to be a stereotype about catchers being a bit dim, wearing the “tools of ignorance.” That is simply not true. Actually, most catchers are very intelligent and are much more involved with strategy and execution than any of the other players on the field.

Catchers can have all kinds of temperaments and personalities. Some are really intense and others soft-spoken and calm. But the one thing they have in common is that they are tough.

Catchers are constantly getting beat up. They take pitches off the fingers, chest, shoulders, knees, feet, or shins. Runners come barreling toward them at full speed, and they’ve got to stick a leg out to try to block the plate.

I know more than a little bit about bad knees with my own history. I can’t imagine being up and down on your knees like a catcher for an entire game. But there are guys who have played an entire career with bad knees and knee injuries. Carlton Fisk, the great catcher for the Red Sox and later the White Sox, had a career-threatening injury early in his career and went on to play for twenty-four seasons, until he was forty-five years old.

The pitcher and catcher would be in perfect sync if they agreed on every pitch before it was thrown. The less often you see the pitcher shaking off a sign and the fewer trips the catcher makes to the mound, the better the relationship. When the pitcher and the catcher are thinking along the same lines, they have probably done their homework together. They also know which pitches are working within this particular game and which are not.

Some proven veteran pitchers want to be in full charge. Nolan Ryan used to call his own game. But many younger pitchers won’t shake off a catcher, because the catcher is calling the game or because the pitch calls are coming from the bench. Coaches are not going to tell a rookie never to shake off the catcher, but if they start to see balls flying all over the place, the catcher is going to be put in charge very quickly. Coaches will tell the rookie: “We know better than you how to get this guy out.”

Midway through the 2003 season, I observed something I had never seen in uncounted thousands of baseball games: Red Sox reliever Todd Jones, recently arrived from Colorado, was on the mound in the eighth inning of a one-run game against the Blue Jays. Jones stepped off the rubber, walked behind the mound, and pulled out a little piece of paper.

“The wind always seems to blow against catchers when they are running.”

YOGI BERRA

At first I worried it was sandpaper, but no pitcher would be that obvious. It turned out that it was notes from the scouting report. It must have worked because Jones pitched very effectively, and the Red Sox went on to tie the game in the ninth and win in the tenth. I wonder if it’s just a matter of time before players start carrying little computers with them to consult the game plan.

And Curt Schilling may go into retirement as one of the great pitchers in the game’s history, but he’ll probably always remember June 7, 2007, when he shook off Jason Varitek’s pitch call with two outs in the ninth inning . . . and a no-hitter an out away. Varitek called for a slider, but Schilling didn’t agree and instead threw a fastball to Shannon Stewart who singled into right field. “We get two outs, and I was sure, and I had a plan, and I shook Tek off,” Schilling told reporters after the game. “And I get a big ‘What if?’ for the rest of my life.”

It was the third one-hitter of Schilling’s career; as of the end of the 2007 season he had never thrown a no-no.

Throwing out a runner requires much more than just a strong arm. Catchers have to have good footwork, allowing them to get into a good position to throw.

Think about what the catcher has to do to make a throw: He has to catch the ball, line himself up with second base, transfer the ball from the catcher’s glove to his throwing hand, and then make the throw. You’ll see catchers working on their footwork all the time.

And then think about the guys who are able to throw from their knees and still get something on the throw to reach second. Try it yourself some time; that’s pretty difficult to do.

The key to success is not so much arm strength as it is quick feet, a quick transfer from the glove to the throwing arm, and accuracy. A catcher who has quick feet is generally going to have a quick release.

It used to be that catchers would call for a particular pitch when they expected the runner to try to steal. The old saying was that if you were hitting behind a guy who could steal, you were going. We don’t see as much of that anymore. It seems as if many managers today don’t particularly care about the running game. Their theory is: “Let’s just get the guy at the plate.”

Another reason this has changed is that the first two guys in the lineup used to be Punch-and-Judy guys who couldn’t launch a home run. Today the guys hitting first and second, and throughout the lineup, have good power. So a pitcher is not going to make it obvious that the next pitch is going to be a fastball; if he does, all of a sudden his team is losing baseballs over the wall.

Here is another place where the emphasis on offense and bigger and stronger players has changed pitching patterns in baseball. It used to be automatic: on a 3–1 count a hitter would see a fastball. That is not the case anymore. Today, there are situations where a batter has to think backwards: on a 3–1 count he may well see an off-speed pitch.

A good catcher always makes a tough pitch look good. Some guys are so smooth; the glove almost never moves. They will get the glove in the spot where they want the pitch to land—that’s framing the pitch—and they leave it there. We used to call Carlton Fisk “Magic” because he was so good with his hands.

Other guys jab at the ball. If the catcher snares the pitch with his glove moving out of the strike zone—even if the ball is over the plate—the umpire may call it a ball.

If you see a catcher set up outside, you—and the umpire—expect an outside pitch. If the ball ends up going inside, the catcher will reach across to backhand it. The ball may still be on the corner of the plate but the pitcher won’t get that call.

There’s no certain way to catch the knuckler. I think Bob Uecker had it right when he said the best way to catch a knuckleball is to wait until it stops rolling and pick it up.

If you watch a good knuckleball pitcher like Tim Wakefield, you can’t tell from one pitch to the other where the ball is going. The pitcher doesn’t know, either. And so, how can the catcher prepare to catch something when he has no idea if it is going to dip, go inside, go outside, or rise?

Catchers try not to reach for a knuckleball. They keep the glove back and hope the ball finds the glove. Some catchers use an oversized glove when they’re working with a knuckleballer. But then you see some catchers who can’t get the ball out of that big glove to make a throw to second base.

Anytime a knuckleball pitcher is throwing, players who can run—and even those who can’t run very well—want to steal a base. They figure it is fifty-fifty whether the catcher is going to catch the ball.

On defense, when a knuckleball pitcher is on the mound most fielders play everybody to pull because it is a very slow pitch and most batters are going to swing early. With a righty at bat, fielders will take a step or two to their right; against a lefty, they’ll move to the left. You almost never see fielders expecting the batter to go the other way. It’s just not going to happen.

Some catchers maintain a constant stream of chatter. There are guys who jabber all the time, and there are guys who don’t say a word. Thurman Munson of the Yankees was always trying to distract hitters at the plate.

I remember once when Carl Yastrzemski stepped out of the box to tell a catcher to shut up.

The relationship between a catcher and an umpire is interesting; the catcher is always trying to get more for his pitcher. If he is not getting strikes on the outside of the plate, he is going to ask the ump why, and try to talk him into those pitches as the game goes on.

There are a lot of arguments that the fans don’t see; there’s an unwritten rule that the catcher doesn’t take off his mask and turn around to argue with the umpire.

There are ways to communicate with umpires without embarrassing them; that’s what most catchers try to do unless they are completely ticked off. That’s not to say that there aren’t days when the umpire might miss two or three calls in a row and the dugout starts giving it to him and the catcher gets involved.

The tough part comes when a catcher comes up to hit. If the catcher doesn’t like a strike call, he might just bite his tongue. Or he will say, “Give my guy that pitch, too.”

Although the catcher and starting pitcher usually have a plan for each batter before the game begins, in most situations the catcher calls each pitch by signaling from his position behind the plate. The basic set of signs is: one finger for a fastball, two for a curve, three for a slider, and four fingers or a wiggle for a changeup.

The catcher will change the signs when there is a runner on second base who might be able to see them and send a signal back to the batter.

He may use an indicator. For example, the indicator may be two fingers, and thus the pitch call will be the next sign after the catcher flashes two. He might send three, one, two, one, three; the sign after the indicator is one, which means fastball.

Television is a factor here, too. Players can go in the clubhouse and watch the game and they will be able to see if the catcher is using the same sequence all the time. There are some ballparks where the guy running the first-base camera will be in the dugout or nearby. There were managers who used to watch the little monitor on the camera; it was up to the umpire to see that, and if he did, he would get the monitor out of there.

Everywhere players go, there are rumors about one team or another stealing signs over television, with binoculars, or a telephoto lens. I don’t know whether they are true or not.

I can tell you this, though: when a good pitcher is getting lit up, the coaches are going to try and find some reason. They might say he is tipping his pitches—doing something to give away the type of pitch he is about to throw. Or they might say the other side is stealing signs.

Years ago there was a rumor going around about a little box out near the bull pen in Yankee Stadium where the coaches could watch the game. It was just off-center from home plate, and the rumor started that these guys were stealing signs. Who knows?

When I played, we would go into Milwaukee and they would pound the heck out of us, and we were totally convinced somebody was stealing signs from the outfield.

There are some batters who try to peek back at the catcher when they are up at the plate. I got caught doing it against Texas. Jim Sundberg was the catcher, and I had some pretty good success for a while just kind of glancing back. I wasn’t really looking for the sign; what I was trying to see was how he set up. You can pretty much tell the location of the pitch from that. So I did it, and Sundberg saw me, and he said, “Peekaboo.”

I got the message right away and that put an end to it. The message was: “If you keep doing it, you are going to get drilled.”

In some parks at certain times of the day the hitter can see the shadow of the catcher out in front of home plate and he can see that shadow move outside or inside. In any case, that’s why you’ll see a lot of catchers switch location late, just before the pitch. They might start by setting up outside and then move inside. The catcher will also do this when there is a runner on second base, because many try to steal signs or location. The later he moves, the tougher it is to figure the location.

The rules say the catcher is not supposed to block home plate unless he has the ball in his glove. But that’s almost never enforced; you’ll regularly see the catcher with a foot out in front of the plate as he is reaching to get the ball.

What a catcher tries to do is get his foot on the third base line in front of home plate so that his knee is squared up with the incoming runner. He doesn’t want to be caught opened up, or with his leg out to the side where a collision is going to blow out his knee.

Jason Varitek of the Red Sox is one of the best at blocking home plate. He is fearless. He will put anything out there: his knee, his foot. Of course it all starts way before the play; Varitek is as well prepared as any catcher in the game and tough as nails. If I wanted to show a young player how to go about his business, he’s the one I’d point to.

In today’s game we see more guys knocking catchers down than we did in the past. There seems to be less sliding at home plate and more collisions than I can ever remember.

Why? Because catchers are blocking the plate better. They are standing in front of home plate and the runner sometimes has no choice but to try to knock them over and kick the ball out of their glove or just knock them off the plate.

One of the most awful things to see is a headfirst slide into home plate. It’s just a no-no.

Look at all the equipment the catcher is wearing: on his shins, his chest, his glove, and his head. He’s like a knight in armor. In a collision he may fall on the runner or reach for a throw and come back and dive on him. Fingers and hands don’t hold up well in those situations; just ask Manny Ramírez.

Then again, if a runner is coming in and sees the catcher reaching up the first base line for the ball and the plate is open . . . aw, forget it. My rule of thumb, if you’ll pardon the pun, is: You generally don’t come out well in a headfirst slide into home.

When you’re watching from the stands and a play is developing at the plate, try to sneak a peek at the on-deck batter. His job is to get into a position that allows the runner coming from third base to see him. The on-deck batter is supposed to look for the throw, and tell the runner whether to slide or come in standing up.

If he wants the runner to slide, he’ll be waving his arms down. If he puts his arms up, the runner can relax a bit and come in standing up because it is not going to be a close play.

The slide should be automatic unless the on-deck batter signals to stand up. Sometimes it gets messed up, and the on-deck batter doesn’t get in position. The runner doesn’t see the signal and ends up standing up at home plate when he shouldn’t be.

The on-deck batter may also signal on which side to slide, but that’s something the runner should be able to pick up by looking at the position of the catcher as he is coming in.

I guess I know as much as anybody about sliding into home plate. I learned it on Sunday, July 1, 1979, the Red Sox against New York at Yankee Stadium, in front of 51,246 fans.

It was the first inning and I led off the game with a triple to centerfield. Rick Burleson was up next and he hit a pop-up down the first-base line. I can’t tell you today if the third-base coach said to stay or go, but I made my own mind up to go. I thought first baseman Chris Chambliss was going to make the catch over his shoulder. Instead second baseman Willie Randolph made the catch coming in.

There were no outs, and I shouldn’t have been going anyway, because with nobody out you’ve got to be 100 percent sure you can score. I think being in Yankee Stadium, I was a little juiced up in the first inning.

I was out by 10 feet. I went into this little hook slide and caught a spike. Jim Rice carried me off the field. That was the start of my knee problems.