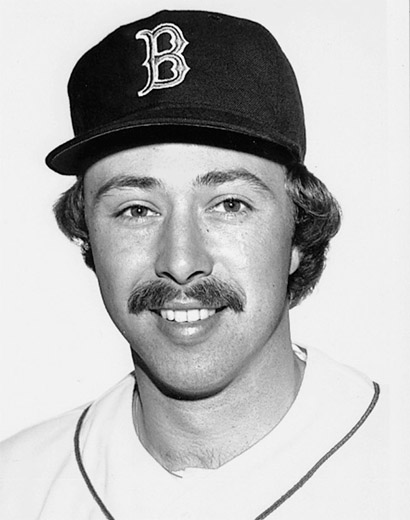

Happy to join the Red Sox in 1978.

Photo courtesy Boston Red Sox

C H A P T E R T W E N T Y - O N E

We’ve all gone to a Little League game and seen the center fielder watching an airplane fly overhead or a third baseman with his fielder’s mitt on his head instead of his hand. That doesn’t happen in the major leagues, of course, but even pro ballplayers are not perfect. Every player’s mind wanders sometimes. It’s a mentally draining game.

In the major leagues teams play 162 games a year. There are times when a player is just not into it, and that’s generally when he gets smoked. A lot depends on how the team is playing, how his own game is going, how fatigued he is, and whether he is sick or hurt.

We look at the players on the field as if they are robots. What you don’t see from the stands is that one player has a tight hamstring. Another has a tender elbow. And another has something bad going on at home.

When fatigue sets in, the concentration level goes down. Players may have a Sunday afternoon game in Kansas City or Texas in ninety-degree heat and 90 percent humidity or thirty-five degrees and a cold drizzle in Boston in April. When you’re focused on how poorly you feel, you don’t play as well.

In June 2002 Casey Fossum was pitching in relief for the Red Sox against the Yankees. It was the bottom of the ninth, and the Sox held a lead right there in the home of the enemy. The Yankees had runners on first and second with just one out. Fossum was pitching to pinch hitter Shane Spencer, and he hit a comebacker to the mound. Fossum caught the ground ball and threw to the plate. Unfortunately there was no runner coming home. But catcher Doug Mirabelli had the presence of mind to throw from the plate to first base, and they caught Spencer anyway.

Rem Dawg Remembers

The Internal Dialog of a Hitter

The mental part of hitting can drive someone crazy; watching from the stands you have no idea what these guys are going through.

The internal dialog is constant with every pitch. We may talk about it during the broadcast, or the scoreboard may tell you that this guy hasn’t had a hit in his last twenty at bats; trust me, he knows all about it.

Every time a slumping batter goes to the plate, it feels like he hasn’t had a hit in three weeks, even though it has only been a couple of days. Ballplayers also talk to themselves throughout the game. “I’m 0 for 2 now, I’ve got to have a hit here to go 1 for 3, and then if I can get another one, I’ll be 2 for 4, which is a great night.”

Believe me: Hitters have many, many sleepless nights.

Fossum was an example of a guy losing touch with the situation at that moment. For some reason he thought there was a man on third. The thing that amazed me was that Mirabelli was paying attention; it was a good thing he was watching, or he would have gotten the ball right between the eyes.

One of the more famous meltdowns in recent years was that of Rick Ankiel, a left-handed pitcher for the St. Louis Cardinals, who was a phenomenon in his first year in the majors in 2000. He had an 11–7 record during the season and then in the playoffs against Atlanta, he suddenly couldn’t find the plate with a map. His pitches were out of the strike zone by yards, sometimes going right over the batter, the catcher, and the umpire.

That was so sad to watch. Here was a kid with a great arm, and then you’re watching the nightly sports highlights and they’re showing him banging pitches off the backstop.

I’m sure a lot of the problem was psychological. Once something bad happens, if you get it in your mind that it’s going to continue to happen again, it’s going to happen. After returning to the minors for a season, Ankiel made an unsuccessful comeback at the end of the 2004 season before leaving the pitcher’s mound and trying to recast himself as an outfielder. He returned to the major leagues in August of 2007 and posted a .285 batting average with 11 home runs in the last third of the season.

Remy Says: Watch This

Keep Your Eye on A-Rod

It’s not fair to lay the Yankee’s troubles in the 2007 postseason on Alex Rodriguez. He may be the greatest player in the game, but unfortunately the postseason has yet to work out for him in New York.

During the season A-Rod seemed so fluid and smooth when things were going well. And then in the playoffs you could see him pressing with a very mechanical swing. When you press, I don’t care how great you are, you are not going to be as good.

To many of the fans in New York, the only way he can earn his Yankee pinstripes would be to not only win a world championship but to be a major part of it. (This is a guy who is probably going to break Barry Bonds’s home run record if he can stay healthy.)

After the 2007 season, it looked like he was going to be leaving New York, and if he had, he would have been remembered as a great player who never won a championship. Now A-Rod and the Yankee ownership have kissed and made up, and so we’ll see how he performs in years to come.

I thought his agent’s activities, coming out with the news about A-Rod’s contract plans in the middle of Game 4 of the World Series, were disgusting. It was pathetic to see him try to make one of his clients bigger than the game at a time when all the focus should have been on the Colorado Rockies and the Boston Red Sox.

Sometimes these guys get so powerful that they think that they just control everything. It was poor timing and bad taste. Had he been my agent, I would have been pissed off at him because his actions made his client look stupid.

Rain delays are the worst baseball “events” possible. I have already said how important it is for ballplayers to get into a comfortable routine. Anything that interrupts the routine throws the whole day out of whack.

If the delay comes at the beginning of the game, the players have done all their work to get ready to play and all of a sudden they are put on hold. It’s especially bad to have the starting pitcher loosen up and then not be able to start the game.

A rain delay in the middle of the game is another kind of disaster. You are in the flow of the game and all of a sudden it is stopped and you have no idea how long the delay will be. Let’s say one of the team’s best pitchers started the game. After a delay of an hour and a half, does it make sense for this pitcher to go back out there again? He runs the risk of injury or a bad performance—at best, it’s a wasted start.

Some managers have chosen not to start their best pitcher in a game when there is a good chance the game will be interrupted by rain. They might start a relief pitcher, and once the rain delay is done, bring in a starting pitcher.

When the rain comes, players head up to the clubhouse; some play cards or watch TV. It is hard to keep a mental edge. When the grounds crew takes the tarp off the field, they’ve got to get themselves back in gear.

I have come to the conclusion that every ballpark should be built like Safeco Field, with a retractable roof. There are no rain delays there, even though it rains a lot in Seattle. You know when you start the game, you are going to be playing at least nine. Even when the roof is closed, it is a beautiful place; the roof covers the field, but you can still see a piece of sky.

Nobody likes a rain delay except the hot dog and beer vendors.

I hate extra innings. I never liked them as a player, and I like them less as an announcer.

Baseball strategy is built around the nine-inning game, and it can really mess up your plans to go deep into extra innings. Strange things happen in extra innings; it seems like everybody is trying to end it with one swing, and it doesn’t usually work out that way.

Remy Says: Watch This

If I Were Commissioner . . .

If they made me commissioner of baseball, I would want to find ways to speed up the game. There is no clock in baseball, which is a great thing, but some games go on and on. It’s ridiculous.

Get pitchers to stay on the mound and throw the ball. Don’t let hitters leave the batter’s box.

Why should a pitching coach be allowed to go out to the mound? Would the hitting coach come out in the middle of an at bat and talk to the batter? No. Would an infield coach go over to chat? No.

I watch the 1978 Red Sox–Yankees playoff game when they show it every once in a while. Ron Guidry gets the ball and he’s on the rubber ready to go. Batters never left the box.

TV has something to do with it, with commercial breaks. But if I were commissioner, I would get them out there to make them pitch and make them hit.

I think the idea of instant replay is a good one. In some parks it is tough to make some calls. The umpires are making calls about whether a ball is fair or foul or home runs looking up from the field. That’s tough. When we look at the replays, we’re looking down from above, and we can slow things down and look at them in detail.

They should have an umpire somewhere with a monitor. When it is necessary, he makes the call. I think it is only fair.

The more I see interleague play the less I like it. It is boring to me. But fans apparently like it, so it is not going to go away.

The other thing that bothers me is having two sets of rules. In the World Series, Colorado came to Boston with their team set up with a bunch of versatile bench players but no regular designated hitter.

They put up a guy as DH and he batted ninth, striking out four times in the game. And then when Boston went to Colorado, they had to sit down one of their better hitters and fielders, Kevin Youkilis, so that they could put David Ortiz into the lineup. So it is not fair for either team.

And again I don’t find anything interesting about watching the pitcher hit, even when Daisuke Matsuzaka got an RBI hit in the third game of the World Series.

Good for him. I still don’t like it.

It is mentally and physically draining to play all those innings. On the bench everyone is wondering when the heck somebody will win this thing. It is almost like they are caught by surprise when they do win.

The manager has already played out his plans for a nine-inning game. Extra-inning games can tear down the pitching staff. The manager may have to use a pitcher he wanted to rest, or he might end up using a pitcher for two or three innings when that pitcher is not used to going that long. As a result the team may lose that pitcher for two or three days.

If you look at the bench, it is not always full because a lot of guys are out of the game and have already made their way into the clubhouse. Teams have different rules; some managers let them go in and some don’t.

Extra innings also means it becomes a one-run game. If a power hitter is up, everyone is hoping for a home run. If a team gets a man on first, they are probably going to try to bunt him to second. I have seen guys bunt with one out to get a man into scoring position, something you wouldn’t ordinarily do.

If the game is at home, it becomes a sudden death situation: one run and it’s over. Teams even get that feeling on the road: “If we can score one run, we’ve got a shot.” But when a team gets the lead on the road, there’s another problem. In most cases the best pitchers have already been in the game, so the manager may have to try to protect a one-run lead with a guy who wouldn’t normally be used in that situation.

Remy Says: Watch This

The Day After the Night Before

As a fan, when you leave the ballpark or turn off the TV at 11:00 p.m., you go home and to bed. But a ballplayer may have physical therapy or other things he needs to do after a game, and it may be midnight or later before he heads home, and then he’s still wired. Some guys eat; some stay up watching TV. They may go to bed at 2:00 a.m. and sleep until 10:00 or 11:00 the next morning.

Some managers call off batting practice on a day game, or hitting might be optional. You may not see all of the star players in the lineup because a day game after a night game is the perfect time to give guys a day off. Often the catcher who worked the night before gets to rest.

But when it’s crunch time in a tight pennant race, you can expect that all the regulars are on deck.

Players and managers sometimes look with dismay at the upcoming schedule, especially when it includes cross-country trips. There are some road trips that are sure to be tough, with a lot of travel and crazy hours.

In recent years I’ve seen horrors like this: a night game in Anaheim followed by a flight to Texas for a game the next day. The team loses two hours on the clock as it heads east, getting to the hotel as the sun comes up. USA Today is outside the door when the players check into their hotel rooms. After a few hours of fitful sleep, it’s off to the ballpark.

Most teams will send the next day’s starting pitcher on ahead so that he will get a good night’s rest. If they are going to get in at four in the morning, the pitcher is not going to be with them. That way they’ll have at least one rested person on the diamond.

One time while I was with the Angels, sending the pitcher ahead didn’t help. We were coming from California to New York, and when we got to the hotel, the pitcher who had been sent on ahead was coming in from a night on the town. That didn’t go over very well.

How can players communicate with each other when there’s a wave of noise coming from the stands? The truth is, they don’t really hear it. It’s crazy, but they are so focused on what they are trying to do that it becomes a buzz. Can it become a problem on a pop-up? Sure it can. One fielder calls for the ball and the other doesn’t hear him. They’ve both got to concentrate. But as far as what they’ve got to do as fielders, and what their responsibilities are on plays, I don’t think the crowd has any effect on that at all.

A good ballplayer can communicate pretty well in any situation. It’s like taking signs from the third-base coach. The player should never miss them because he should always know what to look for in a particular situation. For example, if there is a man on first, the batter should be looking for the hit-and-run or the bunt. He’s not looking for the squeeze. So he shouldn’t miss the sign.

It’s the same idea for players on defense. Do they have mental lapses? Sure. But a good player is thinking before the play: “Okay, we’ve got runners on first and second. The batter could bunt or he could swing away. Here’s where I’m going to play and what I’m going to be prepared to do.”

On some teams the fielder might look to the dugout, and a coach there would let him know where he should move or what play is on.

I like to watch players’ reactions. That said, you can’t always tell how a player is going to behave when he gets back to the dugout. There are certain guys who never change the way they act; they will be the same whether they got a hit or made an out. You will have other guys who just flip out, and you know they are going to be upset when they get back to the bench.

Instead of watching the next batter walk up to the plate, follow the last batter back to the dugout. If the guy is really pissed off, watch as he prances up and down the dugout. And if he does something really dumb, once he walks by, you’ll see other guys laughing at him.

You may also learn something by watching where the players sit. Some always seek out a particular seat in the dugout. You might see one guy who always sits at the end of the bench; that’s where he is most comfortable. Players not in the game that day are usually more relaxed and may sprawl on the steps.

When pitchers come off the mound, some will go to the far end of the dugout to be as far away as they can from the pitching coach or the manager, while other guys will go and sit right next to their coach and the catcher.

Catchers generally stay near the manager and coaches and are usually constantly discussing the game. Depending on what happened in the last half-inning, a coach might ask the catcher what pitch was thrown, why was it thrown to a particular location, or why the pitcher had shaken off a call.

I’d rather hear 35,000 happy, buzzing fans than be in front of 5,000 people after a rain delay, drunk and screaming at me after I’ve struck out. You can hear every one of them.

There may be some leather lung in the stands, and every time you move or do something wrong, this guy is all over you. You saw him last week, and he was doing the same thing. It gets personal sometimes. Ballplayers are not always the most mature people, and sometimes you say something back and it becomes ugly.

There were some places we would go to as players where the crowd was really raucous, like Yankee Stadium. Actually, it was fun to go to New York and have those people get on us. You don’t expect the people on the road to like you. You want them to get on you. At least you’re recognized.

It’s harder at home when people yell at you. This is your house; these are your fans. It takes a strong guy to ignore it. There are some guys who can’t adjust to it. I’ve known guys who were so intimidated at Fenway Park that they had a hard time playing there.

I hated it when my parents were at the ballpark. I knew they were in the family section, but I didn’t know who was five rows behind them. It could have been some jerk who just couldn’t stand me, and he was just going to eat me up the whole game.

Remy Says: Watch This

Standing at the Plate

If you are a guy who hits forty or fifty home runs a year, you’re allowed to stand at home plate and admire the flight of the ball. But some clown who hits four a year and flips the bat looks ridiculous. That’s the kind of stuff that drives me crazy.

Like Jim Brown used to say about celebrations after touchdowns: Act like you’ve been there before.

Or if I made an error, the next time I came to the plate, I would get booed, and nobody wants his family to hear that. I think the players’ wives become more immune to that because many of them are there all the time. They know it is part of the business.

And finally, there is nothing more embarrassing than making an error. Everybody is watching you, and you make a horrible play; it’s not a good feeling. I guess my all-time most embarrassing moment was when I made two errors on two consecutive balls while playing for Anaheim. Some friends of mine from Somerset had come out to California on a visit, and they had great seats in the front row.

There were back-to-back balls hit right to me, and they both went right between my legs. Even our own fans were booing me; they were all over me. I didn’t make another error for the rest of the day, but I knew I didn’t want another ball hit to me for a while.

It used to be that when someone hit a home run, he came across home plate, took congratulations from the guy on deck, and went into the dugout. That was it. No tipping the cap; no curtain call. Ballplayers rarely showed any emotion on the field; you didn’t see guys hit a home run and then pump their fist as they circled the bases.

One of the unwritten rules was to never show up the pitcher; players knew if they did, the next time they got up to the plate, they’d get drilled.

Players today show more emotion. It is not as splashy as basketball when a guy dunks, or the celebration in the end zone when a football player scores a touchdown. Traditionalists don’t like it. But baseball is entertainment, and people seem to like it.

When David Ortiz or Manny Ramírez launch one, they don’t show up the pitcher—but they do sometimes take a moment to admire their work. Lately, Manny has taken to holding up his arms like a football ref signaling a touchdown; it’s just Manny being . . . Manny.

And then there are players who operate on a completely different plane. From the day Rickey Henderson came into baseball, people called him a hot dog. He did everything with style. I am sure he took a lot of abuse for that early in his career. But Henderson acted the same throughout his whole career. That’s Rickey’s game, and unless he unretires again (and that’s not out of the realm of possibility), he will be eligible for election to the Hall of Fame in 2009 or 2010 and he’s going to get in.

Reggie Jackson was another example of a guy who was entertaining to watch. People loved to watch him swing; even when he missed it was exciting.

Another kind of hotdogging are stunts that seems to come up every ten years or so: Some outfielder comes in to pitch an inning or some player wants to get into his team’s record book by playing every position in a game or a season.

José Canseco, who was a bit flamboyant, almost ruined his career in 1993 when he was playing for the Texas Rangers against the Red Sox. Texas was getting creamed by Boston and they were out of relievers, so Canseco came in to pitch the ninth inning. He ended up tearing a ligament in his right elbow and a month later had to have surgery and was out for the rest of the season.

We know that even the best batters make an out somewhere between six and seven times out of every ten at bats. Some hitters just jog back to the dugout and take their seat; others may throw their helmet or commit assault and battery on the watercooler.

A batter gets upset when he strikes out by swinging at a bad pitch. The pitcher didn’t do it, and the fielders didn’t make a great play; he got himself out. It’s especially galling if he had a chance to drive in a run.

Looking at some players, you couldn’t tell whether they were 4 for 4 or 0 for 4 in a game with four strikeouts. That’s just their makeup. Freddie Lynn was a great player who was laid-back and relaxed; it’s the same thing with Manny Ramírez. On today’s Red Sox, you can watch the face of Kevin Youkilis to see how he feels about his last at bat. It would be nice to think that everybody remembers the baseball season is 162 games long, that an everyday player is going to get at least 500 at bats, and that athletes can take failure in stride. But for most players, it’s not that way; it’s life and death with every at bat.

Managers have to be careful in handling their players. Just because one player shows his emotions, that doesn’t mean he cares more than the other guy. It doesn’t take long for a manager to get to know his team. He sees them in battle every day and sees how they react to events.

Remy Says: Watch This

The Warning Sign

These days, after a retaliation, you’ll see the umpires warning both benches to put an end to this stuff. If the umpire feels a pitcher is purposely throwing at somebody after that, the player and his manager are tossed out of the game.

If you’re watching from the stands and you see the umpire hold up the game and point to both dugouts, that means they have been warned. What he is trying to do is take control of the situation before anything else develops. If there was an incident the day before, sometimes the umpires will warn the managers before the start of the next game.

As a manager or a teammate, it’s not a great idea to go up to some players and say, “How the hell could you swing at that pitch?” You might end up getting knocked out. You let a teammate cool off and talk to him later. But other guys don’t mind talking. Players on the bench might be in conversation with a teammate and talk in great detail about what the pitcher is throwing, and it will help them when they go up to bat themselves.

The same thing goes for hitting coaches. They’re not likely to go up to a batter immediately after the batter makes an out to remind him that he wasn’t supposed to swing at a certain pitch. They know that the player is not intentionally going after bad pitches. A good hitting coach has to know when to approach somebody and when to leave him alone.

Have you heard the line about a guy who goes to a boxing match and a hockey game breaks out? Brawls are pretty rare in baseball, but a few times each season something happens that pushes a team over the line.

When a pitcher starts head-hunting, you know something is going to happen. It often is a carryover from the night before. Let’s say a hitter had a great night the night before, going 4 for 4, with a couple of home runs. On his first time up the next game, the pitcher knocks him on his butt. That is probably going to draw a retaliation; his team’s pitcher will choose someone to knock down himself.

There also may be a personal thing between a hitter and a pitcher that could go back three years, and now it is the right time for the pitcher to drill him. Well, the hitter hasn’t forgotten, either, and that may cause a brawl.

And sometimes there are bad feelings that develop between teams, like the unpleasantness between the Red Sox and Tampa Bay a few years ago. Almost anything could set it off. A player may go into second base with cleats high, and other teammates will try to protect their second baseman or shortstop.

If a brawl happens, although it may look like mayhem on the field, there are usually only a few players fighting. There are always some clowns who come charging across the field from the bull pen because they think that is what is expected of them.

Sometimes in the middle of a brawl, other players go in to try to settle an old score with someone not involved in the original fight. They just take advantage of the craziness to get in a shove or a punch.

But most of the guys out there are just trying to keep other people from fighting. And if the star pitcher is involved, he may end up surrounded by teammates who are there to protect him. They are not going to let anybody get to him; he’s their bread and butter, and whether they think he is right or wrong, they are going to make it hard for the other team to get to him.

Like I said before, baseball is a game of habit. Players have the same routine every day: go to the park, take batting practice, take infield practice, and play the game. Somewhere along the way, habits can often become superstitions and compulsions.

Some players will take the same number of swings in batting practice and the same number of ground balls in infield practice. Some guys will run the bases; other guys won’t.

Then there’s the way they dress. Some players will always put on their right sock first, then their left, or the other way around. Or they will have a favorite uniform for batting practice and another for the game. They’ll have a special glove they use. Or they’ll insist on wearing a tattered old undershirt all season, or use a batting helmet cruddy with five seasons’ accumulation of pine tar.

Then again, if things go badly, they’ll switch anything and everything.

When I was going out to the field between innings, I used to have to touch second base. I don’t know why I did it, but it had to happen every time, and if somehow I forgot whether I had touched the base, I would run over and touch it again.

There are many players who don’t want to step on the line when they take the field and always jump over it. Other guys have to touch the line. Wade Boggs used to go out and run his sprints at 7:17 before a 7:30 game. Not earlier and not later. He would eat chicken for lunch every day.

I have long worried that when some players get out of the game, they’re going to have to get treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorders, because without baseball they’ll have to find something in the house they’ve got to do every day.

In May 1976, I was on the other side of a pitching gem. I broke up a no-hitter by Ken Brett of the Chicago White Sox in the ninth inning with two outs. I checked my swing and ended up hitting a slow roller down the third-base line. Jorge Orta put his glove down, but the ball went underneath.

I was stunned when I got to first base and saw that the official scorer had given me a hit. Usually, at that point in a no-hit game, whether it is the visitors or the home team, the scorer is going to give the pitcher the benefit of the doubt.

The score was 0–0 going into the tenth, and Brett came out to pitch that inning, too. I doubt that you’d see that today. He ended up winning the game in the eleventh inning with a two-hitter.

That said, when a player comes up to bat in the ninth inning and the other pitcher is throwing a no-hitter, the batter sure wants to break it up. He has been battling this guy all day, and he is 0 for 3. But you want a solid hit. I would never bunt in that situation to break it up. That would be bad form. But I also didn’t go to the official scorer and ask that my hit be scored as an error.

I kidded Brett about that game for years; sadly, he passed away in 2003 after losing a battle with brain cancer.

Rem Dawg Remembers

On the Bench and Field in a No-Hitter

One of the best-known superstitions in baseball comes when a pitcher has a no-hitter going. The players are supposed to leave him alone, or at least never mention the line score of the game.

As announcers, do we tell listeners? I think we have to. People are flipping around the dial and you want to hold them. The announcer could say, “The Angels don’t have a hit yet.” I don’t have a problem with just flat-out saying, “Clay Buchholz has a no-hitter through seven innings.” But in the dugout, when it gets to that point, you don’t mention it. The pitcher knows he has one going, but teammates don’t want to jinx him.

A no-hitter is one of the most difficult things to do in sports. Players want to make sure they handle everything cleanly; they don’t want to allow an extra guy to come to the plate by making an error. I was on the field behind Nolan Ryan when he threw one of his no-hitters, this one against Baltimore. I can’t say it was fun; it was a nerve-racking experience.

How much is too much? That was one of things that crossed more than a few minds on the night of June 27, 2003, when the Red Sox drubbed the Florida Marlins by a score of 25–8. In the first inning the Sox scored ten runs before the first out was recorded and fourteen before the third out was made on a close play at the plate.

Among the many great records of that day came when Johnny Damon got three hits in three at bats in that first inning.

But many in baseball were also unhappy later in the game when it seemed to them that the Red Sox were piling on extra runs. Here’s another of the unwritten rules of baseball: If you’re way out in front, you don’t steal bases, you don’t swing for the fences on 3–0 counts, and you don’t send the runner from third to home on a close play. The way I see it, if you’ve got to slide at home plate in that sort of a game, you shouldn’t be going.

Not everyone agrees with me, but for a century of baseball the unwritten rule was: Win the game, but don’t go out of your way to embarrass the other guys. And don’t you know it, but the next night the Marlins came back in the ninth inning to deliver a crushing loss to Boston.