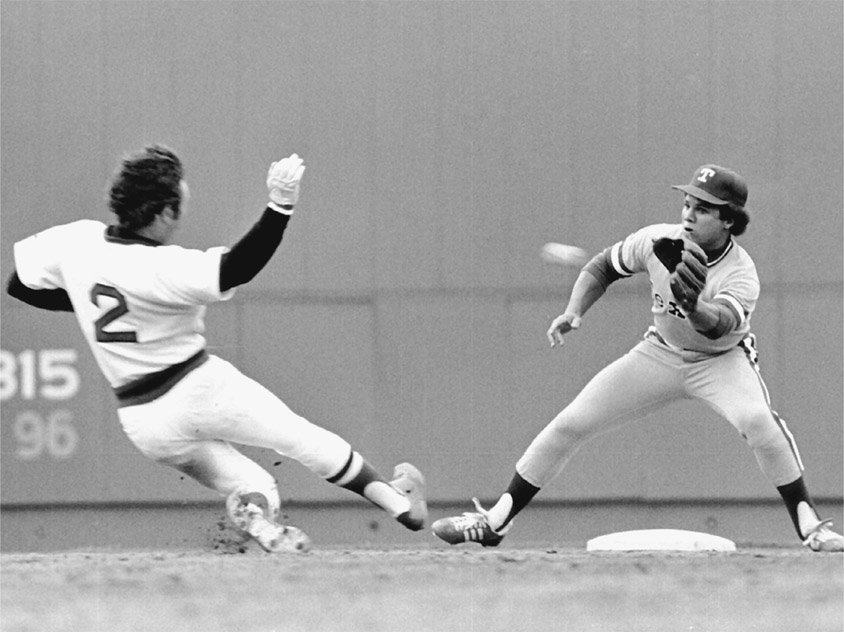

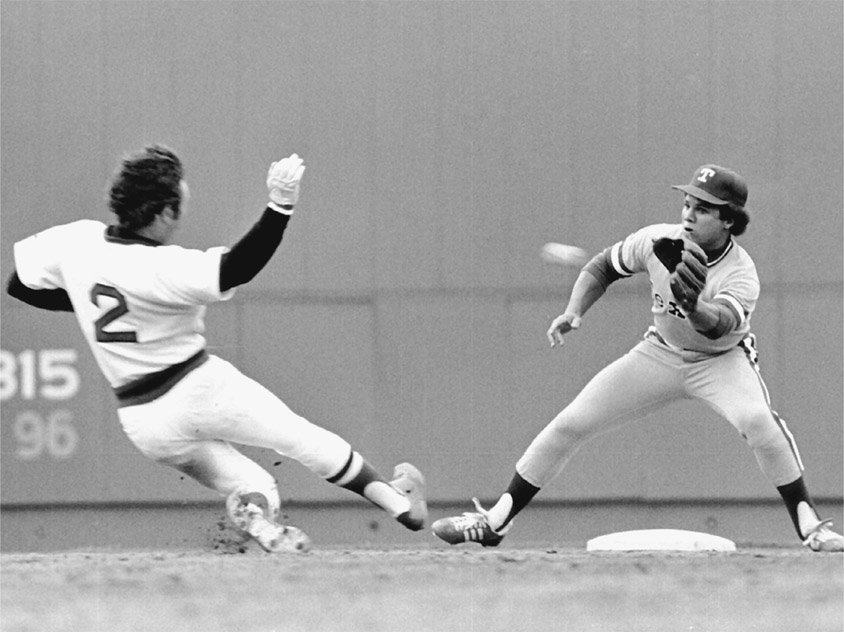

I’m sliding on an attempted steal; the play is going to be very close.

Photo courtesy Boston Red Sox

C H A P T E R T W E N T Y - T W O

Sooner or later, every ballplayer gets the yips. That’s when nothing seems to go right.

A hitter can go to the plate fifteen times in a row and feel on top of the world. Every pitch looks hittable; nothing is too difficult for him to get to. Or he’s in a series when he’s not seeing great pitching. Every time he swings the bat, he’s making good solid contact and getting hits.

All of a sudden, on that sixteenth time at bat, he’s out in the Twilight Zone. Now he puts together four or five bad at bats. He may have three line drives in those at bats, but they’re right at somebody.

Rem Dawg Remembers

Throwing It Away

Sometimes players get in the habit of making bad throws or develop a phobia about throwing, like what Chuck Knoblauch went through when he was with the Yankees. From the second baseman’s normal position to first base is the easiest throw to make in the whole game; it’s only about 40 feet. But sometimes that’s worse, because the more you think about it, the more the chance you have to make a bad play.

I’ve seen catchers who couldn’t throw the ball back to the pitcher; Mackey Sasser went through that with the Mets.

Who knows why that happens? A player might make one bad throw, it gets in his head, and after that he just anticipates something bad happening every time he throws the ball.

They tell players they’re supposed to feel good about it anytime they hit the ball well. Baloney. I wanted hits. I didn’t care what those hits looked like. I didn’t care if they were bloops or bunts. I just wanted hits.

Hitters can go 4 for 5 without hitting the ball out of the infield and feel like they’re on the greatest streak in the world. And they sleep well that night. Or they could hit five hard line drives right at somebody and be 0 for 5 and not sleep a wink.

When they try to get out of a slump, most players go back to the basics, working on their mechanics. And for many it finally gets to the point where they say, “Okay, what is my main trigger? What is the one thing that I think about to get me going when I’m swinging well?” It could be making sure his shoulder stays in, making sure his head is on the ball, making sure he’s lining up back through the middle, or making sure his hands are high. Whatever it is, players usually get down to one basic thing and work on it and eventually come out of it.

But mentally it kills you.

One thing about baseball is that even when things go well, players don’t get to enjoy it very long because they’re out there every day. A player may have a great night and win the game for the team. But when he wakes up in the morning, he’s focused on the next game.

And it is the same with slumps. The days roll one into another. Players get down on themselves and depressed and they get to thinking all kinds of things: “My season’s going down the tube. I had a man on second and I couldn’t drive him in, and we lost by a run.” It just builds and builds and builds.

Through the course of a long season, the best players adjust to those things better than others. A lot of it has to do with personality.

One season the Angels were playing horrible baseball, and so management brought a hypnotist into the clubhouse. In those days that was the cutting edge. He was giving us this stuff about positive thinking and getting negative thoughts out of our minds. Almost all of the guys were rolling their eyes and poking each other in the ribs.

“I like radio better than television because if you make a mistake on radio, they don’t know. You can make up anything on the radio.”

FORMER YANKEE SHORTSTOP AND BROADCASTER PHIL RIZZUTO

All of a sudden Frank Tanana is standing up and the hypnotist is telling him, “Walk here, walk there,” and he was doing it. Tanana was a great pitcher, but he used to like to have fun. To this day, I don’t know if Tanana was faking it or if he was for real.

Looking back, I guess we should feel bad for the poor guy who came in to help us. I imagine he was used to working with people who were serious and looking for help, and there he is with a bunch of people who are saying to themselves, “What are we doing here?”

I remember walking out of the place, and everybody was just shaking their heads.

We went out and got killed again that night.

There are many reasons why good fielders make errors: bad mechanics, bad hops, and bad reads on a ground ball or fly ball, among them. Players sometimes go through stretches where mechanically they feel they are doing everything right, but it seems as if every hop they get is a bad one. Sometimes the things that go wrong are so minor that players don’t even know the cause.

I know that some coaches say they want players who would like to have the ball hit to them on every play. Maybe there are those guys, but I think there are more guys who say, “I’ll take it if it comes to me, but I’d prefer it to go somewhere else right now.”

Ballplayers compete nearly every day. It’s not like football where they play a game on Sunday and then they have five days to correct whatever problem they had in that one game.

When a hitter goes into a slump, he may go 0 for 20, which sounds bad, but that’s really only four games. And the same sort of thing can happen defensively. There can be a stretch of a few games where the ball is just eating up a fielder; it seems as if he’s always out of position to make the plays, and that when he is in the right place, he gets a bad bounce and it hits the heel of his glove.

When a batter is hitting very well, players sometimes say he is “in the zone” or “in the groove.” It could end with the next at bat, but for the moment everything seems to be working the proper way. He is staying back on the ball, he is soft on his feet, his eyes aren’t jumping, his swing is perfect, and he is not getting any nasty pitches. It seems like every pitch is down the middle of the plate, and the ball looks the size of a basketball.

That is heaven, what hitters dream about. Players who bat .350, hit 40 home runs, and drive in 100 runs have to feel that way a lot more than I ever did.

Remy Says: Watch This

Hands-Down and Backs Up

One of the crazy things about baseball is that you can’t play if your hands are messed up. Football players will laugh at you; they play with broken arms. But so much of baseball involves the hands that any kind of injury to the wrist, hand, or fingers is a devastating injury for a baseball player. He can’t throw, catch, or swing a bat.

Players like Derek Jeter who tend to lean into the strike zone get plunked on the hands often; more and more guys, including Jeter, are wearing another piece of body armor on the backs of their hands.

Finally, there’s nothing worse than trying to do anything with a bad back; just think about swinging a bat and playing a base in pain.

“Remy is very dedicated and reminds me a lot of Pete Rose in that he’s hustling all the time. He loves to play. As a matter of fact, he’s the first one at the park. He gets there before anyone else.”

CALIFORNIA ANGELS COACH JIMMIE REESE, 1976

On May 12, 1979, I went 5 for 5 in a game at Fenway against the Oakland Athletics, four singles and a double. The starting pitcher was Rick Langford, and he was someone against whom I had a lot of luck. I remember one time I bunted on him for a base hit and he got really ticked off. And I guess he was still frustrated because he never managed to pitch very well to me.

There are certain guys whose pitches a hitter sees exceptionally well. There is nothing they throw that makes the hitter feel uncomfortable. The pitcher could be a future Hall of Famer or some guy they just called up from Triple A.

I had good luck against Luis Tiant when he was with the Red Sox and I was with the Angels. He had this big herky-jerky windup, he had chains that you could hear jangling, and he had his wallet and his keys in his pocket. And yet for some reason, his ball looked good to me. I also faced lousy pitchers, guys other batters were just pounding the stuffing out of, and I couldn’t hit them.

One Boston and American League record I share is hitting six singles in one game. The game, at Fenway against Seattle, began on September 3, 1981, and went nineteen innings before it was suspended at 1:00 a.m. Then we came back the next night to resume the game. I got my sixth hit in the bottom of the twentieth inning, with a man on first, and I was left standing on second base with the game-winning run when the last out was made. Six hours of baseball, I go 6 for 10, and we lost 8–7.

In 2003 my record got company: Nomar Garciaparra had six singles in six at bats plus a walk in a disastrous thirteen-inning loss at Philadelphia.

Once a player gets established in the major leagues, unless he gets injured, batting averages are usually pretty stable from year to year throughout the prime of his career.

If a player is a career .290 hitter, most years his batting average will be right in that range. The occasional off-season is usually due to injuries or personal problems. You almost never see a complete drop-off unless the guy is at the tail end of his career and he is just gone—he’s slowed up and he can’t physically do what he used to do.

One recent trend, and I think it’s a good one, is sending major leaguers down to the minors for rehabilitation from injury. A player hurt in the middle of the season and out of the lineup for a month doesn’t have the benefit of spring training when he returns. And his team may be fighting for a spot in the playoffs and not too happy about putting someone in the lineup who is not playing to the best of his ability.

If that player goes down to the minors, he can take at bats against live pitching and in game situations. It is not going to be the same quality of pitching he sees at the big league level, but it helps a lot. And when he plays in the minors, the games don’t mean anything—to him—and the stats are not going to end up on his baseball card. That takes a lot of pressure off.

As I’ve already noted, I originally hurt my knee sliding into home plate in 1979 at Yankee Stadium when I tried to score from third on a short pop-up.

I never should have gone, and I ended up catching my spikes as I tried to slide into home plate. I only played in seven more games for the rest of the season. And though I had averaged thirty-five stolen bases in my first four seasons, the most I would get in the rest of my career was sixteen.

“Does Cal know?”

RYAN MINOR, BALTIMORE ORIOLES THIRD BASEMAN IN 1998, AFTER BEING TOLD HE WOULD START IN PLACE OF CAL RIPKEN JR., THE FIRST TIME RIPKEN HAD MISSED A GAME IN 2,632 CONSECUTIVE OUTINGS

It was a major concern for me because I injured my left knee, the one that is always exposed to the runner coming in on a play at second base.

As my career went on—and with each operation I had on the knee—I was more concerned and probably not fundamentally as good as I should have been at making double plays. I became protective, getting that knee out of there. I would find myself throwing off one leg instead of nicely planting myself and making a good throw. For example, I might lean on my back leg, get my left leg out of the way, and make a sidearm throw. It’s not something you plan on doing, but you know that one more blow to the knee puts you back in the operating room, having it worked on again.

I’ve had ten operations on my knee and one on my back. I used to love to play tennis, but I can’t do that anymore. Even golf bothers me. I can still jog straight and slow; the side-to-side stuff I can’t do. I’m not going to get anywhere very quickly. Now my goal is to have an injury-free off-season.