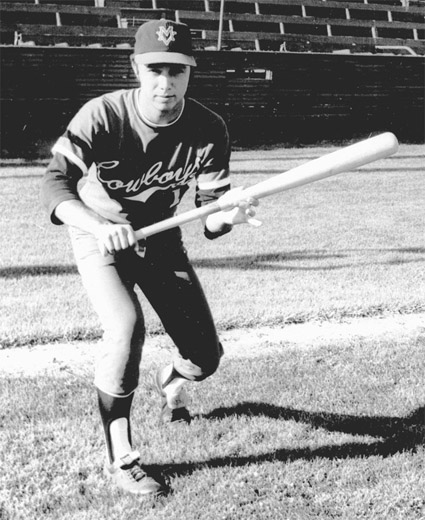

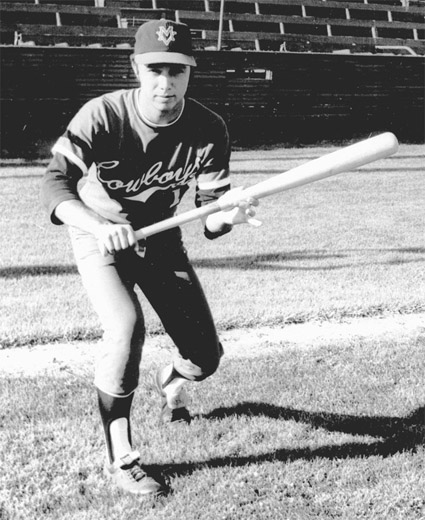

Way back when, as a member of the Twin Falls Cowboys in Idaho, part of the Rookie League.

Photo courtesy Boston Red Sox

C H A P T E R T W E N T Y - T H R E E

Pay attention the next time you see a rookie taking his first at bat in the major leagues. This is it: He is in the Show.

If he is anything like I was, his knees are shaking. He might be facing a pitcher he has watched on TV for the last four years, and all of a sudden there he is, 60 feet 6 inches away.

Getting a major league uniform and putting it on for the first time is a pretty awesome experience. The rookie is the story of the day for the sportswriters, and they’re all going to ask him the same question: How does it feel to be here?

From the point of view of major league organizations, the purpose of the minor leagues is player development. The teams down there try to win games, of course, but if the major league team needs help because of injuries or problems, it can promote the best players in Triple A to the big club overnight.

Players do not always make their way through the minors in a step-by-step fashion, from high school or college to a rookie league and then A, Double A, and Triple A leagues. A guy out of college, a high draft choice, may start in Double A baseball. A kid out of high school may begin in a rookie league.

At the rookie league level, the kids have to be taught everything. A lot of the players are from other countries, and in addition to baseball, they have to be taught how to live here and learn the language.

I think a player who can make it to Double A ball has a legitimate shot at getting to the major leagues, sometimes without spending time at Triple A. The scouts and coaches at minor league levels can pretty quickly recognize the proper level for a young player.

At the Triple A level, you see veteran players who have spent time in the big leagues and hope for another shot, and solid but unspectacular utility players stockpiled by major league teams as insurance in case one of their regulars goes down with an injury.

Players the organization thinks are two or three years away from being major contributors at the major league level are often at Double A.

Teams generally expect their high draft choices to speed through the minors. And in today’s game pitchers who have any ability at all are likely to rise even faster.

Years ago almost every player spent four or five years in the minor leagues to ensure that when he got to the big leagues, he was prepared to play. But today the huge sums of money clubs give to their best prospects pushes them through much more quickly. If the organization gave a prospect a ton of money, it wants to move him up to the major leagues fast.

Rem Dawg Remembers

A Career Begins

I love to see guys get a hit their first time up because I know how much pressure that takes off their shoulders. One of the coaches will usually ask an umpire for the ball, and it will be kept in the dugout. The kid will write on the ball that it was his first major league hit, and it will be something he will have his whole life.

I still have the baseball from my first hit in 1975. I wrote the date and the pitcher; I left off the fact that I got picked off base. I put that on my shoes.

“I think about baseball when I wake up in the morning. I think about it all day and I dream about it at night. The only time I don’t think about it is when I’m playing it.”

RED SOX GREAT CARL YASTRZEMSKI

The chances of making it to the major leagues are also improved if the player is coming to a weak team. A good club may try to filter in one or two new guys each year. Teams that aren’t very good rush their players more.

When it comes to pitching, nearly every major league team is always looking to improve. Every year we go to spring training and look at the press guides and see young pitchers who have been in the minor leagues for just one or two years. That’s practically nothing when it comes to baseball experience, and here they are getting a crack at the major league team.

Teams are always looking for players with the “five tools”: hit for average, hit for power, blazing speed, exceptional fielding, and strong throwing ability. If a player has all five at the Triple A level, he is probably going to be a pretty good big league player.

A player’s stats in the minor leagues give some idea of his likely numbers in the big leagues, but there is no certainty. There have been many players who come up from a great career in the minors and end up as total disasters in the big leagues. And there are players who make it to the majors and turn out to be much better hitters than their minor league record indicated.

In 2007 Dustin Pedroia was given the chance to be the Red Sox starting second baseman on the basis of his success in the minor leagues and his history as a star at Arizona State. Playing college ball in 2003, he batted .404 across sixty-eight games. Once he signed with Boston, he moved rapidly through the minor leagues, batting .308 for his minor league career.

As a starter for the Red Sox, he struggled for the first few months of the season, but you’ve got to give Red Sox management and coaches credit for sticking with him; he went on to post a very solid rookie year, batting .317 with 57 RBIs and 8 home runs.

Jacoby Ellsbury put up similar numbers as a minor leaguer and performed very well as a late season call-up and then in the postseason in 2007. He shows great promise as a speedy outfielder who can hit for average.

Teams depend a great deal on the expert advice given by their scouts and coaches. A good scout can look at a young man and project a year or two ahead to his likely capability.

Let’s say there’s a hitter at Double A who is leading the league in batting average and has hit twenty home runs. Good scouts and coaches know if this guy is a good hitter or not. He may be facing weak competition in the minor leagues, but he may have a beautiful swing. Or his batting skills will not match up well against a major league curveball.

That’s what makes a good organization: scouting, smart draft choices, and the development of the players they have under contract. When all of the scouts for all of the teams decide a player is not major league material, it’s probably not a mistake.

And when young players get to the big league level, there are many other factors that help—or hurt—them. The lighting is better for night games, which may help them as hitters. On the other hand, the pitchers are much better, and so is the defense. A ball that would have fallen for a triple in the minor leagues is going to be caught by a major leaguer.

Each time a player moves up a level in the minors, his lifestyle improves—a little. There’s a major improvement in the jump from Double A to Triple A because making that move is pretty much the end of six-hour bus trips from city to city.

Triple A is pretty good nowadays. Under the latest collective bargaining agreement, a player who signs a contract with a major league team received a minimum of $30,000 in his first year in the minors, with his salary doubling if he signs a second contract or if he plays at least one game in the major leagues.

Remy Says: Watch This

Watered Down

An unfortunate side effect of quickly promoting the better pitchers to the majors is that minor league hitters end up facing less-substantial pitching than they’ll see in the big leagues.

Some of the low minors, though, are not part of a major league organization and there the money may be very thin. But coming to the big leagues is a whole different story. You play in the best stadiums, on perfect fields, and under great lighting. Someone picks up your luggage and delivers it to your room when you’re on the road. The team bus drives right onto the tarmac at the airport to get you to the chartered plane. And you get enough meal money to eat very well.

The minimum salary for a major league player in 2008 is $390,000, plus first-class airline travel and hotels and an $85 per day meal and tip allowance. That’s why they call it the big leagues.

Sometimes you have to wonder which is worse, having the lowest batting average in the majors or being the batting champion of Triple A. Actually neither is bad because you will get attention from one major league club or another. What’s worse is being a lousy hitter in the minors.

Then there are players who set batting records in the top minors and stay there; they’re sometimes called Four A players because they find themselves somewhere between Triple A and the major leagues. They get stuck in the upper minors because they may have home-run power but can’t do anything else. They might not be able to run or are weak fielders. They don’t quite have the skills to get up to the majors or to stay there.

That’s got to be frustrating. They know they are not going to be great players in the big leagues. They’re making a decent living at the minor league level, but they really have to love to play to be down there for years.

Remy’s Top Dawgs

Wade Boggs was a guy who had been in the minor leagues for a long time, and when he came up to the Red Sox, we thought other teams would find a way to get him out. They never did, and he had a fantastic career as a batter.

What impressed me most about Boggs was that he became a good defensive third baseman; he was not one when he came to the majors. He spent as much time and effort on making himself a better third baseman as he did on hitting. I give him a lot of credit for that because most guys just want to hit. He took it personally when people didn’t think he was a good third baseman, and he got to the point where he won a Gold Glove.

There’s an awful lot going on at spring training besides major leaguers getting into shape for the coming season. Teams bring to camp their best prospects from Triple A, Double A, and sometimes lower.

The major league manager and front office may be seeing a young player for the first time. This kid may not be ready for the big leagues, but early in the spring, he may get more playing time than the regular players. Veterans may take two at bats and then head to the clubhouse or the batting cages; the minor leaguers play the rest of the game. It’s hard to judge their skills because they’re probably batting against the other team’s minor league pitching. Even so, some kid may catch the eye of the manager. He may not be a top prospect in the organization, but the brass may like what it sees.

Still most minor league players know they have no chance for an immediate promotion. They are there for the first couple of weeks, and then they are going to start filtering down to the level where they belong. Every spring there are maybe three or four or five players who are on the bubble—guys who could be called up to the majors or sent down to the minors, depending on the team’s needs and a judgment by the managers.

I began my minor league career with the Twin Falls (Magic Valley) Cowboys, hitting .308 for the 1971 season. Next stop was Stockton in the California League, batting .265. Then Quad Cities in the Midwest League, batting .335 in 1973.

I made the jump from the minors directly to the opening-day lineup of the Anaheim Angels in 1975. I had a good year at Double A El Paso of the Texas League in 1974, hitting .338 with 34 doubles, and they called me up to Triple A at Salt Lake City in the Pacific Coast League toward the end of the season, where I batted .292 in forty-eight games.

At Salt Lake City I met a guy named Grover Resinger. He told me, “If you come to spring training and play like you have this year, you’ve got a good chance of making the team.” I thought, “Yeah, right.”

In the off-season I went down to Mexico to play winter ball. I hated playing down there, but it gave me some good experience.

I was shocked when I got to spring training with the big club in 1975 and saw Resinger in uniform as a coach for Dick Williams, the manager. He had sent word to the brass, and Williams focused on me the whole spring. He liked what he saw, and they were looking to remake the team with some younger players, and that’s how I got my crack.

As I look back, I realize I could have gone to spring training and messed up and not have made the team and maybe never gotten another chance. But I got off to a good start, hitting .313. It wasn’t until late in the spring that I was told that I was going to make the team and that I was going to be the starting second baseman on opening day. I couldn’t believe it.

Remy’s Top Dawgs

Carl Yastrzemski was one of the players I looked up to as I was coming to the majors, and then I had a chance to play with him at the end of his career. The thing that will always stick out in my mind about Yaz was how passionate he was about hitting. To the day he retired at age forty-four, he could still hit a fastball. He constantly made adjustments to be able to handle that pitch late in his career.

I remember I was interviewed by a reporter for the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner. I told him: “It’s the thrill of my life. In the minor leagues you are so far down you can’t even see the big leagues. You wonder if you can make it to Triple A ball. Then you are in the lineup opening day.”

The Angels had Denny Doyle at second base, and because I was doing well, that gave them the chance to trade him to Boston, where they really needed a veteran, and he helped the Red Sox win a pennant that year. Ironically, when I was traded to Boston, I ended up replacing Doyle again. He couldn’t have been a nicer guy, though.

In my third year in the major leagues, at age twenty-four, I was named captain of the Angels by manager Norm Sherry. According to the sportswriters, I was the youngest captain in recent years and maybe the greenest ever. I was honored but not all that comfortable; there were a lot of older and more experienced players in the clubhouse. The opening day roster on that club included Don Baylor, Bobby Bonds, Joe Rudi, and Frank Tanana. Nolan Ryan was in his eleventh year in the majors and already on his way to the Hall of Fame.

But if the manager asks you to be captain, what are you going to do, say no? I looked at the newspaper clippings. “I’ve been thinking about it for a while,” Sherry told the Herald-Examiner. “Jerry isn’t the star type. He’s a tough kid. He plays hard every inning. He’s a peppery little guy.”

I boldly made a prediction: “It’s a real honor,” I told the press, “to be captain of a team that probably will be the best in our division in October.” As it turned out, we had a lot of injuries that year, and I ended up as the captain of a sinking ship. We finished 74–88, far back in the pack.

I appreciated what Sherry was trying to do, though. I felt like I played hard all the time, ran out every ball, worked hard at batting practice, and was a dirt-dog player. I think I was named by Norm as an example of the way you are supposed to play the game—not because I had the best ability.

The previous captain had been Frank Robinson, who had the job for just a month in 1974 before he was traded. Anyhow, there’s probably no need for a captain on a major league team. I think there are guys who lead by example. You could name the best player on your team as captain, but he may not be the guy other players will talk to or who will quietly go to other players and give them a prod.

Maybe it would have been better if it happened later in my career. Fortunately, Anaheim was not a huge media market like Boston, where the captain might have thirty reporters hanging around his locker after a game asking him to speak.

There are no official duties in baseball for the captain. I got to bring the lineup out to home plate every once in a while and do some ceremonial things. Today many teams do not have a captain. The player rep deals with grievances and union matters, and he is chosen by the players and not the manager.

My next-to-last game, on May 15, 1984, was Roger Clemens’s major league debut. The Red Sox were in Cleveland and Clemens got knocked around, giving up eleven hits in five innings before a crowd of 4,004 people in huge old Cleveland Stadium, where they could fit something like 78,000 fans. I drew a walk, and Glenn Hoffman came in to pinch run for me. My knee was real bad and I couldn’t run; Hoffman had some kind of injury, too.

My last game was a few days later at Minnesota, where I came in as a pinch hitter in the seventh inning and flied out to left. We lost the game. I didn’t know it was my last game at the time, but I knew I was getting close.

Unfortunately most guys don’t know when it is their last at bat. They either leave because of injury or when nobody wants them any more. When Cal Ripken played his last game, it was against the Red Sox, and he ended up left on-deck when the final out was made. The Red Sox got a lot of abuse about that, but the manager wanted to win the game.