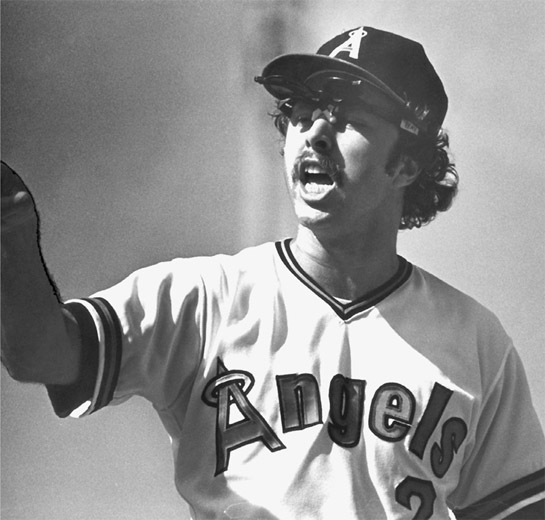

Me arguing? I think I must have been directing an infielder or an outfielder. Yeah, that’s my story.

Photo courtesy Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim Baseball Club

C H A P T E R T W E N T Y - F I V E

Years ago, managers had much more power. The old-school type of manager used to say, “It’s my way or the highway.”

Baseball is very different from football. For example, in pro football many contracts aren’t guaranteed; if a football player doesn’t perform, he’s gone. But in baseball, when a player is being paid $20 million a year, the front office expects him to be in the lineup every day. A manager has to have the support of the front office before he can take a high-paid superstar out of the lineup.

Today managers have to learn how to cater to each different personality in the clubhouse: superstars, solid regulars, and bench players. The manager has to develop a relationship with each one of them to get the most out of their personalities and talent.

But the manager still has to maintain some rules that everybody has to live by. Then he hopes the veteran and star players are willing to abide by them, because if they are not, it can be chaos.

When it comes down to it, the easiest part of the job is managing the game itself. The most difficult thing is dealing with the players and dealing with the media. Managers are constantly second-guessed on moves that they make, especially in major media markets like Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Los Angeles.

What loses managers the most games are poor pitching choices late in the game: staying with a pitcher too long or bringing in a guy who has pitched too much recently. Those decisions are more important than things like whether to position players on the lines in a particular situation or bunt or hit away on offense.

Managers are now paid better than they used to be, with several earning a million dollars or more per year, which is a nice piece of change in any situation, but it’s still an unusual situation because many of his employees are pulling down three, five, or fifteen times as much. The pay scale in baseball has been way out of whack for a long time. Among the highest-paid managers in baseball: Bobby Cox of the Atlanta Braves, Joe Torre of the Los Angeles Dodgers, Tony La Russa of the Saint Louis Cardinals, and Boston’s own Terry Francona.

It’s hard to deal with a superstar, but it can be done. The manager has to develop some kind of relationship and hope he can communicate in a way that makes the player respect the boss.

I’m not saying that players walk in and say, “I am making $10 million, and you are only paid half a million, and so I am going to walk all over you.” But there is a certain sense of independence for a guy making $10 million a year.

In some ways the situation is similar to that in the world of entertainment, where a big star earns more than management. Baseball is entertainment. When folks buy tickets to a game, they are there to watch Josh Beckett or Daisuke Matsuzaka pitch or Kevin Youkilis play first or David Ortiz or Manny Ramírez come up to bat; they are not paying to see the manager make a pitching change.

But it is the manager who takes the heat when things go wrong. The manager is measured in wins and losses; it’s pretty much as simple as that.

A good manager has to keep a bit of distance. When I was playing, I had managers come into the bar and have a cocktail with me; that was fine. But if the manager gets too chummy with one guy, other players become resentful.

There are all kinds of personalities in a manager’s uniform: screamers, player’s managers, and disciplinarians.

“I never thought home runs were all that exciting. I still think the triple is the most exciting thing in baseball. To me a triple is like a guy taking the ball on his 1 yard line and running 99 yards for a touchdown.”

HALL OF FAMER AND HOME-RUN KING HANK AARON

I learned long ago that if you scream at your children all the time, they stop listening. The same goes for screamers as managers.

A player’s manager really tries to get along with the team. They may have different sets of rules for different members of the team. They try to earn the respect of their players by standing up for them.

When a team with a player’s manager doesn’t perform well, the front office will often make a change to somebody who is supposed to bring some discipline. It’s a never-ending cycle. Owners just hope they catch one personality type that works for a while.

Dick Williams, one of my managers when I was with the Angels, was one of the hardest men in the world to play for. He was a very good baseball guy, but he was very demanding and not afraid to get in your face. But I remember talking to him later in his career when he was with Seattle. He said, “I can’t do this anymore, it is not the same. I can’t handle myself the way I want and have the same success as I did in the past. It is a different game.”

And I know what he meant by that. The change is mostly about money. Managers are not only dealing with the player, they are dealing with the player’s agent. And if it is not the manager, then it is the general manager who hears from the agents, and then he gets on the phone.

In his tenure with the Red Sox, Grady Little certainly qualified as a player’s manager. He was a quiet, one-on-one type of manager, a laid-back Southern guy. But that didn’t mean he didn’t burn inside when things went wrong.

There’s no arguing with results: two World Series rings in four seasons for Red Sox manager Terry Francona.

There is no question he is a player’s manager. He treats them with respect and he has gotten their respect. There are no surprises for the players; they know what to expect. And he is very smart in surrounding himself with very good people like his bench coach Brad Mills and pitching coach John Farrell.

He is a much different guy than when he first got here. In the beginning he was always on edge with the media; success brings confidence.

In 2007 he did a good job adjusting to the type of players he had. He had some guys with speed, so he had them run more. He had a few guys who could hit-and-run, so he called for more of those plays. He called more sacrifices.

Everybody wants to be liked, whether they are a hard-ass or a cream puff. That’s very difficult in baseball. There are twenty-five players on the team during the season, and maybe another ten or fifteen move onto the squad for parts of the season because of injuries or trades. The manager can’t keep all of them happy. There are only nine or ten starting in a game, and all of the others are not.

Can you imagine going to work each day knowing that some players are really ticked because they haven’t been playing and knowing they’re going to come in and argue?

And throughout baseball there are certain players who are cancers on a team. There’s no point naming names—if you follow baseball, you know the guys I mean. They are never-ending problems in the clubhouse and on the field.

Remember that many players on a major league team are just kids, young adults in their early twenties. They have been playing ball their whole life. A lot of them don’t have the skills to be out in the business world and know how to conduct themselves. And then some clown comes into the clubhouse and they are easily misled. It can destroy their career for a couple of years, until that cancer is gone.

A team is together from February 15 until October 1, and with luck a bit longer. That’s a long time, and it’s every single day with very few days off. They travel on airplanes for long coast-to-coast flights. They are in that same crowded clubhouse day-in and day-out.

There are all sorts of personalities from different parts of the world. There are guys who come from wealthy families and kids who didn’t have shoes growing up. Somehow they all have to click together, and the bonding force is the game they play. The one thing they all know is baseball.

There have been clubs that have been successful even though they have had an unhappy clubhouse. The Oakland Athletics back in the 1970s and the Yankees in the 1980s had a lot of trouble between players. And there was a lot more going on that fans never heard about.

Can a team be successful with that kind of environment? Sure. But is it pleasant to be around? No.

Players have a tendency to shut up if the team is winning because they’d look like idiots if they said something was wrong. But once the team starts sliding, that’s when it all comes out, and then it just steamrolls out of control.

Remy Says: Watch This

The Firing Line

In the end a manager is judged by wins and losses. If a player signs a five-year deal, he is not likely to be fired if the team does poorly. But the manager takes wins and losses very seriously, sometimes more seriously than the players.

When things go badly, the firing order usually starts with the manager. The general manager gets a break for a while, but eventually, if the losing keeps up, it’s his turn to go.

I thought the treatment of Joe Torre by the Yankees at the end of 2007 was disgusting. Had I been Joe Torre, I would have just left. But I think he wanted them to fire him. Torre was the perfect guy for that job. But perhaps Joe needed a change himself. How much can you take? The Yankees won all those championships and still they expected to win a championship every year. Well that’s not going to happen.

How much abuse can you take before saying, “I don’t need this.”

I always thought that George Steinbrenner was a little bit jealous of Torre because Joe got a lot of credit when they won.

Joe knew the position he was in. He could call his own shots. And he did.

As I have said this is not football, where the coach gets the whole team fired up before it goes out on the field. But it is important to have a manager who can motivate in all sorts of ways. There are some players who need their rear end kissed, and others who need a kick in the same place.

We always had these speeches at the beginning of spring training, and many of them were silly. The manager would stand up and say something like, “I feel we’ve got a real good club this year. We’ve got a chance to do something.” As a player, you look around the room and you know if you have a good enough team to go to the World Series. But you get that same speech.

Over the years I’ve thought about what I would say if I was a manager. I would tell the team:

I want to get to the World Series, and I want to win it. What I want you to do is go out and have the best possible year that you individually can have. If you do that, we are going to have a good team.

I am the one who’s got to worry about the wins and losses. Motivate yourself, be prepared to play every day, and you will reap the rewards through a world championship or a better contract.

Let’s face it, baseball is an individual game. A manager can talk all he wants about the World Series, but a player’s personal goal is to have his best year ever. And if a few players on the team do just that, together they’ve got a good chance to win.

There is no such thing as a time-out in baseball. During the game a manager is not going to call a team meeting. There aren’t even all that many team meetings in the clubhouse. There may be a “go kick ass” meeting once or twice a year. “You know we are better than this,” the manager or one of the coaches will say. “We are as good as the team that’s in first place. Let’s get our act together.”

If a team loses five in a row, a manager might not be able to help him-self. He may not be seeing the effort that he wants to see. Players are not running hard. Runners are not trying to take out the second baseman on a double play. He’ll have a meeting for a pep talk, or a screaming match, or something in between.

But team meetings are rarely effective. You get more out of individual conversations with players.

It would be easy to sit here and say that catchers, second basemen, or shortstops are particularly well suited to be managers because they are always involved in the game. But I don’t think that’s true. Much more important is personality. As a manager, can he get along with people? Is he a leader? Can he discipline people the right way?

He’s got to be able to communicate with the players and care about them as people. They have feelings. They have families and personal problems.

Can this person deal with newspaper, radio, and television? If he can’t handle the media in serious baseball towns like Boston or New York, he’ll get crushed no matter how good a manager he is.

A manager who has played in the major leagues commands some immediate respect because players know he has been to war. He understands the ins and outs of being a player and living the big league life. It’s very difficult for a guy who never played at a major league level. Players believe that he doesn’t understand them because he has never gone 0 for 20 at the plate.

On a day-to-day basis, the manager’s job is centered around making up the lineup. Working with his coaches, he goes over scouting reports and individual matchups of his players against certain pitchers. The manager usually scribbles the lineup on a piece of paper three or four hours before the game and hands it to the bench coach, who will transfer it to the official lineup card given to the umpires; a copy is posted on the wall of the clubhouse.

Many times, though, the manager has to wait and see if players are physically capable that day. A regular may have to go through physical therapy before he knows whether he can play or not. And sometimes a player gets hurt in batting practice or comes to the clubhouse with the flu.

Remy Says: Watch This

The Right Man for the Job

I think another key to success as a manager is not asking a player to do something he can’t do. You don’t ask Manny Ramírez to try to sacrifice to move a couple of base runners along. He hasn’t done it, and he is not going to do it. (For the record, in Manny’s first fifteen years, he came to the plate more than 8,200 times, and he had exactly two sacrifice hits; they both came early in his career. I’m sure there’s a story behind each of them.)

You win consistently by not putting players in positions where they are going to fail.

During the game, the most difficult decision is handling the pitching staff. The challenge is to use the right pitcher at the right time, and in the right matchups, especially late in the game.

Other decisions come down to the manager’s style. Some guys like to put on the hit-and-run play; others don’t. Some managers like to have their players steal. Some build their game around waiting for the three-run homer, while others try to manufacture runs one at a time with bunts, steals, and sacrifices.

Today, when a ballplayer who has been in the majors for a few years retires, he is pretty much set for life. How do you convince this guy to go back to Class A ball and ride buses and make forty grand a year managing rookies? At the minor league level, managers are not doing it for the money because there is little there. It comes down to motivation. How badly do you want to remain in the game? How much do you want to manage?

There are guys who walk away from the game when they retire, and you will never see them again. And then there are former players you’ll see at the park every day. They can’t get away from it.

In recent years we’ve had a few broadcasters come down from the booth and go into the dugout as manager. Bob Brenly had a couple of good teams at Arizona. If you’ve got Randy Johnson and Curt Schilling, that’s not a bad place to start your career as a manager. Buck Martinez didn’t have the same success in Toronto, but he didn’t have the same talent to work with.

Some people in baseball felt it wasn’t right for Brenly and Martinez to jump in at the major league level like they did, because they hadn’t put in years working as a coach or manager in the minors. Brenly had just one season as a coach for the Giants. But observing the game for a number of years from the broadcast booth, you see a lot more than you would if you were just focusing as a hitting coach on your hitters. And Brenly and Martinez had played in the majors, both primarily as catchers.

And in 2008, Joe Girardi took over as manager of the Yankees. Girardi went from catcher to broadcaster to bench coach to manager (Marlins) to broadcaster and back to manager. He replaced Joe Torre who went from player to manager (Mets and Braves) to broadcaster and back to manager (St. Louis, Yankees, and Dodgers).

When I finished playing, I worked for a season as a bench coach with the New Britain Red Sox in Connecticut. I went down there when the team was at home. At that time I felt that my future would be to start as a coach and eventually manage somewhere in the minor leagues and then the majors, but it hasn’t worked out that way.

I am still doing what I love to do, being around baseball, but I certainly don’t have anywhere near the pressure of a manager.

Is managing a goal of mine? Not at this stage of my life. You should never say never to anything, but I can’t imagine it ever happening.

As a manager I couldn’t go out there and play when the team needs help. I would just have to sit and watch, and I don’t think I would do it very well. And knowing my personality, I am not sure I would be cut out for it right now.

Although I’m pretty much an old-fashioned guy when it comes to baseball, I think I could adjust to today’s game and players and treat them individually. But I think the focus on wins and losses would just eat me up, because I know how I felt as a player when I was not playing well, and it wasn’t pleasant.

The 2003 season was very exciting and almost brought the Red Sox into the World Series; there was that little problem in the seventh game of the American League Championship Series when those New York Yankees came back to tie the game against Pedro Martínez in the eighth and win it in extra innings on Aaron Boone’s home run. It was also the last Boston game managed by Grady Little.

For most of the season, the Red Sox had been forced to make do without a strong closer. It took a long time for that bull pen to settle down. As a matter of fact, it took until the playoffs. I remember sitting with Little in his office and hearing him say, “Flip a coin. Who do we go to tonight?”

Little had been criticized during the season for not staying with the starters longer. Then finally, in the ALCS, he got into trouble for keeping Martínez in the game when the bull pen was pitching lights out.

Let’s imagine the conversation when Little went out to the mound in that inning. Grady asks, “How’re you feeling?” And Pedro says, “Fine.” That’s it.

If you ask a pitcher how he feels and he says, “I’m cooked,” he’s out. But when a pitcher with Pedro’s stature says, “I’m okay,” he stays.

What would have happened if Grady had pulled him out and the bull pen had coughed up the game? He would have been criticized for not staying with Pedro.

What would have happened if Pedro had told him he was cooked? Now Martínez is a quitter, right?

There are not many good scenarios here. Pedro was only up to about one hundred pitches when he began the inning, and as I watched that game, my gut feeling was that you could get another inning out of him.

I would have let Pedro come out for the eighth inning and let him try to get through another three outs, but I definitely would have taken him out after he gave up a hit. He was cooked.

Grady Little was not fired for that one incident. If things had worked out and they had won the game and gone to the World Series, he probably would have stayed; but because things didn’t work out, Little’s decision made it easy for the Red Sox to let him go.

Umpires are trained to get themselves into the best position to make calls on every conceivable play. You probably couldn’t find ten people in the stands—unless they’re the umpire’s family—who watch them that closely, but it’s an interesting routine.

The umps have a rotation they go through for every game situation. Everything has got to be covered; if there is a fly ball to the outfield that is not clearly out of the park, or if there is the possibility of fan interference, the umpire has to get out there and see it up close. Umps have to make sure the outfielder catches a ball and doesn’t trap it between his glove and the grass. And if one umpire goes out into the outfield to make the call, another ump has to cover for him in the infield.

As far as the quality of umpiring, I think all players will tell you the same thing: They want an honest and consistent effort from the umpires. If they get that, they can live with the occasional bad call. Players, managers, and attentive fans can see the difference between an umpire who is hustling and some hack who is just phoning it in.

You can tell if the home-plate umpire is having a good or bad day by the amount of conversation he has with the catcher and the hitter, and sometimes the pitcher. If you see a lot of long stares by the pitcher, you know he is not happy with the ump. If you see many batters stepping out of the box and questioning the umpire, you know they are not happy with his calls. Or, if you see catchers getting out of their crouch and having conversations with the umpire after a call, you can figure they’re not talking about the weather.