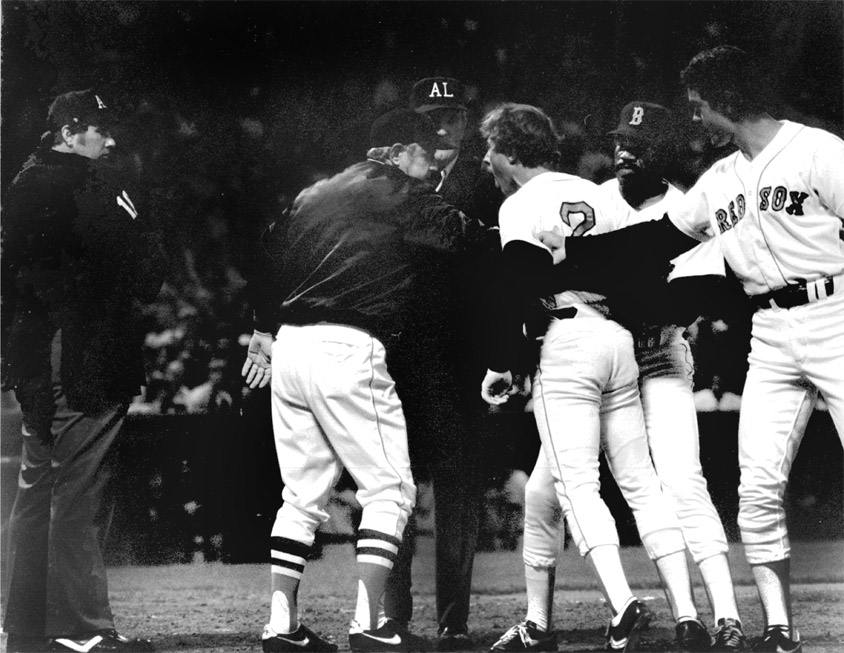

Me arguing? Manager Ralph Houk steps between me and the umpire at home plate. First-base coach Tommy Harper has a foot in there, too, and Dwight Evans reaches in from behind.

Photo courtesy Boston Red Sox

C H A P T E R T W E N T Y - S I X

The manager is in charge of day-to-day operations on the field, but in modern baseball he is by no means alone. Today’s Boston Red Sox, as an example, surround the manager with a bench coach, pitching coach, hitting coach, bull pen coach, plus first-base and third-base coaches on the field. Other support staff include a head trainer, assistant trainer, rehabilitation coordinator, and bull pen catcher. In the clubhouse are an equipment manager and staff.

Many managers like to have a bench coach beside them in the dugout as another set of eyes and ears, someone they can consult with to kick around some ideas. As slow as the game seems to some people, it speeds up when it comes time to make decisions.

Most bench coaches have had managerial experience at either the minor league or the major league level. Don Zimmer was with Joe Torre on the Yankees for many years and is a great baseball mind; there were times when Zim was responsible for running the offense.

On some teams bench coaches deflect a lot of the petty things that a manager doesn’t really need to deal with; players can go to the bench coach with their complaints, and then he can pick the right time to go to the manager and tell him what the player is a little ticked off about. In some ways it’s a bit of a good cop–bad cop deal. Even though the bench coach probably feels exactly the same way as the manager, he can tell the player, “Maybe you are right, let me talk to him about this.”

One of the most important moments in the 2007 World Series came late in the second game when bench coach Brad Mills flashed a sign to Jason Varitek; Tek passed along a message to Jonathan Papelbon who promptly picked Matt Halliday off base. Mills had learned something in his preparation for the game, and they executed it perfectly.

Mills knew from scouting reports that when Halliday tried to steal a base he often would do it on the first pitch; he was half way to second base with his lead and Papelbon eliminated the threat.

Mills is a hard worker and he gets along with the players. He is a manager waiting to happen.

The pitching coach is the most important specialist on the team. As I’ve said before, the game starts with a guy throwing a ball. A good pitching coach not only knows the mechanics of pitching and how to teach, but he also can communicate with his players. When a starting pitcher gets pounded, the pitching coach has to build up his confidence and get him squared away mentally and mechanically before he goes to the mound again.

Pitching coaches are probably more focused on one task than any other coach. They generally don’t deal with anything but their pitchers; they pay little or no attention to what hitters or fielders are doing.

Sometimes you’ll see a pitcher who’s struggling look into the dugout in the middle of the game to catch the eye of the pitching coach. The coach may give the pitcher a signal that says “keep your shoulder in” or “tuck your hands” or whatever they may be working on.

The pitching coach watches the starter on the mound, looking for problems; he will also let the manager know when he thinks it’s time to get out the hook. He is the one who has to bring the news when one of the relievers in the bull pen isn’t throwing well. He has to monitor how many pitches a reliever made in his last game and how many days in a row he has appeared. He will make the recommendation to the manager about who is available for that day’s game and who needs a day off.

Remy Says: Watch This

On the Mound

When the manager or the pitching coach comes out to the mound to make a change, he sticks around until the reliever arrives from the bull pen. What he usually wants to do is remind the new pitcher of the game situation: “You’ve got guys on first and second, and the batter may be bunting.” Or the pitcher may get the word that the manager expects a runner to try to steal a base.

Most managers listen very closely to their pitching coach. They would be foolish not to; the pitching coach knows the pitchers better than anyone. John Farrell is another hard worker, well prepared. You can see the respect the pitchers have for him.

One of the protocols of modern baseball is that the first visit to the mound is usually by the pitching coach, and the second is by the manager, coming out to change pitchers. The old baseball saying is: “I am the manager, I make the decisions, and you are out of the game.”

There are, though, managers who don’t even go out there to say good-bye. It might look like a lack of courage by the manager, but I disagree. The relationship the pitching coach has developed with the pitcher is much stronger than the one the manager has.

The first visit to the mound could have all sorts of purposes. It could be a motivational thing: “You’re throwing well. I don’t see any problems. They got a couple of cheap hits, so don’t worry about it.” Or there might be a young pitcher on the mound who has started the game by walking the first guy on four pitches and has thrown balls one and two to the next batter. Here comes the pitching coach just to change the pattern. “Calm down. Focus on throwing strikes, and let your fielders help you out.”

The coach might have noticed something in the pitcher’s delivery. Or he might visit to talk about a game situation, such as planning for a possible bunt or suicide squeeze.

Rem Dawg Remembers

A Coach Cares

A good coach is a guy who works with you, knows your personality, and knows when to approach you and when to stay away. The best coach I ever played for was Walt Hriniak, when I played for the Red Sox. If you didn’t hit, he couldn’t sleep. He cared very much.

There are also times when the coach goes out to the mound to delay, giving the reliever in the bull pen a chance to get loose. Many times the manager will signal the catcher or one of the infielders to go to the mound to kill some time. He will get back to his position, and then here comes the pitching coach to kill more time.

In any case pitchers are not fools. They can look behind them and see a reliever warming up in the bull pen.

A hitting coach usually has a particular philosophy. But the problem is that players have a tendency to listen to anybody they think can help them. A player might have a good relationship with the first-base coach and seek his advice instead of that of the hitting coach. He will listen to his brother. His father will call him, and his wife is going to offer an opinion. The guy in the fifth row is going to tell him something, and the parking attendant has a great suggestion.

Even when the hitting coach and the player have a good rapport, it’s a tough job. The coach has to deal with mechanics. He’s got to know the hitter’s strengths and weaknesses, what he does when he is swinging well, and what’s wrong when his swing has gone bad. The coach has to know the opposing pitchers, and he’s got to review videos with each batter.

And he has to deal with the individual psyches of the hitters, which is probably the most difficult thing to do. There may be one guy the coach can go to after every at bat and another player who had better be left alone until tomorrow.

Much of the work takes place in batting practice. Or a player may want to work one on one with the coach in the afternoon before a night game. The coach has to be there to do that for the player, and he’s got to be available to listen to him cry about why he is not hitting.

You would think hitting coaches could be judged on some very specific bottom lines: the team batting average, on-base percentage, and a few other measures. I have seen hitting coaches fired when all the offensive numbers look good: top five in batting average, second in runs, fourth in on-base percentage. What’s wrong with those numbers?

And even if the results are not that good, it is not easy to directly blame the hitting coach. He may be very good at his job, but it is out of his hands once he does the preparation work. He’s not going up to the plate—the players are. He may not have much to work with.

But if the relationship between the key players and the hitting coach is not good, he is gone. To be blunt about it: If four or five of the best players complain to the manager about the hitting coach, he will probably lose his job.

Hitting coaches always are sent packing when the team doesn’t hit, and they don’t get enough credit when it does.

Remy Says: Watch This

Individual Stats in a Team Sport

When a hitter goes in to negotiate his contract or enter into arbitration, he doesn’t take the team’s wins and losses in there; he takes his batting average and how many runs he drove in. He is not being rewarded based on the team finishing first or finishing fifth. He is rewarded on what he did individually.

Bull pen coach is another unusual specialty. He’s a guy who is dealing with players who are not involved in the play by play or flow of the game. Most of the men in the bull pen have roles that bring them in late in the game or in particular situations. One of the coach’s most important jobs is keeping those guys mentally prepared.

The bull pen coach will bring lineups and the scouting reports with him to the bull pen. Doing so allows him to go over with the setup man the batters he is likely to face when he goes into the game or prepare the closer for the batters due up in the ninth.

“The first guy you are going to see is Jim Thome. What’s our plan against Thome? How have you gotten him out in the past?”

He helps warm up pitchers and keeps in constant touch with them. If the call comes to get Corey to loosen up and he throws three pitches and reports that his shoulder doesn’t feel right, the coach has to let the manager know right away so they can make other plans. The coach has to be able to know when a pitcher is on and when he is not. He shouldn’t be fooled if a pitcher has an injury and wants to pitch anyway.

Remy Says: Watch This

Weight Training

The idea of weight training started about twenty years ago, pretty much toward the end of my career. Today, every team has a conditioning coach and they travel on the road with the team. Everything they do is focused on baseball. Players are not going in lifting weights just to lift weights. There is a purpose for everything.

There are lots of things I wish I had when I played. There’s the whole area of video libraries. Batters can go into the clubhouse between at bats and look at what they’ve got on the pitcher they are going to face. They can see every at bat they have had against him and how he tried to get them out.

The manager will meet with the trainer daily for the update on injuries major and minor. The trainer may see twenty guys a day for one thing or another, whether it is to put on a Band-Aid, tape an ankle, rub down a shoulder, or whatever. He handles immediate injuries. Beyond that, though, the trainer has an unusual relationship with the players. Players spend a lot of time in the trainer’s room with whatever injuries they may have. They also go in there for their normal daily routines, which might include things like stretching, applying hot packs, or taking whirlpools. And there is a lot of gabbing that goes on there; a trainer pretty much knows everything that is going on with the club.

Players have to trust that the trainer is not going to go running down to the manager if they are complaining in the trainer’s room.

In years past players used spring training to get in shape. There was no such thing as a strength and conditioning coach. All they had was a trainer in the clubhouse, and much of his regimen involved basic things like stretching and postgame whirlpools or ice packs.

Now teams are hiring college-educated physical specialists. They set up nutritional programs for the players. They design workouts and stretching plans. They are also responsible for rehabbing players with injuries and watching their progress very closely. And they set up off-season programs for many players.

From the front office’s point of view, the strength and conditioning coaches are responsible for keeping the players healthy and on the field. The quickest way to be out of a job is to have a lot of guys get hurt. And that was just what happened to the specialist hired by the New York Yankees for the 2007 season; as the team stumbled (and players broke down) in the first few months of the season, there were calls for the firing of the manager and the general manager . . . but the fall guy became the strength and conditioning coach.

Rem Dawg Remembers

Intelligence Agents

After a trade, when a team plays against a former player, the third-base coach is going to have to change his signs, because the ex-teammate knows them. When a new player arrives, coaches may ask about the signs on his former team and ask about individual players. A team may hire a catcher and then ask for his ideas on how to pitch to his former team-mates. Sometimes it works; sometimes it doesn’t.

At least now baseball is doing something about abuse of drugs by some players; they ignored it for years and years.

Players are always looking for a competitive edge. If that had come through a needle in my playing days, more guys would have used it. There is no question about that.

I have always said amphetamines were more widely used in baseball than steroids. I wouldn’t say it is a bigger problem, but it was more widespread than steroids.

As a sport, baseball wanted to close its eyes because they wanted offense back in the game. Now they’ve got it and they are paying the price for it. It is sad that a spurt of incredible offense ruined some of the legitimate stats in baseball. But baseball should have done something about it because they knew about it.

I can’t blame those who did it because they weren’t violating any of the rules of baseball at the time.

It’s fun to keep an eye on the bench. Watch the manager flashing signs to the third-base coach. On some teams someone other than the manager may be relaying the signs; the manager may not be the best one to give the signs because he may be more predictable with his signs than one of the coaches. If the team is worried that someone on the other side is trying to steal the signs, I have seen situations where a coach or even one of the trainers may give the signs.

In any case there are many different ways to disguise the signs. One way is for the manager to give a sign—let’s say the bunt—and then put a hold on it. From that point on the batter is not looking for the bunt sign, but instead he is waiting for the hold to be removed.

Out on the field the third-base coach gets the most attention because he is the one relaying the signs. The hitter, the base runner, and the opposition are all focused on him.

There is not much to learn from the first-base coach. When a runner gets on, his conversation is pretty basic. He will make sure the runner knows how many outs there are. He’ll remind him about any player on base in front of him—if the guy on second is particularly slow, the coach will remind the runner not to overrun him. And he’ll discuss the depth of the outfielders, which can affect baserunning on a hit.