1954–1958

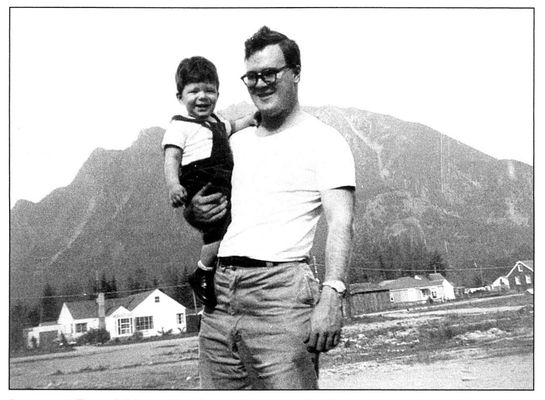

James and Franz bright, Washington State, April 1954

Seattle seems like some impossible Eden. It is certainly the only town that I ever really cared to live in … I can survive in Minneapolis. The students are wonderful. Allen Tate is friendly. It’s not a town to commit suicide in, at any rate (the waterways are always frozen over).

—from a letter to Theodore Roethke

February 11, 1958

February 11, 1958

I just don’t like the Midwest very much. Minneapolis is okay, but I just don’t like it. I think I served my time in such towns when I was a kid … and I was happy with the air and everything else up there near the Pacific Ocean. It is, for one thing, very lonesome here … I always loved the west, and I would like to live and teach there again.

—from a letter to Theodore Roethke

March 27, 1959

March 27, 1959

James, Liberty, and infant Franz returned to the United States from Vienna after a pilgrimage to Thomas Hardy country in Dorset, England. James had been accepted into the graduate program at the University of Washington, and the family settled in Seattle that fall. They lived there until 1957, when James completed everything but the written thesis for a Ph.D. in English literature. In the late summer of 1957 the family moved again, this time to Minneapolis, when James accepted a position in the Department of English at the University of Minnesota.

From Minneapolis, James kept in touch with two teachers at the University of Washington who had become important friends: Theodore Roethke and Wayne Burns. Letters to Burns, his thesis adviser, were mostly concerned with his dissertation, The Comic Imagination of the Young Dickens. He wrote to both men of his difficulty in adjusting to the Midwest after Seattle, though his letters concentrated mainly on discussions of poetry. During this time, James also began an important and lifelong correspondence with the poet and editor Donald Hall.

Seattle

December 8, 1954

December 8, 1954

Dear Mr. Hall:

Thank you very much for your extremely kind letter. Your invitation gives me a chance to send you some things which are pretty rough, but which I genuinely care about. There are three pieces. The theme of each one is very violent, and so I tried to write them as smoothly as I could. However, you will undoubtedly find all kind of groping rough places. So whether or not you’re interested in them enough to accept them, I’d deeply appreciate hearing how you feel about them. On the other hand, if you’re as busy these days as I am, you might feel numb about commenting on the thousands of verses you must get every month. But you will judge.

Sincerely,

James Wright

James Wright

Seattle

February 1, 1955

February 1, 1955

Dear Mr. Hall:

You undoubtedly know the kind of cold letter one can often get from an editor; so you can see how surprised and delighted I was to get your friendly note.

You’re right about the mistyping in the George Doty poem. The lines ought to read:

He stopped his car and found

A girl on the … etc.

A girl on the … etc.

As for the title, do whatever you like. I called it “A Poem About … etc.” only because somebody told me that the fellow’s name alone would make it seem that the prisoner himself was either talking or meditating, at least in the first few lines. Of course, the piece is about the prisoner, and is a speculation by a person who stands outside the prison and thinks about the person within. It might be called “A Complaint for George Doty in the Death House” or something like that. But if you think the introductory words aren’t necessary, then by all means leave them out.

And thank you very much for your extended comments on the poem about the girl’s dream. Your letter contained what is probably the most incredible rejection slip ever seen—the kind of editorial justification which everyone desires, and almost no one gets.

Yes, I went to Kenyon. I’m still trying to resist the influence of that wonderful place. And I was in Coraddi a couple of times, so we were probably printed side by side. I don’t know Mr. Matchett very well, but I’ll tell him you asked about him.

As for biographical material: I’ve gone to Kenyon and the University of Vienna, I’m studying in the graduate school here at the University of Washington, and sometimes feel like a fool (but don’t put that in a contributor’s note). I’ve had a lot of stuff printed in the Kenyon, The Sewanee, Poetry, The Western, and the Avon Book of Modern Writing. Other things are to appear sooner or later, but that is neither here nor there. I just turned twenty-seven, and I have a wife and child.

We consider that we have escaped from the East as from a mad and furious master. But if you ever get to Seattle, our house is certainly open to you and yours. Thanks a lot for writing; and I hope we can keep in touch.

Sincerely,

Jim Wright

Jim Wright

Seattle

June 15, 1955

June 15, 1955

Dear Don,

My father is a little older than yours, but it took me many, many years to come to an understanding of what he is, of what he means in my life. He is not very well educated, you see. He went to school as far

as the eighth grade, and then became a laborer. For something more than fifty years he has been a machinist at a glass factory in Wheeling, West Virginia. What with one thing and another, he and I never had anything to say to each other till, one day at Kenyon, I threw off the atmosphere and hitchhiked to our farm, which is located in southeastern Ohio, about 120 miles from Kenyon. No one was home in that barren, ugly place, a perfect hell of twisted little farms and slag piles and taverns, except my father, who sat looking out a cracked window. It was very strange to me. I felt as though I had suddenly materialized out of the air. For about three hours we talked, and read together, out of the Bible, the only real book, I suppose, he has ever known anything about. The meeting was not spectacular, but it shook me very deeply. I had not known of the man’s existence before. It was like falling in love. Somewhat later I wrote a little poem called “Father” and Mr. Ransom printed it, in The Kenyon Review.

The poem, and the experience of writing it, was curious. Now, although I went through a period in which I produced a great bulk of verses, the actual writing of anything rhythmic has tended to be agonizingly hard for me. Different minds work different ways, and my mode of thinking is slow and laborious. But this particular poem came out with a slightly startling speed and wholeness. I couldn’t understand it after it was done, and showed it diffidently to Mr. Ransom, who genuinely frightened me when he said he wanted to print it. It was the first thing I ever had published in an important magazine, and I sincerely thought it was gibberish. I guess I had seen that business about water and birth, and so on, but I’m sure I hadn’t paid any attention.

Anyway, I’m just leading up to typing out the poem for you. Perhaps this will seem impertinent; but, really, I was terribly moved by the anguish of your letter’s beginning, and I wanted to answer in the best, most dignified way I could find. So here is the poem “Father” which is, I think, a kind of love poem to him, if there are things like that:

In paradise I placed my foot into the boat and said:

Who prayed for me?

Who prayed for me?

But only the dip of an oar

In water sounded. Slowly fog from some cold shore

Circled in wreathes around my head.

But who is waiting?

Circled in wreathes around my head.

But who is waiting?

And the wind began,

Transfiguring my face from nothingness

To tiny weeping eyes. And when my voice

Grew real, there was a place

Far, far below on earth. There was a tiny man:

To tiny weeping eyes. And when my voice

Grew real, there was a place

Far, far below on earth. There was a tiny man:

It was my father wandering round the waters at the wharf

Irritably he circled and he called

Out to the marine currents up and down;

But heard only a cold unmeaning cough,

And saw the oarsman, shawled in mist and ether,

Drifting out of the great forgiving deep.

Irritably he circled and he called

Out to the marine currents up and down;

But heard only a cold unmeaning cough,

And saw the oarsman, shawled in mist and ether,

Drifting out of the great forgiving deep.

He drew me from the boat. I was asleep.

And we went home together.

And we went home together.

Perhaps it’s like that. We get the fog apart for a moment, and we rush through the opening, and find them. And then we look around us, and the whole country is strange and new, and we are men. The whole affair seems to last so short a time.

I’m delighted that your book will be out next year. It will certainly be one of the three or four books a year I can afford to buy. I’ve been thinking a good deal about the style of your poems, and I’ve concluded that you must be one of the few civilized men left in the world—that is, you must take as much delight in great poets like Dryden as a very few other young men can do. Perhaps it is the next swing our language must take. We must realize that the metaphysical lyric, though gloriously demonstrated in the age just past, cannot be re-written a thousand times. Imitators of Donne generally turn into Cowleys and Clevelands. On the other hand, our alternative is not necessarily to reestablish the more rationalistic grace of the heroic couplet—though, as Eliot said in writing of Samuel Johnson (one of my gods, incidentally), that form is far from worn out. Ages do not repeat themselves so closely. We have a chance to do a million things Rilke and the rest couldn’t do. We can be funny and gross and graceful, all of these; but

we can get deeper than the lyric itself. We can bring back into our poetry the rich stuff of drama—not the form of the stage, though that is possible and I am unqualified to write of it or speak of it, but the devices of drama which toughen and deepen poetry through its exploration of point-of-view, personality, and so on. I have written about ten dramatic monologues, and I expect to go on trying. By the way, nobody will publish a damned one of them. The old mossbacks say that we can never equal the lyrics of the first half of this century, and yet they are squeamish about publishing the other tries we make. But this, of course, is just an excited squeak about some of the many thoughts which your pamphlet of verses set going in my head.

I have a very young friend named Robert Mezey who was a good associate of mine back at Kenyon a while ago. He has just been discharged from the army, is twenty years old, and is wandering around Philadelphia lamenting the fact that he has already written himself out. The idea of a twenty-year-old’s saying such a thing was so funny to me, that I thought I’d mention him. He is really one of the most gifted people I know, and has written two or three very beautiful poems. One of them in particular is striking. While he was in the army he had some nervous ailment, and was in a mental hospital for a while. One afternoon he heard a woman weeping in one of the wards; and that so set him off, that after a good deal of labor he wrote a poem called “Dusk Near a Mental Hospital” which is one of the finest and most touching poems I have seen in a long, long time. I don’t know exactly what he’ll do next. He’s thinking of going to Iowa. But whatever he does, he certainly ought to be a brilliant poet. You ought to like him—he is a likeable person, and can write epigrams. (As I told you once, I have an obsessive admiration for writers of epigrams. I’m one of those people who can never think what to say till the party is over.)

I hope the opening of this letter doesn’t offend you. I wanted, and needed, to say something; and almost everything I could think of sounded stupid. There is a time when prose absolutely breaks down.

Yours,

Jim Wright

Jim Wright

Seattle

March 22, 1956

March 22, 1956

Dear Don,

Your letter was splendid, as always. Let me depart from my own usual procedure, and try to answer directly some of your questions and remarks.

Yes, I’ve seen [W S.] Merwin’s new poems all over hell’s half-acre. If I’ve ever mentioned his work to you, it was probably with a kind of half-amused despair. For a long time it was a joke between my wife and me that every time I got a poem printed it would be either preceded or followed by a poem of Merwin’s. The joke was based on the fact that his stuff has got so good it is astonishing. To speak straight, I think his talent is ripening remarkably, and that he will be a great poet. Some objections to his earlier pieces had to do with his concern for technique over deeper emotional effects; but I think he always must have been a man of feeling, for even in the early pieces you find “The Ballad of John Cable and Three Gentlemen,” one of the most beautiful poems I know (and, by God, it appeared in The Kenyon Review right smack dab in front of the first poem I ever had printed!). His range of learning and wit and meter always fills me with admirations, and I should be very pleased to meet him sometime.

I heard from Yale (simply that they received the ms.). Of course, Don, I realize that the field is crowded, and that my book doesn’t have the chance of a snowball in hell. I have pretty well satisfied myself with the expectation of running into a publisher some years hence. I don’t know but what this situation satisfies me best. I have so many things coming out in periodicals; and I write sometimes at such hectic speed (I have to, I have so much else to do), that I want to get time one of these days to go over everything again. As for Auden, he is no doubt one of the best writers of our day, etc.; but I wonder if it has ever occurred to you how much power he has over our generation, as a reviewer, as a contest judge, and as a direct influence. Sometimes I don’t like it. He has many noble things to say about poetry, and many noble poems of his own; but there is also a streak of smart-aleck in him which is easy to imitate, and which, I think, is sometimes too easy for him to exercise. Maybe this is just a rambling restlessness. To tell the truth, I have a great deal more faith in somebody like Louise Bogan, who is certainly not without wit of the most acute kind, but who also possesses a deeper

sympathy for younger people. Both she and Auden spoke here. Auden was entertaining all right; but Bogan was something else. She was a radiant presence. Chatting with Auden, I felt like a punk, which is no doubt what I really am; but talking with Bogan, I felt like an acknowledged human being with something important to do.

Roger [Hecht] had mentioned [Louis] Simpson many times in letters, and has done everything possible (as you have done) to get me to read his poems (which I have done, in complete agreement with both you and Roger). I hope, incidentally, that you can meet Roger sometime. You will enjoy him. I never met his brother, though I have admired him for a long time.

I’m very glad that Thom Gunn took those two poems, particularly “Unborn Child,” which is one of your best. I wonder if Merwin is going to be in that group. Gunn may as well throw the book at those English.

In April and May and June I’m going to have a little spate of poems popping up all over hell’s half-acre. Gunn says the London will be out in about May. In April I’m having a spring song in New World Writing . In the April issue of Poetry I have four new poems. There’s one to appear in the University of Kansas City Review sometime in the spring. And I just heard from Jackson Mathews that he’s going to use three of my translations from the contemporary French poet René Char in a book (called Hypnos Waking) which Random House is supposed to publish on June 4.

Incidentally, you ought to know Jackson Mathews, if you haven’t met him already He was a great teacher here at Washington, and he’s just gone to Paris on a Bollingen fellowship to work on a new edition of Valery’s works. He is a friend of Char (one of the great masters of our time, I think) and is constantly preoccupied with the problem of translating him. Mathews and his wife edited the New Directions edition of Baudelaire that just came out last year. Most of Jack’s poems and translations come out in Botteghe Oscure; but his articles elsewhere, chiefly in the Sewanee Review. I think it was in the Sewanee of Fall 1953 that he had his review of Roy Campbell’s Baudelaire, and in it he set forth his theory of translation, which you would find extremely interesting. (Briefly, it would require an almost inconceivable biological accident for a poet in one language to have exactly the same temperament and technical equipment to translate a great poet like Baudelaire;

hence, the idea is to translate him by parceling out his works to a good number of poets in English who can give single poems sufficient study. This notion might sound fragmentary and odd; but I think it produced a tremendous translation of Baudelaire, probably the definitive one in English.) Well, Jack Mathews works and produces with great energy—criticism, translation, stories, poems—but his productions are nothing compared with the man himself. You ought to know him [ …]

About Bob Mezey: to tell the truth, I’m starting to worry about him. A while ago he wrote and said he and his wife were going to jaunt around the country, and then come to Seattle in March. Well, I answered his letter, but I haven’t heard anything; and now that you say your letter was returned from both Raleigh and Seattle (by me), I’m wondering if the two Mezeys haven’t got stuck somewhere. It’s been snowing like hell all over the country, even in Seattle; and they might well be holed up in Butte, Montana, or someplace like that. Have you heard anything?

J. V Cunningham is coming out here to give a Shakespeare course this summer. It will be fine to have him around. We need some intellect in this community, now that Mathews and Roethke are gone. Among the active writers, [Charles] Gullans is the only effective defender of the classical mind in the whole town. Incidentally, he showed me some new things which are quite fine.

I know I haven’t sent you anything new for a while. To tell the truth, I haven’t even typed much, though I’ve been writing like hell, mostly stuff that isn’t coming off. I can’t say that I feel barren—far from it. But I’m going through some odd stage in which changes, which I don’t understand, are taking place. I don’t want to sound like Letters to a Young Poet, but it’s the truth.

Well, I’ll enclose one brand new piece, of which I am not at all sure. It lies at the moment in my notebook in a final (?) longhand version. I guess this fumbling and searching around is symptomatic. People are ready for books at different times, and I guess I just ain’t ready; because I don’t yet know just what the hell I’m doing.

Please write.

Yours, Jim

Yours, Jim

Seattle

May 17, 1956

May 17, 1956

Dear Don,

I’ve won the Yale prize! Dear Don, I don’t know what to say to you, I am so happy.

Jim

Seattle

August 25,1956

August 25,1956

Dear Dr. Timberlake:

It was very good to have your letter. I’ll be glad if we can keep in touch now and then, not only on the matter of the possible Kenyon instructorship, but also for friendship’s sake.

You spoke of the rising tide of freshmen. I should tell you that whatever college teaching I’ve done (three years of it, with the fourth coming up) has been with freshmen. I’ve taught the greenhorns in the daytime and the adults in the evening. I’ve taught rather basic courses in the composition of essays; others in logic and slightly more complicated problems in rhetoric—for example, we try to explain to the Freshmen just what kinds of meaning are involved when, say, McCarthy refers to Alger Stevenson; and I’ve taught also the third course in our three-quarter sequence—a kind of introduction to the study of literature. Finally, I’ve had a little experience in teaching a remedial course in grammar and sentence structure, and I’ll probably teach another such course in the coming year. It might be useful for me to tell you that I enjoy teaching freshmen very much. Nothing in teaching can give me so much satisfaction as showing students that it is illogical as well as immoral to use the personalities and writings of other men simply as crude material for their own undeveloped sensations. I think freshmen respond more directly and honestly to a teacher in these matters than do the slightly older literary “sophisticates,” who, these days, are often well on the way to corruption. But I see that I’m beginning a pedantic sermon here, instead of clearly telling you what I’ve done and what I like to do.

All I meant by saying I was a little apprehensive about your judgment

of my book was that you were the hardest reader to impress with undergraduate tricks back in my old days at Kenyon. We used to feel—Roger Hecht, Jay Gellens, and the rest—that you read not only as a contemporary but with some of the great and Johnsonian past which insisted that poetry was a serious matter and should not be fiddled away in nonsense. Yet undergraduates are full of nonsense, and nonsense always quakes under the searchlight of the Johnsonian reading. I must say that, what with the intervening years of intense writing and disillusionment with editors, I would rather be called a minor versifier by Johnson than praised as a new Shakespeare by Stanley Edgar Hyman (who, I believe, is a catastrophe in the English language comparable to the bombing of Hiroshima). What I am trying to say can be expressed in words which have been used often but which cannot be worn out: “The irregular combinations of fanciful invention may delight a-while, by that novelty of which the common satiety of life sends us all in quest; but the pleasures of sudden wonder are soon exhausted, and the mind can only repose on the stability of truth.” All that is not to say that I dislike fooling around with language—far from it. But the fooling has sooner or later got to expose itself to the judgment of that larger and more generous common humanity which is more important than poetry, and in vital relation to which the final importance of poetry is, or ought to be, defined.

Speaking of Roger Hecht, he spent a week with us recently. He is working in New York, and seemed in good physical condition—he hadn’t had a fainting spell in about two years. We had a perfectly splendid reunion, with lots of beer and music and conversation. I think he will be writing you soon, if he hasn’t done so already.

I’ve waited till the end of the letter to mention the enclosed poem.7 It isn’t necessary to talk about it, except to say that I had the dream a few nights ago, and couldn’t think of anything to do but work the thing out—I wrote the first version very fast, and the second and final one very slowly. If you think the poem is worth anything, I wish you would offer it to the Kenyon Alumni Bulletin. I don’t know what you thought objectively about Dr. Coffin’s voice in the reading of poetry—I know that it carried a certain twang—but a voice in poetry is not the same as a

voice singing Mozart; and, even if the voice were bad, I should still remember it as beautiful, because it was the first voice I ever heard reading Milton aloud. It had the freshness of the early world; it had the dew upon it.

Please write a note when you get around to it—it needn’t be long—just something by way of keeping in touch.

Yours,

Jim

Jim

Seattle

March 31, 1957

March 31, 1957

Dear Don,

I guess you’ve occasionally wondered what the hell, but you’ll remember that I had that Ph.D. general exam to face. Well, I faced it, and I passed. Now it can be told: next year I’ll be an instructor in humanities at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. From what I hear, and keep hearing all the time, it’s a good place—scholarly as well as vitally creative. Arnold Stein went there (you know him), and there are people like Monk, Unger, Tate, and John Berryman.

Speaking of Berryman, what do you think of “Homage to Mistress Bradstreet”? Just the other day John Haislip (who, it seems, is a good friend of Berryman’s from way back) lent me the poem in its newly published form, and I must say that I was often overwhelmed by it—although two or three times I lost the point of view, and couldn’t even straighten it out with reference to the notes. Perhaps further reading will clarify the argument. In any case, it is in many ways a great poem, I believe. What do you think?

Robert Lowell spoke here last week, and, though he is probably the world’s worst public performer, he certainly is an appealing man. His poems are magnificent.

Philip Booth sent me a copy of his book, and I like it fine—though the frequent compound adjectives in the first part of the book are sprinkled a bit too thick. The political poem (I think it’s “Easter, 1954”) is one of his best, and a fierce and beautiful poem. He has a good deal

of stuff in him, and is going to produce a great poem one of these days, if I am not mistaken. There is a certain uncluttered honesty about his mind, which certainly reminds one of his hero Thoreau.

As for me, my book isn’t out yet. It’s got me terribly skittish waiting for it. It’s worse than waiting for the god damned Ph.D. oral. To make matters worse—much worse—is the fact that, as far as I can tell, I’ve got another book done. Now, I can’t just sit and stare at it. Yet it would be ludicrous to send it to Yale (they have the option on the second book) even before the first one is in print and on the stands. I might hand it over to the tender mercies of Bill Matchett (he gave me a fine reading at one stage of The Green Wall) or Arnold Stein (who has promised me to go over it, and he will certainly cut it to ribbons), but I don’t know what else to do. It’s extremely nerve-racking to me to have the thing lying around inert. The prospect of sending it to Yale in a little while is very frustrating; because it’s obvious that they’re going to reject it, and I’ll have to go through the whole business of finding a publisher all over again. I swear to God one of these days I’m going to give up poetry and go directly in for a life of crime.

As a matter of fact, I’ve written one new poem in a while, and it’s a political poem of a sort.8 Well, what the hell, I’ll enclose it. It’s got its prison scene, and a sort of submerged surrealistic hymn in the second part.

You haven’t written for a while, and I don’t blame you, but I hope to God you are well, and that your family is well, and that you are getting your work straightened out the way you want it.

Please write soon.

Yours,

Jim

Jim

Minneapolis

September 13, 1957

September 13, 1957

Dear Ted,

We’ve been here about three weeks now. I might say that we’re reasonably settled, though there are still a few things to do. The neighborhood

is comparatively quiet. There are several kids of Franz’s age; so we’ll live.

Mr. Hornberger, the head of the English dept., greeted me pretty hospitably, and I met William Van O’Connor, who was quite cordial. For the rest, the building that houses the English dept. is in a hell of a mess, because of redecoration or painting or something. At any rate, I now have an office, and there I have occasion to write a poem:

My office-mate

Will be Allen Tate,

And if I get on his nerves

It will be no more than Hornberger deserves.

Will be Allen Tate,

And if I get on his nerves

It will be no more than Hornberger deserves.

We’ve made friends with some cordial people from the humanities dept., but, for the most part, the town looks as socially bleak as it is physically attractive. I expect that my chief resources through a cold winter will be Dickens, footnotes, teaching, and whiskey—the last of which is moderately priced and easily available, thank God.

I hope you don’t mind my mentioning this, but it has been on my mind: I remember our talking one time about your new book, and the problem of reviewing it for Poetry. I don’t know for sure that you would take to the idea of my writing a review, or whether Rago would agree, or how I should go about writing him, or what. If you have any thoughts on the subject, would you tell them to me? I think I could do a good job on it. At least, I would do my homework. However, it’s up to you, of course.

Lib has a turkey in the oven, and it is about ready to emerge. I guess there are compensations for leaving Seattle. We could have had turkey there, however, and I’m not sure whether I like this place or not. I think I don’t. But that’s neither here nor there.

We hope that Beatrice is better, and that you are feeling well.

I don’t know what sort of correspondent you are, but I’ll soon find out.

Yours,

Jim

Jim

Minneapolis

October 24, 1957

October 24, 1957

Dear Ted,

I see by the return address that you’re hospitalized. Well, you sound good in your letter. Get a good rest; and, if there’s anything you want sent to you, or anything you want done, don’t hesitate to give Lib and me the word. I can’t think of any use for our phone number at the moment, but in case you want it for anything, it’s FEDERAL 6-9829.

Just as soon as I got your note, I wrote an explanatory letter to John Palmer at Yale Review about your new book. He hasn’t had time to answer yet, but as soon as he does I’ll tell you what happened. The same evening, I wrote to your publisher in London, and ordered a copy of the book. I asked them to send it to me pronto, because I want to see it soon. I have my copy of “The Waking,” but I need to see the entire book in one piece, since one of my main points would have to do with the recognizable coherence of development from the early pieces to the most recent ones.

By the way, in your earlier letter you said you were going to send me the new piece you had been working on. From your description, it sounded pretty exciting. May I still see it?

There’s a fellow here—named Morgan Blum—a smart man and really a sweet guy—who is thoroughly familiar with your poetry, and who has a really sensitive knowledge of poetry in general.

In your note, you asked if Minnesota wants you to read here when you come east. Here is exactly what I did: I broached the matter to Theodore Hornberger (head of Eng. dept.), who said that such a reading on short notice was probably out of the question, because lectures for this year had already been arranged last summer; and that any break in this routine schedule would have to be made through the chairman of lectures and concerts (whoever he is), and that this chairman is difficult to persuade. HOWEVER—note well—Hornberger asked me to get Allen Tate’s advice. Today Allen told me that, though there probably isn’t any chance for a reading here at the university itself, he may be able to arrange something at the Walker Art Gallery. He said that, of course, a reading at the Gallery—where he has arranged readings for Spender, Viereck (I think he said), and others in the past—would not be able to pay two hundred dollars. Finally, he told me to hold my pants on while he found out what could be done. This is the

extent of my information. I will write you immediately as soon as I see Allen again, if he has learned anything.

As for myself, I am laboring my nuts off teaching, roaring and raging like Billy Sunday at my humanities class. I’m teaching Rousseau, whom I hate—I think him sentimental, cold, cruel, dishonest, a fucking fascist, and a shit in the lowest sense. However, I have also been teaching Hobbes, who is such a magnificent writer that the students like him, and I love him. If he is a totalitarian, then he at least is honest about it. And that prose! “The life of man is solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” I can hear the old son of a bitch snorting with laughter and gusto as he wrote that sentence, certainly among the most beautiful I have ever read. It never fails to send a shiver up my back.

I wish I had some new jokes to send you, but life among my colleagues has been singularly humorless. It’s a hell of a note when a man has to make up his own jests and smirk at them in empty rooms at the humiliation of no audience.

Excuse the obscenity, Ted, and please get a good rest. Lib says that whether or not a reading works out here, she hopes you can stop to see us, and I hope so too.

Love,

Jim

Jim

Minneapolis

November 30, 1957

November 30, 1957

Dear Wayne,

Do you think that poetry is some kind of a disease? It is very early on Saturday morning, and I have just got a thing done after wrestling with it, in the worst way (with headaches) for many months. This time, I found that I had wasted a full page on something that I could have said in a single little phrase of three words. So this morning, I said it in a single little phrase of three words, and rebuilt the whole thing around them. This paragraph is just to illustrate what has happened to me and words during this whole quarter. It seems that the only thing I can actually write down on paper is verse. I rise early and read like hell—all

kinds of nutty, sinful stuff: Shaw, Tolstoy, George Gissing, Shakespeare, Sterne: and these are my Dickens critics!

What I mean is that I’ve been through the Dickens shelves in the Univ. of Minn. library (my God, you ought to see them, they would startle Dickens himself), and I’ve even looked through the whole Dickensian, and yet the only useful critics I can find are all of them utterly strange and unlikely. I know you won’t mind unorthodox critics on Dickens in my essays (and when, Oh for Christ’s sake, when will those essays be written?), but—well, reading such stuff in line with my own obsession about Dickens is not going to make me a very good Victorian scholar.

Look, I have an important (to me) question to ask: as far as I can find, there is no standard critical edition of Dickens’ novels. Do you think it will be all right if I identify my quotations from Dickens simply by noting the chapter number (of the appropriate novel) just after the quotation right in my text itself? In the first place, there is, as far as I know, no textual problem in Dickens, as there might be, say, in The Vision of Piers Plowman. Second, I see more and more that my little book on Dickens (I’m starting to think of that little book with affection, even though it has no physical body yet) as a real critical job, as distinguished from the kind of genuinely scholarly work that John Butt and Kathleen Tillotson are doing. Third, in order to substantiate my pitch about the nature and operation of Dickens’ imagination, I will probably have to quote extensively, and I hate the clutter of footnotes. Well, to repeat, can I just quote a passage, and then refer to the chapter number?

I also found the perfect image of the Dickensian imagination in Don Quixote. I don’t know why it never occurred to me before, but do you remember that comic passage where Sancho tells the story of the man ferrying the hundred goats across the stream one by one (with full detailed description of each goat and each ferrying trip) and is interrupted by Don Quixote with the demand that he say simply that all hundred goats were ferried across? The joke is that a story-teller ought to get to the point. But Dickens is backwards from this. If we conceive his plots as the “point,” then he never gets to it; and, in the process of evading it, he forgets, and makes us forget, the other side of the stream, and he forgets what he wanted to do there; he is so delighted with his goats—the brown goats, the green goats, the old goats without beards, the young female goats that need shaves, the ferryman’s plastic leg,

and, perhaps most exciting of all, with the ferryman’s second cousin’s sister-in-law’s goiter. Anyway, I have conceived the grand strategy of retelling the story as I found it in Don Quixote and using it as a critical metaphor. What do you think?

Herbert Read was here and I got to talk to him again, though, of course, this time I was more considerate. There was a real honest-to-God reason for being considerate this time. You won’t believe it, but I swear it’s the truth: Herbert Read and Billy Graham arrived at the Minneapolis Municipal Airport at the same time on separate planes. Having been informed that a famous Englishman had also arrived, Billy Graham strode (you know, strode, like Eisenhower in Time Mag.) over, smacked Read on the shoulder blades, and welcomed him to the Twin Cities.

So I simply told Sir Read (this is what Billy Graham called him: well, I told you you would think I was lying) that I was engaged in preliminary work for an essay in defense of Little Nell. He smirked (I don’t blame him; wouldn’t you smirk? I would). Read and Allen Tate are old friends. By the way, Tate (who is my office mate—I can’t keep it from rhyming) has turned out to be an extremely nice guy. I’ve always liked his poetry, and he himself is a good man.

I feel in an idiotic position. In Epoch magazine, a guy favorably reviewed my book (which is okay), but he used it to flog the San Francisco writers. Now, some of the San Francisco stuff I like (Ginsberg’s “A Supermarket in California” is a very beautiful poem), and some I don’t like. However that may be, I don’t want to be used as a polemical weapon either for or against anybody. Can you imagine a more farcical position to be in?

I just remembered another wonderful Dickens thing (disguised) which I found: in one of his essays on art (I’ll look it up later), Tolstoy tells us how to read a great book. The whole passage is striking and true. No wonder Tolstoy liked Dickens so much. Incidentally, your seminar method of finding the true Dickens criticism is working (I hope). I just read the great novels, and the great novelists on one another (like Gorky’s Reminiscences of Tolstoy, a book by God that would make your hair stand up on end and dance Dixie), and, if those writers are post-Dickens, they make some comment on him sooner or later. Sometimes, as in the case of Sterne and Cervantes, they comment on Dickens even before he was born. Has anyone ever studied Tristram Shandy as a work of literary criticism? It’s loaded.

I’ve exchanged a couple of letters with Larry Lawrence. He was depressed the first time, and I tried to comfort him, but you know how that sort of thing goes. Larry has a morose streak which is all but indistinguishable from his humor, and one never knows what the epigram will amount to. I would like to tell him, of course, that the one fortypage chapter out of his novel is the best fiction written in America in the past ten years; but you know that he would just think I was trying to make him feel good; and the inhibition makes things impossible.

I was interrupted for a moment, and lo and behold it was Glenn Leggett on the phone. It was good to hear his voice. I told him, of course, the very thing I would report to you: the people in this town have been nice to me, and I hate the town like death. I am so unutterably miserable in the midwest that I am numb for all of every day except in the very early morning hours, when I read and write. I’m afraid to speak of this, yet I must. I’m afraid, because I can’t seem to make anyone understand the dreadful, practically subconscious, effect that the landscape of a town makes on me. I was so happy in Seattle that I almost felt sinful about it—a sure sign of happiness. I think often how I would like to ask Leggett or Heilman to let me come back to Washington; but I can’t write the appropriate letter, because I realize that they would say no, that they would say I am just suffering from the graduate student’s lonely neurosis during the first year away from the womb of his native graduate school. So it seems impossible to escape. Will you please keep this in mind, Wayne? I’ve not said this to anyone, because it sounds so silly in words: but—everything I write in this town seems a fight against Nature, and I’m sick of fighting Nature. I fought it till I escaped from the Ohio Valley, and I was in harmony with it in Seattle. I achieved a great amount of work there, and I could do it again. I’ve written some verses here; but I always have the feeling that I’m trying in despair to nourish myself from within in defense against this exile. During my years of study at Washington, I labored with joy, and I produced, I got my work done. I did well, and in addition to graduate work I wrote a book. Yet it seems that my simply having attended Washington was a crime for which I have to be punished by exile. Please don’t laugh at my melodramatic tone. These are the terms in which my life presents itself to me all the time.

But I’m afraid there’s little point in talking about this. I go on lamenting to myself about it continuously. There have been a couple of

times in my life when I found my surroundings unendurable, and I revolted against them. But in every case I planned for a long time. Up to my fifteenth year I abominated the Ohio Valley, and at that time I hated it so that I had a nervous breakdown. In the hospital I decided that I would not die for any thing or any place, not even for love, not even for guilt. But I didn’t run away when the hospital released me. No. I returned to school, studied Latin and mathematics very hard for two years, and then went to the Army which, I knew, would pay me for going to school. The GI bill paid for school till my last year, but according to my correct calculations I had done well enough in school to receive a full scholarship just at the time when the GI bill ran out. And now I find, after half a lifetime of labor, that I’ve got to go through a similar process. I’m not sure of the strategy yet: but I’m going to work like hell and produce everything I can, and then I’m going to apply at Washington again. If I’m rejected, I’m thinking of getting out of the academic world altogether, and coming back to Seattle to work at Boeing or something.

Please forgive me for running on like this. But the subject is an obsession with me. It twists and turns grimly at the center of my brain, like the axis of the planet Earth. And I am getting sick of spinning on an ellipse through the dark. The hell of it is that I’ve now got a whole set of new poems on this subject of exile and revolt, and that I’m pleased with them, and that I don’t know who the hell would publish them. They’re really Romantic, you know. I read just one of them aloud to Lib, and she was so shocked that I’ve just kept the others in my notebook. If she finds them intolerable, I don’t know what the hell the editors would think. I am getting absolutely furious at the state of things. Here I am, almost 30 years old, half-dead, with language roaring around like mad in my skull, and I ought to be doing the work of joy, but here I am, writing attacks and angers and laments. The ghosttheme, or attitude, has taken hold of me two more times, and I’ve got appalling poems on it.

I think I’d better control myself, before I go haywire. Even now I don’t know how you’re going to make coherent sense out of this letter.

To get to something perhaps amusing, I’ve been corresponding with my best student at Washington, a talented young person (God, I feel about a thousand years old) named Miss Sonjia Urseth. I sent her a copy of the new poem called “All the Beautiful Are Blameless,” and

asked her to give it to you. I also wanted her to meet you. It develops that she has tried about fifteen times to get an appointment with you, and that she hasn’t been successful. I hope she succeeds pretty soon. I think she needs to talk very much with someone like you. You don’t mind, do you?

Please write soon, and let me know about the question on quotations from Dickens.

Season’s greetings.

Yours,

Jim

Jim

Minneapolis

December 15, 1957

December 15, 1957

Dear Beatrice and Ted,

We’ve heard through the inevitable scuttlebutt that you’re both well, and this makes us happier than we can say. I’m getting ready to send you two or three new poems. You don’t have to feel that you need to comment on them, but I want you to see them nevertheless. I have some news which will make you proud, I hope: Ransom strictly enjoined me to keep it secret till the Kenyon Review appears in early January: I’ve been awarded the Kenyon Review Poetry Fellowship for next year. I’m going to spend six months of it in Seattle (Fall and Winter quarters of next year) … I trust by this time that Mr. Stange from the English dept. here has written you about a possible reading in the Spring. From the way he talks, the university would be prepared to make you extremely welcome. I hope this was the sort of thing you had in mind when you dropped the remark (in a note to me) wondering whether or not they would like you to read here. I think I’ve told you that Allen Tate has been very kind to us. He certainly seems to think you’re the Heavyweight Champion of contemporary American poetry.

This is the 15th. On the 18th we’re driving to Ohio to visit parents for the vacation. Among other things, we’re going to visit Pappy Ransom at Kenyon. He seems awfully lonesome there, and no wonder.

Ted, with the poem that you sent, you mentioned a long letter you had written me; but I haven’t received it yet.

I’m still plugging at the proposed essay which we’ve discussed, but I haven’t come up with anything yet. I just had a new idea, but I’ll let it simmer till I have something real to offer. Meanwhile, to defeat the inescapable human tears of things, let us all turn to Julia A. Moore:

The winter will soon be over,

With its cold and chilly winds.

It is sad and dreary ever,

Yet it’s dying, free from sin.

Now the springtime is coming,

Ah, yes, will soon be here.

We will welcome in its coming

In this glad new year.

Love, and laughter too, from all four of us

(we have a monstrous black dog),

Jim, Lib, Franz, and Duncan

(we have a monstrous black dog),

Jim, Lib, Franz, and Duncan

Minneapolis

December 17, 1957

December 17, 1957

Dear Gege and Lloyd,

Here we are at the University of Minnesota, drawn back to the midwest as by some evil spell. The town is unspeakable; but the people are okay. I teach English (advanced composition) and Humanities (damned near everything from Alexander Pope to Ray B. West Jr.). Tomorrow morning (Dec. 18) we’re driving to Ohio to visit families and revisit the idyllic scenes of childhood. I feel as if I had swallowed ratpoison, and were irresistibly seeking to quench my thirst at the fount of nectar, the Ohio River … Anyway, now that we’ve learned what cities are like, I intend to go back to Seattle after the war … We hope you are well, and that your child is strong and happy. We’re just about sure now that Lib is again pregnant, which is one natural joy in the midst of

Minneapolis. We’ve got a dog, a great black monstrous puppy which is driving Lib nuts, but which is actually quite charming. Lloyd, I wish that one of these days you’d send me your brother Howard’s address. I’d like to correspond with him again … And please write.

Yours,

Jim, Lib, Franz, Duncan, and (potentially) Marcella

Jim, Lib, Franz, Duncan, and (potentially) Marcella

Minneapolis

February 1, 1958

February 1, 1958

Dear Wayne,

How marvelous that you should have sent those 2 books at once, without any question! I hereby take the Pickwickian oath that I will guard them with everything except my life. I will even guard them with my honor. (My God!—“guard” and “honor” in the same sentence, even as a joke—I read and liked Cozzens’s Guard of Honor in almost exactly the same way that I read and liked Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White. They were both entertaining yarns (I use the word “yarns” deliberately—sometimes you can see a good “yarn” on TV Some science-fiction writers write good “yarns.” etc.) written by extraordinarily clever and almost totally unimaginative prose-stylists. The best example of the TV yarn-type thing is the Alfred Hitchcock program on Sunday evenings. Do you remember the protagonist in Invisible Man eating the candied Carolina yams in the cold winter morning, and suddenly, in the snow and the bleakness, swearing that never again will he be ashamed of things that he likes? Well, he liked yams, and he ate them; I like yarns, and I read them or watch them on TV Wilkie Collins wrote yarns; James Gould Cozzens wrote yarns. I read one of them, and I liked it. But I won’t read By Love Possessed. The sociological controversy over it makes it probably impossible to read it. I mean it, not Time’s review of it (the greatest detail in this superbly written review was the one about Cozzens preparing to write by sitting alone and picking his nose—this is supposed to show that he is not one of those horrible escapist, maladjusted experimenters, but a classical realist)—not even Irving Howe’s. Both reviewers agree that in this book Cozzens has gone “all out” and tried to produce a “major work.” It’s exactly as

though the scriptwriter of the TV show Wyatt Earp had, with a straight face, announced between the commercial and the first scene that in tonight’s show he had labored carefully to present the public with his masterpiece, and concluded his announcement with “Yr. most obedient, humble servant.”

If and when you get time to write me a note (and it need be only a note), will you tell me, just for convenience, exactly when you are going to need the 2 books you sent me? If you’re teaching Dickens next quarter, I of course don’t want to deprive you of two crucial books. This is my plan: though I am halfway through a rereading of Pickwick, and have taken exactly thirty pages of notes, I will suspend that job and immediately begin a careful and thorough rereading of Forster. On most week-days I work at least 3 hours in the morning on Dickens, and I find that I can read, reflect, brood, and jot my way through about 50 pages in 2 hours. The Forster will not take as long as you might think; because I’m making careful notes only on the early part of the book, the part that is immediately related to the first six novels, Pickwick through Chuzzlewit. Absolutely as soon as I finish, I’ll insure the book and send it back to you. Then I will go through the Ford in the same way Meanwhile, I’ve decided to order Ford from the publisher, and will pay for it somehow. Every time I get a check of any significant size from an editor (poesy rears its ugly phiz), we buy a washing machine. (The basement of this house now contains about ten washing machines.) If I ever again, however, have an appreciably large clutch of pomes [sic]9 accepted and paid for, I am about decided to use the money on Dickens alone. It is time I started my own Dickens library by seriously securing the basic works. I need things like the Ley edition of Forster, Ford, Surtees, Egan, the new Butt and Tillotson (which I’ve ordered), a file of the Dickensian (God knows where I’ll get one, or why), and (perhaps on the Judgment Day) a complete Nonesuch (I’m afraid I’d have to knock over a bank in order to get the money for that).

As you can see, I’m moving steadily, but I hope you don’t mind my moving slowly. Everything depends on my arrogant confidence that I can write like hell once I get actually started. My having mentioned, both to Hornberger and to you, my hope of finishing the dissertation during the time of the poetry fellowship is beginning to frighten the

hell out of me. What if I don’t finish it? And, even more troublesome, I wonder why I’m anxious. I shouldn’t care. Have I got job anxiety? No, by God, I can still say I don’t really care whether I keep a job here or not (though I like the place pretty well). It must be this God damned catathymic compulsion I suffer from. (Yes, I found out its name. I used to think it was the Muse.)

There is a beautiful new poem by Allen Ginsberg in the current issue of the Partisan. The only thing wrong with it that I can see (it’s a catalogue of the attractions of Mexico, and they deliberately invert the typical tourist attractions listed on travel pamphlets) is the line “Here’s a hard brown cock for a quarter!” That’s just a straight commercial.

Speaking of Ginsberg, there was a curious affair: in the mag. Epoch, my book of poems was reviewed by a man named William Dickey. He liked my book, and I was flattered, of course. However, I soon noted that he wasn’t reading my book at all. He used it as a weapon to clout the writers of San Francisco. You know the pitch: the SF men are irresponsible, ill-adjusted, immature, romantic, paranoid, technically inefficient, etc. Now here, he says (you can see him taking it dramatically out of his pocket) is a poet who is “responsible.” Me, for Christ’s sake. Now, look, I don’t give a damn what a critic does, but, man, a book is a book. Even a bad book is a book. It’s not a pick-handle with which to thwack the enemies of the Lord of Hosts. Anyway, recently I heard from Jerry Enscoe, who read Dickey’s review, became furious, and wrote Dickey a harsh letter. The two are now corresponding, and neither will yield an inch. Jerry asked me what I thought, and this is what I think: I believe that gangs are evil, and that they endanger art. Gangs as such are bad, even if one gang happens to be headed by Kenneth Rexroth. The insane irony of the affair is that both sides are victims of the essential evil which each applies to the other and neither can see for himself J. Donald Adams is the paid whore of advertising, but it is not money which makes him bad, it is his losing his identity in a gang. Kenneth Rexroth is nobody’s paid anything, unfortunately; and his fury and anguish are understandable. But as a critic he is useless; he doesn’t read the work, he distracts you from it. From the viewpoint of either Adams or Rexroth, it is impossible to see what really matters: things like the fact that, in “A Supermarket in California” Ginsberg has written a musical lyric of great delicacy and tenderness. Now, who the hell would associate delicacy and tenderness with Ginsberg? And from

the viewpoint of either Adams or Rexroth, it is impossible to see that, say, Anthony Hecht (who is supposed to be a perfect counterfeit, the very self and voice of the poet-in-the-gray-flannel-suit piddling with words) has written, in a poem called “Christmas is Coming” (in his book A Summoning of Stones), an anti-war poem of really dreadful depth and power.

I ramble. Please write a note. The mimeographed type on this sheet (which you can see, inverted, above) is a list of what I have published since our arrival here. I thought you might want to see it. Thanks again, very much, for the use of those 2 indispensable books. Love to Joan.

Jim

Minneapolis

February 11, 1958

February 11, 1958

Dear Ted,

How horrible that I should have waited so long to answer! But I’ve been running and bleeding like a Dickensian criminal with his head pulled off. I work like a son of a bitch for at least three hours every morning before daylight—on my thesis. It is absorbing. And my teaching schedule this quarter is such an exciting one, that I get wildly lost in it almost every day. Do you remember Falstaff’s description of Justice Shallow, when that old fart had ranted and danced in the brothels near Lincoln’s Inn Fields fifty years previously? “And when ‘a was naked, ’a looked for all the world like a forked radish, with a head fantastically carved upon it with a knife.” I jot down things like that all day and all night.

You know, it must have been two months ago, at least, that I wrote to Secker & Warburg with the address that you gave me, in order to get a copy of Words for the Wind. It hasn’t arrived yet; and, since English publishers are always prompt, I can only figure that you gave me the wrong address. Can you give me the right one? The notion of writing an essay on it still quivers in the thin air of possibility, and I imagine you’re pretty disgusted with me by this time—all that bragging, and still no essay. But maybe one will come up soon. Please don’t be cross.

I’ve corresponded a bit with Mr. Heilman in London. He seems well—having a good time. Like a fool, however, I mentioned to him my hope of returning to Seattle some time; and he answered, directly and clearly, that as far as he was concerned graduate students should never return to the scene of their crime (the place where they took the work and the degree), and that I absolutely could not go back to Washington. This was really a sharp shoe in the gut; but there is nothing I can do about it. Seattle seems like some impossible Eden. It is certainly the only town that I ever really cared to live in. Apparently, this is just what Mr. Heilman thinks is wrong with my living there. As I get it, the idea is that you are not supposed to like the place where you live too much, because your liking it will somehow destroy you. It sounds almost like Jeremy Bentham’s viciously sarcastic definition of the principle of asceticism: an action is to be judged morally good in so far as it causes the greatest amount of misery among the greatest number of people. But argument is vain. Mr. Heilman will not be moved.

And I can survive in Minneapolis. The students are wonderful. Allen Tate is friendly. It’s not a town to commit suicide in, at any rate (the waterways are always frozen over).

I should mention (unofficially—I am the most unofficial man in town) that Bob Stange seems to have given up arrangements for your reading here, because of confusion. I haven’t talked with him at length, but he said in passing something about your agent’s writing to different places also, and his (Stange’s) not knowing how to make arrangements. Allen Tate, however, keeps telling me that the Walker Art Gallery here would probably like very much to have you; and, since you’re going to be in this part of the country in March anyway, it is my opinion (which nobody asked for) that the Walker would be a good arrangement. At any rate, I hope things work out. It would be magnificent to see you again. I myself feel that I’ve screwed things up more than I’ve clarified them; but I always feel that way.

I’ve got what amounts to an invitation to Yaddo for this coming summer; but I’m not going to take it this time. (There may never be another chance, but I can’t help it.) I plan to sweat over Dickens here in Minneapolis and, unless unforeseen difficulties arise, come to Seattle in the Fall … Also, an extremely crazy and improbable thing just happened: I got, by God, a very cordial “fan” letter from Randall Jarrell at

the Library of Congress. He said some nice things, and he said them very graciously. He also asked about my recording some stuff for them, which I will do when I get the time.

My second book is “done” though it hasn’t yet received the proper stripping away of punk poems and junk (it contains about fifty pieces, and I want just thirty, and this time By God I’m going to have just what I want or else I won’t publish it). The University of Minnesota Press is reading it at the moment. Yale University Press rejected it, as I knew they would do (though they just told me that The Green Wall is having a second printing). I would like to have some nice publisher do a nice pretty plain job on it, and I want it to contain exactly thirty tough, stripped, cold, furious pieces. As usual, I’m having a hell of a time (or I’ve had a hell of a time,—I haven’t even looked at the damn manuscript for about two months) deciding just exactly which poems to cut out. I need help. Maybe the editor here at University of Minnesota Press can help me, if they want the book; or maybe a couple of other people would help. The tentative (and permanent, unless the prospective publisher—maybe I’ll find him in heaven—objects) title is The Lamentation of Saint Judas.

We’re buying a house, and Lib is getting fat. With child.

Please write, and please send me the right address of Secker & Warburg.

Love to you and Beatrice,

Jim

Jim

Minneapolis

February 14, 1958

February 14, 1958

Dear Ted,

Heaven knows you have enough verses to read; but I thought you might care to see the enclosed. It’s about the fifteenth version of an elegy for Philip Timberlake.10 Perhaps you remember last year my wanting to talk to you one late afternoon, and your driving me over to a joint near Green Lake for some whiskey. I had just heard of Timberlake’s

death in rather a startling manner (I had just received a letter from the Kenyon people, asking me to write an obituary for him; and I hadn’t even known he was ill).

I’ve got to hurry to my Shakespeare class soon. Please write.

Yours,

Jim

Jim

Minneapolis

March 12, 1958

March 12, 1958

Dear Ted,

You mustn’t feel bad about having to cancel your tour. Certainly everybody in Minneapolis who had anything to do with the series of readings expressed only concern that you should follow your doctor’s orders very closely. Chas. Gullans once told me that the people in this city are very civilized, and he was right—they are real human beings. Of course, many people were looking forward to hearing you, and I’m very sure that they will lose no opportunity to hear you in the future, wherever and however they can. The main thing, everyone agrees, is for you to take it easy right now.

I have this little suggestion—or rather request—to make. You know, the series of readings here is supposed to feature about four internationally known poets like you and Tate and Berryman, and then the last reading will “feature” two young punks—Reed Whittemore and myself. (Of course, Whittemore is not a punk, but you know what I mean.) I wonder if you would object to my reading a couple of your things—and would you have any preference? As a matter of fact, it’s ironic that I should grow suddenly pious enough to ask your permission, because I’ve already given a small reading here (to the undergraduate English club, you know the sort of thing), and I read two of your poems to them. Beforehand, Bill O’Connor (really a sweet man, with a perfectly adorable wife with whom I am madly in love) pointed out that, though the undergraduates here (they are extraordinarily bright) know about your stuff, they are not really very familiar with it; and so he agreed that their education demanded a bit of Roethke. I said “Elegy for Jane” to them (with single poems by Yeats, Hardy, and W H. Davies) at the beginning. After a coffee intermission, I gave a little snotty discourse on the epigram, and I couldn’t resist saying “Academic.”

The audience at the Walker Art Center will be a good deal larger and more widely read; so may I read something of yours? And, if so, what? I have favorites, as you know, but since you won’t be able to come here I thought you might have planned something special. What do you think of my reading a short poem from Open House (I still think that whole book ought to be reprinted), one from The Waking, and then a new one? If you think this would be all right, would you please send me a copy of one of the new ones? One that you especially like? Please don’t hesitate to say if you think I shouldn’t read anything at all. I really want to do this for the sake of the citizens of Minneapolis, who, as I say, are very civilized, and who, I am certain, would be delighted at the chance to become more familiar with your poems. Please let me know what you think, how you feel, etc. I have to give my reading on May 7.

I know how terribly hard you labored a few years ago—working at four jobs, and so on—but you say “look what it got me.” Surely you must be aware of the irony in that statement! But I won’t go on. I’ve never directly told you what I think of you, because I’m afraid you would think I am turning you into a father. I swear I never have thought of you as a father. Will you be insulted if I tell you that I and all my friends who are knocking and thumping around, trying to write true poems that are well-made, regard your work as an absolutely solid achievement, the indestructible evidence that in the nineteen-fifties and sixties there was at least some lyric poetry written in America that was great enough to nudge aside the Englishmen of the seventeenth century? I don’t have a single intelligent friend who doubts this. I myself feel funny about writing it down on paper. It’s as though I were reminding myself that I am breathing, or that I am happy, or that I just won a fist-fight. But to love the work of a great lyric poet is not the same as making a papa out of him. Do you know what I mean when I say that I always think of Ben Jonson, Thomas Hardy, and Catullus as my contemporaries? If they are “dated,” then man is also dated, and I happen to be a man. Well, I am running on and on.

One day soon I’m going to send you a new poem, which has caused me furious work for about six months. It began as a little piece in heroic couplets—about ten lines long. Then it grew a bit—still in heroic couplets. Then it grew still more—and I shortened some of the lines. That version is the one which Allen Tate is going to discuss with

me this afternoon (it’s the first time I’ve asked him to go over a poem with me). But last evening, I got to fooling around, and I, so to speak, fell into the middle section of the poem, and thrashed around and broke it all up and threw pieces out the window, and I wrote a sketch, appallingly Biblical and wild, for that middle section. Either I’ve written my first good poem, or else I’ve produced a piece of pompous balderdash. I honest to God don’t know. I’ll send it soon. Love to Beatrice and to you. Please let me know about the reading.

Love from Lib,

Jim

Jim

Minneapolis

April 3, 1958

April 3, 1958

Dear Mr. Lynes:

Your note of March 27 filled me with pleasure and gratitude, and I know you’ll excuse my waiting for a few days to answer. As I told you in my previous letter—which contained the notes for yourP&O column—I had just reached the point of retyping and retouching the whole manuscript of my new book; and I wanted to be sure that I could finish the job fairly soon. I now know that I can do so; and I’m almost certain that I’ll be able to mail the manuscript of The Lamentation of Saint Judas to you on Monday, April 7.

I think I should like to send the book directly to you, if you wouldn’t mind passing it on to Miss Elizabeth Lawrence. It was especially kind of you to mention my request to her, for I know that you are very busy in your own right. As soon as I send the manuscript, I should like to write a note to Miss Lawrence. I want to explain, as briefly and clearly as possible, what I have in mind by the arrangement of the various parts. Furthermore, there are four or five very detailed and specific questions I want to ask her. I hope she doesn’t mind. The questions have to do with the title of the whole collection, and with a few final revisions of phrase and punctuation.

And, as I said before, I am quite aware of the special problems which the most noteworthy American publishing houses have to face, as far as poetry is concerned. A nation produces its literature first of all

through its individual workmen; but this distinction is chronological at best. The whole literature—which I should understand as that strange and unique fusion of the individual’s eccentric contribution and a deeply vital tradition—is, in the highest sense, a creation whose achievement and meaning are shared among people who write and people who read and listen and people who provide occasions for the writing, the reading, and the listening. This is one sense in which all great art seems dramatic. I think it is the plain sense of Whitman’s remark—so much deeper and more complex than perhaps he himself understood—that to have great poets there must be great audiences too. Maybe Americans aren’t writing “great” poetry at the moment; but, in any case, it won’t be written without the human civilization which gives its occasion and defines its meaning. That kind of civilization—simply a free tradition—is the problem of everybody who cares about life at all. So your difficulty is mine too. As you can see, I’ve been reading Edmund Burke. Please excuse my long-winded garbling of his style. I’m grateful for your willingness simply to read the manuscript, and I’ll send it soon.

Sincerely,

James Wright

James Wright

Minneapolis

April 7, 1958

April 7, 1958

Dear Miss Lawrence:

Mr. Russell Lynes has written me a note about his telling you of a manuscript which I have completed. It is a second book of poems, and its tentative tide is The Lamentation of Saint Judas. My first book was The Green Wall, winner of the Yale Series of Younger Poets for 1956 and published by the Yale University Press in March 1957. That was just a year ago; but I had been working on Saint Judas for about a year before The Green Wall was published. The present version of the new book is the result of a series of ruthless excisions and changes which seem to me fantastic. In any case, it is stripped as bare and direct as I can make it, I think.

My request to Mr. Lynes—that he tell me whether or not I might

send the book to Harper’s—was not quite so naive as it might have sounded. I know that even the most solidly established and distinguished publishers in the United States cannot afford to publish much poetry. I guess this fact is just part of the general democratic struggle toward civilization that we all share, whether we like it or not (I happen to like it—after a year of study in Europe, I got miserably homesick). On the other hand, I was aware that publishers like Harper’s are consciously—more acutely than I am, certainly—trying to solve the problem of making poetry available. That awareness gave me the courage at least to ask if I could send the manuscript. I have no illusions about its easy acceptance. (As a matter of fact, I think I should be really shocked by surprise.) But your very willingness to read the manuscript is marvelous, and I am more grateful than I can say. This morning I am sending it by parcel post to Mr. Lynes, who has promised to hand it on to you.

I hope you won’t mind if I make a few remarks about the manuscript. They might possibly be helpful:

I’ve sent you the fair copy. Please excuse the fact that the type on some pages differs from that on others. I had to prepare the final version of the manuscript at different places and different times. It’s probably silly to mention this, and yet it’s just the kind of thing that, personally, I would find very nerve-racking. Anyway, the whole fair copy is perfectly legible.

At the beginning of the book I’ve placed a page of acknowledgments. Almost all of the poems contained in the manuscript have been either published or accepted for publication very soon. (For example, Mr. Ransom writes me that four of the poems in the fifth section—“Girls Walking into Shadows”—are going to appear in the Summer issue of the Kenyon Review.) I don’t yet have letters of permission from the editors of the various magazines and books in which the poems have appeared, but they are almost all of them people with whom I have friendly correspondence of one kind or another. I’m sure there would be no difficulty whatever in securing permission; so I felt free to include a page of copy in the manuscript, just to suggest what it would look like.

On the page which introduces section VI (“The Lean Ones”), I’ve written a passage, very brief, from René Char’s poem “The Rampart of Twigs.” A friendly correspondence with M. Char convinces me that

there would be no trouble getting his permission, and that of his publishers (Gallimard, Paris) to quote the line. It is rather an important epigraph for the section of poems: “Dear beings, whom the dawn seems to wash clean of their torments, whom it seems to restore with a new health and a new innocence, beings who will nevertheless shatter and vanish after a couple of hours … Dear beings, whose hands I can feel.”

The book is constructed in 6 sections. The whole book begins with a prayer to the Muse, and it is both a description of my farm life in Ohio and also an implication of that horrifying old Greek story about the lazy brother’s being the blessed one. It is a poem about being loved without deserving it. And the final poem in the whole book—“Saint Judas” —is both a dramatic monologue (though very short, a sonnet in fact) and a statement about the significance of a loving action (i.e., such an action can have moral meaning only if it is performed without hope of reward—and Judas, who was in the perfect position to perform an action without hope of reward, by his performance of hopeless and despairing love attains what I would hope to regard as sanctity). The book is designed to unfold its theme between these two brief poems: the theme of human love as a kind of miraculous agony. One does everything possible in order to escape it, and yet it is everything.

The first section is called “Lunar Changes.” It contains seven poems. Each of them deals with some sort of miraculous change, and all have to do with the love that this painful change embodies. Even the comparatively “light” poem about Andrew Marvell’s housekeeper—in addition to being a serious parody of Marvell’s style, which I admire and envy as much as any English style I know—places the speaker Marvell in a position (that of ghostly death) from which he cannot possibly hope to gain any reward for the poems which, after all, he wrote because he loved them. Incidentally, his housekeeper, Mary Palmer, actually claimed to be his widow after his death, and actually did publish his verses with an introduction signed “Mary Marvell.” She wanted to get some of the back rent money, or an equivalent. Think of it! To smirk at her would be blasphemous. Marvell—even Shakespeare himself—would have adored her. What better way to use Marvell’s beautiful poems in the world than by selling them in order to pay the back rent after his death—dunned by creditors and evading debtors’ prison? And so Marvell’s ghost loves her, even if they weren’t married after all

(he was very young, and I imagine she was a sour old hag—if so, so much the better). Each of the poems in the first section uses some device of transfiguration or other, and most often it is the moon, the sudden emergence of the moon, at once coldly impartial and warmly illuminating.

The second section is called “Midnight Sassafras.” The title of the section comes from the penultimate line of the first poem “Complaint,” an elegy for my grandmother. This poem, and those that follow it in the section, combines the theme of the defeated and the unrecognized with a further development of the theme of love, the love that I am trying to celebrate in this book—the highest love I can think of, which is given without reserve, whether the beloved “deserve” it or not. I might observe of the poem called “A Note Left in Jimmy Leonard’s Shack” that it is to be considered a note written by a little boy to the brother of the town drunk—fearful and disturbed at the possibility of the wicked old bastard’s drowning drunk in the river; and it is also an attempt to see if I could get away with making the kid hysterically call the frightening older brother a “son of a bitch” without making the reader snicker. American profanities are beautiful, but they have a diminishing effect, they cancel each other out. One curious result of this effect is that, in the Army, where everybody swears as a matter of course, it is almost impossible to create a genuinely original and felt curse; so that soldiers are always being driven, by the exhaustion of their own formal poetic diction, to the invention of new curses. Somebody must study this matter some day.

The third section is called “Fire.” The religious theme, I suppose I can call it, rises in this section. The desire for the love (as previously presented) is shocked by the evil and violence of nature, and by the fact that many of the miraculous transfigurations in the natural world seem to have nothing to do with man. I suppose the climax of this section is the last stanza of “At the Slackening of the Tide,” in which, after the beautiful and peaceful afternoon at the beach has suddenly been transformed into lamentation and hell by the drowning, the futile drowning, of the small child, the speaker in the poem looks to see if the waters will mourn for man, and hears only the sea itself, far away, innocently washing its hands of man, like Pilate.

The fourth section is called “Surrender.” It tries partially to answer the terrified question asked in section three: where does a man find his

place in a natural world where the significance of life—life itself—can quite possibly be transfigured into nothingness in a single unpremeditated moment? The answer given in section four is perhaps corny, but it is the only one I know of. The section consists of three love poems to my wife and—I was about to say “children,” but I must explain a strange detail. In dedicating the section, I mention “Marcella”; but my wife won’t have her second baby till July. If by some off chance you should find the manuscript acceptable, and if by some off chance my own anticipations should be frustrated and the baby should not be “Marcella,” then the manuscript would have to be changed. (Can you imagine any arrogance—the arrogance of a cocky young man—greater than that, more profoundly infuriating? It’s like commanding the grass to bloom.)

The fifth section is called “Girls Walking into Shadows.” All I can say is that these poems are all about the pitiful young. Since I am thirty years old now, I must sound like a prematurely old man, as I have no doubt I am, in some ways. The final poem in this fifth section, “On Minding One’s Own Business,” was completed very recently, and has just been accepted by Harper’s Magazine. It occurs to me that it summarized the whole theme of the section very well, so I placed it just yesterday at the very end. All the poems deal with the virtue of our letting one another alone. Thoreau, I guess.