1964–1966

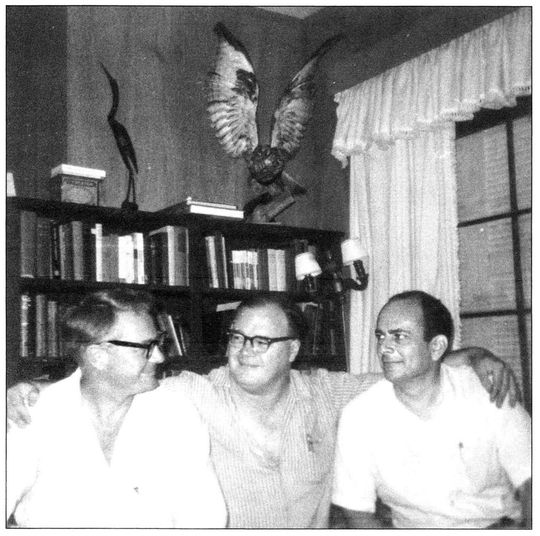

Robert Bly, James Wright, and Louis Simpson, Madison. Minnesota, circa 1964

I suddenly realized that I absolutely could not bear to live in the Twin Cities again. As you surely know, I care very deeply for Minnesota itself—its countryside, I mean; and I believe I am not exaggerating when I say that I love the Bly farm as truly and freely and fully as I love any place on earth. But Minneapolis is another matter. I have had so many failures there, failures of every kind imaginable, and so many wounds, and so many defeats, that I just came to realize that the city has become, to me, a city of horrors. If only I could find some other place to live, I think I could be well again.

—from a letter to Carol Bly

January 16, 1966

January 16, 1966

By 1962 James’s marriage to Liberty had ended in divorce. She and the two boys moved to San Francisco. In the spring of 1963 James arranged to take a leave of absence from the University of Minnesota to serve as guest professor at Macalester College in St. Paul for the following term. Before the spring semester was over, however, he was denied tenure at the University of Minnesota.

The only respite in James’s life was frequent visits to the Bly farm. The companionship, affection, and respect he received from both Carol and Robert gave him the strength and courage to survive the terrible experiences occurring in his personal life and created a lasting and important impact on his poetry.

“The farm is a beautiful, peaceful place,” he wrote to Donald Hall. In a letter to Robert he said, “I think your farm is the first such place I have ever really liked—it is beautifully mysterious and very much its own secret place.”

While teaching at Macalester, where he was devoted to his students, James moved to Saint Paul and lived in a series of rented rooms and small apartments. He worked extensively on both a new manuscript and The Rider on the White Horse, a translation of short stories by Theodor Storm, and carried on a voluminous correspondence with many people. James taught a second year at Macalester College, by which time he had received a Guggenheim Foundation Grant that would enable him to leave Minnesota after the spring term in 1965.

Before he left, James packed carton after carton of possessions: books, phonograph records, clothes, drafts of poems and translations, manuscript notes for courses, and letters. Thirty-four of these boxes were left at the Bly farm; half a dozen were stored with Bill Truesdale, a friend and colleague from Macalester; and others to one or more students.

Only the boxes cared for by Bly and Truesdale were recovered, which may help explain the absence of any letters from the year 1963.

After leaving Minnesota in the late spring of 1965, James spent several months in Cupertino, California, with Elizabeth and Henry Esterly. In the autumn he stayed at the Bly farm and then went to his parents’ home in New Concord, Ohio. He had planned to go to England, but a visit to his close friend Roger Hecht in New York City during the winter of 1966 convinced James that Manhattan might be a good place to live. He applied for a teaching position at various colleges in the area and was accepted by Hunter College.

St. Paul, Minnesota

March 4, 1964

March 4, 1964

My dear Franz,

Just now, it is almost midnight. Today the very air that we breathe in the twin cities is sagging heavily with a strange white snowfall. After I lectured three different classes today, and doing some other necessary work earlier this evening, I decided a little while to follow my custom of taking a solitary walk for a few blocks, to get a breath of fresh outdoors air, and generally to rest my eyes—and also rest my spirit—after the day’s labor. Then, as I walked down Dale Street from Selby Avenue here in Saint Paul, I suddenly found that the very innermost, most secret part of my mind had become filled with a soft clear light—the light that is like the green radiance of the air at that beautiful moment in Spring or early Summer when the shower of rain, that sprang up suddenly and fell down just as suddenly, is instantly gone, and left behind it a few people—like you and me, who like rain—soaked to the skin but happy to be soaked to the skin, and to be standing on a street corner, and feeling as though we ourselves were slowly turning bright green. How strange it was to catch myself, this evening, in the act of having a daydream of that kind, when all the while I slogged pleasantly through deep lakes of slush by curbs, or carefully picked my way across the six-inch snowfall on unfrequented sidewalks, balancing myself like a tightrope walker, in order to take advantage of the few big footprints left in the deep new snow by some gone and forgotten mailman, or milkman, or adventurous Great Dane—(of course, what I had secretly hoped to discover was the enormous footprint of somebody’s pet Elephant in the snow—but, I’m sorry to say, the last pet Elephant who lived in this neighborhood has moved away, to take a job writing books full of People-jokes).

But my most secret and most honest spirit, my dear Franz, was filled with light anyway, in spite of the snow. Because I walked into the fresh garden that still, and always, goes on growing deep in my mind, regardless of the troubles I face, the loneliness I feel, or the snowfalls I explore in search of some lost and mostly forgotten Elephant-prints. I walked into my garden; and you were there, waiting for me beside a dripping bright green house that grew right up out of the ground like a wild bush of flowers, a house with roots of its own; and you too were green and fresh, and you too were growing. You looked up patiently to greet me, and said, “Hello. You’re a little earlier than usual; but then, I suppose I’m early, too.”

“Well,” I answered, “I was just taking a walk outside in the snow, and suddenly I found myself wanting to come into the garden. I didn’t know why, until I saw the light shining there; and I knew that Spring had come; and I knew you’d felt so strong and hopeful this year that you’d started to grow already; and I knew that the garden in my most secret heart was shining with happiness because it is time for your birthday; and so I just came in to see you.”

“Thank you,” you said, and smiled a bit vaguely, as if there were some question that you wanted very much to ask but still hesitated, out of politeness, to mention.

But I already knew the question, and had answered it even before you thought of asking it, or wanted to ask it.

“I want to tell you something special, something that should be made clear, Franzie. You see, this visit with you in the garden was just a single, sudden inspiration that I had this evening. It is a very happy inspiration; but it is nevertheless just a message to wish you joy of the Spring, and to wish you the happiest of all happy birthdays!”

“Yes, I see,” you replied, still looking entirely puzzled.

“In plain English, my dearest friend and fine son whom I love completely and forever,” I answered, “in plain English, what I’m doing now is just greeting you with words. But the present which I am arranging to send you for your birthday this year—well, now, that’s a horse of a different color!”

“Are horses green this year, like houses and boys named Franz?” you asked, still not quite sure what I meant.

“Whether or not horses are green; whether or not my letters to you are too short and too rare; it remains a fact that, in addition to this

evening’s message—this letter to you—I am going to send you your present quite soon. It won’t be a letter, although I’ll write you a note about it. It will be a surprise, of course. Anyway, it will be a real, solid present which you’ll receive in a package through the mail. Happy birthday, once again! And always!”

“Happy birthday—always!—to you, too,” you answered, smiling. “Happy birthday, Daddy, no matter what the date of the year is, and in spite of the snow.”

“Thank you, my beloved son and best friend,” I replied with true love in my heart, “I know just what you mean. And now, if you’ll excuse me, I’ll just go back and get a night’s sleep; so that, tomorrow, I can go ahead with plans for your present. Good night, my dear.”

“Sweet dreams,” you said.

And I said, “Yes.”

Love, and more letters soon, I promise,

Dad

Dad

St. Paul

March 13, 1964

March 13, 1964

Dear President Rice:

My brief talk after dinner at the meeting of Kappa Delta Pi last Monday evening led me through a door, one of those two or three doors that somehow simply open for him at those moments in his life that are, somehow, eternal. Such a door opened in a green hillside at an odd moment when Jacob Boehme, the great 16th-century German theologian and mystic, was still a youthful cobbler’s apprentice taking a stroll through the countryside on his day off. Even before I received your magnificent letter, I had been filling my journal with wonderstruck ponderings on the strange, sudden beauty of last Monday evening. It was truly as though a door had suddenly been opened and for a moment (not a “mere” moment, but an eternal one) all of us seemed to step silently through the door and emerged into a green place, a meadow of renewal: all of us—the President and his lady, the members of the faculty, the students, and the evening’s speaker.

We all stood there together in the green place, and we held one another’s

hands. I discover in myself a response to your letter that is as profoundly authentic a response as I have ever felt, a response to something in your letter which reveals you as a man. It would have been gracious enough, heaven knows, had you simply greeted me; and, heaven also knows, I am old-fashioned enough to love the old formal civilities. But your letter, beautiful in its form and dignity, expressed not only the form but also—radiantly, indeed—the very meaning of what is, to me, most beautiful in Christian civilization. Edmund Burke has a great phrase for this meaning. He calls it “the unbought grace of life.”

My present note to you sounds somewhat awkward, as I read it over. I came to the meeting Monday evening feeling uncertain and lonesome. And yet, consider what happened! Suddenly I realized that I was living in a moment which included everything I ever cared about as a teacher, as a writer, and as a human being among my fellows; included, and surpassed. If my note sounds awkward, it does so because I have never been so moved for so many truly personal reasons as I am moved by your letter.

I would now like to say something which so far, as a new teacher at Macalester, I have hesitated to say. At the most recent faculty meeting, you mentioned to the faculty how barbarously certain students reacted to your explanation of the new cafeteria plan. You told us, with a dignity, a nobility which was a revelation to me of what a civilized leader truly is made of, you told us that, whatever the students might wish to do to Harvey Rice, you would not stand for their hissing the President of their college.

I want to say that I would not stand for their hissing Harvey Rice either. The beautiful graciousness of your letter to me displayed the same noble vitality which made your words to the faculty so admirable.

I trust you will forgive me for mentioning, even in passing, a problem which cannot help but be distressing in its complexity. But your words at the faculty meeting have haunted me for several days, and I trust that you will accept what I say here as a token of faith in you.

It made me happy to talk with Mrs. Rice also, and I hope you will convey to her my warmest friendship and gratitude, as well as my highest respect.

Sincerely,

James A. Wright

James A. Wright

St. Paul

March 13, 1964

March 13, 1964

My dear Sister Bernetta,

It is just about daybreak. After an entire night of work, and a dawning moment, I suddenly turned to write you a few words, in obedience to an impulse—no, it is a voice, not an “impulse”—from within.

The voice speaks very often, and it occurs to me just now that perhaps I need only try to follow the voice out of the many voices, the one that bids me stand and live.

Your pages from the European journal are very beautiful to read and ponder, as indeed I do again and again. I read them over and over during those long hours when—still unsuccessfully, I fear—I have been actually trying, trying, trying to do something which is strange to me: I have been trying to meditate. Oh, I have “killed time” before in my life, plenty of it; and I have loafed stupidly; and I have gazed in stupor at the waste, and heard nothing.

I have actually begun to learn at least the difference between the above modes of non-being and true meditation. I believe I can truly say that it is not identical with them.

I find a beautiful solace, a real joy, in speaking to you this way—answering you, almost.

As you well know, I will give each of the copies of The Branch my most loving attention; and, probably, send them to you just before Easter.

Bless you,

Jim

Jim

St. Paul

March 13, 1964

March 13, 1964

Dear Ed,

Thank you so very much for the check, which arrived today. May I begin this note by immediately mentioning one or two matters that you will need to know about the job which I’ve just finished?

(1) Miss (?) Ines Delgado de Torres wrote me a very kind note, dated March 3. (May I ask you, Ed, to convey to her my gratitude for her nice words of encouragement?) She was concerned about ten pages which were missing from the manuscript of The Rider on the White Horse, by which title I’m referring to the last of the eight stories; and by this time you should have received the missing pages. I had devoted an entire day, literally from daybreak to twilight, working and completing those ten concluding pages, lavishing upon them all my attention and imagination. It is very, very strange, almost unearthly, to realize what happened: after I had labored on that final scene with what can only be called ferocity, I laid them aside in an envelope; and I guess I just forgot about them, even when I put the entire manuscript together to send you. Now, here is what is so strange—I quote Thomas Mann’s account of Storm’s own obsessive concentration on those same final ten pages: “Storm lived almost to one-and-seventy. His ailment was the local affliction that plays a fateful part in one of his most powerful tales: … cancer of the stomach. He rose grandly to the occasion and demanded that the doctor be frank with him as man to man. But taken at his word, he collapsed and gave himself over to gloom. It was clear to those about him that he would not finish the White Horse, the finest and boldest thing he had ever ventured on. ‘Children, this won’t do,’ they said, and put their heads together to deceive the aged poet, who as an artist stood in a Tacitean-Germanic sera inventus, but as a man had overestimated his strength. His brother Emil, a physician, held a consultation with two colleagues; after which science pronounced that the verdict of cancer was all nonsense, the stomach ailment not malignant. Storm believed the tale at once. His spirits rebounded; he spent a capital summer, in the course of which he celebrated his seventieth birthday with the good Husumers in festive mirth. Also he brought the White Horse to a triumphant conclusion, thus elevating to a height never before reached his conception of the short story as the epic sister of the drama. I was bent on giving this little account as a conclusion to my tale (of Storm). The masterpiece with which Storm crowned his lifework was a product of merciful delusion. The capacity to let himself be deluded came to him out of the will to live and finish the extraordinary work of art.”

Ed, both in the concentrating and in the temporary forgetfulness, I seemed almost to have succeeded in summoning up the great shadow

of Storm himself, because I have loved him and his work for years, and needed his presence in the final stages of my work on him, as it were. After completing his story, he died; but I just forgot. I am not dead. (Believe me, Edgar, I am not.)

Miss Torres also noted that there was a poem in the story “A Green Leaf” that still needed translating. I am enclosing the translated poem with the present letter. PLEASE NOTE: the prose-translation of the poem should appear in italics in the printed version.

(2) After talking with you by phone and resuming work on my introduction, I unfortunately found that something more than occasional brief repairs were needed. Although I sincerely apologize for the additional slight delay, I am nevertheless certain, Edgar, that you would not want me to apologize for laboring to produce the best essay I was capable of, for all the time it required. In any case, the final revision of the introduction was mailed to you by airmail on Saturday, March 14, and by now you should have it. I myself feel about three times as secure about it as I felt about the previous and unsatisfactory version. I hope you like the new one all right, of course; but I want you to phone me (and leave a message, if I’m not there) in case there’s any further question about either the introduction or the manuscript of the translation itself. For your own convenience, let me say in writing, here and now, that any editorial corrections or revisions that you yourself might wish to make are perfectly all right with me. Even in addition to the devoted trust of old friendship, I am certain beyond question that I can utterly rely on your own sense of fitness in editorial matters generally; and, more particularly, you already know how deeply I believe in your own beautiful gift for hearing—as well as creating—the harmonies of prose.

I’ve added the point at the end of the previous paragraph simply to spare you further time and inconvenience if you feel that further revision—which you yourself can handle—is desirable. On the other hand, it goes without saying that I am willing to go on personally rewriting the introduction till hell freezes over, if you want me to.

Let’s see: I think I’ve covered all remaining practical problems.

Edgar, I am fairly bursting to continue this letter with several other considerations, at once personal and practical. For one thing, I feel dreadful in realizing what an absolutely indifferent and irresponsible slob your fellow editors must consider me, in view of the length of time I spent on the Storm translation. But it is not true! (I want to cry.)

While I was working on Storm, I had to deal with two or three matters that I honestly believe I can call catastrophic (and I am aware of the dangers of self-pity and exaggeration here). In fact, the chance to work on the Storm translation was, more than once, the chance to go on living, almost the one chance.

But we can talk about these things soon, Edgar. I want to thank you and the others for giving me the chance to work on this translation. Never once was it a burden. It was always, rather, a source of nourishment and refreshment; and the completion of the book is the fulfillment of an old dream of mine [ …]

It is Spring, and … the leaves are falling upward!

Love to you and your family,

Jim

Jim

St. Paul

March 16, 1964

March 16, 1964

Dear Miss Richer:

I’m sure you need never fear that “it is seven kinds of insolence” to write a letter as charming as the one you recently wrote to me. In fact, it is one of the kindest things you could do, particularly in a country like America, which becomes the more huge and the more lonely the more we love it. But even if it were as small as one of its own river towns, and even if we all hated it, to write a friendly note to a person who is an utter stranger to you except for some of the verses he has written—that is a lovely thing to do. Thank you.

But I’m afraid I don’t quite see how I can help very much with the poem called “Heritage.”66 I don’t mean to be huffy and aloof about it. On the contrary. And I don’t mean that I think it capable of providing a “total experience” (to quote your own excellent phrase) already, beyond the possibility of obscurity. Far from it. All I mean is simply that I don’t quite understand just what you are asking me to clarify.

I will tell you all I know. It is a poem about my grandfather. He was a terribly violent man who constantly held his wife and children at bay

by regularly frightening them witless through his indulgence in drunkenness so fantastic as seriously to call into question his capacity for any human feeling whatever. Moreover, he devoted his long life to the effort—apparently—to become the very opposite of what used to be called, in more gracious times, a “good provider.” For some reason, which relatives have never been able to fathom, he hated, really hated people who said things like “good provider.” He is not at all a victim of apathy For all his obsessive negations of things, he was not to be merely identified with the farmer’s horse in the old story. (The horse—as they said in Ohio—would sometimes amuse himself during the ploughing season by persistently straying off across the furrows to the edge of the field, where he butted his head against as many trees as he could manage before the farmer could catch him. One day a passing stranger called over to the farmer from the road, and asked what the hell use it was to try to plough with a blind horse. “Blind? Blind?” bellowed the horse’s owner, astounded. “That horse ain’t blind!” “Then why does he wander off from the line of furrows and bump into all them trees?” “Oh, that,” said the farmer; “well, you see, some days he just don’t give a damn.”) But my grandfather gave a damn. He went in the other direction, awesomely. And yet, he couldn’t be disposed of as a misanthrope. The mere mention of his dead brother Jim suddenly evoked from him such baffled and deeply affecting expressions of love that, at such moments, he puzzled his relatives far more completely than he did during his times of normal, predictable destructiveness.

When he was quite old, I was just a small kid. You can imagine how delighted he was at my name, and he told me so. I believe him. I love him, too.

He was struck down on a street in Bridgeport, Ohio, and died with his broken back inadequately tended to.

My family in Ohio have great powers of affection, but for some reason we are all unbelievably reserved with one another, not only in matters of feeling but even in matters of transmitting the plainest and most obvious bits of information. I didn’t know completely how my grandfather had lived and died until about three years ago, when my older brother—after such a long time, such an impossibly long, long, endlessly long time—told me the story and its details.

Now, Miss Richer, I don’t claim that this long-drawn-out explanation

will make the poem any clearer. And that it ought to be made clearer seems to me beyond question.

I hope you’ll forgive me for seeming to respond to your request for clarification with a letter which, in part at least, is less a helpful answer than a mere request for clarification of your request!

Again, thank you for your kindness in writing me. May I ask who you are? I would be delighted to know.

Sincerely,

James Wright

James Wright

St. Paul

April 2, 1964

April 2, 1964

Dear Kenneth,

I believe you’ll forgive me for such a long delay in replying to your splendid letter, which was dated February 24. The reason for the delay is a perfect revelation of the kind of idiotic inefficiency which possesses my mind almost in direct proportion to my desire to be helpful to a friend. In short, instead of following your simple directions and just writing down four or five names on the postcard which you enclosed. (For heaven’s sake! Think of it! You did everything except phone me long-distance and then arrange for an answering-service to hold the line while you flew here to St. Paul by jet-plane to speak my answers into the phone, while I stood by grinning like an amiably maddening imbecile—a kind of civilian Good Soldier Schweik.)

[ …] I sincerely hope that I’m not too late to be of some help to you, however small. I will proceed this evening to do two things: first, I’ll complete this letter to you; second, I’ll type out the names of young poets whom I mention in the letter, and send you both the postcard and the letter—I feel that the latter might serve as a kind of explanation of the names on the list—and also, of course, an occasion to greet you and wish you well.

First, the names of the poets under thirty-five whose work I know well enough to declare without hesitation that I really like it—whose poems move me in the same way, and for the same causes, that, say, the poems of a very great poet like Tu Fu move me. In other words, I want

my selection of names to be guided by a spirit which moved you to write (in your prefatory note to the One Hundred Poems from the Chinese, which includes the thirty translations from Tu Fu, and which I can honestly describe as one of the most personally precious books that I have) something like this: “I make no claim for this book as a piece of oriental scholarship, by the way. Just some poems.” Discovering your Tu Fu translations was like rising from the dead, as far as I’m concerned. And so, in the same way that they might be called “just some poems,” I hereby offer some names of young persons who are “just some poets.”

1. The first who comes to mind with full force, and seems to me an unmistakably beautiful, deeply fertile, unaffected, marvelous poet, is a young man of about 25 years of age who has the wonderfully unpoetick name of Bill Knott [ …] His work has appeared in the latest issue of Choice, the Chicago magazine edited by John Logan. (It’s the issue that contained Robert Bly’s scarifying essay, “The Destructive Tradition in American Poetry”) Knott’s poems appear under the pseudonym of “Saint Geraud” [ …] If by chance you haven’t seen the issue of Choice mentioned here, I’m sure Logan would be delighted to get a copy to you almost immediately, so you can read the fairly substantial group of Knott’s poems published there.

2. Another young man, also about 25 years old, is named Tim Reynolds. He has had several poems published in Poetry (Chicago). I’ve never met him; but I’ve wanted for some time to write him a note of gratitude for the several beautiful, genuine poems that he has so far published in Poetry and one or two other places. I’ll write him this very evening—just a note of thanks for his poems, and a brief request that he send a few of his poems (say, 5 or 10, but no more) directly to you. I trust you won’t mind, or think me discourteous—I do realize that the task you’ve undertaken might easily threaten to snow you under with manuscripts from well-meaning but inefficient friends like myself. Still, I do admire the poems of Tim Reynolds; I believe you would like them, too, whether or not you have space to say much, or anything, about them in your projected essay.

3. Finally, a very, very quiet young man (a victim of one horrible streak of old-fashioned hard-luck after another … but never mind that, at the moment): a fellow named Dick Shaw. He is about 30 years old. He has been teaching, off and on, in Minneapolis for about

5 years. He holds neither the Ph.D. in Incomparative Cunnilinguistics (excuse the heavy-handed humor—I seem to be speaking in tongues this evening) nor a Teaching Certificate in Elementary Larkspur Lotion Selling-and-Distribution. He is just a quiet fellow who has been writing quiet and genuine poems, of real delicacy and unobtrusive strength, for the past few years. He’s published a fair number, and I wouldn’t mind seeing a selection of them in a book. Anyway, I think he is a good poet, and I would like to see him get some help. Even a word of encouragement can have enormous meaning for such a man, as you well know. Of course, the worth of his poetry is something conceivably quite distinct from his need for encouragement. (We all need it, for heaven’s sake, even when we write bad poems—perhaps especially then.) [ …]

There they are:

1. Bill Knott

2. Tim Reynolds

3. Dick Shaw

Thank you, Kenneth, for asking me to help. It is a true honor to be asked to help, however slightly, in a project conceived by one of the most generous and civilized men I have ever met. If I can be of any further help, I hope you will give me the chance to do so.

I was in New York City last week, where I spoke at the new Guggenheim Museum, and fooled around with a publisher for whom I’ve just translated eight Novellen from the German of Theodor Storm, etc. I hear that, to my regret, I had just barely missed seeing you again. Anyway, I did get a copy of Natural Numbers, which simply delights me—it contains almost all of the short poems of yours which I love best, and which still seem to me a new beginning, our true life.

Best,

as always,

Jim Wright

as always,

Jim Wright

St. Paul

April 8, 1964

April 8, 1964

Dear Arnold,

I am certain that I speak only with the restraint and gravity suitable to the occasion, when I tell you that your beautiful letter to me (dated 23 March) was incomparably the most important achievement I have ever made in my life as a man who loves the high literary art. I want somehow to assure you, Arnold, that I am fully aware of the honor which you’ve done me in inviting me to contribute a critical essay to the volume of studies on Roethke’s poetry. The more I ponder your determination to “honor Roethke not by testimonials of praise” but rather by our best and truest efforts to see his work “in the hard, Sophoclean light” exactly as the young Pound asked to be seen, I am astonished at the splendor and nobility of your conception. For implicit in a gesture which ignores even a moment’s possibility of flattery and promptly begins the essential labor of criticism—that true criticism which is so rare among men, and so instantly recognizable for its magnificent terror of confounding its tentatively outlined summaries of poems for the “secular sacrament” (in Mr. Ransom’s dark and oracular phrase) that is moving and serene at once, and at once the ending and the beginning of the word when it is comely of vesture and countenance and then suddenly awesome in the bluntness of its unarguable deathlessness—implicit in the quiet, grave gesture toward seeing Roethke’s poetry in the company of Landor and Donne and Ben Jonson is in itself, I do most reverently believe, the gesture which Roethke labored and fought for a lifetime to make. To cherish his work, his art, by demanding that it respond to our most severe and attentive questionings by revealing suddenly, as it were, the precious stones that vein it, and accordingly by daring it to sag or crumble or heave up geologic “flaws” or more crumbling sandstone and fool’s gold, is to love the art as the poet himself loved it. I believe that, as time passes, and as factions perish and seas move and all the rest that dies and dies forever is forgotten, some of Roethke’s poems will remain among all our priceless things. And it is only the true criticism, the honorable effort of our very best intellectual attention, that can clarify for us what there is of immortal and mountainously enduring in Roethke’s art. I think of those cranky, somehow haunting lines of Mr. Winters: “Few men will

come to this: / The poet’s only bliss / Is in cold certitude, / Laurel, archaic …” Arnold, I’ve written a bit more than a mere grateful acceptance of your invitation would require, because I wanted to clarify for myself the deep meanings which I instantly sensed in your distinction between mere rote praise and the living praise of critical devotion; and I feel, even more deeply now than at the beginning of my letter, how very beautiful and noble your plan is. In addition to considerations which I’ve been so far touching upon lightly and unsystematically, there are perspectives and kinships and echoes that become clearer with each moment: there is the very great tradition of aristocratic friendship and the sense of loving duty, of Vergilian pietas that is its very inmost vital spirit, the love that tenderly asks the friend to please us by acting and living and working in aspiration toward the achievement of the high style, the deed that Sidney would instantly notice and know as precious, and the work of art in words, the evidence that the friend pleases us in studying to sing whatever is well-made. In such an eternity of friendship, such a garden of worthiness, perhaps Ben Jonson’s phrase about Shakespeare’s impatience with revision reveals how shallow its apparent curtness truly is, and how deep is its tenderness and affection; perhaps Jonson meant simply that he would not have his friend live, even forever, in any work in any sense inferior to his highest ability: the occasional work of classical achievement, the poem that does not really need our flattery, that in fact grandly ignores the chattering supererogatory bleatings and fawnings of the trivial and silly false critics who apparently live with the miraculously idiotic [ …] that to praise what is itself nobly worthy of praise is a facile act that any fool and knave can lightly toss off, as they themselves were no doubt tossed off quite as lightly, and then got “twixt asleep and wake.”

Oh, Arnold, I am deeply moved by the beauty of the plan you’ve asked me to help you to fulfill. I accept the invitation with all the pride I am capable of; and I pledge you my best powers of thought and feeling as I slowly seek to write truly and honestly of Roethke’s work. I’ll be in touch with you to ask your advice from time to time as the essay takes shape.

At this moment I know myself able to respond to what is noble, to recognize the true radiance when it appears at last, and to love my friends and masters because they are themselves the very embodiments of the nobility which they invite me to share in my best faith. I want to

quote some lines which leaped this instant to the very center of my mind’s stage out of their accustomed shadow in the wings from which for years they have whispered me counsel about words; I want to quote them because they are to my mind great and noble, certainly the kind of high poetry that Roethke aspired to be worthy of:

It is not growing like a tree,

In bulk, doth make man better be:

Or standing long an oak, three hundred year,

To lie at last a log, dry, bald, and sere.

A lily of a day

Is fairer far in May;

Although it flower and die that night,

It was the plant and flower of light.

In small proportions we just beauties see,

And in short measure life may perfect be.

In bulk, doth make man better be:

Or standing long an oak, three hundred year,

To lie at last a log, dry, bald, and sere.

A lily of a day

Is fairer far in May;

Although it flower and die that night,

It was the plant and flower of light.

In small proportions we just beauties see,

And in short measure life may perfect be.

“The greatest of all desire,” Nietzsche remarked, “is the desire to be great.” You and I have both many times heard Roethke quote with resonant and ferocious approval those lines in which Yeats asks (as his words seem carved on marble in the very air before our eyes) for himself, and for all true poets touched by the fire-coal in holy secret, to be praised or damned by his peers and in the presence of their own nobility:

I know what wages beauty gives,

How hard a life her servant lives,

Yet praise the winters gone:

There is not a fool can call me friend,

And I may dine at journey’s end

With Landor and with Donne.

How hard a life her servant lives,

Yet praise the winters gone:

There is not a fool can call me friend,

And I may dine at journey’s end

With Landor and with Donne.

An inn for the high-hearted pilgrim, indeed! To fancy Roethke sitting down at table for supper is a fine dream. Joy to that sparse company or the rare ones who are both blessed and can forever bless.

As always,

James A. Wright

James A. Wright

St. Paul

April 14, 1964

April 14, 1964

Dear Kenneth,

On April 2, I wrote a reply to your request for the names of a few young American poets whose work I enjoy and who might help you in your essay on American poets under 35. I’m sorry to be so long in securing a few poems by Dick Shaw, one of the three persons I mentioned and discussed. You see, I was invited to spend a couple of days last week at a Catholic girls’ school named the College of St. Scholastica, up at Duluth—I spent the time well, I think, in strolling and chatting with the nuns or the girls in the classes, or with both, and also in lecturing on such matters as what I feel is the “underground” connection between such seemingly diverse Americans as E. A. Robinson and Whitman (a stream of agony and sympathy for bums and sixteen-year-old soldiers and all the others who, in the period of American manifest destiny, were getting pushed in front of sadistic surgeons or pre-Edward-Teller weapons, or else were getting shoved down manholes and behind roadside billboards), and the really very thrilling fact that Robinson was aware of himself as the end of something and of Whitman as the beginning; and I talked about Irish street-poetry of the 18th century; and also about the art of translation and its joys (I quoted your remark explaining why you give time to translating the great poets of Chinese and other languages: “You meet such a nice class of people”); and I generally kept busy with those rather fine, touching girls up there in Duluth.

Then I returned and got copies of five of Dick Shaw’s poems from his sister-in-law, who’d secured and typed them in the meantime; and I hereby enclose them.

Again, please let me know if I can help any further.

Yours,

James Wright

James Wright

St. Paul

April 27, 1964

April 27, 1964

My dearest Marsh,

A few days ago, I received a letter from Momma. She told me that Franzie had received his birthday present all right, just as I sent it to him through the mail. But she told me that the record which I had sent to you through the mail … had arrived but, when you unwrapped it, it was broken!

I imagine some accident happened that nobody was really to be blamed for: maybe some nice, friendly pet Elephant was sitting in a post office one evening, feeling in need of some friendly conversation or perhaps a bit of excitement and games, to while away the time until the Postman-in-Charge-of-Elephants-Being-Sent-Across-America-By-Parcel-Post got him all wrapped up and put enough Postage Stamps on him to take by First-Class-Mail from Chicago to, maybe Mukilteo, Washington, or perhaps to Cucamonga, Southern California. Maybe that nice pet Elephant was just sitting all alone in the Chicago Post Of fice Parcel-Room and happened to look down and find that his cagedoor had somehow come unfastened. Well, if I were a pet Elephant, and if I had a chance to sneak out of my cage for a few minutes of recreation before resuming my Postal Journey, and I snuck out and started snuffling and nuzzling around the other Packages, and if one of those packages happened to smell (or taste) like a record of The Story of Sinbad the Sailor, well … I don’t think I could resist unrolling my elephant’s trunk and just flipping the Record up on the turntable of Record Player, just to hear a teeny bit of The Story of Sinbad … Wouldn’t you do the same thing, Marsh?

And so the record must have slipped and broken.

I believe you and I can understand how such things happen, my dear big boy Marshall.

So I patiently waited for the chance to get to a department store and find you another record.

I am happy to be able to tell you what I found: another, brand-new copy of exactly the same record: Sinbad the Sailor! I also found a nice little book called The Friendly Tiger. I’ve sent you another little package containing the record and also (just to keep an eye on the record so

that it doesn’t get broken in the mail like the other one) the little book with the friendly tiger in it.

Love,

Dad

Dad

St. Paul

May 11, 1964

May 11, 1964

Dear Dorothy and Louis,

Several months ago, out at the Blys’ farm, I read Robert’s copy of At the End of the Open Road pretty nearly to a frazzle. I even have some of it by heart. Heaven knows how many letters of gratitude I wrote to you about it—only in my head, alas. But never mind (as night keeps whispering at the window). Resuming correspondence (and, in a very real sense, sanity, I think) at last, I’ll try to describe the weird dumbness and paralysis of will and heart that lay on me like a black cloud for month after month after month during the past year. But that, as I say, is for later newsiness.

The occasion of the present moment is the only occasion when the past is worth a damn anyway; and the past has got to work its way into the present through proper channels. Take this present moment. Earlier today I had a note from my former wife, in the course of which she mentioned her own pleasure in the Pulitzer Prize for this year.

It is about time.

My own pleasure in the award, Louis, is rather more complicated than Lib’s (though by no means any less sincere, for all that). I mean that I have what I would confidently describe as an unusually thorough experience of your work; for I have read The Arrivistes, and copied many of its verses into a little notebook of my own; and I’ve read, many times over, Good News of Death; and also A Dream of Governors. Now, I have pondered the poems in these four volumes. Several of them I have got by heart. I have a good sense of what they sound like, because I have read them aloud for my own secret sake, over and over, as a composer of serious intelligence will sometimes withdraw to some private place and play Mozart over and over—not, as some might think, for the sake of the instruction alone, but first of all for the joy of

the music. Anything a man learns that doesn’t come to him permanently by way of the joy that it gives him is, well, just not much worth learning—I suppose one might learn, from sitting on stoves, not to sit on matches; or learn, from listening to LBJ, for Chrystes sake, not to sit on radios or pull the ears of television tubes; or learn, from vanity, to learn the duty of misery; or … but never mind, never mind. The prize makes me happy, because the poems make me happy, for themselves and also for their tremendously original fulfillment of the earlier fulfillments in the other books. What I mean is that The Open Road is certainly not to be understood as the only fulfillment, the only finished achievement, among the four books … it’s not Louis Simpson Makes Good By DISPENSING WITH IAMBIC VERSE (ah, me! you tell him, Louis, you try him for a while: there isn’t enough strict iambic verse in the English language to bother resisting; anyway, Wyatt already resisted it, and everybody knows that Wyatt was nothing but a passing dago, a mere hyphenated Guinea, a kind of nightingale-among-the-Assistant Professors, as one might say; so never mind, Robert, NEVER MIND!) … No, The Open Road is a new and wholly distinct work, one of whose most powerfully moving features is the unmistakable life that flows from one end of the whole book to the other and back again, as though the single poems in it, like the organs of a man’s body, are severally distinct and miraculously whole creations and, at the same time, the very fuels and engines of one another, as the ventricles can function alone only because the brain somehow remembers to imagine them alive and so grant them the shape of their own natural flowings and fallings. The book is overpoweringly one poem. One reads it—one is compelled to read it, all of it—from beginning to end, even if he merely thinks he is looking up a single poem for reference or renewed pleasure (I actually found this strange thing happening to me three different times, at the very least; I started out by trying to flip through the pages of The Open Road to find a single poem or line, and was almost irresistibly drawn to the beginning of the entire book, from which I simply found what I sought by reading my way toward it; and I loitered with it for a time; and then moved naturally and truly forward to the San Francisco lines and the end.) It is different in many other ways, also—different from the other books, a new shape of the book that has strangely loomed up almost of its own strength; it no more supersedes the great lyrics like “A Woman Too Well Remembered,”

say, or “The True Weather for Women,” or “Carentan,” or several others, than—oh, … than Africa can be said to “supersede” Asia or North America. Political regimes, stylistic fashions in poetry, be damned to them, we been there before; but a new continent uplifted from the sea only ennobles the Asias and Americas whose own forms are both new and old, and they return the nobility as the sea gave it. Nobody “owns” a true nobility, for God’s sake. In the presence of the noble, he is ennobled.

I feel ennobled by At the End of the Open Road. (And I mean it: any obscurities in this letter are the consequences of clumsiness in my effort to write down on paper the thoughts and feelings about a body of work which I suddenly have realized to be deeply important to whatever is vital and growing in my own character.)

Please give Annie and Tony my fondest love, and please accept it, with all gratitude, from

Your friend,

Jim

Jim

St. Paul

May 28, 1964

May 28, 1964

Dear Lib,

It’s just past daybreak. A few minutes ago, starting to type a clean copy of a recent manuscript, I rather absent-mindedly recorded today’s date in the upper lefthand corner, as I customarily do. Suddenly, within space of an instant, more than a decade of life vanished, and I recalled myself standing awkwardly in the presence of a weary, impatient, and yet amused police-clerk down on the other side of the Stiftskaserne in Vienna, which was (you’ll remember) all the way around the corner and far down the street from Breitegasse 7/11. The police-clerk sagged behind his ancient, worn-out desk, and the amazingly brilliant autumn sunlight seemed to sag with him, till he finally took on the appearance of a tree from which the very last leaf had given up the ghost and fallen to earth very very slowly, just in time to avoid the unfamiliar company of the very first flakes of snow. Do you remember? Surely you do; for I had to come and fetch you, in order to complete

the process of registration (Anmeldung). In my own memory I stand there forever, as eternal and golden as the sunlight of that happy time: a poor, God-forsaken American horse’s ass, incapable of remembering a crucially important date.

It was the date which I entered on my manuscript just a few minutes ago. Suddenly I felt the perfectly simple and spontaneous desire to write you: Happy birthday. I trust you not to be offended, for I meant no irony in writing that I hope you feel happy today. I realize that a decade of life isn’t to be wiped out of existence, just like that. On the other hand, I so seldom experience any simple, direct feeling of any kind whatever, that I just thought I would follow it for its own sake. And now that I’ve started, I think I’ll try to describe what’s happened to me during the past year, and where I seem to stand at the moment. But first I want to thank you for the good will, the friendliness, which you offered me in your letter of a few weeks ago. I don’t have it handy at the moment, I’m sorry to say. But I’m not going to let myself use that fact as an excuse not to finish this present note to you and send it. Instead of succumbing to such a paralysis of will (a truly horrifying experience, which I don’t know how to begin to describe), I’ll just mention one thing that I recall from your letter. You said something to the effect that you hoped I wouldn’t decline any offer of a job on the west coast simply because you were there. No, I wouldn’t decline any such offer for any such reason, Lib. But I’ve had no such offer. And next year I’m returning to teach at Macalester.

Let me say a word about Macalester. I began this past school year feeling as thoroughly defeated as I can imagine. The way I was treated at the university was utterly shocking. I will not at this time try to list all the details; but if you knew them—as I finally learned them only within the past couple of months—I believe you would clearly agree that they are offensive far beyond any personal failure of mine that might account for them. But to return to my earlier point about Macalester: I began classes last September with the conviction that everything in life, that I’d ever considered worth living for, was ruined almost beyond repair. Most terrible of all, my self-confidence as a schoolteacher was utterly shattered. As I vividly recall that time a year ago, only one connection with reality was left: that was Edgar Doctorow’s miraculously heartening assurance that my big book of translation from German—the Theodor Storm stories—which I’d been

totally unable to work on during the terrifying months of insanity in the spring (I’m not kidding: insanity), could still be completed and that the publisher would certainly accept it. I had nothing else to turn to; and I turned to that book again. I often wrote for two or three days over a weekend, indifferent to food and sleep, simply because the only alternative that occurred to me was literal death. Bit by bit I clutched a way back to the everyday world. When classes at Macalester actually started, I had regained enough hope to at least want to face the wreckage of reality, and to start to rebuild myself as a teacher, rebuild literally from scratch. Day after day after hellish day, I labored more intensely than I’ve done on scholarship since I studied Latin in high school. And day by day revealed no particular progress, no particular sign that my effort had any meaning; I just struggled blindly on. There’s a place in E. A. Robinson that suggests how I felt for months: where he speaks of “some poor devil on a battlefield / Left undiscovered, and without the strength / To drag a maggot from his clotted mouth.”

Then a startling thing happened. It was last March 13th. The student-officers of the Macalester Students’ Honorary Society requested that I deliver an after-dinner speech at their monthly meeting. I consented, and prepared a lecture on “The Art of Translation.” I arrived at the meeting totally surprised to find it a very formal, serious gathering, attended by every dignitary at Macalester, including the President and his wife. Be that as it may, I delivered my lecture, and went home. In a day or so I received an astounding, magnificent letter from President Rice. Moreover, he had caused copies of his letter of praise to be sent to the Dean of Students and to the Chairman of the English Department (Ray Livingston, of course). Actually, what had happened wasn’t particularly spectacular: I had just been heard and judged as a teacher and scholar by someone who wasn’t a hired spy or a company fink or a vicious fool. Anyway, I was indirectly asked how I would like to be invited to Macalester again. I said I would accept with relief.

At this point, I must introduce another element in the course of events, a very strange one which still strikes me as silly, at best, and perhaps even a bit unreal, a bit irrelevant to me and the way my life appears to be shaped. It turned out that Mrs. Elizabeth Kray (from the Poetry Center of the YMHA in New York, formerly, and now an official

at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum—you met her once in Minneapolis, and she liked you a great deal) had been exploring the possibilities of my being granted a fellowship by the more famous branch of the same family: the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation. The entire affair is weird, ironic: I was sent application forms three times in personal notes from the chief director of that huge Foundation, and simply (so help me God, I speak the truth) simply forgot to answer his notes, much less fill out the forms. My private feeling then—and, to a large extent, even now—may be described as a plain refusal to believe that such things as fellowships, grants, etc. (that is, the very idea of an entire year of opportunity to work on my next book without at the same time being forced every moment to struggle with suffering and punishment and anxiety of an endless, hopeless kind) had anything to do with me. Now, let me return for a moment to the letter from the President of Macalester (mentioned in the previous paragraph): I clearly informed the Macalester authorities that, however ironic it sounded, a Guggenheim fellowship was being all but shoved down my throat; that I was unable to take it seriously enough even to reject it, in the improbable event that it might be offered me; and that, regardless of the Guggenheim’s decision about me, I definitely was willing to return to Macalester next year. Then, if the Guggenheim was granted me, I would postpone it until at least the Autumn of 1965; and, if such postponement were not allowed, then I would simply reject it. Well, more briefly, I officially was offered the Guggenheim fellowship. I was also officially invited to return to Macalester next year. I intend to return, because they are short of faculty and need me; and also because I need them. I honestly can’t imagine any other way of regaining the minimum of health, psychological health, absolutely necessary to go on living. As for the Guggenheim, it was at least a month-and-a-half ago that I received the official letter granting me the fellowship. I haven’t even written a note of acknowledgement, though I’ve received two urgent special-delivery requests for such a note. Within the next couple of days, I’ll try to write a request for postponement; but it will be pretty half-hearted. The plain truth is that I still don’t much care to get emotionally entangled in what is sure to be an impossibility. My conviction is that hopeful things don’t happen to me, and so to hell with them.

Incidentally, Robert Bly received a Guggenheim; he accepted it

immediately, and combined it with some other award he’d just received. He and Carol and their two little girls (the younger is named Biddy; she is as bald as Yul Brynner, a nice baby) left their farm about a month ago. The last I heard, they were headed for the town of Thaxted in England, near London, to visit Donald and Kirby Hall; but I don’t know what they plan thereafter: somewhere in Scandinavia, I imagine.

Oh, yes, Lib, I just recalled another item of news in your letter: about Louis Simpson and the Pulitzer Prize. I was pleased, and wrote him a note of congratulation. He has written well for many years, and he deserves the recognition. Do you ever see him and Dorothy? They’re in Berkeley again. The address I have for them is 800 Spruce St., Berkeley 7, Calif. Dorothy always liked you, and you liked her too. You should call them … Right now, I’m exhausted, and I begin summer school soon.

Love to you & the boys (I’ll write them soon.)

Jim

Jim

St. Paul

May 29, 1964

May 29, 1964

Dear Louis,

I must say how delighted I am to have your letter. You sound marvelous, clear-headed and confident in your own decisions about the nature and depth of your strength. There was always an amazing toughness of independence in your work; and the more you come to accept it for what it is (simply the normal breathing rhythm of a man who is, in Keats’s startlingly irreducible phrase, “among the poets”), the more fully you seem able to give clear expression to your very great resources of personal kindness and generosity … I seem to be getting lost in rhetoric already. Let me try again, because I think the point is important … One of the most characteristic of your poems (I think it’s in A Dream of Governors) is a short one in which a man wakes at night, recalls some moment of his previous life as a combat soldier, hears a night-breeze blowing through the window and over himself

and his sleeping wife and children, and just lies there awake and smiles to himself; and then comes the last line-and-a-half of the poem:67

… His life is all he has,

And that is given to the guards to keep.

And that is given to the guards to keep.

The phrase “His life is all he has” trembles in every single word, every single letter, every pause even; and I choose the word “trembles” with some care; for I want to suggest how your phrase (indeed, the whole poem) suddenly and conclusively discovers a poetry of tenderness, and discovers it in the very act of creating a poetry which is true—to yourself in the present moment, and consequently to your personal past, and, again consequently, to our whole American history that truly does reveal itself when we wake at night and allow ourselves to feel that strange, strange tenderness toward our own lives and all other lives that are awake or asleep at that very moment; for the tenderness is somehow the very resource of strength that clears the mind and makes it attentive to our own nature in this country. Maybe I can describe what I mean a little more clearly still, by quoting an odd remark which I recently found in José Ortega y Gasset’s book History as a System (now in a Norton paperback, and very worthwhile, by the way): “Man has no nature; he has only a history …”

It occurs to me that your power (practically unique just now) of evoking such splendid and dark poetry from the stream of American history is perhaps the simple consequence of your personal admission (again, just about unique) that such a thing as American history actually exists.

I don’t mean to imply any scorn for the American writers, historians and others, who don’t seem to realize, or admit, that our history exists. It takes some courage to admit that. And sometimes the moments of that history are so comic that they can make a person shiver with something like fright. For example, I read somewhere (I think it was in Frederick Lewis Allen’s Only Yesterday) that a few enterprising newspapermen, apparently as cynical as the disillusioned reporters at the beginning of the chapter in Miss Lonelyhearts called “Miss Lonelyhearts

and the Clean Old Man,” took a trip to Marion, Ohio, to interview the father of President W G. Harding, before the Teapot Dome affair was publicly revealed. Now, these reporters asked old father Harding just how in hell the President could be so stupid as not to know that his bosom-friends of the Ohio Gang in Washington were ransacking the public till and laughing behind his back. Harding’s father, according to Frederick Lewis Allen, meditatively continued chewing his plug of tobacco for a few moments, and then remarked,”Well, all I got to say is, it’s a damn’ good thang Warren warn’t born a wawman. He’d always be in the family-way. Just can’t say no.”

I just thought of a recent “Peanuts” comic-strip which I found, and which in a way embodies something of the same sense of frightening assininity (sp?) that President Harding seems to suggest. I’ll enclose the “Peanuts,” but please return it to me after you’ve shown it to Dorothy. Charlie Brown is simultaneously heartbreaking and infuriating.

I can’t say how grateful I am for the comments you made about the poems which I sent you. The comments provided just the right tone that I very much needed: without jumping into the poems blindly and blindly trampling underfoot both the weeds and the potential flowers alike, you stood patiently among them and thought about your own feelings, and then told me what you thought. I am so clearly in agreement with nearly everything you’ve said, that I’m writing the present letter during late afternoon, a kind of crest of a wave of revision and further writing which your intelligent, considerate comments helped to release.

However, let me remind you of a very important qualification of which you’re already aware: please do not feel that I will be disgruntled, or resentful, or bitter,—or anything that would oppress you with guilt, however minor—if you should ever receive a batch of new poems from me and find yourself just too out-of-sorts, or too distracted, to comment on them specifically. It goes without saying that your comments are enormously welcome and helpful; but they are all the more helpful for having come freely and spontaneously. In exactly the same spirit, I am eager to receive your own new poems—the ones which you mentioned in your wonderful letter. I propose the following principle: let’s both feel entirely free to send each other some poems; let’s grant each other the widest possible latitude of criticism and comment—all the way from the kind of very careful and specific comment which

your recent letter offered me, to a mere acknowledgment by one of us that he’s received verses from the other. Do you agree? I make this suggestion because I believe it will provide the best atmosphere, the freedom to read a poem and merely say that you like it or don’t like it. After all, we read things that leave us cold, and we don’t know why, nor do we care; on the other hand, we read some things (Thomas Hardy wrote some of them) that Randall Jarrell, for example, could go on picking apart avidly in hell through all eternity, and yet we are entirely willing to just let Hardy write his own poem in his own way, because we know it is beautiful and noble and well-made, we don’t really care how.

Agreed? I very much hope so. I am, as I say, really eager to see your new poems. I will respond to them, I know; and I’ll write down my response as truly and clearly as I possibly can.

As a token of my enthusiasm, I enclose a couple other new pieces. My God, I feel something of what a grizzly-bear must feel a few minutes after he wakens from his hibernation.

I have a letter from Robert. It was written from England, just across the street from Donald and Kirby Hall in Thaxted, about 40 miles from London. The mere thought of Robert in England is odd, isn’t it? But not really: the oddness is an illusion planted in my mind by Robert’s performance of a role. It can be an entertaining and even useful role, nevertheless: I heard him tell the assembled English Departments of Carleton College and the Morris, Minn. branch of the U. of Minnesota that, compared with poetry in some other languages, “English poetry can scarcely be said to exist.” Nonsense, yet it pleases me sometimes to think of it. (Louis, I sincerely hope you will find it in your heart to forgive me for the previous sentence. Sometimes I fall into ghastly bad taste.) Robert’s letter begins characteristically: “Well, here I am in England! I feel like a whore in a police station! Etc.”

By the way, speaking of people who have trouble respecting the English, I’ve just read all the way through the Collected Poems of Hugh MacDiarmid. He is a great poet. Sometimes he is sublime. I’m not exaggerating. Robert once told me you’d met MacDiarmid. I hope so. I wonder about him. It occurs to me that his poems often embody the

same powers of independent courage and tenderness that I mentioned at the beginning of this letter.

This letter is long enough for this time. Before I conclude, however, I want to copy out some riddles which I’ve recently collected into a little notebook. I think that your little girl Annie might like them. As for me, I think that #1. (in the list below) is one of the most wonderful things I have ever encountered in the English language:

RIDDLES FOR ANNIE SIMPSON

1. What’s purple, weighs about two million pounds, and lives at the bottom of the sea? (Answer: Moby Plum.)

2. What’s black and yellow, and squeals when you turn it over? (Answer: A school-bus.)

3. What’s black and lives in a tree and is very dangerous? (Answer: A crow with a submachinegun.)

4. What is covered with salt and has a twisted mind? (Answer: A thinking pretzel.)

5. What is soft and yellow and lethal? (Answer: A shark-infested custard.)

6. What’s brown and has two humps and lives at the North Pole? (Answer: A lost camel.)

7. What’s red and squishy and comes through the wall? (Answer: Casper, the friendly tomato.)

Love to all,

Jim

Jim

St. Paul

June 6, 1964

June 6, 1964

Dear Jack,

I’ve been up all night writing like hell (it’s now—Jesus Christ!—it’s now exactly 1:37 p.m.!) And I suppose I’m just hysterical enough—or perhaps outright drunk on words—to have one of my rare flashes of insight: viz., everytime I admonish myself to actually answer your incredibly beautiful and devoted letters to me, I start to punish myself with a separate guilt for each letter; and, since the letters number into

the hundreds, I always end up throttled once again with guilt. However, just a moment ago I realized that I was by this time so God damned guilty that I had become almost innocent again. So I figured I’d just give up the “plan” to answer your letters one at a time, and simply write to you.

Please be patient again, Jack old man: I’m going to mail this note right now, so that I won’t be able to leave it half-finished for the next five years. It will be step number one. Number two will be a copy of my latest book (which Roger Hecht assigned its prize-winning parodytitle in the regular competition among old Kenyon wags: viz., The Branch Bank That I Broke Last Year, and Other Revels). It isn’t really very much of a book, but I hope it pleases you some.

What is gray, weighs six tons, and sings calypso? (Answer: Harry Elephante.)

(I believe that one is the chief masterpiece in this major new genre.)

I’ll be in touch sooner than you can possibly think. You write too. Meanwhile, here goes this little letter, for once!

Love,

Jim

Jim

St. Paul

June 6, 1964

June 6, 1964

Dear Dick,

Your letter is such an important moment in my life on this earth, that I have finally come to realize why I haven’t been able (literally, I haven’t been able) to answer it. For how could one “answer” one of those passages in which a good man’s utterly selfless generosity and lovingkindness suddenly, by authentic miracle, become perfectly identical, body and soul, with the words in which he offers the entire abundance of his spiritual life to another person? Are you acquainted with James Dickey? In a thousand astonishing, unexpected, and yet inevitable ways, he and I have become the most deeply steadfast and enduring of friends; whenever we meet, either by accident or design, we invariably devote at least a couple of hours of our visit to a slow stroll somewhere—last Spring he spent a whole weekend at Macalester, and he

and I picked our way down the steep eastern bank of the Mississippi and then walked on and on and on, now and then tossing a sanddollar out over the slick, melting ice—Jim flung one so perfectly sharp and ferocious that it skipped clear out past the very frailest lace of dissolving ice and skated on and on and on, over the dark blue water itself, clean out to the middle of that wide river, almost—and, as always, we communed in silence a good deal of the time. He is a manly, tender, affectionate person of great physical strength, utter courage, pride, dignity—in one of his poems he speaks of his brother’s “loved face,” a phrase that would have occurred only to a genuinely strong man. He is also, in my opinion, a critic of almost frightening lucidity, depth, and force—I think he is the most intellectually brilliant literary mind of my generation. And his own poetry continues to move, volume after volume, toward the fulfillment of his unique radiance of imagination. (In a poem about one of his solo-combat-flights in the Pacific during the Second War, he writes of suddenly feeling someone peering over his shoulder, and turning instinctively and catching a glimpse of “a great ragged angel of sunlight.” The radiance of the phrase is entirely characteristic of his great poetic gift) …

Well, during such strolls during visits together, Jim and I do occasionally speak aloud, mostly about the few poets and poems that are secret and indispensably precious to us both. I can distinctly remember at least three different occasions, including the stroll down to the Mississippi last Spring, when Jim Dickey and I quoted the poetry of Richard Eberhart to each other aloud, and then proceeded with the stroll in silence, so that we could listen to the echoes.

Your letter to me was a presence, as your poems have been for a long, long time—indeed, ever since I was an undergraduate at Kenyon College (1948–1952) and learned of your poetry through your (characteristic) generosity in giving a new poem of yours to the editor of our old literary magazine Hika. Ever since then, I have cared about your poems as I care about few others. More than that: I’ve studied them, fiercely, and tried to learn something of the inner craft of them (the greatest of them invariably convey an unmistakable sense of your own astonished and astonishing discovery of each poem’s holy secret, its unrepeatable and eternal miraculousness) …

And so, when I finally—finally!—was blessed and honored by meeting you in New York, I had that strange feeling of confirmed

faith, that comes to us a few times—I felt, truly, like a devoted friend of yours already; and now I earnestly hope that the friendship is formally sealed by the good clasping of hands.

I said (above) that I couldn’t properly speaking “answer” your beautiful letter; and just before I began to write to you, something else that is precious to me came leaping like unannounced lightning into my mind. Without pretending to explain why, I feel that it’s important to copy it out for you; it made me happy to remember it, and I hope it pleases you, too. It’s simply a few scattered sentences from Thomas Hardy’s gorgeous novel The Woodlanders. The parts I suddenly recalled with such overwhelming clarity a moment ago are concerned with Hardy’s mysterious, green, unutterably beautiful character named Giles Winterbourne, the young man who lives and breathes in the intimate presence of the trees (mostly apple trees) which he raises in his own woodland tree-nursery, and who, each autumn, suddenly is transformed into Autumn itself, as he travels about with two horses and his home-made cider-press.

Here is Hardy’s little account of Giles’s appearance in the latter role, as he is seen by the girl Grace Melbury, at the very moment just after she has finished speaking with Fitzpiers the tree surgeon, now vanished. Grace stands musing about her pet horse:—

“Thus she had beheld the pet animal purchased for her own use, in pure love of her, by one who had always been true, impressed to convey her husband away from her to the side of a new-found idol. While she was musing on the vicissitudes of horses and wives, she discerned shapes moving up the valley towards her, quite near at hand, though till now hidden by the hedges. Surely they were Giles Winterbourne, with his two horses and cider-apparatus, conducted by Robert Creedle. Up, upward they crept, a stray beam of the sun alighting every now and then like a star on the blades of the pomace-shovels, which had been converted to steel mirrors by the action of the malic acid. She opened the gate when he came close, and the panting horses rested as they achieved the ascent … (Giles) looked and smelt like Autumn’s very brother, his face being sunburnt to wheat-color, his eyes blue as corn-flowers, his boots and leggings dyed with fruit-stains, his hands clammy with the sweet juice of apples, his hat sprinkled with pips, and everywhere about him that atmosphere of cider which at its first return each season has such an indescribable fascination for those

who have been born and bred among the orchards. Her heart rose from its late sadness like a released spring …”68

(Yet another passage, just a plain, simple, sort of homely description, and yet it is a miracle that must have occurred to Hardy’s imagination as helplessly and overwhelmingly as a blossom occurs to a branch. It deals with one of Giles’s visits to the town of Sherton Abbas, where he regularly takes orders from the townsfolk for saplings grown in his nursery. The apparition of good, green Giles Winterbourne from the country, standing confused on a town street-corner with his arm around an apple-tree that he’s carrying along with him, must have made Hardy simply close his eyes in a moment of prayer, just before he recorded this vision):—

“It was his (Giles’s) custom during the planting season to carry a specimen apple-tree to market with him as an advertisement of what he dealt in. This had been tied across the gig; and as it would be left behind in the town, it would cause no inconvenience to Miss Grace Melbury coming home.

“He drove away, the twigs nodding with each step of the horse69 … (Next, the girl Marty South, who sometimes helps Giles in his nursery and who is also visiting town on the same day, catches sight of him, again and again, during her shopping):

“It was impossible to avoid rediscovering Winterbourne every time she passed that way, for standing, as he always did at this season of the year, with his specimen apple-tree in the midst, the boughs rose above the heads of the crowd, and brought a delightful suggestion of orchards among the crowded buildings there. When her eye fell upon him for the last time, he was standing somewhat apart, holding the tree like an ensign, and looking on the ground instead of pushing his produce as he ought to have been doing. He was, in fact, not a very successful seller either of his trees or of his cider, his habit of speaking his mind, when he spoke at all, militating against this branch of his business.” (And, finally, Giles’s keeping his appointment with Grace Melbury):—“His

face became gloomy at her necessity for stepping into the road, and more still at the little look of embarrassment which appeared on hers at having to perform the meeting with him under an apple-tree ten feet high in the middle of the market-place … He gave away the tree to a bystander as soon as he could find one who would accept the gift …”70

Your letter was like the tree, I think, and I was the bystander; I accept the gift, indeed, with great happiness and gratitude. (I feel delighted endlessly by Hardy’s words; may they refresh your spirit also!)

Yours,

Jim Wright

Jim Wright

St. Paul

June 8, 1964

June 8, 1964

Dear Oscar,

Your letter of June 3 sketches a stunning vision of the New Anthology of the Great Poems in the English Language.

I am honored and delighted by your invitation to contribute a brief critical note (1000–1,500 words) to this book, which may very possibly be your anthologistic masterpiece. (I mean what I say, and with my whole heart, Oscar; everybody who cares about poetry surely carries in his secret heart a spiritual anthology without which he could not live and breathe at all; and I would say, conservatively, that fully half of the poems I love best were poems that you revealed to me, magician that you are.)

Of the three poems which you offer for my critical note, may I work on Frost’s “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening”? I am instantly confident that I can write you something succinct, sound, and worthy.71

You will understand that I merely offer the following information to you as a loving suggestion, which of course you will use or ignore, entirely as you see best: Among the three poems which you offered for my critical contribution to your new anthology, you included Yeats’s “A Dialogue of Self and Soul.” I love this great masterpiece, but learning is required as well as love, in order to do it justice; moreover, it requires a scholarly gloss; and such a gloss must, I realize, be a model of sensitive taste and brevity. All these points lead me to inform you that my friend and former colleague, Dr. Sarah Youngblood, Dept. of English, Univ. of Minn., is on the threshold of publishing a Handbook on Yeats. Oscar, I would stake my mind, my feelings, and indeed my very life on the promise of her handbook’s power and importance. It will be instantly recognized, by anyone with half a brain, as one of the curiously few necessary introductions to Yeats. Sarah is a genius. If I were Yeats, I would wobble her ouija-board. In short, she could do the masterful note on the Yeats poem. I’ll mail this note now. More soon.

Jim

St. Paul

July 6, 1964

July 6, 1964

Dear Mr. Tranströmer:

I want to beg your pardon for seeming so ungracious and ungrateful in my long silence. More than four long months have passed since my friend the poet Robert Bly traveled from his farm in western Minnesota in order to visit me in St. Paul; and, of course, he brought with him, among other things not nearly so pleasing, your beautiful letter to me. May I assure you that, in spite of appearances to the contrary (in view of my long delay in replying), I was immediately and deeply grateful to you for your letter? In fact, I have read it over many times; and was prevented from promptly answering—prevented by a tangle of problems too obscure and, perhaps, too dull to describe at this time.

I suppose the best proof of my good faith in demonstrating my gratitude is the enclosed group of new poems. When I call them