On the morning of 13 August 1704, an Allied army of around 52,000 men under John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough, met a slightly larger Franco-Bavarian force led by Camille, Duc d’Hostun – more commonly referred to by his secondary title as the Comte de Tallard – near the Bavarian town of Höchstädt. The previous year, a French army under Marshal Villars had crushed an Imperial army on this same ground and now, Tallard found himself unexpectedly in a position where he was unable to refuse battle, the result being a disaster for French arms that saw him a prisoner of war and his army in tatters. In the English-speaking world, the battle was named after Blindheim, the small village which saw the fiercest fighting and where the largest concentration of French troops was encircled and captured, and by its anglicized form – Blenheim – it is the name most synonymous with Marlborough’s career.

In his recent account of the battle, the historian Charles Spencer refers to Blenheim as having ‘stopped the French conquest of Europe’, and yet whilst the 1704 campaign shows Marlborough at his best, not only as the possessor of a strategic sense that places him head and shoulders above his contemporaries but also as a battlefield commander of the highest ability, the battle did not stop the French military colossus dead in its tracks nor did it – as has also been argued – shatter the myth of French invincibility. This myth took a severe drubbing during the Italian campaign of 1701 when Prince Eugène of Savoy first overwhelmed a French force at Carpi in July and comprehensibly defeated a numerically superior Franco-Savoyard army under Villeroi at Chiari in September, before capturing this self-same officer at Cremona five months later.

Throughout his final illness, King Carlos II of Spain was pressed by the various contending factions to alter his will in favour of their nominees. Under pressure from the Church, he bequeathed his kingdom to Philippe of Anjou, grandson of King Louis XIV, in the mistaken belief that all parties would accept his decision and the Spanish monarchy would remain intact. (Author’s collection)

The main effect of Blenheim was to remove, once and for all, the Bourbon threat to Vienna with the inherent possibility that, by thus knocking Austria-Hungary out of the war, France could militarily enforce the last will and testament of King Carlos II of Spain.

The king was a product of generations of extreme inbreeding, which had resulted in his developing a series of severe mental and physical disabilities. Both of his marriages had remained childless and, in an attempt to stave off the horrors of a disputed succession, his advisers needed to find an acceptable compromise heir outside the direct line of succession, as the two principal candidates – his cousins, King Louis XIV of France and the Holy Roman Emperor, Leopold – were the focal points of the Bourbon–Habsburg enmity that had divided Europe for the better part of the 17th century.

Naturally neither party could countenance the enrichment of his rival to his own detriment and, anxious to avoid another war, Louis began to open secret negotiations with the Maritime powers, England and the United Dutch Provinces, Austria’s most prominent allies and two nations who already had their eyes on the expansion of their overseas trade at Spain’s expense. After lengthy negotiation, it was agreed that the principal heir would be neither Louis nor Leopold, but Leopold’s six-year-old grandson, Josef Ferdinand of Bavaria, whose claim was drawn through Maria-Antonia, the Emperor’s only child with his late wife, Margaret Theresa, an elder sister of Carlos II, through his father’s second marriage.

To sweeten the pill, it was agreed that the Bavarian prince would receive metropolitan Spain and the overseas colonies whilst the contentious parts of the European inheritance would be ceded to the nominees of Vienna and Versailles – the Spanish Netherlands would go to the Archduke Charles (Leopold’s younger son through his second marriage) whilst the Italian territories – with the exclusion of the strategically important Duchy of Milan – would go to Louis’s eldest son, and namesake, the Dauphin. Milan would be granted to the Duke of Lorraine, who would in turn cede his possessions of Lorraine and Bar to the Dauphin. On paper the treaty guaranteed European peace, but foundered jointly on Austrian demands that Milan should also go to the Archduke and the fact that Carlos would not countenance the dismemberment of the Spanish monarchy; he would instead acknowledge Josef Ferdinand as Prince of the Asturias, his sole heir.

Spain was torn between pro-French and pro-Austrian factions but nonetheless negotiations between France and the Maritime Powers continued, with an agreement being reached that would see Josef Ferdinand becoming King of Spain, with the Archduke Charles receiving the Duchy of Milan and the remaining Italian territories going to the Dauphin. Again, it looked as if an agreement had been brokered but, on 3 February 1699, whilst in Brussels to receive the support of the Flemish nobility, the six-year-old prince took ill and died. The succession would now be decided between the Habsburg and Bourbon candidates and, in the final year of his life, Carlos, in an attempt to secure the integrity of the Spanish Inheritance, nominated Louis’s second grandson, Philippe of Anjou, as his sole heir, with the Archduke Charles being relegated to the position of third heir after Philippe’s younger brother, Charles of Berry.

Still very much an evolutionary form of the more common 18th-century weapon, this French bayonet dating from the early 1700s fits over the muzzle and is affixed to the weapon by a lug, through the socket at the base of the weapon. Unlike later developments, which place the blade to the side of the muzzle, this curved blade fits around the muzzle and is effectively a direct extension of the musket itself. (Copyright and courtesy of Royal Armouries, Leeds)

For Louis XIV, the legacy was a poisoned chalice which presented him with two options, neither of which were particularly palatable to him: he could accept the will and repudiate the treaty, thus antagonizing Austria and the Maritime Powers, or he could remain bound by it, which would cause both an unnecessary break with Spain and an inevitable break with Vienna. Reasoning that further conflict with the Habsburgs was well-nigh unavoidable and would thus certainly bring the English and the Dutch into the ranks of his enemies, the French king decided to accept the will, proclaiming his grandson to be King Philip V of Spain by announcing: ‘His birth called him to this crown. The Spanish People have willed it and demanded it of me: it was the command of heaven, and I have granted it with joy.’

Even now, war was not truly unavoidable. In London, the Tory administration was prepared to accept Louis’s assurances that the French and Spanish crowns would never be united, and in any event was prepared to ignore the Partition Treaty on the grounds that it had been negotiated by King William III without reference either to his ministers or to Parliament.

War, however, did break out when Austria sent an army under Eugène into northern Italy with the intention of seizing the Duchy of Milan and presenting both France and her allies with a fait accompli. Naturally, Louis sent troops into the Duchy of Milan, ostensibly to safeguard the Spanish possessions, whilst still continuing to negotiate with the Maritime Powers. Initially Austria fought alone; however, escalation was inevitable as, upon the death of King James II, Louis openly acknowledged his son, James Francis Edward, as de jure King of England in opposition to both the English Act of Settlement (June 1701) and his own undertaking, in the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick to recognize William III as King of England. In consequence this brought Georg-Ludwig, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg – whose mother, the Dowager Duchess Sophia, was by virtue of the Act now third in succession to the throne of England – into opposition with France, whilst elsewhere in Germany, the Elector of Brandenburg was negotiating with Vienna over the possibility of his support during the current conflict, his price being the elevation of his Prussian possessions to the status of a ‘kingdom’. This is not to say that the German states unilaterally supported the Holy Roman Emperor – the Electors of Bavaria and Liège–Cologne were members of the House of Wittelsbach, whose rivalry with the Habsburgs went back centuries and they saw an affinity with France as being the best way to gain ascendancy within the Empire, legitimizing their actions was the fact that Max II Emanuel of Bavaria was also Governor of the Spanish Netherlands and was thus obliged to uphold the late king’s will; in addition, in order to destabilize the Empire, France agreed to support and subsidize any future Wittelsbach attempts to secure the Imperial throne. A number of other, smaller, German principalities also tended to support the succession of Philippe of Anjou, but these were ringed by Habsburg supporters and thus neutralized.

‘The Pyrenees are no more!’ Aware that acceptance of the Spanish Legacy would lead to almost certain warfare but conscious that its refusal would almost certainly lead to a lesser conflict with the bullish Habsburgs, Louis allowed his grandson to accept the Spanish Crown with the proviso that France and Spain would never be united under a single monarch. (Author’s collection)

‘The Dynast’. Given that his second son would not – in theory – inherit the Imperial title, the Emperor Leopold constantly pressed the lesser claim of the Archduke Charles to the Spanish throne. The Habsburg designs on northern Italy, and Leopold’s refusal to compromise on what he held to be his son’s rights, would effectively plunge Europe into 13 years of unnecessary warfare. (Author’s collection)

In May 1702, a joint declaration of war was issued upon France by England, the Holy Roman Empire and the United Dutch Provinces, which brought both the Maritime Powers and the body of the Imperial states into the war in support of Austria, a move which prompted the Wittelsbach brothers to declare openly for France. Accordingly, the Earl of Marlborough travelled to the Low Countries where he was appointed Deputy Captain-General of the Dutch forces, and became de facto commander-in-chief of the Allied Army.

After a failed attempt to bring the French Army of Flanders to battle at Zonhoven on 2 August, Marlborough began to concentrate on taking the enemy-held fortresses along the Meuse in order to protect the Dutch hinterland. On 22 September Venlo fell and, with Liège capitulating almost exactly a month later, Marlborough was now well placed to garrison the fortresses of Kaiserswerth, Roermond and Stevensweert, effectively driving a wedge between the enemy forces in Flanders and those on the Rhine.

In the other theatres, the Allies enjoyed mixed fortunes. Whilst the fighting in Italy remained inconclusive, the advantage gained by the capture of Landau by Ludwig of Baden on 2 September was negated by the Bavarian entry into the war on the side of France and, when Ludwig withdrew across the Rhine, he was narrowly defeated by the French at Friedlingen on 14 October. Elsewhere, an amphibious attack on the Spanish port of Cadiz was beaten off, although honour was somewhat restored when the English admiral, Sir George Rooke, destroyed the Spanish treasure fleet at the battle of Vigo Bay. In 1703, Marlborough successfully captured Bonn on 15 May, placing more pressure on the Franco-Bavarians, but was tantalizingly unable to capture the port of Antwerp at the mouth of the Scheldt, but the initiative passed to the enemy when Villars and Max Emanuel crushed an Imperial army under Styrum at Höchstädt on 30 September. The scale of the French victory was to show that it was not only Marlborough who had to deal with the delicacies of coalition warfare, for when Villars proposed that the Imperialists should be immediately pursued back to the gates of Vienna, a dispute with the Bavarian Elector ended with the marshal resigning his command and being replaced by the more pliable Marshal Marsin. The year ended on a military high but a political low for France with further victories over the Imperialists on the Rhine and Max Emanuel occupying the Tyrol in order to secure Bavaria’s southern borders, whilst both Portugal and Savoy changed their allegiances and joined the Grand Alliance.

The French plan for 1704 was to detach a force of 70,000 men to upper Germany and from there to drive upon Vienna, thus knocking Austria out of the war and – despite much political rhetoric – enforce a settlement which would secure the Spanish throne for Philippe of Anjou. Versailles, however, had not reckoned with Marlborough’s strategic insight and, with a combination of detailed planning and disinformation in the face of the very real threat to the Imperial capital, he led some 20,000 Allied troops southwards from the town of Bedburg, in order to unite with the armies of both Ludwig of Baden and Eugène, who had temporarily left the Italian front, before turning upon the Franco-Bavarian forces before they could attack the Habsburg capital.

The march to the Danube was a masterpiece of strategic planning in which Marlborough oversaw every aspect of the route, from the choosing of encampments to the establishment of forward magazines. It was a campaign of feint and counter-feint that left his opponents unsure of both his intent and destination, sowing the seeds of indecision that would allow him to unite successfully with the other Allied contingents. Having combined his forces with those of Baden, who was campaigning in Germany, the principal objective was to secure a bridgehead on the Danube which would not only serve as a base of operations and logistical hub, but would also facilitate the juncture with Eugène’s forces coming up from the south-east, the final plan being that Eugène would screen Tallard’s forces whilst Marlborough and Baden would engage the forces of Marsin and Max Emanuel.

The town selected for Marlborough’s purpose was Donauwörth, where the bridge was overlooked by a fortified eminence, the Schellenberg, and as soon as the Franco-Bavarians became aware of the Allied plans, there followed a race to see who could occupy the town first, a race that the Allies lost, arriving before the town on 2 July. With the defences undergoing repairs and with the ramparts lined with enemy troops, Marlborough chose to forgo formal siege operations and elected to take the position by storm. Marlborough’s first two assaults were bloodily repulsed by the enemy garrison, but a successful attack by Baden on a section of the fortifications that had by now been denuded of defenders was the precursor of a third assault that swept all before it. Although the Franco-Bavarian force had lost heavily (5,000 casualties with a further 3,000 or so taken prisoner) the Allied returns told their own story: out of some 22,000 men deployed for the attack, over 5,000 – including ten generals and 28 colonels, killed at the head of their men – became casualties, a level of attrition unprecedented in the conflict to date.

‘The Master of all he surveys’. This 19th-century engraving of King Louis XIV of France manages to convey the monarch’s hauteur but, despite this, he was more than willing to make a compromise settlement over the Spanish inheritance. (Author’s collection)

‘The Engineer’. Vauban’s vision of a defensive grid, the pré carré, was to define the process of siege warfare for over four decades and would dictate the nature of the fighting in Flanders, much to Marlborough’s despair and frustration. (Author’s collection)

For the next month, the Allies devastated the Bavarian countryside in what was known as the ‘rape of Bavaria’ in an unsuccessful attempt to draw the Elector away from his loyalty to France, a process that was counterproductive as it placed undue stress on their own extended lines of supply and, as July turned to August, the two armies met to the north of Höchstädt in the battle that would bring Louis XIV’s aims for 1704 to naught and lay the foundations of Marlborough’s reputation as one of Britain’s finest soldiers. With the battle won, and the threat to Vienna thus averted, the Duke began to lay his plans for the coming campaign season and as the army began to retrace its route northwards, he took steps to consolidate the Allied position in the Moselle Valley by capturing Trier and Trarbach, where he established magazines for the next year’s campaign, with a third being set up at Koblenz, at the confluence of the Rhine and Moselle.

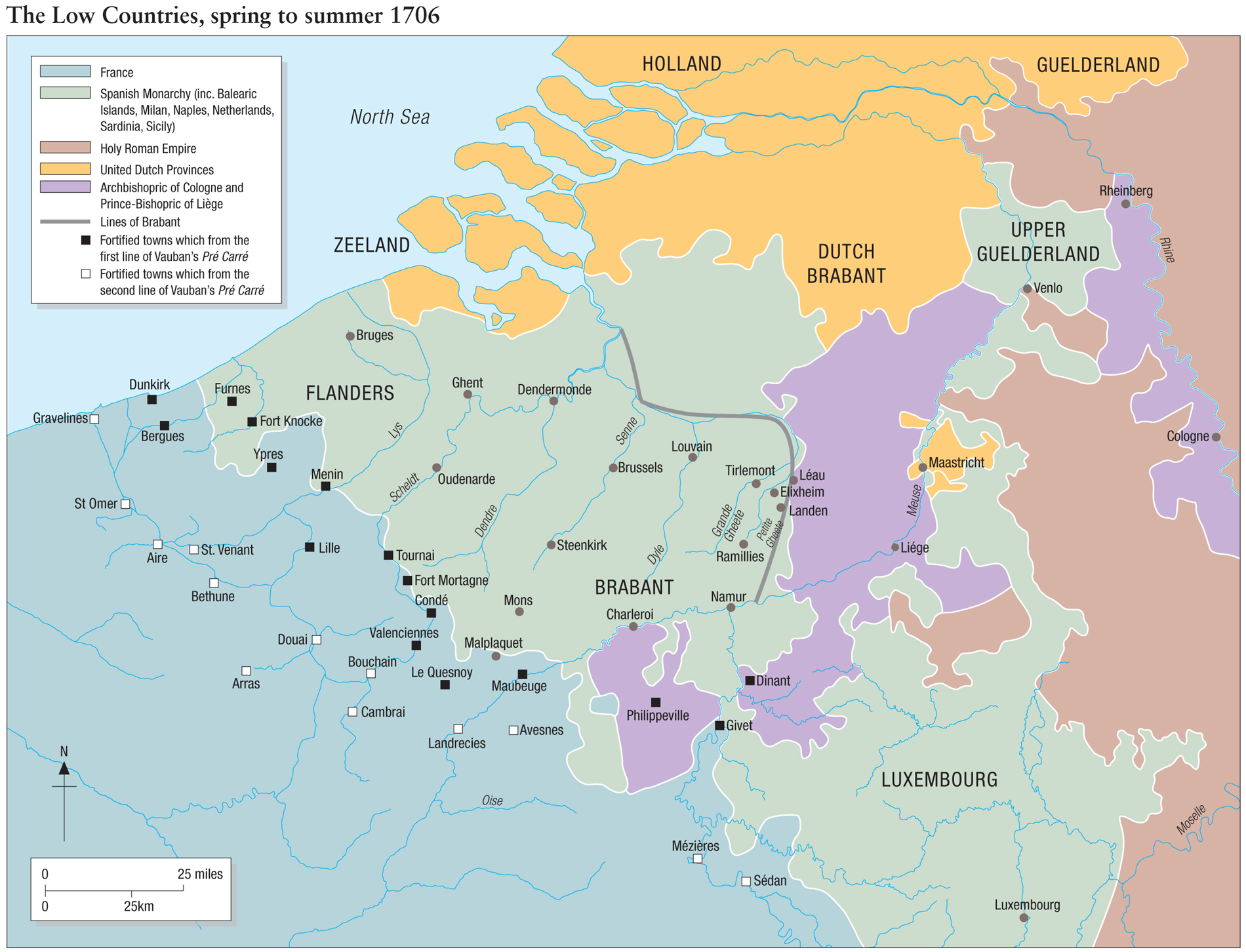

From the moment of his arrival in Flanders, Marlborough had been beset by the problems of coalition warfare – not only did he have to contend with the differing personalities of the military commanders, but he also had to reconcile his strategic planning with the various allies’ own diplomatic agendas; thus in the wake of the most comprehensive Allied victory of the war, he was about to propose a plan that would clearly be anathema to one important member of the coalition and simultaneously place an impossible strain on another. His plan for 1705 was intended to take the main theatre of operations away from Flanders, where strategic planning was constrained by the chains of fortresses, and instead launch an attack through Lorraine along what he called le vrai chemain – the true road. To modern readers, Marlborough’s proposed attack will be reminiscent of the plans for the German attack on France in 1940, to render her defensive fortifications obsolete by bypassing them.

Late 19th-century German postcard showing detail of the uniform and equipment of a trooper in the Bavarian Cuirassier Regiment ‘Arco’. (Author’s collection)

Boasting such fortified towns as Metz, Thionville and Verdun, the route was by no means undefended, and Marlborough’s plan relied on three interlinked premises: firstly, that an Imperial army of 30,000 men under Ludwig of Baden would advance westwards from the fortress of Landau towards the river Saar, supporting his own army of 60,000 men marching from Trier; secondly, that the Dutch forces under Ouwerkerk would successfully contain the French Army of Flanders under Villeroi; and thirdly, that France and her allies would not be able to recoup fully the losses that they had suffered at Blenheim, the Schellenberg and their aftermath; therefore Louis and his generals would be faced with the alternative of diverting manpower to suitably garrison the fortresses lining his route or of deploying sufficient forces in the field to meet the Allies in open battle. He was confident of the likely outcome in either eventuality and when Vienna expressed concerns that the plan would lay Austria open to an attack by Marsin from Alsace, he simply pointed out that an Allied advance would either draw the French marshal westwards, or force him into dispersing his forces to cover several positions at once. In any event he would be unable to take offensive action.

The Allies’ preparations throughout the winter had by no means gone unnoticed at Versailles and, as circumstance would have it, Louis was able to send perhaps the most talented of his commanders, the newly created Marshal Villars, who had been elevated after his victory at Friedlingen, to Lorraine, to take over the French forces there and organize its defence. This he did with vigour, and soon he was preparing a pre-emptive strike on the Allied magazine at Trier – which faltered because of adverse weather conditions – as well as a number of nuisance raids towards the Imperial camp at Landau. Believing that Marlborough would soon be attacking with almost 100,000 men, he decided that the best option would be to fortify a defensive position and invite attack. The French King was also politically receptive to the differences between the members of the enemy coalition and whilst he sent his finest general to take command of the threatened sector, he sent many of his best regiments, including Le Maison du Roi – his own household troops – to reinforce not only the Army of Flanders, but also the Dutch belief that the Spanish Netherlands would see France’s main military effort in 1705.

Despite Marlborough’s meticulous planning, the campaign was a disaster. Marching south from Maastricht, a number of Allied contingents had failed to join him and as a result he reached the area of operations with less than half of the number intended; next – and up on his arrival at Trier – he discovered that the magazines were less than half full; and finally the promised Imperial army failed to materialize. Couriers from Flanders brought messages of alarm from the Dutch Government, which naturally feared a French offensive, and the Duke sought to reassure the States General by promising that the success of his own campaign would force the enemy to return to the defensive in the north whilst they reacted to the threat from Lorraine. Fearing that a great opportunity would be lost if he abandoned his plan of operations, Marlborough elected to continue as planned.

This contemporary print rather overplays Marlborough’s ‘breaking’ of the Lines of Brabant during the summer of 1705. The works themselves were in no way as substantial as they are depicted here and the fighting was more in the nature of a heavy raid than a pitched battle. (Courtesy and copyright of la Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

A comrade-in-arms since their service together in the 1670s, Villars had a healthy respect for his opponent and took up a defensive position at Sierck, from where he would be able to cover the fortresses of Luxembourg, Saarlouis and Thionville, and where he could comfortably await reinforcement from Marsin in Alsace, which would increase his army to over 50,000 men. Believing reports that Marlborough’s army was still larger than his own, Villars surrendered the initiative to his opponent, who daily looked eastwards for the reinforcement that would allow him to take the offensive, and gradually his command was swelled by the arrival of troops from Denmark, Prussia and the Palatinate but of the Imperial troops under Baden, there was still no sign.

With time and supplies both running out, and with Villars seemingly content to remain on the defensive and outwait his opponent, came the news that Marlborough wanted least of all – Villeroi had attacked Huy and the Dutch were now demanding that he immediately detach 30 battalions from his army to reinforce Ouwerkerk and forestall any French successes in Flanders. It was, naturally, the end of Marlborough’s campaign. On 11 June, he wrote to Eugène, adamantly stating that the fault lay with the non-arrival of the Imperial reinforcements as – with those additional men – he would have been able to conduct offensive operations in Lorraine and, had he done so, the enemy would have been compelled to draw off troops from Flanders and thereby assuage Dutch concerns. Sickened by his allies’ actions, he resolved to lead the army until the end of the campaigning season and then lay down his command in favour of a more suitable candidate.

Victorian painting by Granville Baker showing the Duke of Marlborough leading the British cavalry against French infantry on the outskirts of Ramillies. Regrettably, in extolling Britain’s military hero, the artist ignores the contribution of her allies. (Author’s collection)

The collapse of his planned campaign should have come as no surprise to Marlborough as, since having assumed command of the Allied forces in the Low Countries, he had seen ample evidence of the conflicting war aims of England’s coalition partners. For the Dutch States General, the primary theatre of operations naturally remained Flanders and the Spanish Netherlands, the closest enemy concentration to their own borders, whilst for the Imperial princes, the main concern was focused on the Rhine frontier, whereas for the Austrian Habsburgs, their Imperial commitments notwithstanding, the only theatre of relevance, indeed the raison d’être for the war, was Northern Italy and the need to prevent it from falling into French hands. Priorities aside, then came the style of warfare: the Dutch preferred a slow and steady process consolidating their position through the prosecution of sieges and a gradual erosion of Vauban’s defensive system. On the Rhine the situation was complicated by the personality of Ludwig of Baden, the Imperial commander whose ego was seemingly greater than his desire for an Allied victory, whilst Eugène, the Austrian commander in Italy, remained closest to Marlborough’s temperament and own strategic vision.

Although constructed to a standard pattern, differences in this pair of English flintlock muskets illustrate the weakness of the contract system for procurement. As the century progressed, methods of manufacture would become standardized, culminating in the Tower Pattern musket, the famed ‘Brown Bess’. (Copyright and courtesy of Royal Armouries, Leeds)

On 19 June, and having sent Hompesch ahead in order to advise Ouwerkerk of his intentions, Marlborough gave orders for the army to break camp and begin the long march north to Maastricht. The main body was left under the command of Charles Churchill, whilst the Duke himself rode ahead with the bulk of the cavalry, both columns to rendezvous at Düren, west of Cologne. In atrocious weather Marlborough pushed on and on the 21st he ordered his brother to send the Earl of Orkney with all of the remaining cavalry and a picked force of 10,000 foot to strike out for the rendezvous post-haste. Orkney and Marlborough arrived at Düren some hours apart on 25 June, the exhausted infantry standing proudly to attention as the Captain-General and the cavalry entered the town in their wake. The following day, whilst the mounted troops rested, and the remainder of the army made the rendezvous, Orkney led his column off once more to reinforce Ouwerkerk and assist in the relief of Liège.

Two days later the two wings of the army reunited and, at a council of war, with news coming from Alsace informing them that Villars and Marsin had joined their armies and thrown the Imperialist forces back from their defensive lines around Wissembourg on the Lauter, the two commanders agreed that the Germans would need to shift for themselves and that priority should be given to the recapture of Huy. On 4 July, with Ouwerkerk’s troops moving to Vinaimont as a covering force, the town was invested and, with Villeroi remaining behind his own defensive works and allowing the siege to proceed unmolested, the garrison capitulated after eight days.

Still determined to lay down his baton at the end of the season, Marlborough began to plan an operation that would not only allow him to do so with his reputation intact, but also to leave the Allied Army in a better strategic position than would have ordinarily been the case. His plan called for a surprise attack on the French works near the Château of Wanghe on the Petite Gheete. Screened by extensive marshes, the defensive works were deemed impassable, but Marlborough’s agents informed him of a stone bridge that the French had neglected to destroy. The position itself was defended by a small garrison and was sufficiently distant from its supports to convince Marlborough that it could be taken by surprise and a sufficient force transited to the French bank to dissuade any counter-attack.

After careful preparation, and a campaign of disinformation similar to that which had carried him to the Danube in 1704, Marlborough struck in the early hours of 18 July. Under the cover of darkness, a force of 20 battalions of foot and 38 cavalry squadrons overwhelmed the French position, and quickly formed up for action in preparation for the inevitable enemy response. The Allied commander – the Comte de Noyelles – did not have long to wait and although several French columns were converging upon his position, so was Marlborough, rushing up from the east with the rest of his forces. A general engagement ensued, one in which the Allies had the better of the fighting, and when the British cavalry routed the Bavarian squadrons opposing them, the Comte de Caraman – commanding the Bourbon forces – conducted a fighting withdrawal by forming his infantry into a hollow square and keeping the Allied horse at bay with regular and well-ordered volleys. Fearing that Villeroi and the Elector would be ‘marching to the sound of the guns’, Marlborough was content to let Caraman retreat unmolested.

The two Bourbon commanders had indeed gathered what troops they could but, coming within view of the battlefield and seeing the snaking columns of enemy troops moving toward Wanghe, they realized that the Allies could not be dislodged with the forces they had to hand. Although the French would play down the Allied success as a matter of ‘no strategic importance’, Marlborough had won his victory, gilded as it was, with the capture of five enemy generals, nine colonels and over 60 officers of other ranks, together with ten guns and nine Bavarian colours. It was perhaps the high point of a campaign which soon degenerated into a game of cat and mouse, in which Marlborough continually tried to manoeuvre Villeroi and the Elector into a position from which they would be forced to give battle, whilst those two worthies continually sought to elude the trap, relying on the passage of time and the end of the campaigning season to force the Allies into winter quarters and thereby relinquish many of the gains they had made since the Duke’s return to Flanders.

And then came news that Marlborough had long dreaded – on 16 August, Vendôme had met Eugène in battle at Cassano, north-west of Milan, and although both armies had lost heavily, the battle had been a disaster for the Allies. Firstly, Anhalt-Dessau’s Prussian corps had been decimated in the fighting and was no longer a cohesive formation but, perhaps more importantly, Eugène himself had been badly wounded during the fighting and had had to be withdrawn to Austria for medical treatment. Although Baden had been able to restore the situation in Alsace by late August, the defeat, coupled with the stalemate in Spain and unrest in both Hungary and occupied Bavaria, meant that the available resources needed to be carefully prioritized and, as such, Flanders was not viewed as a critical theatre of operations. Consequently, Marlborough would close the campaign knowing without a shadow of a doubt that his planned campaigning season would have brought the success he had intended and equally certain that, were he to remain in command of the Allied Army in the coming year, he would brook no political interference in his strategy.

Unable to force the enemy commanders into giving battle, and in conflict with many of his Dutch subordinates to whom his aggressive strategy was anathema, Marlborough withdrew towards Tirlemont and after dismantling a large section of the Lines of Brabant, the army continued to move eastwards, encouraging the enemy high command to believe that the failure of the Allies to engage was down to Marlborough’s timidity rather than any action by his subordinates, and with the campaigning season drawing to a close, the Duke left the army under the command of Ouwerkerk and began a diplomatic tour culminating in a visit to Vienna.

At the Imperial Court, Marlborough took part in a series of conferences where he was able to persuade the Emperor to make concessions to the Hungarian rebels in order to redeploy forces to the field against the French. And then, perhaps most important of all, he was able to use his celebrity to secure a line of credit with a number of Austrian financiers so that Eugène would be able to resupply his army and be in a position to take the field in 1706.

From Vienna, Marlborough continued on to Berlin, where he renegotiated a treaty which would see further Prussian troops take the field in Northern Italy and then back to The Hague via Hannover. Throughout his journey, the Duke had – through a combination of compromise and conciliation – been able to paper over a number of cracks that had been appearing in the ranks of the Allies and as he returned to the Low Countries he felt that he now had sufficient support from his coalition partners to pursue what he knew was the right strategy to bring France to her knees and end the war.

During the spring of 1706, and sailing to London Marlborough received support for a plan by which he would leave the Dutch and Imperial troops to contain the enemy in Flanders and on the Rhine, whilst he would march to join Eugène with the remainder of the army and drive the Bourbon forces out of Northern Italy before invading Southern France.

Postcard showing a staff officer of the Bavarian regiment ‘Kurfürst’ c.1700. Coming under Maffei’s command, the regiment fought in the southern sector of Ramillies village, but ultimately broke under pressure from the Dutch Gardes te Voet. (Author’s collection)

Arriving back at The Hague on 24 April, he found that whilst the Dutch had become more conciliatory following correspondence with London, many of the allied princes had now begun to pursue their own agendas – the King of Denmark refused to allow his troops to leave their winter camps until their pay had been fully brought up to date, whilst the rulers of Hesse and Hannover would not allow their forces to serve in Italy whilst the King of Prussia was seemingly preparing to abandon the coalition.

Against this backdrop came the news that Vendôme had beaten the Imperialists at Calcinato on 19 April, and then on 1 May Marsin and Villars combined to attack Ludwig of Baden, driving him back across the Rhine and effectively putting Marlborough’s planned junction with Eugène on hold and forcing the Duke to take the offensive in Flanders in order to regain the strategic initiative.