In terms of casualties inflicted upon the Bourbon Army, the magnitude of Marlborough’s victory remains difficult to quantify. John Millner, who served under the Duke, suggests that Villeroi lost 12,087 dead and wounded with a further 9,729 being taken as prisoners, a figure that is similar to the 20,000 casualties cited by Voltaire. In 1872, Capitaine Marchal quoted a total figure of 13,000 casualties, together with 80 standards, almost all of the artillery and all of the baggage. In more modern works, Chandler cites 12,000 dead and wounded with 7,000 prisoners; Falkner concurs with Chandler’s estimate of the casualties but increases the number of prisoners to around 10,000; whilst Litten, citing French archives, suggests that the French contingent alone lost some 7,000 dead and wounded with around 6,000 being taken prisoner, whilst a possible further 2,000, having decided that ‘discretion is the better part of valour’, simply used the confusion as an opportunity to desert the colours.

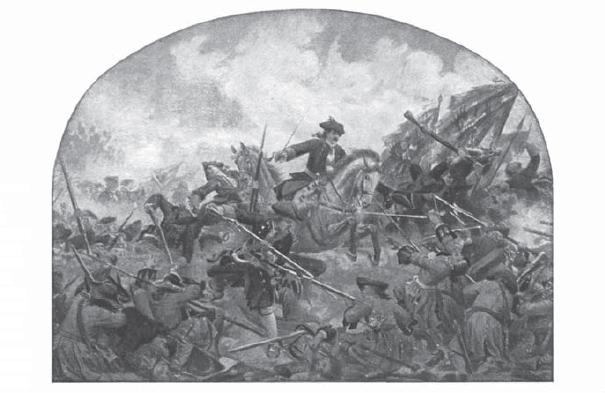

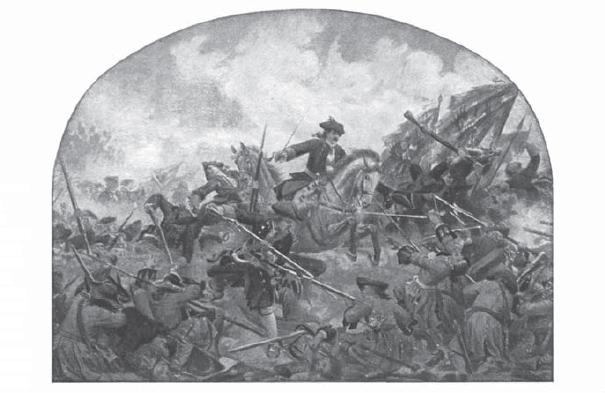

‘The Year of Miracles’. This 19th-century German postcard shows Prince Leopold von Anhalt-Dessau leading Prussian troops into action against the French regiment ‘La Marine’ at Turin on 7 September 1706. Having run out of ammunition the Frenchmen were unable to resist the Prussian attack, and Dessau smashed the Bourbon right flank, securing victory and relieving the three-month siege of the city. (Author’s collection)

In any event, the loss of a possible 20,000 men from an army that had earlier mustered some 60,000 effectives can be referred to only as a disaster, and it would soon be viewed as such at Versailles, as many officers lost no time in writing to their patrons and superiors at Court to exonerate their conduct and damn their peers. But the true scale of the defeat would be illustrated firstly by the fact that, after Ramillies, the Spanish Army of Flanders, and the Bavarian and Cologne ‘armies in exile’ simply ceased to exist, and secondly by the fact that, in so mustering his troops that he could achieve numerical parity with Marlborough, Villeroi had stripped the garrisons of a number of strategically important fortresses, down to almost criminal levels. Thus, whilst the remnants of the Bourbon field army withdrew northwards and then westwards, Marlborough was able to exploit the enemy’s collapse to the fullest.

With Villeroi and the Elector falling back on Ghent and without needing to wait for the siege train to be brought up, Marlborough followed in their wake and, after crossing the Dyle, took Louvain on 25 May. Brussels followed suit two days later and as the army continued its advance, detachments were sent out to summons a number of strategically important towns and cities, perhaps the most significant of which was Antwerp, which surrendered to Cadogan on 5 June, and the bulk of whose predominantly Spanish garrison promptly enlisted in the army of King Charles III. By mid-month there was a very real danger that much of the army might have to be put into garrison in order to maintain the Allied hold on all that had fallen to them in the aftermath of the battle.

Elsewhere, the Allies reported success after success. In Spain, the Bourbons were forced to abandon their siege of Barcelona on 27 April, whilst in Northern Italy, Vendôme was recalled and sent to Flanders in order to shore up the disastrous situation, his place being taken by the Duc d’Orléans and the Marquis de la Feuillade who proceeded to besiege the city of Turin with an army of over 40,000 men. It looked as if the Savoyard capital was doomed, but then on 7 September, Eugène attacked the siege lines with a smaller force and, despite being repulsed three times, the re-formed Prussian corps of Leopold von Anhalt-Dessau smashed through the French lines and scattered the besiegers, one notable casualty being Marshal Marsin who was serving as an adviser to Orléans.

For the Allies, and despite Villars’s continued successes on the Rhine frontier, 1706 had proven to be an annus mirabilis – a year of miracles – the unprecedented, and in some quarters unanticipated, successes of which boded well for a successful conclusion to the war. It was an understandable optimism, but one which would prove to be unfounded as negotiations foundered in the face of the entrenchment of a number of the principals and the conflict would continue for another eight years.