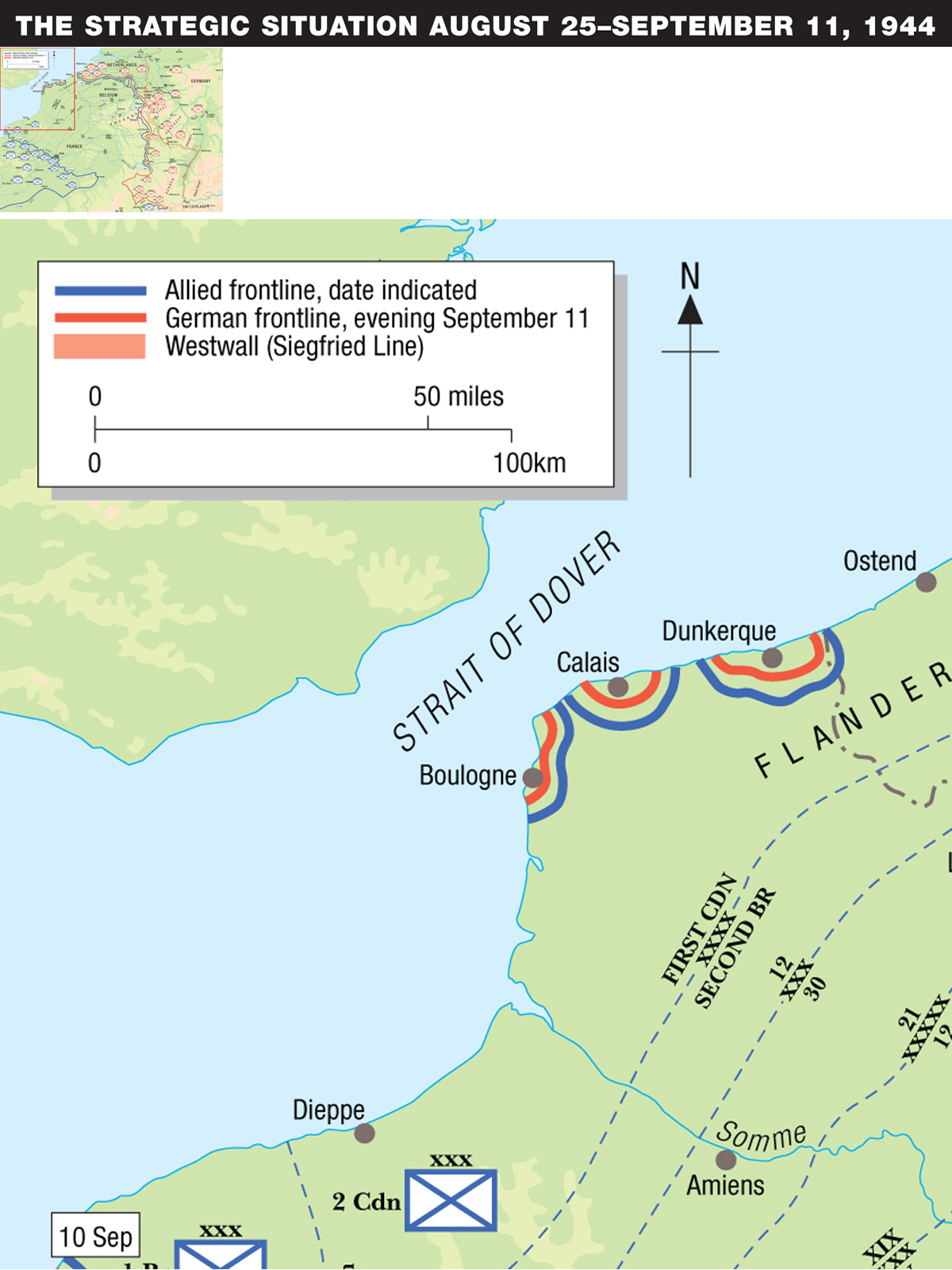

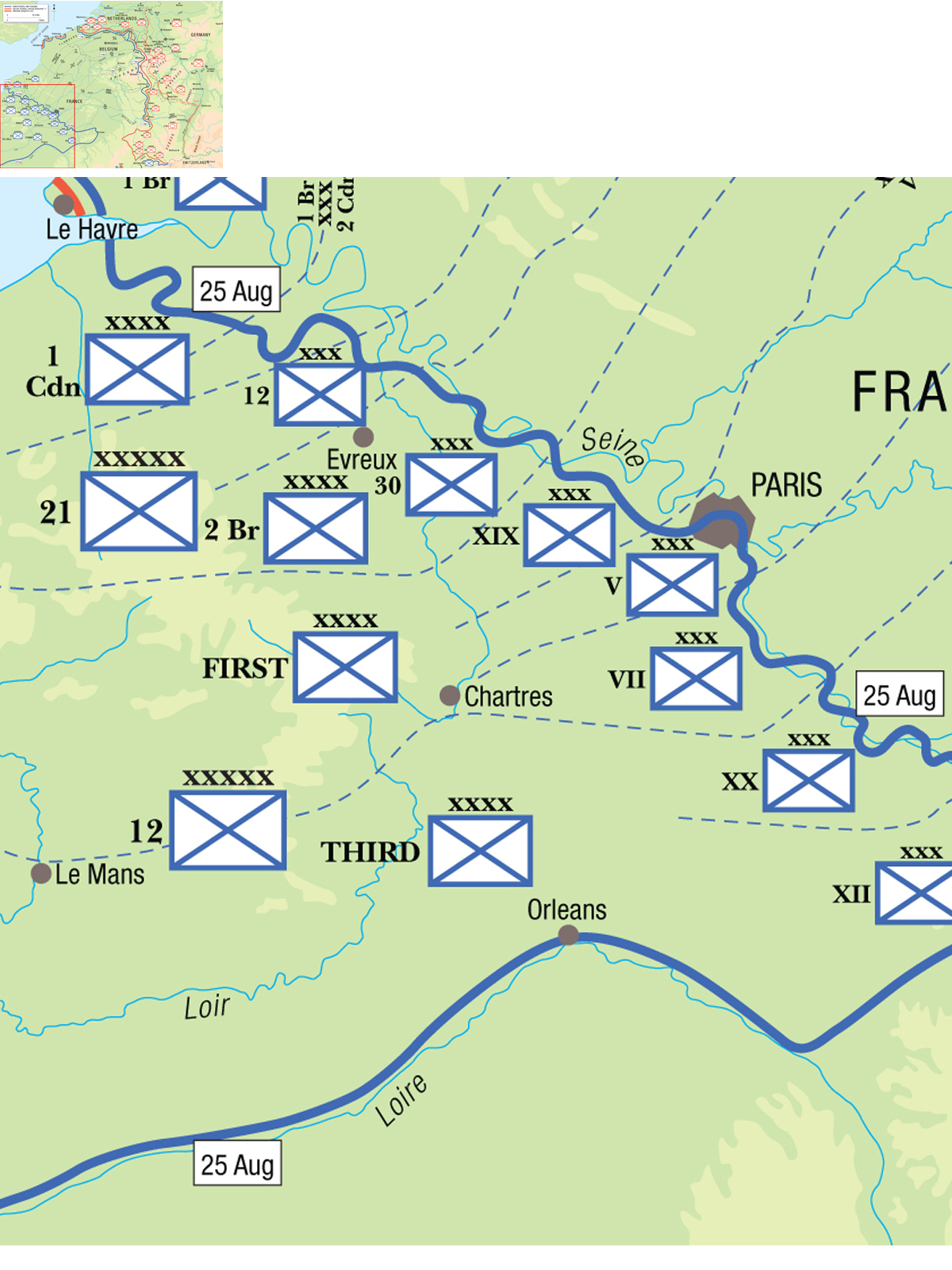

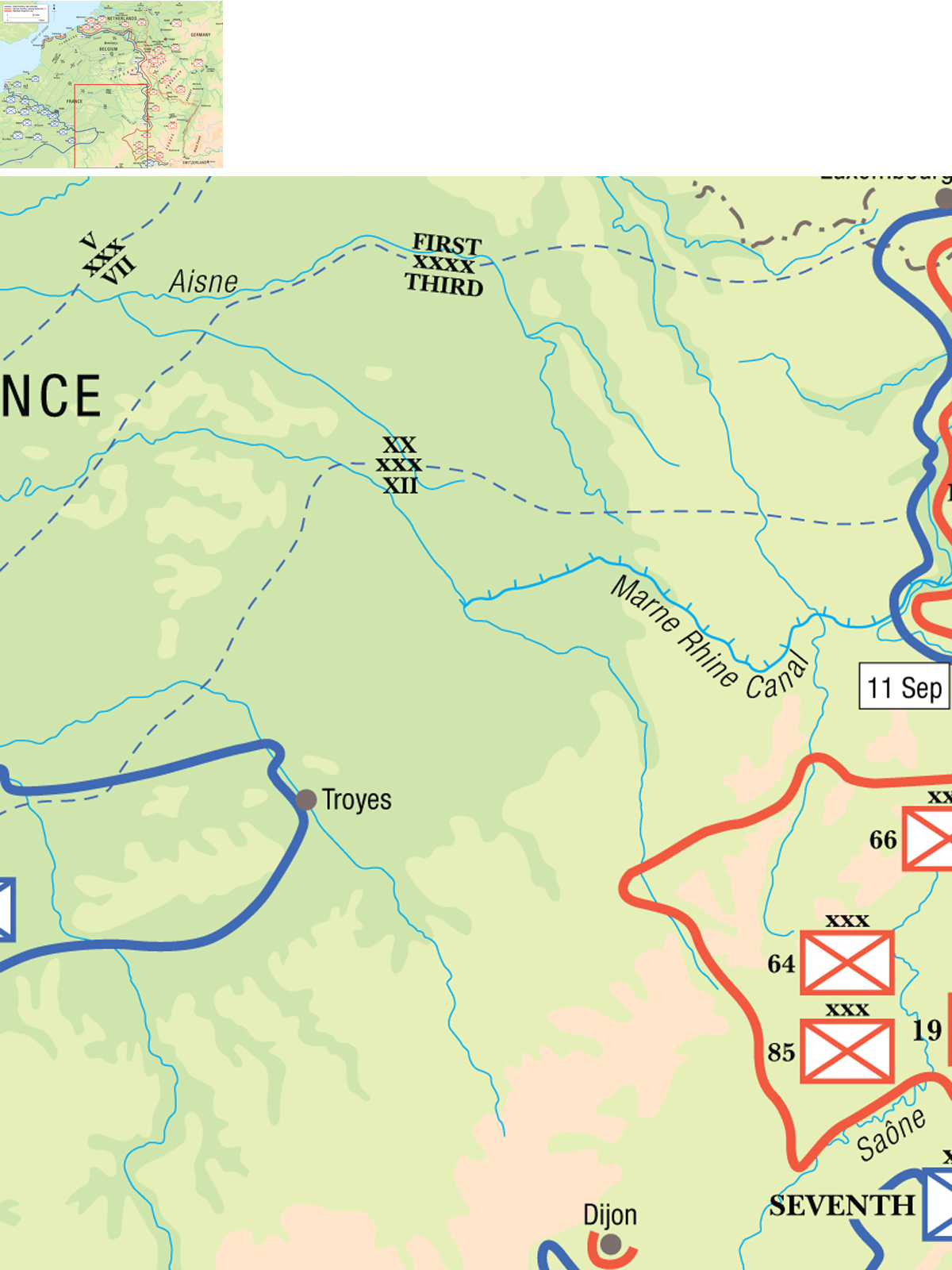

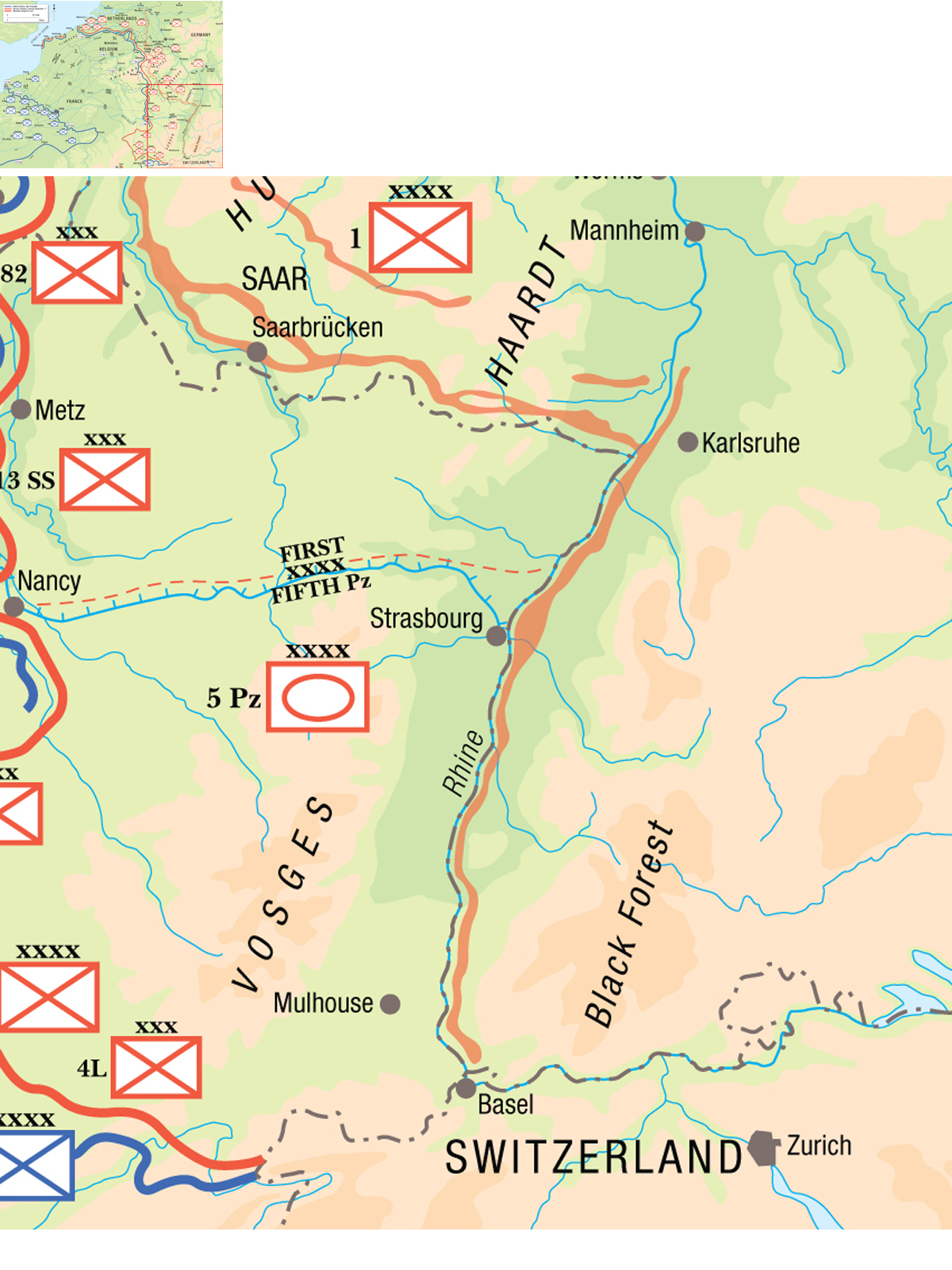

By the middle of September 1944, the Wehrmacht in the west was in a desperate crisis. Following the Allied breakout from Normandy in late July, the German forces in northern France had become enveloped in a series of devastating encirclements starting with the Roncey pocket in late July, the Falaise pocket in mid August, the River Seine in late August, and the Mons pocket in Belgium in early September. The three weeks from August 21 to September 16 were later called the “void” by German commanders as the German defensive positions in northern France and Belgium disintegrated into rout and chaos in the face of onrushing Allied forces. These catastrophes destroyed much of the 7th and 15th armies along with parts of the 19th Army. On August 15, 1944, the US Army staged a second amphibious landing on the Mediterranean coast in southern France. The US Seventh Army raced northward towards Lorraine, threatening to cut off the remainder of German occupation forces in western and central France. As a result, there was a hasty withdrawal of the German 1st Army from the Atlantic coast as well as elements of the 19th Army from central France, precipitously ending the German occupation of France. German losses in the west in the late summer totaled over 300,000 troops, and another 200,000 were trapped in various ports along the Atlantic, such as Brest, Lorient, and Royan.

GIs warily peer around a corner in Thimister, Belgium on September 11, on the way to Aachen. (NARA)

Since their construction in 1938–40, many of the Westwall bunkers had become abandoned and overgrown like this example near Aachen. (NARA)

The situation on the Russian Front was even worse, with Army Group Center having been destroyed at the start of the Soviet summer offensive and the Wehrmacht pushed entirely out of the Soviet Union into Poland and the Balkans. Germany’s eastern alliances collapsed as Finland and Romania switched sides, and in the process the vital Romanian oilfields were lost. The Red Army was already in East Prussia and had advanced as far as the Vistula before running out of steam in August. The Wehrmacht was on the brink of anarchy with commanders unable to halt their retreating troops, and new defense lines manned by inexperienced and untested soldiers. Casualties during the summer had totaled 1.2 million troops and a quarter million horses.

From the perspective of Gen Dwight Eisenhower’s Supreme Headquarters-Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), the strong feeling was that the Wehrmacht was in its death throes, much like the German Army on the Western Front in November 1918. German officers had tried to kill Hitler in July, and it seemed entirely possible that the Wehrmacht would totally collapse. After the stupendous advance of the past month, bold action seemed the order of the day. The otherwise cautious Gen Bernard Montgomery proposed an audacious and imaginative plan to streak through the Netherlands by seizing a bridge over the Rhine at Arnhem. This would propel the 21st Army Group into Germany’s vital Ruhr industrial region, which would effectively cripple the German war industry. Operation Market Garden, a combined airborne-mechanized campaign from Eindhoven to Arnhem, proved to be a disappointing failure. Instead of facing a retreating rabble, the Wehrmacht seemed to grow in strength the closer the Allies approached the German frontier. By the third week of September, it was becoming clear that the Wehrmacht had already reached its nadir and was beginning to recover its ferocious defensive potential. This abrupt change was later dubbed the “miracle of the west.”

The momentum of the campaign in northwest Europe began to slow abruptly in mid September as the Allies outran their supply lines. Initial planning had not anticipated that the Allied armies would advance so rapidly, and logistics were beginning to place a limit on Allied operations. On September 11, 1944, the first day US troops entered Germany, the Allies were along a phase line that the Operation Overlord plans did not expect to reach until D+330 (May 2, 1945) – some 233 days ahead of schedule. While Montgomery was attempting to reach the “bridge too far” at Arnhem, Patton’s Third Army had been forced to halt in Lorraine, even though the path seemed open for a rapid advance on Frankfurt and the Rhine. Allied logistics could only support one major offensive at a time until new supply lines could be established. The rail network through France had been smashed by Allied pre-invasion bombing and many of the French ports had been thoroughly wrecked before the German garrisons had surrendered. Although the British army had seized the vital port of Antwerp largely intact, in the haste to reach the Rhine the vital issue of clearing the Scheldt estuary had been ignored. As a result, German forces could interdict shipping moving down the Scheldt to Antwerp, effectively blocking the port. Antwerp was the natural logistics center for further operations into Germany, and until the Scheldt could be cleared, Allied operations would have to operate on a thin stream of supplies. The failure to clear the approaches to Antwerp during the Wehrmacht retreat in early September proved to be one of the greatest Allied mistakes in 1944.

The German situation in the early autumn of 1944 was still desperate, but as the Wehrmacht reached the German frontier, the summer panic subsided and a sober stoicism returned. It was one thing to give up Holland and Belgium without a fight, but the western region of Germany was another matter altogether. By the time that the retreating survivors of Army Group B reached the frontier, new defenses had already been stitched together along the Siegfried Line using replacement units, local training units, and an assortment of rear-area troops. In open combat against Allied mechanized formations, such defenders stood little chance. But the German frontier was well suited to defense. The terrain was a mixture of industrial towns bisected by numerous rivers and interspersed with wooded forests and hills, such as the Reichswald and Hürtgenwald. The autumn of 1944 was unusually wet; almost double the usual quantity of rain fell. The mud dampened the chances for Allied mechanized operations and the overcast skies constrained air-support operations.