Generalfeldmarschall (GFM) Gerd von Rundstedt returned to command the OB West (Oberbefehlshaber-West, or Supreme Command West) on September 5, 1944, having been relieved of the same post on July 1 over disagreements with Hitler about operations in France. Rundstedt was widely respected throughout the army for his leadership during the key Blitzkrieg campaigns and his reappointment was meant to reassure the troops after the harrowing defeats of the summer. His principal subordinate was GFM Walter Model, who had held the dual posts of OB West and commander of Army Group B following the suicides of Günther von Kluge, the previous OB West, and Erwin Rommel, the former Army Group B commander – both deaths connected with the July 20 plot against Hitler. Following Rundstedt’s reappointment, Model remained as the Army Group B commander, responsible for the forces in northwestern Germany and Holland. Model was a complete contrast to the gentlemanly and aristocratic Rundstedt. He was a brash and ruthless upstart, Germany’s youngest field marshal, and one of Hitler’s favorites for his uncanny ability to rescue the Wehrmacht from its deepest disasters. Model had been sent to the Russian Front in the summer of 1944 to help reestablish defensive lines after the crushing defeat of Army Group Center by the Red Army’s Operation Bagration, a miracle that helped stall the Soviet summer offensive in Poland. Now he was expected to do the same in front of Aachen.

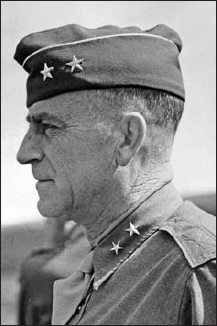

GFM Walter Model commanded Army Group B and he is seen here with Gen Maj Gerhard Engel, commander of the 12th Infantry Division. (MHI)

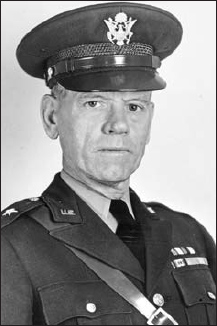

The Aachen corridor was defended by the 7th Army, commanded by Gen Erich Brandenberger. Model derided him as “a typical product of the general staff system” and his traditional style did not earn him the favor of Hitler. Yet Brandenberger had a fine combat record, leading the 8th Panzer Division during the invasion of Russia in 1941 and commanding the 29th Army Corps in Russia for a year before being given command of the 7th Army.

General der Panzertruppen Erich Brandenberger commanded the 7th Army through the Ardennes campaign. (MHI)

One of Brandenberger’s initial tasks was to restore some measure of order amongst his edgy corps and divisional commanders. The “void” of late August and early September had left many divisional commanders to operate on their own initiative and it was Brandenberger’s task to reestablish iron discipline. A good example of the confused temper of the time was the fate of the highly respected but headstrong commander of the 116th Panzer Division, Gen Lt Graf Gerhard von Schwerin. The young count already had a reputation for being more concerned about the fate of his troops than for instructions from higher headquarters, and during the abortive Panzer counteroffensive around Mortain in the summer, had been relieved for flaunting instructions on the disposition of his division. Following the Falaise debacle, he was reappointed commander, but, during the short-lived defense of Liège, he again frustrated the corps commanders by his independent actions. It was well known among the divisional officers that Schwerin did not want to continue fighting on German soil for fear of the desolation that would ensue. When Schwerin first took command of the Aachen defenses on September 12, he found that Nazi party leaders and police had already abandoned the city and that the civilian population was in chaos; he halted the exodus out of the city, not realizing that it had been Hitler who had ordered it. Hoping that the city would be abandoned rather than defended to the last, he left a message with a city official intended for the US Army asking them “to take care of the unfortunate population in a humane way.” Unfortunately, on September 15 the Nazi party leaders and some police skulked back into the city and discovered the note. They accused Schwerin of defeatism and tried to haul him before a “People’s Court.” Schwerin ignored them and later in the month presented himself to Seventh Army headquarters for a military tribunal. Appreciating Schwerin’s gallantry, Rundstedt proposed reinstating him to divisional command. However, in the paranoid climate around Hitler after the officers’ bomb plot, he was sent for a while to the “doghouse” – the OKW officers’ pool – until things cooled off. He later commanded a Panzergrenadier division and a corps in Italy. Brandenberger also relieved Gen Schack of command of 81st Corps on September 20 due to his connection with the Schwerin affair.

Gen Lt Graf Gerhard von Schwerin commanded the 116th Panzer Division during the initial defense of Aachen. (NARA)

At the beginning of September 1944, Bradley’s 12th Army Group included two armies, Hodges’ First and Patton’s Third. Bradley had headed the First Army when it landed in Normandy, and was bumped upstairs once Patton’s Third Army was activated in August 1944. Hodges had been Bradley’s chief of staff in the First Army and succeeded him. Much like Bradley, Hodges was a quiet professional, and so very much unlike the flamboyant George S. Patton. However, Hodges did not have Bradley’s intellectual talents and had flunked out of the US Military Academy, making his way up the command ladder through the ranks. He was in Bradley’s shadow for much of the war, and many senior officers felt he gave too much power to his dynamic chief of staff, Maj Gen William Kean. Hodges was an infantryman with a dependable but stolid operational style.

Lt Gen Courtney Hodges, commander of the US First Army. (NARA)

At the time of the Aachen fighting, Hodges had three corps: Gerow’s V Corps, Collins’ VII Corps and Corlett’s XIX Corps. Like Hodges, Maj Gen Leonard Gerow was older than both Bradley and Eisenhower, coming from the Virginia Military Institute class of 1911. He commanded Eisenhower in 1941 while heading the War Plans division of the general staff, and he led V Corps during the D-Day landings on Omaha Beach. He was a quintessential staff officer with a tendency to micromanage his divisional commanders, and so was a comfortable fit with the First Army commander. When Hodges needed more tactical flair, he turned to Maj Gen Lawton “Lightning Joe” Collins. He had commanded an army division on Guadalcanal in 1943, and had proven to be an imaginative practitioner of mechanized warfare in France. Collins had executed the most impressive US Army successes of the summer, the envelopment of Cherbourg in June and the Operation Cobra breakout in July. Although he had a very different tactical sensibility to Hodges, they proved to be a complementary team through the war. The third corps commander, Maj Gen Charles “Cowboy Pete” Corlett was the odd man out in the First Army. He had commanded army units in the Aleutians in 1943 and on Kwajalein in 1944, and was brought to Europe in the hope that some of his amphibious experience would rub off on D-Day planners. He was widely ignored, and as a result, he had a chip on his shoulder over his continued lack of influence within First Army. For example, he had pointedly recommended increasing the artillery ammunition allowances based on his own experience, only to be proven right in the autumn when US Army ammunition reserves proved to be woefully inadequate. Corlett had several angry exchanges with Hodges and his staff, and was relieved during the Aachen campaign for “health reasons” – in fact this was due to his disputatious relations with Hodges. He had hardly arrived back in Washington for rest when he was bundled off to the Pacific again for another corps command, so high was his reputation in that theater.

Maj Gen Leonard Gerow, commander of V Corps. (NARA)

Maj Gen Charles “Cowboy Pete” Corlett, commander of XIX Corps. (NARA)

First Army was blessed with an array of superior divisional commanders such as Huebner with the 1st Infantry, Harmon with the 2nd Armored, Rose in the 3rd Armored, Barton in the 4th Infantry, and many more. One of the divisional commanders was new, Norman Cota of the 28th Division. He had commanded the 116th Regimental Combat Team of the 29th Division on Omaha Beach on D-Day and his exceptional leadership that day earned him command of the 28th Division. The tragic fate of the 28th Division, first in the Hürtgen forest in October 1944 and then in the Ardennes in December, would haunt his career.

Maj Gen Lawton “Lightning Joe” Collins, commander of VII Corps. (NARA)

When Simpson’s Ninth Army arrived in late September, Bradley placed it adjacent to the British 21st Army Group. Bradley was aware of Montgomery’s tendency to poach US forces to make up for his own shortages, and he did not want his more experienced divisions in the First Army transferred to British control. Ninth Army was fairly small during the Aachen campaign, with only a single corps for much of the time.