The complete collapse of the Wehrmacht after the disasters in Belgium in early September 1944 was partly averted by absorbing territorial and training units once its battered divisions reached Germany. The Wehrmacht consisted of both a Field Army, which controlled tactical combat units, and a separate Replacement Army (Ersatzheer) within Germany itself. In desperation, the untrained units from the reserve training divisions and sometimes even the staffs of the training schools were thrown into combat. Each military district also had several Landesschützen battalions for territorial defense, local home guard units made up of men “as old as the hills” armed with aging rifles, and usually commanded by World War I veterans.

Another source of personnel for the army was the Luftwaffe, since many of its ground personnel were freed from their usual assignments by the growing fuel shortage that grounded many aircraft in the autumn of 1944. While some men were absorbed directly into replacement units, others were organized into Luftwaffe fortress battalions. These battalions were not necessarily assigned to the Westwall bunkers; they were so named because their troops had little infantry training and were poorly armed, and so were useful only for holding static defense positions. These units were not well regarded by the army due to their tendency to retreat on first contact with enemy forces, and in subsequent months the army preferred to simply absorb excess Luftwaffe and navy personnel directly into army units.

Older men were swept into the army to make up for shortages. This old Landser was captured near the town of Hürtgen in early December 1944. (NARA)

The unification of command of these disparate units did not take place until early September, with the reconstitution of the 7th Army. Following the encirclement in the Falaise pocket and the deeper envelopment on the Seine, the German 7th Army ceased to exist and its remnants were attached to the 5th Panzer Army. On September 4, 1944, it was reconstructed under Gen Erich Brandenberger and assigned the task of defending the Westwall in the Maastricht–Aachen–Bitburg sector, with its 81st Corps covering from the Herzogenrath–Düren area, the 74th Corps from Roetgen to Ormont and the 1st SS-Panzer Corps in the Schnee Eifel from Ormont to the 1st Army boundary near Diekirch. The 81st Corps covered the sector attacked by the US VII and XIX Corps and most of its main combat elements were still withdrawing through Belgium into the second week of September. The 353rd Infantry Division had little more than its headquarter elements, so the 81st Corps used it to man the Westwall defenses in the Aachen area by assigning it the various Luftwaffe and Landesschützen battalions. The northern sector facing the US XIX Corps was held by two significantly understrength infantry divisions, the 49th and 275th. The 49th Infantry Division had been trapped in the Mons pocket, and by the time it reached the German frontier it had only about 1,500 men, mostly from the headquarters and support elements. The 275th Infantry Division suffered terribly in Normandy and by August it was described as “practically destroyed.” It was partly rebuilt and by mid September had only one infantry regiment. It had a divisional strength of 5,000 men and a combat strength of about 1,800 men but its field artillery was limited to a single battery of 105mm howitzers.1

The Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine proved to be a useful reservoir of personnel to help in the autumn rebuilding of the army. This young soldier captured in Aachen wears the decorations of an S-boat (E-boat) torpedoman, presumably from one of the squadrons on the Atlantic coast.

The principal units facing the US VII Corps were the 116th Panzer Division, centered around Aachen, and the 9th Panzer Division in the Stolberg corridor. The 116th Panzer Division was the best-equipped unit in this sector, but, when it took control of the defense of Aachen in mid September, it had a combat strength of about 1,600 men, with its Panzergrenadier battalions about half-strength and only three PzKpfw IV tanks, two Panther tanks, and two StuG III assault guns. Reinforcements in the third week of September reestablished its combat strength in infantry, but it was down to only about 2,000 liters (500 gallons) of fuel, leaving it immobilized. The 9th Panzer Division was still withdrawing through Belgium and was a mere skeleton. Its armored strength had been reduced to eight operational Panther tanks, and six StuG III assault guns; its two Panzergrenadier regiments were down to about three companies. The division was so weak that the 7th Army reinforced it with the remnants of Panzer Brigade 105, which had lost most of its Panzergrenadiers and was down to five Panther tanks and three assault guns. After the surviving battlegroup withdrew across the frontier, the division was rebuilt with a hodgepodge of territorial and Luftwaffe units in its sector.

Recognizing the weakness of the units assigned to the 81st Corps, the 7th Army attempted to reinforce the Aachen sector as soon as resources became available, and three divisions were assigned in mid September. The first to arrive was the 12th Infantry Division, which had been reconstituted in East Prussia in the late summer after heavy combat on the Russian Front. Its arrival in the Aachen sector starting on September 14 was a major morale boost for the locale civilian population, as the division was fully equipped with young, new soldiers. The two other divisions were the 183rd and 246th Volksgrenadier divisions (VGD). The 183rd VGD arrived in the sector on September 22 and was assigned to take over the Geilenkirchen sector from the 275th Infantry Division, which was then shifted to cover a gap on the corps’ southern wing in the Hürtgen forest. The 183rd VGD was moved from Bohemia starting on September 23. Its arrival permitted the 116th Panzer Division to be gradually pulled out of the line for refitting and to serve as the corps reserve.

One of the most effective weapons in the autumn 1944 fighting was the PaK 40 75mm antitank gun, the standard weapon of German infantry divisions and frequently misidentified by US troops as an 88mm gun. This example was captured in the fighting near Aachen. (NARA)

| 7th Army | General der Panzertruppe |

| Erich Brandenberger | |

| 81st Corps | Generalleutnant Friederich-August Schack |

| 49th Infantry Division | Generalleutnant Siegfried Macholz |

| 275th Infantry Division | Generalleutnant Hans Schmidt |

| 116th Panzer Division | Generalleutnant Graf Gerhard von Schwerin |

| 9th Panzer Division | Generalmajor Gerhard Müller |

| 353rd Infantry Division | Generalleutnant Paul Mahlmann |

| Reinforcements after September 14 | |

| 12th Infantry Division | Colonel Gerhard Engel |

| 183rd Volksgrenadier Division | Generalleutnant Wolfgang Lange |

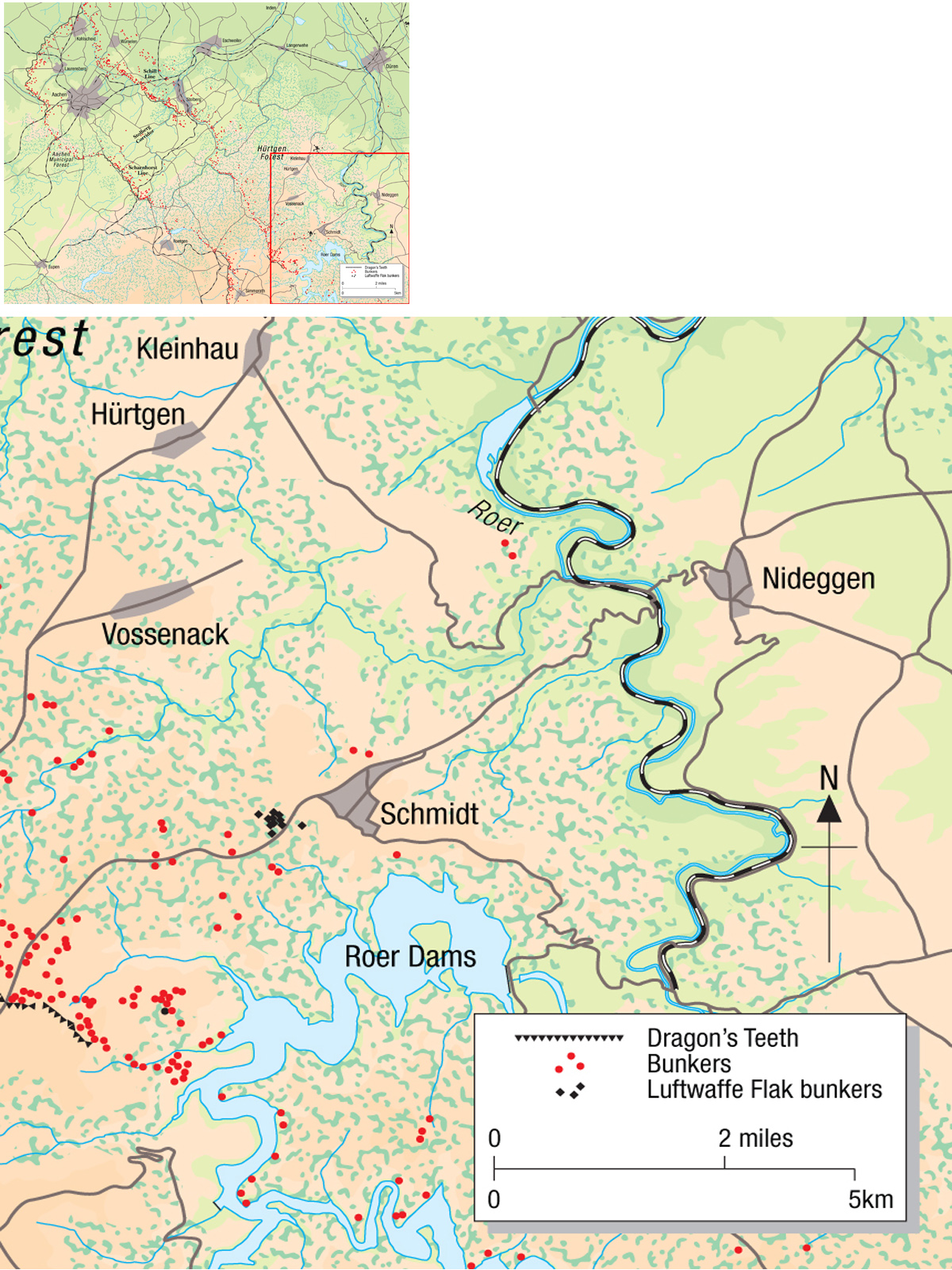

The Westwall program began in 1938, but the role of the Westwall was fundamentally different from the much more elaborate Maginot Line nearby in France. It was intended as a defensive fortified zone facilitating offensive action. By 1938, Hitler was already planning military actions against Czechoslovakia and Poland, and fortifications played a vital part in these plans. The Westwall could be held by a modest number of second-rate troops while the bulk of the Wehrmacht was deployed in combat to the east. The initial construction program ignored the Aachen area, since it faced neutral Belgium. Once the section facing central France was complete, Hitler decided to extend the Westwall along the Belgian frontier due to concerns that the French could deploy their mobile forces through Belgium.

A typical stretch of the Westwall with rows of dragon’s teeth in the background covered by an armored machine-gun position. These cupolas were the only visible portion of a much more extensive infantry bunker underneath. (NARA)

This armored machine-gun cupola from the Westwall near Wahlerscheid is typical of the type of defenses built in the forests along the German frontier, positioned to cover firebreaks and other access routes through the forest. (NARA)

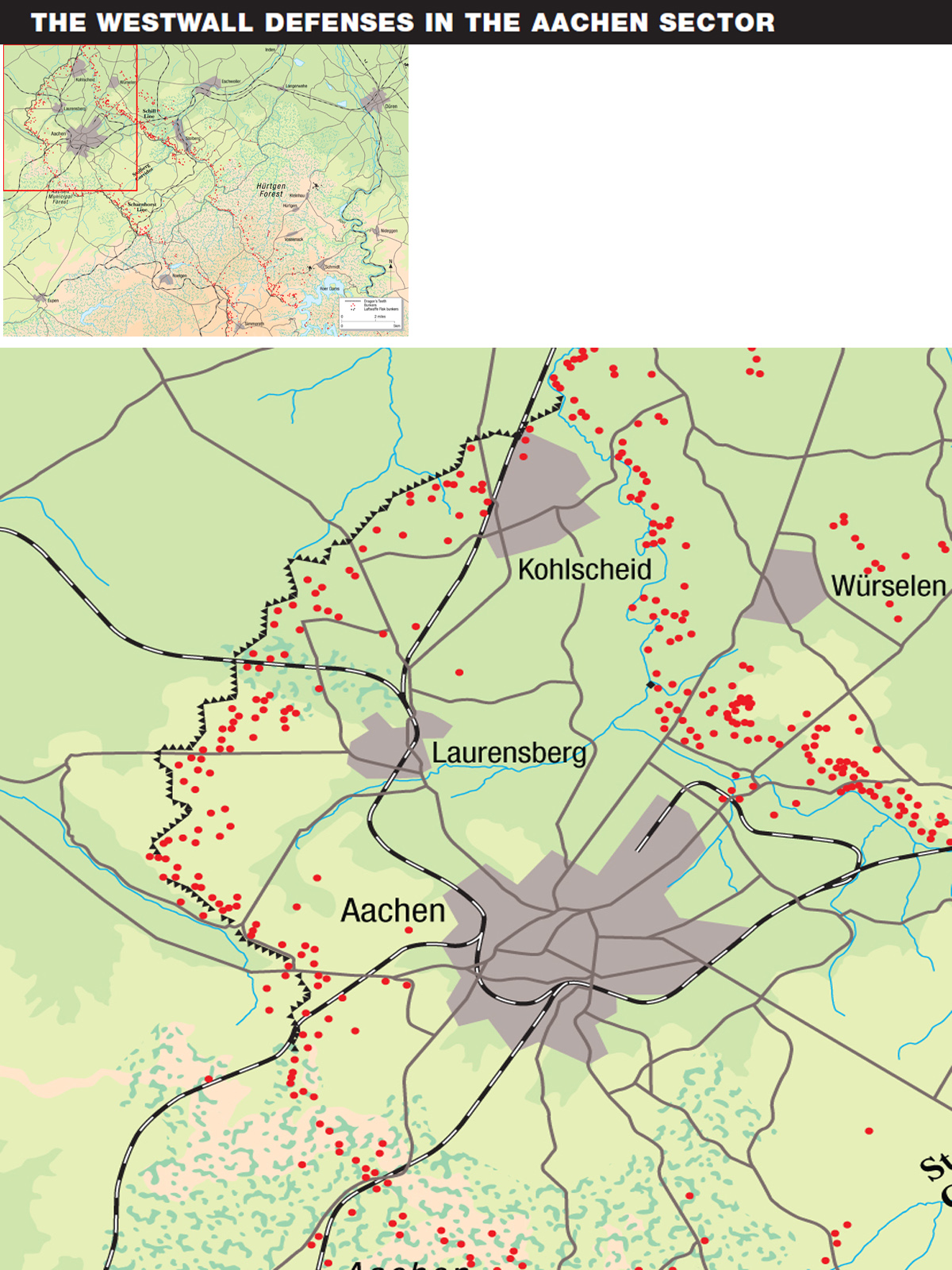

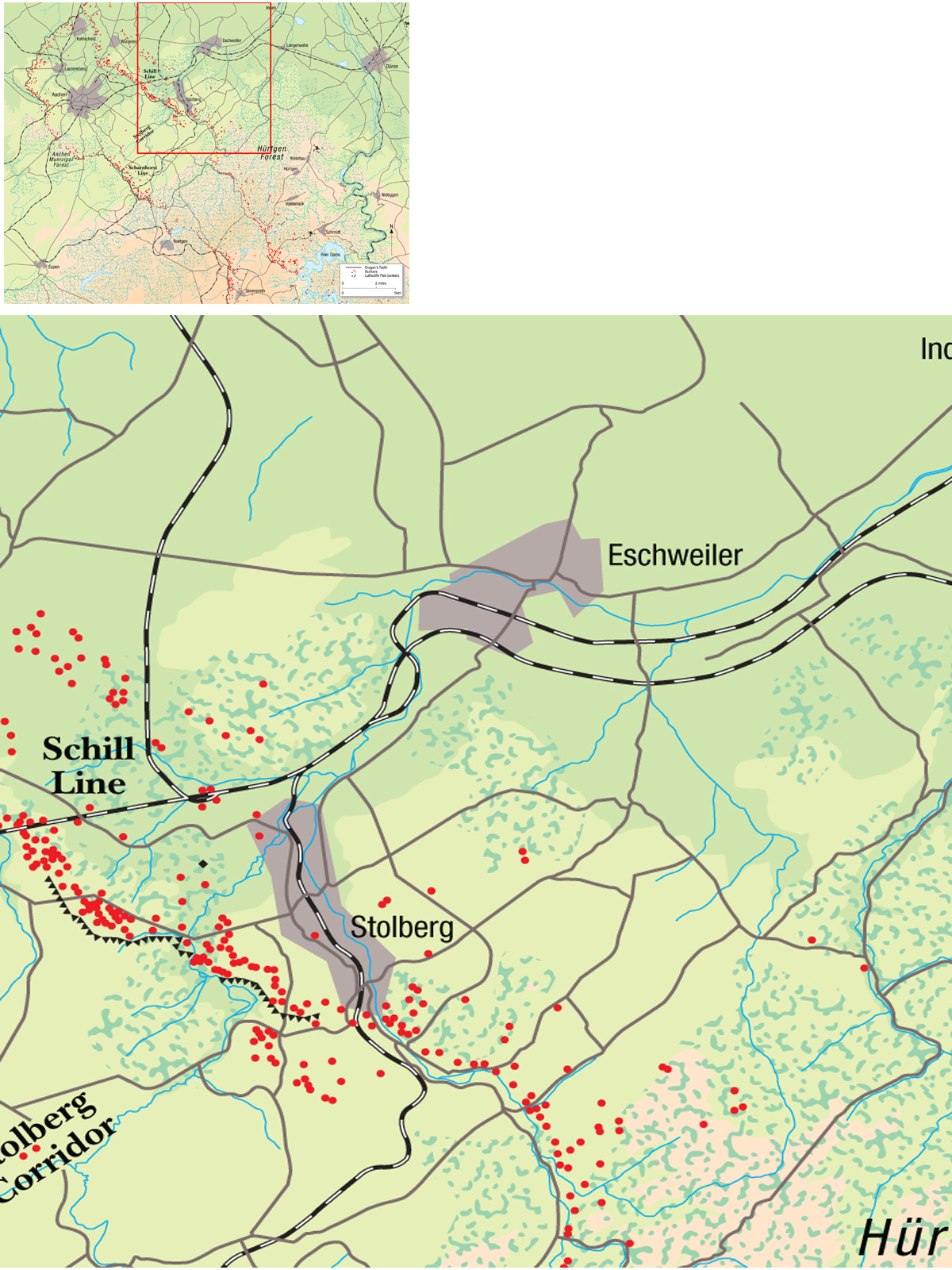

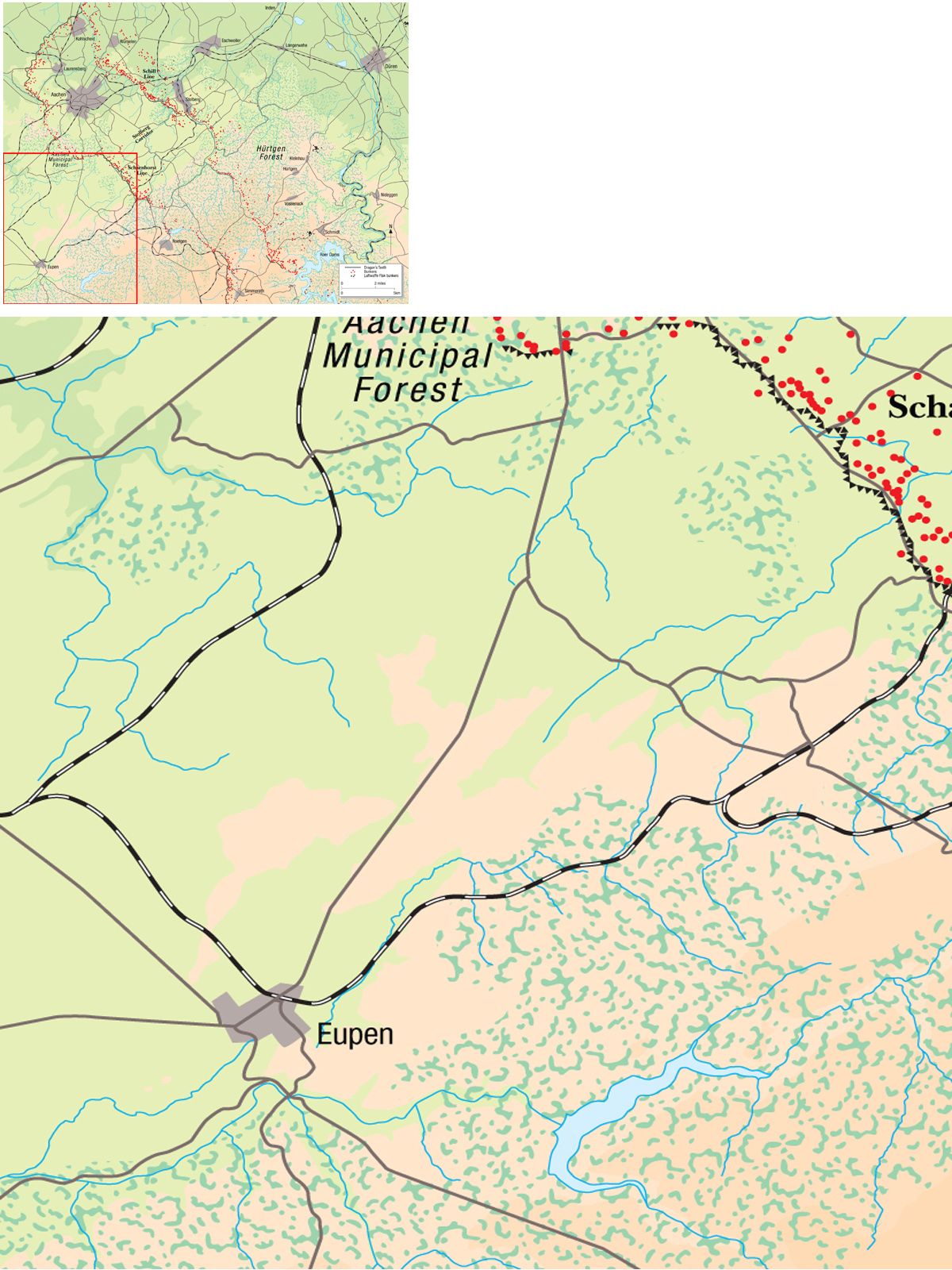

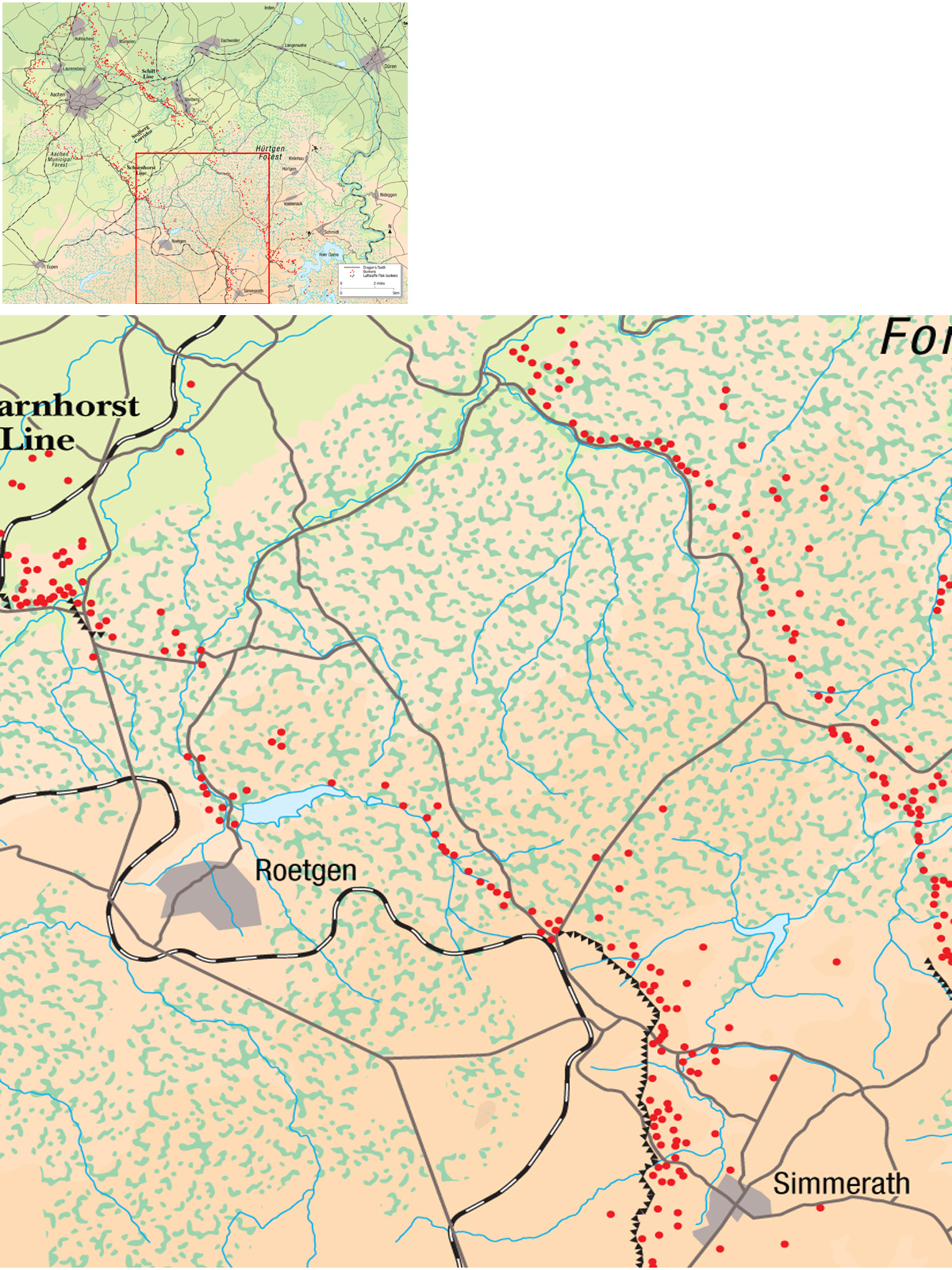

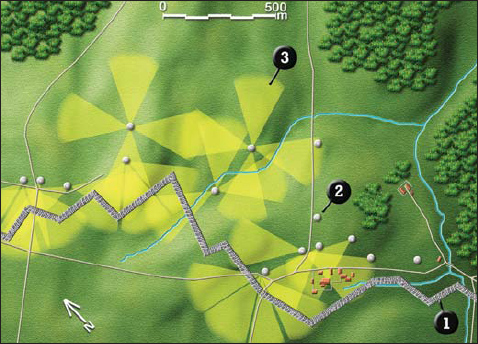

The Westwall in the Aachen area, called the Düren Fortification Sector (Festungsdienststelle Düren) was one of only two sectors with a double set of defensive lines. The other was in the Saar, which like the Aachen corridor was one of the traditional invasion routes between France and Germany. The initial defensive line was called the Scharnhorst Line and was located about a kilometer behind the German border. A second defensive belt, called the Schill Line, was created to the east of Aachen. The Westwall was a far less elaborate defensive system than the Maginot Line. With few exceptions, the fortifications were relatively small infantry bunkers with machine-gun armament, and few of the elaborate artillery bunkers that characterized the French defenses. There was never any expectation that the Westwall alone could hold out against a determined enemy, but after the experiences of trench warfare in World War I, there was a clear appreciation that modest fortifications could amplify the defensive capabilities of the infantry. The Westwall began with a barrier of antitank ditches and concrete dragon’s teeth antitank obstacles. The layout and density of the subsequent bunkers depended on the geography and were designed to exploit local terrain features. Machine-gun bunkers were placed to cover all key roads and approaches as well as to prevent the antitank obstacles from being breached. Antitank bunkers were equipped with the 37mm antitank gun – adequate in 1939 but obsolete in 1944. Another characteristic type of bunker was a forward observation post for artillery spotters, connected to the rear to take maximum advantage of artillery firepower in defending the frontier. In the Aachen area, the Westwall had a linear density of about 60 bunkers per 10km stretch. Some idea of the relative distribution of the bunkers can be seen in the following table of the Düren Fortification Sector, which included the Aachen area.

While many bunkers used natural camouflage, some were cleverly blended in with neighboring buildings, such as this bunker camouflaged to resemble an ordinary house in Steinfeld. (NARA)

By 1944, the Westwall bunkers had become overgrown and well camouflaged, like this one in the woods outside Aachen encountered by the 1st Infantry Division. (NARA)

This schematic shows a typical stretch of the Westwall near Aachen in the area first penetrated by the 1/26th Infantry. The dragon’s teeth (1) were positioned in front, with a string of bunkers behind (2); the bunker’s machine guns provided overlapping fields of fire (3). (Author’s illustration)

| Düren Fortification Sector | ||||

| Type | Infantry | Antitank | Artillery | Total |

| Main belt | 1,413 | 128 | 109 | 1,650 |

| Other | 814 | 123 | 138 | 1,075 |

| Total | 2,227 | 251 | 247 | 2,725 |

| Accommodation | 31,253 | 1,533 | 3,544 | 36,330 |

During 1943–44, the Westwall was stripped of anything removable such as wire obstructions, armored doors, gun mounts and armored fittings to equip the Atlantikwall against the impending Allied invasion. As a result, when the Wehrmacht retreated into Germany in September 1944 the Westwall was overgrown and largely abandoned. There was a hasty effort to refurbish the defenses in August–September 1944.

The US Army by the time of the Siegfried Line campaign had moved beyond its growing pains and had become an experienced and highly capable force. First Army included some of the most experienced US units in the ETO, such as the 1st Infantry Division and 2nd Armored Division, which had served in North Africa, Sicily, and Normandy; nearly all of the other divisions had been in combat since July. Combat leaders were experienced and battle hardened. For example, in a typical regiment – the 22nd Infantry of the 4th Division – officer casualties from D-Day to the start of the Hürtgen fighting in November had been 283 from an authorized strength of 152; 40 percent of its officers had been wounded and returned to service, and 12 of its lieutenants were battlefield commissions. It was a similar story in the enlisted ranks: the 22nd Infantry had suffered 4,329 casualties since D-Day out of an authorized strength of 3,100. The US Army had not yet begun to suffer the serious shortages in infantrymen caused by the autumn and winter 1944 fighting, so infantry divisions tended to operate near full strength. The US Army continued to feed replacements into the divisions in combat, and, while rifle companies were often understrength during intense battles, they seldom became as depleted as German rifle companies in 1944. US Army replacement policy has often been criticized as inefficient compared to the German system, but this traditional viewpoint has been seriously questioned by more recent scholarship on the subject.2

One of the most effective weapons during the Siegfried Line campaign was the M12 155mm GMC, seen here during the fighting in the Hürtgenwald near Gürzenich on November 16. It was used for bunker busting along the Westwall, and also during the urban fighting, such as in Aachen. (NARA)

The US infantry divisions had adapted well to the changing terrain and tactical demands of the ETO, from the hedgerow country of Normandy in June and July, the pursuit operations of August, and the fortification and urban fighting of September–October. In contrast, the Hürtgen forest fighting proved to be especially costly and frustrating for the infantry. In many respects, the forest fighting was an aberration due to the lack of tactical flexibility at the lower levels forced on the infantry divisions by the orders of higher headquarters. The divisions fought on extended frontages in difficult weather and terrain conditions with little or no tank support, poor logistical support, and little opportunity to maneuver. Artillery was the main killer on both sides, and the US infantry was at a distinct disadvantage due to its offensive posture. Advancing American infantrymen were far more vulnerable to artillery air-bursting in the trees overhead than the defending German infantry in log-protected dugouts. As a corollary, the usual US advantage in divisional field artillery did not apply in the Hürtgen forest, in spite of US advantages in ammunition supply and fire direction because of the decreased lethality of US artillery when used against protected German infantry dugouts in heavily wooded areas.

Anticipating the Siegfried Line, in September 1944 the First Army brought up flamethrowers to deal with the bunkers. (NARA)

GIs hold a defensive position in the Hürtgen forest on November 17. The M1 57mm antitank gun was the standard antitank gun in infantry divisions in 1944, with 18 in each infantry regiment. However, it was not particularly effective against the newer German tanks such as the Panther. (NARA)

The US armored divisions fought as combined-arms formations, amalgamating their tank, armored infantry, and armored field artillery battalions into three battlegroups called combat commands. Two of the divisions in the First Army, the 2nd and 3rd Armored divisions, were under the old 1942 tables of organization and so had six instead of the later 1943 pattern of three tank battalions. Although stronger in tanks than the other “light” armored divisions, the imbalance in tanks created a need for more infantry and it was the usual practice to attach infantry battalions from neighboring infantry divisions to the combat commands during operations. The standard US tank of this period was the M4 “Sherman” medium tank, mostly with a 75mm dual-purpose gun but with an increasing number of 76mm guns optimized for the antitank role. The M4 was the best tank in combat in 1943 in North Africa, but by 1944 its time had passed and it was inferior to the better German tanks, such as the Panther, in terms of firepower and armor protection. This disparity was not especially significant in the Siegfried Line fighting, since there were so few German tanks present. However, the M4 had only moderate armor, which did not offer adequate protection against the most common German antitank gun, the 75mm PaK 40, or against infantry Panzerfaust antitank rockets, which were the main tank killers in the autumn fighting.

The summer campaign had been costly to the US armored divisions in both men and equipment, and many of the divisions were ragged and exhausted after nearly three months of continual combat. Tank losses during the August pursuit were the highest experienced by the US Army in Europe up to that time and were only surpassed during the Battle of the Bulge. The US Army had underestimated the likely loss rate of tanks in combat based on the experience in North Africa and Italy and so had only allotted a monthly attrition reserve of 7 percent compared to the British reserve of 50 percent. As a result, US tank units in the autumn typically fought at about 80–85 percent of authorized strength until the newly established attrition factor of 15 percent caught up. Some units had higher than average losses, and so, for example, in mid September 1944 the 3rd Armored Division was fighting with about half of its authorized tank strength.

In the miserable rain and mud of autumn, one of the most useful vehicles was the tracked M29 Weasel, seen here pulling a jeep out of the mud during the fighting in the Hürtgenwald in October 1944.

A more serious supply deficit was in artillery ammunition, which had been substantially underestimated and as a result there was a shortage through most of the autumn. However, these shortages should be put in perspective, as by German standards US equipment and ammunition usage was luxurious. The Germans estimated that the US Army fired more than double the artillery ammunition that they did; Panzer strength in the autumn of 1944 was seldom above half of authorized strength.

The sole combat arm where the US Army clearly enjoyed both technological and tactical superiority was in field artillery. US infantry divisions had three 105mm battalions, which could be tasked to support each of the three infantry regiments in the division, plus a 155mm howitzer battalion for general support. While the cannons were not that much better than their German counterparts, they were fully motorized, and ammunition supply tended to be more ample with some rare exceptions. US artillery fire direction was a trendsetter, using a fire direction center (FDC) at divisional and corps level, linked by excellent tactical radios to mass fires. This facilitated novel tactics such as time-on-target (TOT) where all the cannon in a division or corps were timed for their first projectiles to arrive in a concentrated “serenade” on a single target almost instantaneously, greatly amplifying the lethality of the barrage since the enemy had no time to take cover. US corps artillery tended to include heavier weapons, not only additional 155mm howitzer battalions but also long-range 155mm guns, 8in. howitzers, and even the occasional 240mm howitzer battalion.

One of the main advantages the US Army possessed in the summer 1944 campaign had been tactical air support. The US First Army and the Ninth Tactical Air Force had worked out successful command and control to permit extremely effective frontline support by fighter-bombers, which was especially useful for disrupting German logistical support. US tactical air support proved far less effective in the autumn of 1944 due to poor weather, which frequently hindered or prevented air operations.

| First Army | Lt Gen Courtney Hodges |

| V Corps | Maj Gen Leonard Gerow |

| 4th Infantry Division | Maj Gen Raymond Barton |

| 28th Division | Maj Gen Norman Cota |

| 5th Armored Division | Maj Gen Lunsford Oliver |

| VII Corps | Maj Gen Lawton Collins |

| 1st Infantry Division | Maj Gen Clarence Huebner |

| 9th Infantry Division | Maj Gen Louis Craig |

| 3rd Armored Division | Maj Gen Maurice Rose |

| XIX Corps | Maj Gen Charles Corlett |

| 30th Division | Maj Gen Leland Hobbs |

| 2nd Armored Division | Maj Gen Ernest Harmon |

1 The Wehrmacht defined combat strength as the number of frontline combat troops; it did not include non-combat elements, so, for example, a full-strength infantry division with 14,800 men had a combat strength of 3,800.

2 Of special note is the recent study by Robert S. Rush, Hell in the Hurtgen Forest (University of Kansas, 2001), which takes a detailed look at the experience of one US infantry regiment and its corresponding German opponents in the November 1944 fighting.