Allied planning for the defeat of Germany intended to “rapidly starve Germany of the means to continue the war,” with an emphasis on the capture of the two industrial concentrations in western Germany, the Ruhr and the Saar basin. Of the two, the Ruhr industrial region was the more significant, and the loss of the Ruhr combined with the loss of the Low Countries would eliminate 65 percent of German steel production and 56 percent of its coal production.

Four traditional invasion routes into Germany were considered: the Flanders plains, the Mauberge–Liège–Aachen corridor to the north of the Ardennes, the Ardennes–Eifel, and the Metz–Kaiserlautern gap. The Flanders plains were far from ideal for mechanized warfare due to the numerous rivers and water obstacles. The Ardennes was also ruled out due to the hilly, forested terrain, and its equally forbidding terrain on the German and Luxembourg side, the forested Eifel region in Germany, and the mountainous terrain around Vianden in Luxembourg. Of the two remaining access routes, the Aachen corridor was a traditional invasion route and the most practical. Although the terrain had some significant congestion points due to its high degree of industrialization, it offered the most direct route to the Ruhr. The Kaiserlautern gap was also attractive, especially for access to the Saar; however, its access to the Ruhr was more difficult up along the narrow Rhine Valley. As a result of these assessments, the Aachen corridor was expected to be the preferred route for the Allied advance.

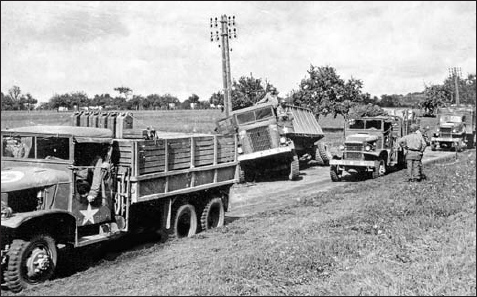

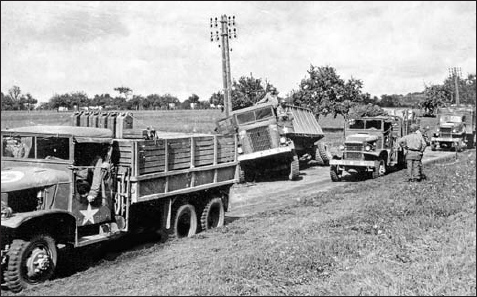

Overextended logistics limited Allied operational goals in the autumn of 1944. Summer expedients like the Red Ball Express truck network were reaching their limit, consuming more fuel than they delivered. Here a Red Ball Express fuel column is seen near Alençon, France on September 2. (NARA).

Original Allied planning assumed that this mission would be undertaken by the British/Canadian 21st Army Group under Gen Bernard L. Montgomery. In the event, this did not occur due to other developments. The V-weapons campaign against Britain in the late summer of 1944 prompted Churchill to urge Eisenhower to push forces further north along the coast to capture German launch sites, and this task fell to the 21st Army Group. Montgomery insisted that Eisenhower cover his flank with at least one US army, and as a result the First Army was directed further north than might otherwise have been the case, leaving Patton’s Third Army the task of assaulting the Metz–Kaiserlautern gap on its own. Although there were expectations that Montgomery’s 21st Army Group would eventually be reoriented away from the Flanders plain and back towards the Aachen corridor, the decision to stage Operation Market Garden in the Netherlands tended to fix this northern orientation.

The failure of Market Garden had several implications for Allied operations in the early autumn of 1944. In the short term, it drained the Allied forces of their limited reserve of supplies and precipitated a temporary logistics crisis. The long-term consequence of the Market Garden operation was that it distorted original Allied strategic planning for the campaign into Germany. The British/Canadian 21st Army Group was now tied down on an axis facing the less desirable Flanders plains, not the Aachen corridor as had been expected. Bradley’s 12th Army Group was bifurcated by the Ardennes, with Hodges’ First Army covering Montgomery’s southern flank whilst being aimed at the Aachen corridor, while Patton’s Third Army was further south in Lorraine aimed along the Metz–Kaiserlautern axis. As a result, the US First and newly arrived Ninth armies fought a campaign completely disconnected from Patton’s operations in the Saar, and the northern element of Bradley’s 12th Army Group now faced the Aachen corridor instead of the anticipated Metz–Kasierlautern axis.

One of Eisenhower’s options was to conduct relatively modest operations along the German frontier until the logistics caught up; this was the option chosen by the Red Army, which had halted operations on its central front in August 1944 to build up for the final offensive into Germany. Eisenhower was not keen on this option, fearing it would permit the Germans to rebuild the Wehrmacht in relative peace, and result in a more formidable opponent when the offensive resumed. Instead, Eisenhower decided to conduct limited offensive operations, which would drain the Wehrmacht by attrition. Some senior US commanders, such as Bradley, believed that it might be possible to reach the Rhine in the autumn, a viewpoint that gradually succumbed to reality in the face of determined German defenses along the Westwall.

The short-term objective in the Wehrmacht in September 1944 was simply to survive after the devastating losses of the month before. This process was greatly aided by two factors: the returning morale of the German troops on reaching German soil, and the halt in the Red Army offensive in Poland. The panic and chaos in the units of Army Group B quickly subsided in mid September. Even if the Westwall was more symbolic than real, there was a sense that the frontier could and should be defended. The halt of the Red Army offensive along the River Vistula in August 1944 also freed up resources for the western front. While fighting continued in the Balkans and in other peripheral theaters, the main front facing central Germany remained quiet until January 1945. The Wehrmacht was living on borrowed time. The loss of Romania’s oilfields in the summer of 1944 doomed the German war effort, since it meant that petroleum would eventually run out. Although large coal reserves kept German industry running, fuel shortages led to a severe curtailment of Luftwaffe operations, cut training of Panzer and aircrews to a minimum, and led to severe restrictions on fuel usage, even in the combat theaters.

For the Wehrmacht, the most immediate mission was to restore the army after the “void” of late August and early September, when defenses in the west seemed to disintegrate. Relieved to have survived the summer battles, these young German soldiers surrendered near Abbeville in early September. (MHI)

The central element in determining the shape of German operational planning in the west was Hitler’s decision in September 1944 to launch a counteroffensive against the Allies sometime in the late autumn or early winter. The plan was dubbed Wacht am Rhein (“Watch on the Rhine”), a deliberate deception to suggest that the forces being mustered for the Ardennes attack were merely being gathered to conduct the eventual defense of the River Rhine. The first draft of the plan was completed on October 11 but it remained a secret to all but the most senior commanders such as Rundstedt and Model, who were briefed on October 22. The plan required that the most capable units, the Panzer, Panzergrenadier and best infantry divisions, be withheld from the autumn fighting and built back up to strength in time for the operation. Holding the River Roer was absolutely essential to the success of the Ardennes offensive, since, if the US Army advanced across the river, they could strike southward against the right flank of the attacking German forces. The challenge to Rundstedt and Model was to hold the River Roer line with an absolute minimum of forces while building up the strategic reserve for the Ardennes operation. This inevitably meant that the defense along the Roer would be conducted mainly by second-rate divisions that could be reinforced with fresher or more capable divisions only under the most dire circumstances. In their favor was the weather and geography. The autumn weather in 1944 was unusually rainy and the resultant mud made mechanized operations along the German frontier extremely difficult. In addition, it substantially suppressed the Allies’ greatest advantage – their tactical air power. Geography aided the defense in two respects. On the one hand, the proximity of the front to German industry and supply dumps simplified German logistics, just as it complicated Allied logistics. On the other hand, the congested industrialized terrain of the Roer, and the mountainous forests of the Hürtgenwald, were well suited to defense.

The Nazi Party tried to assert discipline as the Allied armies approached German soil. This propaganda warning was painted on a wall in Aachen: “The enemy listens!” (NARA)