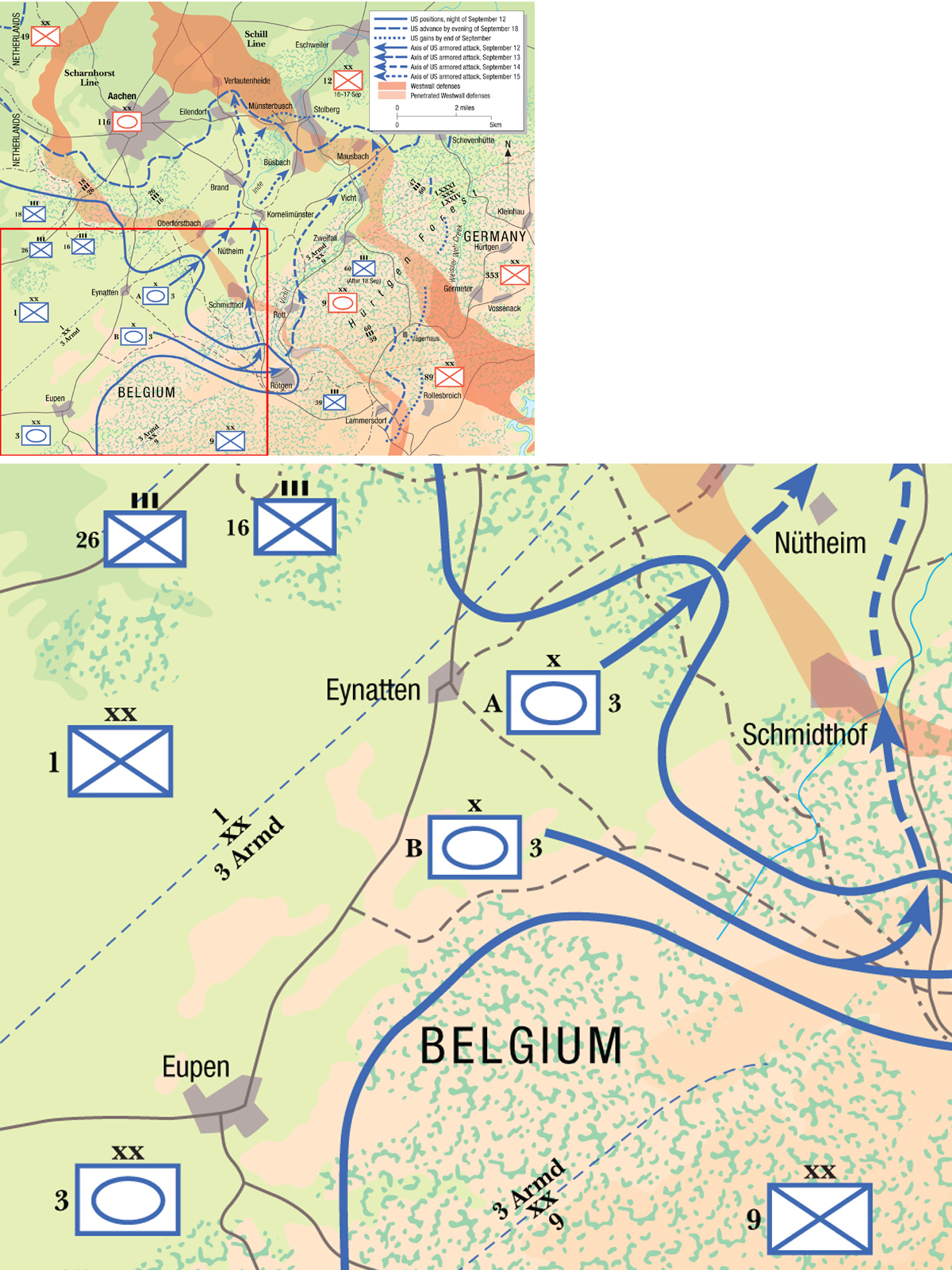

The first US troops to reach German soil were a reconnaissance patrol of the 5th Armored Division, which crossed the River Our near Stalzemburg on the German–Luxembourg border on September 11, 1944. Although the V Corps made several other penetrations, on September 17 Gen Gerow halted any further attacks in this sector, realizing that his forces were too limited to conduct any deep penetration of the defenses in the wooded, mountainous terrain of the Eifel. After a few brief days of fighting, the Ardennes–Eifel front turned quiet, and would remain so for three months until the start of the German Ardennes offensive in this area on December 16.

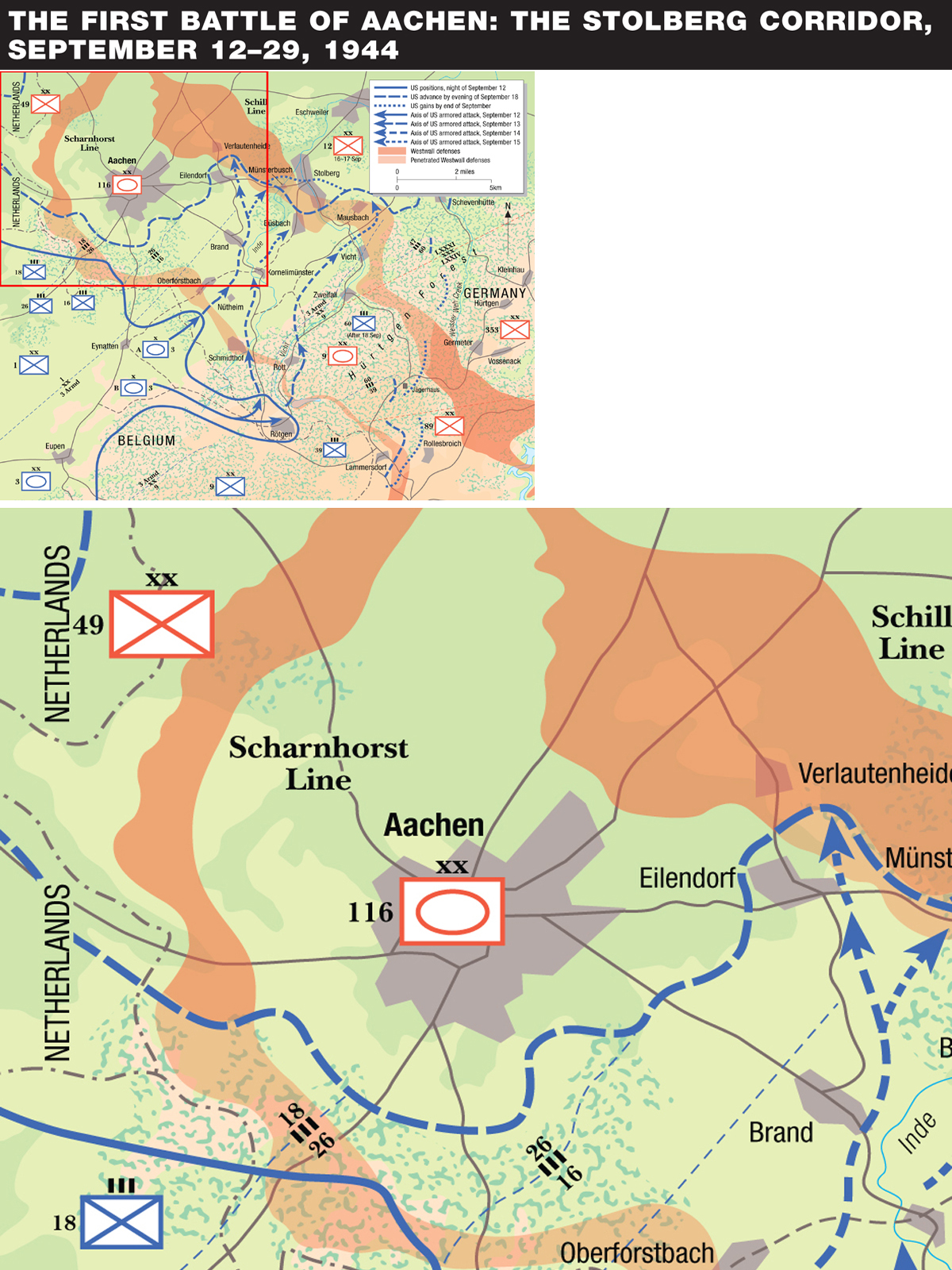

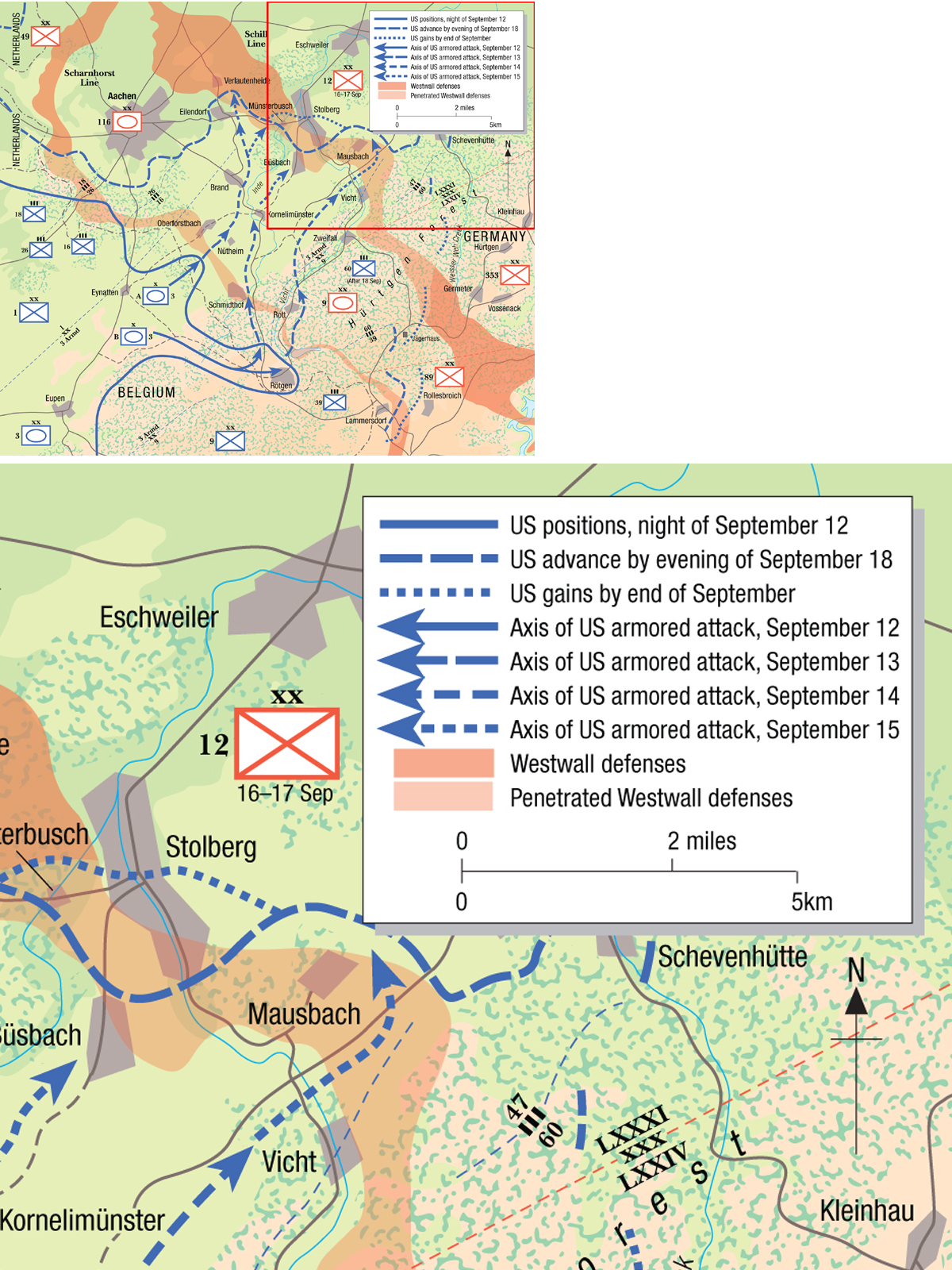

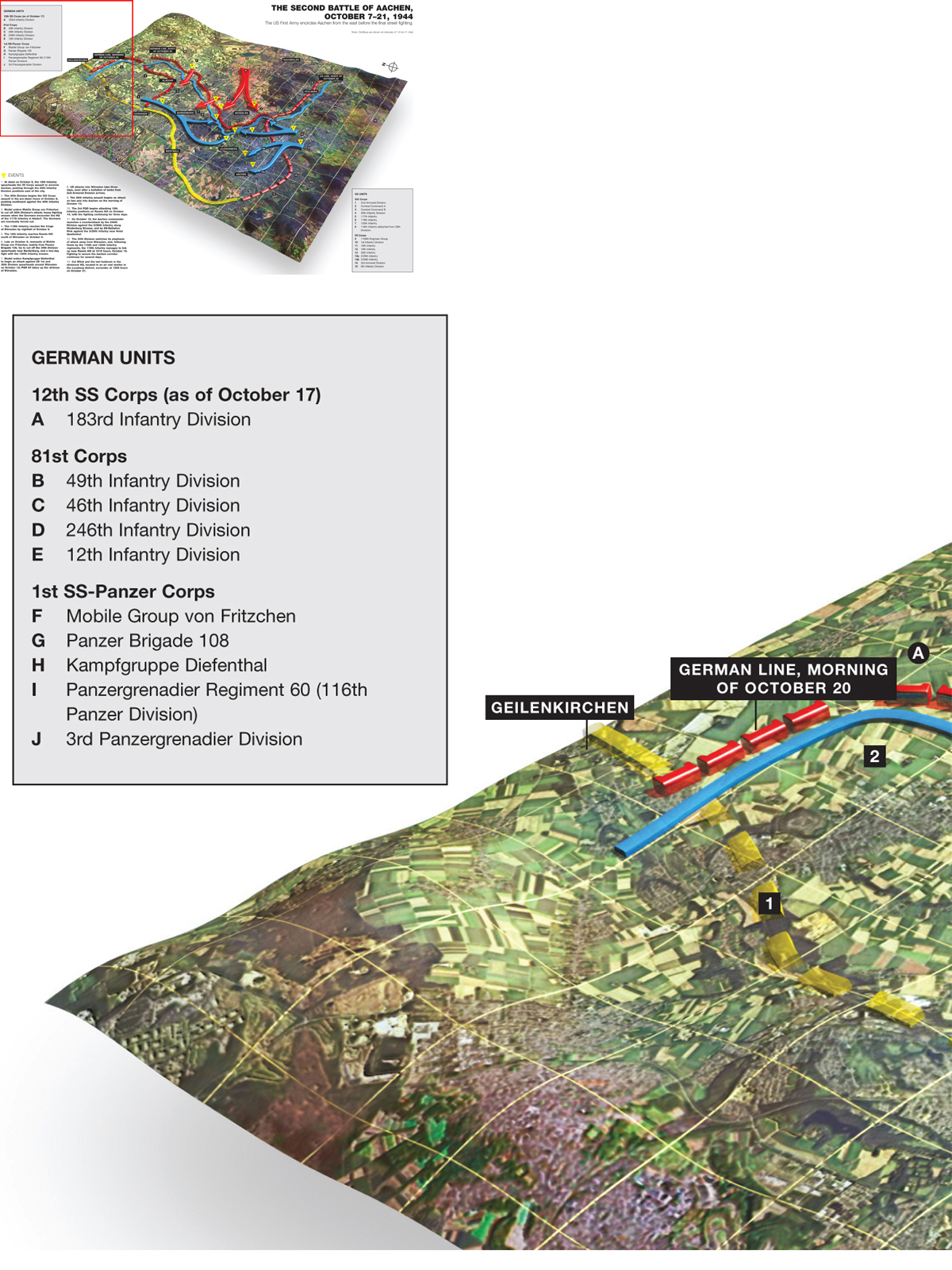

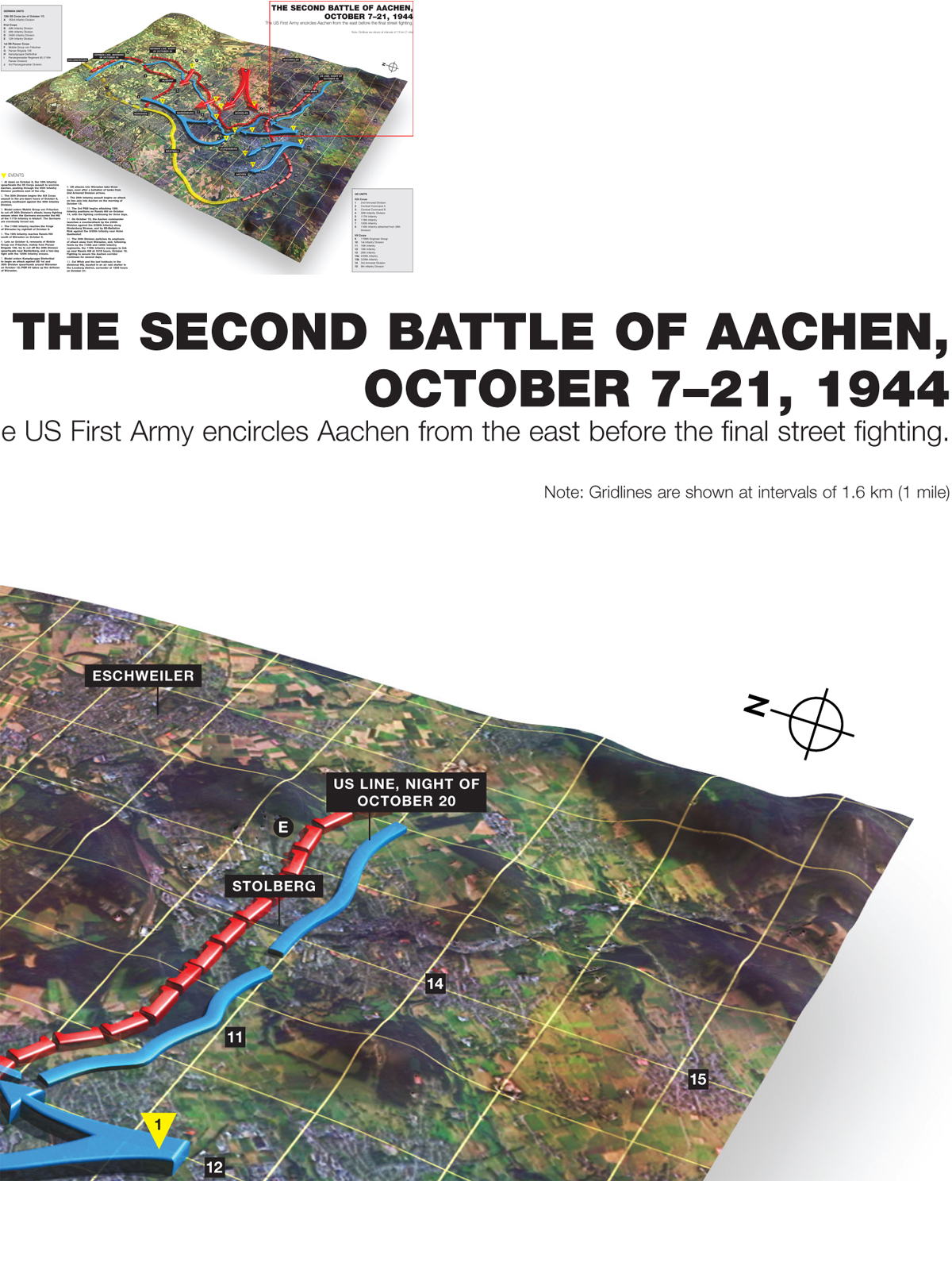

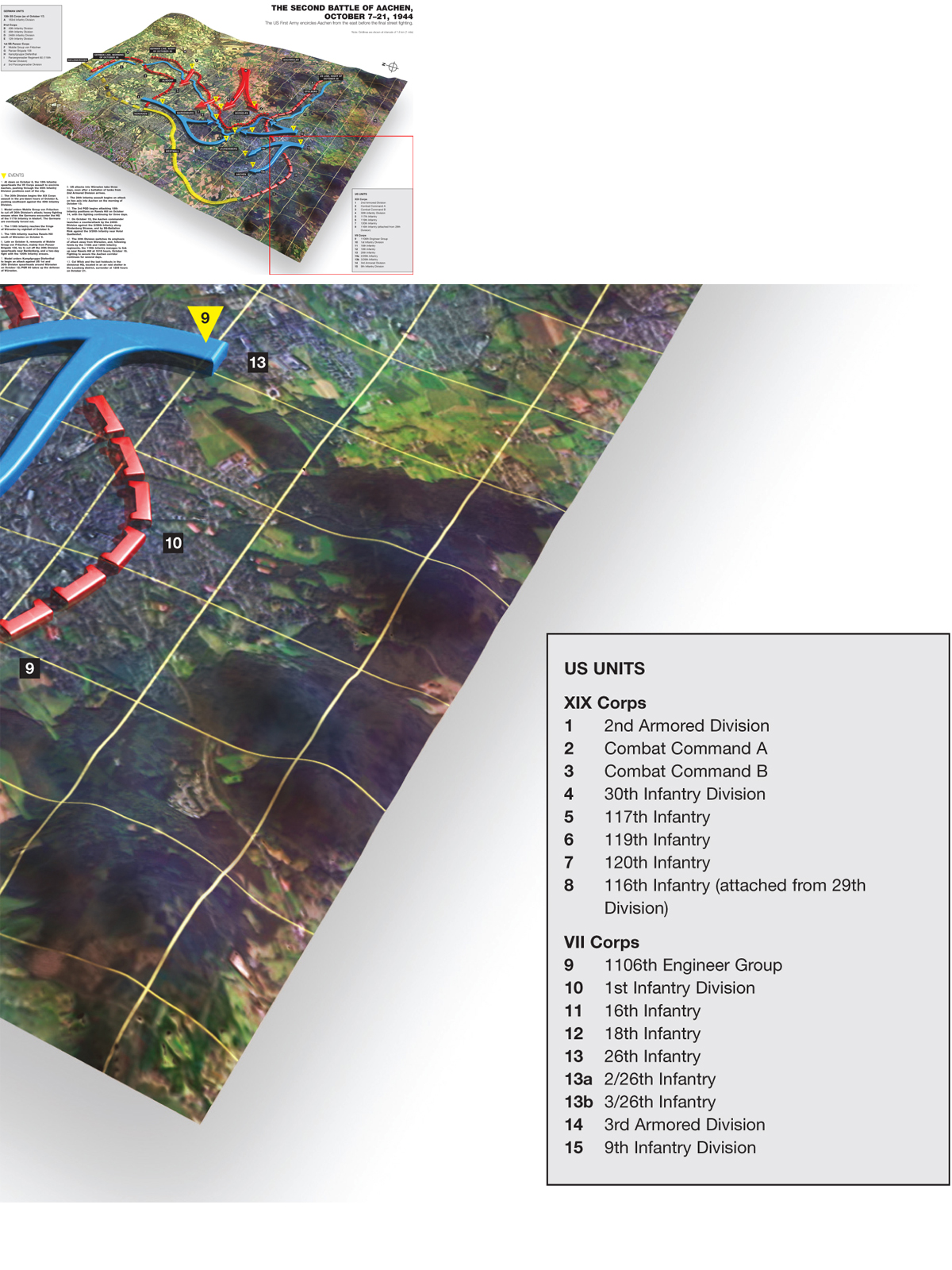

Collins’ VII Corps was moving on a 35-mile-wide front towards the Aachen corridor and began battalion-sized reconnaissance probes against the Scharnhorst Line of the Westwall on September 12. Aachen had been Charlemagne’s capital and the imperial city of the kings of Germania from 936 to 1531; as a result Hitler was adamant that the city be defended. On September 16, Hitler issued a Führer directive. There was no room for strategic maneuver now that the enemy had reached German soil: every man was to “stand fast or die at his post.” To facilitate the defense, Hitler ordered the civilians evacuated and by mid September, the population had fallen from 165,000 to about 20,000. The German 81st Corps assumed that the main US objective would be the city, and so assigned the defense to its best unit, the 116th Panzer Division, which began arriving on September 12.

Engineers of the 3rd Armored Division plant demolition charges on dragon’s teeth along the Scharnhorst Line in September, trying to blast another corridor towards Aachen. (NARA)

GIs of the 39th Infantry, 9th Infantry Division, riding on supporting M4 tanks of the 746th Tank Battalion, pass through the line of dragon’s teeth of the Scharnhorst Line during the advance on Lammersdorf on September 15. (NARA)

In fact, the main objective of the VII Corps was to push up the Stolberg corridor with the aim of reaching the River Roer. The Combat Command B (CCB) of the 3rd Armored Division began moving forward at dawn on September 13, gradually battering its way up the Stolberg corridor. Closest to the city, the 16th Infantry stalled along the Westwall in the Aachen municipal forest. The penetrations accelerated over the next few days. The 1st Infantry Division pushed through the bunkers in the Aachen municipal forest, with two of its regiments reaching the southern outskirts of the city, while the 16th Infantry furthest east reached Ellendorf at the edge of the Schill Line. CCA of the 3rd Armored Division had the most dramatic gains, pushing all the way to the southern edge of Eilendorf to await infantry reinforcements. CCB of the 3rd Armored Division pushed northward out of the Monschau forest advancing with one task force into Kornelimunster and the other to the outskirts of Vicht. German resistance varied considerably; some of the Landesschütz territorial defense battalions evaporated on contact, while small rearguards from regular army units fought tenaciously. On September 15, both combat commands of the 3rd Armored Division penetrated into the Schill Line, with CCA coming under determined fire from StuG III assault guns holding the high ground near Geisberg, while the CCB’s lead task force was stopped by tank fire from Hill 238 west of Gressenich. The 9th Panzer Division claimed the destruction of 42 US tanks that day – an exaggeration, but also a clear indication of the intensity of the fighting.

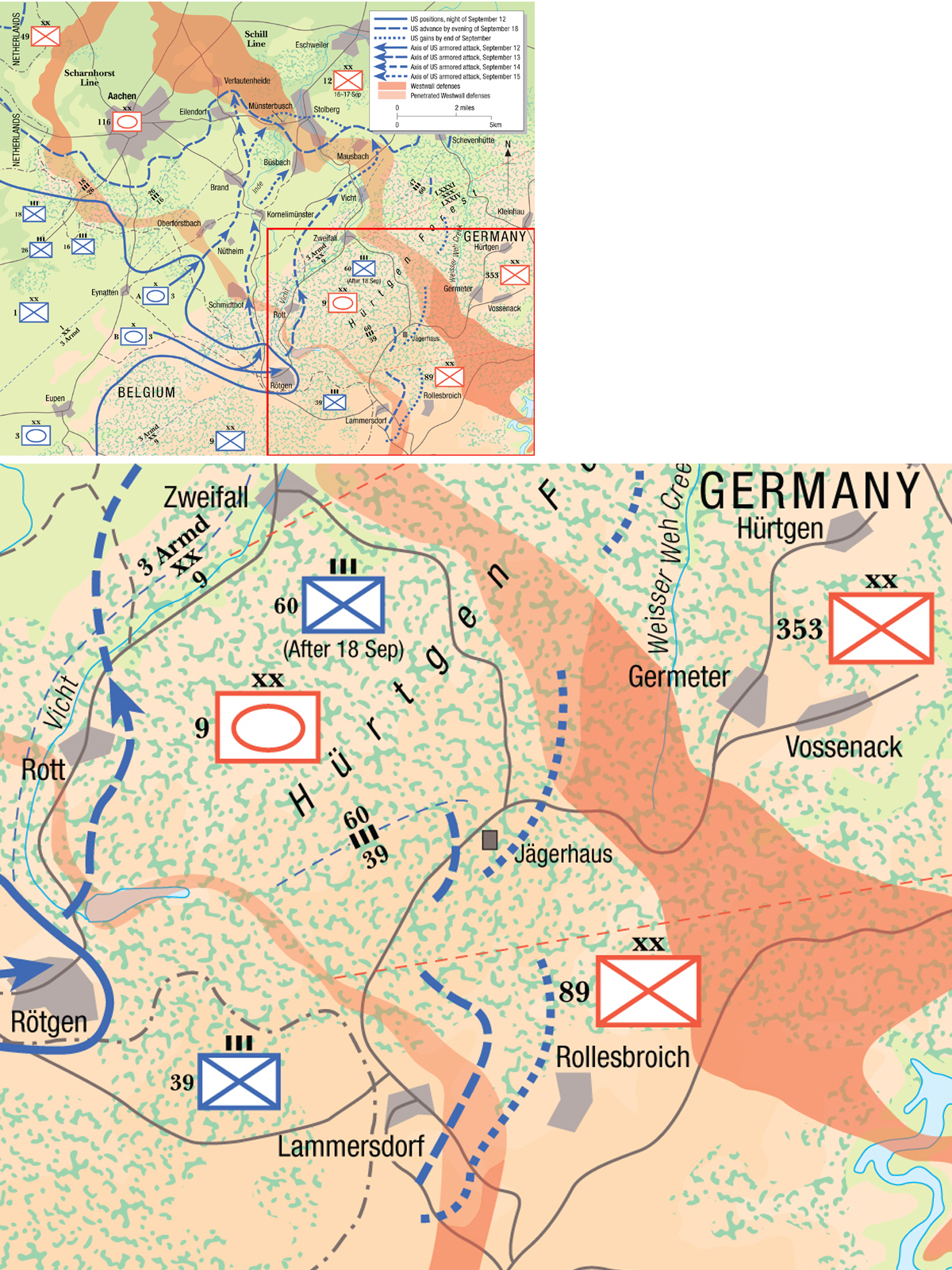

With the attack up the Stolberg corridor proceeding well, the 9th Infantry Division began a methodical advance into the Hürtgen forest on the right flank of the 3rd Armored Division, moving through both the Scharnhorst and Schill lines as far north as Schevenhütte. The attempt to clear the Hürtgen forest gradually ground to a halt after encountering elements of the 89th Infantry Division in bunkers of the Schill Line. Even though the German defenders were outnumbered, the well-placed bunkers considerably amplified their combat effectiveness. The determined defense by the regular infantry was a complete contrast to earlier fighting against the initial Scharnhorst Line where local territorial defense units were not so resolute.

One tactic for dealing with Westwall bunkers was to blow open the rear door with a bazooka, as demonstrated by this team from the 24th Cavalry Reconaissance Squadron of the 4th Cavalry Group. (NARA)

The 9th Infantry Division reached Schevenhütte before being counterattacked by the newly arrived German 12th Infantry Division on September 17. A task force of the 3rd Armored Division intervened, and a pair of their M4A1 (76mm) tanks are seen in front of St Josef church on September 22. (NARA)

By now Gen Schack of the 81st Corps realized that the main US goal was to push through the Stolberg corridor, but the presence of the 1st Infantry Division on the doorstep of Aachen and the constant American shelling of the city suggested that the capture of the city was also an American objective. As a result, he kept Schwerin’s 116th Panzer Division defending the city instead of attacking the flank of the American assault. The momentum of the battle shifted on September 17 following the arrival of the 12th VGD. This fresh, full-strength division had been allotted by Hitler to ensure the defense of Aachen, and was commanded by one of Hitler’s former military adjutants, Col Engel. Although Schack attempted to keep it intact for a decisive action, he was forced to commit it piecemeal, and an initial Fusilier Regiment 27 counterattack was beaten back with heavy losses. The arrival of these critical reinforcements permitted counterattacks all along the American lines, including determined attacks against the US 9th Infantry Division near Schevenhütte by Grenadier Regiment (GR) 48. With his own troops overextended and short of ammunition, Collins ordered his troops to consolidate their positions on the evening of September 17, except for the 9th Infantry Division still fighting in the Hürtgen. Skirmishes continued over the next few days with little movement as both sides tried to wrest control of key geographic features, such as the hills around Stolberg, and the towns of Verlautenheide and Schevenhütte. The Wehrmacht succeeded in halting the advance, but at a heavy cost in infantry. The newly arrived 12th VGD dropped in combat strength from 3,800 to 1,900 riflemen, and the 9th Panzer Division and its attachments lost over a thousand men, equivalent to about two-thirds of their combat strength compared to a week earlier.

Collins hoped that the 9th Infantry Division could push southeast out of the Hürtgen forest and seize the towns in the clearing on the road to Düren. With the fighting along the Stolberg corridor stalemated, the continuing US advance in the woods attracted the attention of the Seventh Army commander, Gen Brandenberger, who scraped up a few assault guns to reinforce the patchwork 353rd Infantry Division holding these towns. Both sides were badly overextended and exhausted, and small advantages could have a disproportionate effect. After repeated attempts, the 9th Infantry Division’s push east through the wooded hills was halted short of the Hürtgen-Kleinhau clearings, ending the first attempt to clear the Hürtgen forest.

While most of the fighting by the US First Army had been concentrated in the VII Corps sector, Corlett’s XIX Corps had taken advantage of the weak German defenses in the southern Netherlands to push up to the Westwall. In spite of the severe fuel shortages, the 2nd Armored Division pushed beyond the Albert Canal to Geilenkirchen, while on its right flank the 30th Division pushed towards Rimburg, an advance of some 15 to 33 miles in ten days. Nevertheless, German resistance was continuing to harden, and the XIX Corps was unable to intervene in the fighting around Aachen as a result.

With the launch of Operation Market Garden further north in the Netherlands by the 21st Army Group on September 17, US operations against the Westwall came to a halt for the rest of September. Low on supplies, out of fuel, overextended by the vagaries of the summer advance, and now facing a much more vigorous defense, it was time to recuperate and take stock. On September 22, Gen Hodges made this official, with instructions to shut down the remaining offensive operations in the VII Corps and XIX Corps sectors. During the final week of September, the US forces in the Aachen sector reorganized with the arrival of the Ninth Army. The new army was wedged between the British 21st Army Group to the north in the Netherlands, and the US First Army around Aachen.

To push to the River Roer, XIX Corps needed to breach the Westwall north of Aachen to come in line with VII Corps. By now, the Wehrmacht was alerted to the threat, and Gen Corlett expected the defenses to be fully prepared, unlike the situation in September. As a result, an effort was made to breach the Scharnhorst Line more methodically. In preparation, the XIX Corps artillery set about trying to eliminate as many bunkers as possible. It was evident from captured bunkers that the divisional 105mm and 155mm howitzers were not powerful enough to penetrate them. Fortunately, the US Army-ETO earlier in 1944 had anticipated the need for special weapons to deal with the Siegfried Line and had requested the dispatch of about seventy-five M12 155mm gun motor carriages to France. These were old World War I French 155mm GPF guns mounted on an M4 tank chassis, and they made formidable bunker-busters. The XIX Corps began a concerted campaign to bombard the German bunkers with divisional artillery to damage nearby field entrenchments and strip away camouflage from the bunkers. The M12 155mm GMC were then moved up close to the front under the cover of darkness, and set about attacking the bunkers from a few hundred yards away.

Once the 30th Division had penetrated the Westwall near Palenberg, the 2nd Armored Division exploited the breach and pushed on through Ubach. Here, an M4 tank of the 3/67th Armored takes up defensive positions outside the town on October 10. Having fought through the Siegfried Line, the front turned into a stalemate by early October.

While the artillery preparations were under way, the infantry from the 30th Division was being trained in bunker-busting tactics. Two specialized weapons were issued: man-portable flamethrowers, and demolition charges mounted on poles to attack the vulnerable embrasures. Supporting tank units were also trained in bunker tactics, with some tanks being fitted with flamethrowers in place of the hull machine gun.

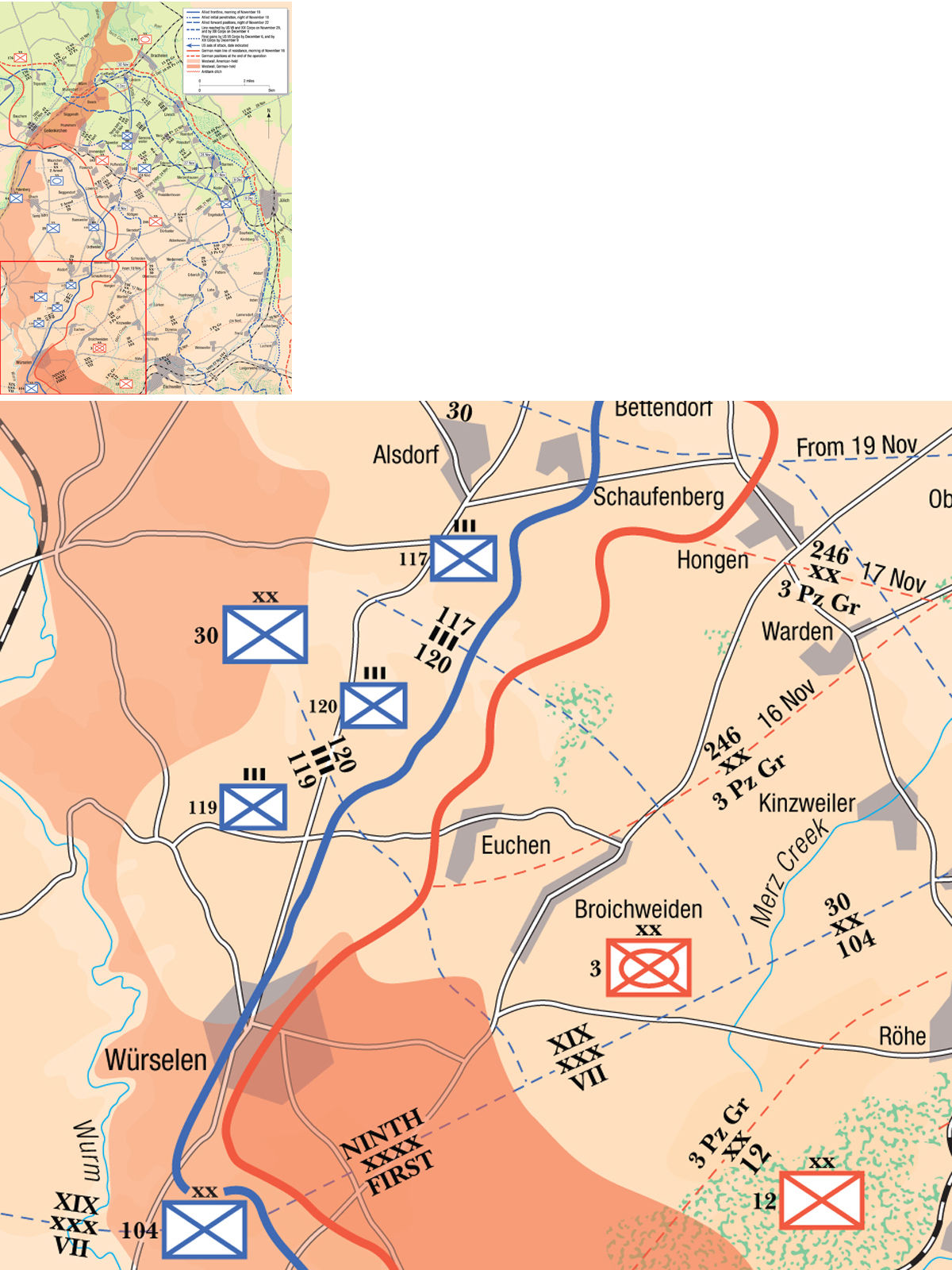

The attack by two regiments of the 30th Division against Rimburg–Palenberg was accompanied by feints further north and south to confuse the Germans as to the actual focal point. In the event, the new German 81st Corps commander, Gen Köchling, mistakenly believed that the renewed American offensive would again take place in the Stolberg corridor, and he viewed the preparations north of Aachen as a feint. The XIX Corps attack was preceded by a major air attack by medium bombers of the Ninth Air Force, but the October 2 bombing had little effect on German fortifications already ravaged by artillery over the past week. The first obstacle facing the 117th and 119th Infantry was the River Wurm, but they found that it was far less formidable than feared.

In the 117th Infantry sector, the new bunker-busting tactics proved very effective. Once artillery fire lifted, the embrasures were kept under machine-gun and bazooka fire while the infantry with pole-charges and flamethrowers advanced into range. The flamethrowers kept the pillboxes suppressed while the pole-charges were put into place against the embrasures or doors. Palenberg and Marienberg were captured by the end of the day, but the 119th Infantry was stalled by a disguised bunker reinforced by strongpoints near the medieval Rimburg castle. The next day, the 117th Infantry pushed into Ubach, but the 119th Infantry again became stalled after encircling and clearing the Rimburg castle. The capture of Ubach prompted Gen Corlett to commit a combat command of the 2nd Armored Division into the bridgehead earlier than expected in spite of the congestion.

The scale of the fighting on October 3 made it clear to Köchling that the focus of the attack was in the Palenberg–Rimburg sector, but reinforcements were slow in arriving and the planned counteroffensive in the early morning hours of October 4 fizzled out. The main attack emerged at dawn and managed to push back one US infantry company of the 119th Infantry before German artillery accidentally hit its own advancing troops, disrupting the attack. A third attack later in the day against Ubach ran into a planned attack by a task force of CCB, 2nd Armored Division, and the German infantry battalion was badly mauled. The other task force set out in the late afternoon under heavy German artillery fire, but once it exited Ubach, it picked up momentum. The locations of the German bunkers were well known, and coordinated tank-infantry attacks cleared them out. By nightfall, CCB had made some significant advances, though at a heavy cost in infantry and tanks. The American attacks had proven so worrisome that both Rundstedt and Brandenberger personally visited the 81st Corps headquarters and pledged to send Köchling as many reinforcements as they could muster to stamp out the American bridgehead.

In reality, German resources were stretched thin, and the reinforcements from the Seventh Army were the usual mishmash: NCO training school battalions from Düren and Jülich, a single battalion from the 275th Division, a fortress machine-gun battalion, and elements of an artillery brigade. Köchling himself was able to rearrange his corps in order to squeeze out a few more battalions for a counterattack. The October 5 counterattack was delayed by the usual problems of moving the troops into place, and many of the reinforcements were committed piecemeal to resist the renewed US attacks. German artillery fire proved to be unusually heavy, as Köchling had managed to shift more and more batteries into the threatened sector. By this stage, the German artillery included two railroad guns, a heavy howitzer battalion, forty-seven 150mm gun-howitzers, forty 105mm howitzers, thirty-two 88mm guns, and a variety of small-caliber weapons. The counterattack finally began on October 6 but was a pale shadow of the intended attack and the five assault-gun formations had been reduced to 27 vehicles. The American front exploded on October 7 when CCA, 2nd Armored Division moved into the breach. The 117th Infantry, with the support of the 743rd Tank Battalion, overran the German 49th Division, which by that stage had been reduced to a single infantry regiment. The advance put the 30th Division in Alsdorf, to the northeast of Aachen.

Troops of the 172nd Engineer Combat Battalion inspect German prisoners on October 6, following the capture of Ubach by the 2nd Armored Division. (NARA)

AACHEN STREET FIGHTING, OCTOBER 15, 1944 (pages 38–39)

In preparation for the attack into the center of Aachen, the 2/26th Infantry received specialized urban assault training developed on the spot by its commander, Lt Col Derrill Daniel. Short of manpower, Daniel was intent on substituting firepower for manpower and he dubbed the tactics as “knock’em all down.” Each rifle company was organized as a task force with an attachment of three M4 medium tanks (1) or M10 tank destroyers (2), two 57mm antitank guns, two bazooka teams, a flamethrower, and two heavy machine-gun teams. To ensure that ammunition continued to flow in and casualties flowed out in a timely fashion, Daniel obtained M29 Weasel cargo carriers to deal with the rubble-filled streets. The tactics were to use firepower to chase the defenders into the cellars, at which point they would be attacked with grenades and flamethrowers. The attack was staged to systematically rout out the German defenders a street at a time, as seen here. The infantry would move along the sides of the street, using the buildings for cover, while the tanks and tank destroyers would move forward to provide direct firepower support. Co-ordination was essential, and the German infantry was armed with the potent Panzerfaust antitank rocket. The task of the US infantry was to keep the German infantry at bay, so that they could not use the short-range Panzerfaust effectively. At least one M12 155mm GMC was used during the city fighting to knock out especially stubborn resistance points. Its 155mm gun could often bring down an entire building with only a few high-explosive rounds. By the time of the October 1944 fighting, the city had already been devastated by previous bombing and shelling. However, the streets were relatively clear of rubble, as the city government had attempted to keep main thoroughfares open until the evacuation on October 12. German defenses were based in the ruined housing and buildings, which offered a measure of protection against small-arms fire. However, the entire city garrison comprised only about 5,000 troops, and included a large number of Luftwaffe and naval personnel hastily transferred to the army in September with little or no infantry training. As a result, the two US attack battalions, although significantly outnumbered, were able to steadily advance and capture the city in less than a week.

In less than a week, XIX Corps had punched a considerable hole in the Westwall north of Aachen and threatened to link up with VII Corps somewhere north of Stolberg. Kochling’s 81st Corps at the time had four understrength divisions including the 49th and 183rd divisions that had been battered in the Palenberg–Rimburg fighting. The 246th VGD replaced the 116th Panzer Division in Aachen to permit its refitting, and the 12th Infantry Division was still in position southeast of Aachen to block any further advances by VII Corps. The effective combat strength of these four divisions was in the order of 18,000 infantry. Although German effective strength had fallen due to the fighting, its artillery had continued to increase and totaled 239 weapons, including one hundred and forty 105mm, eighty-four 150mm, and 15 heavy guns. Armored support was very weak compared with American strength, with only 12 serviceable StuG III assault guns; schwere Panzer Abteilung (s.Pz.Abt.) 508 had four Kingtiger tanks and Panzer Brigade 106 was down to seven Panthers. The Panzer units that had played such a central role in the fighting for the Stolberg corridor – the 9th and 116th Panzer Divisions and Panzer Brigade 105 – were refitting. To preempt the link-up of the American XIX and VII Corps, Model proposed launching a strong counteroffensive using the partly reequipped 116th Panzer Division and 3rd Panzergrenadier Division (PGD) through the open terrain northeast of Aachen towards Jülich.

On October 8, Mobile Regiment von Fritzchen attempted to push the 30th Division out of Alsdorf. Here the 117th Infantry has established an antitank defense in the streets of neighboring Schauffenburg using an M5 3in. antitank gun of the attached 823rd Tank Destroyer Battalion, along with a bazooka team and a .50-cal heavy machine gun. (NARA)

While Aachen was being encircled, 9th Division remained engaged in its efforts to push through the Hürtgen forest. Here, a 105mm M3 howitzer from a regimental cannon company is seen providing fire support on October 8.

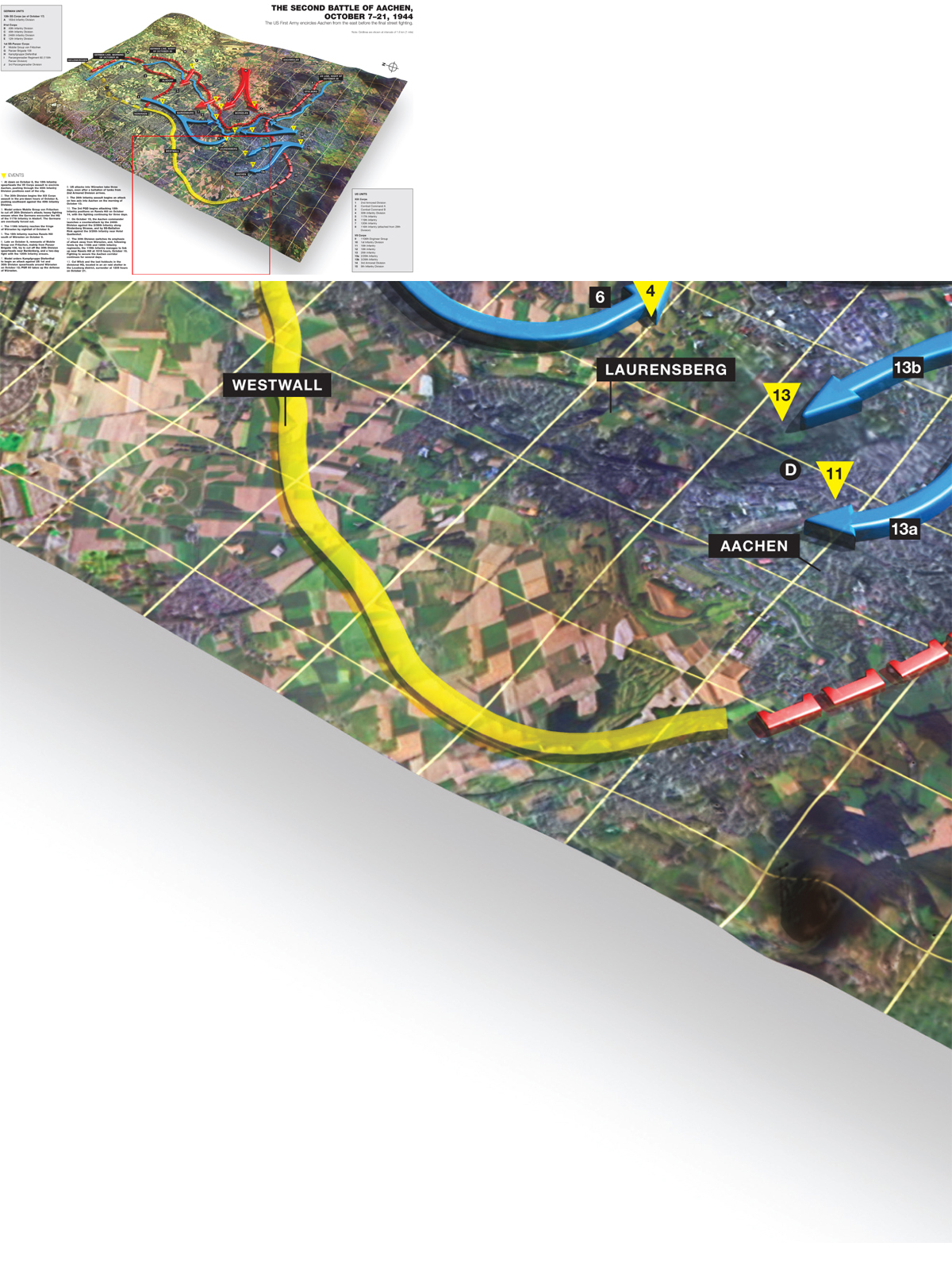

The US First Army planned to close the gap around Aachen using the overstretched 1st Infantry Division. The division was already deployed in a cordon defense around the southern edges of Aachen with only one regiment free for the assault, the 18th Infantry. The attack started in predawn hours of October 8, using combined tank-infantry tactics to bust open the bunkers in the Schill Line defenses. The initial objectives were a series of hills with commanding views of the area north of the city at Verlautenheide, Crucifix Hill and Ravels Hill. All three were captured by October 10. The main impediment to the American attack was the intense German artillery fire.

The XIX Corps attack from the north was conducted by the 30th Division aimed at Würselen. Against this advance, Model committed Mobile Regiment von Fritzchen – slapped together from three infantry battalions, and supported by 11 tanks of Panzer Brigade 108, a few Kingtigers from s.Pz.Abt 506 and 22 StuG III assault guns from three assault gun battalions. This battlegroup was ordered to clear Alsdorf of the 30th Division as a means of keeping open the corridor to Aachen. The initial advance by the 30th Division on October 8 went smoothly, but in mid morning the lead elements of 117th Infantry were struck on their eastern flank by elements of Mobile Regiment von Fritzchen from Mariadorf. This was only a part of the German attack, the other force attacking Alsdorf directly. The attack on Alsdorf found the town occupied by headquarters elements of the 117th Infantry, who set up a hasty defense. They were soon supported by some tanks of the 743rd Tank Battalion, which knocked out the four Panzers supporting the German infantry and helped to break the back of the attack. Although both attacks by Mobile Regiment von Fritzchen were beaten off with heavy German casualties, the 30th Division attack towards Würselen was halted for the day.

Mobile Regiment von Fritzchen was then shifted into the gap between the US 30th and 1st Infantry divisions in an attempt to prevent the link up. However, the German attacks on October 9 were frustrated by corresponding US attacks, and the 119th Infantry managed to push into northern Würselen by nightfall, only 2,000 yards from the 18th Infantry positions on Ravels Hill. This spearhead was hit that night by an attack of 300 infantry and five tanks from Panzer Brigade 108 around Bardenburg, which threatened the 30th Division advance. The capture of Birk the following morning by the 120th Infantry trapped the German force, but a fruitless day of fighting ensued with heavy casualties on both sides. On October 11, the 30th Division sent in its reserve, a single battalion of the 102nd Infantry, to finally wrest control of the town after it had been pummeled by artillery. Panzer Brigade 108’s defenses had been stiffened by a battalion of half-tracks with quad 20mm antiaircraft guns, but all six Panzers and 16 half-tracks were knocked out or captured, most falling victim to close-range bazooka attack.

The next elements of Model’s counterattack force, arriving on October 11, included Kampfgruppe Diefenthal, which had been scraped together from survivors of the 1st and 12th SS-Panzer divisions, as well as Panzergrenadier Regiment (PGR) 60 of the 116th Panzer Division. In view of the gravity of the situation around Würselen, Model authorized Brandenberger to use the units as they became available instead of waiting for the whole force to arrive. As a result, the outlying positions of the 30th Division were hit by a succession of German attacks on October 12, heavily supported by Panzers. After days of overcast conditions, the weather that day was crystal clear, allowing Allied air power to intervene. The final push was reinforced by two battalions from the 116th Infantry, 29th Division, a battalion of tanks from the 2nd Armored Division, and an engineer battalion staging a direct frontal assault through the streets of Würselen. The attack was very slow going, since the town was occupied by the entire PGR 60, supported by dug-in Panzers, and little progress was made in three days of fighting.

Having already committed bits of the arriving 116th Panzer Division, Brandenberger received permission from Model to commit the 3rd PGD against the other wing of the American advance, the 18th Infantry positions on the hills around Verlautenheide. On the morning of October 14, PGR 29 supported by Kingtigers and captured M4 tanks of s.Pz.Abt. 506 attacked, but the opposing VII Corps artillery was waiting. When the attack formed up in the meadows in front of the US positions, it was hit by fire from six US artillery battalions, leading the divisional commander, Gen Maj Walter Dekert, to conclude that “it was obvious that an advance through this fire was impossible.” The artillery stripped away the Panzergrenadiers, but a few Kingtiger tanks ploughed into the American lines and began shooting up the forward trenches. Panzergrenadier Regiment 8 tried to attack later, but was pummeled by artillery and subsequently strafed by a squadron of P-47 fighter-bombers. The violent attacks finally petered out by evening, with the US infantry still in control of their defenses. The 3rd PGD returned to the attack in the pre-dawn hours of October 15, nearly overrunning an infantry company in the dark. The US infantry huddled in their foxholes while US mortar fire and artillery landed nearly on top of them. As dawn arrived, the German survivors retreated into the early morning haze. Fighting continued over the next few days, but on a much smaller scale. The 1st Division suffered 540 casualties in the three days of fighting, but the 3rd PGD lost a third of its effective strength.

With the German counteroffensive petering out, Hodges put more and more pressure on the 30th Division to finish the task by sealing the gap with the 1st Division. Since Würselen had proven impossible to take, Hobbs redirected the focus of the October 16 attack by the 119th Infantry west through Kohlscheid, while diversionary attacks were staged further east by the 117th and 120th Infantry. The diversions were costly, but managed to distract German artillery enough for the 2/119th Infantry to finally reach Hill 194 by late afternoon, within a thousand yards of the 1st Division positions. At 1615 hours, patrols from both divisions linked up near Ravels Hill, finally closing the Aachen gap.

On October 10, the US Army sent a delegation into Aachen with a surrender ultimatum; based on Hitler’s orders, it was rejected. Defending Aachen under the command of Col Gerhard Wilck was the 246th Division, which had three infantry battalions, two fortress battalions, some Luftwaffe troops, and about 125 city policemen. While understrength, Wilck’s force actually outnumbered the attacking US infantry force about three to one. The 1st Infantry Division was so tied down defending the northern salient against attack that only two battalions of the 26th Infantry could be spared to assault the city center. The 2/26th Infantry was assigned the task of clearing the center of the old city while 3/26th Infantry took on the northern sector, which had a mixture of industrial, park and urban areas.

The reduction of the city began on October 11–12 with artillery and air attacks. The 1106th Engineer Group attempted to demolish buildings near the outskirts by filling trolley cars with captured explosives and then rolling them into the city. Although three of these “V-13’s” were launched, they had little effect. The infantry assault began on the morning of October 13. Both battalions methodically pushed forward, clearing the area of both troops and a large number of German civilians still trapped in the basements. During the fighting, SS-Battalion “Rink” was sent into Aachen to reinforce the 246th Division, and Wilck assigned it the task of stopping the 3/26th Infantry advance. On October 15, 2/26th Infantry linked up with 3/26th Infantry and managed to secure a massive above-ground air-raid shelter that was housing about 200 soldiers and 1,000 civilians. With the two American columns closing in on the divisional headquarters at Hotel Quellenhof, Wilck ordered a counterattack on the afternoon of October 15. The fighting along Hindenberg Strasse started around dusk, and, after about two hours of fighting the 2/26th Infantry, the German infantry battalion was repulsed with significant casualties on both sides. As 3/26th Infantry approached the hotel, SS-Battalion Rink attacked and drove the US infantry back. After a two-day lull, the US attack resumed on October 18; they regained the lost ground, and assaulted Hotel Quellenhof. To conduct this final clearing operation, 3/26th Infantry was reinforced by Task Force Hogan from the 3rd Armored Division with an armored infantry battalion and parts of a tank battalion. Task Force Hogan attacked Lousberg from the west while 3/26th attacked through Salvatorberg from the east, both prongs meeting around noon on October 19. The last hold-outs were ensconced near the divisional HQ in an air-raid shelter in Lousberg, where they were trapped by the 2/26th Infantry. An M12 155mm GMC was driven up to the site to blast it open, but Col Wilck surrendered moments before. The surrender of the garrison officially took place at 1205 hours on October 21. About 1,600 German troops surrendered at the end, bringing the total number of German prisoners of war to 3,473 out of the original garrison of about 5,000. In addition, US troops evacuated about 6,000 civilians during the course of the fighting, and a further 1,000 after the surrender.

The tactics of the 26th Infantry during the Aachen street fighting was to use firepower to reduce German defenses. Here, infantrymen of 2/26th Infantry look on while an M4 medium tank of the 745th Tank Battalion blasts away on October 15. (NARA)

A 57mm antitank gun fires on German defenses during the advance by Company E, 2/26th Infantry on October 15 in Aachen. (NARA)

German prisoners are escorted out of the city center by troops of the 2/26th Infantry on October 15. (NARA)

Col Gerhard Wilck, commander of the 275th Infantry Division responsible for the defense of Aachen, is seen here with his staff following the surrender on October 21. (NARA)

Kampfgruppe Rink from SS-PGR 1 attempted to evacuate their wounded out of Aachen on October 20 using their surviving SdKfz 251 half-tracks, but were captured by a US tank roadblock on Oststrasse in Kohlscheid. (NARA)

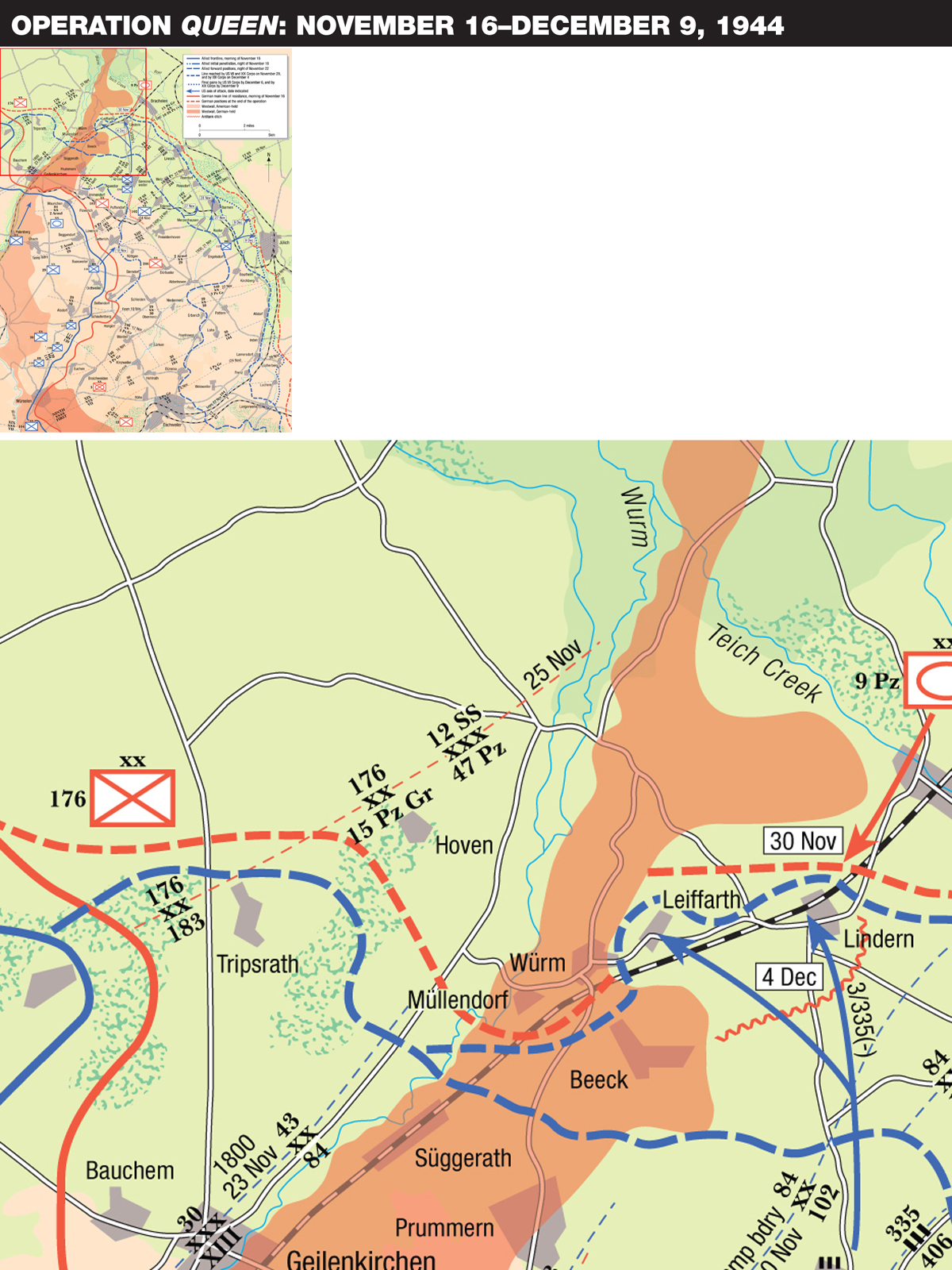

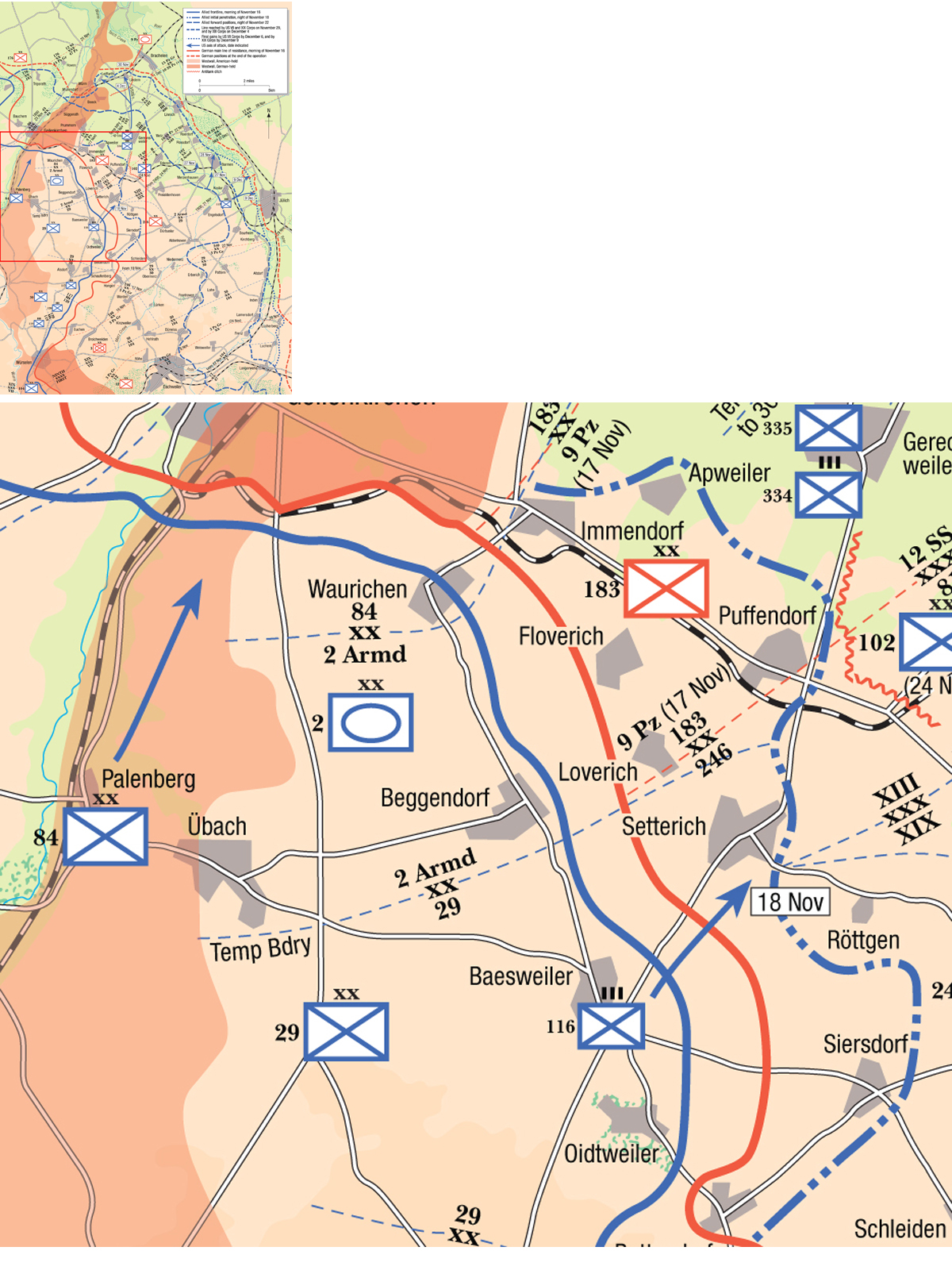

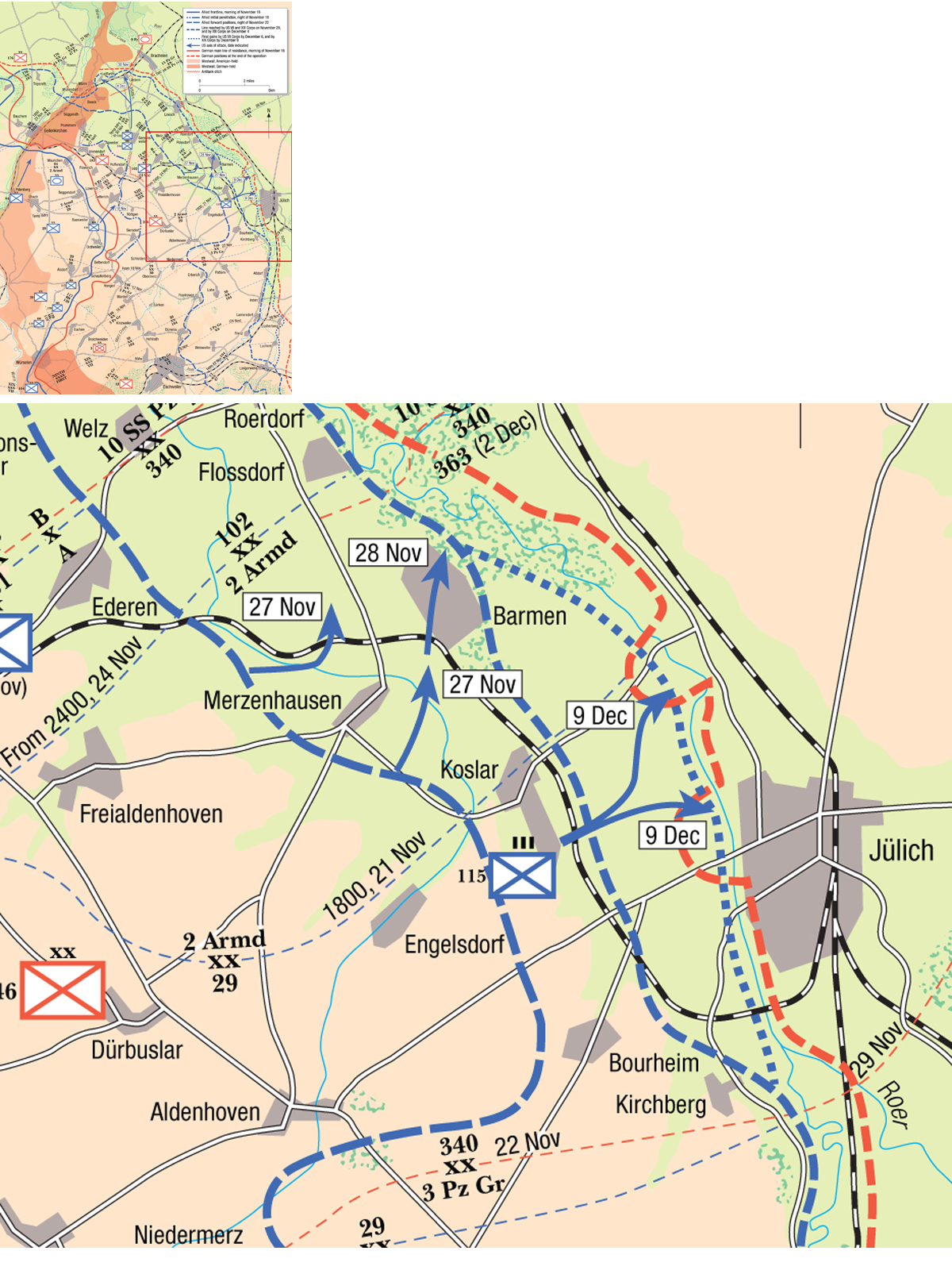

The capture of Aachen consolidated the US First and Ninth armies’ positions, and set the stage for an offensive to reach the River Rhine. On October 18, 1944, Bradley and Montgomery met Eisenhower at his headquarters to discuss plans for November. In spite of shortages of supplies and infantry, Eisenhower was insistent that the Germans enjoy no respite from Allied attack and laid out a plan for a broad-front attack in November aimed at bringing the Allied forces up to the Roer in anticipation of a subsequent push to the Rhine. For Bradley’s 12th Army Group, the plan was to employ all three armies in a concerted attack with the final objective being a bridgehead over the Rhine south of Cologne. Hodges’ First Army was scheduled to launch its attack, Operation Queen, on November 5, with the focus being in the center with Collins’ VII Corps.

Into the “Death Factory.” A squad from Company E, 2/110th Infantry, 28th Division begins moving into the Hürtgenwald on the first day of the attack, November 2, 1944. (NARA)

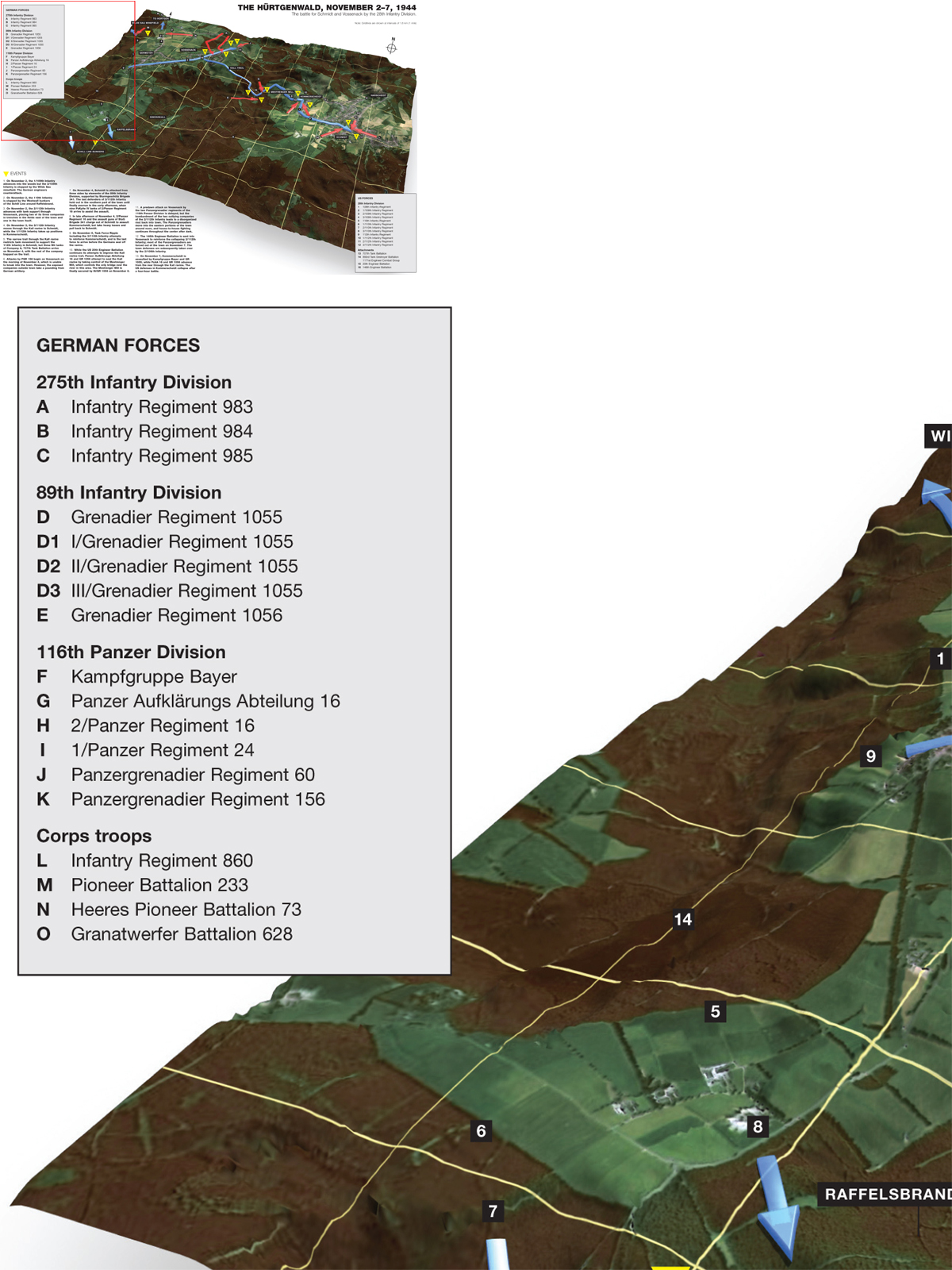

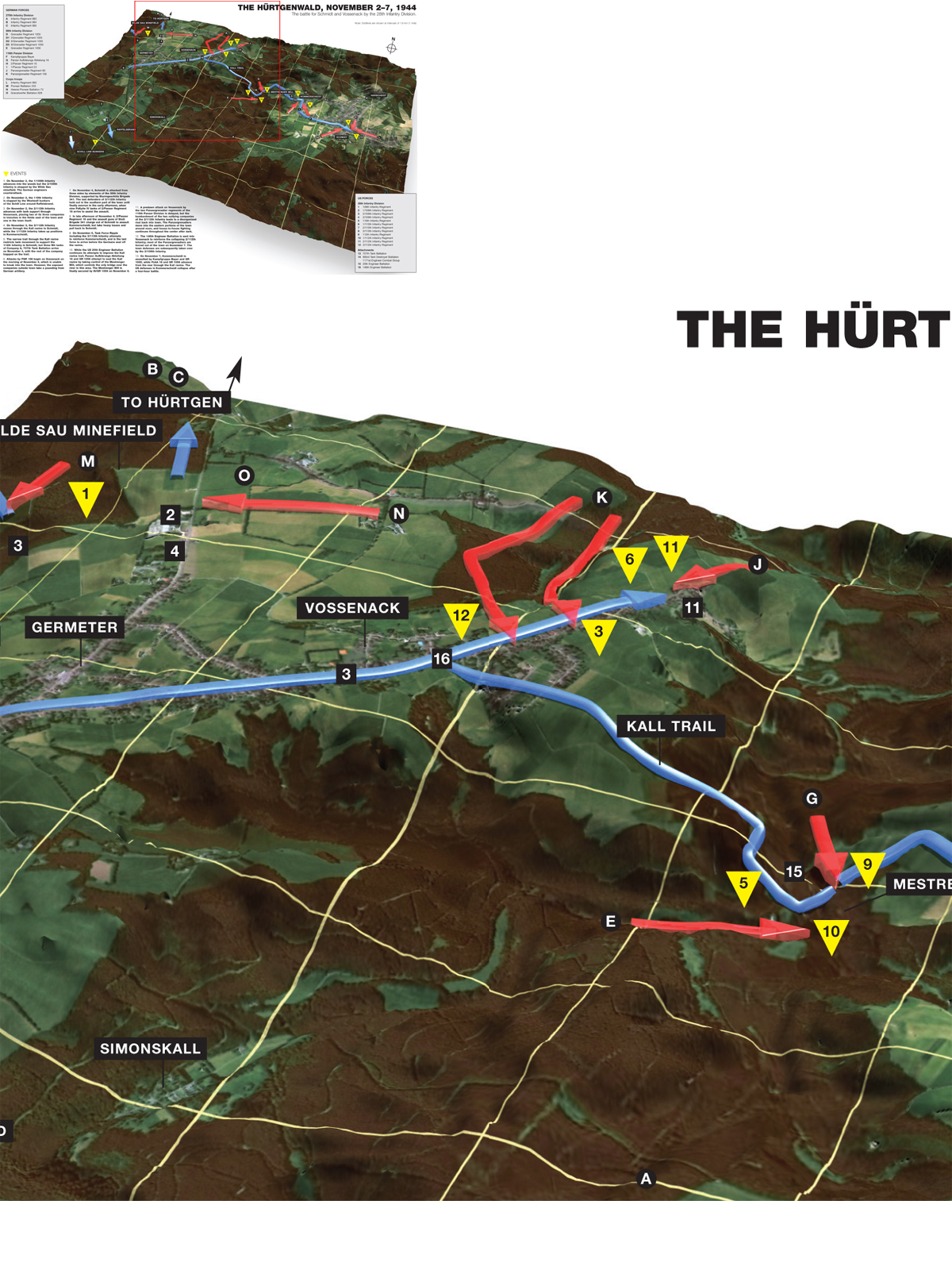

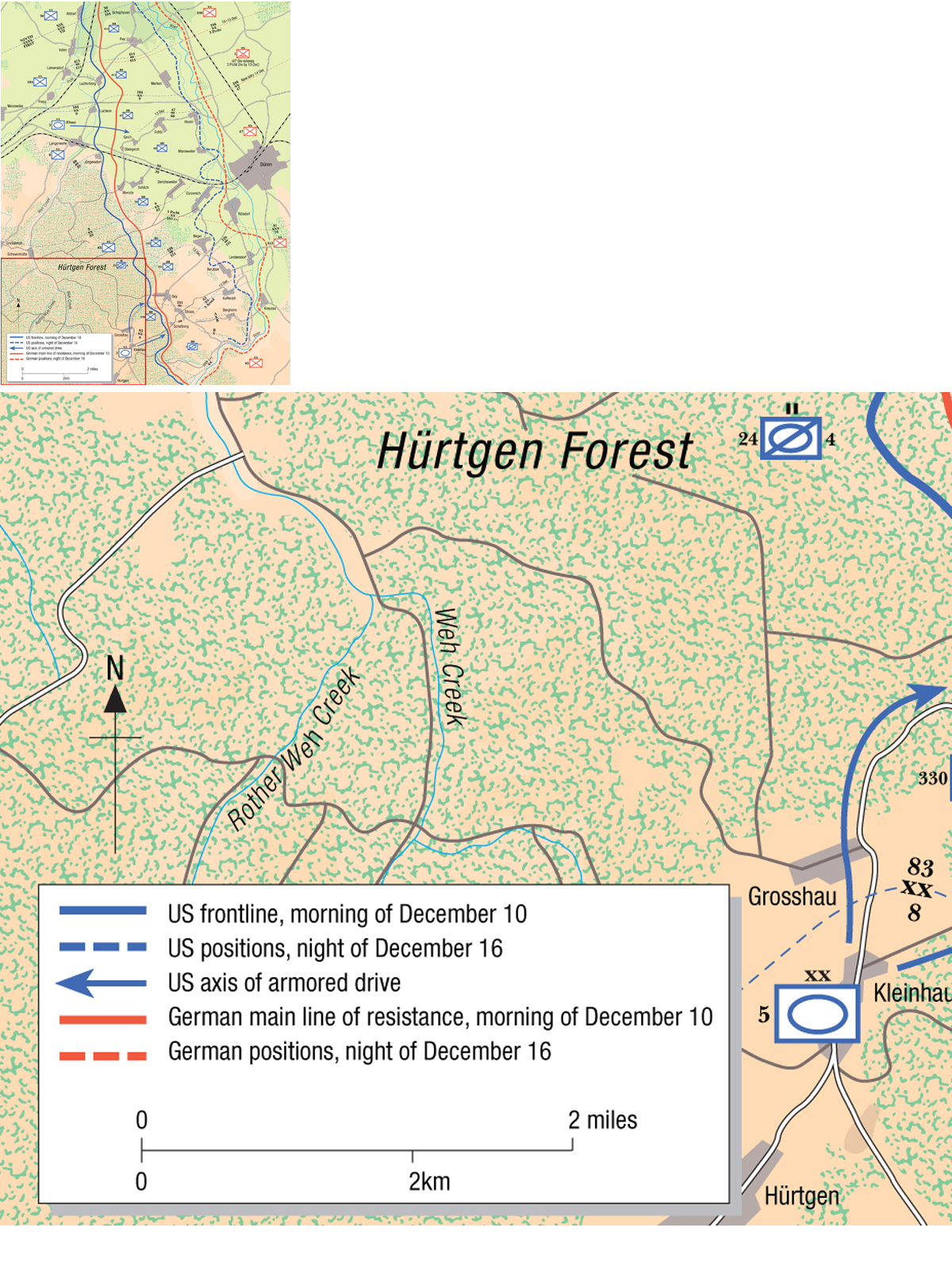

What would prove to be the most controversial element of the plan was in fact one of its secondary efforts – a preliminary operation to push through the towns in the center of the Hürtgen forest. The desire to clear this area of the Hürtgen forest had several tactical goals: it was the first step in clearing a pathway to the key road junction at Düren and providing the First Army with tactical maneuver room beyond the constricted Stolberg corridor; and it would serve to undermine lingering German defense of the Monschau area by threatening them from the rear. Beyond the tactical rationale, Hodges and Collins were both uncomfortable with their flanks exposed to possible German counterattacks out of the forest, though given the terrain conditions this threat was remote. The 9th Infantry Division had already pushed through the western part of the woods, but the attack stalled after reaching the open ridgeline that controlled the road from Hürtgen, through Kleinhau and Grosshau, which provided access to the River Roer plain in front of Düren. The expectation was that this mission would take a few days, since German resistance in the sector was expected to be limited to a few battered infantry elements of the 275th Infantry Division numbering only about 3,350 troops. The Hürtgen operation was scheduled to be launched on November 2, three days before the main assault, so that once the mission was completed, another attack could be launched through the town of Hürtgen, and then northward to Düren. Since the 9th Infantry Division was spent, the corps boundaries were shifted, with Gerow’s V Corps taking over the Hürtgen sector and substituting the 28th Division for the 9th Infantry Division.

A view of the Hürtgenwald from a clearing on the Raffelsbrand plateau, looking over the Kall ravine where the 110th Infantry was committed during the November fighting. (NARA)

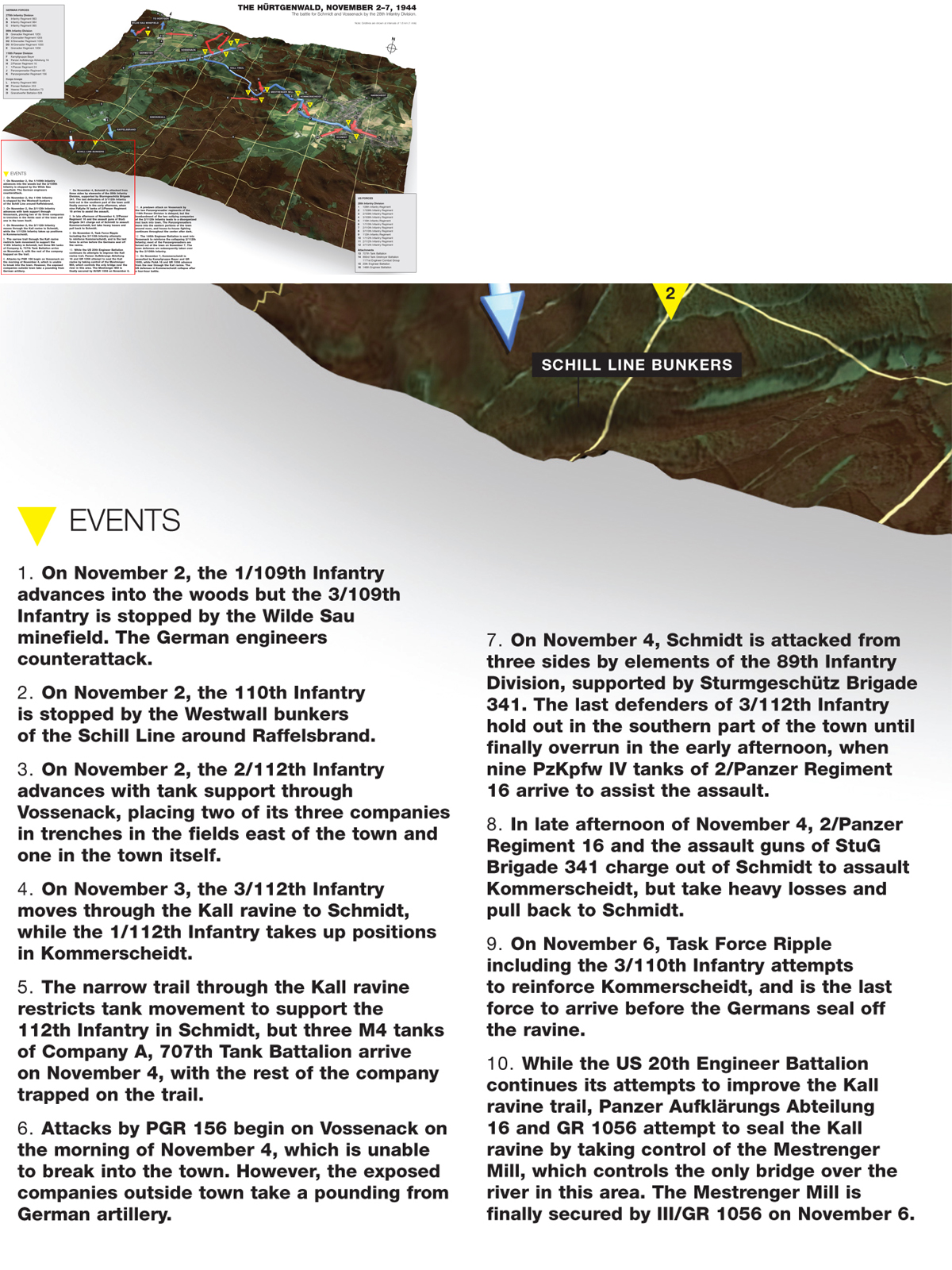

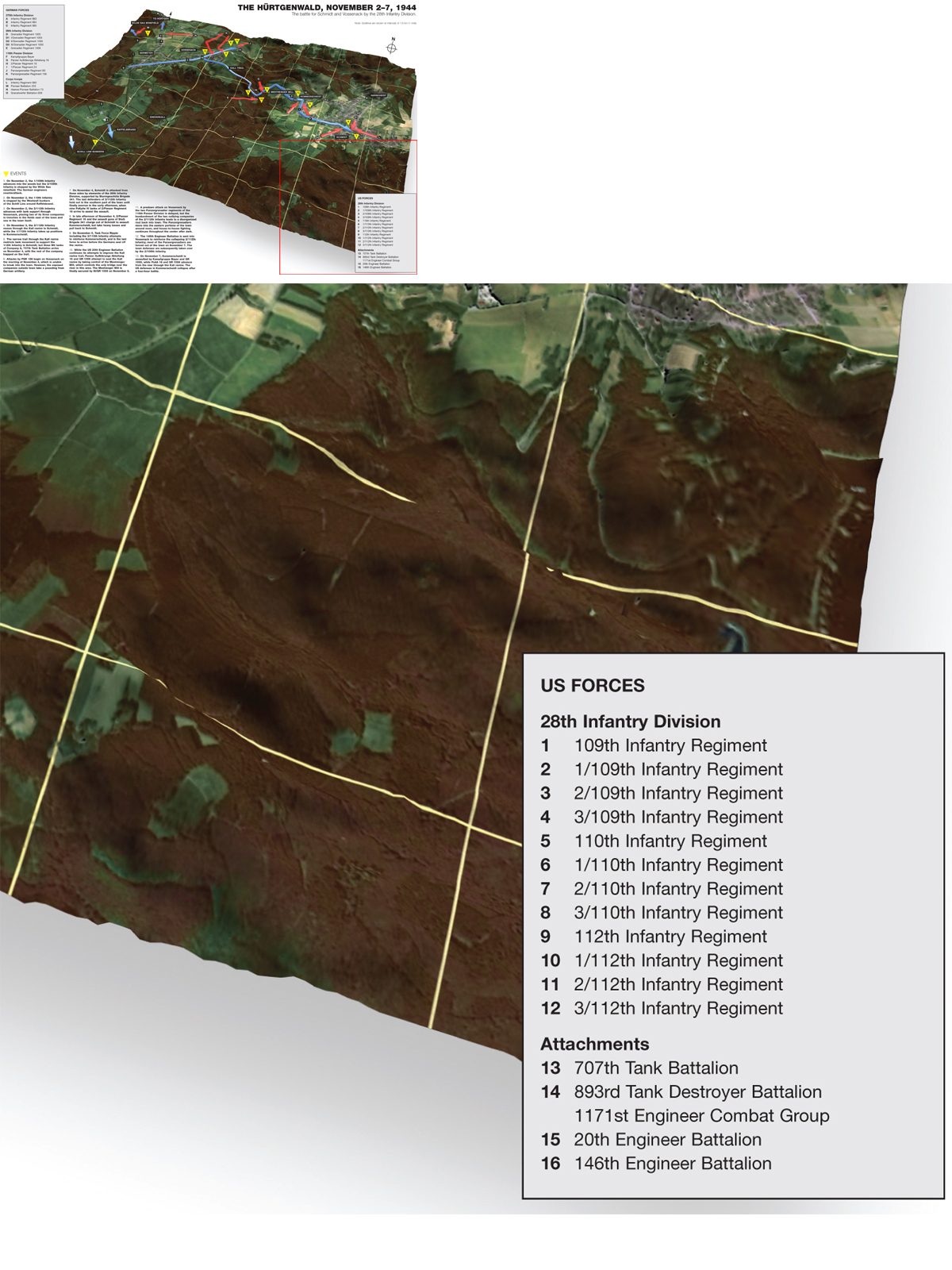

The 28th Division’s three regiments covered a front about three miles wide, and each was assigned a separate mission. The northernmost regiment, the 109th Infantry, was assigned to push north towards Hürtgen as a feint and to secure a launch point for a subsequent attack on Hürtgen. The 112th Infantry in the center was assigned to launch the main attack: a two-pronged drive through Vossenack with the second thrust pushing southeast to capture Schmidt. The 110th Infantry to the south was assigned to push into the clearing east of Lammersdorf in order to secure roads to eventually reinforce and supply the 112th Infantry in Schmidt, since there were hardly any useful roads between Vossenack and Schmidt aside from a single dirt trail up the sides of the River Kall ravine. The plan underestimated the German defensive potential in the woods and the difficulties of conducting infantry operations in the mountainous forest.

In the meantime, the Germans were reconfiguring their dispositions near the Hürtgenwald (Hürtgen forest), expecting an American attack at any time. On October 22, the 5th Panzer Army was brought in to take over 7th Army’s left flank from Geilenkirchen to Düren, including the western edge of the Hürtgen forest. This was necessary due to the increasing importance of the Aachen sector and the overextension of the 7th Army. This created some tactical issues, since the boundary between the two armies ran along the 81st and 74th Corps boundaries through the forest. As a result, on November 2, the staffs of both armies along with key commanders were brought together by GFM Model at Castle Schlenderhan to conduct a command-post exercise to game possible responses to a US attack near the corps boundaries in the Hürtgenwald. Coincidentally, this occurred at the same time as the US attack, and the initial German response was facilitated by the presence of so many commanders together with Model.

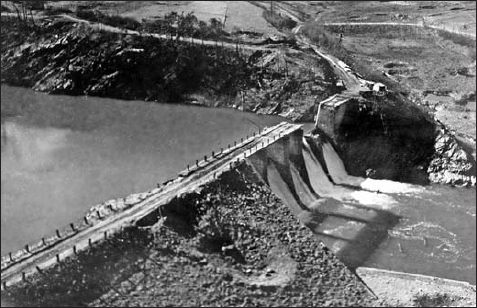

The German perspective of the Hürtgenwald was significantly different from the US appreciation. The senior German commanders anticipated that the principal US mission would be to strike immediately northward to seize the open ridgeline and the associated road network stretching from Hürtgen through Kleinhau and Grosshau as an avenue to reach Düren. As a result, German defenses opposite the US 28th Division were heaviest along its northern shoulder. Two of the 275th Infantry Division’s regiments were located there as well as a corps engineer battalion, working on the Wilde Sau (“Boar”) minefield blocking Hürtgen. The Germans were also concerned about the presence of dams in the Hürtgenwald linked to the Schwammenauel Reservoir, which controlled the water flow into the plains around Düren along the River Roer. Should the US Army advance over the Roer without first controlling the dams, the Wehrmacht could unleash the dams and flood the Roer plain. This had not yet been appreciated by Hodges and the US First Army, though it would later play a key role in prolonging the fighting in the Hürtgen forest.

An M10 3in. GMC of the 893rd Tank Destroyer Battalion moves forward along a firebreak in the Hürtgenwald west of Germeter on November 4, in an attempt to reinforce the 112th Infantry. (NARA)

The German tactical approach to combat in the Hürtgen forest was also different from the American appreciation. Based on the September fighting between the 89th Infantry Division and the US 9th Infantry Division, the German commanders believed that it was most prudent to defend from the forest not the towns, since this denied the US Army two of its most potent weapons – air support and artillery. The autumn weather was already greatly limiting Allied air operations, but the forested defenses were very difficult to identify and strike from the air even on clear days. Artillery was not very effective in wooded areas against troops deployed in log-reinforced dugouts, since the rounds detonated in the trees overhead, and the log roofs protected the occupants from the shrapnel. In contrast, German artillery was very effective against attacking American infantry. Exposed infantrymen were very vulnerable to the overhead artillery bursts and the artillery’s lethality was increased by the spray of tree splinters.

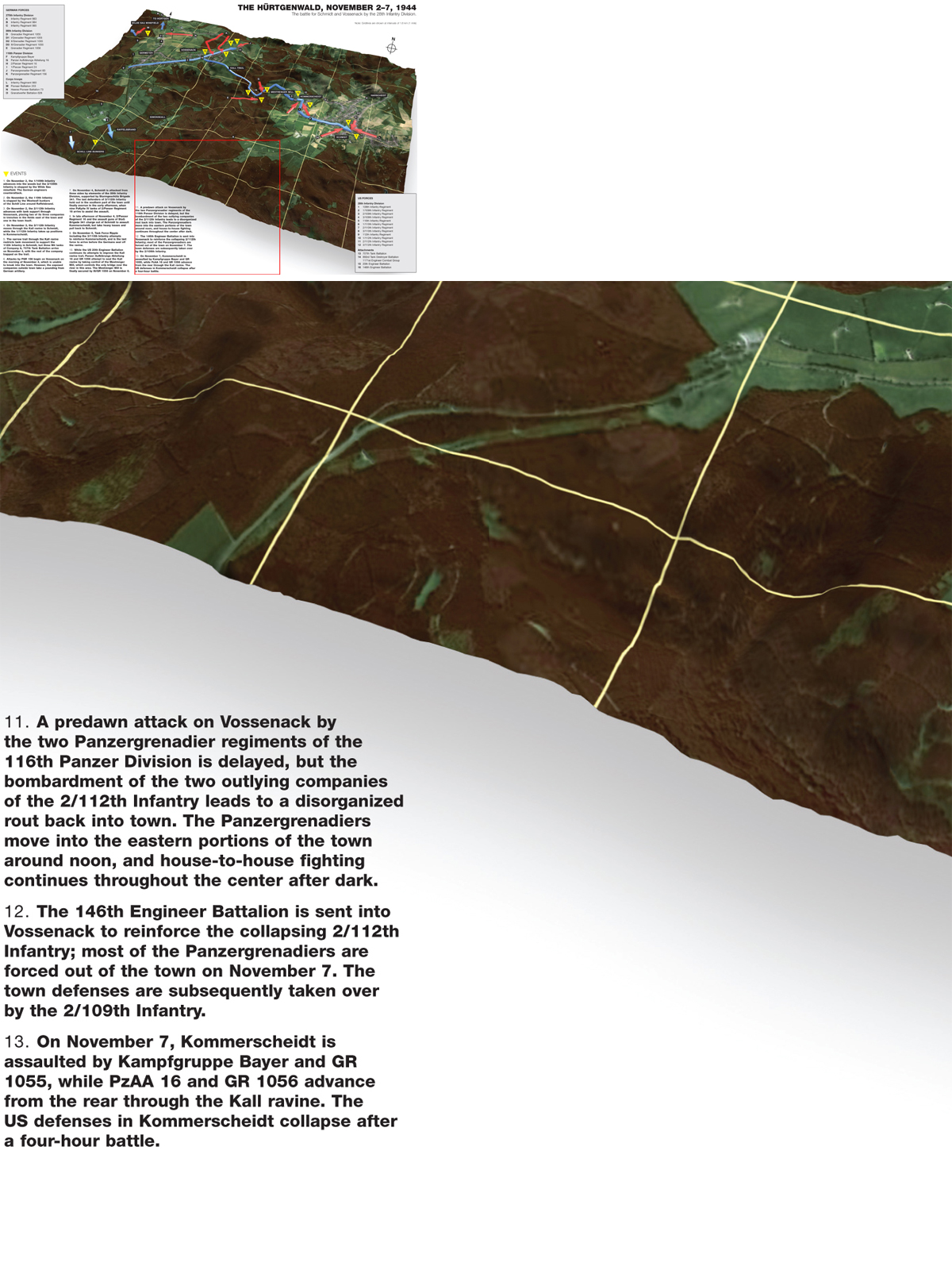

The 28th Division began its assault on November 2, but the attacks on either wing progressed poorly from the outset. The 109th Infantry was immediately halted in the Wilde Sau minefield and counterattacked through the woods by the German engineers. On the southern wing, the 110th Infantry immediately encountered the defensive bunkers of the Schill Line around Raffelsbrand, and soon became caught up in the barbed-wire entanglements under intense machine-gun fire from the German bunkers and dugouts.

THE HÜRTGENWALD DEFENSES, SEPTEMBER 1944 (pages 54–55)

This scene shows a typical Hürtgenwald defense line such as that occupied by the German 89th Infantry Division while fighting against the US 9th Infantry Division in September 1944. In this case, the defense hinges on a Westwall machine-gun bunker (1). There were relatively few bunkers built in the Hürtgenwald due to the difficulties of the terrain, and they were generally positioned to cover key firebreaks, river crossing points, roads, or other significant objectives. In many cases, accompanying trenches were built at the same time as the bunkers, though in other cases they were constructed in August–September 1944 when an effort was made to refresh the Westwall after years of neglect. The trenches (2) are log-lined to prevent their collapse during the incessant autumn rains. They were dug in a zigzag fashion to limit the damage caused either by a shell impact or the intrusion of enemy infantry. In the case of a straight trench, the artillery blast would devastate the whole section of trench, or an enemy infantry attack could likewise wipe out a whole detachment if exposed in a straight line. These trenches also had small log-covered bunkers (3) either built into the trench line itself or located nearby to provide the infantry with cover from artillery attack. Although not visible here, there were usually minefields emplaced some distance in front of the trench line, and on occasion, barbed-wire entanglements were added to cover especially important defensive positions. Infantry defenses in the Hürtgenwald typically took advantage of hills, as seen here, since they provided the defenders with firepower advantages as well as presenting an attacking infantry force with greater difficulty in reaching the objective. Forest defenses were particularly effective against the US Army since they minimized the US advantage in artillery and airpower. Artillery strikes tended to detonate in the high fir trees above. While this could enhance the blast and splinter effect against exposed infantry, it actually had less effect on defenders in log bunkers than did detonations on the ground. Likewise the forest provided cover against air observation, which limited the effect of close air support. Eventually, the incessant fighting and repeated artillery strikes in the Hürtgenwald stripped away much of the tree cover, denuding the slopes and exposing the defensive trenches to artillery fire. The infantry here shows the gradual shifts in firepower evident in the autumn of 1944, with wider use of Panzerfaust antitank rockets (4) and new weapons such as the MP44 assault rifle (5).

The central American thrust by the 112th Infantry encountered little opposition at first. The 2/112th Infantry was able to advance with tank support along the Germeter–Vossenack road towards Schmidt. Having captured Vossenack without undue problem, the battalion took up defensive positions with one company in the town itself and the two other companies in a defensive semicircle in the fields east of the town under the enemy-controlled heights of Bergstein. This disposition would prove to be a tragic mistake as it left most of the defenders in open trenches exposed to the miserable cold and autumn rains with little protection against German artillery fire except for their waterlogged trenches.

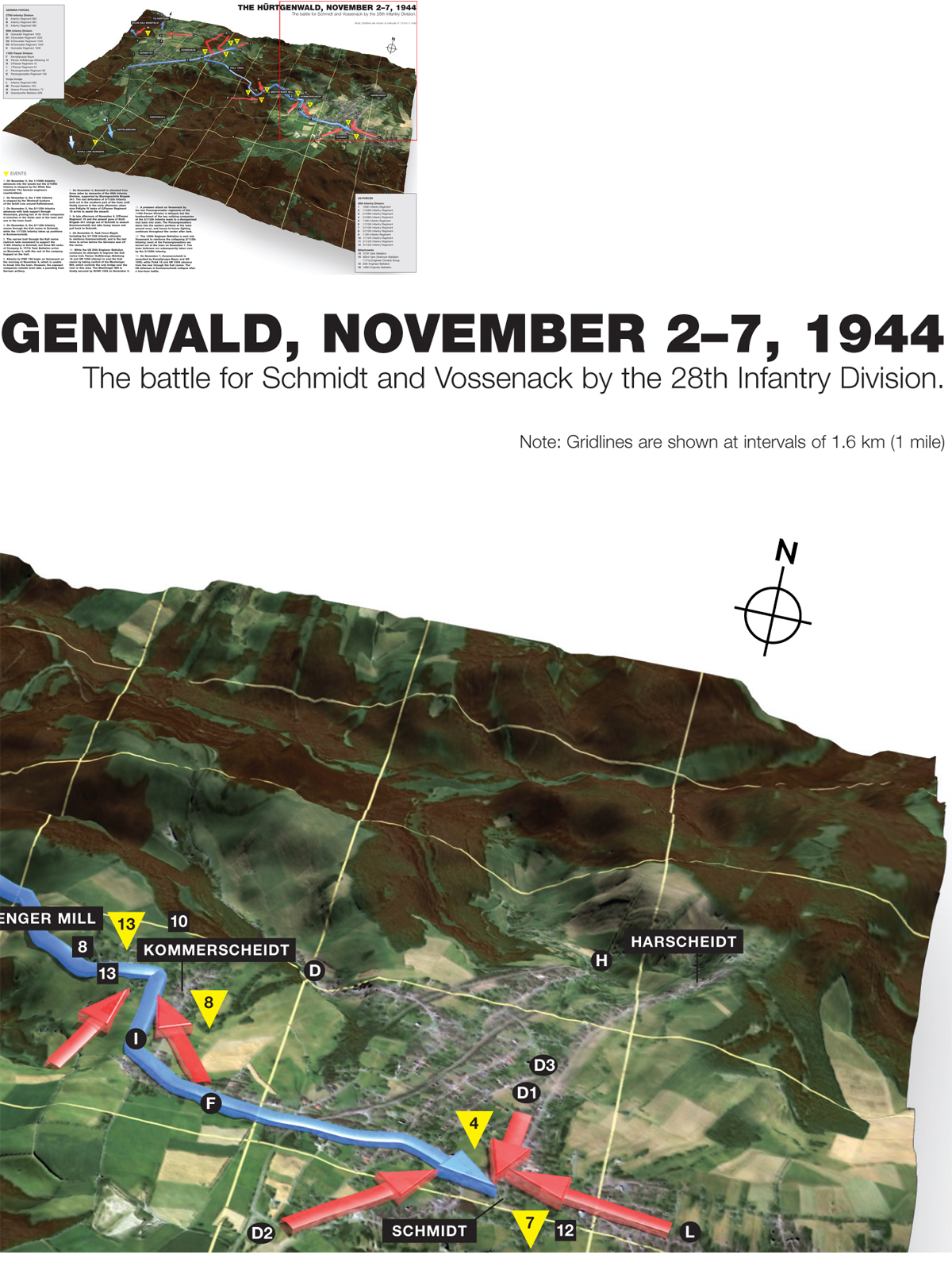

The 112th Infantry commander, Col Carl Peterson, began the advance to Schmidt the following day with his other two battalions. There was no real road between Vossenack and Schmidt, only a narrow, winding dirt track through the forested Kall ravine. On November 3, the 3/112th Infantry moved through the Kall ravine and proceeded into Schmidt, with the 1/112th following behind and occupying Kommerscheidt.

With the German staffs conferring with Model at the time, the Wehrmacht response was unusually swift. With news of the attack towards Schmidt rather than Hürtgen, Model presumed that the Americans were heading for the dams and so had to be stopped. Unhappily for the US 28th Division, the German 74th Corps was in the process of pulling out the 89th Infantry Division for refitting from the sector south of the US attack and replacing them with the 272nd VGD. Although the 89th Division was badly understrength, it was readily at hand and familiar with the local terrain, having fought around Vossenack and Schmidt a month earlier against the US 9th Infantry Division. The 89th Division was ordered to turn around and recapture Schmidt. Since the rest of the Aachen front was quiet, Model agreed to reinforce the 89th Division with the sector’s best mobile reserve, the 116th Panzer Division, which was refitting east of Düren. The Panzer Aufklärungs Abteilung 116 (Armored Reconnaissance Regiment 116) was the first element of the division to arrive in the area. It was fairly well equipped by Wehrmacht standards with about 785 men, eleven SdKfz 234 heavy armored cars, 53 SdKfz 251 personnel half-tracks, and 30 SdKfz 250 light half-tracks. The rest of the division followed behind. At the time, the division was at 83 percent of authorized strength, with about 12,550 men and over 50 Panzers. The division’s mechanized Panzergrenadier regiment, PGR 60, had 94 SdKfz 251 half-tracks, while its other regiment, PGR 156, was truck-borne.

The 3/112th Infantry in Schmidt was without tank support due to the poor road network in the area. Three tanks finally made their way up the Kall ravine trail to Kommerscheidt around dawn on November 4, but in the process several other tanks lost their tracks and effectively blocked the trail for any further reinforcements.

The German counterattack began on the morning of November 4. Despite the commander’s complaints, a hasty attack was launched by Panzergrenadiers of the 116th Panzer Division against Vossenack, but this failed to make much progress and was forced back to its start line by determined US infantry defenses stiffened by tank support. However, the 2/112th Infantry took a pounding all day long from an extensive array of German artillery, including the divisional artillery of both the 275th Infantry Division and 116th Panzer Division as well as Volks Artillery Corps 766, Granatwerfer Battalion 628 with 21cm rockets, and Sturmgeschütz Brigade 394.

The sole link between the battalions at Kommerscheidt was this narrow dirt trail up the side of the Kall ravine, barely wide enough for a tank to pass. Several tanks became bogged down on the trail after losing their tracks, blocking it at critical moments during the battle. Their tracks can still be seen here littering the sides of the hill, weeks after the fighting has ended. (NARA)

Schmidt was much more vulnerable to counterattack, being at a road junction. The town was hit from three sides by elements of the 89th Infantry Division supported by Sturmgeschütz Brigade 341; the US battalion in Schmidt was outnumbered by over three to one. Aside from a small number of antitank mines, the only antitank defenses in the town were bazookas, and these proved ineffective against the attacking assault guns. By noon, the German infantry had seized the northern and western portions of Schmidt, and a last-ditch defense of the southeastern corner of the town was finally overrun in the afternoon with the arrival of nine PzKpfw IV tanks of 2/Panzer Regiment 16. With the momentum of the attack in their favor, the Panzers and assault guns charged out of Schmidt towards Kommerscheidt. The 1/112th Infantry defenses in Kommerscheidt were backed by three M4 tanks; three PzKpfw IV tanks were knocked out in quick succession and a fourth became trapped in a swamp even before reaching the town. The Panzers barreled into Kommerscheidt without infantry support and quickly lost three more in a short-range duel with the Shermans. The Panzers were forced to withdraw with their surviving five vehicles.

General Cota ordered Peterson to counterattack and retake Schmidt, a remarkably unrealistic order in the circumstances. The 1/112th Infantry was entirely exposed in Kommerscheidt, connected to the rest of the division by the thin muddy trail up the Kall ravine. The Panzer Aufklärungs Abteilung (PzAA) 116 made numerous attempts to cut this link starting on November 4, and the trail and the nearby river bridge at the Mestrenger Mill changed hands several times during the fighting on November 5. The attack by PzAA 116 was reinforced in the other direction by the Grenadier Regiment (GR) 1056 of the 89th Division, which had been slow to arrive due to the lack of roads in the area. The combined forces of the reconnaissance battalion and GR 1056 were ordered to capture the Mestrenger Mill, which controlled the only bridge over the River Kall. After prolonged fighting with US engineer units in the ravine, the Mestrenger Mill was finally secured on November 6. In an attempt to regain Schmidt, Cota formed Task Force Ripple around the 3/110th Infantry, which moved through the ravine on November 6 and established a defensive line behind Kommerscheidt near the edge of the woods. The ravine remained a confused no-man’s land, with German units intermingled with American units in the rough hills and foliage.

The 2/112th Infantry in Vossenack remained under assault for most of November 5, but the terrain made it much more difficult for the Germans to mass forces, and US artillery was able to break up some of the attempts. The attacks on Vossenack eventually involved both Panzergrenadier regiments of the 116th Panzer Division. The situation here was reaching breaking point due to the intense German artillery bombardment and the badly exposed positions of two of the three infantry companies in the rain-soaked fields outside the town. When a new company commander arrived on the scene to visit his exposed platoons, he found the troops in such a poor state that he wanted them all withdrawn for combat fatigue. The situation was not helped by the regimental headquarters, which reported back to divisional headquarters that it was still in excellent combat condition.

The 116th Panzer Division was ordered to launch a pre-dawn attack on Vossenack around 0400 hours on November 6 using the I/PGR 60 from the southeast and II/PGR 156 from the northeast, but the regrouping in the hills under rainy conditions delayed the attack by several hours. Nevertheless, an intense 30-minute bombardment took place anyway, pounding the exposed trenches outside the town one more time. Following the barrage, rumors began to spread through the beleaguered US infantry that the Germans had broken through and in the darkness, chaos broke out. As troops fled back into the town, they set off a wave of panic that peeled back platoon after platoon. Officers managed to hold back about 70 men, but most of the two companies fled back to Germeter. After days of mind-numbing artillery bombardment in water-logged trenches, rumors and exhaustion nearly led to the loss of the town. The German attack finally began around noon, conducted by two companies from the II/PGR 156. In the meantime, the US 146th Engineer Battalion was rushed into the town as improvised infantry. The I/PGR 156 attempted to reinforce the attack from the northwest, but heavy US artillery fire pushed it back. House-to-house fighting continued until well after dusk, with the Panzergrenadiers finally capturing the town church shortly before midnight. On November 7, the 146th Engineer Battalion counterattacked the remaining Panzergrenadiers of the 116th Panzer Division, who had fought their way into the eastern side of Vossenack around the church. By the end of the day, most of the town had been retaken with heavy German losses. Nevertheless, US losses had been far more severe. The extent of them within the 2/112th Infantry is evident from the pace of replacements: the battalion received 515 reinforcements on November 8 alone. The heavy losses suffered by the 28th Division had forced the V Corps to take notice and on November 7, the 4th Infantry Division dispatched its 12th Infantry to take over the 109th Infantry positions in anticipation of further attacks against Hürtgen but from positions further north. This permitted the dispatch of 2/109th Infantry to Vossenack to take over the positions abandoned by the 2/112th Infantry.

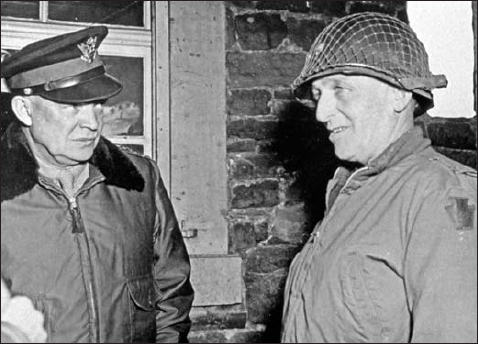

Eisenhower visits Gen Norman Cota’s headquarters to conduct a postmortem on what had gone so terribly wrong in the Hürtgen fighting. Cota (right) wears the keystone insignia of the 28th Division based on its origins with the Pennsylvania National Guard. After Hürtgen, the insignia was grimly known as the “bloody bucket.” (NARA)

On November 6, the 89th Infantry Division began organizing for a renewed counterattack against Kommerscheidt with Panzer support, while PzAA 116 along with GR 1056 cut off the US positions from behind through the Kall ravine. The attack began around dawn on November 7 from two directions. The fighting lasted for four hours, finally pushing the last US troops out of the town. In the meantime, the 28th Division had tried to form another task force under the assistant divisional commander, Brig Gen George Davis, but the force reached the Kall ravine only after Kommerscheidt had already fallen. Later that day, the remaining defenses east of the Kall were pulled back after Cota received permission from First Army. The disaster that had befallen the 28th Division led to a visit by all the senior US Army brass, including Eisenhower, Bradley, Hodges and Gerow. Divisional casualties to date had been 6,184, with the hapless 112th Infantry having suffered 2,093 battle casualties, as well as 544 non-battle casualties from combat exhaustion and trench foot. Total German casualties in this phase of the Hürtgenwald fighting were 2,900, and the 116th Panzer Division alone needed 1,800 replacements with GR 1055 needing 490.

The reasons for the debacle were many. To begin with, the attack plan dispersed the 28th Division on three separate and unco-ordinated missions leaving each regiment isolated. With two of the regiments tied down in the German defenses on the shoulders, this left the 112th Infantry exposed to the full force of two German divisions. The isolation of the battalions of the 112th Infantry due to the terrain allowed the Germans to destroy the 112th Infantry piecemeal, a battalion at a time. The dispositions of the 2/112th Infantry in Vossenack were poor, and Kommerscheidt’s isolation due to the Kall trail made it unusually vulnerable. The decision to postpone Operation Queen from November 5 to November 16 due to the poor weather doomed the 28th Division, since it allowed the German 7th Army to throw all of its reserves into the Hürtgenwald. This included a considerable amount of artillery, which was instrumental in reducing the 112th Infantry positions in Kommerscheidt and Vossenack, and also permitted the participation of the 7th Army’s operational reserve, the 116th Panzer Division.

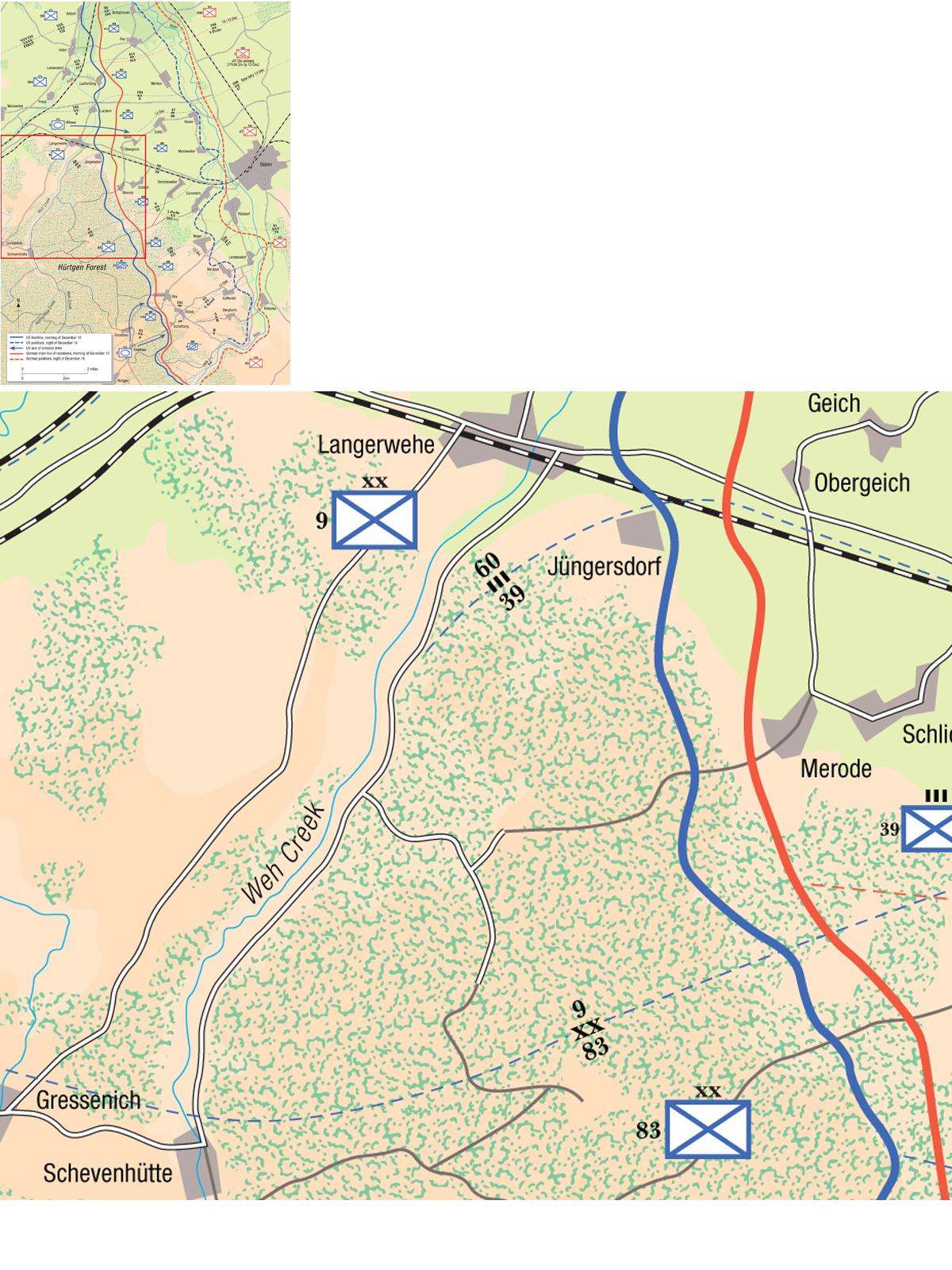

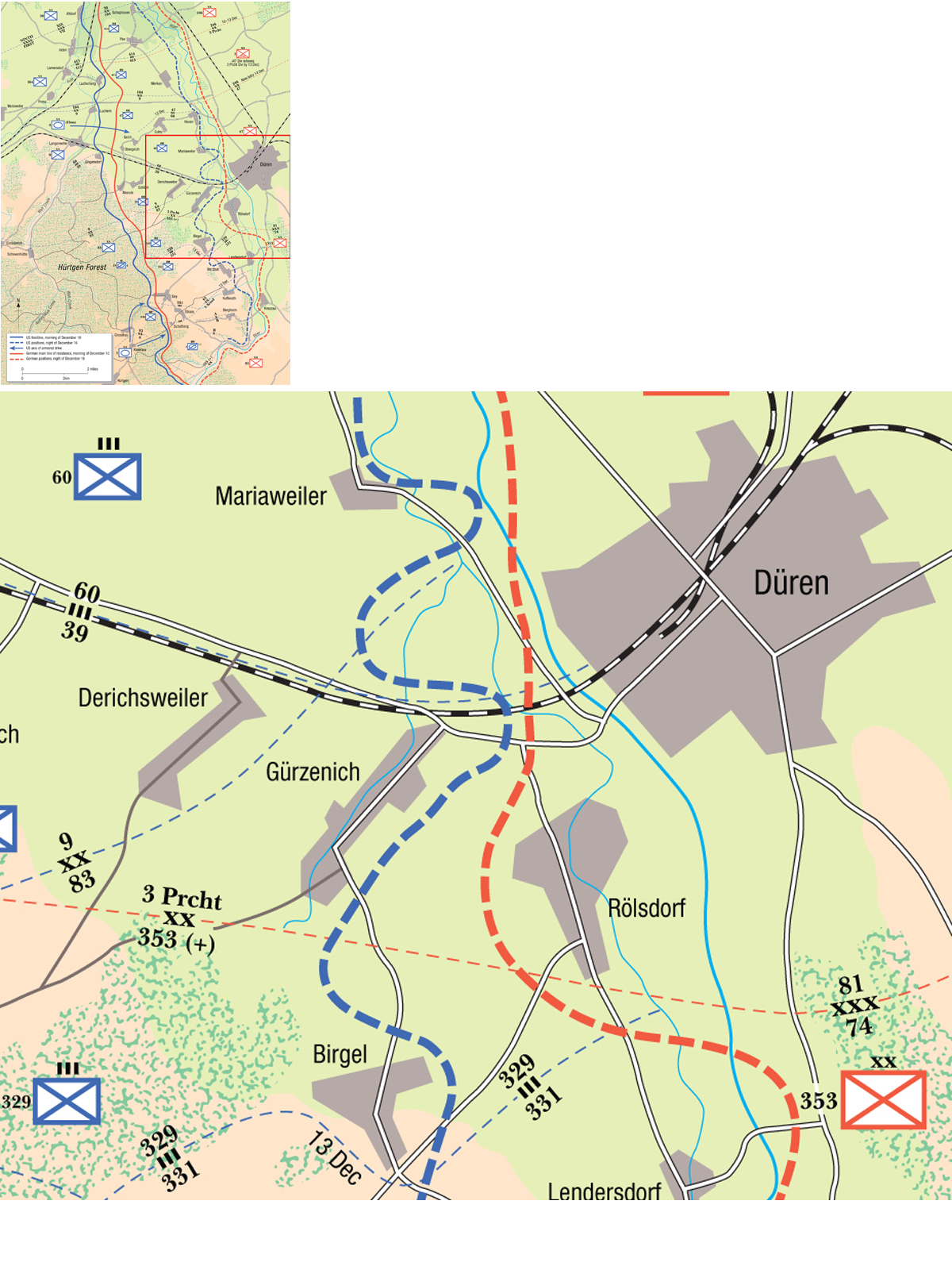

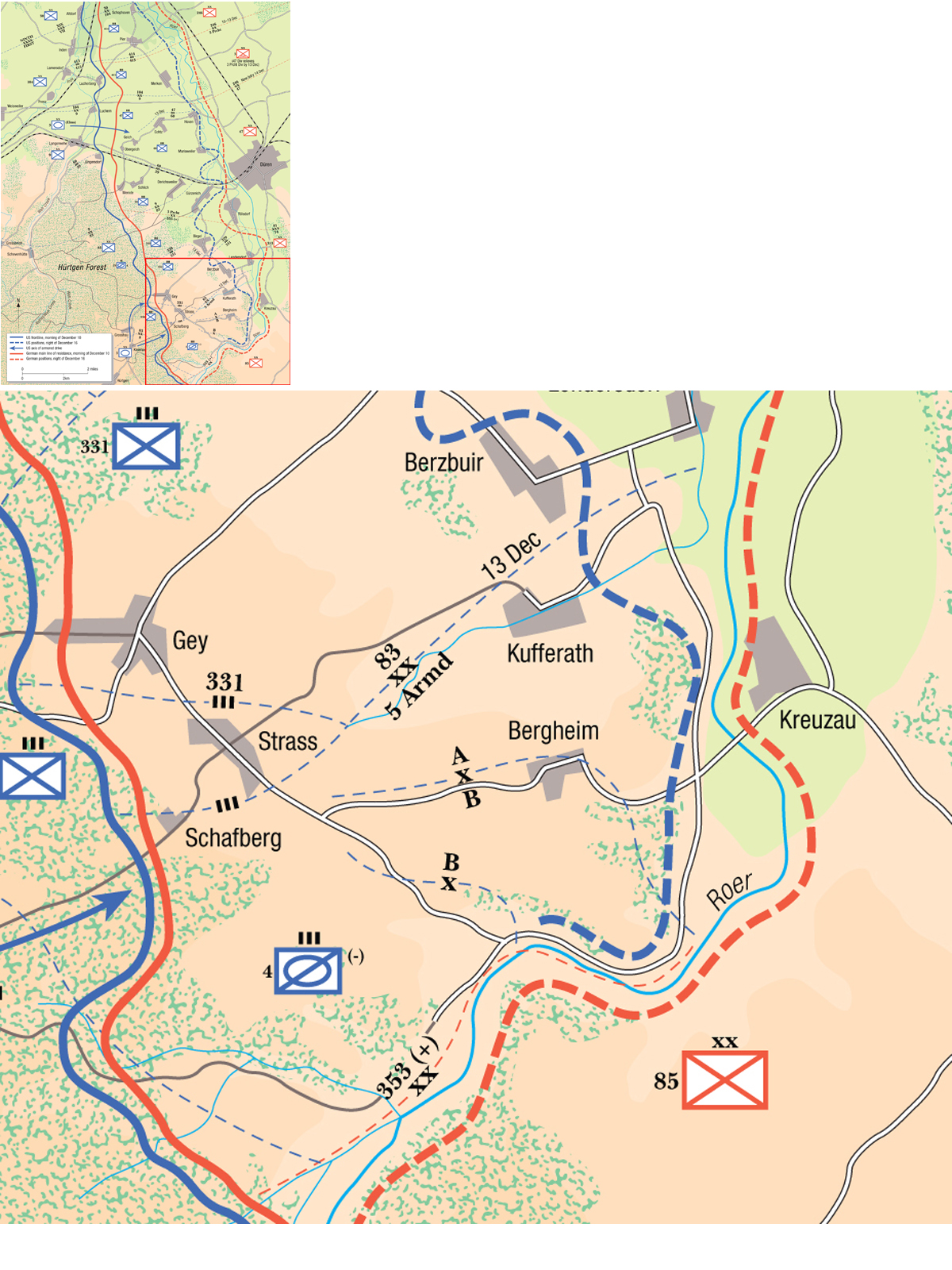

Bradley’s major autumn offensive, Operation Queen, was scheduled to begin on November 5, but was repeatedly delayed until November 16. The principal problem was the rainy and overcast weather that prevented the planned air strike, larger than any previous Allied air effort in the ETO. Bradley saw Operation Queen as a replay of Operation Cobra in Normandy, a massive air strike paving the way for a quick US Army breakthrough out of congested terrain into open tank country for a deep envelopment of German defenses. As in the case of Cobra, the starring role was given to the First Army and especially Collins’ VII Corps, which would push out of the Stolberg corridor towards the Roer. In the meantime, Gerow’s V Corps would be given the unenviable task of continuing to push back the German defenses along the edge of the Hürtgen forest towards Düren. The battleground for the First Army advance was constricted by the terrain, hilly and heavily urbanized in the VII Corps sector, and the forested hell of the Hürtgen in the V Corps sector. This time, two infantry divisions would be committed to the Hürtgen, the 1st to clear the northeastern fringes, and the 4th to attack straight into the forest to seize Hürtgen and the roads to Düren. By this stage the US Army had finally begun to appreciate the importance of the Roer dams in the forest, and Operation Queen presumed that the offensive would have to be halted along the Roer until the problem of the dams was settled.

The Roer front in November was a sea of mud, leading to many improvisations. Here, GIs of the 9th Division help the crew of an M4 tank of the 746th Tank Battalion attach a section of corduroy matting on the front of the tank on December 10 prior to the attack on Merode. The matting consisted of several logs tied together with wire and could be laid down as a carpet in front of the tank when particularly deep mud was encountered. (NARA)

Simpson’s neighboring Ninth Army was given the mission of pushing its forces up to the Roer on the left flank. The terrain in the Ninth Army sector was in some respects more favorable for advance, consisting of relatively flat farmland interrupted by many villages. The greatest challenge was the town of Geilenkirchen, positioned in the midst of a dense concentration of Westwall bunkers and sitting on the border between the US 12th Army Group and the British–Canadian 21st Army Group.

The German defenses in the sector had gradually improved, but were still operating on a minimum of forces while the best units were pulled back for refitting prior to the Ardennes offensive. Manteuffel’s 5th Panzer Army had taken over the northwestern sector for three weeks in late October, but, since it was an essential element of the Ardennes plans, the headquarters was pulled out and replaced by Zangen’s 15th Army under the phoney name of “Gruppe von Manteuffel” on the eve of the US offensive. During the lull in fighting in late October, the emphasis in this sector was to improve the defenses with mines, entrenched antitank guns, and redoubts for the infantry to protect them against artillery. Model’s operational objective was to keep the US Army bottled up west of the Roer. If the situation with the German infantry and Panzer units in the area was not particularly good, German artillery in the sector was relatively ample; a one-time issue of artillery ammunition from the Führer reserve was allotted to the 81st Corps, though this would be exhausted in a few days of heavy fighting. Like most of the industrialized areas of Germany, there were numerous heavy flak batteries, which made potent antitank weapons.

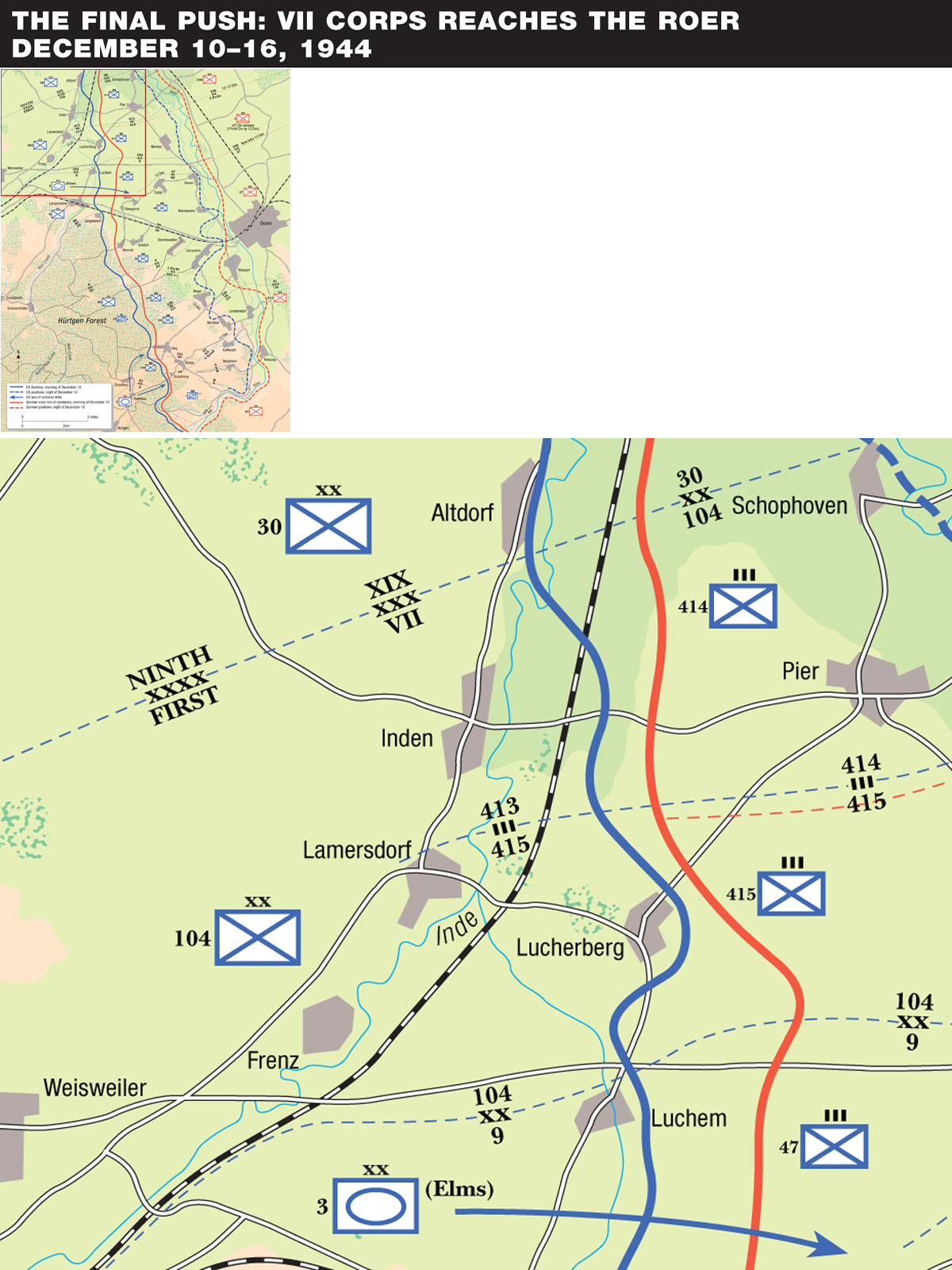

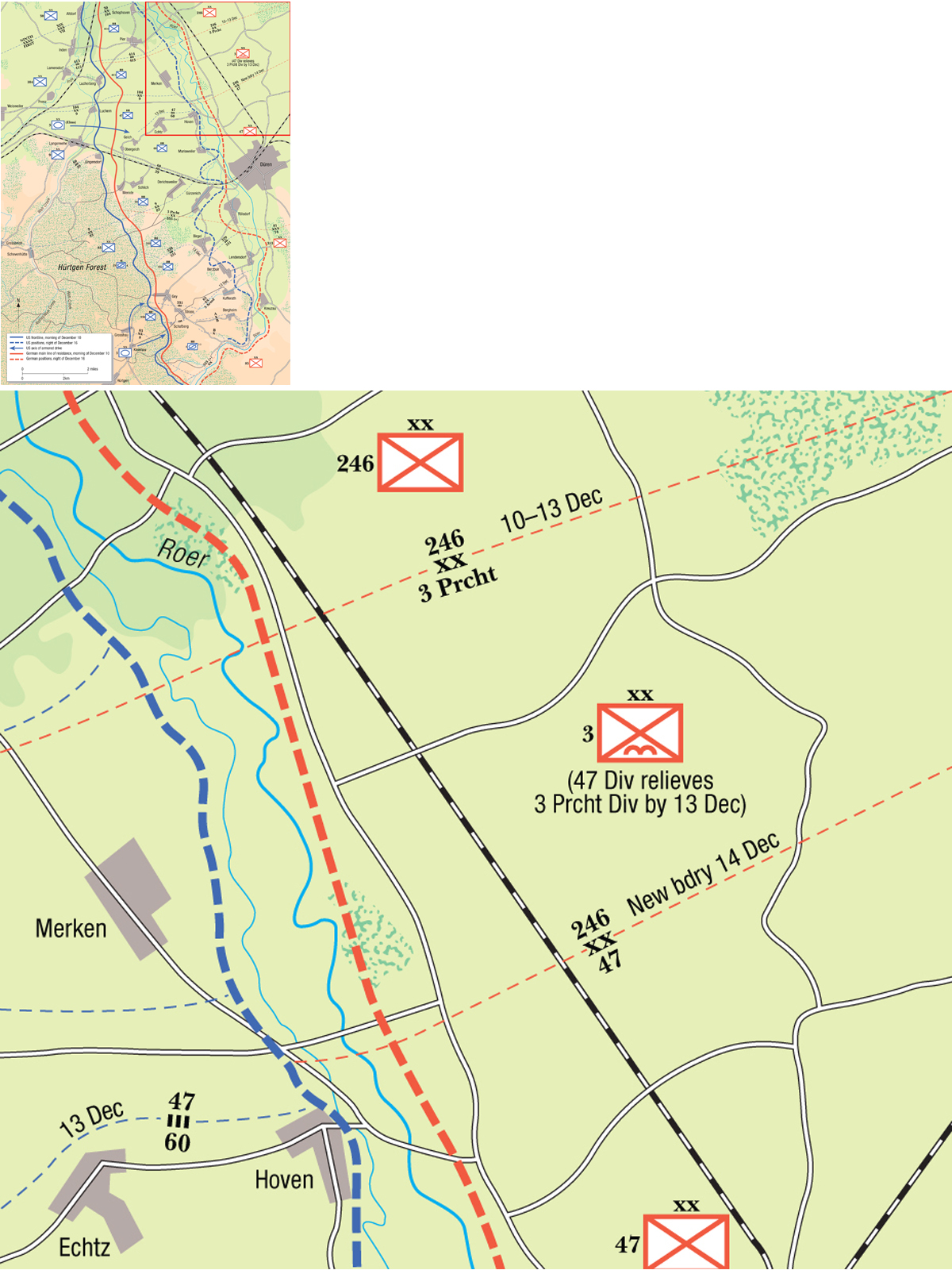

Collins’ VII Corps faced three German divisions in the Stolberg corridor: the 3rd Panzergrenadier Division, 12th VGD and 246th VGD. Two of these divisions had been fighting in this sector since September; the 12th VGD having been renamed by Hitler to honor its earlier performance. The 246th VGD had been resurrected after the surrender of its previous namesake in Aachen the month before. The 12th VGD was scheduled for replacement by the 47th VGD for refitting, and suffered the misfortune of carrying this out in the midst of the US attack. The 47th VGD had been rebuilt recently with half its infantry coming from the Luftwaffe and navy, and the other half from fresh 17–18-year-old recruits with only six weeks’ training.

The preliminary air bombardment on November 16 was directed mainly against the towns along the Roer. Heavy bombers from the US Eight Air Force delivered 4,120 tons and the RAF a further 5,640 tons. Air strikes by medium bombers and fighter-bombers were much more limited due to the lingering overcast. The air attacks did not have the dramatic effects of the Operation Cobra attacks since they were not directed against the German frontline positions. While the attacks certainly laid waste to several German towns, they caused very modest casualties among the Wehrmacht infantry. The main tactical effect was to severely disrupt German tactical communications, which relied heavily on wire and telephone networks that were shredded by the attack.

Pvt Robert Starkey of the 16th Infantry, 1st Infantry Division stands beside the burnt-out hulk of a Pzkpfw IV/70. Starkey knocked out this tank with his bazooka during the fighting near Hamich, Germany on November 22.

The only unit badly hit by the attack was the hapless 47th VGD, which happened to be coming off trains in stations along the line just as the bombers hit. One of its artillery battalions was annihilated in Jülich, the headquarters and support battalions were smashed up in Düren, and a number of infantry battalions were in the bomb zone as well. A seasoned German NCO later recalled the effect on the recent recruits: “I never saw anything like it. These kids were still numb 45 minutes after the bombardment. It was lucky that [the Americans] didn’t attack us until the next day. I could have done nothing with my boys that day.” The air attack was followed by a massive artillery preparation with the First Army firing some 45,000 light, 4,000 medium and 2,600 heavy rounds.

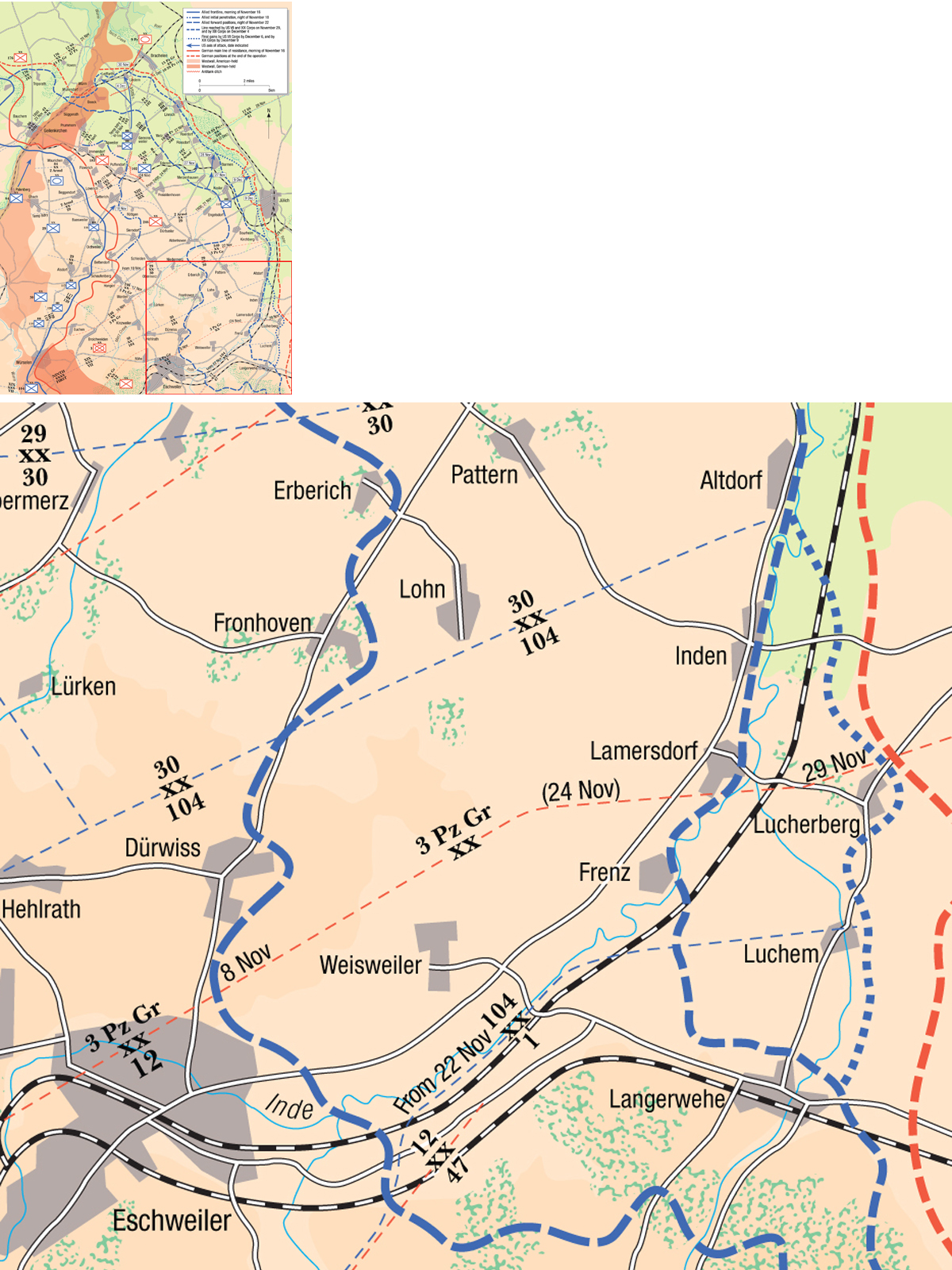

The VII Corps attack was conducted by the 1st Infantry Division on the right and the 104th Division on the left. The 104th Division was a recent arrival in the theater, commanded by “Terrible Terry” Allen who had commanded the 1st Division in North Africa and Sicily before running afoul of senior commanders for his pugnacious personality. The 1st Division attack made slow but steady progress against the fresh but inexperienced 47th VGD around the village of Hamich on the edge of the Hürtgen forest. A counterattack with support from the 116th Panzer Division was conducted on the night of November 18, but in the dark two battalions of GR 104 of the 47th VGD stumbled into US positions near Hamich and were decimated by small-arms fire and artillery. Nevertheless, the wretched autumn weather and appalling forest conditions assisted the 47th VGD’s defense, and, after four days of fighting, the 1st Division had penetrated only about two miles into the forest at a cost of a thousand casualties.

Collins planned to use CCA, 3rd Armored Division to support the 104th Division while CCB would operate independently to take a series of villages along the northwestern fringe of the Hürtgen, defended by their old adversary, the 12th VGD. The CCB tank advance was hampered by the mud and by the skillful deployment of long-range flak guns on the heights around Eschweiler. The hilly terrain on the route of advance gave the German defenders excellent observation of the approach routes of CCB, and a heavy toll was taken on half-track infantry and tanks alike. Although the CCB secured its initial objectives in three days, the casualties were appalling – about half the men in the two companies of armored infantry, and 49 of the 69 tanks. The causes of the tank losses give some sense of the nature of the fighting: six were lost to Panzerfausts, 12 to mines, 24 to guns, and six to field artillery.

A rifleman of the 104th Division prepares to fire a rifle grenade from his M1 Garand rifle during the fighting for Stolberg on November 16, 1944.

The 1st Infantry Division committed its reserves to a renewed attack past the industrialized Langerwehe– Jüngersdorf corridor. The 18th and the 26th Infantry remained engulfed in the fighting in the northwestern tip of the Hürtgen forest with predictably slow progress and painful casualties. The 18th Infantry battered its way past Heistern and approached Langerwehe through the woods. The 16th Infantry and the attached 47th Infantry fought to the west, in an area where the Hürtgen forest gradually gives way to the more open terrain of the Roer plain. Once again, the landscape was dominated by hills that overlooked the approach routes of the 1st Division and made it possible for the Germans to use their artillery effectively to stymie the advance. The defenders on Hill 187 near Nothberg proved to be particularly nettlesome opponents, and in sheer frustration the VII Corps authorized the use of virtually all the corps artillery – some 20 battalions, including a 240mm howitzer battalion – to blast the 300-yard crest for three minutes on November 21. When a US patrol made its way up the slope 12 hours later, they found nothing but the dead and 80 German soldiers too dazed to resist.

Collins began to realize that his hope for a quick breakthrough to the Roer had evaporated, so he began to use his exploitation reserve, the 3rd Armored Division, to facilitate the breakthrough. Task Force Richardson from CCA, 3rd Armored Division was added to the 47th Infantry and positioned in the open ground near Nothberg for an advance along the 1st Division’s left flank. In spite of the armored support, the attack was slow due to the mud, extensive minefields, and well-positioned German antitank guns. Following the capture of the castle at Frenzerburg, the Germans staged a vigorous counterattack. What alarmed the 1st Division was that these troops were from the 3rd Fallschirmjäger Division, the first major injection of German reinforcements into this sector since the beginning of Operation Queen. Rundstedt had only consented to its transfer from Holland if two other divisions could be pulled back for refitting for the Ardennes attack. In this case, the 12th and 47th VGD had been bled white in the fighting over the previous two weeks, and so were finally pulled out. In spite of its name, the parachute division consisted mainly of inexperienced troops, and the substitution of this raw division created temporary opportunities for the 1st Infantry Division. After pushing past Hill 203, the 16th and 18th Infantry finally exited the forest and fought their way into the ruins of Langerwehe, subduing Jüngersdorf as well by nightfall on November 28. It proved to be far more difficult for the 26th Infantry when it tried to push out of the woods at Merode, where two companies were surrounded and wiped out on November 29 by a combined attack of the German paratroopers and Panzers. By the beginning of December, the 1st Division was a spent force, having suffered 3,993 battle casualties, and more than 2,000 non-battle casualties.

At the outset of Operation Queen, the 104th Division advanced into the River Inde valley aiming for the hill town of Donnerberg, which had resisted numerous previous attacks. The initial attacks against the 12th VGD positions made little progress for the first two days of fighting, but, finally, three major bunkers were cleared on November 18, with the 414th Infantry gaining the heights. The other two regiments were kept idle until the heights were captured, and so did not begin major actions until November 19. The 413th Infantry aimed for the industrial town of Eschweiler, while the 415th Infantry was to clear the northern half of Stolberg. The 12th VGD put up a determined defense of Eschweiler, so Gen Allen decided to force them out by encircling the town. This worked, and late on November 21 Rundstedt authorized the 12th VGD to pull out of Eschweiler to more defensible positions, leaving the town open to the 104th Division. Gen Allen had taken great pains to train the division in night operations, and this came in handy on several occasions. In the renewed fighting after November 23, night attacks proved successful in cases where day attacks had faltered, as they prevented the German assault guns and direct fire artillery from observing the attack. The towns along the River Inde fell in succession, but the advance was costly due to German artillery, which at one point was firing at a rate of 50 rounds per minute. The pressure against the depleted 3rd PGD was so severe that the 246th VGD replaced the 3rd PGD in the fighting for Inden. After five days of fighting, the town was finally taken, setting the stage for crossing the River Inde towards the Roer. The main obstruction to the crossing was the town of Lucherberg, which was not secured until December 4. The next day the 3rd Fallschirmjäger Division executed a pre-dawn counterattack, but small-arms fire and an intense artillery response crushed the attack. In the three-day fight for Lucherberg, the 3rd Fallschirmjäger Division suffered about 850 casualties, compared to about 100 casualties in the 415th Infantry. The discrepancy was in no small measure due to the volume of artillery available to the 104th Division.

An M4A3E2 assault tank of the 745th Tank Battalion wades through the water and mud under a destroyed railroad viaduct in early December during the fighting for the industrial town of Langerwehe by the 1st Infantry Division. (NARA)

By mid November, Bradley and the rest of the senior leadership were finally aware of the threat posed by the Roer dams, and were determined to gain control of them as well as obtain another route to Düren. The difficulties of forest fighting had still not been fully realized by the senior leadership in spite of the horrible costs inflicted on the 9th and 28th Divisions in previous fighting. There was the hope that German defenses in the forest would be weakened by the demands elsewhere on the Roer front.

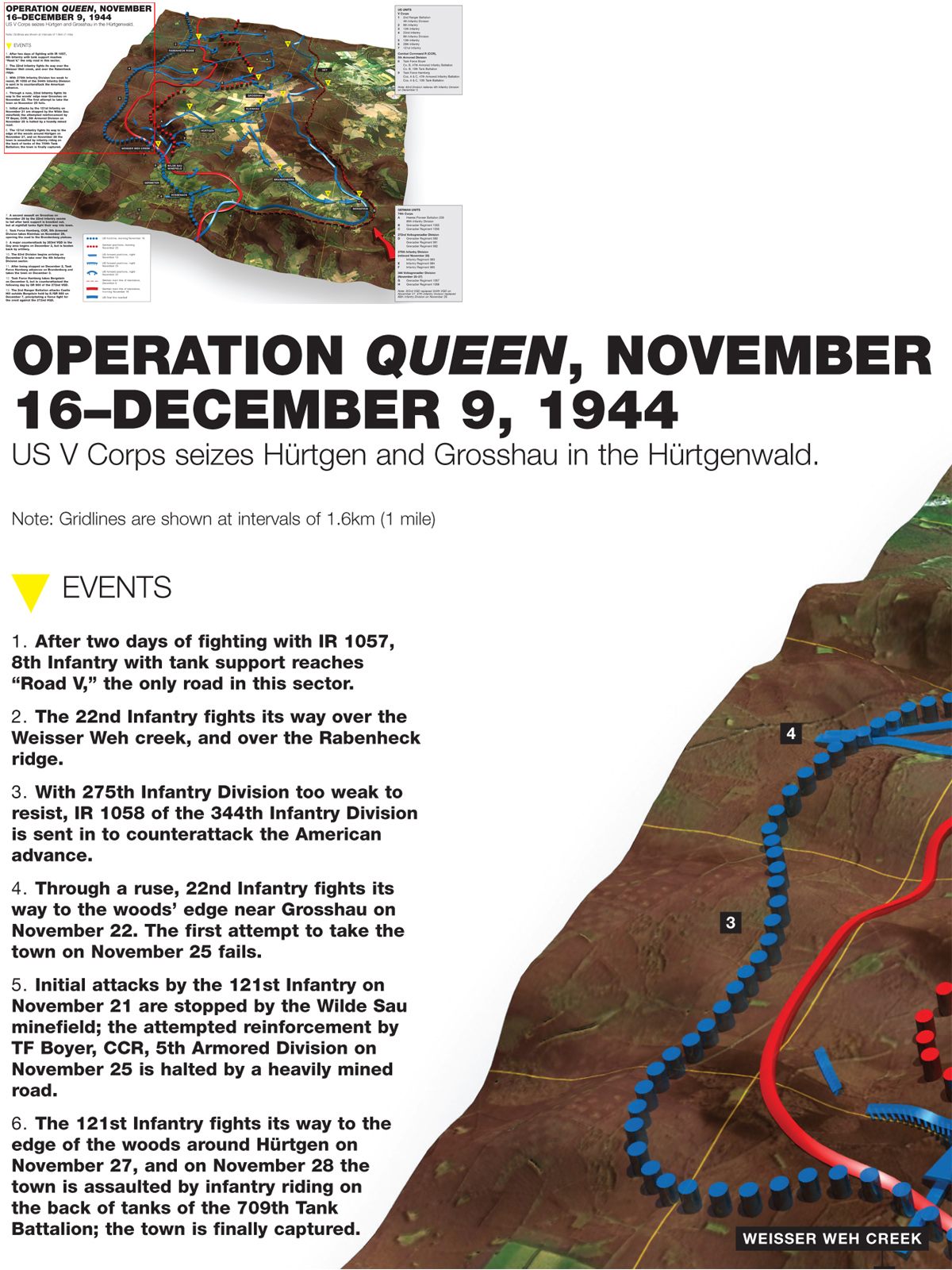

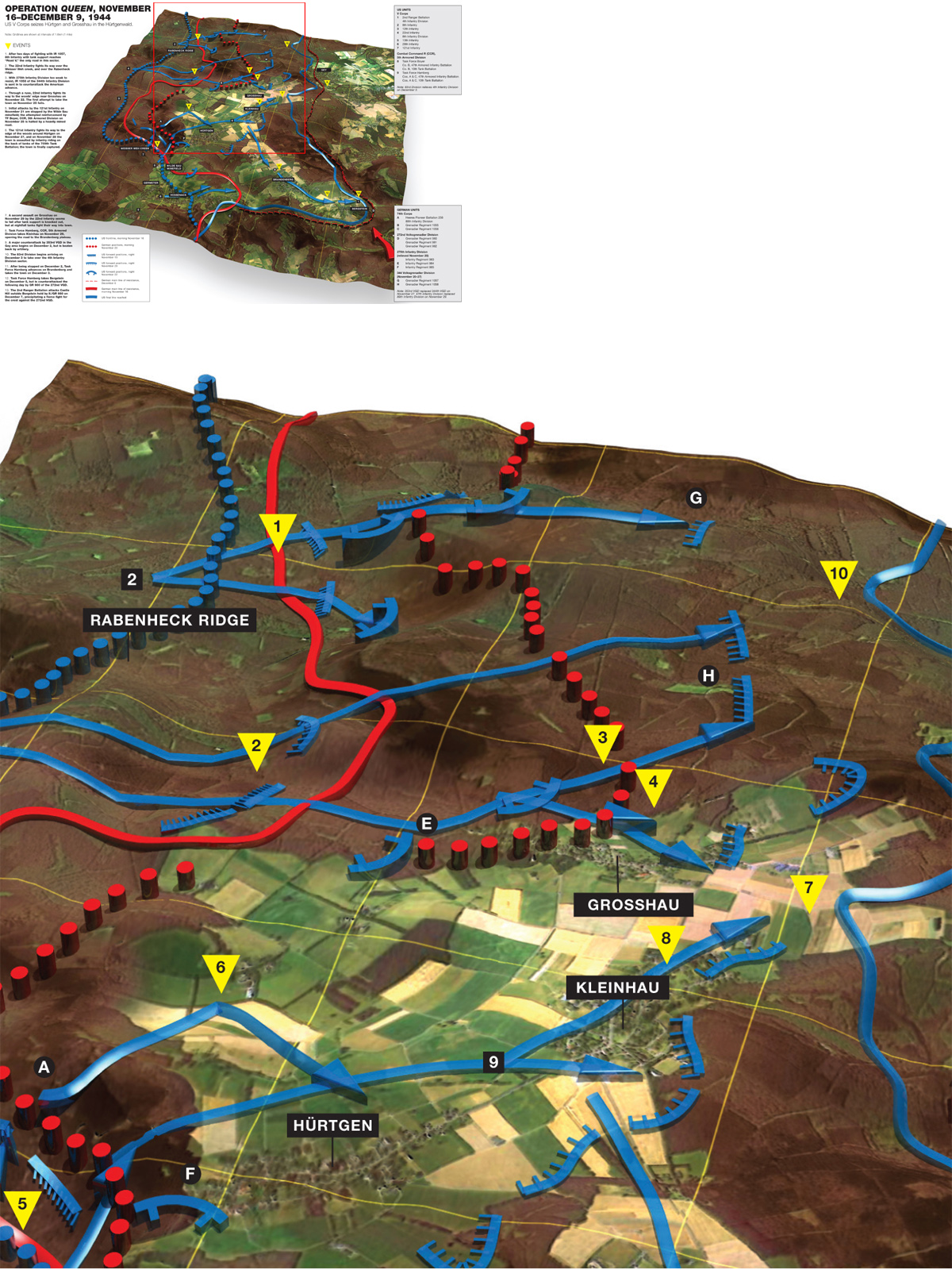

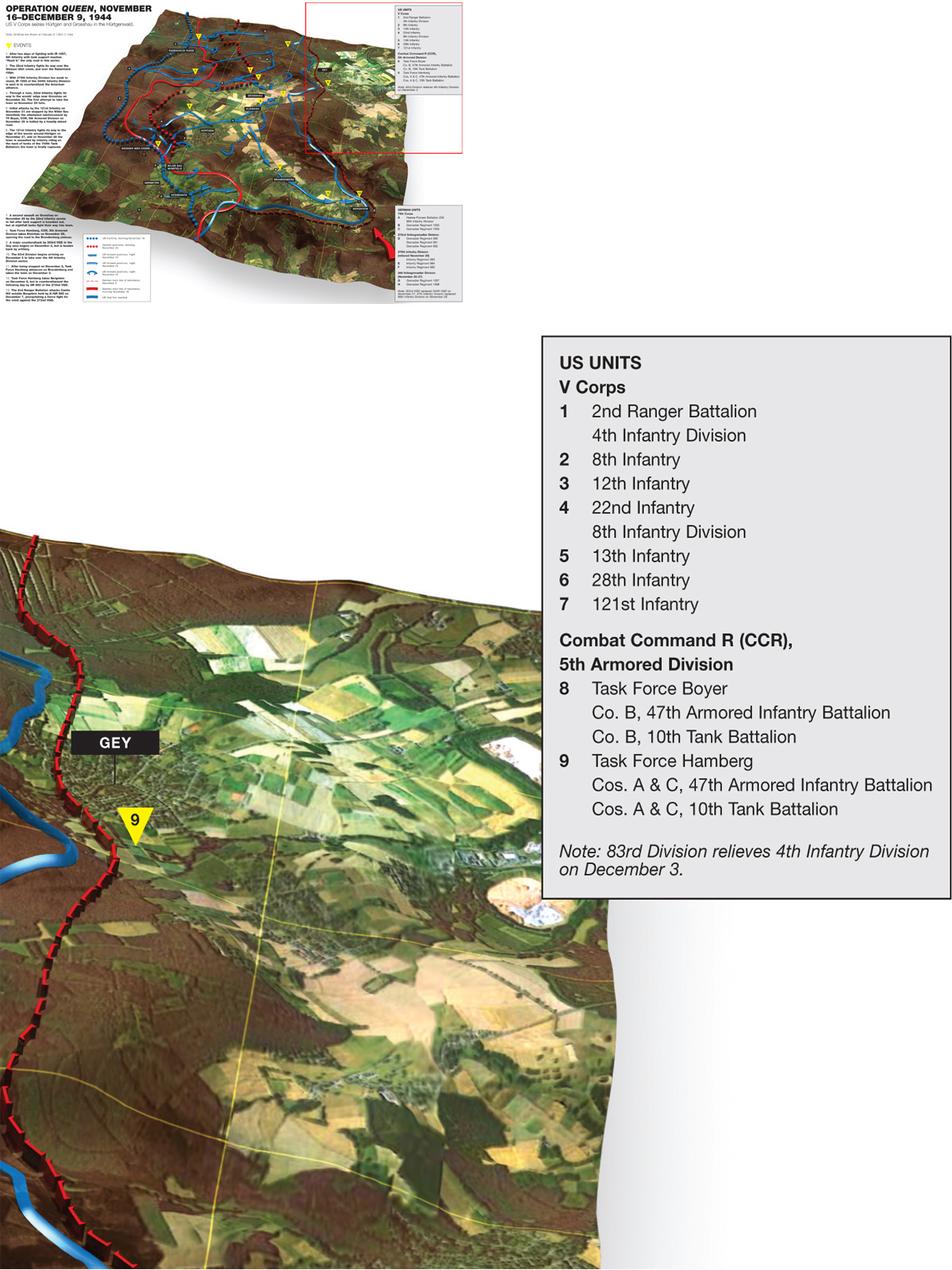

The main onus fell on the 4th Infantry Division, positioned further north than the hapless 28th Division. The 4th Infantry Division’s commander, Gen Raymond “Tubby” Barton, deployed the 8th Infantry on the left to cover the flank with the neighboring 1st Infantry Division from VII Corps; the 22nd Infantry was given the central task of pushing out of the forest to Grosshau on the Hürtgen ridgeline; and the 12th Infantry would maintain the right flank opposite Hürtgen in the sector formerly held by the northernmost of the 28th Division units. The intelligence assessment suggested that German forces facing them were very weak – a necessary prerequisite, since the 22nd Infantry was allotted a grossly overextended attack frontage three miles wide. In fact, this sector was defended by the 275th Infantry Division with about 6,500 troops, 106 artillery pieces, 23 antitank guns, and 21 assault guns.

The initial attempt by the 8th Infantry to advance through the woods on November 16 was an ominous repeat of the situation facing the 109th Infantry a month before. The Germans had mined the forward defense line and built up another set of wire entanglements. After failing to penetrate it the first day, a second attempt on November 17 resulted in 200 casualties in one battalion alone. As other units had learned from previous forest fighting, tank support, no matter how difficult to implement, was critical. On November 18, the 8th Infantry was supported by two platoons of light and medium tanks, which finally managed to blast away the obstructions. With armored support, the 8th Infantry was able to reach one of the few roads in the area.

GIs of the 3/8th Infantry, 4th Infantry Division move up the slopes of the Hürtgenwald along the River Wehe between Schevenhütte and Josawerk on November 18. (NARA)

A pair of M10 3in. GMC of the 803rd Tank Destroyer Battalion move up a forest trail near Josawerk in mid November while supporting the 4th Infantry Division in the fighting in the Hürtgenwald. (NARA)

Gen “Tubby” Barton, the 4th Division commander, seen here driving his jeep, confers with the commander of the 22nd Infantry, Col Charles Lanham, in mid September before the Hürtgen fighting. (NARA)

The 22nd Infantry’s zone of advance was far from ideal since there were no roads in the sector and the only hope of keeping the unit supplied would be to improve one of the firebreaks running through the forest – hardly an ideal situation in hilly, forested terrain already inundated with autumn rain. The regiment had to move through the ravine of the Weisser Weh then surmount the Rabenheck ridge. The regiment struggled for three days through the rugged terrain while encountering only an occasional German outpost. Casualties came from the numerous mines, which were especially thick along the firebreak trails, and from German artillery which already had most of the key firebreaks and crossing points zeroed in. In the first three days of the advance, the 22nd Infantry lost all three battalion commanders, half its company commanders and many other combat leaders.

In spite of the difficulties facing both regiments, by November 19 the advance appeared to be progressing steadily if slowly, and German resistance was weak. The German 7th Army reacted on the night of November 18/19, dispatching GR 1058 of the 344th VGD, and reinforcing the 275th Infantry Division positions around Grosshau. These new troops slowed the advance of the US 8th and 22nd Infantry regiments to a crawl on November 20. In the first five days of combat, both regiments had penetrated the forest to a depth of about a mile and a half but had suffered 1,500 casualties, with losses in combat leaders being especially grievous. Recognizing that the division could advance little further unless reinforced, the First Army ordered the V Corps to take over the entire Hürtgen sector and to commit another division, the 8th Infantry Division, from the positions being held by the 12th Infantry with the aim of taking the town of Hürtgen. In the meantime, the German 7th Army completed the relief of the battered 275th Infantry Division with the 344th VGD.

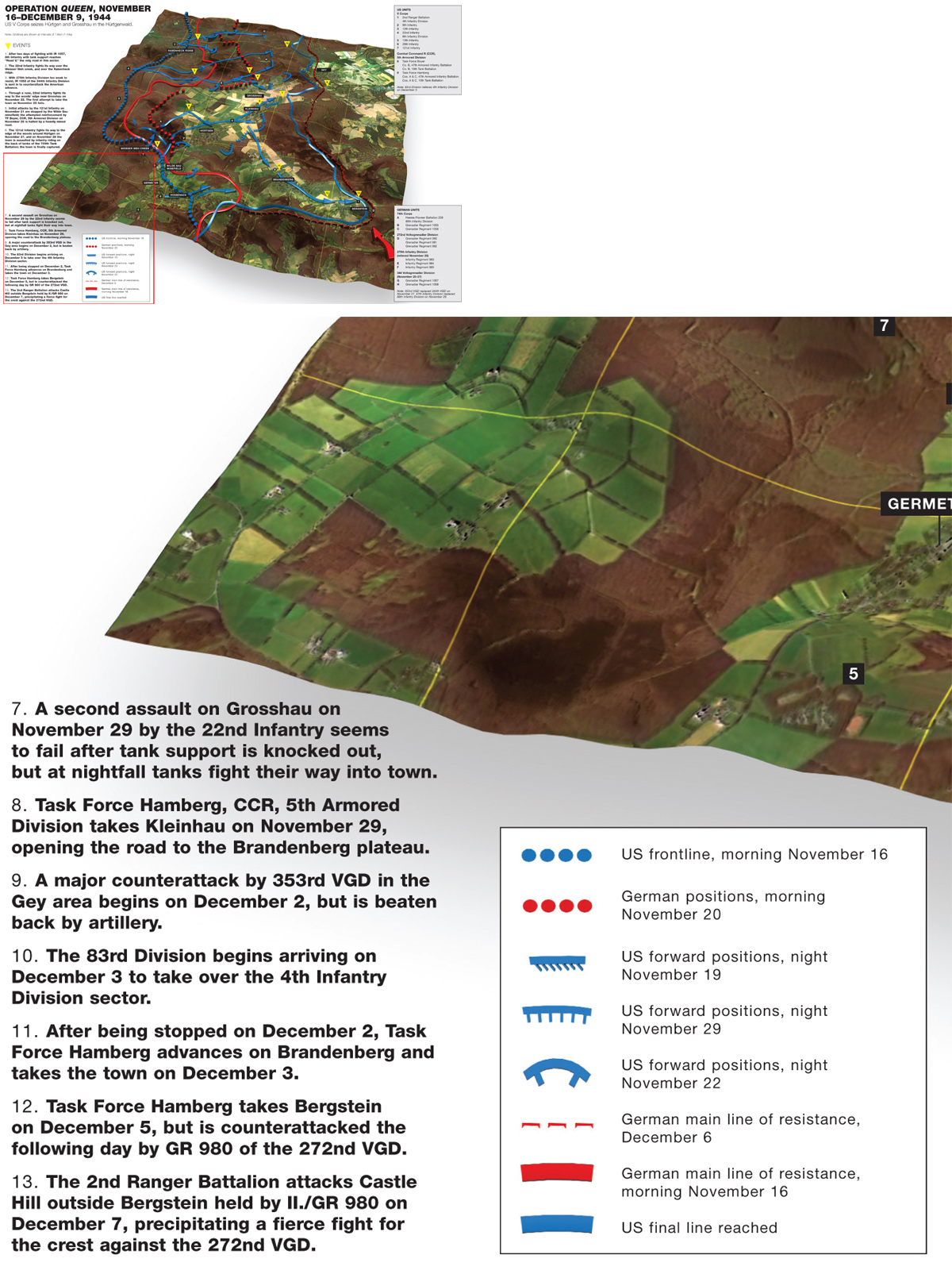

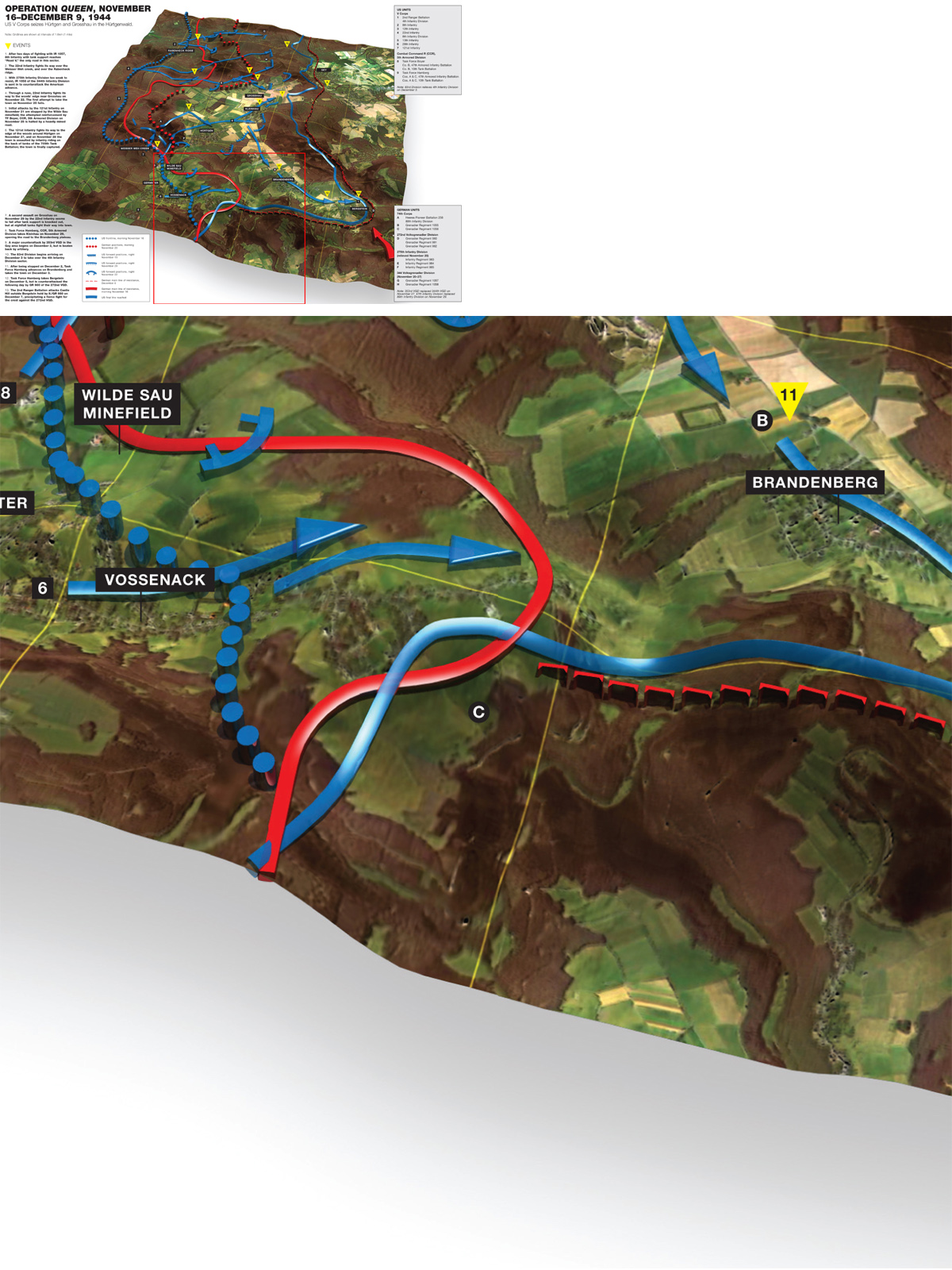

The commitment of the 8th Infantry Division complicated the 7th Army’s defense of the Hürtgen plateau, but the advance of the 4th Infantry Division remained slow. The 8th and 22nd Infantry finally reached the woods’ edge near Grosshau after employing deception. On November 22, two battalions pretended to stage an attack with gunfire, smoke and artillery support while safely ensconced in their log bunkers. This attracted the German artillery in abundance while three other battalions executed the actual attack. In spite of this small success, the first attempt by the 22nd Infantry to seize the town of Grosshau on November 25 failed due to the usual problems of co-ordinating infantry and armor support in the wretched forest conditions. The division ordered another lull to bring up elements of the 12th Infantry and to narrow the attack sectors of the two lead regiments. During the month, the 4th Infantry Division had needed 4,924 replacements – more than double the number of riflemen in the two attacking regiments. In the two weeks of fighting, some companies had gone through three or four company commanders; platoons were now commanded by sergeants and squads by privates. In spite of the appalling level of losses, the division continued to fight on. A renewed attack on Grosshau was forced on the division, ready or not, when the neighboring 8th Division to the south was attacking Kleinhau. The initial attack on November 29 faced the usual problems with tank support. The two tanks that did emerge out of the woods were knocked out by assault guns, two more were lost to mines, and the rest got stuck in the forest bogs or blocked by uncleared minefields. Shortly before dark, the situation abruptly changed as a flanking maneuver placed troops to the northeast of the town just as a group of tanks from the 70th Tank Battalion finally made their way out of the woods. Illuminated by the burning buildings, the town was cleared in house-to-house fighting.

A scene all too familiar in the Hürtgenwald. Medics attend to a wounded GI from the 8th Infantry, 4th Infantry Division during fighting on November 18, 1944. (NARA)

This 75mm PaK 40 antitank gun was positioned to cover the road outside Kleinhau, and was captured by the 8th Division in the late November 1944 fighting. (NARA)

Battery A, 18th Field Artillery Battalion fires a salvo of 4.5in. rockets during the fighting in the Hürtgenwald on November 26. This was the only rocket artillery battalion in the US Army at the time. (NARA)

Infantry of the 8th Division was finally able to break into the town of Hürtgen on November 28 riding on the back of M4 tanks of the attached 709th Tank Battalion, seen here in the ruins of Kirchstrasse. (NARA)

An 81mm mortar team from the 2/22nd Infantry, 4th Infantry Division fires in support of its battalion fighting in the woods near Grosshau, Germany on December 1. (NARA)

An M4 tank of CCR, 5th Armored Division takes up position on the northeast edge of Hürtgen prior to the renewal of the attack towards the Brandenberg–Bergstein plateau in early December 1944. (NARA)

The capture of Grosshau fundamentally altered the momentum of the attack since now the 4th Infantry Division could call on the support of CCA, 5th Armored Division to assist in the drive north along the open portions of the plateau. The timing was opportune as on December 2, the Germans launched a major counterattack from Gey, which was beaten back at the last minute by heavy artillery concentrations. By this stage of the fighting, the 4th Infantry Division commander, Gen Barton, turned to the VII Corps commander and frankly acknowledged that his division was in no shape to continue the offensive. In two weeks of combat, the division had suffered 4,053 battle casualties and over 2,000 non-battle casualties – more than twice the division’s allotted strength in riflemen. Collins ordered the division to stand down, and the 83rd Division began arriving on December 3 to finish the fighting in the forest. The 4th Infantry Division was transferred to a quiet sector of the front for rebuilding – the Ardennes – where it lay directly in the path of the upcoming German offensive.

While the 4th Infantry Division was conducting its final fight for Grosshau, the newly arrived 8th Infantry Division deployed two of its regiments in the Vossenack area. The burden of the task fell on the 121st Infantry, which was allotted the mission of pushing up the road to Hürtgen. The only difference this time compared with the previous debacles of the 109th and 12th Infantry was that the 121st Infantry was allotted a combat command from the 5th Armored Division to reinforce the attack once it penetrated the initial forward German defense lines. As should have been predicted, the attack by the 121st Infantry on November 21 was immediately stopped in the Wilde Sau minefield, which had been continually refreshed by German engineers. At the time, the 7th Army was able to concentrate about eight artillery battalions against the 121st Infantry, firing on average some 3,500 rounds a day. The regimental commander tried to prod the battalions along, relieving three company commanders in a few days. But after three bloody days, the 121st Infantry had failed to reach its objectives. An attempt by tanks of CCR, 5th Armored Division on the morning of November 25 was quickly halted by mines and antitank guns, and CCR withdrew until the road was cleared.

A German Maultier half-track being used as an ambulance was abandoned along the road from Kleinhau to Brandenberg during the advance of the 121st Infantry, 8th Division in early December. (NARA)

The 8th Division attack was renewed on November 26 after the 121st Infantry was reinforced by the 1/13th Infantry. While the US infantry had taken heavy casualties, US artillery had inflicted substantial losses on the German infantry as well. Within a day, the 121st Infantry had advanced to the woods on the western and southern side of Hürtgen. US infantry began attacking into the town of Hürtgen on November 27 while the German Fortress Machine-gun Battalion 31 continued to defend from the rubble. Finally on November 28, a company of infantry rushed the town, riding M4 tanks of the 709th Tank Battalion. House-to-house fighting ensued, but by the end of the day the town was finally in the hands of the 121st Infantry and 200 prisoners were rounded up.

With the road through Hürtgen finally clear, CCR, 5th Armored Division was ordered to try its hand against Kleinhau, the next town on the plateau, to coincide with the 4th Infantry Division attack on Grosshau. The weather permitted air strikes to supplement artillery bombardment of the town and the pilots reported that Kleinhau had been “practically destroyed by flames.” Although the shoulders of the road were mined, the Germans had not had time to mine the road itself, and Task Force Hamberg pushed into the town. German artillery was much less active than usual, as the clear weather allowed US fighter-bombers to operate and attack any active batteries. By the end of the day, the 10th Tank Battalion had established roadblocks on the other side of Kleinhau facing Grosshau. The cost to the 121st Infantry and attached units in nine days of fighting had been 1,247 casualties, but the Germans had lost 882 prisoners alone and had suffered substantial additional casualties.

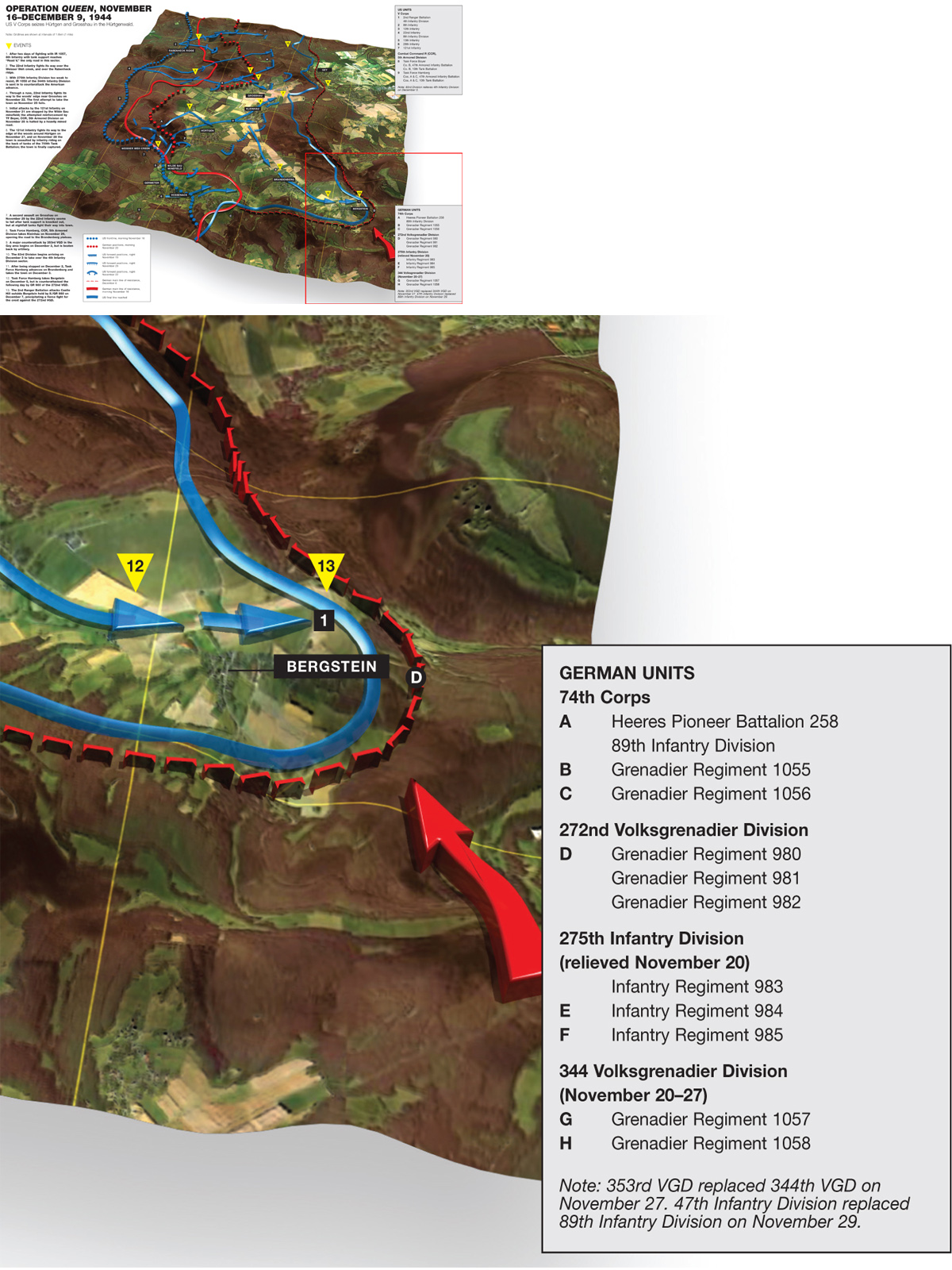

The importance of the capture of Kleinhau was that it opened up a route towards the Roer dams across the top of the plateau instead of through the woods beyond Vossenack. Rather than push north towards Düren, V Corps was ordered to proceed eastward to seize the Brandenberg–Bergstein ridge, which provided a good road network that cut across the northern neck of the Hürtgen forest. Task Force Hamberg set off down the road at dawn on December 2, but was quickly stopped by a minefield covered by German guns from the Kommerscheidt–Schmidt ridge above. The weather the next day intervened in favor of the Americans and so fighter-bombers were able to keep the German artillery suppressed; Brandenberg was captured before noon. Curiously enough, after the American P-47s left, the Luftwaffe made a rare appearance and about 60 Bf-109 fighters tried to strafe the town, but with little effect.