chapter 5

GETTING UNATTRACTED TO CONFLICT: THREE PRACTICES

RESOLVING INTRACTABLE CONFLICTS is never going to be quick or easy. But it doesn’t need to be impossible. It basically requires three things:

1. A good enough conceptual framework for understanding what’s going on.

2. A set of evidence-based practices for addressing the 5 percent.

3. A core set of skills for developing the capacity to employ the practices effectively.

The general objectives of the approach to 5 percent conflicts prescribed by the Attractor Landscape Model (ALM) differ fundamentally from the objectives of more standard models of constructive conflict resolution that are concerned with the other 95 percent of conflicts. The ALM does not aim to identify and satisfy underlying interests and needs in order to resolve the presenting conflict. Rather, the ALM looks to transform the dynamics of the system maintaining the status quo. Specifically, its objectives are to regain a sense of accuracy, agency, and possibility in the conflict; to achieve sustainable solutions by first opening up the closed system of the 5 percent to different information; and to then reconfigure the attractor landscape for the relationship.

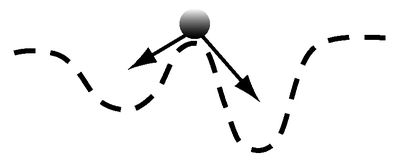

This is done by employing a set of practices aimed at constructively managing the current state of the conflict, while increasing the probabilities for constructive relations between the parties in the future

and decreasing the probabilities for destructive future encounters. This takes time.

fSTANDARD AND DYNAMICAL MODELS

| Problem-solving Model | Attractor Landscape Model |

|---|

| Assumptions | Assumptions |

| • | Short-term, outcome focus (agreements) | • | Dynamic, long-term change in patterns |

| • | Rational decisions | • | Emotional context of decisions |

| • | Linear change processes | • | Nonlinear dynamics |

| Orientation | Orientation |

| • | Identify presenting conflict issues and underlying needs | • | Map links and feedback loops between elements |

| Objectives | • | Identify actionable hubs |

| • | Satisfy underlying needs, resolve conflict | • | Visualize manifest and latent attractor landscape |

| Approach | |

| • | Conflict analysis, intervention, and | Objectives |

| agreement | • | Accuracy, agency, possibility, sustainability |

| Tools | • | Reconfigure attractor landscape |

| • | Problem solving, negotiation, mediation, | Approach |

| consensus building, compensation, logrolling, pressure, coercion | • | Case study (loop-mapping), visualization, address probabilities and read feedback |

| | Practices |

| • | Complicate to simplify |

| • | Build up and tear down |

| • | Change to stabilize |

THE PRACTICES

There are three basic practices for addressing the 5 percent constructively. These practices are all informed by the ALM model, principles and research presented in part 2 of the book. Together they constitute both an ancient and modern approach to conflict. Ancient in that they are rooted in thinking on complexity, coherence, dynamism, and conflict first presented by the Taoists in the third or fourth century BC. Modern because they are informed by contemporary research and methods in psychology and complexity science.

Like most everything associated with conflict, these practices involve tension and process. They are not tools or techniques for intervention. That would reflect linear cause-and-effect thinking. They are dialectical practices that incorporate the psychological principles of change, contradiction, and holism outlined in chapter 4.

1 They are ways of thinking and acting that can enhance our capacity for addressing the 5 percent and thereby increase the probability for constructive change. Each practice addresses basic contradictions:

complexity/simplicity, creation/destruction, and

change/stability, which are opposing human needs, tendencies, or processes.

2 At their core, the practices involve an iterative process of managing tension, contradiction, inconsistency, and change.

1. Complicate to simplify. This entails breaking through the press for coherence and oversimplification that is so forceful and constraining with the 5 percent, while attempting to identify the actionable hubs, gateways, and patterns otherwise disguised by the complexity of the conflict.

2. Build up and tear down. This is the practice of stirring or creating a sense of hope and possibility for more constructive relations in a conflict, while simultaneously deconstructing the traps for enmity and destruction that lie in wait to recapture the dynamics of the system.

3. Change to stabilize. This practice views adaptation and change as critical to stability and sustainability. It is about leveraging opportunities for change in a manner mindful of long-term dynamics and the need for adaptation in nonlinear systems.

ALL THREE PRACTICES WORK TOGETHER in a cyclical fashion. The first, complicate to simplify, constitutes a framework for conflict analysis and mapping; it can allow for new understandings and insights to emerge for addressing difficult conflicts. The second, build up and tear down, is the main category of strategic action; it involves an array of tactics, both old and new, for altering the conflict attractor landscape over time. The final practice, change to stabilize, highlights the importance of leveraging change and adapting effectively to changing circumstances in order to achieve sustainable solutions. Of course, any conflict could benefit from these practices. However, the 5 percent, which drag us, often unwittingly, into the depths of their attractors, require them.

What follows are more detailed discussions of each of the practices and their associated actions and skills. Whether or not you find value in any particular action for addressing conflict, remember it is the practices and the science behind the practices that really matter. This is what you should take with you and use as you see fit. In other words, think of these practices as the basic equipment you need when setting out on your own expedition to discover your 5 percent solution.

The Conflict in the Middle East—at Columbia University

For years, students in the Middle Eastern and Asian Languages and Cultures Department (MEALAC) at Columbia University had complained about what they saw as intimidation of Jewish students by pro-Palestinian professors in the department. The university, for a variety of reasons, had been generally unresponsive to these complaints. Everything changed when an Israeli advocacy group released a documentary film called Columbia Unbecoming, presenting student testimonials alleging incidents of academic abuse and intimidation by MEALAC faculty.

Students flocked to see the film in which several professors were identified by name. The testimonials claimed that Jewish students had been mocked and marginalized by these and other “pro-Palestinian” Columbia professors. The faculty members implicated in the film denied the allegations, but nevertheless events escalated.

The accusations grew, from initial complaints about the actions of a few professors at MEALAC, to claims of pervasive bias in the university curriculum and a general anti-Israeli and pro-Palestinian culture among university faculty. The debate also spread to the news and editorial pages of several newspapers and to the blogs of several prominent Israeli and Palestinian commentators. The New York Daily News published a special report headlined “Poison Ivy: Climate of Hate Rocks Columbia University.” It stated: “Dozens of academics are said to be promoting an I-hate-Israel agenda, embracing the ugliest of Arab propaganda, and teaching that Zionism is the root of all evil in the Mideast.” In response, one of the implicated faculty responded by writing: “This witch-hunt aims to stifle pluralism, academic freedom, and the freedom of expression on university campuses in order to ensure that only one opinion is permitted, that of uncritical support for the state of Israel.”

Columbia’s president, Lee Bollinger, responded by establishing a high-level faculty committee to investigate the claims of bias put forth in the film. But members of a student group immediately protested this move. They charged that the committee itself was biased because of personal and professional connections to the implicated professors, and due to some of the committee members’ own prior anti-Israeli statements. Nevertheless, the committee continued its investigation and tensions spread. One of the professors named in the film abandoned his signature course for that term for fear of reprisals (he was pre-tenure). There were several instances of nonenrolled hecklers attending the implicated faculties’ courses, and insults and death threats were left on their answering machines. It was also reported that the conflict began affecting alumni funding and student admissions. Then the Israeli ambassador to the United Sates withdrew under protest from an international conference scheduled to take place at Columbia.

When the faculty committee released its report, it issued a harsh condemnation of university grievance procedures, but offered little clarity on the many other issues linked to the dispute. While the report was clear on the need to reform grievance processes, the initial allegations of bias and intimidation remained unresolved, and the student, faculty, and public response was indignant. The controversy has continued for years. It has been particularly contentious around tenure decisions for the implicated faculty, and around related issues of classroom behavior and the limits of academic freedom. Further, the conflict was touted by some as merely one example of a problem that festered at many other campuses as well, and the filmmakers expressed their intention to release new documentaries made at other colleges and universities.

PRACTICE I: COMPLICATE TO SIMPLIFY

Imagine you are the president of Columbia University when the exposé documentary Columbia Unbecoming premieres at Columbia’s Lerner Cinema, accusing your university of flagrant anti-Semitism. Within minutes the calls and emails start flooding in. Angry parents, furious faculty, student activists, the media, bloggers, the mayor of New York City, the New York Civil Liberties Union, alumni donors, members of your own family, you name it, call and demand action. But of course the actions they demand are all over the map, extreme, and often in direct contradiction to one another, or completely irrelevant to the issues as you see them. The pressure on you to act decisively is extraordinary.

Alternately, imagine that you are one of the students at Columbia. You feel you were publicly humiliated by a faculty member for asking a straightforward question in class. You were thrown out of class and later told by your peers that your professor called you a “Jewish spy.” Said professor then reportedly went on a “paranoid rant” about people like you. And you know all too well that this is not an isolated incident. Other students have been treated this way by Columbia professors and subsequently complained to the university. Yet they got a less than satisfactory response from the administration. You are also aware that this is happening not only at Columbia, but at other colleges and universities as well.

Or imagine that you are one of the accused faculty members implicated in the MEALAC case at Columbia. For years now, despite being cleared of any wrongdoing by the university’s investigatory panel, every paper you publish, every comment you make, every glance toward a student, even the things you do not say are scrutinized, documented, and taken as more evidence of your obvious anti-Semitism. You know that a well-organized network of pro-Israel activists outside the university is working tirelessly against you; manufacturing falsehoods, inflaming opinions, and lying in wait for you to misspeak.

What’s a disputant to do?

The attractor has you. You are now lying on your back at the bottom of a wide and deep crevice of conflict. Whether you are the beleaguered university president, or the aggrieved student, or the accused faculty member in this scenario matters, of course. But everyone is now constrained and controlled by a powerful constellation of mostly unseen forces.

Of course, our natural impulse in these situations is to fight or flee. To lash out, blame, attack, or challenge someone, or otherwise try to get out and avoid the situation altogether. These responses make perfect sense in the short term, but likely will have little effect on the 5 percent. In fact, they may make matters worse in the long term.

So if escaping or resolving this conflict is your goal (and we do not assume this is always the case), we suggest a different approach. And it begins with complicating your life.

CONFLICT-MAPPING 1: COMPLICATE THINGS

See the System

When you find yourself stuck in an oversimplified polarized conflict, a useful first step is to try to become more aware of the system as a whole: to provide more context to your understanding of the terrain in which the stakeholders are embedded, whether they are disputants, mediators, negotiators, lawyers, or other third parties. This can help you to see the forest and the trees; it is a critical step toward regaining some sense of accuracy, agency, possibility, and control in the situation.

At the moment, the 5 percent conflict is in charge. It is shaping what you and others see, think, feel, and do. So it is important to first regain some sense of accuracy in your perceptions. This is not easy. It is swimming upstream against what you and others in the conflict feel to be certain. However, because of the dramatic pull of the 5 percent attractor, achieving a better sense of the different independent but interrelated elements of the conflict is an essential fist step. As Columbia president Lee Bollinger stated at the time of the MEALAC crisis, “Many people, perhaps understandably, do not grasp what’s at stake. They see one side of it, one aspect of it. This can’t be reduced to a single line of thought.”

3Recall that the collapse of complexity that accompanies 5 percent conflicts happens along many dimensions:

• A very complicated situation becomes very simple.

• A focus on concrete details in the conflict shifts to matters of general abstract principle.

• Concerns over obtaining accurate information regarding substantive issues transform into concerns over defending one’s identity, ideology, and values.

• The out-group, which was seen as made up of many different types of individuals; now are all alike.

• The in-group, which was seen as made up of many different types of individuals; now are all similar.

• Whereas I once held many contradictions within myself in terms of what I valued, thought, and did; now I am always consistent in this conflict.

• Whereas I used to feel different things about this conflict—good, bad, and ambivalent; now I feel only an overwhelming sense of enmity and hate.

• I’ve shifted from long-term thinking and planning toward short-term reactions and concerns.

• Where I once had many action options available to me, I now have one: attack.

This is the bad news about the 5 percent, but it’s also the good news. The collapse of complexity occurs on so many levels, all leading a similar state of “us versus them” thinking, that reintroducing a sense of complexity and agency can also be achieved in a wide variety of ways. There are therefore many places to find points of leverage to rupture the certainty and oversimplification that rules in these situations.

The question is how to find them.

Most standard approaches to conflict analysis begin with making lists for this very purpose. They start with a negotiator, lawyer, mediator, or other third party who listens to the disputants, identifies the main issues, lists them on a piece of paper, prioritizes them, and then gets to work. This is exactly how I was trained by the New York State criminal courts to be a community mediator. The standard lists look like this.

| UNIVERSITY ADMINISTRATION | UNIVERSITY STUDENT |

|---|

| Inflammatory accusations | Public humiliation |

| Importance of free speech | Importance of free speech |

| Protection of CU’s reputation | Protection of personal reputation |

| Respect grievance procedures | Unresponsive procedures |

| Faculty’s and students’ rights | Students’ rights |

| The plight of Palestinians and Israelis | The plight of Israelis |

Although listing issues can be a useful tool for organizing the discussion, and has proven helpful with many types of disputes, it presents two problems in addressing the 5 percent.

Problem 1: Subjectivity, bias, and spoilers. Analyzing conflicts is an

active cognitive process where the analyst perceives, interprets, shapes, and articulates the pattern of events in question. This flies in the face of traditional notions of third-party

neutrality and

objective fact-finding in conflict resolution, which are pervasive in the field today.

4

Typically during analysis, conflict interveners make a set of critical choices, often under severe constraints, which help determine the future pattern of conflicts. For instance, if invited to intervene in the Columbia University conflict, we would typically have a say in determining which stakeholders, out of the multitude of possibilities, are especially relevant to the conflict and therefore need to be included in assessment and resolution processes.

Immediately, several questions arise. Shall we work with key group representatives or with all stakeholders in a large-scale consensus-building process? Shall we involve more radical agitators inside and outside the university community, or focus on mainstream insiders with broad spheres of influence? These are often necessary and practical choices that carry powerful symbolism; they signal which parties are legitimate and central and which are not. This legitimization can ultimately contribute to the unintentional development of “spoilers”: parties who become motivated to undermine what they perceive to be an exclusive and misguided peace process.

5A similar process occurs when identifying and prioritizing the issues and grievances in a conflict. As certain problems gain in salience (such as concerns over the university’s grievance procedures), they tend to capture the attention of the intervener and main stakeholders, often at the expense of other issues. Over time the neglected issues and parties can regain importance and challenge the integrity of prior agreements. (This, incidentally, is what many believe led to the collapse of the Oslo Accords in the Middle East conflict.)

The point is that the choices interveners first make help to set the initial conditions and subsequent pattern of conflicts.

Problem 2: Linearity and premature simplification. The second problem with using simple lists of issues as a way of organizing the conflict resolution process is that it once again compares fluid things to fixed things. It typically involves a process of listening to complex, contradictory stories—multiple, nuanced, subjective narratives of ongoing escalatory dynamics—and then using terms or short phrases to capture the main points.

So what is an alternative? Loops.

Conflict Feedback Loop–Mapping

Rather than making lists, it can be fruitful to sketch the evolving system of 5 percent conflicts through a series of feedback loop analyses. Loop analysis was developed decades ago by the mathematician and cultural epistemologist Magorah Maruyama.

6 It is particularly useful for mapping different aspects of a conflict and identifying reinforcing and inhibiting feedback loops that contribute to the escalation, deescalation, and stabilization of destructive conflicts.

This method not only helps to recontextualize our understanding of a conflict, but also helps to identify central hubs and patterns in the conflict unrecognizable by other means. This is achieved by capturing the multiple sources, links, and complex temporal dynamics of such systems.

Mapping any of these aspects of an evolving conflict can help to tease out and disentangle the morass of grievances and misperceptions that make up the coherent and oversimplified world of the 5 percent. It can help to simply take the time to see how complex these problems can become, which is one reason mapping is used increasingly by conflict practitioners working on the ground in complicated situations.

However, I must offer one caution. It is very important when using a conflict-mapping methodology that everyone involved be clear about the degree of objectivity versus subjectivity of the exercise, and of whatever elements are being mapped. This can be thought of along a continuum.

OBJECTIVE-SUBJECTIVE CONTINUUM

| Objective | Subjective |

|---|

| (Externally verifiable elements of conflict) | (Psychologically perceived elements of a conflict) |

Mapping Objective Structures. On one end of the continuum are conflict maps that can be generated of actual, empirically verifiable entities, structures, processes, and events. For example, the communications networks—phone traffic, email correspondence, Internet traffic, physical visits together and time spent speaking—of disputants and stakeholders in a conflict setting could be mapped, as could the physical locations of events, such as crimes or conflictual encounters or group violence. These maps can employ sophisticated network analysis and visualization tools; they can be very helpful in visualizing temporal and spatial patterns of relationships and events. This type of mapping is less common in the conflict and peace field today (with the exception of police and peacekeeping activities, disaster relief, and covert intelligence gathering), but its use is increasing in emergency situations. For example, humanitarian observers of the political violence in Kenya in 2009 used GPS tracking of cell phone data from hundreds of locals to pinpoint and communicate the location of hotspots of political violence.

CONFLICT MAPS ARE VERSATILE TOOLS

A variety of different aspects of conflict can be mapped.

• People and social networks. How allies and opponents relate to one another in conflict situations. Who talks to whom in the conflict? Who avoids whom? Are there possible communication links through various parties for linking negotiations between key adversaries? Are the social networks stable or changing over time?

• Cultural beliefs, social norms, and community institutions. How macro elements of the conflict work together or against one another to perpetuate destructive (or constructive) intergroup relations. For example, how group beliefs in the utility of violence, political rhetoric about past atrocities committed by the out-group, cultural norms dictating distrust of outsiders, school curricula that present biased historical accounts of a conflict, and the presence of rituals and monuments honoring slain warriors operate together to reinforce the need for ongoing group struggle. Or alternatively how strong advocates for human rights, a free press, an attentive and responsive international community, and an impartial judiciary system can operate to inhibit destructive dynamics.

•

Issues, needs, and interests. How the different concerns and goals of the disputants relate to one another. Are they a set of relatively unrelated and loosely coupled issues, or a tight constellation of needs and interests? Which issues are more basic and pivotal to each party? Are these concerns shared by different stakeholders? Have the primary concerns shifted in importance over time?

7 • Visions, hopes, and dreams. What does an ideal solution to this conflict look like for each stakeholder group? What are the activities, events, and structures they would like to see in place that would help resolve the conflict and sustain more tolerant or constructive relations? How do the different stakeholder maps compare and contrast? What potential problems or unexpected consequences may result from these activities, events, and structures?

• Individual thoughts, feelings, and actions. How different aspects of any individual stakeholder’s experience of the conflict link together and collapse into a coherent attractor or not. These aspects may include its past history, perceptions of the in-group and out-group, feelings of loss, guilt, and so on. Where are the strongest and weakest links?

And most important:

• A chronology of events. How a series of events transpired over time to increase the intensity and destructiveness of a conflict to maintain it in its current state and/or to deescalate it. What are the specific events? When did they occur? How did they reinforce or inhibit the escalation, stalemate, or deescalation of the conflict? Did any elements in fact do both: escalate and deescalate the conflict simultaneously or over time?

Mapping Subjective Aspects of Conflict. On the other end of the spectrum, conflict maps can also be generated of disputants’ and other stakeholders’ perceptions of relevant parties, issues, norms, institutions, etc. in a conflict. This is typically known as concept-mapping or mind-mapping. It is an excellent exercise for unearthing assumptions, perceptions, and misperceptions in understanding; for providing context and nuance to the perceiver’s sense of a conflict; for exploring temporal dynamics in people’s understanding of the chronology of events; and for identifying areas of shared or contradictory meaning for different stakeholders.

This more subjective version of conflict-mapping is used more frequently by peace practitioners today. However, even though this exercise can generate complex conceptual maps of important and relevant aspects of a conflict, and show the reinforcing and inhibiting links between these elements, it must be understood to be a purely subjective tool. These maps are not maps of external structures or of objective facts; they are simply expressions of each individual’s or group’s perception of what has transpired in the conflict, which is typically biased in the 5 percent.

This distinction is not meant to devalue subjective conflict-mapping; on the contrary, it can be immensely useful. However, it is important to be clear that there are significant differences between the value and utility of more objective conflict-mapping exercises and more subjective mapping processes.

This is one reason why we recommend beginning with stakeholder mapping of the chronology of events of the 5 percent. Although the reason why particular events occurred is often hotly disputed in 5 percent conflicts, the facts of where, when, and sometimes how they occurred are usually somewhat less so. That means that conflict event chronology-mapping falls somewhere between purely objective (fact finding) and purely subjective (perceptions, memories, and interpretation) exercises. This is because some events will be documented formally and may be easier to agree upon (for example, Columbia Unbecoming had its first public showing on Columbia’s campus on Friday, January 18, 2003), while others may be much more ambiguous and contested. Thus, event chronologies are usually good starting points for stakeholder mapping. They can help disputants unpack and visually express their shared and contradictory understanding of the history of events and of how each event may have affected the next set of events.

Conflict Event-Mapping: Four Steps. The process of event-mapping involves four basic steps.

Step 1: The stakeholders clarify which dynamic they are trying to understand. Do they want to know why a conflict escalated so quickly and so aggressively? Do they want to understand why the conflict is stuck and has remained at a stalemate for years (key to the 5 percent)? Or do they want to understand why the conflict seems to follow a periodic pattern of escalation and deescalation over time without ever really changing course? This point of focus must be defined at the start of the exercise, as each of these dynamics may require mapping somewhat different aspects of the conflict.

Step 2: The stakeholders identify the chronology of events relevant to the dynamic of interest, as far back as they feel is important, leading up to the present circumstances. Again, what is seen as “relevant” will be determined subjectively by each stakeholder involved and by the specific focus of the exercise (mapping escalation, stalemate, periodicity, etc.). We suggest this step first be conducted with independent stakeholders or small constituent groups; in-group differences in perceptions and values can then be explored before moving on to compare and contrast maps with members of out-groups.

Step 3: The stakeholders begin to map and connect the different events in chronological order. They use two criteria: (1) how each event triggers, feeds, or reinforces other events in such a way that more leads to more, or less leads to less (reinforcing feedback), and (2) how each event constrains, inhibits, or reverses other events so that changes in one direction are associated with changes in the opposite direction (inhibiting feedback). This activity can be done most simply using flip-chart paper or a whiteboard, or by using PowerPoint or any simple concept-mapping software available online, like Mindjet or iMindMap.

Step 4: Once the event maps are drafted, we have several options. One option is to work with each individual stakeholder or group to explore their map; we identify missing elements and links, surprising connections, and generally work to enhance the diversity and complexity of their understanding of the conflict. A second option is to compare maps across stakeholder groups with the expressed goal of thinking different, of seeing the conflict from a fresh point of view. A third option is to go on to the next phase of practice 1, which is to simplify things before engaging stakeholder comparisons or discussions.

Conflict Event-Mapping: An Illustration. Below we illustrate this exercise by walking through a preliminary subjective event-mapping of the exponential escalation of the Columbia University MEALAC case over five phases of its escalation. These events were compiled from several newspaper accounts and personal communications.

8

Phase 1: The MEALAC conflict at Columbia seemed to escalate quite rapidly in 2002–2003. Whether or not it was a coincidence, reports of bias and abuse at MEALAC first surfaced around the time of the intensification of the second intifada in Israel; they also came in the wake of a quashed movement by students and faculty at Columbia to divest from companies that manufactured and sold weaponry to Israel. The MEALAC department had been formally constituted at Columbia in 1965 and some of the accused faculty had been there for decades. However, the 2001–2002 escalation of events in the Israel-Palestine region may have triggered past traumas, resentments, or guilt of Columbia faculty and students, contributing to their actions at this time.

Events probably went like this. Reports of discriminatory behavior at MEALAC became associated with reports of similar acts of bias at other universities (for example, at the University of Chicago in 2002). The existing grievance procedures at Columbia offered a limited response to the grievances. The sense of outrage among students intensified. At this point members of Columbia’s LionsPAC student organization were likely motivated to approach the David Project, a pro-Israeli advocacy group. The film Columbia Unbecoming was conceived, setting the stage for escalation. Note how all the mapped events are connected by reinforcing links, with no inhibiting loops to slow things down. This contributed to the rapid escalation of the conflict on and around campus.

TEMPORAL PHASE

Initial Phase of the MEALAC Conflict at Columbia

Phase 2: In December 2003, the David Project released Columbia Unbecoming, which presented student testimonials of academic abuse and intimidation in MEALAC. The documentary named three professors: George Saliba, Hamid Dabashi, and Joseph Massad. Students claimed that in recent years they had felt mocked and marginalized by these and other “pro-Palestinian” professors. Two allegations received the most attention. One involved a sidewalk encounter between a former student and her professor at the time, Saliba. The student claimed that Saliba told her that because she had green eyes, she was not a Semite and could therefore not claim ancestral ties to Israel. The second allegation was made by a student who had served in the Israeli army. He said that when he tried to question Massad during an off-campus lecture, the professor responded by asking him, “How many Palestinians have you killed?” The implicated faculty members denied the accusations. The allegations became officially public in October 2004, when Barnard College president Judith Shapiro referenced the film in a speech at an alumni event.

These events began to link together, reinforcing one another in the minds and conversations of the Columbia community and beyond. They intensified the conflict, connecting directly with peoples’ varied experiences of the long and troubled history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. During phase 2, once again no significant events that served to dampen the escalation of tensions were identified.

Phase 3: Soon after President Shapiro’s comments, the New York Sun printed the first of many inflammatory articles about the events at Columbia; within two weeks hundreds of students packed Columbia’s Lerner Cinema to view the film. Then, early in December 2004, a group of fifty students, faculty, alumni, and community members held a press conference to protest what they felt was the stifling of voices critical of Israel. This group, the Ad Hoc Committee for the Defense of Academic Freedom at Columbia, accused the university of failing to protect freedom of speech; it also accused the David Project of misrepresenting facts. These accusations may have lessened the escalatory impact of Columbia Unbecoming by questioning its legitimacy (a rare inhibitory link), but they also sparked increased tension and controversy evident in editorials and blogs (which served as reinforcing loops).

TEMPORAL PHASES

Phases 1 to 2 of the MEALAC Conflict

Events swiftly escalated further. Accusations expanded to include claims of anti-Israeli bias in the MEALAC curriculum and a general anti-Israeli, pro-Palestinian bias among the entire Columbia faculty. The debate continued to spread through the news and editorial pages of several newspapers and to the websites of several prominent pro-Israeli and pro-Palestinian commentators. The New York Civil Liberties Union and the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education issued strongly worded statements.

It wasn’t just the media—things were becoming personal. One professor in Columbia’s medical school sent an email to Professor Massad, saying “Go back to Arab land where Jew hating is condoned. Get the hell out of America. You are a disgrace and a pathetic typical Arab liar.”

9 Professor Massad was compelled to abandon one of his signature courses, Palestinian and Israeli Politics and Societies, that spring term. There were several instances of classroom heckling, and insults and death threats were leveled at the faculty. Concerns that the conflict would affect Columbia’s alumni funding and student admissions arose.

Phase 4: On December 8, 2004, Columbia president Lee Bollinger responded to the controversy by announcing the creation of a high-level faculty ad hoc committee to investigate the claims of bias put forth in Columbia Unbecoming. This strategy might have temporarily mitigated the conflict. However, members of a student group then sent a letter to Bollinger charging that the ad hoc committee was itself biased: there were alleged personal and professional connections among members of the committee and some of the implicated professors from MEALAC, and some of the committee members had allegedly made anti-Israeli statements. For instance, one committee member had advised Professor Massad on his PhD thesis, and two others had signed the 2002 divestment petition demanding that Columbia withdraw economic support from Israel. This sparked even more outrage. Nevertheless, the committee proceeded as originally constituted, hearing testimony and deliberating for two months. Then in January 2005, in response to the controversy, the Israeli ambassador to the United Sates, Daniel Ayalon, withdrew from an international conference scheduled to take place at Columbia.

TEMPORAL PHASES

Phases 1 to 3 of the MEALAC Conflict

On March 31, 2005, the ad hoc committee released its conclusions in a twenty-four-page report, issuing a harsh condemnation of Columbia’s grievance procedures but offering little clarity on the many other issues in dispute. The report stated that, for years, students’ complaints about Middle East studies professors in MEALAC had been ignored or mishandled. In this climate, the report continued, the complaints festered and the department became riddled with “suspicion, incivility, and an unhealthy, highly politicized atmosphere.”

10 The report also said that the committee found no evidence of anti-Semitism, although it did find that Professor Massad had on one occasion violated “standard norms of acceptable professorial conduct.”

11 The report served to validate many of the complainants’ concerns (reinforcing loop) and ameliorate some of the due process issues (inhibiting loop). However, it was seen as an insufficient response by many (once again, a conflict-reinforcing loop).

Phase 5: In April 2005, a group of students claiming they were in Professor Massad’s class on the day of the alleged misconduct wrote a letter denying the incident had taken place. Also in April, the

New York Times editorial board wrote that Columbia had “botched” the investigation by involving professors on the panel who were perceived as biased; it also accused Columbia of limiting the committee’s mandate so narrowly as to constrain the implications of its findings.

12 President Bollinger was assailed by some faculty members for defending the rights of professors too weakly and failing to contain the controversy. All these are conflict-reinforcing elements. Mr. Bollinger responded by saying that he found the dispute “very painful”

13 and that he was trying to protect both faculty and student rights.

TEMPORAL PHASES

Phases 1 to 4 of the MEALAC Conflict

In the midst of the controversy, despite campus programs like Turath’s and LionsPAC’s joint Project Tolerance and an announced million-dollar grant to start dialogue to increase multicultural awareness (inhibiting feedback loops), the campus remained divided. While the ad hoc committee’s report brought a measure of closure to the need to reform Columbia’s grievance procedures, the initial allegations of bias and intimidation remained unresolved. The accused MEALAC professors all took leaves of absence in 2005–2006. High faculty turnover and a climate of cautiousness and gloom reportedly continued to mark the department. One student called the professors’ absence “a brilliant political move” and remarked, “People are naive if they think we’re just going to kind of let things lie.”

14The MEALAC controversy continued for years and is likely latent today. At times it has become particularly contentious over tenure decisions regarding one of the implicated faculty members and around related issues of classroom behavior and the limits of academic freedom. As mentioned, the controversy at Columbia is regarded by some as only one example of a problem that festers on many other college and university campuses.

AS THIS EXERCISE ILLUSTRATES, conflict event-mapping allows us to begin to capture how a complex set of events in a conflict unfolds over time. We can then see how this set acts in concert to trigger and reinforce other events and/or to constrain and inhibit other events. It all works together to escalate, perpetuate, or deescalate conflict. These maps can be generated alone as a prenegotiation exercise (with minimal training), with the help of facilitators or mediators, or in small groups of stakeholders. Again, with concept-mapping the goal is not necessarily to get it right. The goal at this stage is to get it different: to try to reintroduce a sense of nuance and complexity into the stakeholders’ understanding of the conflict. The goal is to try to open up the system: to provide opportunities to explore and develop multiple perspectives, emotions, ideas, narratives, and identities and foster an increased sense of emotional and behavioral flexibility. To rediscover a sense of possibility.

TEMPORAL PHASES

Phases 1 to 5 of the MEALAC Conflict

A note to third parties: It is important for the conflict specialist to be mindful of her or his own dominant frames when helping to construct these maps. Which perspectives does the specialist tend to use and not use, and is anything important missing? A political scientist might focus primarily on what roles politics and power play in establishing the current attractor at MEALAC. To what degree is Columbia being played as a pawn by external political groups to bring attention to their cause? Are internal groups playing up ethnic differences to mobilize altogether different agendas?

Alternatively, a social psychologist would likely emphasize how social conditions on campus contribute to malignant relations between groups such that they maintain the problem. Given that some Jewish and Arab faculty and students may have been raised to hate, fear, and suspect the other, has Columbia done enough to establish conditions for respectful tolerance and dialogue on campus? Specialists with training in communications or linguistics might emphasize meaning-construction around the events, suggesting that we pay special attention to the stories being told about MEALAC in newspapers, official documents, and coffee houses on campus. Those trained in epidemiology might focus on the often overlooked roles that the individual and collective trauma of Israeli and Palestinian faculty and students, exacerbated by current threats of violence, play in the unfolding patterns at Columbia. How does past exposure to atrocities and human suffering affect their current responses to the situation at Columbia?

Of course, any of these perspectives on the problems at Columbia may be accurate and useful. That’s not the point. The issue is that they are all aspectual; they focus attention on some aspects of the problem and away from others. So whatever their training, it is often helpful for specialists to actively seek out varied and contradictory sources of information, to aim for increased accuracy in their understanding, and to try hold the temptation for premature simplification at bay.

In summary, complexity matters. And learning to effectively map 5 percent conflicts is one approach to capturing their complexity. It requires us to both see the problems in new ways and to attend to aspects of the problems we are not used to seeing. Of course, the degree of complexity of 5 percent conflicts defies comprehensive analysis. But that is not the objective of practice 1. Feedback loop–mapping can allow contextualization, discovery, and insight to emerge; our sense of the issues and events in a conflict can take on new meaning when seen from such a “field” or relational perspective. These exercises also highlight the value of cross-disciplinary collaboration; we need distinctly trained individuals working together with stakeholders in these settings in order to better comprehend the problem sets, both specifically and systemically.

CONFLICT-MAPPING 2: SIMPLIFY THINGS

Help!!!

In early 2010, NBC reporter Richard Engel uncovered a wildly complicated PowerPoint map depicting U.S. strategy to increase popular support for the Afghan government. It involved over 100 elements, each with multiple links or loops to other nodes. It was characteristic of the U.S. military’s current approach to counterinsurgency and what some officers refer to as a “fur ball.” Upon first seeing the map, General Stanley A. McChrystal, leader of American and NATO forces in Afghanistan at the time, remarked, “When we understand that slide, we’ll have won the war.”

15At the heart of much of what we’ve discussed so far is the double-edged sword of complexity. If the story of a conflict has lost complexity and become overly simplistic and polarized, we must reintroduce nuance into our understanding of the situation. But adding too much complexity can easily make an already complicated situation overwhelming, even immobilizing. Or it can lead to increased resistance and an even stronger push to oversimplify and choose sides.

It’s vital to employ a few general tactics for

managing complexity. This will permit us to see both the forest and the (more important) trees in the 5 percent. Each tactic is informed by our model and in particular by the approach of

dynamical minimalism, whose goal is to make use of the complexity of a problem in order to find the minimal set of mechanisms that can account for its evolving pattern, its character. Once again, the goal of dynamical minimalism is

simplicity informed by complexity.16In this section we outline five actions for harnessing the complexity generated in phase 1 of conflict-mapping; they will help us to develop more focused strategies and insights for understanding and leveraging change in 5 percent conflicts. They are (1) identify hubs, loops, and energy in the system, (2) identify local actionables, (3) locate what is already working, (4) identify integrative agents, and (5) visualize the attractor landscape.

1. Identify hubs, loops, and energy in the system. Once you sufficiently map a conflict system, you can begin to employ basic ideas and tools of network analysis to further explore the dynamics. Network analysis comes from work on network theory and has applications in areas of study including particle physics, computer science, biology, economics, operations research, and sociology.

Formal network analysis tools are most appropriate for conflict maps of a more objective nature: mapping communications networks, social networks, formal authority structures, and so on. However, the feedbackloop structure of subjective concept maps can also benefit from the application of network analysis tools. This is especially true when the maps have been generated and therefore validated by different stakeholder groups representing diverse points of view on the conflict.

There is value in focusing in on a variety of different aspects of conflict maps. For example: identifying central hubs of activity, elements that link with many other elements; key reinforcing loops, elements that stimulate themselves through links with other elements in an ongoing fashion; and the ratio, or balance, between conflict-reinforcing and -inhibiting feedback, which can determine whether a conflict is escalating, deescalating, or stuck in a stalemate.

Or you can look to see differences in levels of

in-degree of different conflict elements, as in how many links feed into each element;

outdegree, which elements serve as key sources of stimulation or inhibition in the conflict for other elements; and

betweenness, which describes the degree to which elements are located between and therefore link other elements. These are all useful lenses that can focus our attention and clarify our understanding of complex maps.

17Identifying central hubs and strong feedback loops in the system is particularly important for locating centers of energy in the system, gateways for high-impact intervention, strategic targets for introducing conflict-inhibiting feedback (such as early-warning systems that deter escalation), and peace-reinforcing feedback (like high-stakes common interests that motivate reconciliation). They also help to focus the analysis of conflict-mapping and to manage the anxiety associated with the overwhelming sense of complexity of the system. However, they do so in a manner informed by its complexity.

In mapping our analysis of the Columbia conflict, I highlight the reinforcing feedback loops that operate to intensify the conflict in an ongoing fashion (with solid lines) to illustrate two reinforcing loops: one between the reporting of acts of bias and the ineffective grievance procedures, and the other between the reporting of bias and the high level of turnover and dysfunctional work climate in the department at the time of the analysis.

When students’ complaints about bias at MEALAC were left unaddressed by officials at Columbia, it fostered student resentment and hypersensitivity to future abuses at MEALAC, leading to more complaints to the university, which when neglected increased resentment and so on. This is a conflict-reinforcing loop.

Similarly, word of the complaints of bias at MEALAC negatively affected the morale and work climate in the department, which led to higher turnover of experienced faculty and staff, resulting in fewer well-trained personnel and therefore a higher potential for student dissatisfaction, leading to more complaints against MEALAC and so on. Another loop.

Alternatively, I use dashed lines to highlight the various sources of inhibiting feedback operating to lessen the intensity of the conflict in the system. This map would be of particular interest to those invested in deescalating tensions and maintaining relative calm on campus. (Of course, it might be equally interesting to activists, anarchists, and other agitators interested in fanning the fires at Columbia as well.) This focus can help identify the current sources of conflict-inhibiting feedback as well as possible targets for introducing new sources.

For instance, strongly worded statements issued by the New York Civil Liberties Union and the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education challenging the accuracy of the accusations made in Columbia Unbecoming and in the New York Daily News reporting, contributed to an easing of the initial hysteria triggered by the film. The press conference held by the Ad Hoc Academic Freedom Group had a similar impact. Of course, the investigatory panel’s report helped mitigate tensions over the ineffectiveness of grievance procedures at Columbia, but it triggered other concerns due to the narrow nature of its mandate and findings. Most important, ongoing initiatives like the Joint Project on Tolerance and the campus dialogue project likely provided the strongest inhibitory feedback loops for decreasing the intensity and negativity trends of the conflict.

Another alternative is to highlight the many in-degree links that feed conflict intensity with dotted lines to support the sense that there is considerable energy and tension associated with the reporting of bias, and also to help provide a more detailed understanding of the myriad sources of this energy, in addition to the acts themselves, feeding these tensions.

Various factors worked in concert with local concerns of inadequate grievance procedures and biased investigatory panels to intensify not only the significance but also the likelihood of perceptions of bias at MEALAC. It was a multiply determined phenomena that culminated in high levels of tension at MEALAC. This is not to suggest that acts of bias did not occur at MEALAC. It merely accounts for the level of sustained tension surrounding the events.

This analysis simply provides more options. It suggests that it may be more than ineffective grievance procedures driving the conflict, and that much more could be done to address these tensions—for instance, by addressing the climate at MEALAC, working across universities to stem acts of bias, and broadening the mandate of the investigatory panel beyond the grievance system.

The point to stress here is that the burgeoning area of network studies has begun to provide us with a new grammar for characterizing, exploring, analyzing, and ultimately learning from the science and art of conflict feedback loop–mapping. These maps and analyses can help us to become more aware of the context of problems—and to work within their complexity to identify key levers for change. Such an approach can help stakeholders regain a sense of efficacy in situations that tend to elicit hopelessness.

Once dynamics are identified, it becomes possible to home in on what’s most important: increasing probabilities for resolving the conflict.

2. Identify local actionables. Once you have mapped and explored the broader view of the feedback structure of the conflict, it can be immensely helpful to focus in on more local elements and links that are

actionable. 18 This means those things that can feasibly be addressed. If you are the president of Columbia University, there isn’t much you are going to be able to do about the intifada, the Israeli pullout from Gaza, or the actions of the Israeli ambassador. So it simplifies your task if you eventually drop the nonactionable elements (dashed-line ovals) and focus in on those you might be able to do something about, such as directly refuting untruths and inflammatory claims in editorials, blogs, and the documentary; enhancing tolerance through support of new and ongoing campus projects; joining with other university presidents to address these issues nationally; and cracking down on class hecklers and issuers of death threats. These are all feasible actions, informed by the complexity of events, that can affect the probabilities of constructive change on campus. But they should only be targeted after a fuller mapping of the system has provided a sense of the context in which these elements are operating.

3. Locate (carefully) what is already working in the system. Laura Chasin is former director of the Public Conversations Project and facilitator of the Boston dialogue over abortion. When she enters a new community she is working with, which is deeply divided over a difficult conflict, she first tries to identify the existing “networks of effective action.” These are the individuals and groups that somehow manage to stay connected to parties on the other side of the conflict; they work effectively and constructively to keep relationships and dialogue going, even under stressful and dangerous circumstances. These social networks can often be found in conflicts within families, communities, and between nations. In more threatening environments, they may be forced to go underground. But typically they are there, despite the danger, working carefully to keep communications open.

From the perspective of complexity science, these individuals and their networks are evidence of latent attractors for constructive relations operating within these families and communities. Given that they are usually locally motivated, well networked, and typically well informed, they often present a vital resource for bolstering alternative approaches to destructive conflict in the system; they provide hope and possibilities in an otherwise impossible situation. However, they must always be identified, approached, and supported carefully, as their covert status is often a necessary defense against alienation or direct attack, typically from members within their own groups or communities.

But these constructive networks are merely an illustration of a larger point—that there are usually processes and mechanisms already operating in every conflict system, no matter how entrenched, that are functional and constructive. Think of them as antibodies in the body of the conflict, quietly fighting against the spread of the 5 percent infection. These constructive forces can often be overlooked in conflict analyses, as the suffering and crises associated with the 5 percent grab our attention and make the problems salient, usually at the expense of existing buffers or remedies. But a thorough scan of the system can help to locate its more functional components; these include local norms and practices that prohibit aggression and violence beyond certain levels, indigenous grievance systems or other regulatory mechanisms considered impartial and fair, or widely respected members of families or communities that might be able to play a more actively constructive role in addressing disputes.

Returning to the MEALAC case, we can now see that the Columbia community had many constructive resources already operating around the time of the initial intensification of the conflict. The Office of the Ombuds, the Office of Student Affairs, two well-known conflict resolution centers on campus,

19 student-based conflict resolution groups, interfaith religious figures and organizations, and interethnic tolerance-focused student organizations are just some of the well-known entities functioning at Columbia during this time. And it is likely that a more thorough scan of the social-political networks in the community would identify many other less obvious resources. Identifying, engaging, and supporting such groups and resources, even in a low-key manner, takes advantage of the existing infrastructure for enhancing constructive dynamics and respects the local knowledge and expertise of these actors.

4. Identify integrative catalysts. Another tactic for managing the overwhelming nature of complicated, evolving conflict systems is to attempt to identify

integrative catalysts. Typically these are individuals who, for reasons of their own personal or professional development, somehow embody the different conflicting identities and tensions inherent to the conflict. They may simply be trusted friends or family members, or have multicultural or multiethnic identities, but typically they hold a special status that allows them to stay above the fray and not get forced onto one side or the other. Here is a quote from one such individual:

I decided to go to the march to protest the complicity of the Israeli government in that massacre and the complicity of the Israeli army and calling for a commission of inquiry . . . As I got down to the march . . . there were a lot of Arabs that were marching with signs that said “Jewish star = swastika” and had pictures of the massacred babies that said “Israel has blood on its hands.” Now I felt all of the sudden, “whoa—I cannot join that march.” I really feel something wrong has happened here, that it should be investigated, I feel that students have a right to speak out, but that message didn’t resonate with me. It went right to the place of blame without even looking for facts or collecting information. I can’t go there. On the other side of the street were all the Jewish student groups protesting the Arab student groups and responding to their messages saying “Israel right or wrong” and “Israel shouldn’t come under anyone’s scrutiny” and “Israel is above the law” and I thought “crap, I can’t go over there either. I have nowhere to walk.” And so at that moment some friends and I formed a third group.

—a Jewish Israeli, 2002

These integrative agents can present important opportunities for boundary spanning and peacemaking. They personify an integrative solution. In the history of the Middle East peace process, individuals like Yitzhak Rabin (a military hero and general in the Israeli army who turned peacemaker as prime minister), Anwar el Sadat (Egyptian president, Arab, former revolutionary, and peacemaker with Israel), and Amos Oz (Jewish Israeli writer and journalist, founder of the “land for peace” NGO Peace Now) have played such integrative, boundary-crossing roles. In intractable identity-based conflicts these roles are vital. They are at times fraught with danger—Rabin and Sadat were both assassinated by members of their own groups—and so need to be engaged and supported with proper caution and care.

5. Take time seriously: visualize the attractor landscape of the conflict. The many different conflict elements and networks of reinforcing and inhibiting feedback loops that make up the 5 percent ultimately work together to constitute the conflict’s attractor landscape. In other words, the conflict maps provide a sketch of the process architecture of the conflict: how the skeleton, tissue, circulatory, and nervous systems of the living, evolving body of the conflict operate together. Conflict-mapping is like taking an X-ray of the internal workings of the body, an excellent tool for diagnosis and treatment planning.

Ultimately, however, we have found it useful to move from mapping to working with a simple visualization software program to begin to see how the different elements of a conflict interact together over time. This is critical for focusing our understanding on how the conflict system evolves and establishes temporal patterns or attractors across time.

THE ATTRACTOR SIMULATION: OVERVIEW

As described, a conflict system can be characterized on three dimensions: its current state, its potential for positive interactions, and its potential for negative interactions. But characterizing conflict on these three dimensions is not straightforward for most people. Moreover, any factor influencing a conflict system may affect each of the three aspects in different ways. For example, an increased police presence during a student protest at Columbia may decrease the momentary state of violence on campus. But it may also decrease the strength of the attractor for future positive interactions between the administration and the community, and at the same time increase the strength of the attractor for future negative interactions. Therefore, understanding the multiple consequences of an action can be a daunting task for anyone involved in a dynamic conflict.

The Attractor Software platform has been developed to assist disputants, conflict practitioners, policy makers, and other stakeholders in addressing conflicts without neglecting the dynamic properties and complexity of the systems in which they work. It allows them to see how all the pieces of their 5 percent puzzles fit together and evolve, and ideally how they can be changed.

The Attractor Software is a visualization tool designed to help users see the three dimensions of systems described above. It prompts the user to specify the key factors influencing the conflict (ideally generated from their mapping exercises), the actions that can be undertaken, and to estimate the consequences of these actions with respect to three types of outcomes (current state, potential positive, potential negative). By evaluating each factor, the user estimates the strength and the direction of the influence of each factor on the whole conflict system. The software merely visualizes the understanding of the user; it is a tool for describing what parties and interveners have identified, based on their own expertise, experience, and mapping of a case.

Research on the use of Attractor Software in conflict resolution trainings has shown promising effects.

20 Two studies conducted at the University of Warsaw in Poland compared the effects of training in Attractor Software to standard integrative negotiation training. All participants were trained in integrative negotiation; however, only one group learned to negotiate with the help of Attractor Software and the integrative negotiation model. Participants who worked with Attractor Software found it much easier to communicate with their negotiation partners and reported a better understanding of the negotiation process. But the most interesting finding was that although the groups did not differ in terms of their sense of satisfaction with the resolution of the conflict, there were significant differences in the long-term stability of the agreements the groups generated. In fact, each pair that negotiated with the help of Attractor Software achieved durable long-term solutions, whereas the majority of the other pairs failed to achieve such results. These findings speak to the fact that even a highly satisfying outcome may be not be durable; this fact may go unnoticed by the parties until the consequences of their actions come back to haunt them. Attractor Software can serve as a nontrivial yet simple tool that potentially increases the durability of agreements.

To date, the Attractor Software has been used in a variety of settings, including in New York City public schools, at the West Point military academy, at a state-level genocide prevention institute at Columbia University (Engaging Governments in Genocide Prevention), and in negotiation and mediation trainings in communities and at universities and conferences around the world. It is also being used by Dutch UN peacekeepers and FARC leaders in the Colombia conflict.

But don’t let that intimidate you! The software was developed to be easy to use. Thousands of individual users have logged on to our website (

http://www.iccc.edu.pl/as/introduction.html) to access and work with the program. I invite the reader to go to the appendix to read more about working with the Attractor Software.

In the next two sections we discuss the actions available for shaping the long-term potential patterns in conflicts. We move from the discussion of understanding the past and the present in a conflict to acting on the future. We do so by describing the practices and actions involved in working incrementally to transform the attractors themselves.

PRACTICE II: BUILD UP AND TEAR DOWN

Finding and implementing sustainable solutions to intractable conflicts essentially comes down to altering the system’s attractor landscape. This may sound abstract, but it simply means thinking and working long term.

The film American History X provides an excellent illustration of some of the key principles of the Attractor Landscape Model, and in particular the role the future plays in changing intractable mindsets. It presents a disturbing yet compelling portrayal of a young man, Derek Vinyard, a brutal and charismatic neo-Nazi skinhead. Derek is a rising leader in the skinhead movement in the Venice Beach area of Los Angeles.

The film shows us how a constellation of factors—trauma from the early loss of his father, adolescent angst, inadequate parenting, racism, hard economic times, unemployment, peer modeling, idle time, manipulative adults, and a strong neo-Nazi ideology and propagandistic rhetoric—can combine to send a youth down the path of extreme hate and violence.

It also effectively portrays how the youth’s attitudes, in-group and out-group perceptions, identities, politics, and behaviors collapse together; they form into simple, all-encompassing “us versus them” world-views that focus on the annihilation of out-groups (minorities, gays, and immigrants are seen as insects that deserve to be exterminated). Most important, it artfully captures Derek’s transformation. He suffers severe ruptures in his ultracoherent worldview; in prison, Derek is attacked by a group of skinheads, and later he is rescued from another gang by a young black man. Coupled with a latent alternative identity and a raison d’être—his deep love for his younger siblings and mother, who need his protection and leadership—these experiences lay the groundwork for his transition from a violent attractor to a man leading a dramatically more constructive life.

This laying of groundwork for constructive relations and peace is the primary aim of practice II. The main objectives here are to support and enhance latent positive attractors and make them more attractive, and to inhibit and deconstruct negative attractors to make them less attractive. To build up and tear down.

BUILD UP: GROWING HIDDEN POSSIBILITIES

Here the idea of latent attractors discussed earlier comes into play. We have found that the malignant thoughts, feelings, and actions that characterize a person’s or group’s dynamics in a 5 percent conflict represent only the most obvious attractor for the conflict. In particular, where there is a long history of interaction between people or groups, likely other potential patterns of mental, emotional, and behavioral engagement exist, including those promoting positive relations.

Take Ukraine and Poland. Relations between these countries had been hostile and tense for decades, going back to atrocities committed by both sides during World War II. However, their dealings go back many decades before the war, during which time they shared mutually beneficial trade and cultural relations. In fact, the strained relations that developed during and after World War II can be considered the exception rather than rule. Presumably, then, there existed an attractor for positive relations between Ukraine and Poland that was supplanted by a negative attractor during the war. It is therefore not completely surprising that the mutual antagonism, which had lasted for decades, gave way in a dramatic fashion to mutual solidarity during Ukraine’s Orange Revolution in 2004–2005. In social relations, these types of “flips” from one attractor to another are more common than one might think. But they require the presence of a sufficiently robust latent alternative for the relational dynamics.

But latent dynamics are hard to see. Some changes in a system can be easily observed because they affect the current (overt) state of the system. Other changes, however, may only affect the possible states of the system and thus not be immediately apparent. Such changes may remain latent for extended periods of time, yet manifest rapidly in response to external influences and events that seem relatively minor. Although movement between attractors may be rapid and abrupt (back and forth between constructive and destructive patterns), the change of attractors themselves is likely to be far slower and more gradual. Thus, when a specific policy or intervention does not produce a visible effect, this does not mean that it is futile. Rather, such activities may be creating, deepening, or destroying latent attractors in a system. In other words, they may affect the range of possible states rather than the current state.

With this in mind, identifying and reinforcing latent positive attractors—“traps” for peaceful or constructive relations—should be among the principle aims of both conflict prevention and intervention. With the 5 percent, the identification, support, and initiation of constructive forces within the system (common projects, citizen exchanges, dialogues, etc.) are critical for increasing the long-term chances that peaceful relations will resurface—whether they show short-term results or not.

Below we outline a few of the many actions available for creating and bolstering positive latent attractors. They include (1) stop making sense, (2) alleviate constraints on constructive networks, (3) circumvent the conflict, (4) employ weak power, (5) construct chains, (6) build on serendipity, (7) identify superordinate goals and identities, (8) rebuild social capital, (9) protect experiments and prototypes, (10) leverage the irony in impossible conflicts.

1. Stop making sense. As discussed earlier, rational decision making and game theoretical strategies for maximizing outcomes typically have little to do with the long-term tendencies of enduring conflicts. Certainly, vested interests and calculated decisions play a role, but it’s nothing like the bedrock role that affect (feelings of fear and hate, of loyalty and loss) plays in establishing the context for conflict dynamics. Emotions are the glue: the cement that holds attractors together. Some emotions also constitute a primary source of reinforcing feedback for the 5 percent. Feelings of anger and disgust, for instance, have been found to enhance a sense of certainty (coherence) in situations, thus bolstering attractors and future feelings of enmity.

21 Therefore, rational appeals for peace and tolerance will often fall well short of their objectives with the 5 percent.

With this in mind, we suggest that the main task involved in creating or enhancing latent positive attractors in the 5 percent is to help develop, foster, and trigger positive feelings between the parties. This may seem simplistic, but it’s everything. In fact, the more distant these attempts are from rational persuasion, from obvious attempts at swaying emotions, the better.

gThe good news is that if the parties had any type of constructive relationship prior to the conflict, or if they have had opportunities to experience each other’s’ humanity under better circumstances, likely there is some reservoir of positivity for their relationship, albeit latent. The bad news is the

negativity effect: the finding that negative emotions have something like a five-to-one stronger impact than positive emotions on relationships.

22 This usually makes it much, much harder to foster positivity in a 5 percent relationship.

In his Love Lab, one of the methods psychologist John Gottman employs with couples in conflict is to assign positivity exercises.

23 He will give one partner in an estranged couple the task of noticing ten positive things the other partner does during a week. This tends to elicit positive behaviors from one partner, and make them salient and noticeable to the other. By reminding both partners of this potential in their relationship, this activity triggers and reinforces the positive attractor latent in their dynamic. Of course, this method assumes that parties are willing and able to engage in the task, which is often not the case in the 5 percent. Nevertheless, simple initiatives like cultural and citizen exchanges, sharing of medical technologies, and disaster relief programs can go a long way in increasing positivity in an otherwise hostile relationship.

2. Alleviate constraints on constructive networks. As mentioned, virtually every conflict system, even the most dire, will contain people and groups who, despite the dangers, are willing to reach out across the divide and work to foster dialogue and peace. There are countless examples of this in the international arena: among Germans and Jews during the Nazi campaign in Europe during WWII; blacks and whites in South Africa in the 1980s; and today in places like Darfur, Somalia, Iran, and North Korea. These networks are often the centerpiece of latent constructive attractors for people and groups. However, the actions of these constructive agents are usually tightly constrained by the dynamics of the conflict. During times of intense escalation, these people and groups may become temporarily inactive; they may even go underground. But they are often willing to reemerge when conditions allow, becoming fundamental players in the transformation of the system. Thus, early interventions should engage with these individuals and networks, carefully, and work with them to help alleviate the constraints on their activities in a safe and feasible manner.

3. Circumvent the conflict. Recognizing that players in a conflict who have strong, negative 5 percent attractors often view peacemakers themselves as also being players in the theater of conflict, some interveners attempt to work constructively in these settings by circumventing the conflict.

The idea here is that a main reinforcing feedback loop of 5 percent conflicts is the conflict trap. This is a situation where the destructiveness of the conflict exacerbates the very negativity and strife that created the conflict conditions in the first place, and thereby perpetuates it. However, attempts to address these circumstances directly, in the context of a peace process, typically elicit resistance; they are seen as affecting the balance of power in the conflict (usually by supporting lower-power groups most affected by the conditions). Interveners recognizing this will work to address these conditions of hardship, without making any connection whatsoever to the conflict or peace processes. To some degree, this is what many community and international development projects try to achieve. The difference is that this tactic targets the conditions seen as most directly feeding the conflict, and requires that every attempt be made to divorce these initiatives from being associated with the peace process.

This approach is employed in some of the work of the Ashoka Fellows, social entrepreneurs working in zones of armed conflict. Typically, they are local people working in innovative ways to help rebuild social capital and provide a sense of efficacy in struggling communities. They address basic needs destroyed or neglected during a conflict, such as building community latrines in slums, organizing dances for idle youth, providing local phone networks to allow isolated people to better communicate with neighbors, etc.

24 This

unconflict resolution strategy can help address some of the negativity and misery associated with conflicts, without becoming incorporated (attracted) into the polarized “good versus evil” narrative of the conflict. This is an important idea that has widespread implications for our understanding of peacemaking in settings with ultracoherent destructive attractors.

4. Employ weak power. Sometimes more direct intervention into a conflict is necessary. Employing

weak power has proven effective at fostering positivity and eliciting less resistance.

25 Strong conflict systems, with wide and deep attractors for destructiveness and narrow and shallow attractors for peace, will often reject out of hand most strong-arm attempts to force peaceful relations. History provides countless examples of strong outside parties’ failure to forge peace in such systems. Consider the relatively ineffectual role of the United States in brokering Middle East peace.

Nevertheless, sometimes peace does emerge out of long-term conflicts, and we suggest that one reason may be the power of powerlessness; that is, the unique influence people and groups with little formal or “hard” power (physical strength, military might, wealth) but effective “soft” power (trustworthiness, moral authority, wisdom, kindness) can have in these settings.

26 Weak-power third parties are at times able to carefully introduce a sense of hope for change in the status quo; a sense of doubt or dissonance in an ultracoherent “us versus them” meaning system. And they can also begin to model and encourage other more constructive means of conflict engagement (shuttle diplomacy, mediation, negotiations).

This is the extraordinary role that Leymah Gbowee and the Women’s International Peace Network (WIPN) played in the early 2000s, when they helped end Liberia’s decades-long civil wars.