![]()

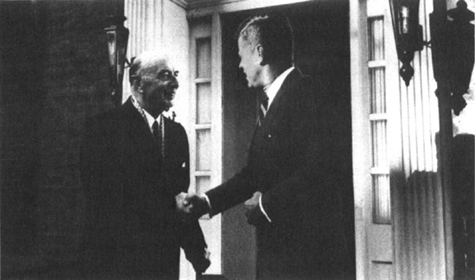

Lovett and President-Elect Kennedy

“No, sir, my bearings are burnt out”

Dean Acheson was waiting on a platform in New York’s Pennsylvania Station on a snowy March evening in 1958 when a porter ushered him to the stationmaster’s office. He found there an elegant, soft-voiced young woman whom he knew from Georgetown society, Jacqueline Kennedy. He knew her stepfamily, the Auchinclosses, from school days; the Auchincloss men were well represented at Groton and in Scroll and Key at Yale. He greeted her cordially. She gave him a rather frosty hello.

The stationmaster apologized. A late-winter blizzard had delayed the train to Washington, and he was afraid it might take all night to get there. Acheson said that he would board anyway; so did Mrs. Kennedy.

By chance, their seats were together in the parlor car, and as soon as they settled down, Mrs. Kennedy lit into Acheson. How could he attack her husband so in his book? Acheson sighed and recalled that in Power and Diplomacy he had harshly criticized a speech by Senator Kennedy that called on France to grant independence to Algeria immediately. “This impatient snapping of our fingers,” Acheson had written in Power and Diplomacy, was a poor way to treat an old and valued ally. Acheson turned to her and remarked that they could spend the rest of a long train ride fighting, or they could be pleasant. “All right, let’s be pleasant,” she said, but continued to sulk. They passed the night, Acheson later recalled, with “desultory conversation and troubled sleep.” Mrs. Kennedy did not let go after they finally arrived in Washington. She wrote Acheson demanding to know “how one capable of such an Olympian tone can become so personal when attacking someone for political differences.” Acheson responded dryly in a note to “Jacquie” that “the Olympians seem to me to have been a pretty personal lot.”

Dean Acheson did not have easy relations with the Kennedys. He had occasionally shared a ride with Senator Kennedy from Capitol Hill to Georgetown after Democratic Party meetings, but the conversation was never all that warm. “I would not say that we were in any way friends—we were acquaintances,” Acheson later recalled of their relationship. He distrusted the Kennedys, or more precisely Joe Kennedy. At lunch at the Metropolitan Club, he would dismiss Joe as a social-climbing bootlegger who had bought his spoiled son a seat in Congress. Acheson could not forgive the father for siding with Neville Chamberlain and appeasement in World War II.

John Kennedy, who believed in the existence of an American Establishment, very much wanted its approval. The Kennedys had overcome much of their social insecurity, they had conquered Harvard, including its Brahmin sanctuaries. But the family felt slightly cowed by the disciples of Stimson and Marshall, the Achesons, Lovetts, and Harrimans who had come from Wall Street and the great law firms. John Kennedy himself had more admiration for the cool toughness and unflinching pragmatism of Lovett and Acheson than he did for his more liberal advisers, men like Bowles and Galbraith, whom he considered idealistic but slightly mushy.

Acheson was the most intimidating exemplar of the Stimsonian tradition. Young Kennedy, perhaps sensing Acheson’s dislike of his father, was stiff and ill at east around the old statesman. Acheson later recalled that Kennedy was so deferential to him that he made him feel old. It is too bad; the two had a common irreverence and might have enjoyed each other’s company.

Acheson had hoped to block John Kennedy’s nomination for President in 1960 by backing Senator Stuart Symington, a fellow Yale man. “Maybe we should all give Jack a run for his money—or Joe’s,” Acheson wrote Harry Truman in April of 1960. Like Acheson, Clark Clifford backed Stuart Symington, a fellow veteran of the Truman days when Clifford had been a presidential adviser and Symington Secretary of the Air Force. But Clifford was a flexible man, a skillful, discreet operator who knew how to smooth over strained relations and who by nature gravitated to power. He had handled touchy legal problems for the Kennedys, suing columnist Drew Pearson for alleging that Kennedy had not been the true author of Profiles in Courage, and, more recently, quietly disposing of an even more delicate matter, a charge by a woman that she had once been engaged to marry JFK. In the late spring of 1960, the Kennedys called on Clifford again. Harry Truman had been openly denouncing Kennedy, in part for his Catholicism. Could Clifford restrain the former President? Clifford went to Acheson, pleading the need for party unity. Acheson, a good Democrat, agreed to intercede with Truman. On June 27, before the Democratic Convention, he wrote “the Boss”: “Could we make a treaty on what we shall not say?” He laid out a list of “It’s not dones”: “I. About other Democratic candidates: (a) Never say any of them is not qualified to be President. . . .” Later he asked Truman, “Do you really care about Jack’s being a Catholic? I never have. It hasn’t bothered me about de Gaulle or Adenauer or Schuman or DeGasperi, so why Kennedy? Furthermore, I don’t think he’s a very good Catholic. . . .” Still, Acheson remained dubious about JFK. In mid-September, he wrote Archie MacLeish, “The best campaign cheer I know is the current gag, ‘anyway, they can’t elect both of them.’” In October, Acheson bowed to the modern age and rented a television set to watch the presidential debates. He was so put off, however, by television as well as the candidates, that he returned the TV set before the second debate.

Almost immediately after his election, John Kennedy called on Acheson at P Street. Acheson offered him a martini, but Kennedy took tea, setting a precedent that did not particularly please Acheson. The cameramen tromping through his parlor to record the young President-elect seeking the counsel of the elder statesman further irritated Acheson.

Kennedy said that he needed Acheson’s advice on three positions in his Cabinet: State, Defense, Treasury. He quickly assured Acheson that he had no intention of appointing a “soft” liberal for State; he ruled out Stevenson and Bowles. But he had no one else clearly in mind. He knew Bill Fulbright, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, from the Hill. Acheson dismissed Fulbright. The Arkansas senator was a “dilettante” who liked to “call for brave bold new ideas but doesn’t have any brave bold new ideas.” Acheson then made his own nomination: Paul Nitze. He realized that Nitze was still too unknown, so he suggested a two-step process: initially, Kennedy should name as Secretary David Bruce, a well-bred, Princeton-educated diplomat who had served Acheson well as ambassador to Paris, with Nitze serving as the State Department’s number two. Then, after Nitze had gained visibility and experience, he would take over from Bruce—in a year or so. Looking diffident, Kennedy made no comment.

How about Jack McCloy? asked Acheson. Though Acheson was a loyal Democrat—indeed, an important party figure—it apparently did not bother him that McCloy was a Republican. McCloy’s party affiliation, however, did put off Kennedy. The President-elect interrupted to say that he wanted a Democrat.

Acheson tried a third name: Dean Rusk. Kennedy replied that he did not know Rusk. Acheson told him the story of how Rusk had volunteered for a demotion to take over the hot seat in Far Eastern Affairs, that he deserved “the Medal of Honor” for it. He recalled that Rusk had been steadfast on Korea, and remarked that he was “strong and loyal and good in every way.” He had heard from Bob Lovett and Jack McCloy that Rusk had made a fine president of the Rockefeller Foundation, his job since leaving State in 1952. Acheson recommended him “without reservation.” True, the old statesman added, there was always the risk that a number two or three would not work out as a number one, but one had to try in order to find out. Kennedy seemed to listen with interest.

The President-elect moved on to Treasury. He said that he had dispatched Clifford to New York to ask Bob Lovett. This brought a guffaw from Acheson. He told Kennedy that he was wasting his time. Lovett would never do it; he was not that well suited; he spent his time on Union Pacific matters and “a lot of fooling around with trains.” “Anyway,” Acheson continued, “if you want him why don’t you ask him yourself? If you give warning by sending Clark up, the old rascal will have affidavits from every doctor in New York saying that he’s going to drop dead.” Acheson added, “If you really want to put Lovett to work, make him reorganize the Defense Department. By the time he offended everyone in Washington, you’d have to let him go home.”

As the jaded older man sat back in his overstuffed chair, and the overeager younger man sat stiffly in his, the winter twilight dimmed in the parlor, the tea cooled, the conversation turned desultory. Kennedy perked up briefly when Acheson suggested C. Douglas Dillon for Treasury; JFK and Dillon were members of the same Harvard final club, the Spee; they had met there, Kennedy self-consciously revealed, several years before at reunion time.

Finally as night fell over Georgetown, Kennedy rose to leave. He had one final request for the old statesman: Would Acheson serve as his ambassador to NATO? The former Secretary of State demurred, saying there was no need to worry about him, that there was nothing he wanted, that he was glad to be of help, but as Churchill had said, “I’ve had enough responsibility.” In truth, the only job that interested Acheson was his old one.

Acheson was right about Lovett. When Clifford told him that his experience at State and Defense had made him a “rather unique package,” Lovett replied that he could not keep up with a bunch of forty-year-old touch-football players. At any rate, he would have to consult his doctors. That afternoon he hastened up to Presbyterian Hospital and came back with a letter stating that, in light of his medical history of bleeding ulcers and a good possibility of corrective surgery, the rigors of government service would be out of the question.

Still, Kennedy pressed. The more he learned about Lovett—his pragmatism, his common sense, his ability to get on with senators, his discretion—the more determined he was to bring him into his Cabinet. In fact, his brother Robert later recalled, Lovett was JFK’s first choice for all three top spots—State, Defense, and Treasury. Kennedy called Lovett out of a board meeting in New York on the morning of December 1 and asked him to come to Washington. “Is it urgent?” asked Lovett. “I’d like you to come for lunch,” the President-elect replied. Lovett took the first plane.

He encountered Caroline, aged three, in Kennedy’s front hall. She was wearing overalls emblazoned with an “H” and carrying a football. “That’s a hell of a way to treat a Yale man,” Lovett said to Kennedy as his host appeared. Lovett recalled that he was immediately charmed by Kennedy’s amused tolerance and affection toward his daughter. The young man and the old man sat by the fireplace; their conversation was both light and blunt. When Lovett mentioned that he had not voted for Kennedy, the President-elect just smiled. What did Lovett think of Ken Galbraith as an economist? “He’s a fine novelist,” answered Lovett.

Kennedy made the offer: State, Defense, or Treasury. “No, sir, I can’t,” Lovett replied. “My bearings are burnt out.” Lovett went on that every time he took a new job in Washington, the doctors took another slice out of his innards. Kennedy was understanding; he said he knew about working in physical pain. He asked Lovett for his recommendations.

Lovett said that Secretary of State was easy: Dean Acheson. Kennedy shook his head. Too many enemies in his own party, much less among the Republicans. Lovett paused and tried another name: Dean Rusk.

Kennedy and Lovett agreed that Dulles had been given too much license by Eisenhower. Kennedy said that he would be different. He wanted to make foreign policy himself. Lovett asked, “Do you want a Secretary of State, or do you really want an Under Secretary?” Kennedy laughed and said, “Well, I guess I want an Under Secretary.” Then Rusk would be perfect, said Lovett. He was the ideal staff man.

Kennedy asked if Lovett would serve him as an “unofficial adviser,” and the aging statesman nodded his agreement.* After a pleasant lunch, Kennedy walked his guest to the door. Newsmen were clustered outside. Lovett enjoyed having a drink with an Arthur Krock or a Joe Alsop, but he was shy of confronting the pack. Kennedy, coatless, escorted the old gentleman out into the snowy street, fended off the reporters, and put him in the President-elect’s personal limousine. “Take off,” he instructed the driver. Lovett was touched by the young man’s graciousness; the gesture was just the sort of thing Bob Lovett himself would have done.

Dean Rusk’s name kept coming back to the Kennedys. He was an unknown to the public, but he had the endorsement of both Lovett and Acheson. McCloy too backed him: “He has a fine mind and is experienced,” the Council on Foreign Relations chairman wrote the President-elect. Summoned to lunch with Kennedy, Rusk had seemed somewhat bland and unforthcoming to the President-elect, but perhaps his diffidence was simply humility.

On December 4, Rusk, Lovett, and McCloy were all at a board meeting of the Rockefeller Foundation at Williamsburg, in Virginia, when Kennedy called Lovett. The President-elect told Lovett that the list for State had narrowed to three: Bruce, Fulbright, and Rusk. Lovett strongly backed Rusk. He told Kennedy that Rusk had written an article in Foreign Affairs stating that the President himself should make foreign policy. Had Kennedy read it? He had.

The phone call to Lovett cinched it, according to Bobby Kennedy. The President-elect asked Lovett to approach Rusk about becoming Secretary of State.

The dour Georgian was suitably humble and grateful. But there was a hitch; he had no money, and he had children and a big mortgage. Lovett told him to rest easy; both he and Jack McCloy were on the board of the Rockefeller Foundation. They would make sure he received a comfortable termination bonus.

Acheson, Lovett, and McCloy would come to be disappointed with their choice. But in December 1960, both Lovett and Acheson had clear memories of a day, exactly ten years earlier, when Dean Rusk had stood up in the Secretary’s office, on December 4, 1950, and argued that the U.S. must not quit Korea, that it must follow the example of the British against the Nazis in 1940. In mid-December, Lovett described Rusk’s steadfastness to some reporters trying to learn about the new Secretary-designate: “If Rusk hadn’t been absolutely and immediately firm that we had to honor our word, that any cave-in on our part would be disastrous, who knows how the Korea business would have turned out? My impression is that Rusk picked up the loose ball and ran with it.” Lovett added, “I think you’ll find Dean Acheson saying the same thing.”

Unlike its earlier European counterparts, the American Establishment of the time was largely meritocratic, despite its web of schools and clubs; it positively relished finding and shaping promising poor boys like Dean Rusk. The willingness, even eagerness, to reach out to fresh talent from every quarter insured that certain values would be passed on along with power.

Rusk was considered a prize pupil. Unlike Kennan and Nitze, he had not been purged from the Dulles State Department, but rather promoted out of it. In 1952, Foster Dulles told Bob Lovett that he was “so impressed by Rusk” that he was “going to have to take him out of government and send him to the Rockefeller Foundation.” Lovett replied, “Damn it, Foster, you can’t do that. We need this man in Washington.” Dulles responded, “True, but I’d like him to fly a slightly wider radius.”

The polishing of the Cherokee County dirt-farm boy that began at Oxford continued in a boardroom at Rockefeller Center. Rusk was adept at expressing consensus; at the end of a contentious meeting, he could ably summarize the middle ground. “Rusk is the best explainer of things I know,” Lovett told Kennedy. Lovett particularly appreciated Rusk’s skills placating conservative congressmen (“If the Secretary of State gets on a white charger and starts making too much news,” Lovett would say, “he creates a lot of jealousy—notably where he can least afford it, in the Senate Foreign Relations Committee”).

These qualities, of course, appealed to Kennedy, who knew well what problems Dean Acheson had stirred on the Hill, and who wanted to be his own Secretary of State. If he could not have Bob Lovett, then Dean Rusk seemed like a handcrafted imitation.

Rusk was a reasonable facsimile. But there were some critical differences. Lovett was quiet and discreet and cautious, but he was ultimately a doer. Rusk was not. He lacked Lovett’s inner confidence, his sense of when to move, to carry through. Rusk was even in his own mind an imitation. He self-consciously modeled himself after Lovett’s patron, General Marshall. He did in fact share Marshall’s humility and stoicism, as well as his innate decency. Yet he utterly lacked Marshall’s decisiveness.

Lovett did have a few reservations about Rusk, though they seemed fairly minor at the time. He worried about Rusk’s “executive ability,” his capacity to make the jump from chief of staff to chief executive. He also thought Rusk was unduly obsessed with the Far East. These concerns, in the hard years ahead, would turn out to be not so minor after all.

At a three-hour lunch on November 28 with Clark Clifford (who had become the head of Kennedy’s transition team), Lovett was asked for his recommendation for Secretary of Defense. Lovett surprised Clifford by suggesting someone quite out of the Wall Street-Truman-era loop: Robert McNamara, the California-born, newly named president of Ford Motor Company. Lovett had discovered McNamara during World War II and brought him in from Harvard Business School, where he had been teaching, to help make the war machine more efficient. Using calculators borrowed from an insurance company, McNamara had set up a statistical control unit in the Pentagon to keep a daily record of all the Air Force’s warplanes, fuel, bombs, and ammo. Lovett had been enormously impressed with McNamara’s brilliance and intensity. When Henry Ford, whose mother owned a house nearby the Lovetts’ in Hobe Sound, called him after the war looking for able men for his auto company, Lovett sent him McNamara.

Lovett was struck by how unwieldy the Pentagon had become. He believed it needed a man who was both a numbers wizard and a forceful manager. He noted with approval that McNamara was an iconoclast, who chose to live in the university town of Ann Arbor rather than the corporate bedroom of Grosse Pointe, who was open-minded enough to join the ACLU and the NAACP. Lovett felt such independence of mind would be useful in tackling the bureaucracy. To Lovett, McNamara was just about right: a humanist technocrat with a strong will. He overlooked McNamara’s fixation with numbers and forgot, perhaps, the definition of a statistician he had given Harry Truman in 1952: “a man who draws a straight line from an unwarranted assumption to a foregone conclusion.”

When Sargent Shriver, Kennedy’s chief headhunter, called Lovett about the Pentagon job, he again recommended McNamara as “the best of the lot.” Lovett’s voice counted heavily with Kennedy; he told Shriver to gather the particulars on McNamara. The auto executive passed muster; he had even read and admired Profiles in Courage. After McNamara had been chosen for Defense, he went to see Lovett in New York, to seek his counsel. Lovett told him that his first order of business was to visit the chairmen of the Armed Services Committees, that without their support he was helpless. McNamara listened closely; as Lovett spoke, he took notes.

Sitting on his verandah in West Palm Beach, John Kennedy asked Paul Nitze if he would be interested in serving as National Security Adviser. Nitze said no. He wanted to be at Defense, where the buildup would come, where flexible response would actually be implemented. Nitze hoped that Kennedy would pick Lovett as Secretary of Defense with Nitze as his number two—with the understanding that Nitze would take over after a year or so.

McNamara’s appointment ended that idea. McNamara picked Roswell Gilpatric (Nitze’s old classmate at Hotchkiss) as his deputy. When Nitze heard the news, he hastily called Kennedy on his private number in West Palm to change his mind and accept the job as National Security Adviser. Kennedy did not return the phone call. Nitze had to settle for Assistant Secretary for International Security Affairs, ISA, the “little State Department” he helped create before getting purged from the Pentagon in 1953. As Nitze watched the White House make its own foreign policy in the years ahead—through the office of National Security Adviser—he would kick himself.

The National Security Adviser Kennedy did pick could hardly have been more acceptable to the old guard. McGeorge Bundy was the “next generation” par excellence. At Groton he had been the brightest boy; at Yale he was Skull and Bones. He had coauthored Colonel Stimson’s memoirs, On Active Service; he had edited Acheson’s collected speeches. He was Harvey Bundy’s son; he called Acheson, whose daughter was married to his brother, “Uncle Dean.”

He was a Brahmin (“Mahatma Bundy,” quipped the Yale Daily News), yet a true believer in meritocracy. He would scoff at the suggestion that he had been shaped by Endicott Peabody, whom he found a trifle quaint. The biggest influence on his life, he would later say, was Robert Oppenheimer. In this respect, he was just like Uncle Dean, who saw as his mentor not the Rector but a brilliant Jew, Louis Brandeis. Bundy shared as well some of Acheson’s intimidating acerbity and his incisive logic. He hewed to the same simple principles. (“Let me put my whole proposition in one sentence,” Bundy, a Yale senior, declared in 1940. “I believe in the dignity of the individual, in government by law, in respect for the truth, and in a good God; these beliefs are worth my life and more; they are not shared by Adolf Hitler.”) He approached problems with the same cool pragmatism.

Acheson was delighted to hear that “Mac” had been chosen as National Security Adviser. Acheson’s model for the job was the loyal, discreet Averell Harriman in the Truman White House. In fact, Bundy tried hard to keep a low profile and get along with Dean Rusk. But the focus of foreign policy making moved from the State Department to the White House during his tenure, and Bundy, forceful and incisive, unavoidably at times edged aside the more tentative Rusk. In the late sixties, Acheson was asked what he would have done if Mac Bundy had been National Security Adviser when he was Secretary of State. “Resign,” he answered.

Jack McCloy got his call in the midst of a dinner party in New York in early December. Arriving at Kennedy’s suite at the Carlyle, the newly retired chairman of the Chase Manhattan Bank sat and listened as the President-elect paced barefoot around the room. Kennedy told him that Lovett had suggested him for the Pentagon. “I’ve already done that,” grunted McCloy. How about Treasury then? “I’m not qualified,” said McCloy. Kennedy laughed, reminding him that he had been chairman of Chase Manhattan and president of the World Bank. McCloy said that he had done badly in economics in college. Kennedy had another offer. He wanted an arms control agreement with the Soviet Union. Would McCloy take on the task as his special adviser for arms control?

McCloy said yes. He had just become a senior partner at Milbank, Tweed, and it would be awkward to back out of his new arrangement. But he later recalled, “I had spent so much time organizing the destruction of things that I wanted very badly to do something constructive in terms of peace. Stimson was very concerned about the Bomb, and he impressed this upon me. It was sort of his legacy that I wanted to carry out.”

George Kennan was checking his mailbox at Branford College at Yale, where he had gone to teach for a semester, when an agitated undergraduate said to him, “Mr. Kennan, the President of the United States wants to talk to you.” Kennedy was calling to offer Kennan the ambassadorship to Poland or Yugoslavia. Kennan was delighted; he took Yugoslavia, whose independence from the Kremlin he had been among the first to predict.

Kennan had great hopes for the young President. Kennedy had won over the sensitive former diplomat a year earlier by writing to praise him for an article in Foreign Affairs that Kennan had written to rebut Acheson’s attack on the Reith Lectures. The article “disposed of the extreme rigidity of Mr. Acheson’s position with great effectiveness,” Senator Kennedy told Kennan, “and without the kind of ad hominem irrelevance in which Mr. Acheson unfortunately indulged last year.”

Kennedy was in most respects a conventional Cold Warrior, but he was sensitive to the need to improve relations with the Soviets. Unlike Dulles—and even Acheson—he wanted to hear out the Soviet watchers, to tap into some of the expertise that had been ignored for the last decade. He told Kennan that he did not want to be in the position of Truman, “entirely dependent,” on his Secretary of State for advice. Kennan was charmed by Kennedy’s solicitude. There was “a certain old-fashioned gallantry about him,” Kennan later recalled, a “Lindberghian boyishness.”

The day after he was elected President, Kennedy called Chip Bohlen and said that he had been sent a congratulatory telegram by Nikita Khrushchev. How should he reply? Taken aback, Bohlen told him to be courteous and avoid substance.

The phone calls kept coming. Kennedy wanted Bohlen’s advice almost constantly, about Khrushchev, the Soviets, Laos, even routine questions of diplomatic protocol. The two became social friends; Kennedy enjoyed Bohlen’s wit and easy charm. Unlike Dulles, Kennedy immediately recognized that Bohlen was a gifted diplomat, the best the Foreign Service had to offer. To Bohlen’s great credit, he did not forget that he was a Foreign Service officer first and the President’s friend second. Bohlen disapproved of Kennedy’s ad hoc conduct of foreign affairs and his impatience with normal State Department channels; he believed Kennedy’s disregard for the bureaucracy hurt morale. When Kennedy asked him, “What’s the matter with that State Department of yours, Chip?” Bohlen answered, “You are, sir.”

Bohlen had been rescued from Manila after Dulles’s death by the new Secretary of State, Christian Herter (a fellow St. Paul’s boy). Herter installed Bohlen as his special assistant for Soviet affairs (he could not make him Assistant Secretary or Counselor because he could not be sure of Senate confirmation). Bohlen stayed on as the department’s Soviet expert under Rusk, with the promise that he would become ambassador to either England or France.

Less than a month after his inauguration—on February 11—JFK summoned his Soviet experts to the White House for a strategy session. There were four: Bohlen, Kennan, Llewellyn Thompson (who had replaced Bohlen as ambassador in Moscow), and Averell Harriman. After nearly a decade in the wilderness, they were again being heard.

All of them urged Kennedy to take steps to remedy the deep chill that had again settled over Soviet-U.S. relations after the Russians had downed a U-2 spy plane over Soviet soil on the eve of a summit meeting between Eisenhower and Khrushchev. The summit had collapsed. Bohlen, backed by the others, urged Kennedy to seek another. Tensions were building in Laos, where the Soviets were backing a “war of national liberation,” and in Berlin, coveted more than ever by the Kremlin. There was much to discuss. Kennedy worried openly that he would be attacked by the right wing in Congress if he appeared too conciliatory. But he was curious to meet his Soviet counterpart face-to-face, and he agreed to seek a summit with Khrushchev.

Kennedy’s openness and energy, his eagerness to solicit the views of the old Soviet hands, “delighted” Bohlen, his wife, Avis, wrote Charlie Thayer a few days after the meeting at the White House. The heady whirl of early Camelot swept Avis away: “The atmosphere bubbles and sparkles like champagne,” she wrote Charlie. “All these new young alive faces bristling with desire to get started.” It brought her

back again to the days—almost of the war—conferences, meetings all the time—dinner parties and receptions . . . most exciting. The only hitch is that most of them are so young and now suddenly overnight Chip has become one of the “older men,” rather than the younger group. George Kennan was here for two days—looks 20 years younger and is so full of smiles and cheer and dying to get started. Chip and George and Averell etc. have seen the President a total of about seven hours. . . . This is just about twice as much time as Eisenhower gave to Tommy and Chip combined in 8 years!

Averell Harriman was hugely relieved to be back in the inner council, advising a President. He had recovered from the shock of losing to Nelson Rockefeller in New York by going back to his peculiar source of regeneration, to Russia. Characteristically he had wasted little time. On January 9, 1959, only a week after turning over the governor’s mansion to the Republicans, he had written Dean Acheson that he planned to tour the Soviet Union. “I don’t see any reason why I can’t plunge into battle just to keep trim,” he wrote his old friend. He even wanted to go on to Red China, a totally closed society in the late fifties. Harriman retained Acheson as his lawyer to obtain permission from the State Department. Ever the cheap multimillionaire, he had admonished Acheson: “Please keep your price reasonable because I have a lot of expenses these days.” The anti-Communist zealots hired by Dulles objected; Walter Robertson, the head of Far Eastern Affairs, told Acheson that Formosa and the other “free” Asian countries might think that Harriman was being sent by the U.S. to negotiate a secret peace with the Chinese Communists. Acheson was sarcastic. “You don’t mean to say that you believe people abroad would think you fellows are sending a Democrat to negotiate for you?” But he failed to get Harriman’s visa.

Harriman went to Russia ostensibly as a writer for Life magazine (he took as his ghostwriter and translator Bohlen’s brother-in-law, Charlie Thayer, who after his purge from the Foreign Service had become a free-lance writer). Slightly stooped, weary-looking, and as usual indefatigable, Harriman traveled eighteen thousand miles within the U.S.S.R. He was regarded as a visiting dignitary and remembered as a war ally; common people cheered him everywhere, in factories, in train stations, in the streets. Indeed, he drew bigger and more enthusiastic crowds in Russia than he had campaigning in New York.

At the end of his journey, Harriman was granted long audiences with Khrushchev, who bluffed and blustered and threatened. Walking in the garden of his dacha, the Soviet leader warned Harriman, “We are determined to liquidate your rights in West Berlin. Your generals talk of tanks and guns defending your Berlin position. Your tanks will burn and the rockets will fly.” But when Harriman said that he did not believe that the Soviets wanted to provoke war, Khrushchev calmed down. “We don’t want war over Berlin,” he said.

Though not a terribly subtle man himself, Harriman was able to understand what others in the frightened West failed to see. When Khrushchev fulminated “We will bury you!” he meant that Communism would outlast capitalism, not bomb it. Harriman was fascinated to hear Khrushchev run down Stalin as a brutal aggressor. He was reminded that Soviet Communism was not static, that it could evolve. When Khrushchev spoke repeatedly of the need for an arms-control agreement, Harriman believed he was sincere. Most of all, he was again convinced that the West could deal with the Soviets, provided the negotiations were handled by men like himself.

The Soviet leaders clearly believed that they could deal with him. He was a true capitalist; men like Khrushchev felt they could understand him, that he represented the real America. At a dinner, Khrushchev turned to Harriman and declared, “Do you suppose we consider it a free election when the voters of New York State have a choice only between a Harriman and a Rockefeller?”

When Khrushchev toured the U.S. in September of 1959, Harriman invited him to his house at 16 East 81st Street in New York, to sit in his library beneath his favorite Picasso and talk to some titans of finance and industry. About thirty were present, CEOs of large corporations, foundation heads, investment bankers. Offered a drink by Harriman, Khrushchev demanded some Russian vodka. The former governor gave him a glass of New York State brandy. “You rule America,” Khrushchev pronounced to the congregation of capitalists. “You are the ruling circle. I don’t believe any other view.”

The first question came from John McCloy (“as a matter of official precedence,” dryly noted an interloper at the gathering, John Kenneth Galbraith). It was not really a question but a statement. McCloy tried to persuade the Soviet leader that Wall Street was totally without influence in Washington. “Judge for yourself,” he said “Almost all the bills proposed by Wall Street are automatically rejected by the Senate.” Khrushchev stared disbelievingly at him and muttered with heavy sarcasm, “It appears that I have before me America’s poor relations.”*

In the fall of 1960, Harriman had called Khrushchev beseeching him to be equally tough on both presidential candidates, lest he help the Republicans by seeming to favor the Democrats. Harriman was delighted when Khrushchev wired him after the election to say the slate had been wiped clean, that the bitterness of the Dulles era would be forgotten.

Harriman had only one reservation about the forthcoming summit between Kennedy and the Soviet leader. He was worried that the green young American President would be shocked by the Russian’s bluster and bravado, his threats that “the tanks will roll and the rockets will fly,” and overreact by shouting back. Harriman wanted a private audience with the President to tutor him, to impart some of his collected wisdom on the handling of Soviet dictators.

Kennedy, however, was not listening. In truth, he had a low opinion of Harriman.

It is somewhat curious, in retrospect, that Harriman’s name was missing altogether from the list of potential Secretaries of State. But though he would later revise his opinion, Kennedy at the time thought Harriman too old, too deaf, and too political. “Never has anyone gone so far with so little,” Lord Beaverbrook had told JFK in 1958. A meeting with Harriman in November 1960, after the election, went badly: Kennedy asked a long, complicated question about foreign policy and Harriman answered, “Yes.” A second meeting in December was worse. The President had made a point and Harriman, thinking he had heard his aide Jack Bingham speak, growled, “Don’t be silly, Jack.” On the way out Kennedy said to another Harriman aide, Mike Forrestal, “Do you think that you can get Averell to wear a hearing aid?”

Nor did Harriman get any help from his old comrades. Lovett had been notably silent about his childhood friend when counseling Kennedy. McCloy would later say that Harriman’s Truman-era colleagues had grown dissatisfied with Averell’s politicking and increasing dovishness.

Harriman for his part had been cool to JFK, at least initially. John Kenneth Galbraith recalls hours spent walking up and down the beach at Sands Point in the summer of 1959 trying to persuade Harriman to back Kennedy for President, and hearing Harriman object to the fact that JFK “saw” Joe McCarthy. Harriman was finally persuaded largely by his perception that Kennedy would win. He even seconded Kennedy at the Democratic Convention, but he was disappointed because he believed the family never knew how hard he campaigned for JFK that fall (through a dozen states). He later told friends that his chances of a good job in the Administration had been torpedoed by old Joe Kennedy.

Arthur Schlesinger had mentioned Harriman to Kennedy on December 1. “He’s too old hat,” scoffed the President-elect. After some gentle pushing, Schlesinger and Galbraith managed to get Harriman the title of “Roving Ambassador.” The President considered the appointment to be “decorative,” Schlesinger recalled.

But Dean Rusk told Harriman that he planned to stay in Washington, and that he wanted Harriman to act as his emissary to Foreign Ministers’ meetings and other such (dreary) international gatherings. Without complaint, Harriman, then nearly seventy, packed his bag and went off to do what he did best: meet with other sovereigns.