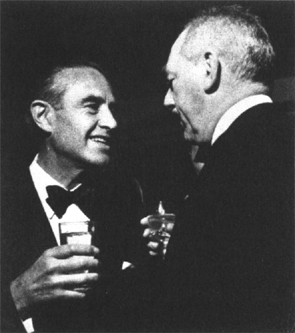

Harriman and Acheson

Last Supper of the Wise Men

In the fall of 1967, Lyndon Johnson badly needed reassurance. Brought home by television, the war was dragging on, stirring bitter dissent and strident, even cruel attacks on the President (“Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?”). Johnson’s Defense Secretary, Robert McNamara, the most self-confident man in his Cabinet, was visibly in torment. To his aides, Johnson worried that McNamara was on the verge of cracking up; he wondered aloud whether he was about to follow the example of James Forrestal.

Johnson felt martyred. He ranted against “gutless” bureaucrats who leaked “defeatist” information to “simpleton” reporters. “It’s gotten so,” he complained, “that you can’t screw your wife without it being spread around by traitors.” Like Lincoln, Johnson began to see himself a War Leader, waging an unpopular but noble struggle.

As he had at the time of escalation in 1965, the President turned to his Senior Advisory Group, the Wise Old Men (or WOMS, as they were called by White House staffers). There were eleven who responded to Johnson’s summons in early November: Dean Acheson, the chief elder; Clark Clifford, LBJ’s closest private adviser and a resolute backer of the war; Supreme Court Justice Abe Fortas, another LBJ crony and Clifford’s fellow hawk; McGeorge Bundy, the former National Security Adviser who had graduated to Wise Men status; Maxwell Taylor, the Kennedys’ favorite general and former ambassador to Saigon; Omar Bradley, the chairman of the JCS during the Korean War; Robert Murphy, General Lucius Clay’s political adviser in Berlin and a high State Department official under Dulles; Henry Cabot Lodge, former ambassador to Vietnam; Arthur Dean, Dulles’s law partner and U.S. armistice negotiator in Korea; Douglas Dillon, Kennedy’s Treasury Secretary and a leader of the New York Establishment; and George Ball, the in-house dove who had resigned as Under Secretary of State the year before. One elder statesman who had never left government was also included: Averell Harriman.

It was a formidable assemblage, a rich blend of Wall Street and Washington, soldiers and diplomats, men who had shaped and preserved a bipartisan foreign policy consensus for two decades. Some had always been members of the Establishment (four of the twelve had graduated from Groton), others had picked up their credentials along the way. But all shared a familiarity with power and a conviction that the U.S. must fulfill its rightful role as world leader.

There were, however, two noticeable absentees from this august gathering. John McCloy had dropped out of the Senior Advisory Group altogether by November of 1967, while Robert Lovett, though still listed as a member, failed to attend.

Asked about their views on the war almost twenty years later, both Lovett and McCloy take on almost identical expressions: quizzical, pained, slightly vacant, as if they were troubled by some vague and undefined illness. It is revealing, though perhaps not surprising, that both men have little recollection of their roles in the Vietnam War. They can remember what they did in 1947 in precise detail, but Vietnam remains a void in their consciousness. About all they can recall is that they were against the war. Indeed, both adamantly insist that they opposed U.S. involvement from the first. The written record, however, shows that when asked by the President if they backed a certain step, such as sending in more troops or stepping up the bombing, they invariably said yes.

By the autumn of 1967, McCloy and Lovett had decided to have nothing further to do with Vietnam. Though both men were busy, neither was diverted by pressing demands on his time. While McCloy dropped out of consultations on Vietnam, he continued to report to the President on his conversations with Middle Eastern potentates whom he had visited on behalf of his Big Oil clients. McCloy’s calendar for November 1 and 2, the dates of the Wise Men meeting, shows nothing but routine appointments. Lovett was suffering from his usual aliments and preoccupied with Union Pacific Railroad matters. But he had always found time to serve his Presidents before, and he could later recall no reason why he declined this particular call to duty.

Perhaps almost unconsciously, both men apparently decided that since they could no longer support the war, they would absent themselves from Johnson’s war councils. They had no advice to offer on how the war might be won, and to advise him to simply get out was unthinkable. So they chose to remain silent.*

In retrospect, the quiet defections of Lovett and McCloy should have warned Johnson and his aides that support was slipping even within the Eastern Establishment. But at the November meeting of the Wise Men, this telltale warning was overshadowed by an outpouring of support from those who did heed the President’s call.

Assembling for cocktails at seven-thirty in an eighth-floor diplomatic reception room at the State Department on November 1, 1967, the Wise Men were briefed by General Earle Wheeler, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The report from the field was buoyantly upbeat: all the statistics, the captured documents and body counts, showed that the U.S. was winning the war. The only problem, explained Secretary of State Dean Rusk, who was acting as host that evening, was that the public did not know it.

The Wise Men accepted the Administration line. Most spoke out in favor of the war effort. Acheson dryly remarked that the bulk of student dissent stemmed from an understandable desire to avoid combat. “There was hardly a word spoken that could not be given directly to the press,” Walt Rostow exulted in a memo he wrote to the President after the meeting that night. “You may wish to have a full leadership meeting of this kind, introduced by yourself, after which you could put the whole thing on television.”

Johnson met with the Wise Men the next morning in the Cabinet Room. “I have a peculiar confidence in you as patriots and that is why I picked you,” he began. He wanted to know if he was on the right course in Vietnam, and if not, how to change it. The lack of public support and the negative press, he added, troubled him.

Acheson was the first called upon by the President. General Wheeler’s briefing had encouraged the old statesman. “I got the impression that this is a matter we can and will win,” he said. He had one caveat: He did not believe the bombing would bring Hanoi to the negotiating table. “We must understand that we are not going to have negotiations,” he told the President. “When these fellows decide they can’t defeat the South, then they will give up. This is the way it was in Korea. This is the way the Communists operate.”

He was resolute: “We certainly should not get out of Vietnam.” Then, as Johnson listened intently, he began to reminisce about another dark moment for an earlier President, the Chinese surprise attack in Korea in 1950. Acheson recalled that the military had become defeatist, but that Dean Rusk and George Kennan had come to his office and urged him to implore General Marshall to buck up the military. “We want less goddamn analysis and more fighting spirit,” he quoted himself as saying. Together, they had persuaded Truman to hold fast, and a humiliating defeat had been averted.

Acheson’s recollection of Korea was particularly vivid. He was, at that very moment, writing about the Korean War in his memoirs, poring over his memoranda of conversations, reaching back into his memory, and reliving that most intense crisis of his life. “The more I watch this war the more parallels I see to Korea and the more I admire my Chief,” he wrote John Cowles (the “Chief” to Acheson was and would always be Truman, not his successor of the moment).

When he had finished recollecting Korea, Acheson made a suggestion to President Johnson out of another chapter of his memoirs. He told how his Citizens’ Committee for the Marshall Plan had organized groups of leading citizens in every city with a population over 150,000 to talk up European recovery and create popular understanding and support. Such a committee was needed now, said Acheson: influential men to carry forth the word.

Johnson next called on the second generation. Mac Bundy said he agreed with nearly everything Acheson had said. Like Acheson, he was strongly influenced by Bob McNamara’s disenchantment with the bombing, and he downplayed the significance of air strikes against the North. He further shared Acheson’s view that negotiations were a false hope, even though, he acknowledged, the Administration could not admit this publicly. The real focus, he said, should be on strengthening the South. “Getting out of Vietnam is as impossible as it is undesirable,” he declared. What was needed was more public support. The Administration should emphasize, he concluded in that memorable phrase, “the light at the end of the tunnel.”

As he listened through the morning and at lunch, Johnson heard only determination to press on with the war. General Bradley, for instance, said that what was needed was more patriotic slogans. He had been to Vietnam and he could report that troop morale was high; the men got ice cream three times a week, and of all the soldiers he talked to, he heard negative remarks from “only two colored soldiers from Detroit who were more interested in the riots in Detroit than Vietnam.” Clark Clifford declared that during Korea everyone had complained about “Truman’s War,” but just as that war had been right and necessary, so was this one. Johnson, cradling his four-month-old grandson, Patrick Lyndon Nugent, in his lap, basked in the warming talk of such esteemed men. There was, he concluded as the meeting broke up after lunch, “a sense of clarity and calmness in the group.”

The serenity was briefly interrupted as the elder statesmen filed out of the Cabinet Room. George Ball had said very little during the meeting, but he was unable to contain himself. Deeply discouraged by the war he had opposed for so long, disappointed in his colleagues from the Establishment for not seeing its folly, he burst out at Dean Acheson and the distinguished men around him: “I’ve been watching you across the table. You’re like a flock of buzzards sitting on a fence, sending the young men off to be killed. You ought to be ashamed of yourselves.” The old men just stared back at him, stunned.

This dissonant note was ignored and soon forgotten by Johnson’s advisers. They set about implementing the public relations campaign suggested by the Wise Men. The U.S. ambassador to Vietnam, Ellsworth Bunker, and the commander of U.S. forces, General William Westmoreland, made a speaking tour envisioning “the light at the end of the tunnel.” Westmoreland declared: “I am absolutely certain that whereas in 1965 the enemy was winning, today he is certainly losing.” The U.S. had reached the “crossover point”: it was killing more of the enemy than the North Vietnamese could replace. On the peace front, Lyndon Johnson took off to Rome for a private audience with the Pope, to whom he gave a plastic bust of himself. Meanwhile, thousands of Viet Cong were slipping silently into the cities of South Vietnam as the lunar New Year known as Tet approached.

Eyes heavy, jaws slack, Averell Harriman had sat quietly through the Wise Men meeting. He made no comment about the war at all, opening his mouth only to agree glumly with Acheson that the Senate Foreign Relations Committee was no good at all, that it did not begin to compare with its heyday under Arthur Vandenberg.

Harriman was trying to stay low and on Johnson’s right side. He continued to believe in a negotiated peace—unlike most of the other Wise Men—but he did not press his opinion publicly. His views were already well known to LBJ. “Harriman continues to believe that the best road to peace lies through the Communist capitals,” Mac Bundy wrote the President that November, “and that he is the right man to travel that road.”

Early in December, Harriman read with rising scorn some excerpts, printed in the Washington Post, of a TV interview of Acheson about the war in Vietnam. Acheson had been particularly prickly and querulous, dismissing a negotiated settlement as impossible and ridiculing his interrogators, a panel of college students, for fuzzy thinking. Repeatedly, Acheson likened the war in Vietnam to Korea, and insisted that the U.S. had no choice but to stick it out.

To Harriman, it was Acheson who was guilty of specious reasoning, not the students. He decided it was time to set straight his former rowing pupil.

Harriman was not so awed by Acheson as were most others, including the President. “To you he’s the great Secretary of State,” he would growl to his aide Dan Davidson. “But to me he’s the freshman I taught to row at Yale.” His relationship with Acheson was still tinged with rivalry and even resentment, yet he felt with Acheson a sense of shared history. “I rejoice that you are rapidly approaching the years of discretion,” he had written Acheson in a teasing 73rd birthday note in April of 1966. “How kind of you to cheer me on this depressing anniversary,” Acheson responded. He assured Harriman that he had no intention of becoming discreet.

In the early evening of December 12, 1967, Harriman took the short walk through Georgetown from his house on N Street to Acheson’s house on P Street, where his old friend greeted him at the door and showed him to his front parlor. It was a cozy room of books and memorabilia, with a picture of Stimson and a Yale rowing cup and a comfortable settee by the front windows where the two old men could sit and talk.

Harriman did not hesitate to get to the point. He had long felt that Acheson was too rigid, too stuck in the past, and he told him so. He proceeded to lecture: Vietnam was entirely different from Korea, he said. Russia and China were no longer allies. In fact, the two countries were bitter enemies. Moscow wanted to end the war. The fighting in Vietnam was guerrilla, not conventional warfare. A war of attrition, so effective in Korea, was futile against the Viet Cong. It was impossible to stamp out the Communists militarily. The real problem was that Johnson was afraid to settle the war for fear of a right-wing reaction, and he was constantly pressured by the military and those two hawks, Clifford and Fortas, to widen the fighting.

Acheson listened to this litany without interrupting. To Harriman’s surprise, he was almost agreeable. He said that he personally worried more about the left-wing nuts than the right-wing ones, but in any case, he was contemptuous of the opinions of Fortas and Clifford. What is more, he was highly suspicious of the military. This was one lesson from Korea that was applicable to Vietnam: don’t believe the rosy predictions of the generals.

The two men talked into the evening, keeping Acheson’s dinner guests waiting. Harriman implored Acheson to talk to the President, to level with him about his doubts about the war. Acheson protested that his influence had waned with Johnson, ever since he and Jack McCloy had “exploded” at the President over NATO. Forget that, said Harriman; go back to your old relationship: the President needs your advice to offset the military and the hawks. Acheson made no promises, but he seemed interested in trying to help.

Harriman was encouraged. “I found that he was not as rigid as I supposed,” he wrote in a memo to file describing the conversation. Was his old rival a potential seatmate in this last long pull? Harriman decided to grease the oarlocks. Less than a week later, he wrote Acheson asking him to sign a photograph of the two of them together. “I haven’t got an autographed picture of you, and I would particularly like you to autograph this one. It shows me trying to convince you of something I consider very important, and you’re having none of it! I enjoyed our chat the other afternoon. Please ask Alice to forgive me for keeping you away from your other guests so long.”

Back came the photograph from Acheson with an inscription: “To Averell Harriman, whose friendship has strengthened and delighted me for more than half a century. Dean Acheson.”

Acheson’s doubts about the war were deeper than Harriman realized. His own feeling about the Wise Men meeting was hardly the “clarity and calmness” Johnson had divined. “The meeting was exhausting, interesting, full of agony and effort on the part of all of us except Our Hero, who was not impressed,” Acheson wrote former British Prime Minister Anthony Eden (among friends, Acheson had taken to calling LBJ “Our Leader” or “Our Hero”).

The lesson of Korea cut both ways to Acheson. Standing up to the Communists was not the only moral; standing up to the military was another. In his memoirs, he was writing about MacArthur, and facing up to his own equivocation while the megalomaniacal general plunged on to disaster. With Bob McNamara, whom he greatly admired and felt for, he had been having long conversations about the hawks at the Pentagon and their passion for indiscriminate escalation. McNamara had broken publicly with the advocates of bombing during congressional testimony in August; afterward, Acheson wrote Eden:

Bob McNamara told me all about the situation a week ago. His report (to Congress) is the truth, but not the whole truth. Rather, a loyal lieutenant putting the best face on a poor situation. The fact is that the bombing of the North started as a morale builder for the South when things were very bad there. We have now run out of targets but the Republican hawks keep calling for more which produces useless casualties and encourages some Air Force fire-eaters to urge population bombing. LBJ has not HST’s courage to say no to political pressures. . . .

Vietnam was not all that worried Acheson. His well-ordered world was under serious assault in 1967—race riots in American ghettos, disarray in the Western Alliance—and Acheson held LBJ accountable. He confided to the former British Prime Minister:

For the first time, I begin to think that LBJ may be in trouble. It is not Vietnam alone. The country would probably stay with him on that. But Vietnam plus the riots is very bad. It spells frustration and a sense of feebleness at home and abroad. Everyone pushes the USA around. Yellow men in Asia, black men at home, de Gaulle a ridiculous type in Europe, and Nasser threatens to have the Arab states seize what is regarded as “our” oil properties. Americans aren’t used to this, and LBJ is not a lovable type. He is the one to blame.

Increasingly, Acheson began to worry aloud to friends that Vietnam was a dangerous diversion from Europe, that the blundering, unsophisticated LBJ risked bringing down the whole delicate structure of the Pax Americana. “Our Leader ought to be more concerned with areas that count,” he pronounced to guests at Sunday lunch at Harewood.

Acheson knew from talking to his son-in-law Bill Bundy that Johnson was becoming increasingly paranoid about leaks and dissent within his own Administration. The last real doubter, McNamara, was leaving the Pentagon in February to become president of the World Bank; a small, hawkish circle—principally Rusk and Rostow—now advised Johnson at the “Tuesday lunches.” These war councils in the President’s private dining room were closely held; line officers like Bundy were left to guess at Administration strategy. In self-defense, upper-level officials at State and the Pentagon who were growing ever more doubtful about the war began holding their own strategy sessions on Vietnam. Calling themselves the “nongroup,” they held “nonmeetings” over drinks every Thursday night. When Bundy contrasted this secretive and suspicious way of doing business with “the method of Acheson, Marshall, Lovett, and Harriman” during the Truman Administration, he was profoundly discouraged. The Tuesday lunch was “an abomination,” he believed, and the “nongroup” hardly an adequate answer.

Acheson anxiously watched his son-in-law suffer. His daughter Mary confided to him that her husband was miserable, no longer a hawk on the war but unable to see any way out. She feared that Vietnam would ruin his career and tear apart his family. Acheson listened quietly, stoical about what must be borne, but sympathetic and disturbed. On Sunday evenings, when he and Alice stopped in at the Bundys’ on their way home from Harewood, Acheson rarely discussed the war with Bill, preferring to let him rest, yet he could not help but see the physical and emotional toll. After Bundy returned from an LBJ around-the-world peace offensive at Christmastime, Acheson wrote Anthony Eden, “My poor son-in-law Bill Bundy came back on Christmas Eve from the flying circus—called by them the ‘journey to nowhere.’ In four and a half days he had spent five hours in bed. You and I lived in softer times, I am happy to say.”

Angry demonstrators carrying Viet Cong flags in front of the White House left Acheson taken aback at the virulence of the peace movement. “The anti-war demonstrations which we have just been through are the worst yet,” he wrote Eden on December 30. Yet the protesters were no longer just longhairs in the streets. At lunch at the Metropolitan Club, Paul Nitze, now Deputy Secretary of Defense, told Acheson about his own deepening opposition to the war. At cocktails before dinner at Lucius Battle’s, Stuart Symington, the onetime hawkish Secretary of the Air Force, berated Acheson about the war, insisting that it was time to either flatten Hanoi or get out. The two old Cold Warriors became so angrily engaged that they ignored their host’s repeated requests to come sit down for dinner. Many elegant dinner parties were similarly disrupted that winter in Washington; the war had divided not just the country, but the Establishment as well.

As Tet heralded in the Year of the Monkey in Vietnam, the Viet Cong exploded in Saigon and the major cities of the South. A suicide squad of VC penetrated the U.S. Embassy grounds. The U.S. retaliated massively with Operation Niagara, inflicting enormous casualties on the Communists. As a military venture, the Tet offensive was a defeat, but psychologically, it was a victory for the North Vietnamese. “If this is a failure,” stated Senator George Aiken of Vermont, “I hope the Viet Cong never have a major success.” The senator’s incredulity was shared by millions of Americans watching the carnage nightly on the news, seeing U.S. marines torch huts with Zippo lighters and hearing one commander calmly explain, “It became necessary to destroy the town in order to save it.” The press turned on the war: “What is the end that justifies this slaughter?” asked James Reston. “How will we save Vietnam if we destroy it in battle?” Once reliable backers of the war effort suddenly began to doubt—Walter Cronkite, The Wall Street Journal, Time, and Life.

Acheson could not escape the clamor even in Antigua, where he retreated in February for his annual winter holiday. As he wandered down the beach one afternoon, he encountered author Linda Bird Francke, who wore a peace symbol hanging from her neck. He examined it carefully. “What is that?” he asked. “The peace symbol,” she replied. He allowed that he had mistaken it for the logo of a Volkswagen. Even his old chums had become doves. John Cowles, the publisher of the Minneapolis Star and Tribune, and Jay Gould, scion of the robber baron, began to belabor the war over cocktails and croquet.

The policies of the past were not easily forsaken by Acheson, who had, after all, shaped many of them. “The constant cry of Mr. Lippmann and others for ‘new policies’ is the result of an illusion. Policies do not wear out or become obsolete like models of automobiles merely by the passage of time,” he wrote a friend in 1966.

Acheson was so scornful of the liberalism and change sweeping the 1960s that it is easy to think of him as a rigid old man, frozen in the myths of his own creation. Yet he was not dogmatic. He was a pragmatist, not an ideologue. Confronted with facts, he did not attempt to twist them to fit preconceived notions, or try to escape back into a dreamy world of bygone triumph. Even at age 74, he was able to face up to unpleasant reality. He was, what is more, a disciple of action. Crises made him alert, forceful, decisive; they drove him to act.

By the winter of 1968, Acheson was tired of being used. He was irked at being dusted off and displayed like a tarnished and nicked Cold War icon, manipulated by LBJ as well as by reporters like Reston and Joe Alsop, who would call him periodically for quotable wisdom. He felt that he was being not only used but taken; he suspected strongly that he was being asked to pronounce judgment on facts that were either false or incomplete. Acheson was a shrewd and meticulous lawyer; he would certainly never make an argument to the Supreme Court based on the quickie briefings he and other Wise Men had been served up on Vietnam. As one senior Defense Department official bluntly put it some years later, “Those briefings were a sham.” They were designed less to inform the elder statesmen than to convince them.

Acheson sensed this, and rebelled against it. In February of 1968, he decided he would either learn all the facts about Vietnam or cease to lend his support to the war.

He was summoned to the White House on February 27. Exhausted from spending most of the night in the basement of the West Wing, where a scale model of the besieged marine base at Khe Sanh had been erected, Johnson vented and bellowed at Acheson. He was determined that the battle for Khe Sanh not repeat the terrible French defeat at Dien Bien Phu. “I don’t want no damn Din Bin Phoos!” he roared. General Westmoreland had told the President that Tet had made the war “a whole new ball game.” The Joint Chiefs wanted 200,000 troops. . . .

For forty-five minutes, Johnson ranted on. As usual, three television sets were blasting away, aides rushed in and out, the phones rang incessantly. Acheson just sat there. Westmoreland’s phrase, “a whole new ball game,” sounded eerily familiar to him; he recalled a cable from another panicked general in Korea: “We face an entirely different war. . .”

When it appeared to him that Johnson was more interested in delivering tirades than seeking advice, Acheson excused himself, walked out of the White House, and returned to his law office at the Union Trust Building across Lafayette Park.

The phone rang immediately; it was Walt Rostow asking why he had walked out. “You tell the President—and you tell him in precisely these words,” Acheson said evenly, “that he can take Vietnam and stick it up his ass.”

This message served to get LBJ’s attention. The President came on the line and asked Acheson, as his President and commander in chief, to return. Though capable of lèse majesté to the individuals who occupied the office, Acheson was deeply loyal to the Presidency; he dutifully walked back across the street to the White House.

But he was still blunt: “With all due respect, Mr. President,” he said, “the Joint Chiefs of Staff don’t know what they’re talking about.” Johnson said this was a “shocking” statement. “Then maybe you should be shocked,” said Acheson. He proceeded to refuse to say anything more until he had been fully briefed. He told Johnson that he wanted no more canned briefings—he wanted “full run of the shop”; he wanted to talk “to the engine-room people.”

One by one, they began appearing at Acheson’s house on P Street in the raw evenings of early March: Phil Habib, a tough-minded diplomat back from two years in Saigon; George Carver, a CIA analyst who had raw intelligence data that had not been first fed through Westmoreland’s fact-massage parlor in Saigon; and General William DuPuy, former Army chief of operations in Saigon who had access to all combat field reports.

Like a senior litigator preparing for trial, Acheson grilled these men like law firm associates, testing their assumptions, pushing deeper and deeper into their files, demanding to see not just summaries but raw data about enemy troop strength and the battle reports of field commanders. Down the long and twisting tunnel he peered, looking vainly for a glimmer of light.

Another Washington lawyer was beginning to ask hard questions that February—the new Secretary of Defense, Clark Clifford.

He had long occupied a peculiar niche within the Establishment. A Midwesterner, Clifford was not Grottie enough to claim membership by right, though in his own mind his comfortable upbringing in St. Louis was every bit as respectable as Dean Acheson’s in Middletown, Connecticut. He was Acheson’s match in confidence and charm, though perhaps slightly too suave and polished. Snobs thought they could smell a touch of snake oil in Clifford’s wavy silver-blond hair, see a little too much sheen in his tailored double-breasted suits. As a lawyer (the highest paid in Washington), he was known not for the quality of his Supreme Court briefs, but for his connections in the federal bureaucracy and on Capitol Hill.

Nonetheless, the real insiders, men like Acheson and Lovett, genuinely liked and respected Clifford. Though they had found him a tad too expedient at times—about Palestine, for instance—they did not doubt his basic integrity. Nor did they hesitate to make full use of his political skills. As Truman’s aide in the late forties, he served, in effect, as an exalted salesman. Working closely and quietly with Acheson, Forrestal, Lovett, and Harriman, he took their policies and made them politically palatable. He became a megaphone that amplified—and sometimes oversimplified—the doctrine of containment. Along the way he absorbed his own clichés. Years later, Clifford recalled his mind-set:

I, like the others, believed in two lessons: one, that neglect led to World War II, and two, that consistent resistance prevented World War III. That, if not in the conscious mind, was my unconscious thought process. So when the war in Vietnam became serious, the feeling was, oh, here we go again. We’ve got to stand up.

Like other Truman-era veterans, Clifford had initial doubts about the war. Unlike most of them, however, he made those doubts clear to the President. In the spring of 1965, as Johnson was deciding whether to send in ground troops, Clifford wrote him that Vietnam could become “a quagmire, without realistic hope of ultimate victory.” Then in July he had again warned, “I don’t believe we can win in South Vietnam. . . . I can’t see anything but catastrophe ahead for our nation.”

Yet once Johnson had ignored this advice, Clifford became an ardent hawk. Like Lovett, he felt that if the U.S. went to war, it had to go all out. Along with his fellow member of Johnson’s Kitchen Cabinet, Supreme Court Justice Abe Fortas, Clifford resolutely urged Johnson to drop more bombs, send in more troops. “The only way to get out of Vietnam is to persuade Hanoi that we are too brave to be frightened and too strong to be defeated,” he told Johnson in January of 1966, arguing in favor of ending a bombing pause.

When Defense Secretary Bob McNamara departed—literally in tears—at the end of February, Johnson looked to his small and dwindling circle of loyalists. Clifford seemed to be the perfect candidate, a Defense Secretary who would heed his commander in chief and vigorously prosecute the war. Johnson overestimated Clifford’s fealty and underestimated his intelligence and independence of mind.

Before installing him at the Pentagon, Johnson charged Clifford with nothing less than a full-scale review of the war. This “A to Z” assessment was precipitated by General Westmoreland’s request for another 200,000 troops. They were not all needed for Vietnam—at least right away—but rather to replenish the military’s depleted ranks around the world. For political reasons, Johnson had resisted calling up the reserves; the Joint Chiefs, by a massive troop request, hoped to force his hand.

An hour after he was sworn in as Secretary of Defense on March 1, Clifford began his own education by having lunch in his private dining room with the Deputy Secretary, Paul Nitze.

The two old Truman veterans had seen each other often over the years around town and at the Metropolitan Club. Nitze knew that he could be forthright with Clifford. He told him that the war could not be won, that the bombing was a total failure, that the war was straining relations with the allies and shortchanging U.S. forces elsewhere. Significantly, while the U.S. was mired in Vietnam, the Soviets were beefing up their nuclear and conventional arsenals. The time had come to wind down the costly sideshow in Vietnam and return to the center stage, facing off the Soviets in Europe. In the short term, Nitze recommended that Westmoreland be given only token reinforcements and that the bombing of the North be halted.

Coming from the drafter of NSC-68, this message had a strong effect on Clifford. It heightened doubts that had been left by a tour of Southeast Asia over the past summer. Clifford had visited Thailand, the Philippines, Australia, and New Zealand—the dominoes that were supposed to topple next if South Vietnam fell—asking these countries to increase their token troop contributions (less than 20,000 men) to the American military presence in Vietnam. He came back empty-handed, “puzzled, troubled, concerned,” wondering whether the domino theory was a meaningful metaphor after all. Fact had not squared with assumption; his lawyer’s mind began to turn.

Around an oval oak table in the Secretary’s dining room, Clifford gathered the Joint Chiefs and his top civilian aides and began asking some probing questions during that first week of March. How long would it take? One year? Five years? Ten years? How many more troops were enough to win: 200,000 more? 400,000? The chiefs could not answer. Clifford found himself thinking, “While I’m in this building, someone is going to want to round it off at a million.” He asked the chiefs, “What is the plan for victory?” There was none. The generals’ hope was to eventually wear out the enemy by attrition. Was there any sign that the Communists were getting worn down? Clifford asked. No, replied the generals.

As an old political operator, Clifford could hardly fail to be impressed by the peace campaign of Senator Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota. Begun as a quixotic gesture by a moody intellectual, McCarthy’s challenge to LBJ for the Democratic nomination had swelled into a children’s crusade. On March 12, McCarthy nearly beat LBJ in the New Hampshire primary, sending a deep shudder through the party ranks.

Clifford’s political instincts were piqued not just by the roar of protest in the streets, but by the quiet discouragement of congressional hawks. Two Senate Armed Services Committee stalwarts—Henry Jackson of Washington and John Stennis of Mississippi—privately told Clifford that they had given up on the war; it was hopeless.

Insider Washington was restless, riled by leaks. The most serious came, ironically, from the ultimate bastion of secrecy, Skull and Bones. At a Bones reunion at Congressman William Moorhead’s house in Georgetown on March 1, a Pentagon dove, Air Force Under Secretary Townsend Hoopes, told his clubmate, New York Times reporter Edward Dale, that the Administration was considering a massive troop increase. After some further digging, the Times broke the news: “Westmoreland Requests 206,000 More Men, Stirring Debate in Administration.” When word of the story reached the Washington elite assembled at the Gridiron Club dinner on March 9, “it moved like wind through a field of wheat,” recalled Times reporter Hedrick Smith. More bitterly, Walt Rostow remembered that “the story churned up the whole Eastern Establishment.”

Meanwhile, Clifford’s doubts about the war had intensified. “As time went on,” he recalled, “my desire to get out of Vietnam went from opinion, to conviction, to passion. I was afraid that we were never going to get out. We were losing thousands of men and billions of dollars in an endless sinkhole. If I ever knew anything, I knew that: we had to get out.”

By mid-March—only two weeks after he had taken the job as Defense Secretary—Clifford found himself unable to defend Administration policy on Capitol Hill. Asked to testify before the Foreign Relations Committee, he begged off, insisting that he was “still learning.” It fell to Paul Nitze, his number two, to take his place. But Nitze refused. He coupled his refusal with a letter to the President offering to resign. Clifford managed to dissuade him from quitting, but Nitze was from then on cut out by the Johnson circle, never again invited to a Tuesday lunch.

Having convinced himself, Clifford began the arduous job of trying to persuade the President. This task was to require all of his wiles, as well as considerable courage. It would cost him his twenty-year friendship with Lyndon Johnson.

Clifford’s transformation came as a tremendous relief, though not a total surprise, to Averell Harriman. Harriman had felt that Clifford, like Acheson, could be made to see reality once confronted by hard facts. After so many years as the only dove among the old Cold Warriors from the Truman days, Harriman could sense that his loneliness was coming to an end, that his old colleagues were slowly coming over to his side. He was encouraged when Jack McCloy sent him a copy of a speech he had given that winter in Chicago, chastising the Administration for losing sight of the “primacy of Europe” in its obsession with Vietnam. “I wish you could take a hand in settling Vietnam,” Harriman wrote McCloy. “It is a frustrating business.”

Harriman welcomed conversions from hawk to dove. But he was not seeking to foment public rebellion against the President, by any means. His correspondence with Bobby Kennedy, whose opposition to the war was becoming increasingly outspoken and whose political ambitions were rising, was highly cautionary. The old politician/statesman feared that if Kennedy became a renegade he would just polarize the Democratic Party and upset the delicate effort to prod Johnson toward a negotiated settlement of the war. “Vietnam is not easy,” he had written Kennedy in February. “It is one of the toughest and most elusive situations we have ever been in. It is not difficult to be critical, but it is difficult to devise a route to an acceptable conclusion. I am all for stopping bombing if the other side will enter talks.” He added a handwritten note: “We are going through a strange and tough experience in Vietnam. I am keen to discuss it with you. Ave.”

But to Harriman, the real quarry was Acheson. He believed, correctly, that Johnson regarded Acheson as the embodiment of American foreign policy since World War II. If only Acheson could be made to see the error of the war, and to privately but firmly convey his change of heart to Johnson, then the President would surely be shaken—enough to begin a search for a political settlement. Once he really began thinking in terms of negotiated peace, Harriman hoped, the President would have to turn to his most experienced negotiator and authority on diplomatic initiatives toward Hanoi—Averell Harriman.

But first Acheson had to be convinced. Their discussion in December had left Harriman surprised and encouraged. During the winter, he had stopped by at P Street several times to stir his old schoolmate’s doubts. “We are in a tough moment in Vietnam,” he wrote Acheson right after Tet. “Keep an open mind.”

When Acheson revealed to Harriman his blowup with the President at the end of February and his demand to learn the facts about the war, Harriman was naturally delighted. He knew as well the nature of Acheson’s briefings, and that the old hawk’s re-education was making him more dovish by the day. Here was the opening, the chance to swing his heaviest gun to bear on the President. On March 7—barely a week after Acheson’s run-in with Johnson—Harriman called Acheson to badger him to return to the White House and express his newfound doubts about the war to LBJ. He sounded a little like big brother trying to goad little brother to jump off the high dive:

HARRIMAN: Have you been called yet?

ACHESON: No, I haven’t.

HARRIMAN: Aren’t you going to offer?

ACHESON: No, he’s spoken two times about seeing me.

HARRIMAN: You don’t want to call Marvin Watson [the President’s appointments secretary] to say you are available?

ACHESON: No, I don’t particularly want to shove myself. If he really wants me, he would remember it, don’t you think?

HARRIMAN: Well . . . I reluctantly say yes.

ACHESON: If he thinks I’m an eager beaver it wouldn’t be quite as effective. I want to wait a little while. If he doesn’t do anything I’ll talk to Dean Rusk about it.

Harriman and Acheson began discussing, cryptically, their contacts with some other pillars of the Establishment. The conversation, which Harriman recorded and had transcribed for his files, has a faint whiff of conspiracy:

HARRIMAN: All I can say is that a good deal of thought is going into things and that’s all to the good.

ACHESON: I saw John Lodge [former State Department official and Cabot’s brother] today and he tells me he’s working on a memo to the President.

HARRIMAN: I have talked to your former law partner [Paul] Warnke [Assistant Secretary of Defense] and I’m going to see Paul Nitze, but I gather everyone is giving things a careful look. It may be that you’ll get called.

ACHESON: Cabot [Lodge] has an office somewhere near you. Have you seen him?

HARRIMAN: Yes, we talked some weeks ago.

Acheson had not quite completed his tutorials. Phil Habib, one of the Saigon veterans who would make the evening trek to P Street to brief Acheson, recalled, “I sensed that he wanted to dig deeper.” Habib showed Acheson his own evaluation of Tet, one that was a good deal more pessimistic than the Administration’s claim that Tet had been a massive defeat for the North Vietnamese. Tet “was costly to the enemy and it did not succeed,” Habib wrote, “but we paid a high price. . . . Old optimism is giving way to new doubts. . . . In many ways Tet is a new ball game in Vietnam. We were winning; steadily if not spectacularly. Now the other side has put in a lot of players and scored heavily against us. We did not win a victory’ despite the losses inflicted on the enemy. The Tet offensive was a serious setback.” Habib concluded that the situation was “far from hopeless,” but that the U.S. would not be able to “recoup losses in the foreseeable future.”

It was the battle reports from the field commanders that had the deepest impact on Acheson, his son, David, recalled. They conveyed to him an impression of suicidal determination by the enemy, and of confusion and low morale on the American side.

Acheson’s study of the Vietnam War had paralleled his research of his own handling of the Korean War for his memoirs. Just as he was trying to decide what he should advise Lyndon Johnson to do about Vietnam, he was coming to grips with General Marshall’s “strange quiescence” before MacArthur’s mad plunge to the Yalu, and his own failure to warn the President before it was too late. The two strands of research intertwined: Acheson vowed not to make the same mistake twice.

The call from the White House came a few days after the conversation with Harriman. Could Acheson have lunch with the President on March 14?

He was kept waiting until 2 P.M. Finally the President appeared and launched into one of his soliloquies. Yes, the U.S. had taken a serious knock, but “Westy” and the Joint Chiefs were optimistic. If they could just get some patchwork replacements, they would be all right.

Acheson listened skeptically. “Mr. President,” he finally cut in, “you are being led down the garden path.” He told Johnson that he needed to hear more facts and less uninformed opinion. Personally, he did not believe much of what was reported by the military because it fluctuated so between optimism and pessimism. For instance, he gravely doubted Westy’s estimate that he had killed or captured sixty thousand “Viet Minh” (Acheson still used the 1950’s term) during Tet. Westmoreland reminded Acheson, he told Johnson, of Civil War General George McClellan, who had finally been relieved by Lincoln after nearly destroying the Union Army.

The real question, said Acheson, was whether the South Vietnamese could be made strong enough to fight their own war. If not, then Johnson would have to look for a “method of disengagement.” Acheson doubted (and Harriman would have been sorry to hear this) that negotiations would be the answer. Hanoi was not interested in anything less than total control over South Vietnam. But Johnson had to learn this for himself—he had to stop talking to the generals and to Rostow and reach down farther into the ranks—as Acheson had done. Acheson even volunteered to supply him with names.

At that moment, Walt Rostow, the National Security Adviser, entered the room. Johnson asked Acheson to summarize his conclusions for Rostow. “Walt listened to me with the bored patience of a visitor listening to a ten-year-old playing the piano,” Acheson recorded in a memo he wrote for his files.

“I have completed the second stage (High School) of my Vietnam education—a most remarkable one, from a rare and probably unsurpassed faculty—which has confused some of my early simple conclusions and shown the difficulties to be even greater than I thought,” Acheson wrote a friend that evening. He was not quite ready to advise the President to disengage from Vietnam—his suggestion for now was a holding action while the President tried to learn more of the facts about the true state of the war. But Acheson’s valedictory was not far off.

Lyndon Johnson saw even his old friends turning against him. On March 14, the same day Acheson told the President he was being “led down the garden path” by the military, he received an eight-page memorandum from Arthur Goldberg proposing a total bombing halt. Goldberg was an old ally; Johnson had made him U.S. ambassador to the U.N. To Johnson, Goldberg’s defection from the war effort came as a personal betrayal.

“Let’s get one thing clear!” he stormed at his advisers. “I’m telling you now that I am not going to stop the bombing! Now I don’t want to hear any more about it. Goldberg has written me about the whole thing, and I’ve heard every argument, and I’m not going to stop it. Now is there anybody here who doesn’t understand that?”

At the Tuesday lunches, Johnson watched Clark Clifford transform from stout warrior to brooding doubter. James Rowe, a Washington lawyer and Johnson’s most trusted political adviser, bluntly told the President that he had nearly lost the New Hampshire primary to Eugene McCarthy on March 12 because he had become the war candidate, and the country no longer cared about winning the war. “Everybody wants to get out,” Rowe bluntly told Johnson. “The only question is how.”

Then, in the Ides of March, Johnson realized his worst dread: on March 16, Bobby Kennedy announced that he would challenge him for the Presidency.

Johnson could not sleep. His face was ashen, his eyes sunk and bleary. Folds of flesh hung down from his cheeks. Angry red sties began to pop out along his raw eyelids. He lashed out.

“We shall and we are going to win,” he angrily declared to a meeting of businessmen on March 17. The next day he shrilly told a group of farmers, “The time has come when we ought to stand up and be counted, when we ought to support our leaders, our government, our men, and our allies until aggression is stopped, wherever it has occurred.”

In his gruff avuncular way, Harriman admired Robert Kennedy. Under different circumstances, perhaps, he would have backed him for President. But Harriman still patiently hoped that if he showed his loyalty and steadiness to Johnson, he would be rewarded with responsibility.

RFK, who had given his son Douglas the middle name of “Harriman” in honor of Averell, called the old statesman after declaring on television that he would challenge Johnson for the Democratic nomination. The conversation was vintage Harriman:

KENNEDY: I’m running for President.

HARRIMAN: Next time tell the children to smile. Ethel looked great. The kids looked bored.

KENNEDY: They were.

HARRIMAN: I don’t expect to have a press conference soon, but if it does come around I’m going to support the President.

Clifford watched Johnson’s flailing with growing discouragement. He felt that the President was just getting more hawkish, despite the counsel of his closest friends. Briefly, he considered joining other civilian doves at the Pentagon in a mass resignation. But listening to Johnson rant at a Tuesday lunch on March 19, he had another idea. As casually as possible, he suggested that perhaps the President would like to reassemble the Wise Old Men, the group that had been so calm and reassuring about the war back in November. Johnson, without hesitation, agreed.

Like all Clifford moves, this was a highly calculated one. He had been checking around town, taking readings at the Metropolitan Club and the Gridiron dinner, making a few phone calls to New York to sample the mood at the Council on Foreign Relations and on Wall Street. He knew exactly what Acheson was thinking because he had made a point of going to see him privately at his home on P Street and telling him of his own opposition to the war. “I told him of my agony, in detail, so he might get the feel of it,” Clifford later recalled. In return, Acheson revealed his own doubts.

By now, Acheson’s education was complete. His last required reading came not from Habib and the other government briefers, but from an old newspaper friend, Wallace Carroll, a former New York Times reporter who had become editor of the Winston-Salem (N.C.) Journal and Sentinel. In mid-March, Carroll had sent Acheson a copy of a full-page editorial he had written called “Vietnam Quo Vadis,” outlining why in his view the U.S. had to withdraw from Vietnam. Late on a Saturday night, March 23, Acheson called Carroll: “Wally, I’ve been dragged through the bureaucracy and nothing makes sense. Why is it that a guy from Winston-Salem can put all the facts together?” He told Carroll that he had read Ambassador Bunker’s and General Westmoreland’s cables, and then the field reports. He was convinced that Tet was a disaster. “What really surprised me when we got into the whole question of Vietnam was that there was no political base on which to build,” he said. The South Vietnamese were hopeless allies; it was time to begin an orderly disengagement. He told Carroll that he was going to the White House on Monday for a meeting on the war with other elder statesmen. Could he please send up twelve copies of the article? Wondering whether Acheson had ever heard of the Xerox machine, but eager to be of service, Carroll mailed the copies special delivery.

The next morning, Lucius Battle, Acheson’s former assistant, ran into his ex-boss in the driveway at Johnson’s Flower Center on Wisconsin Avenue above Georgetown. Though dressed in well-worn work clothes and clutching a flowerpot, the former Secretary of State, his mustache clipped, his bearing dignified and erect, still struck a magisterial pose. He stuck his head through Battle’s open car window.

“I’m going to tell the President we have to get out of Vietnam,” he said simply.

Battle was speechless. The creator of the Pax Americana, the old Cold Warrior who guarded America’s commitments like a sacred trust, wanted out. To Battle, who knew well Acheson’s pragmatism and ability to face hard reality, the decision was not altogether surprising. Nonetheless, he could not help but feel, as he watched the champion of the Western Alliance cradle his geraniums, that an era had passed.

It is not likely that Acheson himself sensed that he had crossed some great divide, that he had developed a sudden awareness of the limits of U.S. power and an appreciation of the forces of Third World nationalism. George Ball believes that Acheson approached Vietnam from a narrow, lawyerly point of view. “When the Supreme Court wants to make new law,” said Ball, “they rarely come out and say so. They distinguish, rather than overrule, precedent. I think this is what he did on Vietnam.” Recalled McGeorge Bundy: “Acheson was resistant to philosophical questions. He liked to quote Holmes that ‘life is action.’” Said Clifford: “I don’t think Acheson changed his philosophy about America’s role in the world. Rather, he was always a realist.”

If anything, Acheson felt he was acting to preserve the world order he had helped create, not change it. In a sense, Acheson was returning to basic principles. He was an Atlanticist. Europe, he had always believed, was the world; Vietnam was a diversion. A war without end was too high a price to pay for South Vietnam’s freedom, especially since the South Vietnamese were so incapable of defending it themselves. A year later, at a party at Joe Alsop’s, Acheson got into an argument with Walt Rostow about the strategic importance of Asia. Rostow insisted that Acheson must have believed at one time that America had to maintain a forceful presence in the region; why else intervene in Korea? “The only reason I told the President to fight in Korea,” Acheson snapped back, “was to validate NATO.” Bitterly, Rostow concluded that Acheson had decided that another year of war was “too much blood to spill for those little people just out of the trees.”

Acheson was talking to Mac Bundy about Vietnam that March, and the younger man was in synch with the older. In Bundy’s analytic mind, “the twin curves of patience and progress had intersected,” i.e., the country was not willing to make the sacrifice necessary to win a prolonged war. In a carefully worded talk at Harvard in mid-March, the former National Security Adviser had begun to express publicly some of his concerns; the Crimson immediately blared, “Bundy Opposes Escalation.” Actually, Bundy’s doubts had been growing for some time. Despite his “light at the end of the tunnel” speech at the November Wise Men meeting, he had written Johnson a troubled letter ten days later questioning Westmoreland’s “search and destroy” strategy and wondering if the time had not come to second-guess the military’s conduct of the war. By March, Bundy was, in private at least, in full dissent; he wanted to find a way out of Vietnam.

Once more they were gathered, the Wise Old Men, the elder statesmen, or as some members of the press had begun less reverently describing them, “the Usual Suspects.” The group that assembled at the State Department for briefings on the afternoon of Monday, March 25, was the same that had met with the President in November with two additions: Cyrus Vance, former Deputy Secretary of Defense and a sometimes troubleshooter for Johnson; and General Matthew Ridgway, the able soldier who had turned around U.S. forces in Korea after the disaster at the Yalu. Once again, McCloy and Lovett were absent. (McCloy, at least, was watching from the shadows; he had had lunch with Averell Harriman earlier that day.)

The Bundy brothers, greeting the Wise Men at the State Department, felt the need to prod them a little, to make them probe the substance of the briefings, to ask hard questions. At earlier such sessions, the elder statesmen had been “rushed down on the shuttle, without time to read,” Bill Bundy recalled. “We fed them too well, and everyone would have one more drink than is useful for really hard thinking in the night.” This time, the Bundy brothers, along with Under Secretary of State Nicholas Katzenbach, urged the Wise Men to read carefully the documents that had been assembled for them in a small library in the State Department that afternoon. In the evening, they were instructed to assemble on the eighth floor for dinner and a formal briefing.

It was possibly the most distinguished dinner party of the American Establishment ever held. The Cold War Knighthood, now bowed and balding but nonetheless formidable, sat down together to dine by candlelight and discuss the Vietnam War, the culmination of America’s commitment to stopping aggression anywhere in the world. In quiet tones, they began to talk to one another about how that commitment might be curtailed.

Though they perhaps did not realize it, the Wise Men were meeting at the high-water mark of U.S. hegemony. Never again would America’s global commitments extend so far. After this evening, the U.S. would begin to slowly and painfully pull back, to recognize the limits of its power. These men were about to play a critical role in reversing the momentum that they had done so much to generate over the last two decades. Though few were conscious of it, they were at one of history’s turning points.

The moment was as significant for their role in America as it was for America’s in the world. By dismantling their own creation, they were as well diminishing their own raison d’être. Never again would a President put such faith in the collective wisdom of the Establishment. For the Wise Men, this dinner was, in a sense, the last supper.

The President, who was not scheduled to meet formally with the group until the next morning, dropped by during the meal, shook hands all around, like a congressional candidate at a fund raiser, and left to go pick bombing targets in the White House Situation Room. After dinner, the group repaired to the State Department Operations Center on the seventh floor, where they were briefed by Habib of State, Carver of the CIA, and General DuPuy—Acheson’s instructors for the past month.

Habib could tell which way the Wise Men were moving by their questions. “Do you think a military victory can be won?” asked Clark Clifford, who had come in his dual capacity as Defense Secretary and elder statesman. “Not under present circumstances,” replied Habib. “What would you do?” Clifford asked. “Stop bombing and negotiate,” he answered truthfully. Ambassador Goldberg was skeptical about General DuPuy’s claim that 80,000 of the enemy had been killed during Tet. He asked DePuy what the normal ratio of killed to wounded was. “Ten to one; three to one conservatively,” he answered. Goldberg asked how many VC were in the field. “Two hundred thirty thousand,” answered DuPuy. Goldberg did some quick arithmetic and determined that by conservative estimates they were now all in the hospital. “Then who the hell are we fighting?” he demanded.

A few, like Douglas Dillon, were deeply affected by the briefings. “In November, we were told that it would take us a year to win,” he remembered. “Now it looked like five or ten, if that. I knew the country wouldn’t stand for it.” Others had come to the meeting with their minds already made up. “I could sense that the country was being torn up,” recalled Vance. “We had to find a way out.”

The meeting broke up toward 11 P.M. The old men looked somber as they filed out, George Ball recalled. “I was delighted,” remembered Clifford; the questions and answers had been even more pessimistic and gloomy than he had dared hope.

“I smelled a rat,” recalled Walt Rostow. “It was a put-up job.” As Rostow, who had come to the dinner as Johnson’s emissary and observer, listened to the downward drift of the discussion, he sensed the demise of an institution he had long yearned to join, and now felt bitterly disappointed in. “I thought to myself,” he recalled, “that what began in the spring of 1940 when Henry Stimson came to Washington ended tonight. The American Establishment is dead.”

Around a green baize table in the Operations Room of the State Department, the Wise Men convened again the next morning to discuss among themselves their conclusions. For many, the doubt of the prior evening had crystallized overnight into conviction: the U.S. must begin the process of disengagement from Vietnam.

“There must have been a mistake in the invitation list,” Ball thought to himself. He could hardly believe what he was hearing from a group of such heretofore stalwart hawks. Neither, perhaps, could the new converts themselves. “There was a sense of shock,” recalled Ball, “of people who had not expected to say what they were saying.” Not everyone had made the switch. General Maxwell Taylor was appalled and “amazed” at the defection. “The same mouths that said a few months before to the President, ‘You’re on the right course, but do more,’ were now saying that the policy was a failure,” recalled Taylor. He could think of no explanation, except that “my Council on Foreign Relations friends were living in the cloud of The New York Times.”

The President finally heard the Wise Men in the Cabinet Room at 11 A.M. He had spent the morning getting bucked up by the generals. JCS Chairman Wheeler and General Creighton Abrams, who was slated to succeed Westmoreland as commander in Vietnam, had sought to minimize the damage of Tet. Now, the President summoned General Wheeler into the Cabinet Room and asked him to repeat his upbeat spiel to the Wise Men.

The U.S. was “back on the offensive,” Wheeler reported. True, President Thieu had said that the South Vietnamese “could not take another Tet offensive,” but Westmoreland had “turned this around.”

Watching the dour faces around the table, Rostow concluded that the Wise Men “weren’t listening.” In fact, they were listening, just not believing. When Wheeler proclaimed that “this was the worst time to negotiate,” Cabot Lodge leaned over to Acheson and whispered in his ear, “Yes, because we are in worse shape militarily than we have ever been.”

At lunch, Johnson dismissed everyone but the Wise Men. He wanted to meet alone with them. Though government officials—Rusk, Rostow, CIA Director Helms, Paul Nitze, Goldberg, Katzenbach, Bill Bundy—had been present at all the earlier sessions, they were not invited to this one.

There was, however, one exception to the rule: Averell Harriman. Told that he was not invited to the luncheon meeting with the President, since he was a State Department official, he simply invited himself. No place had been set for him; when he arrived, the White House stewards had to add an extra one.

Harriman did not come to speak, but rather to watch and listen. While the Wise Men were facing up to the futility of military victory that he had recognized long before, Harriman was quietly pursuing his own separate agenda—persuading Johnson to bring Hanoi to the peace table.

The day before, a headline had appeared in The New York Times: “Harriman Head of Johnson Committee.” The former governor had assembled a group of influential New York Democrats to back the President against the McCarthy and Kennedy challenges. Though Harriman was genuinely loyal to the President, he did not have LBJ’s re-election foremost in mind when he organized the committee. He was, rather, picking up an old-fashioned political IOU.

Johnson went for the bait. As Harriman sat listening to the Wise Men hold forth in the Cabinet Room, the President slipped him a note. “Averell—thanks so much for your help,” it read in Johnson’s handwritten scrawl, “and most especially your aid in New York.”

Harriman remained silent throughout the lunch. Afterward, however, he immediately wrote a note to LBJ. “From reports I gather New York, like Vietnam, is a bit soggy,” he began gruffly. Then he got to the point: ever so gently, he reminded Johnson that he stood ready to negotiate with the North Vietnamese “when you think the time is right.”

At the lunch with the President, Mac Bundy, the youngest Wise Man, reported on the group’s earlier deliberations and summarized its views. There had been a “significant shift” since the last meeting of the Wise Men in November, he told the President. Acheson had best stated the new majority view at their meeting that morning when he had remarked, “We can no longer do the job we set out to do in the time we have left, and we must take steps to disengage.”

Acheson, sitting erect at the President’s right hand, spoke up. By late summer, he flatly declared, the U.S. had to begin the process of withdrawal.

Acheson’s voice was firm, clear, and unemotional. His language was spare and to the point. He showed none of the rhetorical flourishes, none of the passion that he had flashed on a February morning twenty-one years before, when he had taken the White House floor to plead that unless the U.S. supported Greece and Turkey, the Communist infection would spread from one country to the next, like rotten “apples in a barrel.”

Johnson went around the table soliciting comments, but the dominant force was Acheson. When Abe Fortas, who remained hawkish, protested that Bundy’s summary did not accurately represent the group’s view, Acheson cut him off. “It represents my view,” he said.

At one point, General Wheeler, whom Johnson had asked in to take questions, took exception to Acheson’s characterization of the Pentagon as “bent on military victory.” Not so, said Wheeler. He realized that a “classic military victory” was not possible. Acheson regarded him coldly. “Then what in the name of God do we have five hundred thousand troops out there for?” he inquired. “Chasing girls?”

“Can no longer do job we set out to do,” Johnson jotted on a note pad, underlining vigorously for emphasis. “Adjust our course. Move to disengage” His grandson, Lyn Nugent, came in and curled up on his lap, as he had during the Wise Men meeting the prior November. No one, however, not even a grandson whose middle name was Lyndon, could have comforted Johnson that afternoon.

One can imagine how he felt, surrounded by the Establishment he envied and resented, with Acheson leading the way, ripping up the roots of U.S. involvement, telling him, in effect, that the era of global containment was over. “They were intelligent, experienced men,” Johnson wrote in his memoirs. “I had always regarded the majority of them as very steady and balanced. If they had been so deeply influenced by the reports of the Tet offensive, what must the average citizen be thinking?”

Johnson was not ready to capitulate quite yet, however. When the meeting broke up, he grabbed a few of the stragglers and began to rant. “Who the hell brainwashed those friends of yours?” he demanded of George Ball. He stopped General Taylor. “What did those damn briefers say to you?” Johnson went so far as to demand to hear the same briefings the Wise Men had received. Carver and DuPuy dutifully repeated theirs, but Habib, the most pessimistic briefer, left town. (Rostow let him go, figuring he had done enough damage.) “Tell me what you told them!” Johnson bellowed. They did; Johnson just shook his head. “I don’t know why they’ve drawn that conclusion.”

Clifford’s exhilaration after the Wise Men meeting quickly dimmed. The President seemed just as bellicose as ever. He was scheduled to give a major address on the war on March 31, but as the speech moved through several drafts, Johnson continued to insist on unyielding rhetoric. There was no mention of negotiation or de-escalation. Reading over the latest version at a drafting session on March 28, Clifford could bear it no longer. “The President cannot give that speech!” he burst out, losing his customary poise. “It would be a disaster! This speech is about war. What the President needs is a speech about peace! The first sentence reads, ‘I want to talk to you about the war in Vietnam.’ It should read, ‘I want to talk to you about peace in Vietnam.’”

Clifford anticipated resistance from his hawkish opposite at State, Dean Rusk. The two Secretaries had sparred increasingly over the past month, not with raised voices but with a perceptible edginess. Yet to his surprise, Rusk offered no opposition to Clifford’s moderating suggestions.

Rusk’s role in these critical weeks has long been obscure, but it was essential. Privately, this self-effacing veteran of the Truman era had as much impact on the President as the Wise Men.

After more than seven years as Secretary of State, the round-faced Georgian remained inscrutable, a mystery to even his closest associates. Unable to know him, they came to regard him as a two-dimensional figure, a cardboard cutout of his idol, General Marshall. He seemed locked in clichés: he feared—despite all evidence to the contrary—that the Chinese were about to pour over the Vietnamese border at any moment, as they had over the Yalu in 1950. (Asked what the stakes were in Southeast Asia he had replied ominously, “A billion Chinese armed with nuclear weapons.”) Recalling that the U.S. had stood fast in Korea and fought back the Nazis and Japanese in World War II, he was stoical. He was as well a tireless worker who sacrificed his family life to his job, though on Saturday afternoons he could sometimes be found in his office watching old war movies. (Rusk liked to see John Wayne take on the Japs; it seemed to remind him of a time when the enemy was seen clearly and the whole country was behind the war effort.)

Though an adopted member of the Establishment, Rusk continued to regard himself as an outsider. He was suspicious of the heavy East Coast/Wall Street tilt of the Wise Men; back in 1965, he had urged LBJ to include more southerners, westerners, and academics in the group. He held himself aloof, he explained to Chip Bohlen, not just because General Marshall had, but because “I’m a dour man from Cherokee County, Georgia—such people just don’t talk very much about the things they feel most deeply.” He considered it a “compliment” that he was the only Cabinet member that President Kennedy called by his last name. “I was never part of the Hyannis Port, West Palm Beach environment, was never pushed into Ethel Kennedy’s swimming pool, never played touch football,” he wrote Bohlen in 1973. “None of this detracted from my deep commitment to the President himself.”

Rusk preferred to operate secretively, to confide only in the President, and no one else. Thus it is not surprising that Clifford did not know that Rusk was, in a sense, ahead of him in pushing LBJ toward a peace initiative.

Clifford believed that his only true ally in the inner circle was a Johnson speech writer, Harry McPherson, who had become a committed dove and was trying almost desperately to sway the President. What Clifford did not know was that on March 25 —before the Wise Men meeting—Rusk wrote Johnson, “My own mind is running very close to that of Harry McPherson about a possible peace move.” By the time of Clifford’s impassioned appeal on the twenty-eighth, Rusk had already gone a long way toward persuading Johnson to declare a partial halt to the bombing of North Vietnam.

In fact, Rusk had suggested a partial halt as early as March 4—and in Clifford’s presence. At the time, Clifford and the other doves in State and Defense had regarded Rusk’s suggestion as a cynical gambit. They believed that Rusk was trying to con the American public with a bait-and-switch, aimed at rebuilding public support by halting bombing for a few months—during Vietnam’s rainy season, when it was ineffective anyway—before once again escalating the conflict.

But Rusk was not a cynic. He hated the war and badly wanted to find a way to end it. He was skeptical about bringing the North Vietnamese to the bargaining table, but he believed, as he later put it, that “you’ve got to try everything.” He recalled some long-shot diplomatic forays that produced results, specifically Kennan’s secret mission to Malik to open peace talks on the Korean War in the spring of 1951.

Johnson trusted Rusk more than anyone. The Secretary was so slow, deliberate and cautious that Johnson could count on him to give careful, thoughtful advice. He accepted Rusk’s argument that it was time to give diplomacy a chance with a partial bombing halt, as LBJ reasoned in his folksy way, “Even a blind hog sometimes finds the chestnut.”

Johnson, in his terrific agony, had another, far more shocking announcement than a bombing halt in mind. By now he was devoting himself entirely to the war effort; the “Bitch War” of his nightmares had consumed all else, even his political ambition. He wanted to do something dramatic, to make a gesture that would show his absolute resolve to bringing the war to an honorable end. He decided to announce that he would not run for a second term in the White House.

The decision not to run again had actually been building for some time. Over the past year, he had told Lady Bird, Rusk, Rostow, and George Christian, his press secretary, that he did not want a second term, that he feared that he would end up like Woodrow Wilson, bedridden and too sick to govern. Now he saw a chance to couple his desire to leave office with a noble cause, the conclusion of a war that threatened to wreck his Presidency and tear apart his country.

“So tonight, in the hope that this action will lead to early talks, I am taking the first step to de-escalate the conflict,” Johnson told the national television audience on the evening of March 31. “We are reducing—substantially reducing—the present level of hostilities. And we are doing it unilaterally, and at once.” Then he delivered his shocker: “I have concluded that I should not permit the Presidency to become involved in the partisan divisions that are developing this political year. Accordingly, I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your President.”

Most Americans fastened on this last sentence of his speech. One, however, was more moved by an earlier line. After making a plea to the North Vietnamese to enter negotations, he announced, “I am designating one of our most distinguished Americans, Ambassador Averell Harriman, as my personal representative for such talks.”

Less than a week later, Hanoi accepted LBJ’s invitation to talk. On April 3, the North Vietnamese announced that they were willing to meet with U.S. representatives to discuss peace negotiations.

For Harriman, the waiting was over; his patience and doggedness in pursuit of negotations and Lyndon Johnson had been simultaneously rewarded. No longer would his peace plans be filed away unread. As Harriman knew he would, the President had despaired of a purely military victory and turned to diplomacy. And because of his experience and wisdom, not to mention patient scheming, Harriman was to be chief diplomat.

As the veteran of dozens of tedious and often fruitless negotiations, he was not the sort to be euphoric about the mere willingness to talk, however. He knew the severity of the task ahead. For one thing, the North Vietnamese had not agreed to negotiate a settlement but rather to discuss conditions for entering settlement talks. In essence, they had only agreed to talk about talking. Secondly, as Harriman well knew, Johnson would not give up much on the battlefield to get more promises from Hanoi.

Harriman’s doubts were confirmed when he received his negotiating instructions. Flying by helicopter to Camp David on April 9 (the last time he had been to the President’s Maryland retreat it was called Shangri-La and FDR was his host), Harriman was discouraged by his meeting with LBJ and his advisers. His instructions, recalled his aide Dan Davidson, “were basically, ‘you stay there until they surrender on our terms.’” Only Clifford backed his argument for flexibility in dealing with the North Vietnamese. “There is no doubt that Clifford’s initiative saved the instructions from mutilation,” Harriman wrote in a memo to files. “The Secretary of State did not make any contribution.”

The emnity between Harriman and Rusk was by now deep and irreversible. “Averell simply didn’t believe that a second-rater like Rusk should get the job that was more rightfully his,” a colleague of both men later said. “What is worse, he was indiscreet about it.” Harriman would scoff among friends that Rusk was paralyzed by the past, frozen forever in December of 1950. Inevitably, his remarks got back to Rusk. The Secretary, who believed in orderly procedure and the chain of command, was naturally reluctant to have an independent sovereignty like Harriman floating about his department, doing as he pleased. Rusk sought whenever possible to keep him under tight rein.

Harriman’s loyalty was to the President. “I will obey orders,” Harriman told LBJ over the telephone on April 11. “I hope so,” said Johnson. “I am a soldier,” Harriman re-emphasized. “I will obey orders.”

To make sure, Johnson decided to appoint another negotiator to accompany Harriman to the peace talks. He chose Cyrus Vance, a man of the Establishment who also had close ties to Johnson.

The President seemed to like the fact that Vance was a West Virginian, a country boy like him. In fact, Vance was the favorite nephew of John W. Davis, a West Virginian who was for several decades the most powerful lawyer on Wall Street. Vance had gone to Yale (where he had been a member of Acheson’s secret society, Scroll and Key) and on to Wall Street. He had formed ties to Johnson by working as a Senate legislative counsel in the fifties, and LBJ had made him Deputy Secretary of Defense in 1964. A bad back, his children’s tuition bills, and growing private disillusionment with the war forced him to leave the Pentagon in 1967, but he had continued to serve the President as a very effective troubleshooter during the Detroit riots. He was staying at the White House during the April 1968 riots in Washington when LBJ asked him to serve as Harriman’s partner at the peace talks.

“I want to condition Harriman’s mind to the fact that it is joint with Vance,” Johnson told Rusk and Clifford. The President bluntly told Harriman that, while he was senior in age and experience, Vance was his coequal as a negotiator.

It was widely assumed that Vance was Johnson’s “spy,” sent to keep an eye on Harriman’s dovishness and report back to Johnson when the old statesman strayed from the White House hard line. But if that was to be his role, recalled Vance, Johnson never told him.

It may be that Johnson simply assumed that Vance would be a restraining influence on Harriman; Vance, after all, had been a faithfill, diligent Deputy Secretary of Defense. Johnson did not realize, however, what a dove Vance had become. Though Vance was never in any way disloyal to Johnson, he shortly became not just Harriman’s partner, but his ally.

Harriman also had a strong moral supporter in Acheson. “We are not as young as we once were, but we still pack a wallop,” Acheson wrote Harriman. “You must tell me what Our Leader is up to. I thought for a while that you had him on course, but I gather Bunker and Westy have fed him some raw meat. I don’t envy you bargaining without a goal. Perhaps the Viet Minh will think you’re being inscrutable, a well-known Western characteristic.”