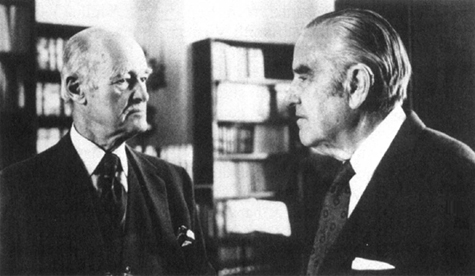

Kennan and Harriman

“Never in

such good company”

By the spring of 1970, the Establishment and its outposts were under siege. At Harvard, students were shouting “Ho! Ho! Ho Chi Minh! Ho Chi Minh is going to win!” In New Haven, Yippie leader Abbie Hoffman vowed to “burn Yale down.” Old Blues anxiously and not unreasonably wondered whether their alma mater would still be standing for reunions in June.

The revolution seeped into the inner sanctum. When it was learned that David Rockefeller, chairman of the Council on Foreign Relations, had offered Bill Bundy the editorship of Foreign Affairs just before the 1970 Harvard-Yale game, many younger members bitterly protested. Word of the appointment came just before the sensational publication of the Pentagon Papers, the Defense Department’s secret internal study of U.S. involvement in Vietnam, which documented Bundy’s role in escalating the war. The epithet “War Criminal” began to be heard even within the paneled chambers of the Harold Pratt House, the Council’s mansion on Park Avenue.

The popular press saw cracks in the firmament; the cover line of a September 1971 New York magazine proclaimed “The Death Rattle of the Eastern Establishment.” A year later David Halberstam traced the tragedy of Vietnam to the hubris of the ruling elite in his bestselling The Best and the Brightest. (Halberstam’s cutting profile of Mac Bundy, published earlier in Harper’s Magazine, “had points which could have been soberly put,” Acheson wrote a friend, “but not by a smarty pants.”

Acheson, the high priest of the old order, found himself in the unfamiliar and not entirely comfortable position of dissent. Although he continued to maneuver discreetly against the war, he did not relish life in the underground, and he began to squabble with his coconspirators, who he felt were becoming too vocal. “Clifford talks too much,” he complained to Harriman at an embassy party; a Washington Post gossip columnist overheard and promptly printed the remark. Acheson had to apologize to Clifford, though he counseled him to follow Gambetta’s maxim to would-be revolutionaries: “Think of it always, speak of it never; hostile ears are listening.” Acheson also thought Harriman was becoming too outspoken, especially after he testified before Congress that “a timetable should be set for withdrawal of all U.S. troops.”

The old rivalry between the former schoolmates, sublimated during the machinations that surrounded the March 1968 meeting of the Wise Men, surfaced again. Acheson “recalled sourly that Averell Harriman from 1965 to 1968 had been a complete hawk on Vietnam,” Cy Sulzberger recorded in his diary, “although, he said, Averell simply does not remember this at all nowadays.” Harriman was just as ungracious about Acheson’s role. “You gave entirely too much credit to Acheson,” he told Townsend Hoopes, whose Limits of Intervention described Acheson’s role in the March revolt. “That was the only time in the entire war that he was right.”

Scruffy, rude antiwar protestors offended Acheson. He wrote a friend that he preferred to use the word “juvenile” to “young” because it is “slightly pejorative.” When his granddaughter Eldie, a student at Harvard Law School, expressed dismay that police were randomly locking up protesters at the May Day demonstrations in 1971, Acheson grumbled that the loss of civil liberties was “a small price to pay (since I was not a victim) for getting troublemakers off the streets for twenty-four hours.”*

Acheson was not likely to remain on the outside with the picketers for long. Henry Kissinger, Nixon’s National Security Adviser, admired the old statesman, and he was determined to make use of his wisdom and experience, even if President Nixon in past incarnations had been Acheson’s mortal enemy. Kissinger himself had worked with Acheson for years; the two shared a realpolitik outlook on America’s role in world affairs. (Kissinger also appreciated his elder’s earthy bluntness. As a graduate student writing a research paper in 1953, he had posed a ponderous question about Acheson’s reaction to a particularly “muscular” dispatch from General MacArthur in Korea. The paragon of old-world diplomacy arched an eyebrow and asked, “You mean before or after I peed in my pants?”)

President Nixon both “revered and despised” the old foreign policy Establishment, Kissinger recorded. But like his predecessors, he could not resist calling on its tradition of service. When he finally came to know Acheson as a person rather than an effigy, he found his directness and acerbity refreshing.

“I am being drawn back without enthusiasm into Presidential consultation,” Acheson wrote a friend. Though he loathed the very idea of Nixon, Acheson was immensely loyal to the office of the Presidency. Even at the age of seventy-six, he missed proximity to power. Indeed, he was so willing to forgive the past to serve in the present that his memoirs, published during Nixon’s first year in office, make no mention of Senator Nixon’s prominent role in the “attack of the primitives.”

Acheson was hardly immune to flattery. “Nixon and Kissinger have been most considerate of me and some of my aging colleagues like McCloy and Nitze,” Acheson wrote Anthony Eden. “They ask for, consider, and sometimes even follow our advice.” He added that the White House had gone so far as to install a secure telephone line to his winter vacation home in Antigua, in the Caribbean. “My hopes for RMN are growing as I see more of him,” Acheson wrote Bob Lovett. “I also find Henry Kissinger’s funereal Germanic manner better suited to responsibility than to mere academic pronouncement. He is, I think, a better influence than either Mac Bundy or Walt Rostow.” Nonetheless, Acheson did not hesitate to let Kissinger know when he was being “particularly ponderous,” Kissinger recalled. “Can I put it this way?” Kissinger asked him once about a heavy bit of prose. “Certainly you can put it that way,” Acheson replied, “but not if you want to get anywhere.”

“Mr. Nixon and I have become friendly, an almost unbelievable possibility,” Acheson confided to a friend in December of 1969. Flabbergasted by this transformation, Alice quizzed her husband one day when he floated home from a session with the President. “Did he flatter you?” she asked sternly. Acheson sheepishly admitted that he had allowed his vanity to be massaged by the attention.

The lovefest could not last. Though Acheson initially backed Nixon’s “Vietnamization” of the war, he fell out when the President widened the war and stepped up the bombing. “I fear his judgment is very bad,” Acheson wrote John Cowles after Nixon ordered the incursion into Cambodia in the spring of 1970. A year later, he wrote Anthony Eden, “The President seems rattled and prone to panicky stupidities.” To Cowles he fumed, “The present Administration is the most incompetent and undirected group I have seen in charge since the closing years of the Wilson Administration.”

Disgusted, Acheson began simply refusing to consult with the President on Vietnam, since his advice was clearly ignored. After his experience with LBJ, he declined to be used as an icon and prop for policies he did not support.

His pride, however, did not stop him from volunteering when the cause seemed just. In the spring of 1971, during the last year of his life, he heard the call again, to stand fast and defend an institution most dear to him, the Western Alliance.

Smarting from its quiescence in Vietnam, no longer willing to be used by Presidents as a passive instrument, Congress in the early seventies had begun to assert itself in foreign policy. The failure of intervention in Vietnam had stirred old isolationist yearnings; liberals and conservatives alike wanted to pull back America’s commitments. In May, Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield, who embodied strands of both dovishness and isolationism, proposed to cut the U.S. troop commitment to NATO in half. Congressional leaders informed the White House that the measure had enough votes to pass.

With his creation in serious jeopardy, Acheson offered his services to Henry Kissinger. When Kissinger suggested that Acheson might talk to a few of his friends, the old Secretary responded, “It seems to me what we need is a little volley firing and not just a splattering of musketry.” He proceeded to recruit a battery of former Secretaries of State and Defense, old High Commissioners for Germany, NATO commanders, and chairmen of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Lovett and McCloy signed on; McCloy even flew to Germany to rally Chancellor Willy Brandt’s support. The old warriors were gathered around Nixon in the Oval Office in an intimidating montage. To Kissinger, watching from the wings, “It was the final meeting of the Old Guard.”

Acheson himself was outraged that Congress should dare to interfere with the foreign policy prerogative of the Executive. “You are the President,” he instructed Nixon. “You tell them to go to hell.” To the press, Acheson described the Mansfield amendment as “asinine” and “sheer nonsense.” (Asked why the meeting had dragged on for several hours, Acheson responded, “We are all old and we are all eloquent.”)

The assault of the elder statesmen shook the Capitol: the bring-the-boys-home initiative was defeated in the Senate by 61-36. Acheson wrote John Cowles:

. . . those of us who rallied to the President’s side have been subjected to a degree of vilification unequaled since the McCarthy days. It has been great fun and resulted in a most satisfying victory. I got a charming note from RMN in which he said that I could now justly claim to have been present at the creation and the resurrection.

It was to be the dedicated warrior’s last hurrah, his final defense of duty and honor in an age that seemed increasingly dominated by expediency. “I think the world not only seems to be going to hell in a hack,” he wrote a friend, “but is actually going there.”

His deteriorating health added to his gloom. He had been hospitalized for a while by a minor stroke, a bad case of the flu ruined a vacation in Antigua, and a thyroid condition left him with double vision. “Every croquet wicket is two,” he complained to Anthony Eden. Far worse for a man whose life had been shaped by a sense of the power of words, reading became almost impossible at times.

Acheson sensed that his era was passing, and he did not much like what he saw was taking its place. “We are now in a period where there are mediocre men everywhere,” he lamented to Cy Sulzberger. “People have opinions but no knowledge, and leaders are made in the image of the masses. Democracy is only tolerable because no other system is.”

Mediocre men. Throughout his life, he could never contain his scorn for mediocrity. And so, as his life grew to a close, he began to reminisce affectionately about a man who, though sometimes maddening or puzzling, was decidedly not mediocre. That September, Acheson sat down at Harewood and wrote to the childhood friend who had been a trusted companion, and an occasional rival, over life’s long course.

They had met, Acheson recalled, “66 years ago this month,” as schoolboys at Groton. “In most of those years that have passed we have joined in activities that sometimes have been pretty strenuous, first of all on the water, where we rowed, and later in government, where we struggled.” There had been failure as well as success, dark days as well as moments of triumph, but they had gone through them together. “The first time I was ever fired I was in company with you,” Acheson noted, referring to their dismissal as Yale crew coaches. “I have been fired since and so have you. I hope we can both say, ‘never in such good company.’”

It was Averell Harriman’s loyalty that Acheson valued above all. Theirs had been a time when a small group of men, whatever their disagreements, felt secure in trusting the fealty of their friends. In the new era, Henry Kissinger might maneuver to replace William Rogers as Secretary of State. But for all of his ambition and desire for the job, Harriman as National Security Adviser would never have done the same to Acheson, and indeed did just the opposite when the temptation presented itself. As Acheson concluded in his letter: “Your aid and steadfastness are one hundred percent reliable.”

During the month that followed, Acheson’s health and his spirits seemed to perk up a bit. He was able to get around more, to visit old haunts and see old friends. He seemed mellower somehow, as if he had reconciled himself to the disagreeable world he no longer had the power to change.

On a lovely, bright day in October of 1971, Acheson puttered about his garden at Harewood, readying it for winter. His old butler, Johnson, noticed that he seemed to be looking about, peering here and there, as if he were searching for something. Along about five, as the Indian-summer dusk settled over the Maryland countryside, Acheson went into his study. An hour later, Johnson found him there peacefully resting, dead of a stroke.

“Forty years in the Foreign Service is long enough,” Chip Bohlen wrote in his memoirs. In 1969, he retired from the State Department. He was sixty-four years old, “with enough energy left to make a little money.”

Bohlen was as usual strapped for funds, though not overly concerned about it. He still owned his cozy house on Dumbarton Street, full of books, Oriental rugs, and hunting scenes, “decorated in the Episcopal manner,” as his son, Charlie, dryly put it. A Filipino couple looked after him and Avis; after he got a job as a consultant to Morgan Bank there was even money for a summer house on Martha’s Vineyard.

Curiously, the product of St. Paul’s and Porcellian was in his old age a Humphrey Democrat. He had a genuine sense of social injustice, and he would even say about socialism, “maybe that is the road we ought to go down.” His children’s friends enjoyed visiting Dumbarton Street because, while the old diplomat was formidable, he was also curious and open to debate. He disdained unkempt student radicals, however. Watching the tumultuous 1968 Democratic Convention, he had little sympathy for the protesters. “He thought their intellectual arguments were shallow,” recalled his daughter Celestine. “And his instinctive reaction was why do they have to be so dirty and sloppy and foulmouthed?”

Though Bohlen was a dove, he was impatient with his children’s argument that the war was immoral. He would quote Montesquieu: “‘Twas not a crime, but a mistake.” He continued to believe that the U.S. had a moral obligation to oppose aggression. Nor had Bohlen softened on the Soviets. In July of 1968, listening to chic liberals at a Georgetown dinner party extol the promise of the Prague spring, Bohlen cut in, “The Soviets will crush it.” A month later, the tanks rolled.

If, in his last years, Bohlen deeply pondered his achievements and disappointments, he did not share his thoughts. To his children he seemed simply content with life. Bohlen did write his memoirs, but the exercise was torturous. He was both a poor writer and not terribly reflective; a New York Times reporter, Robert Phelps, had to rewrite the book, called Witness to History. Published in 1973, the memoir was pleasant and straightforward, but lacked the great sweep and rolling thunder of Acheson’s Present at the Creation, which won a Pulitzer Prize in 1970. The titles reflected their authors; if Bohlen was far less history’s shaper than Acheson, he was also more humble about it. (“If you had been as arrogant as Dean Acheson,” wrote a friend, “you would have called your book, ‘Sage Witness to History.’”)

Still very much in love with Avis after almost forty years of marriage, he looked forward to a long and happy retirement in her company, traveling and visiting old friends. He was spoiled, and a little helpless without her. Once, when visiting Celestine at Radcliffe, he lost his wallet. “You better call the credit card companies,” said Celestine. “We better call your mother,” said Bohlen.

Sickness cheated him. He had quit smoking in the mid-sixties when he woke up blind in one eye from an arterial spasm (he took to chewing golf tees). He regained his sight, but his gut rebelled, first from diverticulitis, then, fatally, from cancer of the colon.

The last years were hard. In growing discomfort as his innards slowly rotted, he was increasingly infirm. For his last year, he had to endure the indignity of a colostomy, a plastic bag attached to his intestines hanging outside his stomach. For Bohlen, who had borne much in life but who loved good food and gay evenings, the illness was as disappointing as it was painful. “He would rather have died quicker and cleaner,” recalled his son.

At the end, Bohlen even lost his love of argument. His old chum from St. Paul’s and Harvard J. Randolph Harrison recalled trying to cheer him at his bedside with friendly debate. For more than fifty years Harrison had been able to cheerfully provoke his old school and club mate by taking a staunchly conservative line. But now, in the winter of 1973, Bohlen was just too sick.

George Kennan had not seen his old friend for years. Intellectually, they had grown apart. “Chip had become an Achesonian,” Kennan recalled. In the late 1950s the two had argued “into the wee hours” over the Suez crisis during a weekend at Kennan’s farm, but the debate had been their last. “He was always sensitive to hurting my feelings,” Kennan recalled. “I think we just agreed not to argue.” Unable to discourse, the two lost their bond and grew distant.

In the summer of 1973, Kennan heard that Bohlen was dying. After so many years, so much shared experience, he felt he had to see him one last time. He took the train from Princeton and arrived at Dumbarton Avenue to find Bohlen, whose charm and handsomeness he had envied so, a pale, emaciated specter. Bohlen bravely greeted him, “When I get over this. . .”

“I could see from his eyes that he knew he was going to die,” recalled Kennan. “We avoided talking politics, and we really had nothing to say.” Kennan quietly bade his dear partner farewell and left his bedside in tears. A few months later, on January 1, 1974, Bohlen passed away in his sleep.

Trim and erect, Kennan was strangely ageless. His head bald and smooth as a marble bust, his eyes clear blue and slightly sad, he sat alone in his book-strewn study at the edge of a forest in Princeton, writing history. He was as ever “the guest of one’s own time and not a member of its household.” The 1970s, with spreading shopping malls, discos and condos, Big Macs and Burger Kings, made him long even more for the age of Tolstoy.

From his remote perch, he watched American foreign policy erratically swing between extremes, from Kissinger’s realpolitik to Carter’s human rights crusade to Reagan’s simplistic rhetoric of confrontation. Kennan yearned for those few years right after the war when a small band of able and selfless men controlled foreign policy relatively immune from the politicians. To the quintessentialy elitist Kennan, the spectacle of Congress blundering into the delicate arena of world affairs was abhorrent; equally discouraging was the gamesmanship of modern presidential advisers, leaking madly and trumping one another in a frenzy of self-promotion. Foreign policy, Kennan believed, had become political theater. By sacrificing realism to polemics, consistency to opportunism, America had forfeited its role as world leader. “For a country to be ruled this way,” declared Kennan in an interview with historian Ronald Steel in the fall of 1984, “disqualifies it from active participation in the world.”

Kennan was eighty years old in 1984, moody and disenchanted as ever, yet alert and penetrating. To see Russia once again caricatured by an American President as a voracious monster was, to him, a nightmare. The vision of the Soviets as an “Evil Empire” bent on destruction of the West was, he deeply regretted, the bastard child of his X-Article, always misperceived and long since disinherited, yet as resilient as a deep-rooted weed. “A great many people in an official position in this country don’t seem to know that Stalin is dead,” Kennan wearily remarked on more than one occasion. In his own view, the Soviets had become defensive and ossified, barely able to maintain their own empire, much less extend it. Certainly they were not about to invade Europe. Yet to Kennan’s deep foreboding, the U.S. seemed fixated on the military threat, caught in the “vast addiction” of the arms race. It was just this sort of paranoia and militarism that drew the Great Powers into World War I, Kennan wrote in a book published that fall, The Fateful Alliance.

As in 1914, the superpowers were once again steering blindly into harm’s way, Kennan wrote, “this time for a catastrophe from which there can be no recovery.” His pessimism at times was “almost total,” he confessed gloomily. “I’m afraid that the cards are lined up for a war, a dreadful and final war.”

In his morbid contemplations, he fastened on the greatest source of evil, not heedless politicians or clashing nationalism, but nuclear weapons themselves.

Ever since he had written his cri de coeur against the “Super bomb” in the fall of 1949, he had regarded nuclear weapons as the serpent in the garden. Though the Bomb might seem to offer ultimate security from attack, the mere existence of such lethal weapons is temptation too great in a world of dangerous passions. The Bomb is “a suicidal weapon,” he argued, “devoid of rational application in warfare.” By making triggers hair thin and warning times ever shorter, the arms race heightens jitters and the risk of terrible impulse. “The danger lies not in the possibility that someone else might have more missiles and warheads than we do, but in the very existence of these unconscionable quantities of highly poisonous explosives.”

For Kennan, nuclear weapons became a last great crusade. The old geopolitical analyst, having pondered for a half century on the forces that drive nations apart and send them to war, chose as his last field of concentration the one force that could doom mankind.

He did not engage in this grim exploration as a theoretical exercise. Rather, he abandoned the obscurity and safety of academe to become a public figure once again, a controversial spokesman for arms control. He helped launch a public campaign calling on the West to adopt a policy of “no first use.” Nuclear weapons will never be eliminated, he conceded, and some are necessary for deterrence. But the West should rely primarily on conventional forces; for NATO to threaten nuclear retaliation as its response to a conventional attack is to beckon annihilation. “If there is no first use of these weapons,” he argued, “there will never be any use of them.”

Kennan’s allies in this ultimate cause were not dreamy ban-the-bomb types but former paladins of the Cold War, principally Robert McNamara and McGeorge Bundy. His case was made not just on the pages of Foreign Affairs but on op-ed pages of papers across the country and before hot television lights in crowded press conferences. It provoked an immediate and sharp rebuttal by the Secretary of State, Alexander Haig, who warned that a policy of “no first use” was “tantamount to making Europe safe for conventional aggression.”

Through most of his career Kennan was a loner who seemed almost to prefer contrary and unpopular causes. His final one, like many of those before it, was not likely to prevail, at least in the chilly clime of the mid-1980s. Yet it ennobled the debate and forced policy makers to question assumptions. The “no first use” doctrine certainly cannot be dismissed, if for no other reason than history shows that Kennan’s warnings are ignored at risk.

It may seem curious to find Kennan, who had warned early and often against engagement in Vietnam, joining forces with Bundy and McNamara, a pair of former officials widely blamed for fulfilling his prophecy. But Kennan bore no grudge. “I never questioned either one about Vietnam,” he recalled. “I thought Bundy was a staff man who had his doubts about the war, and I sympathized with him. McNamara I respected for changing.”

In fact it is typical that Kennan was able to get along with men whose policies he had once deplored, without showing a trace of animus or even irony. Transcending his contrariness, as well as his utter helplessness in bureaucratic struggles, was his deep sweetness of nature. He never lost this gracious quality, not even in his relationship with Dean Acheson, his prickly nemesis of the postwar years.

“Even George Kennan writes praising my treatment of him,” Acheson told a friend in some amazement after Present at the Creation was published. “I think you dealt with me fairly and generously in your memoirs,” Kennan had written. “There is nothing there to diminish in any way the feelings of respect and affection for you with which I left our association in the Department 20 years ago and which even our differences over Germany and Europe failed to dim.”

At the very least, one would expect relations to be cool between Kennan and Paul Nitze, the man who displaced him as Acheson’s chief planner. They could hardly have presented a greater contrast: Nitze the smooth insider versus Kennan the insecure outsider, Nitze the militarist versus Kennan the diplomacist, Nitze the doer versus Kennan the thinker. Yet the two remained through all the years the best of friends. Indeed, the toast that most deeply touched Kennan at his eightieth birthday was delivered by Nitze. Raising his glass to his gentle old foe, Nitze in his soft patrician voice praised Kennan as a “teacher and an example for close to forty years.” Smiling slightly, Nitze remarked that “George has, no doubt, often doubted the aptness of his pupil. But the warmth of his and Annelise’s friendship for Phyllis and me has never faltered.” Rising to respond, Kennan graciously toasted Nitze as an example to him as well. Wrestling with self-doubt even as he entered his ninth decade, Kennan ruefully second-guessed his own long absence from government by praising Nitze’s willingness to serve through each new Administration, regardless of disagreements over policy. “It may be best to soldier on,” sighed Kennan, “and to do what one can to make the things you believe in come out right.”

Friendship, no matter how enduring, could not paper over deep splits that cracked apart the foreign policy Establishment in the 1970s.

For two decades, the Establishment had held sway by sitting squarely astride the middle ground of “informed” public opinion. But by the seventies, the center no longer held; Vietnam had shattered the post-World War II consensus. Power swung to the extremes. The right was just as noisy as ever, but the left began to shout too. The sound heard abroad by U.S. allies was dissonance.

The old Establishment was not immune to the tugging and pulling. The split that had emerged between “soft” and “hard” wings in the Democratic Advisory Council back in the fifties, when the Achesonians had faced off against the Stevensonians, became more open and hostile. Vietnam forced nearly everyone, even the old guard, to choose sides between “hawk” and “dove.” In the fifties, though they differed over method, the “hard” and “soft” camps did not quarrel over the fundamental assumption that the U.S. had a dominant world role to play. But now liberals had become quasi isolationists; they argued that the U.S. was badly overextended and had to pull back, that Communism was not monolithic and that its threat had been grossly overstated.

Vietnam had pushed Averell Harriman leftwards, made him reject many of the Cold War verities that he once believed and indeed helped propagate. He was not in full retreat; he never stopped believing in an active global role for the U.S. But by the 1970s he had come to accept the limits of intervention, and he was determined as ever to reduce tensions with the Soviets by negotiations and diplomacy.

He was delighted when his partner at the Paris Peace Talks, Cyrus Vance, was made Secretary of State by Jimmy Carter. Vance had just about the right world view for Harriman, a desire to deal with the Russians, a predilection for diplomacy over force, an appreciation for nuance and subtlety in foreign affairs. He had the right personal qualities: he was honorable, decent, and discreet. He was, as well, the right sort, a product of the inner sanctums of Yale and Wall Street. Harriman, of course, would be the first to deny that such things mattered any more, and in truth he was not a snob; but he could hardly avoid feeling a bond to someone so much of his world.

When Jimmy Carter won election in 1976 by running a populist campaign against insider Washington, his chief aide, Hamilton Jordan, vowed, “If, after the inauguration, you find a Cy Vance as Secretary of State and Zbigniew Brzezinski as head of National Security, then I would say we failed. And I’d quit.”

The fact that Carter hired both men—and that Jordan did not quit—was held out at the time as evidence that the Eastern Establishment was alive, well, and still indispensable. But in fact the selection of Brzezinski and Vance showed precisely the opposite. Brzezinski and Vance were only superficially similar. True, they were both members of the Trilateral Commission, David Rockefeller’s elite international meeting group, and regulars at the Council on Foreign Relations. But in fact, they couldn’t have been more different, and their differences perfectly embodied how much the machinery of foreign policy making had evolved from the days of Lovett and Acheson, though not necessarily for the better.

To Brzezinski, Vance represented the “once dominant WASP elite” that was in its dotage. In his memoirs, Brzezinski scorned Vance’s “gentlemanly approach to the world” and found it quaint that Vance was reluctant to authorize spying on foreign embassies. “Like Secretary Henry Stimson earlier, he seemed to feel that one should not read other people’s mail,” Brzezinski marveled. “All in all, in temperament and timing, Vance was no longer dominant either in the world or in America.”

Brzezinski himself was not of the old Establishment (“it certainly was not easy for me to relate to it”) but an exemplar of the new “Professional Elite,” as I. M. Destler, Leslie Gelb, and Anthony Lake describe it in Our Own Worst Enemy: The Unmaking of American Foreign Policy. Like Kissinger, indeed like many of the new foreign policy activists who had arisen to challenge the Establishment in the sixties, he was both an academic and foreign born. Power did not come to him by birth or place; he had to grasp for it. His expertise and force derived not from experience in business or government—or from anything he had accomplished—but from ideas. He was a polemicist; his stock-in-trade was the trenchant op-ed page piece, the well-considered quote. Politicians did not offend him; indeed he had actively sought out and cultivated Carter when the Georgia peanut farmer was still “Jimmy Who?” When Carter formed his government in January of 1977, Brzezinski maneuvered to insure that the real insider, the President’s true counsel, was not the Secretary of State but the National Security Adviser; not Vance but himself.

Harriman, with his well-honed instincts for bureaucratic intrigue, saw immediately what Brzezinski was up to. “Ave was not too fond of Zbig to begin with,” recalled William Sullivan, Harriman’s protégé during the Laos negotations who had risen through the State Department ranks to become ambassador to Iran, “and he grew less fond when he realized what a dangerous type he was.” Harriman remembered that when he was National Security Adviser to Truman he had sought to protect the Secretary of State. “If I had gotten in the way of the relationship between the President and the Secretary of State,” he told friends, “I would have been fired, and properly so.”

Harriman was able to observe Brzezinski close hand because the National Security Adviser was living in his home. The Harrimans, whose home had become a glorified boardinghouse for visiting dignitaries and out-of-town statesmen, had graciously offered to put up Brzezinski for a few weeks in January until he could move his family down from New York. The weeks turned into months, and Harriman found his houseguest increasingly arrogant and self-serving.

Harriman was equally disturbed that Vance let himself be trumped by Brzezinski. Privately, out at his estate in Middleburg, Virginia, where the Vances often came for the weekend, Harriman urged his old negotiating partner to stand up to his White House rival. Vance listened, but at first he refused to believe that Brzezinski’s motives and actions were as base as everyone kept saying. Not until the Iran hostage crisis, when Vance discovered that Brzezinski had his own secret channel of communication with Iran, and Brzezinski just flat out lied and denied it to the President, did Vance fully appreciate with whom he was dealing. When Carter ignored Vance’s warnings and took Brzezinski’s advice to launch the hostage rescue mission that failed so ignominiously in the Iranian desert, Vance resigned from office, defeated and discouraged.

Harriman objected to Brzezinski’s ideas as well as his methods. He felt the National Security Adviser was a belligerent hard liner toward the Soviets, and he frankly blamed his ethnic origins. “He thought Zbig was basically a Pole who had never accepted the American ethos,” recalled Sullivan. “He believed Zbig was perfectly willing to get the U.S. into a confrontation with Russia for the sake of Poland.”

All along, Harriman had never stopped working for better relations between the U.S. and U.S.S.R. Though no longer in government, he continued to serve as an occasional emissary to the Kremlin for every President from Nixon to Reagan. He visited Moscow on diplomatic missions no less than a half dozen times after his eightieth birthday: in 1971, 1974, 1975, 1976, 1978, and 1983.

At the time of his last trip he was ninety-one years old. The phenomenal robustness that had sustained him through those endless plane flights to remote capitals had finally begun to fade (though doctors had to order him to quit skiing when he turned eighty). He was quite deaf, his vision was blurred, and he was becoming slightly senile. His mental toughness was unbowed, however; to younger men, he could still be the Crocodile, snapping off their foolish answers with a curt dismissal. He was still a Washington presence, in part because of the exertions of his politically active wife. In 1971, a year after Marie’s death, he had married Pamela Churchill Hayward, the beautiful young woman he had fallen in love with in wartime London thirty years before.

Like Kennan, Harriman was disconsolate when Reagan began fulminating against the “Evil Empire.” He felt it was his duty to assure the Soviets that not all Americans had succumbed to such foolish hyperbole. Besides, he had never met the new Soviet leader, Yuri Andropov. He told friends that he wanted to take his measure.

One last time, Harriman accepted his standing invitation to visit the Soviet Union. Well rested from a night in Armand Hammer’s suite at the International Hotel, he was completely alert as he sat down one October morning in 1983 with Andropov at the familiar long table in the Central Committee Headquarters in Moscow. He had been there so many times that even the Soviet interpreter, Victor Sukhoderev, knew him. From experience with Harriman’s deafness, Sukhoderev knew how to pitch his translation of Andropov’s answers so the old diplomat could hear.

The Soviet leader was gracious. “We remember well that you stood with us when the Germans were firing at the gates of Moscow,” Andropov said in greeting him. “You understand how important it is that our two countries work together for peace.”

They discussed the threat of war, the risk of miscalculation, the need for arms control. They agreed that both countries had to work to maintain normal relations, whatever the politics of the moment. When the conversation was over, the aging capitalist firmly shook the old Communist’s hand and, with a gruff farewell, ended his years of personal diplomacy to the enigmatic nation he had first visited eighty-four years earlier as a boy.

That winter, Harriman was rolled by a wave on the Caribbean island of Barbados and broke his right leg. It is perhaps typical that Harriman was gamboling in the surf at the age of ninety-two, but the injury was nonetheless serious. His wife worried after the accident that “Averell was just tuning out.” For the first time anyone could remember, he had no interest in the news, or current affairs, or even Russia. All he cared about was getting well. He brought to that task the same single-minded intensity he brought to other causes he had cared about. “Aren’t you worried about Reagan?” the doctors would ask him. “I don’t give a damn!” he would growl. “When am I going to walk again?”

His leg mended; he began worrying about Reagan and the Russians once more. “What do you think about U.S.-Soviet relations?” he would demand of visitors without any prefatory small talk. The Soviets did not forget him; on the fortieth anniversary of V-E Day in 1985, amidst speeches denouncing the U.S. as a warmonger, the News Agency Tass announced that Harriman had been awarded the Order of the Patriotic War, First Degree, for “his great personal commitment to the improvement and strengthening of Soviet-American cooperation.”

Death could not be put off forever, but Harriman was not one to give in easily, even to mortality. For nearly a century he had bargained with formidable adversaries, from the Rector to Soviet dictators. As he approached the end of his time, he seemed locked in a prolonged negotiation with his Maker, seeking, no doubt, an honorable peace. In July of 1986, Harriman returned to Arden, where he died at the age of ninety-four.

For John McCloy, the last years saw a slow ebbing of his peculiar mix of public and private power. The decline had less to do with McCloy, who remained fit and alert well into his eighties, than with the world changing around him.

When he resigned as chairman of the Chase in 1960 to return to the law, he did not leave Big Oil behind. He merely went from financing the petroleum industry’s Middle Eastern empire to protecting it from the Justice Department.

Shortly after McCloy became the senior partner at Milbank, Tweed (renamed Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy), he was made general counsel to all the Seven Sisters. “My job was to keep them out of jail,” he bluntly put it. As usual, McCloy seamlessly blended public and private concerns. After his chilly summit with Khrushchev in 1961, Kennedy summoned McCloy to the White House to discuss with him the threat of Soviet incursions in the Middle East. McCloy took the opportunity to plead for his clients on another matter altogether. The Arab oil-producing states were restless, he told the President. They had joined together to create a bargaining agent called OPEC. The organization was weak and divided for now, but it could become a real force to extract higher prices from the oil companies. That would hurt not just oil company profits, McCloy argued, but U.S. national security, which depended on a steady supply of cheap oil. To deal with the threat of OPEC, the oil companies would need to band together themselves. And to do that, they would need assurances from the Administration that the Justice Department would not sue them for breaking the antitrust laws.

“Then and there,” McCloy recalled, JFK telephoned his brother, the Attorney General. McCloy was assured that if a crisis arose, and the oil companies needed to act as one, they would get a sympathetic hearing from the Department of Justice.

McCloy made sure his lines stayed open to the Justice Department. “I made it a point to call on each succeeding attorney general,” McCloy recalled, “just for the idea of keeping the thing fresh in his mind, because any moment I was afraid we would have to do something.”

The Arab countries had long been resentful of Western oil companies, which dictated prices and artificially held them low. But the Arab leaders were fundamentally conservative and could be reasoned with, stroked and cajoled by persuasive Westerners like John McCloy.

Not so Muammar Qaddafi. The hotheaded young revolutionary who had seized control of Libya in the late sixties did not hesitate to unilaterally jerk up oil prices. He got away with it because several of the independent oil companies had no other supplier. Qaddafi’s boldness set off a chain reaction: all through the Middle East oil-producing states suddenly became profit hungry and began raising the price of oil.

The moment McCloy had warned about had arrived. In January of 1971, representatives of the Seven Sisters—plus nineteen other oil companies that had retained McCloy’s services—met in the old statesman’s corner office on the forty-sixth floor of One Chase Manhattan Plaza. Outside in the anteroom, beneath the photographs inscribed to McCloy by every President since FDR, representatives of the State and Justice Departments sat reviewing drafts of the proposed cartel.

McCloy strongly urged the oil companies, many of whom had divergent interests, to band together to defy OPEC. He was blunt: “You either hang together, or hang separately.”

McCloy succeeded in both hammering out a deal among the oil companies to “hang together” in bargaining with OPEC and at persuading the Attorney General John Mitchell not to sue them. It was, as historian Alan Brinkley has written, “a virtuoso display of private and public power exercised simultaneously.”

But it did not last. The Arab countries had tasted independence and profits, and they wanted more—they wanted at least part ownership (“participation”) in the oil concessions on their soil. A looming global oil shortage gave them leverage.

The 1973 Arab-Israeli war wrecked any power the oil companies had over OPEC. McCloy had seen the conflict coming, and anxiously warned the Administration not to ship arms to Israel for fear of provoking the Arabs. As he had done thirty years earlier on the questions of bombing Auschwitz and internment of Japanese-Americans, McCloy placed pragmatic considerations ahead of moral ones. “I kept jumping on him [National Security Adviser Kissinger] to say that it was an imperative of statesmanship to get the Middle East settled; that the Administration must not think in terms of the next New York election,” McCloy recalled. Promising his clients that he would get a letter to Nixon, McCloy wrote to White House Chief of Staff Alexander Haig in October by special messenger warning against increased aid to Israel, arguing that the Soviets and Europeans would move into the Middle East if the U.S. was cut out. “Much more than our commercial interest in the area is now at hazard,” McCloy beseeched the President. “The real stakes are both our economy and our security.” The White House, in the throes of Watergate, did not even answer the letter for three days, and the arms shipments were made.

The Arabs did impose an oil embargo. The price of oil quadrupled in seven months. In the U.S., lines of cars circled gas stations all over the country, and the oil companies were widely, if unfairly, accused of conspiring with the Arabs to artificially create a shortage—especially when they announced large profits at the height of the energy crisis.

After years of comfortably aligning the national interest with his clients’ interests, McCloy was appalled to see the oil companies so vilified. “It seems that it is only in the United States that an almost masochistic attack on the position of its own oil companies persists,” he grumbled before a congressional investigation.

Authority itself seemed besieged in the mid-seventies. The President had been driven from office, foreign bribe scandals were breaking daily, talk of slush funds, and scandal in boardrooms as well as the White House reverberated throughout Washington. Under congressional pressure, the Justice Department revoked its promise to McCloy not to sue the oil companies for antitrust violations.

McCloy himself was not tarred. He managed to float above the furor, his integrity intact. When Gulf Oil was charged with making illegal contributions to Nixon, the directors turned to McCloy to conduct a public investigation. McCloy’s report, fingering the oil company’s highest officials for blame, was unblinking and impartial.

Yet McCloy’s well-ordered world was in tatters. In Washington, Watergate and Vietnam had given a bad name to the private exercise of power. No longer could a small group of like-minded men sit down and quietly decide for the country; now, it seemed to McCloy, TV cameras and congressional committees followed decision makers everywhere, and thus froze them.

The broader rumblings of revolution around the world left McCloy perplexed. He favored Third World development, but had little feel for the nascent forces of nationalism. He was only slightly less obvious than his friends Acheson, Kennan, and Lovett, Europeanists all. They had never shown an interest in the Third World, and they were not about to develop one. “Point Four,” Truman’s famous call for aid to underdeveloped nations in his 1949 inaugural address, had been the creation of Truman’s political advisers, not the State Department. Indeed, when a draft was shown to Lovett and Nitze, they “were neither enthusiastic nor impressed with its utility,” dryly remarked Dean Acheson. Nor, for that matter, was Acheson, who regarded Point Four as political rhetoric, not a mandate to be carried out. Kennan was so disdainful of the underdeveloped world that he invariably used quotation marks around “Third World,” as if he refused to accept its legitimacy.

In later years the Establishment’s old guard (with the significant exception of Harriman) usually backed foreign regimes, no matter how repressive, against local insurgents. Horrifying their liberal friends, both Acheson and Kennan had little sympathy with black Africa, speaking out in favor of the white governments in Rhodesia and South Africa.

McCloy’s own cause was the Shah of Iran. The two had dealt with each other for years; McCloy’s law firm represented the Pahlevi family. To him, the Shah was a moderating force in OPEC, a man who could be reasoned with. When the U.S. at first refused to give the exiled Shah permission to enter the U.S. for medical treatment in 1979, McCloy was outraged. Along with David Rockefeller, his successor at Chase, and Kissinger, McCloy vigorously lobbied the Carter Administration to let the Shah in. “John is a very prolific letter writer,” dryly remarked Secretary of State Vance. “The morning mail often contained something from him about the Shah.”

Though Vance insists that the Old Boy lobbying did not affect him, the fatally ill deposed emperor was allowed to enter a U.S. hospital. Angry Iranian radicals promptly took over the U.S. Embassy in Iran, demanding that the U.S. expel the Shah. For the next 444 days, they held hostage fifty-two Americans.

McCloy was stunned, baffled, and chagrined. When a scruffy band of Islamic fundamentalists waving American-made rifles and shouting, “Death to America! Death to the Great Satan!” could paralyze the Administration and shame the U.S., it was increasingly apparent to him that his own day was over.

He had served dutifully as a Wise Man to every new Administration. Kissinger, for instance, recalls that when he returned from a round of arms talks in Geneva in 1975, the first person he called for advice was McCloy. The old arms controller came right over, missing his eightieth birthday party and never even mentioning it.

Yet McCloy could feel his influence waning in Washington. President Carter was an outsider who knew little of the old foreign policy Establishment and owed it nothing. When he invited McCloy to discuss disarmament, he herded him into the East Room along with fifty other people, like so many tourists. “It was a cattle show,” McCloy sighed to Time columnist Hugh Sidey.

The Reagan Administration was more appreciative. Reagan put McCloy on his transition team; for his ninetieth birthday, McCloy was honored in a ceremony in the Rose Garden at the White House. The President, Vice-President, Secretary of State, and chairman of the Federal Reserve were among those present. “John McCloy’s selfless heart has made a difference, an enduring difference, in the lives of millions,” President Reagan declared. “Compared to me, what a spring chicken you are,” said McCloy to Reagan.

The next night he was feted at the Council on Foreign Relations at a black-tie dinner attended by old Wall Street barons and various pillars of the Western Alliance, including former West German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt. David Rockefeller pronounced McCloy “the first Citizen of the Council on Foreign Relations,” and presented him with a plaque to hang under his portrait—already prominently displayed on the council’s dark paneled walls of the second-floor meeting room—that read: “Statesman, Patriot, Friend.”

In an evening of encomiums, the praise at once most laudatory and humble came from Henry Kissinger: “John McCloy, I believe, heard the footsteps of God as he went through history,” said Kissinger, quoting Bismarck, “and those of us who were not humble enough or whose ears were not sharp enough had the privilege of knowing that if we followed in his footsteps we were in the path of doing God’s work.”

McCloy listened, slightly embarrassed, his face downward, head slightly cocked, eyes glancing upward like a young boy anxious to please. His humility was characteristically sincere. “I know that many of the things said tonight were exaggerated,” he said, “but they made me feel warm. My record has its pluses and minuses. I only hope that it has been credible, that people can say of me: he did his damnedest, the angels can do no more.”

As he approached his tenth decade, McCloy, for years a most private man, began to compile his memoirs. He went about it in a characteristically informal way, dropping in on old friends and chuckling over familiar anecdotes while a tape recorder ran.

Inevitably, he found himself sitting with Bob Lovett out at Pleasance, Lovett’s small estate in Locust Valley, swapping tales and reliving their days as the “Heavenly Twins” in Colonel Stimson’s War Department. Lovett had missed McCloy’s ninetieth birthday party. “My doctor won’t even let me out on parole,” he apologized to his old friend. He went on that “in the past sixty years of our friendship, one very special time stands out for me—our service together under Colonel Stimson in Washington. Strangely enough, that very unhappy period in the world stands out as one of the most exciting and happiest of my life.” Now, as the two friends rambled on contentedly for almost six hours on a summer’s day in 1984, they amused each other with various moments high and low, like Stimson’s inability to work his squawk box and the time they conspired to spike Henry Morgenthau’s plan to turn postwar Germany into a rural pasture. The conversation was light; neither man was the sort to go in for profound utterances about their lasting contributions to Western society. Yet there was running through the conversation an undercurrent of discouragement, sadness almost, about the way foreign affairs had been conducted in more modern times. Though neither man would ever be caught boasting unduly about his own achievements, when they measured the men who came after, they could not help but find most of them wanting. “I like to believe,” McCloy wrote Lovett afterward, “that we had no axes to grind except to serve the country as well as we could.”

Shy Bob Lovett, the most discreet and self-effacing of the Wise Men, had vanished from the public stage altogether by the 1970s. His “glass insides” were mostly shattered; part of his stomach and various internal organs had been removed; he was stricken by heart attacks and cancer both. Yet, like McCloy and Harriman and Kennan, he was indomitable, still going into his office on Wall Street at the age of eighty-nine.

His mind stayed lucid long after his battered frame had worn out. Greeting a pair of visitors whose total years fell well short of his, he put them at ease with the same grace and gentle charm that had melted congressional committee chairmen in the 1940s. After offering tea from a silver service, he sat back, rather uncomfortably, on an overstuffed chintz couch. (Occasionally, he would stagger to his feet and limp around on a walker; his buttocks, he matter-of-factly explained, had been replaced by steel plates, and he was unable to sit for long.) On the walls hung cheerful landscape paintings, including one by Alice Acheson. Behind him, through French doors, Adèle’s garden flourished magnificently in the spring sunlight (he claimed not to be impressed with his dear wife’s labors, insisting in his quirky way that he preferred darkened movie theaters).

He did not conceal his scorn for the current state of affairs. “I have a gut feeling that recent Secretaries of State are uncompromisingly mediocre,” he allowed. In his day, Secretaries “were mostly damn good lawyers.” Cy Vance, he added ruefully, was “too much of a lawyer—too cautious and compromising.” He was displeased to see Congress assert itself in foreign affairs. “We now have 535 Secretaries of State,” he said. “Everyone sounds out.” Brzezinski, whom he referred to sardonically as “Zbiggy,” drew his deepest scorn. “We shouldn’t have a National Security Adviser like that who’s not really an American,” he protested, echoing Harriman’s blunt nativism. “I can’t imagine anyone negotiating with the Russians with his loathing and suspicion.”

As Lovett passed his ninetieth birthday, he slowly faded and withered. He shrank to 89 pounds and complained with his undimmed humor that “my bones click.” In January of 1986, Adèle, his companion of nearly seventy years, passed away. Each morning for the next three months, Lovett rose, painstakingly dressed himself in suit and necktie, and graciously answered the nearly three hundred letters of condolence that poured in. A few days after he had written his last remembrance of Adèle, he readied himself to join her.

On May 7, 1986, a half century after he first protested that he was not physically up to the rigors of government service, Robert Lovett died. In the bright light of a spring day, he was laid to rest in a laurel grove not far from his home, beside his mother, father, and wife. An editorial in the Washington Post recalled his service to the nation: “There is much by which to remember him and the people with whom he worked in those crucial years, but the greatest of their memorials is the long and durable peace among the countries that fought in the two world wars.”

Lovett’s disenchantment with the new “Professional Elite” that supplanted his own Establishment could be dismissed as the maunderings of an elderly man whose time has passed. For years, after all, it was Lovett’s Establishment that was blamed by revisionist historians for the Cold War, the arms race, Vietnam, and whatever else was dangerous and wrong about the postwar world. But as scholars and historians begin to examine the new foreign policy elite—polemical, leaky, self-interested, faction-ridden—they have begun to feel quite nostalgic about the old one.

The pendulum has swung partway back; the policies of Acheson and Lovett may have been flawed, but they were at least consistent; the men who made them may have been narrow-sighted, but they were good deal more selfless and disciplined than their modern counterparts. “There was a foreign policy consensus back then, and its disintegration during Vietnam is one of the great disasters of our history,” states Kissinger. “You need an Establishment. Society needs it. You can’t have all these constant assaults on national policy so that every time you change Presidents you end up changing direction.”

By the mid-1980s, the tradition of a nonpartisan foreign policy elite, carrying on steadfastly through political whim and turmoil, had nearly vanished. The long line that began in Teddy Roosevelt’s day at the turn of the century, that flourished in the postwar era and foundered so tragically during the Vietnam conflict, had very nearly come to an end. It had thrived for more than half a century, through Elihu Root and Colonel Stimson, through Acheson and Harriman, Lovett and McCloy, Bohlen and Kennan, and on down to the ill-starred brothers Bundy. But in the cynical seventies, its fading remnants, honorable men like Cyrus Vance, had been overwhelmed by a raw new order.

There was in 1985 but one true survivor, a single legacy from a lost age. Paul Nitze, Dean Acheson’s brilliant protégé, never realized his ambition to become a Secretary of State or of Defense, perhaps because of a steely personality some found too reminiscent of his mentor’s. Yet Nitze stayed on in public service through the eighties, pursuing power without at the same time sacrificing his integrity.

As an adviser and negotiator in the arcane but essential realm of arms control, Nitze became a master bureaucratic player, but so sportsmanlike (or at least subtle) that he seemed a curious anachronism to younger, more brutally cutthroat colleagues. Like Kennan, he hardly seemed to age. Perpetually tan, his white hair thick and wavy, he was in astonishing physical condition. At one luncheon party out at his Maryland farm, he startled his guests by dropping to the floor and in his sixth decade, huffing out a few one-armed push-ups.

Throughout most of his career, Nitze has pushed the U.S. to build more and bigger defenses against the Soviets. Yet he remained willing to cut a deal with the Kremlin if it would truly enhance nuclear stability. Nitze’s pragmatism has puzzled ideologues on both sides. Doves such as Jimmy Carter’s arms control adviser, Paul Warnke, scorned him as a hawk, while Richard Perle, Reagan’s hawkish Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Policy, dismissed him as “an inveterate problem solver.” Perle used the term pejoratively, to mean someone who solved problems for solution’s sake, even if the problem was better left unsolved. But the description accurately captures Nitze: he is an actor in the Achesonian tradition; he solves problems, regardless of political consequences.

Rarely was the triumph of ideology over pragmatism, of political posturing over serious statesmanship, so vividly demonstrated as during the weeks preceding the summit meeting between Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in November of 1985. While Reagan’s aides squabbled with each other, leaking documents and nearly paralyzing White House decision making, Nitze quietly kept searching for a formula that the Soviets and Ronald Reagan could accept. Against the backdrop of incessant propagandizing and infighting, Nitze’s selfless pursuit of real diplomacy seemed noble, if almost forlorn.

It is easy, of course, to put too much of a rosy glow on the postwar heyday of the old foreign policy Establishment. It was not always the “Periclean age” that McCloy imagined it to be. The bipartisan consensus collapsed over China and Korea, with unfortunate long-term effects on U.S. foreign policy. Acheson’s battles with Congress were epic and destructive. To win congressional support, Truman’s men consistently oversimplified and overstated the truth, and in so doing made anti-Communism dangerously rigid and U.S. commitments overly sweeping. With their penchant for action, Acheson and his cohorts sometimes failed to think first; their one visionary, George Kennan, was ignored after he came to be perceived as too soft and indecisive.

It can also be said, though perhaps with less justification, that they bore part of the responsibility for creating a world divided between East and West, overarmed and perpetually hovering at the brink. In theory, at least, the Grand Alliance of America, Britain, and the Soviet Union that won World War II might have held together to build an era of peaceful coexistence rather than Cold War. As tough and pragmatic men, Acheson, Harriman, and their cohorts were among the first to perceive—correctly—that Stalin was anything but a trustworthy ally. Even so, they would have been quite taken aback if they had realized in 1945 that for the next forty years—and perhaps for decades to come—the world would lurch from one crisis to another, driven on by a hair-trigger nuclear arms race. By overselling their cause and becoming fixated by some of their own rhetoric, they were doomed to watch as men less comfortable with subtleties and nuances shattered their vision of a stern yet stable modus vivendi between the U.S. and U.S.S.R.

All in all, it can be argued that by failing to anticipate the consequences of their words and actions, the men of the Establishment sowed the seeds of both the Vietnam tragedy and, ultimately, their own undoing.

Nonetheless, their victories were great. They did quite literally restore order from chaos, and, as Kissinger put it, “save the possibilities of freedom.” They forced a reticent nation to face up to its global obligation, to act as magnanimous conqueror and rebuild friend and foe alike after World War II. They created an alliance that has securely preserved the West from aggression for onward of forty years. Compared to all earlier empires, the Pax Americana was extraordinarily generous and idealistic, indeed, sometimes overly so.

The leading role played by the U.S. after World War II was not inevitable. Had Congress dictated events, the U.S. might have turned inward to pursue isolationist normalcy and, in Harriman’s phrase, “go to the movies and drink Cokes.” In the wild mood swings between indifference to the world and anti-Communist paranoia that were to buffet America in the postwar years, the making of foreign policy required sure and steady hands.

It is difficult to overstate the enormity of the task that faced the small group of men who set out to salvage Europe and bond the West against the Soviet threat that did, in fact, emerge from the rubble of World War II. Indeed, from the perspective of four decades, the challenge seems so daunting that one wonders: Where did such discreet and anonymous men find such power and will?

The men most responsible for America’s world role are, forty years later, half hidden in history’s shadows. Even their collective identity is in eclipse. They were by and large private men, uncomfortable with celebrity and rarely in search of it. “There was a sense of selflessness, of not playing to the galleries,” says Bill Bundy. They relished power, to be sure—Acheson once described his leaving office as akin to the end of a love affair. Yet they did not crave power merely to possess it.

Curiously, the small group of amateurs who revolved in and out of the State Department in the 1940s managed to get far more accomplished than the legions of full-time professionals who now inhabit the downtown think tanks and office warrens of Foggy Bottom, Capitol Hill, and the West Wing. Perhaps that is because the older generation was primarily concerned with serving their President and country, while the newer seems inordinately preoccupied with serving themselves. “My generation doesn’t produce people in the selfless tradition of a McCloy,” frankly admits Kissinger. “We’re too nervous and ambitious.” McCloy is almost bitter about the unwillingness of his successors on Wall Street to serve their country. Asked to name the next generation of lawyers and bankers wise in international affairs who might be called on to come to Washington, McCloy did not even pause to think. “You won’t find one,” he said. “Those lawyers don’t exist anymore. They’re all too busy making money.”

McCloy’s generation, it is true, did not have to worry much about material concerns. In an age of upper-class privilege, being “strapped” meant having to let go of the maid, or scale down a daughter’s debutante ball. To be sure, all but Harriman and Lovett fretted from time to time about their finances, but a glimpse at the life-style of the poorest of them evokes little sympathy: George Kennan, after all, could afford a country house, albeit a ramshackle one, and to send his children to private schools (his son, inevitably, went to Groton).

The truth is that these men were not bound by mortal coils. They did not have to worry too much about the daily chore of child care, or about their wives’ careers, or about paying the mortgage. They were relatively free to pursue what they really cared about: service to the country. In contrast to the careerists who now populate the official bureaucracy, or the grasping opportunists who value a sub-Cabinet post primarily as a springboard to a lucrative job with a government contractor, the amateurs of the old postwar Establishment actually seemed to enjoy their work. Public service was for them a demanding mistress, but a passionate one. Indeed, it seems to have been a sustaining life-force. In 1986, the year Harriman and Lovett died in their nineties, Kennan turned eighty-two and McCloy ninety-one.

These men owed no one. Free of political patrons, they served only the President. Even then, their loyalty was often more to the office than the man. They could afford the frankness born of intimacy; government in their time was virtually a club.

They did not need to grope for a sense of values. Though they mocked the Rector’s pieties, they nonetheless lived by his ethics. Virtues that now seem almost quaint, such as placing loyalty over ambition, were to them commandments.

The leaders of the old Establishment were self-confident enough to be selfless. Not always personally secure—Kennan, certainly, was exceedingly fragile—but self-assured in a broader sense. Products of institutions that preached service to country, they came of age at a time when it was possible to believe sincerely that America had a duty to serve the world. They came to power during a time “when Washington was at its best,” says George Ball, “and absorbed that yeasty atmosphere. It was an era when we weren’t taking a parsimonious view, worrying about balancing the budget, but about how the hell we were going to save the world.”

Acheson and Harriman, Lovett and McCloy, Bohlen and Kennan: they saw themselves, throughout their lives, not as public figures but as public servants. They rarely had to wonder about their place in society; they did not have to read the newspapers to know where they stood. Freed from the distraction of self, they were strangely liberated and empowered. They could bring their extraordinary energy, tempered by long exposure to the wider world, to the immense postwar task of rebuilding and making secure the shattered West.

There are, no doubt, diplomats and officials these days who are as brilliant as Acheson, as dogged as Harriman or McCloy, and as competent as Bohlen. There may even be some as prescient as Kennan and as honorable as Lovett. But there certainly does not now exist, and may never again, a breed of statesmen with the same synergism, the talent to work together in a way that transcends their contribution as individuals. Their triumphs and failures may be surpassed, but as a dying Acheson said to Harriman, “never in such good company.”

For better or worse, they were positioned by the chance of history to have consequence far beyond their individual identities. Secure in their common outlook, empowered by the bonds of trust, they met the challenge of a demanding new age. In their sense of duty and shared wisdom, they found the force to shape the world.