In reality it is not possible to draw an exact line and say here one kind of fishing becomes another, just as it is not possible to draw an exact line in any part of life to separate it from another.

Summer fishing came in so many different forms, became so many different arts, that there must be a start to it, a beginning and a middle and an end just to be able to see it.

The start was where the river passed a smaller stream that entered the river by the Ninth Street bridge.

Though summer had come, always lying back hiding was the cold snap—a late killing frost that caught everybody off guard so often that it seemed people would come to expect it and not set their garden vegetables out. But they are always surprised by the frost, and have to wrap paper around the plants in small cones until the backyards of everybody in town seem to be full of buried elves with only their hats showing.

But the frost does more than kill plants. Something about it affects the fish, and where the stream comes into the river just after the frost and even during the frost the northern pike come to feed. It is perhaps that they think it is fall, or perhaps the cold makes small fish come there and the big ones follow.

And they are truly big—some of them like twenty-pound green sharks, filled with teeth and savagery.

Fishing for them was done one way and one way only—casting lures. Two lures worked the best, and everybody who came to work where the stream flows into the river used one or sometimes both of them. The best was a red-and-white daredevil—a spoon that is silver on one side with red and white stripes on the other and a single triple-hook at the bottom, or business end. The new ones didn’t seem to work very well until they were scuffed and scratched by teeth tearing at the paint on them. Most of us tried rubbing them on rocks or concrete to scuff them up a bit, but it didn’t work as well as having it done by teeth. The other lure was called a plug—a simple cylindrical piece of wood painted red in the front and white in the back with two small silver eyes and a “lip” made of stamped metal to pull the plug under when it was reeled in.

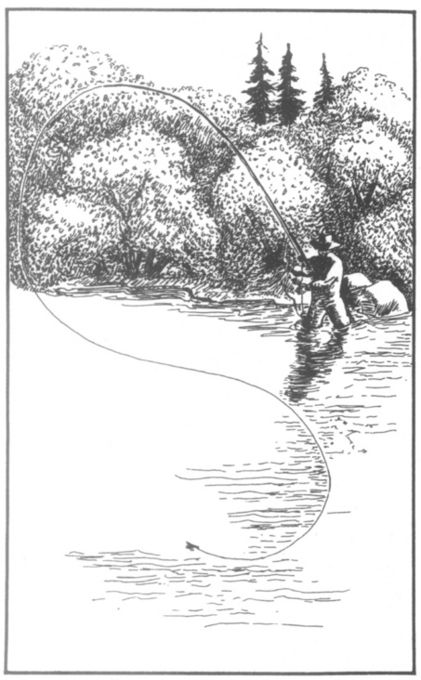

The rigs used then would not be considered usable by modern fishermen. This was all before glass or carbon rods and spinning reels or free-wheeling casting reels, and casting with them was a true art, a balance of coordination and luck. The line used was of a heavy braid—there were no monofilaments then either—rolled on a drum reel with thumb-busting side drive handles that had to spin with the drum when a cast was made.

Everything was in the thumb. The right thumb rested on the line drum, and the rod—a clunker made of spring steel and by modern standards about as flexible as casting with a tire iron—had to be whipped overhead and forward with great force at the same instant the thumb had to be lifted from the drum to allow the lure to pull the line out. But not all the way. If the thumb came up too much, the line would go too fast and cause a backlash—a tangle on the reel sometimes so hideous the line had to be cut from the drum with a pocketknife, hacked off, and replaced completely. But the thumb couldn’t be pressed too hard either, or the lure wouldn’t go anywhere.

And then, just as the lure entered the water the thumb had to act as a gentle brake and stop the line drum.

All to start just one cast.

And almost no casts produced a fish. It might take sixty or seventy casts to entice a northern to strike, and then it didn’t always pay off.

If the daredevil was used it had to be allowed to wobble down into the water no more than a foot, and then the rod had to be put in the left hand and the right hand had to grip the handles, and the line had to be reeled in as fast as the hand could move to make the spoon roll and flip and flash silver and red. Then, just before shore the daredevil had to be stopped, cold, for half a second in case there was what was called a “follow-up” to give a fish time to hit it just then.

The plug was slightly different. Because it was of wood it floated and so the cast had time to be developed correctly. The cast could be placed with more time, the plug allowed to drift into position, and then the reeling started at one’s leisure.

The lip on the front of the plug worked as a water scoop so that the faster the plug was reeled in the deeper it would dive, and the depth could be controlled that way. Some worked the tip back and forth to the right and left while reeling, but it didn’t seem to help, just as spitting or peeing on the lure—another trick used by some—also didn’t seem to help. Once somebody scrounged some blood from a butcher in a small bucket and dipped the lures in the blood, and that had some effect but made us stink for days of rotten blood and fish slime. It didn’t bother us, but in school there was a noticeable reaction.

Again, as with the daredevil, when the plug was close to shore it was stopped for half a moment to allow a possible follow-up strike, but really the cast was always everything. And though many—most—casts did not catch fish, each and every cast had to be made with art and skill and the hope, the prayer was always there that it would work; that this cast would work this time.

The problem was the cold. It was necessary to work the line in just the right place, reeling the braided line through the fingers to be able to “feel” when the first hit came, if it came. Braided line soaked up water, and this squeezed out on the finger, ran down the wrist, and dripped on the waist or legs—depending on where the reel was held.

Wet, cold hour after hour, each perfect cast followed by each perfect cast waiting for that moment, that split part of a moment when it comes.

The strike.

They are never the same. Daredevil strikes are different from plug strikes as cold-weather strikes are different from summer strikes, and every fish seemed to strike differently.

Northern pike are the barracuda of fresh water and when the mood is on them they will hit, tear at anything that moves. Mother loons keep their babies on their backs so the northerns won’t get them, and baby ducks get nailed constantly. Northerns eat anything and everything. In their guts we found bottlecaps, can openers, cigarette lighters, bits of metal, nails, wire, pieces of glass and once, complete, a pair of sunglasses that fit one of the boys perfectly.

But they’re picky. Not always, but sometimes. And they must be coerced, persuaded, into biting—begged, enticed.

A cast can be “dropped,” the lure allowed to settle, then reeled in fast, then allowed to settle again and once more reeled fast—to make it seem sick or wounded. It can be skittered across the surface, then suddenly stopped, skittered and stopped, teased and teased, looking, waiting for the moment:

The strike.

It always comes like lightning. Sometimes there is just the tiniest hint, a small grating of their teeth on the lure as they come in for the hit, but usually there is no warning. One second the reel is turning and the lure is coming in, and the next there is a slashing blow and the line stops, begins to sizzle out, cuts the finger, and the rod bends, snaps down, and in some cases, if it is a large fish and a steel rod, it stays bent in a curve.

It is impossible to judge size. Three pounds seems like six, six like twelve and over. One cold, clear morning a miracle came. A cast, one clean cast with a daredevil that slipped into the water like a knife, clean and in and halfway back, the reel spinning as fast as it would go; there was a small grating on the lure and then a tremendous slashing strike, a blow that nearly tore the rod away, and the line cut the water, sizzled off to the right so fast it left a wake.

A great green torpedo of a fish that tore the water into a froth, a fight that slashed back and forth until at last the fish was tired, until it nosed finally into the bank, where it could be dragged up onto the grass to lie, green and shining, the tail flapping, and a voice, a small voice notes the sadness of the fish and whispers in the mind and the words come out:

“Let it go.”

“Are you crazy?”

“Let it go—it’s too, too much fish to keep like this. Let it go.…”

“Nobody will believe it.”

“We saw it. That’s enough. Let him go.”

And so it is.

Somebody has a scale, a spring with a needle that slides, and the fish is weighed, and the lure is removed, and it is laid in the shallows. It wiggles twice, a left and right squirm, and it’s gone.

“It will learn,” somebody says. “It will never strike again.”

But he is wrong.

Four of us that day catch the same fish and release him, and each time he fights and each time he slides back into the river and disappears like a green ghost, and there are many other springs and thousands of other casts and hundreds of fish caught and eaten when it snaps cold where the stream comes into the river, but never the same again.

Never that same slamming surge of the first large strike.

Seventeen pounds.