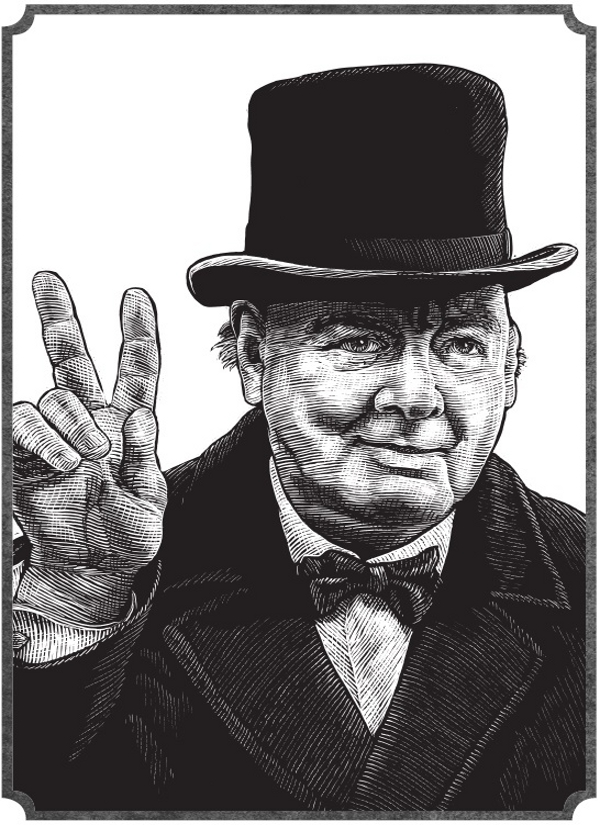

IT WAS LATE IN 1964 WHEN A LETTER ARRIVED AT A LONDON townhouse. The nine-year-old girl in Colombia, South America, who mailed the letter had done so without including a stamp or a complete address. Nevertheless, the postal service in Colombia had known just what to do. Workers there provided the missing stamp and sent the letter on its way. It arrived in England a few days later, where workers immediately sent it to 28 Hyde Park Gate in London. A secretary then opened the envelope, read the note inside, and handed it to a ninety-year-old gentleman sitting nearby. He smiled, grateful and amused. His name was Winston Churchill. The letter was addressed simply, “To the Greatest Man in the World.”

Winston Churchill was indeed the greatest man of his age. His life was astonishingly rich and productive. His gifts were measured in the gratitude of millions. His impact upon his world cannot be fully measured yet. It must be left to generations yet unborn.

He came into the world in 1874. There were men still living who had fought Napoleon. Abraham Lincoln had been president just nine years before. He grew up one of two sons of the American beauty Jennie Jerome and Lord Randolph Churchill, rising statesman and noted champion of Tory democracy.

His parents were typical of their day and left young Winston in the care of a nanny named Elizabeth Everest. This was fortunate. She gave him the love his parents were incapable of and led him gently to an understanding of the ways of God. She also embedded in him a sense of destiny that never left him.

He attended Sandhurst, the British military academy, and soon after found himself in the crossfire of battle in the Sudan, in Cuba, in India, and, finally, in the Boer War of South Africa, where he was captured and held as a prisoner of war. His escape made him world famous, and he parlayed this into a successful run for Parliament. His fortunes would rise and fall in British politics, but it was obvious to friends that he was being fashioned for a role beyond mere political infighter.

He served as first lord of the admiralty during World War I but resigned when his planned invasion of Turkey through the Dardanelles proved disastrous and resulted in the deaths of more than one hundred thousand men. He led soldiers in Belgium, returned to politics after the war, and then became an outcast in British society because of his impassioned warnings about the Nazi rise in Germany. England was weary of war, having lost a generation of young men in the trenches of World War I. Churchill seemed a shrill warmonger. He became one of the most hated men in Britain.

In the late 1930s, many of his predictions proved true. As the Nazis began marching through Europe, Churchill returned as first lord of the admiralty and then, when no amount of appeasement would make Hitler stand down, was summoned by the king to serve as prime minister. It was a terrible time in history, and many commentators predicted the end of the Western democracies. Churchill saw the threat but believed in his nation, his God, and his own destined purpose. A coalition inspired in part by Churchill’s moral fire finally prevailed in 1945.

By then communism threatened, and Churchill once again issued warnings about a rising global threat. His weary nation voted him out of office not long after war’s end, once again unable to endure his fiery warnings, but he was returned to office several years later, just as he was beginning to succumb to the strain of age. He lived the last decade of his life as one of the most honored men in history.

He had helped lead England through two world wars, a global depression, and the threat of communist subversion. His oratorical gifts had defined the great battles of his age and lifted the British people to their best. He also modeled a brand of leadership that will be emulated for generations. He was, indeed, the greatest man in the world at the end of his life.

This is but a brief outline of Churchill’s life. I hope you will delve further into what he has to teach by reading his books as well as some of the brilliant volumes written about him. I’ve spent many hours at the great man’s feet through the benefits of literature, and they have proven among the most transforming hours I’ve ever known.

I could not help but be moved by how much Churchill suffered. To know his story is to know that the inspiration he offered to the world in time of crisis was fashioned first in his own dark nights of the soul. He battled depression all his days. One of his children committed suicide, one died in infancy, and two let alcohol ruin their lives. Churchill made some disastrous decisions while in public office, and many in English society never forgave him. These comprise a small portion of the many hardships he endured.

The darkest specter that hovered over his life, though, was his father’s near total disregard for him. It is hard to witness and even harder to explain, but it was one of the most defining forces in Churchill’s life. What he became, both the flawed man and the heroic statesman, was fashioned largely by the crushing force of his father’s hatred. We can pity Churchill for this agonizing experience, but we should also be grateful that in his battle to outstrip what could have been a deforming curse, he offers us vital lessons of true manhood.

It may help soften what we will be tempted to feel toward Winston’s father to know he had contracted a disease that progressively affected his mind. Nearly all of Churchill’s life, his father was slowly descending into madness. Knowing this might have helped a bit, but nothing can arm a boy against his own father’s spite and derision.

Nearly from the time Winston was born, his father thought him retarded. He rarely spoke to his son, had little hope for his prospects, and wounded him often with his mounting rage. Winston’s own son, Randolph, later wrote that “the neglect and lack of interest in him shown by his parents were remarkable, even judged by the standards of late Victorian and Edwardian days.”1 Randolph was speaking largely of his grandfather, who treated Winston with callous disregard.

As early as possible, Winston was shipped off to boarding school. His letters to his parents during this time rend the heart. He constantly pleaded for attention, spoke of how miserable he was, and begged for even a short visit from his parents. Nothing came of it. During this time it was not out of character for Lord Randolph to make a speech very near Winston’s school, yet never cross the street to visit his son. He had determined, the troubled man once mysteriously said, to maintain before Winston “a stony and acid silence.”2

What makes Lord Randolph’s attitude toward Winston particularly difficult to stomach is how adoring and openhearted the boy was. Churchill himself later recounted how proud he had been when his father visited his room one day and took stock of Winston’s vast collection of toy soldiers, all arrayed in battlefield formation. Randolph made a “formal visit of inspection” and “spent twenty minutes studying the scene—which was really impressive—with a keen eye and captivating smile. At the end he asked me if I would like to go into the Army. I thought it would be splendid to command an Army, so I said ‘Yes’ at once: and immediately I was taken at my word.” The memory ought to have been a happy one for Winston, but the thrill left when he was eventually told of his father’s motive: “For years I thought my father with his experience and flair had discerned in me the qualities of military genius. But I was told later that he had only come to the conclusion that I was not clever enough to go to the Bar.”3 Such wounds and disappointment haunted Churchill all of his life.

A more bruising episode occurred when a watch Winston’s father had given him fell into a stream near a deep pool at Sandhurst. Though he was twenty years old at the time, Winston was terrified of his father’s wrath. He instantly took off his clothes and plunged into the stream to look for the watch. Not finding it, he arranged to have the pool dredged. The watch still did not show itself. Winston decided to pay twenty-three soldiers to dig a new course for the stream and then he borrowed the school fire engine to pump the pool dry. Finally, he found the watch and sent it to a London watchmaker’s shop for repair.

Somehow, his father learned what had happened. His angry letter reveals the blowtorch of derision Winston often faced. Lord Randolph assured his son that his conduct was “shameful,” that he was a “young stupid” who was “not to be trusted,” and that his younger brother, Jack, was “vastly” his “superior.” It was an excessively harsh response to a fairly minor mistake. In later years, Winston would be able see his father’s mental imbalance in this episode. At the time he had no filter, and the words lacerated his soul. Even when Churchill was nearing the end of his life, he sometimes thought he could hear his father’s voice. Always it was scolding him for some misdeed. By then, Lord Randolph had been dead for half a century.

How did Churchill survive it? How did he overcome his father’s bludgeoning to lead an exceptional life? He might easily have lived as a bitter, damaged man. He might have fulfilled one of his father’s many curses—“you will become a mere social wastrel, one of the hundreds of public school failures, and you will degenerate into a shabby unhappy and futile existence”—and never served mankind as he did.4 How did he keep his wounds from determining the course of his life?

The truth is that Churchill simply made a choice. He might have given himself to snarling bitterness and regret. Instead, he decided to see himself as an extension of the good in his father’s life. He chose a pleasant continuity rather than a harsh antagonism.

We see this in his later account of his father’s death in 1895. A lesser man might have rejoiced that the tyrant was dead. Winston wrote, “All my dreams of comradeship with him, of entering Parliament at his side and in his support were ended. There remained for me only to pursue his aims and vindicate his memory.”5 Clearly he had decided to let his father’s vision propel him, to draw purpose rather than cancerous bitterness from his memories.

Winston also chose to weave this benevolent view of his harsh experience into a philosophy others could live by. Consider, for example, what these words have meant to those raised by fathers like Lord Randolph: “Solitary trees, if they grow at all, grow strong; and a boy deprived of a father’s care often develops, if he escapes the perils of youth, an independence and vigour of thought which may restore in after life the heavy loss of early days.”6

Consider also how many of Churchill’s admirers must have taken comfort in this conclusion: “Famous men are usually the product of an unhappy childhood. The stern compression of circumstances, the twinges of adversity, the spur of slights and taunts in early years, are needed to evoke that ruthless fixity of purpose and tenacious mother wit without which great actions are seldom accomplished.”7

Churchill managed to transform brutal treatment by a father into fuel for the great actions that marked his life. By doing so, he modeled a vital principle of manly living for us. This is to take nothing away from women, who sustain the same wounds men do—and often more of them. Yet women tend to handle pain and hardship better than most men do. They tend to be more realistic, less surprised by bruising experiences. This means they feel less personally betrayed by hurt and difficulty, so they are generally better able to let go of offense and move on in life. Men often seem perpetually stunned by the hard things that befall them. They can’t seem to stop nursing their wounds and recounting their grievances. They pick at their scars and in the process make their wounds worse.

I’m sorry to be so blunt, gentlemen, but my experience is that, generally speaking, if a man does not arrive at a meaning for his pains—and if that meaning does not evolve into a mandate for his future—then he is very likely to allow his sufferings to crush him. He’ll use them as an excuse for failure, a barrier against people, and a shield against his own emotions.

This is why Churchill’s example is so important. His father brutalized him emotionally. Some scholars go so far as to say that Lord Randolph hated Winston. Yet Winston allowed these harsh winds to lift him to greater heights. Like a skilled glider pilot positioning himself to rise on thermal winds, Winston chose to position himself internally so that he ended up benefiting from his father’s cruelty while he also lovingly extended his father’s legacy. He never denied the pain and the torment of what he had been through, but he simply chose not to make them the epitaph over his life.

Thank God he did. Look at his impact upon the course of world history. Look at what might have been lost had he succumbed to the imprint of a mentally imbalanced man upon his life.

The good news for us is that Churchill did not outstrip his father’s curses because he was an exceptional man. He became an exceptional man because he worked to outstrip his father’s curses. We can do the same. It is not out of our reach. It is, instead, one of the skills of living out the full meaning of manhood.