IF YOU ARE A HUNTER, YOU MAY ALREADY KNOW WHY SOME OF our founding fathers wanted the national symbol to be the turkey rather than the eagle. As beautiful as they are, eagles are scavengers. The founding fathers were men still taming a wilderness, and they knew this. They weren’t impressed. They were impressed with the turkey. If you have ever hunted turkeys, you were probably impressed too.

They are unbelievably fast creatures, capable of running twenty-five miles per hour and flying at speeds up to fifty-five miles per hour. They are also smart and constantly on the alert. Hunters like to say a deer thinks every hunter is a tree stump but a turkey thinks every tree stump is a hunter. They can be hard to find, harder to kill, and then, just to be ornery, turkeys make themselves hard to clean after they’re dead. There are as many as fifty-five hundred feathers on an adult turkey.

This is the wild turkey, though. The domesticated turkey is another story. They are idiots, perhaps the dumbest animals alive. Domesticated turkeys will eat themselves to death unless someone stops them. If thunder frightens them, they will often bunch up in one corner of their pen and suffocate each other.

Interesting, isn’t it? In the wild, turkeys are amazing. When domesticated, turkeys are so stupid they have to be kept from accidentally killing themselves a dozen different ways.

Gentlemen, let’s admit it: most of us are tragically overdomesticated. We have hardly any connection to the wild or our wilder selves. Words like adventure, exploit, and quest no longer apply to us. It is why we are soft, whiney, and bored.

Let’s let the words of some wise ones convict us.

Men of age object too much, consult too long, adventure too little, repent too soon, and seldom drive business home to the full period, but content themselves with a mediocrity of success.

—Francis Bacon, “Of Youth and Age, “from The Essays; Or Counsels, Civil and Moral

I think that sense of adventure gets tamed out of us. We also get frightened. Somewhere along the way, a man loses that confidence, that recklessness or fearlessness he had as a boy. Somewhere along the story of his life, doubt comes in. And a doubt goes like this: “No you don’t. You don’t have what it takes. You can’t come through. You can’t pull this off. So just put your nose to the horse in front of you and get in line and just become a gelding. Tie your reins up there at the corporate corral and give up any sense of risk.”

—John Eldredge, in 10 Passions of a Man’s Soul (2006)

Security is mostly a superstition. It does not exist in nature, nor do the children of men as a whole experience it. Avoiding danger is no safer in the long run than outright exposure. Life is either a daring adventure, or nothing.

—Helen Keller, from The Open Door (1957)

I read these words, and I know I’ve lost something. I’ve become a domesticated turkey. God help me. I’ve had the risk and the daring and the need for adventure squeezed out of me by duty and the ease of modern life. I don’t plan to stay this way.

My inner GPS needs resetting if I’m going to navigate the geography of manliness. Perhaps taking a good look at a man who mapped that geography more than a century ago will help me recover myself. Come along with me.

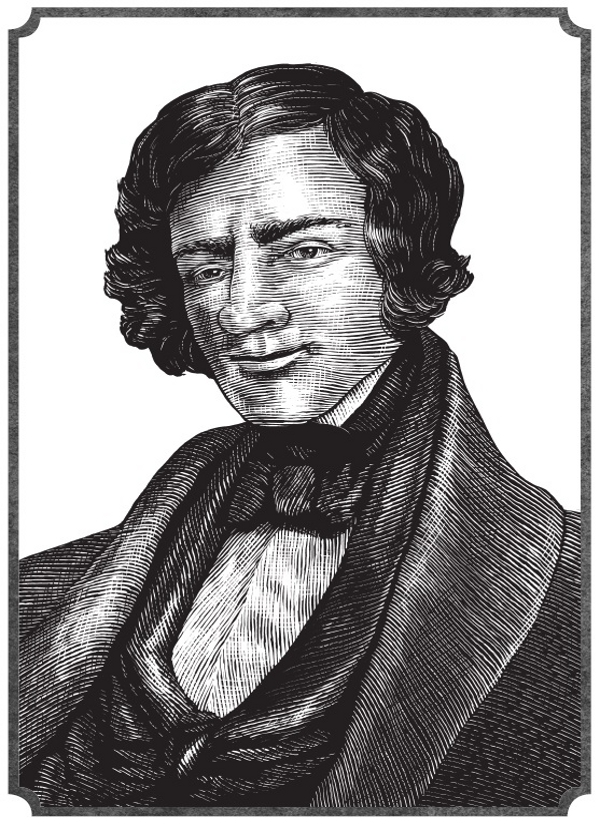

Let’s consider the life of Jedediah Smith, one of the greatest explorers and mountain men in American history. His list of firsts is stunning. He was the first white man to journey overland to the Great Salt Lake, the Colorado River, and the Mojave Desert. He was the first US citizen to explore the Sierra Nevada and the Great Basin in an eastward direction. He was the first American to journey through California to the Oregon Country. He also discovered the famous South Pass that pioneers used in droves to reach the Oregon region. His discoveries and explorations changed the westward expansion of the nation and thus the nation itself. In the process, he survived three massacres, some of the coldest weather on record, and mauling by a bear.

These achievements would be magnificent had he lived a hundred years, but he died at the age of thirty-two, having begun his journeys only a decade before.

Smith was born in Jericho, New York, on January 6, 1799. He came from two God-fearing New England families and had the good fortune to be mentored by a series of godly men. In his early years, two Methodist circuit riders taught him much of what they knew. Later, Dr. Titus G. V. Simons, a pioneer physician close to the Smith family, instilled in young “Diah” a love of nature and adventure. Simons gave his young friend a copy of Lewis and Clark’s 1814 chronicle of their epic journey to the Pacific Ocean. Smith read the classic, acquired a hunger for adventure from its pages, and kept it at his side for the rest of his life.

In 1822, twenty-three-year-old Smith stumbled upon an advertisement that changed his life. It was General William Ashley’s famous call for adventurous men.

TO

Enterprising Young Men

The subscriber wishes to engage ONE HUNDRED MEN, to ascend the river Missouri to its source, there to be employed for one, two or three years.—For particulars enquire of Major Andrew Henry, near the Lead Mines, in the County of Washington, (who will ascend with and command the party) or to the subscriber at St. Louis.

Wm. H. Ashley

The men who responded to this call became known as “Ashley’s Hundred.” Smith was one of them. He made several trips with Ashley up and down the Missouri River, often retracing the route Lewis and Clark had taken. Hardship and deadly skirmishes with natives tested him, but Smith knew he had discovered his life’s work. A year later, barely twenty-four years old, he was made captain of one of Ashley’s boat crews. His first assignment was to explore uncharted portions of the territory that would eventually become Montana.

Smith made many such trips during his short life. His great courage and yearning to see uncharted lands, along with the fearful difficulties he encountered, made him a legend even among legendary men.

For decades after he died, for example, men sat around campfires and told of the time he was stalked and attacked by a massive grizzly. The great beast tackled him, gashed open his side and took his head entirely in its jaws. Smith fought valiantly until the animal retreated at the sudden sound of approaching men. He was so mangled his men thought he was dead. His scalp had been torn jaggedly open, and his ear had been ripped from the side of his head. After his wounds were washed, Smith calmly instructed one of men in the proper method for sewing on his ear and closing his scalp. The scars this left added to the legend of the man, as did the long hair he grew to cover over his wounds.

On another occasion, as Smith led a party over the western mountains, winds blew so furiously that the side of one mountain was blown completely clean of snow, and the buffalo who usually grazed nearby stampeded to safer ground. Each night of this ordeal the men stayed awake to keep their blankets and heavy coats from blowing away. When they finally were able to light a fire, the wind blew the logs off the mountain. They endured these conditions for two days.

Realizing they had to descend, the party followed a creek downward into a canyon. There they huddled together for warmth. Frigid hours passed before they looked up at a ridge above them and saw a mountain sheep. The wind was still blowing so powerfully that, as the men watched from below, the animal was swept off of its ridge and slid down the face of a cliff before coming to a stop just at the feet of the hungry men. The stunned sheep was an easy kill. In Jedediah Smith and the Opening of the American West, Dale L. Morgan concluded his description of this episode with these words: “Clyman [one of Smith’s men] rose shivering from his blankets, made a fire and began to broil thin slices of meat. The savory odor aroused his companions, and the rest of the night they cooked, ate and told one another lies.”9

Such is the way of men. More important than these adventures to Smith was the power of his faith. He was descended from Massachusetts ancestors who knew and admired the Pilgrims of Plymouth. His people were fiercely Christian and bold. One of them, a pious man, was among the first to go over Niagara Falls and live to talk about it. Jedediah was of the same spirit. His men knew he always carried a Bible in his shirt pocket. They knew, also, that while they attacked a freshly cooked meal, Smith would first raise his voice in thanksgiving to God, which was both a genuine expression of gratitude and a rebuke to his crew for their pagan manners. He had memorized many lengthy passages of Scripture on his long, often solitary journeys and he routinely quoted verses aloud for miles on end as he traveled. His men may not have shared his faith, but they took comfort in their captain’s connection to God.

Jedediah Smith was an extraordinary man, but more important for us is that he was a man fully alive, devoted to adventure, and ever in search of the new and unexplored.

I’m being very open with you in this chapter. The Jedediah Smith part of me is in danger of dying early, just like the actual man. I have a pretty fantastic life. I travel. I speak. I work with powerful people. I appear on television. I have the wife of my dreams and children I love from the heart.

Is it enough? Yes, but this is not all there is to a man. Let’s be blunt. Men need to bark at the moon. Men need to blow something up. Men need to push themselves into a zone they don’t control—that in fact isn’t actually a zone.

Men need to go in pursuit. They need a quest.

This doesn’t happen much in my life. But it is going to. And you? Can you afford to lose this massive part of who you really are? I don’t think so. Nor do I think any of the men in our generation can afford to see this adventure-seeking part of themselves as dispensable.

I’m going to give the last word on this to a man I admire, who knows a thing or two about adventure. He’s Jon Krakauer, the author of Into the Wild, Into Thin Air, Under the Banner of Heaven, and Where Men Win Glory. Listen:

Make a radical change in your lifestyle and begin to boldly do things which you may previously never have thought of doing, or been too hesitant to attempt. So many people live within unhappy circumstances and yet will not take the initiative to change their situation because they are conditioned to a life of security, conformity, and conservation, all of which may appear to give one peace of mind, but in reality nothing is more damaging to the adventurous spirit within a man than a secure future. The very basic core of a man’s living spirit is his passion for adventure. The joy of life comes from our encounters with new experiences, and hence there is no greater joy than to have an endlessly changing horizon, for each day to have a new and different sun. If you want to get more out of life, you must lose your inclination for monotonous security and adopt a helter-skelter style of life that will at first appear to you to be crazy. But once you become accustomed to such a life you will see its full meaning and its incredible beauty.10

I don’t know what Jon Krakauer believes about spiritual things. I do know he believes the right things about a man’s need for adventure. I also know that God made me, he made me to live a fully engaged life; and to press against some frontier, push myself beyond my ease, and let my soul feel itself under threat. My first-class airplane seat, Hilton Hotel room, steak at Morton’s, iPad-addicted, way-overlauded life is not helping me be this kind of man.

Stay tuned. I’ll be back.