THE ENGLISH ESSAYIST WILLIAM HAZLITT WROTE IN LECTURES on the English Comic Writers (1819), “Man is the only animal that laughs and weeps: for he is the only animal that is struck by the difference between what things are and what they ought to be.” I think these words beautifully capture how men use humor, and they remind me of one of my favorite “great man” stories, a story that illustrates man humor at a critical moment in history.

It comes, as do so many other wonderful stories, from the life of Winston Churchill. During the years when England’s political left was systematically nationalizing the nation’s industries and services, Churchill walked out of a raucous session of Parliament to use the men’s room. This was in the days when the urinal was often a long metal or porcelain trough running the length of the room. While Churchill was relieving himself, one of the leading nationalizers entered the room and began doing his business right next to Churchill. The irritated conservative moved to the far end of the trough. “Feeling a bit stand off-ish today, Winston?” the new arrival asked mockingly.

“No,” growled Churchill. “But whenever you see anything big, you want to nationalize it.”

Now this, gentlemen, is perfect. It is a lesson in the art of manly humor. First, it is funny enough that you can’t wait to retell it. That’s important. Man humor has to have a sufficient laugh factor to qualify it for going viral. Second, it makes a point. In fact, it makes a very good point. Here, let me hide my privates so that your mindless socialism doesn’t mistake it for something the nation should own. Third, it draws blood. Man humor doesn’t always have to be the verbal equivalent of taking a swing at another man. Sometimes man humor is encouraging, or just entertaining and distracting. But when humor is needed to make an enemy feel pain, Churchill’s example is the way to go. Finally, it is slightly crude. Men like this. For a man to score a philosophical point by referring to a body part in such a way that his opponent can’t help but laugh too—now that is a Manly Moment of Victory.

Manly humor accomplishes many tasks, but most often it is like the ping of a submarine’s radar. Is there anyone out there? Am I safe being a true man with you?

Manly humor also explores the nature of things. Women reading this book might turn to their husbands and say, “Winston Churchill was crude!” But men know that Churchill was stating a broad truth about an important matter. You liberals are nationalizing everything you can in our society. But, listen up: it isn’t yours! It shouldn’t be nationalized just because it is big! And you’re probably just envious anyway!

Finally, in more serious situations, man humor confronts fear and prepares the heart for action. It’s a tool for dealing with danger, quieting panic, and calling comrades to prepare to charge. Call it gallows humor. Call it foxhole humor. Wherever it happens, it is how men use the sometimes crass but always funny comment to force a laugh and encourage their brothers-in-arms. Well, here we are, facing these monsters. At least we’re all together. And these idiots probably aren’t as fierce as we’ve been told. I hear they can’t find their manhood with a flashlight. Let’s take these fools!

Manly humor is one of the great joys of being a man. It is also one of the tools in the tool set of truly great men.

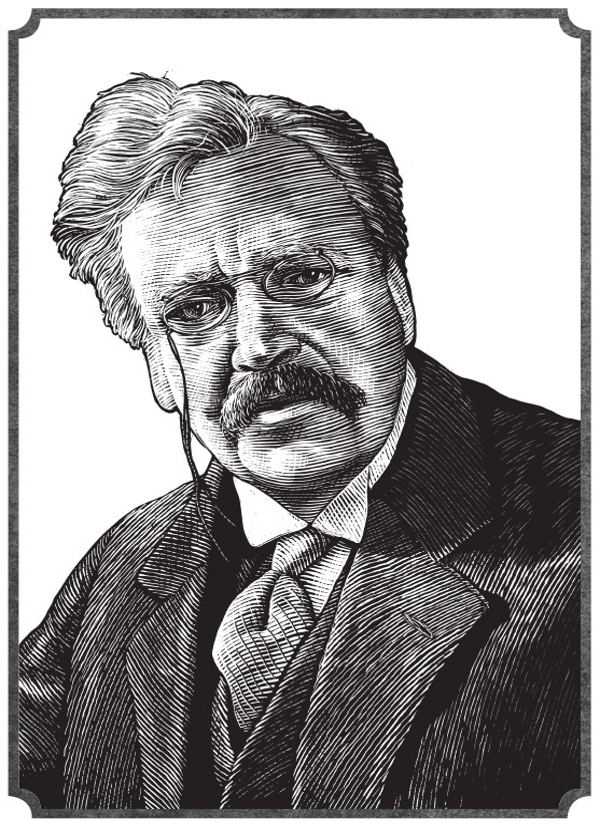

Comparable to Churchill in his use of humor was the English writer G. K. Chesterton, whose comedic style exhibited the kind of wonder and joy that arises from a Christian worldview. Though Chesterton is best known for his Father Brown detective novels, his biography of St. Thomas Aquinas, and his classic apologetic work Orthodoxy, he wrote much more, including eighty books, two hundred short stories, and four thousand articles. His writing was profoundly influential. Men as esteemed as Mahatma Gandhi, Bishop Fulton Sheen, and the Irish Republican leader Michael Collins acknowledged his influence upon them. Chesterton’s The Everlasting Man even played a critical role in C. S. Lewis’s conversion. He was certainly one of the great minds of the twentieth century.

Yet he was also, unquestionably, an oddball. He was physically gigantic—roughly six-foot-four and three hundred pounds—with a great mop of unkempt hair. He liked to joke that he had to be the most polite man in England because when he gave up his seat on a bus it meant that four women could sit in his place. He made a striking impression in his cape, crumpled hat, and walking stick, and seldom allowed much time to pass between cigars. He was also clumsy and astonishingly absentminded. He routinely sent telegrams to his wife to get help in finding his way. “Am at Aldersgate. Where am I supposed to be?” he would write. “Home,” she would often reply.

It may be that this disorientation to the real world was the price of his keen mind and sense of wonder. Chesterton saw the universe as filled with benevolent mystery. He believed a loving God designed creation to appeal to the curiosity and intellectual hunger of mankind. It is the reason he wrote articles about such seemingly trivial matters as chalk, lying in bed, and “what I found in my pocket.”

It is also the basis for his humor. When the younger sister of his fiancé was tragically killed, Chesterton insisted upon writing his love long letters of “rambling levity” during the worst of her grief. He told a friend, “I have sworn that Gertrude should not feel, wherever she is, that the comedy has gone out of our theater.”

He believed that no work of God should be untouched by levity, even death. When giving instructions to his wife about his funeral, he wrote, “If there occurs to anyone a really good joke about the look of my coffin, I command him by all the thunders to make it. If he doesn’t I’ll kick the lid up and make it myself . . . No, darling, if we are picking flowers we will not hide them if a hearse goes by.”11

His sense of wonder gave him a love of children, and he fabricated great schemes to involve them and enflame their imaginations. He once organized the Society for the Encouragement of Rain, which in England was not unlike creating an organization devoted to the preservation of snow in Alaska. Chesterton made membership cards and named his wife’s niece as President Rhoda Bastable and himself Secretary G. K. Chesterton. The bylaws of the organization required meetings to be held “on the Salisbury Plain where under the sign of an umbrella members were invited to partake of cakes and coffee in the rain.”12

Keep in mind that this man we see creating a fictional society with children was described by one scholar as “one of the deepest thinkers who ever existed.”13 A pope called him a gifted defender of the faith. Even one of his greatest opponents said that the world is not thankful enough for him. And his biographer, Dale Alquist, argued, “G. K. Chesterton was the best writer of the twentieth century. He said something about everything, and he said it better than anybody else.”14 Yet Chesterton dreamed of coffee on the Salisbury Plain with children—in the rain—and could not go to the store for milk without forgetting where he was meant to be because he was pondering the meaning of pocket lint.

He was a man of humor, fun, and fascination with the wonder of the universe and a great hunger to know. It made him exceptional, one of the giants of his age. Consider these witticisms, culled from his volumes of writing:15

“Art, like morality, consists of drawing the line somewhere.”

“By experts in poverty I do not mean sociologists, but poor men.”

“Once I planned to write a book of poems entirely about the things in my pocket. But I found it would be too long; and the age of the great epics is past.”

“Do not free the camel of the burden of his hump; you may be freeing him from being a camel.”

“Fallacies do not cease to be fallacies because they become fashions.”

“I believe in getting into hot water. I think it keeps you clean.”

“I’ve searched all the parks in all the cities and found no statues of committees.”

“Journalism consists largely in saying ‘Lord James is dead’ to people who never knew Lord James was alive.”

“Merely having an open mind is nothing; the object of opening the mind, as of opening the mouth, is to shut it again on something solid.”

“Moderate strength is shown in violence, supreme strength is shown in levity.”

“No man knows he is young while he is young.”

“One of the great disadvantages of hurry is that it takes such a long time.”

“People generally quarrel because they cannot argue.”

“The Christian ideal has not been tried and found wanting. It has been found difficult and left untried.”

“There is no man really clever who has not found that he is stupid.”

“The poor have sometimes objected to being governed badly; the rich have always objected to being governed at all.”

“The reformer is always right about what is wrong. He is generally wrong about what is right.”

“To be clever enough to get all the money, one must be stupid enough to want it.”

Laughing, joking, teasing, and storytelling are some of the best experiences in life. They enrich our days, bind us to others, teach us, and make life sweet and endurable. They are gifts from God and fruits of humility and wonder, since they are only possible when we see the flaws of the world but content ourselves with the knowledge that even flaws have purpose in the plan of God. We can relax then and laugh, crack the joke, or tell the funny story because we know our seriousness changes nothing. God rules, and we are free to delight in this fact and use humor to endure the way things are while we await the perfection that is coming.

Genuine men understand the power and meaning of humor. Some have greater gifts for joking and storytelling than others, but all can at least understand why humor is important, what it does for the soul of the fearful and hurting, and why it is so essential to what a man is made to do. Humor allows us to lighten the heart, encourage our children when they fail, ease stress from our wives, motivate younger men, and unify friends. Humor also allows us to drain the terror from our souls before battle.

It can also be a tool for seizing the moment for a greater good. No one was more skilled at this than Winston Churchill, and it would be fitting to end this chapter with a few of his more brilliant performances.

In the darkest days of World War II, Churchill lived with the Roosevelts at the White House during the many days required to determine strategies and negotiate matters like US aid for England. Many Americans in Congress and in the press charged that Churchill was being deceptive by asking for far more aid than England needed. Suspicions swirled in newspaper headlines. Tensions were thick even as Roosevelt and Churchill met.

One day Churchill emerged from his bath—he bathed every day, sometimes several times a day—just as an aide wheeled Roosevelt into Churchill’s room. Seeing the prime minister of England wrapped in a towel, the embarrassed Roosevelt ordered his aide to wheel him out so Churchill could have his privacy. Astutely, Churchill seized the moment for a larger cause. Holding up a detaining hand, he removed the towel and solemnly proclaimed, “The prime minister of Great Britain has nothing to hide from the president of the United States.” Churchill’s point was made, and history was changed because of it.

Finally, there were several women who irritated Churchill. Unfortunately, he found himself at dinners with each of them. One was Lady Astor, ever a thorn in his side. During their conversation one evening, Lady Astor grew so exasperated with Churchill that she exclaimed, “Winston, if I were your wife I’d poison your soup.” He replied without hesitation, “Nancy, if I were your husband, I’d drink it.” On another occasion, the second woman who bedeviled Churchill informed him that she liked neither his politics nor the new mustache he was sporting. He retorted, “Madam, I see no earthly reason why you should come into contact with either.”

Churchill wrote, “In my belief, you cannot deal with the most serious things in the world unless you also understand the most amusing.”16 He, like Chesterton, teaches us that humor is more than a form of play. It grows from our view of the world. It is a tool of manly leadership. It is a gracious gift from God as we live in a troubling world. Thank God for Chesterton and Churchill!