MY FATHER RARELY SPOKE ABOUT WHAT HE FELT OR BELIEVED. He was an army officer, which made him demanding about performance but almost entirely uninterested in why anyone performed. His message, even to his sons, was “believe what you want but perform as I tell you.”

In fact, he once said to me—probably to tweak my mother who was a devoted Christian—“I’ll tell you what you can believe. You can believe that if the yard isn’t mowed by three this afternoon, judgment day will descend. The last trumpet will sound for you!”

That was Dad.

I was surprised, then, when he offered a little insight into his soul between football games on a Saturday afternoon in 1977. I was home from college for the Christmas holidays and was “spending time” with Dad, which meant watching football from mid-morning to midnight.

When the second game of the day ended, and we were reprovisioning for the third, Dad rubbed his hands together eagerly, said something about how pitifully a certain quarterback had been playing, and then declared to the television in our kitchen, “But maybe it will be different today. I love to see a man improve upon himself.”

This may seem insignificant, but it was one of only four or five insights into Dad’s soul I was ever allowed. Like the others, this one came to me almost by accident. Dad wasn’t even talking to me when he said it. He was talking to his “best friend,” the anchor of CBS Sports.

I’ve never forgotten it and, in a way I can’t fully explain, Dad’s words left me with a fascination for people who fail and then strive to overcome it. I’ve studied them in history. I’ve tracked them in the headlines. In time, I even gained a reputation for counseling men who had known disaster but who were determined to rise again. Some of them rebuilt. Some did not. As each story unfolded, I thought of my father and his words: “I love to see a man improve upon himself.”

Through all of this, I began to understand that the simple willingness to fight back after misfortune is one of the most important features of genuine manliness. Women certainly face these crises, too, but frankly they seem to me more courageous and capable at such moments. Men seem more likely to doubt themselves, more likely to put a bullet through their heads or live the rest of their lives at the bottom of a bottle. The statistics bear this out. Losing all and reclaiming it again while friends keep a suspicious distance and the words of critics sear the soul—these seem to me about the hardest things a man can face, and it is not surprising that many men never recover themselves.

Rudyard Kipling said it well in his poem “If—,” in which he almost perfectly defined the manly virtues for all time. The stanzas about a man losing all and rebuilding again have always seemed to me a fleshing out of my father’s single sentence.

If you can bear to hear the truth you’ve spoken

Twisted by knaves to make a trap for fools,

Or watch the things you gave your life to, broken,

And stoop and build ’em up with worn-out tools:

If you can make one heap of all your winnings

And risk it on one turn of pitch-and-toss,

And lose, and start again at your beginnings

And never breathe a word about your loss . . .

You’ll be a Man, my son!

Now there are many examples of men who have known disgrace and then have ascended again. Churchill did. Lincoln did. So did MacArthur, Patton, Booker T. Washington, and Alfred the Great. Gandhi did also. As did King George VI of England. The list seems unending, and it can lead us to believe that greatness is not really possible without some early failure to overcome.

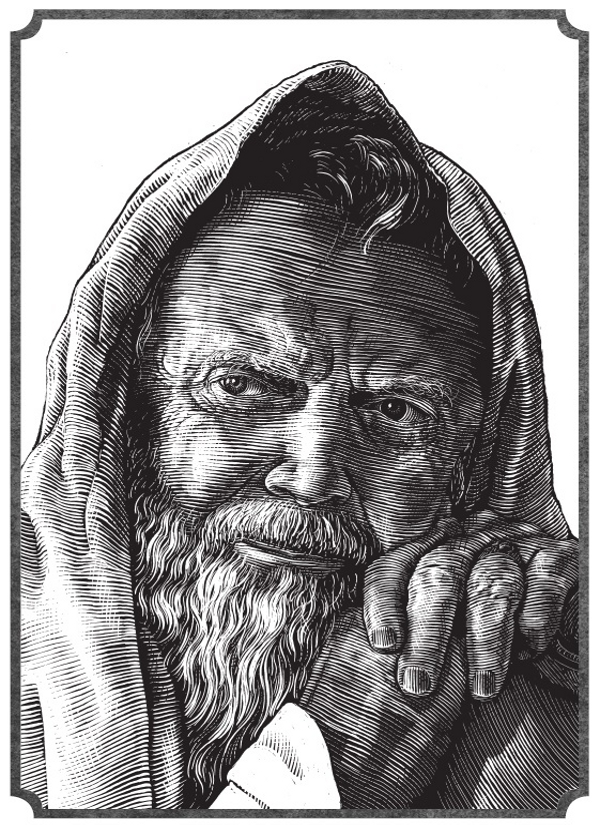

My favorite version of this kind of story will surprise you. It comes from the life of Mark the apostle. I love his tale because it is one of the most public in all of human history. It has to be—it’s in the Bible! I love it also because, though it is right there on the pages of Scripture, it is revealed only in bits and pieces. Most people miss it completely. Mark’s story also draws me because it is gritty, raw, and embarrassing. Nothing is kept from us, and I think this is a signal that we are supposed to take it all in and then live differently for having done so.

It is important for us to remember that Mark is among the greatest men in the history of Christianity. He is one of only four men who were privileged to write a gospel of Jesus Christ that ended up in the pages of the New Testament. He walked with giants like Peter and Paul. Early historians lauded him as a hero because of his gallant work in Egypt. He was also martyred, which gives him a holy and honored place in Christian memory. We should keep these later honors in mind as we ponder Mark’s early years, a time when he was certainly anything but a hero.

We meet Mark in the pages of the Bible with these words: “A young man, wearing nothing but a linen garment, was following Jesus. When they seized him, he fled naked, leaving his garment behind” (Mark 14:51–52 NIV). I can’t prove it definitely and scholars will debate it until the end of time, but I believe this young man is Mark. I believe these words are how Mark remembered this odd incident many decades after it occurred. He is thinking back upon the most terrifying, humiliating moment of his life. He wants us to see it just as it was.

We know a few things about Mark that help us understand this moment. He was from a wealthy family who owned a large home in Jerusalem. Jesus and his disciples often met there. In fact, the final Passover meal that Jesus ate with his disciples was likely eaten in an upper room of this home. As the early church gained its footing, believers met there regularly, and this is why, when Peter was released from King Herod’s prison around AD 44, he went directly to Mark’s house. He knew he would find fellow believers there (see Acts 12:12).

This might also explain why we meet Mark when he is wrapped only in a sheet and is fleeing soldiers. Since Jesus and his disciples likely ate the Last Supper at Mark’s house, soldiers might well have been sent there to arrest Jesus after Judas betrayed him. The sound of men banging on the door of the house probably awakened Mark that night. Some scholars believe that he jumped up, wrapped himself quickly in his bedding, and ran to the place he knew Jesus would be: the grove surrounding a little olive press at the base of the Mount of Olives. Gethsemane.

When Mark arrived, soldiers had already captured Jesus. Mark watched for a moment and then realized he was in danger. Soldiers had already recognized him and were just trying to take him in hand. Naturally, Mark ran. One soldier nearly grabbed him but ended up with a handful of sheets. Mark scurried off into the night completely naked. Of course, he would never forget these moments. He saw Jesus arrested. He abandoned the rabbi. He barely escaped capture by soldiers and had to make his way home naked. This was a joke to the Romans, a scandal to the Jews, and a lasting humiliation to Mark. He had been a coward that night, as had all of those who followed Jesus.

This is why Mark was the only author of a gospel to mention this unusual episode in later years. It may also have been memorable to him, though, because it was not the only time he ran away.

I said earlier that when Peter was released from prison, he went to Mark’s mother’s house—to “the house of Mary, the mother of John, also called Mark” as Luke describes it in Acts 12. The point is the house belonged to Mark’s mother. It doesn’t seem there was a man around—a husband or a father. He’s absent. Scholars think Mark’s father was either dead by this time or he had become offended with his wife’s faith and left. Either way, young Mark was without a father. This is important in light of what was about to take place.

It is also important to know that the Barnabas mentioned in the New Testament is Mark’s cousin. Originally Barnabas’s name was Joseph, but the disciples loved him so dearly they renamed him in the loving, sometimes intimate way that men do. They stopped calling him Joseph and instead gave him a name that meant “son of encouragement.” That’s the kind of man Barnabas was. Luke took pains to say that Barnabas was “a good man, full of the Holy Spirit and faith” (Acts 11:24 NIV).

This good man may have tried to be something of a surrogate father to Mark. While Barnabas was doing important things in the early days of the church—giving large sums of money, introducing the newly converted Paul to the Christian leaders in Jerusalem, and serving the church as a trusted emissary—Mark was often at his cousin’s side. It was a privilege. It was also an opportunity to mature.

Finally, an even greater opportunity came Mark’s way. The leaders at Antioch commissioned Paul and Barnabas to break new ground for the gospel in the pagan world. The two men decided to take Mark with them. What an opportunity this was! Mark was granted the honored position of assisting the most important emissaries of Christ in the world at the time. It was the privilege of a lifetime.

But watch: Paul and Barnabas set out immediately to fulfill their commission. We read of their departure in Acts 13:4. They made their way to the island of Cyprus and proclaimed the gospel there for a short while, perhaps as much as a few weeks. It went well at first, but then we read this in Acts 13:13: “Paul and his companions sailed to Perga in Pamphylia, where John [Mark] left them to return to Jerusalem” (NIV).

What? Why? What happened? Mark didn’t make it even eight verses!

Unfortunately, we don’t know why. Maybe Mark didn’t like carrying the luggage or making the Starbucks run. Maybe he missed his mommy. Or perhaps Paul was too demanding. Mark may have yearned for his air conditioning or his big-screen TV or time to chat with friends on Facebook. Who knows? Whatever happened, Mark abandoned Paul and Barnabas. Everyone knew it too.

Keep watching now: Paul and Barnabas finished their journey and returned to Antioch. Before long there was a big stir about the Gentiles who were becoming Christians. The big question was whether they had to become Jews first. Did they have to be circumcised and live under the conditions of the law before they could follow Jesus? All the church leaders met in Jerusalem to iron these things out. Paul and Barnabas testified about their ministry to the Gentiles at this meeting in order to help the apostles decide the matter. All ended well.

This is when Barnabas made his big mistake. He suggested to Paul that they should return to the churches they planted on their previous journey. Paul eagerly agreed. Then Barnabas suggested that they take Mark with them again.

Paul was a great man but he could also be impatient and harsh. He was no “son of encouragement.” When Barnabas suggested they take Mark, Paul erupted. Luke, the author of the book of Acts, tells us that Paul and Barnabas had a “sharp dispute.” This is code language. What it means is that the two men had a fight. They argued, it got loud, it went on for some time, and things were said.

Remember that Mark is Barnabas’s cousin. Remember that Paul doesn’t care. The little twerp had betrayed them right at the start of their last journey and Paul had no intention of trusting him again. Mark was an immature mama’s boy and a sissy. There was no place for a weakling in the important work Paul and Barnabas were called to do. That’s what Paul argued, anyway.

What happened? Paul and Barnabas parted company angrily. Barnabas took Mark and went back to his home in Crete. Paul chose a man named Silas to work with, and the two struck off in a different direction. Luke tells us that Paul was “commended by the brothers” (Acts 15:40 ESV). This is also code language. It means the church leaders backed Paul.

Here is the tragedy. Paul and Barnabas never worked together again. The Holy Spirit had specifically told the church at Antioch to commission the two men as a team. They made one journey together and then parted company forever. And it was all because of Mark. The devastation is hard to watch. Barnabas is never mentioned again in the New Testament except as a memory. The early church is distracted and divided over the matter. The Holy Spirit’s express purposes are never fulfilled, at least never fulfilled by Paul and Barnabas as a team. It was a full-scale crisis for the early Christians and, again, it was all because Mark was too spoiled and immature to do his duty. The churches all over the Roman Empire knew about his failure too. Once again, people said, Mark had run away.

There could hardly be a larger failure than this. This seemingly small matter of a self-centered, undisciplined man threatened to divide the early church, hinder the Holy Spirit, and limit the evangelistic reach of God’s people. People thanked God that Paul had known what to do when Barnabas couldn’t see past his family biases.

This is where it all might have ended: with Mark’s name a byword for spoiled brat and man of no spirit.

It did not end in this tragic state, though, and to know why, we have to let our minds run to Crete. We don’t know exactly what happened there, but we can fit a few pieces together. We can be fairly sure that Mark came to regret his foolishness. Barnabas, ever the encourager, would have mentored his young cousin. He trained Mark and helped him become more the man he was destined to be. Something significant began to happen in Mark’s life. He became useful, trustworthy. His character changed, his understanding deepened. He became more like Jesus and less like the pleasure-seeking pagan world.

We get some sense of how much Mark had changed when nearly fifteen years after the initial crisis the church at Colossae came across these words in one of Paul’s letters. “My fellow prisoner Aristarchus sends you his greetings, as does Mark, the cousin of Barnabas” (Colossians 4:10 NIV).

What? Mark is back? What’s happened? We don’t know exactly. What we do know is that Paul was writing from a prison in the city of Rome and Mark was with him. Mark had returned from Crete and, obviously, had reconciled with Paul. Just after this first mention of Mark, Paul wrote, “You have received instructions about him; if he comes to you, welcome him” (v. 10). Clearly, Paul wanted the believers who were offended with Mark to open their hearts to him again. This must have been encouraging to hear throughout the churches. The season of bitterness had passed.

It gets even better. Sometime after his return and after the churches embraced him again, Mark must have served with Peter, because in 1 Peter 5:13, Peter refers to Mark as his “son.” Scholars believe that Mark’s gospel gives evidence of Peter’s influence, which means the two men may have served the Lord together for years on end, with Mark absorbing Peter’s memories of what it was like to walk at Jesus’ side.

All of this is heartening to witness, but then comes the tender conclusion. Years later, Paul is once again in a Roman prison, though not in “his own rented house” as he was during his first imprisonment (see Acts 28:30 NIV). Instead, he is in a dank, filthy hole in the ground where the Romans held the worst of prisoners. From this hellhole, Paul wrote his final letter, his second to Timothy. We can hear the final tone in his words, and we sense that he is preparing the churches for his death. He was wise to do this. He was likely executed not too many months after he wrote it.

So in the last chapter of the last letter Paul would ever write, we read these words: “Get Mark and bring him with you, because he is helpful to me in my ministry” (2 Timothy 4:11 NIV).

How much these words mean! How they reveal the change in both men and the triumph of forgiveness and grace. And how much the words must have meant to Mark’s still-bruised soul.

The story has progressed a great distance from the days when Paul and Barnabas fought angrily over whether to forgive Mark and take him on their second journey. Now, after all these years, Paul finds Mark helpful. Paul has mellowed, but then, Mark is no longer the complaining, unstable man/child who left the apostles he was assigned to serve—and after only eight verses!

Even this is not the end, though. You see, Mark had failed and failed horribly, but then he did what true men do: he gave himself to the changes his failures called for. He submitted to mentoring by Barnabas, then he risked presenting himself to Paul. They then reconciled. Finally, he served faithfully at Peter’s side. Unlike that first humiliating journey, Mark became a teachable man, a man who would do whatever he had to in order to live down his shame and repair the damage done.

We learn from the pages of early church historians that Mark eventually became the bishop of Alexandria. We are told he led his people well. We know, too, that a fierce wave of persecution washed over the Alexandrian church and Mark was ultimately killed. There is a tradition that tells us people honored this great man by saying, “This time, he did not run away.”

I cannot think of a more moving story of failure and restoration than this one from the life of Mark. That it is from the pages of the Bible and that it challenges some of our assumptions about the ideal of the first-century church makes me love it even more.

Mark’s story is for both men and women, of course, but it touches me most as a window into some of what it means to be a man. Life in this fallen world is risky and dangerous. Losses will come. Failures will happen. Our journey will not be a constant, joyful, upward ascent.

Because of what a man is meant to be for his family, his society, and his God, he cannot allow failure and loss to destroy him. He should live knowing that such seasons are possible, and he should have a firm grasp on the truth that will help him rebuild.

First, he has to know he is destined. He can rise again from any depth of destruction because he knows his life is defined by something more powerful than his own sin or stupidity. It is powered by the purpose determined for him by his God.

Second, he has to acknowledge his folly. Call it repentance. Call it “hanging a lantern on your weaknesses.” Call it brokenness or humility. Whatever we call it, realizing we are not as we should be and that hiding this fact only deepens the devastation is one of the great principles of turning around a damaged life.

Third, submit to more capable men. We do not have all the resources we need even in the best of times. We certainly don’t have what we need in seasons of failure and embarrassment. We have to have mentors, coaches, trainers, and fathers. We need men who don’t fear us and are tough enough to press painful truths into our lives. We can’t rebuild without them.

Finally, we will have to face those we’ve damaged. We cannot run. Many of the men I have worked with during their potentially life-defining failures have had to fight the temptation to run from the ruin every single day. It is essential in reclaiming your lost territory that you stay in that territory—despite the mountains of rubble you’ve created—and yield to the processes of both God and man that are designed to help you reclaim and rebuild.

Mark is one of my heroes. He was a manly man. Sure, he was one of the great saints of the church, but before that he was a knucklehead who did great damage when the Christian faith was just starting to spread out into the world. He responded with humility and courage, though, and ended up changing the world.

Now that is what a man does.